Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease that is familial in 10% of cases. We have identified a missense mutation in the gene encoding fused in sarcoma (FUS) in a British kindred, linked to ALS6. In a survey of 197 familial ALS index cases, we identified two further missense mutations in eight families. Postmortem analysis of three cases with FUS mutations showed FUS-immunoreactive cytoplasmic inclusions and predominantly lower motor neuron degeneration. Cellular expression studies revealed aberrant localization of mutant FUS protein. FUS is involved in the regulation of transcription and RNA splicing and transport, and it has functional homology to another ALS gene, TARDBP, which suggests that a common mechanism may underlie motor neuron degeneration.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) causes progressive muscular weakness due to the degeneration of motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord. The average age at onset is 60 years, and annual incidence is 1 to 2 per 100,000. Death due to respiratory failure occurs on average 3 years after symptom onset (1). Autosomal dominant familial ALS (FALS) is clinically and pathologically indistinguishable from sporadic disease (SALS) and accounts for ~10% of cases (2). Three genes have been confidently linked to classical FALS: SOD1, encoding CuZn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) (ALS1 OMIM 105400) (3); ANG, encoding angiogenin (4-6); and TARDP, encoding TAR DNA binding protein TDP-43 (ALS10 OMIM 612069) (7). SOD1 mutations are detected in 20% of FALS and 5% of SALS cases (3, 8). Mice transgenic for mutant human SOD1 develop selective motor neuron degeneration due to a toxic gain of function (9) that is not cell autonomous (10) and is associated with multimeric detergent-resistant cytoplasmic mutant SOD1 aggregates (11). Ubiquitinated TDP-43 inclusions are detected in the perikaryon in the motor neurons of ~90% of ALS cases and in the cortical neurons of a subset of frontotemporal lobar dementia (FTLD) cases (12, 13). Fourteen missense TDP-43 mutations have now been associated with ALS, and all but one reside in the C-terminal domain (7, 14-16).

In addition, individual FALS kindreds have been linked to chromosomes 18q (ALS3, OMIM 606640) (17) and 20p (ALS7, OMIM 608031) (18), whereas multiple kindreds with ALS and FTLD have been linked to chromosomes 9q (FTD/ALS1 OMIM 105550) (19) and 9p (ALSFTD2, OMIM 611454) (20-22). We previously linked one large multigenerational British kindred (F1) to a 42-Mb region on chromosome 16 with a multipoint lod score (logarithm of the odds ratio for linkage) of 3.85 (ALS6 OMIM 608030) (23). As two more individuals developed ALS, we repeated the genome-wide scan using the 10K single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays. This confirmed linkage to chromosome 16 with a conserved haplotype containing more than 400 genes (fig. S1). Using a candidate gene approach, we sequenced 279 exons from 32 genes and expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and 10 noncoding RNAs (tables S1 and S2). After our detection of mutations in TARDBP, we prioritized six genes containing similar domains within the linked region. A single base-pair change was identified in exon 15 of FUS (also known as translocation in liposarcoma or TLS) in the proband from the F1 kindred (fig. S2A). This change is predicted to result in an arginine to cysteine substitution at position 521 (R521C), which is in a highly conserved region at the very C terminus of the protein (fig. S2, B and C). The 1561 C>T (R521C) mutation was present in the DNA of all six affected members of F1 and cosegregated with the linked haplotype (Fig. 1A).

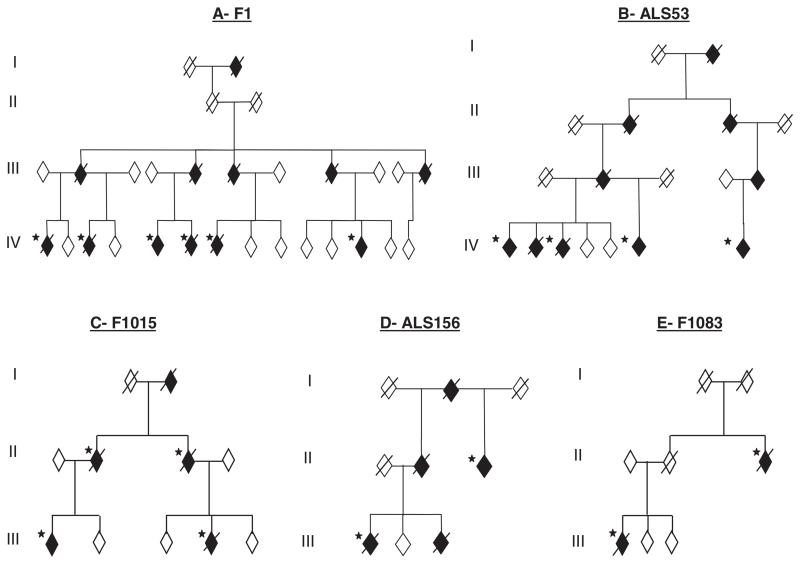

Fig. 1.

FUS mutations segregate with disease in five dominant ALS kindreds. Affected individuals are indicated by black symbols and unaffected individuals by open symbols. Slashed symbols indicate deceased individuals. Asterisks indicates an affected individual for whom DNA was available. All affected individuals tested carried their families’ mutation. Gender, birth order, and the mutation status of unaffected individuals have been omitted for reasons of confidentiality.

To determine the frequency of FUS mutations in FALS, we screened 197 index FALS cases in which SOD1, VAPB, ANG, Dynactin, CHMP2B, and TARDBP mutations had been excluded. We identified the same R521C mutation in a further four families, including three affected individuals from one kindred (ALS53) (Fig. 1B) and three more index FALS cases. In addition, we found a different base-pair change that is predicted to result in an arginine to histidine substitution, also at position 521 (1562 G>A, R521H) (fig. S2, A to C). The R521H mutation was identified in two families where it segregates with disease (F1015 and ALS156) (Fig. 1, C and D) and one index case. A third mutation was identified in exon 14 that is predicted to result in an arginine to glycine substitution at position 514 (1540 A>G, R514G) (fig. S2, A to C). This was detected in two affected members of the pedigree F1083 (Fig. 1E). No mutations were detected in exons 1 to 13 in the other FALS cases. Exons 14 and 15 of FUS were sequenced in 400 age, sex, and ethnically matched controls, and no mutations were detected. The frequency of FUS mutations in British and Australian SOD1-negative cases is ~4% (equivalent to 3% of all FALS cases).

Sufficient information to define a clinical phenotype was available in 20 individuals with FUS mutations. There was an even gender distribution (9 male, 11 female), the average age at onset was 44.5 years (n = 20), and average survival was 33 months (n = 18). The site of onset was cervical (10), lumbar (5), and bulbar (3). No affected individual developed cognitive deficits. Three cases with the FUSR521C and FUSR521H mutations underwent detailed neuropathological examination. All revealed severe lower motor neuron loss in the spinal cord (Fig. 2O) and to a lesser degree in the brain stem, whereas dorsal horn neurons appeared unaffected. There was evidence of mild myelin loss in the dorsal columns, but only one case had major pallor of the corticospinal tracts. There was mild to moderate upper motor neuron loss in the motor cortex. Ubiquitin and p62-immunopositive skeinlike cytoplasmic inclusions in anterior horn motor neurons of the spinal cord, which are hallmarks of classical ALS, were very rare, and TDP-43–positive inclusions within the cytoplasm and nucleus of neurons and glial cells were absent. Antibody to FUS labeled large globular and elongated cytoplasmic inclusions in spinal cord motor neurons and dystrophic neurites in all three ALS cases with FUS mutations (Fig. 2, A to F, and O). These were absent in normal control individuals (Fig. 2, G, H, and M), SOD1 mutant ALS cases (Fig. 2, I and J), and sporadic ALS cases (Fig. 2, K, L, and N).

Fig. 2.

Patients with FUS mutations develop cytoplasmic FUS immunoreactive inclusions in lower motor neurons. Antibody to FUS immunolabels inclusions within the anterior horn (dotted line) of the spinal cord in patients with FUS mutations (A to F and arrowheads in O). Staining in controls (G, H, and M), mutant SOD1 FALS (I and J), and SALS (K, L, and N) demonstrate diffuse nuclear staining (arrows) with variable intensity without inclusions. Scale bars, 12 μm [(A) to (L)], 50 μm [(M) to (O)].

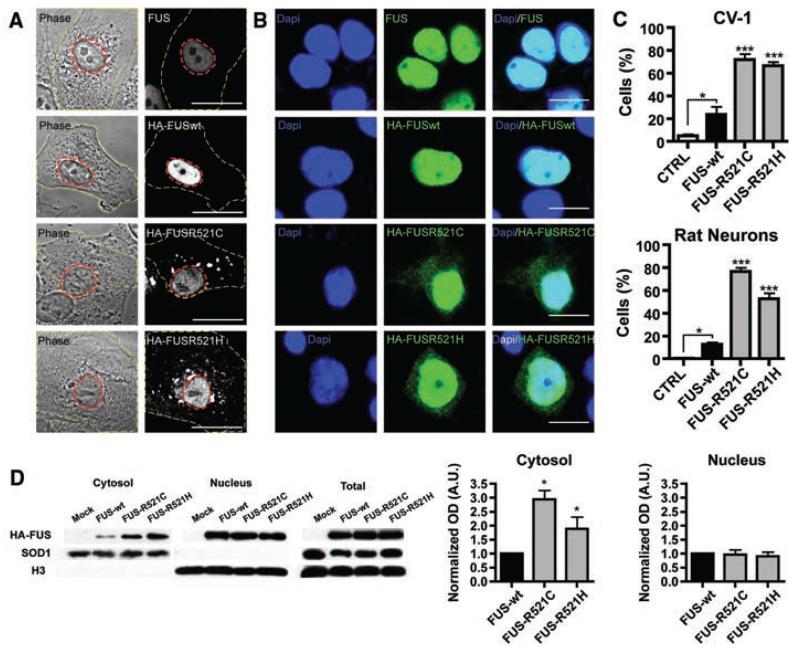

To assess the functional importance of these mutations, we transiently expressed N-terminally hemagglutinin(HA)–tagged wild-type FUS(FUSWT) and two mutants, (FUSR521C and FUSR521H) in CV-1 and N2A cell lines and rat cortical neurons. Staining for endogenous FUS in nontransfected cells indicated that the protein is predominantly localized to the nucleus. Transfected cells show an increase in cytoplasmic localization of the FUSR521C and FUSR521H protein when compared to the wild type, both with immunofluorscent labeling and by immunoblot (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

FUS mutations cause subcellular mislocalization. (A and B) The subcellular localization of endogenous FUS, transfected wild-type (HA-FUSWT), and FUS mutants (HA-FUSR521C, HA-FUSR521H) was determined in CV-1 cells (A) and rat cortical neurons (B) by immunofluorescence. The plasma membrane (A, yellow dash) and nucleus (A, red dash) of representative CV-1 cells are outlined on phase contrast (A, left panel) and corresponding FUS immunofluorescence images (A, right panel). Nuclear diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (B, left panel), FUS immunofluorescence (B, middle panel), and overlay (B, right panel) of representative cortical neurons are shown. Scale bars, 25 μm (A), 10 μm (B). (C) The percentage of CV-1 cells (upper panel) and cortical neurons (lower panel) showing FUS staining in the cytoplasm was significantly increased for mutant forms of FUS compared to wild-type and endogenous. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (P < 0.0001 for CV1 and neurons) followed by Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test (*, P < 0.05; ***, P <0.001). (D) FUS mutants show a significant increase in the cytosolic fraction. N2A cells transfected with FUSWT, FUSR521C, and FUSR521H were separated into cytosolic and nuclear fractions, and the amount of transfected FUS was determined by densitometry of antibody to HA immunoblots (mean ± SEM, n = 3). The purity of fractions was determined with antibody to SOD1 (cytosol) and antibody to histone H3 (nucleus), and the transfection efficiencies were compared in total cell lysates. Statistical significance was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test (*, P < 0.05).

FUS is a ubiquitously expressed, predominantly nuclear, protein that is involved in DNA repair and the regulation of transcription, RNA splicing, and export to the cytoplasm. The N terminus has a transcriptional activation domain which, after chromosomal translocation, produces fusion proteins that can cause Ewing’s sarcoma and acute myeloid leukemia (24). The C terminus contains RNA recognition motif (RRM), Arg-Gly-Gly (RGG) repeat rich, and zinc finger domains involved in RNA processing. FUS binds to the motor proteins kinesin (KIF5) (25) and myosin-Va (26) and is involved in mRNA transport; it is notable that defects in axonal transport are a pathological feature of ALS (27).

Mutations in the C-terminal domain of TDP-43 have been linked to ALS (7, 14-16) and are associated with mislocalization and inclusion formation, providing an almost exact parallel with FUS mutations. In the case of TDP-43 proteinopathies, it is not clear whether disease is due to a toxic gain, or loss, of function. Although toxicity might be a consequence of misfolded proteins overwhelming the protein surveillance machinery, the loss of TDP-43 from the nucleus in neurons with inclusions provides circumstantial evidence that nuclear RNA processing may be impaired. Equally, the presence of cytoplasmic aggregates might lead to the sequestration of proteins and/or RNAs in the cytoplasm, causing selective toxicity to cortical and motor neurons. The absence of TDP-43 inclusions in mutant FUS ALS cases implies that the FUS disease pathway is independent of TDP-43 aggregation. An exploration of how these two functionally related proteins cause neurodegeneration should provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying ALS pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This publication is dedicated to the patients and families who have contributed to this project and to B. Coote and C. Cecere for blood sample collection. Postmortem tissues were provided by MRC Neurodegenerative Diseases Brain Bank. This work was supported in the United Kingdom by grants from the American ALS Association, the Middlemass family, Lady Edith Wolfson Trust, Motor Neurone Disease Association UK, The Wellcome Trust, European Union (APOPIS consortium, contract LSHM-CT-2003-503330, and NeuroNE Consortium), National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health, The South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust, Medical Research Council UK, a Jack Cigman grant from King’s College Hospital Charity, The Heaton-Ellis Trust, and The Psychiatry Research Trust of the Institute of Psychiatry. In Australia the work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (CDA 511941) and a Peter Stearne grant from the Motor Neuron Disease Research Institute of Australia.

Footnotes

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/323/5918/1208/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 and S2

Tables S1 to S4

References

References and Notes

- 1.Shaw CE, al-Chalabi A, Leigh N. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2001;1:69. doi: 10.1007/s11910-001-0078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw CE, et al. Neurology. 1997;49:1612. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.6.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen DR. Nature. 1993;364:362. doi: 10.1038/364362c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conforti FL, et al. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2008;18:68. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenway MJ, et al. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:411. doi: 10.1038/ng1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paubel A, et al. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:1333. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.10.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sreedharan J, et al. Science. 2008;319:1668. doi: 10.1126/science.1154584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw CE, et al. Ann. Neurol. 1998;43:390. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY. Science. 1994;264:1772. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boillee S, et al. Science. 2006;312:1389. doi: 10.1126/science.1123511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Xu G, Borchelt DR. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;9:139. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackenzie IR, et al. Ann. Neurol. 2007;61:427. doi: 10.1002/ana.21147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann M, et al. Science. 2006;314:130. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gitcho MA, et al. Ann. Neurol. 2008;63:535. doi: 10.1002/ana.21344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabashi E, et al. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:572. doi: 10.1038/ng.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Deerlin VM, et al. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:409. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70071-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hand CK, et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;70:251. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sapp PC, et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:397. doi: 10.1086/377158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosler BA, et al. JAMA. 2000;284:1664. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morita M, et al. Neurology. 2006;66:839. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000200048.53766.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valdmanis PN, et al. Arch. Neurol. 2007;64:240. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vance C, et al. Brain. 2006;129:868. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruddy DM, et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:390. doi: 10.1086/377157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Law WJ, Cann KL, Hicks GG. Brief. Funct. Genomics Proteomics. 2006;5:8. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/ell015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanai Y, Dohmae N, Hirokawa N. Neuron. 2004;43:513. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshimura A, et al. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:2345. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Vos KJ, Grierson AJ, Ackerley S, Miller CC. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;31:151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.