Abstract

p-Nitrophenol (4-NP) is recognized as an environmental contaminant; it is used primarily for manufacturing medicines and pesticides. To date, several 4-NP-degrading bacteria have been isolated; however, the genetic information remains very limited. In this study, a novel 4-NP degradation gene cluster from a gram-positive bacterium, Rhodococcus opacus SAO101, was identified and characterized. The deduced amino acid sequences of npcB, npcA, and npcC showed identity with phenol 2-hydroxylase component B (reductase, PheA2) of Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius A7 (32%), with 2,4,6-trichlorophenol monooxygenase (TcpA) of Ralstonia eutropha JMP134 (44%), and with hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase (ORF2) of Arthrobacter sp. strain BA-5-17 (76%), respectively. The npcB, npcA, and npcC genes were cloned into pET-17b to construct the respective expression vectors pETnpcB, pETnpcA, and pETnpcC. Conversion of 4-NP was observed when a mixture of crude cell extracts of Escherichia coli containing pETnpcB and pETnpcA was used in the experiment. The mixture converted 4-NP to hydroxyquinol and also converted 4-nitrocatechol (4-NCA) to hydroxyquinol. Furthermore, the crude cell extract of E. coli containing pETnpcC converted hydroxyquinol to maleylacetate. These results suggested that npcB and npcA encode the two-component 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase and that npcC encodes hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase. The npcA and npcC mutant strains, SDA1 and SDC1, completely lost the ability to grow on 4-NP as the sole carbon source. These results clearly indicated that the cloned npc genes play an essential role in 4-NP mineralization in R. opacus SAO101.

Nitroaromatic compounds have been used in a number of ways, including in medicines, explosives, and pesticides (17, 32). Wide use of these nitroaromatic compounds and their subsequent release leads to environmental pollution. Due to this potential toxicity and persistence in the environment, rapid removal and detoxification of these compounds are necessary. p-Nitrophenol (4-NP) is among such compounds found in many different environments. This compound is used on a large scale in the synthesis of the aspirin substitute acetaminophen and in the manufacture of pesticides such as parathion and methylparathion (25, 32). In the environment, such pesticides are hydrolyzed and transformed to 4-NP; these pesticides have been considered to be the main source of 4-NP that has been detected in the environment (18, 19, 23). The toxicology and carcinogenicity of 4-NP have been studied and reviewed by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (1).

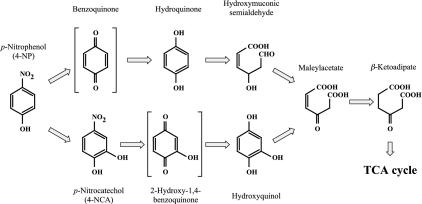

Several 4-NP-degrading bacteria have been isolated, and their degradation pathways have been studied. As shown in Fig. 1, the two major initial degradation pathways of 4-NP have been characterized. The degradation pathway in which 4-NP is converted to maleylacetate via hydroquinone (hydroquinone pathway) (Fig. 1, top) was preferentially found in gram-negative bacteria such as Burkholderia spp. and Moraxella spp. (21, 25). The degradation pathway in which 4-NP is converted via 4-nitrocathechol (4-NCA) and hydroxyquinol (hydroxyquinol pathway) (Fig. 1, bottom), was preferentially found in gram-positive bacteria such as Bacillus spp. and Arthrobacter spp. (10, 11). Although many studies of 4-NP degradation have been reported, genetic information related to 4-NP degradation remains limited. In association with the hydroquinone pathway, the 4-NP degradation genes were cloned from Pseudomonas sp. strain ENV2030 and Pseudomonas putida JS444 (32). In the case of the hydroxyquinol pathway, no 4-NP catabolic gene has been reported. The only nucleotide sequence of 4-NP degradation genes (nphA1A2) thus far reported was from Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1. The gene products NphA1 and NphA2 are reported to convert 4-NP to 4-NCA, but the genes involved in the further degradation of 4-NCA and its metabolites from strain PN1 have not been reported to date (26). Therefore, more information about the catabolic genes involved in 4-NP metabolism is still needed, and in particular, information about those genes that act on the hydroxyquinol pathway is considered to be highly desirable.

FIG. 1.

Proposed degradation pathway for 4-NP (11, 25, 32). TCA, trichloroacetic acid.

A gram-positive 4-NP degrader, Rhodococcus opacus SAO101, was originally isolated as a bacterium able to degrade dibenzo-p-dioxin (12). This strain also degrades biphenyl, naphthalene, phenol, benzene, dibenzofuran, dibenzo-p-dioxin, and 4-NP. In this study, a novel 4-NP catabolic gene cluster that acts on the hydroxyquinol pathway from strain SAO101 was isolated and characterized. First, we cloned the 4-NP degradation genes with the aid of PCR and by screening a genomic library. Second, the enzyme activities expressed in Escherichia coli were examined. We then isolated mutants with insertionally inactivated 4-NP catabolic genes and analyzed the mutants to address the functional importance of the 4-NP genes in strain SAO101. This is the first report of 4-NP degradation genes that are responsible for converting 4-NP to maleylacetate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The plasmids and bacterial strains used are listed in Table 1. Strain SAO101 was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and minimal salt medium (MM) with 4-NP or 4-NCA at 30°C (12). A resting-cell assay of Rhodococcus strains was also performed in MM supplemented with 500 μM substrate at 30°C. In addition, E. coli strains were grown in LB medium at 30 or 37°C; 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 40 μg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-Gal) per ml, 100 μg of ampicillin per ml, 50 μg of kanamycin per ml, and 30 μg of chloramphenicol per ml were added to the medium when needed.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Reference or origin |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| R. opacus | ||

| SAO101 | 4-NP degrader, wild type, 4-NP+ | 12 |

| SDC1 | npcC gene-disrupted mutant of SAO101, 4-NP− (Kmr) | This study |

| SDA1 | npcA gene-disrupted mutant of SAO101, 4-NP− (Kmr) | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 (rK− mK+) e14− (mcrA) supE44 relA1 Δ(lac-proAB)/F′[traD36 proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15] | Takara Shuzo |

| Rosetta(DE3)pLysS | F−ompT hsdSβ (rB− mB−) gal dcm, lacY1 (DE3) pLysSRARE (Cmr) | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescriptII KS, SK | Cloning vector, Apr | Stratagene |

| pBS-aphII | Cloning vector, Apr Kmr | This study |

| pHQ157 | Strain SAO101 cosmid library clone containing npc genes, Apr | This study |

| pET17b | Expression vector, Apr | Novagen |

| pETnpcBA | pET17b derivative carrying the npcBA genes | This study |

| pETnpcB | pET17b derivative carrying the npcB gene | This study |

| pETnpcA | pET17b derivative carrying the npcA gene | This study |

| pETnpcC | pET17b derivative carrying the npcC gene | This study |

4-NP+, growth on 4-NP; 4-NP−, no growth on 4-NP; Apr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance.

DNA manipulations and analysis.

Standard DNA techniques were performed basically as described elsewhere (13, 14, 24). Nucleotide sequence analyses were performed with a CEQ2000 DNA analysis system (Beckman Coulter). For the sequence analyses, GeneWorks (Intelligenetics, Mountain View, CA) and GENETYX (Software Development, Tokyo, Japan), as well as the online BLAST homology search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and ClustalW multiple-sequence alignment (http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) software packages were used.

RT-PCR analyses.

The total RNA of strain SAO101 cells grown in LB medium or 4-NP-supplemented MM were extracted with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analyses were performed with the ReverTra Ace-α kit (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Five primer sets were used for RT-PCR. Primer set A (forward, 5′-TCGGACACTTCGCAAGTGG-3′; reverse, 5′-CGGTAGTACGACAGTGGATTGC-3′) amplified the internal 409 bp of npcB. Primer set B (forward, 5′-CGCCTACCACGAATTCTGG-3′; reverse, 5′-ATTGCCGATGTGCTGAACG-3′) amplified the internal 583 bp of npcA. Primer set C (forward, 5′-CAGGAGTTCATCCTGCTCTCC-3′; reverse, 5′-CACGAAGTCCTTGATCAGCG-3′) amplified the internal 567 bp of npcC. Primer set D (forward, 5′-GCAATCCACTGTCGTACTACCG-3′; reverse, 5′-CCAGAATTCGTGGTAGGCG-3′) amplified 388 bp of the npcB-npcA spanning region. Primer set E (forward, 5′-TTCAGCACATCGGCAATCC-3′; reverse, 5′-GAGAGCAGGATGAACTCCTGG-3′) amplified 1,112 bp of the npcA-npcC spanning region.

Construction of high-expression vectors of npc genes.

Each npc gene was PCR amplified and ligated to an expression vector, pET17b (Novagen). All of these genes were amplified with a forward primer designed to contain the NdeI restriction site at its own ATG start codon in order to achieve ligation at the NdeI ATG site of the expression vector. The resultant plasmids pETnpcBA, pETnpcB, pETnpcA, and pETnpcC contained npcBA, npcB, npcA, and npcC, respectively. All four expression plasmids were introduced into the expression host strain E. coli Rosetta(DE3)pLysS (Novagen).

Crude cell extract enzyme assay.

The crude cell extract enzyme assay was performed basically like the 2,4,6-trichlorophenol (2,4,6-TCP) catabolic enzyme assay previously reported by Hatta et al. and Takizawa et al. (9, 27). NpcBA was demonstrated by detecting the depletion of the substrate. To detect NpcB and NpcA (4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase) enzyme activity, the cell extracts were diluted with the same volume of modified GPME buffer (27), and final concentrations of 200 μM substrate, 5 μM flavin adenine dinuleotide, and 2 mM NADH were added to the reaction mixture, which was then incubated at 30°C with gentle shaking. A 0.1-ml aliquot of the reaction mixture was removed at appropriate times and subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses. To detect the NpcC enzyme (hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase), enzymatic activity was measured in 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 200 μM hydroxyquinol, 0.5 mM FeSO4, and 5% (vol/vol) cell extract at 30°C with gentle shaking. A 0.1-ml aliquot was withdrawn and analyzed as described above. Protein concentrations were determined with a Bio-Rad Laboratories protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Analytical methods. (i) HPLC analysis.

Each 0.1-ml sample from the crude cell extract enzyme assay was mixed with an equal volume of methanol immediately after sampling. The samples were then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatants were subjected to HPLC analysis. HPLC analysis was carried out at room temperature with an Alliance 2690 system (Waters, Milford, Mass.) equipped with a μBondasphere column (3.9 [inner diameter] by 150 mm; Waters). The mobile phase was a mixture of water (69.93%), acetonitrile (30.0%), and acetate (0.07%), and the flow rate was 2.0 ml/min. In this analysis, 4-NP and 4-NCA were detected at 320 nm and hydroxyquinol was detected at 254 nm, using a UV spectrophotometric detector.

(ii) GC-MS analysis.

Each 0.1-ml sample from the crude cell extract enzyme assay and from the resting-cell assay was mixed with 5 μl of concentrated HCl, and each sample was saturated with NaCl; 0.2 ml of ethyl acetate was then added and mixed vigorously for 5 min. The samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min, and the upper ethyl acetate phase was recovered. Samples extracted with ethyl acetate were evaporated and treated with an N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl) acetamide kit (B0911; Tokyo Kasei, Tokyo, Japan) to generate a trimethylsilyl derivative. GC-MS analysis was performed on a GC-17A, QP5050 GC-MS system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a DB-5 capillary column (30 m by 0.25 mm) (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, Calif.). Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. The oven parameters were 50°C for 2 min and then a 30°C/min increase to a final temperature of 250°C for 3 min.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence determined in this study has been deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank databases under accession no. AB154422.

RESULTS

PCR cloning of the hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase gene.

To obtain 4-NP degradation genes, we first attempted to isolate the hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase gene, whose gene product (enzyme) converts hydroxyquinol to maleylacetate. This gene is presumed to be involved in the 4-NP degradation pathway (Fig. 1). Three published hydroxyquinol dioxygenase gene sequences, i.e., hadC of Burkholderia pickettii (9), tftH of Burkholderia cepacia AC1100 (5), and dxnF of Sphingomonas wittichi RW1 (2), were aligned, and a primer set was designed. With this primer set and the total DNA of strain SAO101 as a template, PCR was carried out. A DNA fragment of approximately 620 bp was amplified, and its nucleotide sequence showed similarity with those of some known hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase genes. Therefore, we used it in further experiments.

Isolation of 4-NP degradation genes.

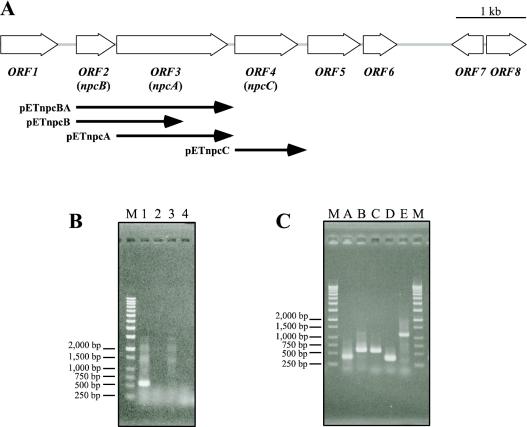

To obtain the flanking regions of the PCR-cloned gene, colony hybridization against E. coli cells containing a strain SAO101 cosmid gene library was performed with the PCR-cloned gene probe. A total of 1,000 E. coli colonies were screened, and four clones gave a positive hybridization signal. Among the positive clones, a cosmid designated pHQ157 was extracted, and the flanking nucleotide sequences of the PCR-cloned gene in pHQ157 were analyzed by the gene walking method. A 7.5-kb nucleotide sequence was determined, and seven open reading frames (ORFs) (ORF1 to -7) and one incomplete ORF (ORF8) were found in the sequenced region (Fig. 2A). The deduced amino acid sequences for the ORFs were used for a BLAST homology search (Table 2). The ORF1 product showed 33% identity with NodD (a LysR-type transcriptional regulator for nod genes) of Rhizobium sp. strain HW17b (28). The ORF2 and ORF3 products showed 32 and 44% identity with PheA2 (phenol 2-hydroxylase component B [reductase component]) of Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius A7 (7) and TcpA (2,4,6-TCP monooxygenase) of Ralstonia eutropha JMP134 (16), respectively. Moreover, the ORF3 product showed 42% identity with HadA (2,4,6-TCP monooxygenase) of Ralstonia pickettii DTP0602 (27). These two ORFs (ORF2 and ORF3) appeared to encode a reductase component and an oxygenase component, respectively, of a monooxygenase system. ORF4, which contained the complete sequence of the gene fragment cloned by PCR, seemed to encode a hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase. This ORF showed the highest identity (76%) with ORF2 (hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase) of Arthrobacter sp. strain BA-5-17 (20) and also showed 43 to 52% identity with hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenases from gram-negative bacteria, such as HadC of R. pickettii DTP0602 (9) and TcpC of R. eutropha JMP134 (16). Of the other ORFs found in the sequenced region, the products of ORF5 to -8 showed similarity with a putative secreted protein, a putative YjeB/Rrf2-type transcriptional regulator, a putative SoxR/MerR-type transcriptional regulator, and a putative drug transporter, respectively. Structural similarities between the ORF3 product and two known monooxygenase systems, TcpA and HadA 2,4,6-TCP monooxygenase, were observed. Therefore, ORF2 and ORF3 appeared to encode an oxygenase system especially for phenolic compounds. In addition, the ORF4 product is known to share similarities with TcpC and HadC hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase of 2,4,6-TCP degradation pathways. Therefore, based on these sequence similarities as well as the analogy between the 2,4,6-TCP degradation pathways (9, 16) and the proposed 4-NP degradation pathway (Fig. 1), we postulated that the products of ORF2 to -4 were involved in 4-NP catabolism as 4-NP monooxygenase and hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase.

FIG. 2.

(A) Organization of the ORFs found in R. opacus SAO101 and the nucleotide sequence region used for expression in E. coli. The large arrows indicate the size and the direction of each ORF. The small arrows indicate the region cloned into pET17b for gene expression. The direction of the cloned genes was identical to that of the T7 promoter of pET17b. (B) RT-PCR analysis of PCR-amplified gene fragment npcC. Total RNAs isolated from 4-NP-grown SAO101 cells (lanes 1 and 2) and from LB-grown cells (lanes 3 and 4) were used as the templates. Lanes 2 and 4, reactions performed without reverse transcriptase as a control. Lane M, molecular size markers. (C) RT-PCR analysis of ORF2 to -4 (npcBAC). Total RNA isolated from 4-NP-grown SAO101 cells was used as the template. Primer sets A to E for amplification of an internal fragment of ORF1, an internal fragment of ORF2, an internal fragment of ORF3, a spanning region of ORF1 and ORF2, and a spanning region of ORF1 and ORF2, respectively, were used (lanes A to E, respectively). Lanes M, molecular size markers.

TABLE 2.

BLAST homology search results for deduced amino acid sequences

| Protein | Homolog (% identity, score) | Function | Origin | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1 | NodD (33, 131) | Transcriptional regulator for nod genes (LysR type) | Rhizobium sp. strain HW17b | AAA85282 |

| NodD3 (33, 131) | Transcriptional regulator for nod genes (LysR type) | Rhizobium leguminosarum | P23720 | |

| ORF2 (NpcB) | PheA2 (32, 98.2) | Phenol 2-hydroxylase component B (reductase) | Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius A7 | AAF66547 |

| NtaB (37, 97.8) | Nitrilotriacetate monooxygenase component B (reductase) | Chelatobacter heintzii ATCC 29600 | P54990 | |

| ORF3 (NpcA) | TcpA (44, 421) | 2,4,6-TCP monooxygenase | Ralstonia eutropha JMP134 | AAM55214 |

| HadA (42, 411) | Chlorophenol 4-hydroxylase | Ralstonia pickettii DTP0602 | BAA13105 | |

| TftD (44, 406) | Chlorophenol 4-monooxygenase component 2 | Burkholderio cepacia AC1100 | AAC23548 | |

| ORF4 (NpcC) | ORF2 (76, 450) | Hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase | Arthrobacter sp. strain BA-5-17 | BAA82713 |

| HadC (52, 265) | Hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase | Ralstonia pickettii DTP0602 | BAA13107 | |

| TcpC (50, 262) | 6-Chlorohydroxyquinol-1,2-dioxygenase | Rolstonia euiropha JMP134 | AAM55216 | |

| DxnF (46, 249) | Hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase | Sphingomonas wittichi RW1 | CAA51371 | |

| TftH (43, 227) | Chlorohydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase | Burkholderia cepacia AC1100 | I40182 | |

| ORF5 | SCO7191 (47, 202) | Putative secreted protein | Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) | NP_631249 |

| mlr0977 (48, 214) | Putative protein | Mesorhizobium loti | NP_102662 | |

| ORF6 | SAV1362 (65, 166) | Putative transcriptional regulator (YjeB/Rrf2 type) | Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 | NP_822537 |

| mll1642 (46, 107) | Putative transcriptional regulator (YjeB/Rrf2 type) | Mesorhizobium loti | NP_103182 | |

| ORF7 | SMc00182 (55, 154) | Putative transcriptional regulator (SoxR/MerR type) | Sinorhizobium meliloti | NP_385930 |

| PA2273 (55, 153) | Putative transcriptional regulator (SoxR/MerR type) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 | NP_250963 | |

| ORF8 | Rv1634 (47, 129) | Putative drug transporter | Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | NP_216150 |

| RSc2324 (37, 110) | Putative transmembrane protein | Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000 | NP_520445 |

Transcription of ORF2, ORF3, and ORF4 in 4-NP-grown cells of strain SAO101.

To determine whether the genes were transcribed in 4-NP-grown cells of strain SAO101, RT-PCR analysis was performed with total RNA extracted from strain SAO101 cells grown on 4-NP. Total RNA extracted from SAO101 cells grown on LB medium was used as a control. With the use of primer set C (see Materials and Methods), a fragment of approximately 570 bp was amplified from the total RNA extracted from 4-NP-grown cells, but this fragment was not amplified from LB-grown cells (Fig. 2B). These results suggested that the identified genes were involved in the 4-NP catabolic pathway. RT-PCR analysis of ORF2 to -4 was also performed in order to clarify the transcriptional features of the genes. Total RNA extracted from 4-NP-grown cells of strain SAO101 was used as the template, and five oligonucleotide sets (A to E) were used as the PCR primers (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 2C, RT-PCR with each of the primer sets amplified DNA fragments of the expected sizes in this experiment. These results indicated that ORF2 to -4 are transcribed as a single operon and that the transcription is induced in the presence of 4-NP or its metabolite(s). We then designated ORF2 to -4 the nitrophenol catabolic genes npcB, npcA, and npcC, respectively.

Expression of npc genes in E. coli.

To confirm the expression of the npc genes isolated from strain SAO101 in E. coli cells, plasmid pETnpcB containing npcB, pETnpcA containing npcA, pETnpcC containing npcC, and pETnpcBA containing npcBA were constructed by using expression vector pET17b (Table 1 and Fig. 2A), and these plasmids were introduced into E. coli Rosetta(DF3)pLysS. Each clone was IPTG induced, and the crude cell extracts were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis. Distinctive overexpressed proteins with molecular masses of approximately 23.4, 60.0, and 37.8 kDa were observed in E. coli harboring pETnpcB, pETnpcA, and pETnpcC, respectively (data not shown). The sizes of these overexpressed proteins were consistent with the expected sizes of the gene products of npcB (20.1 kDa), npcA (59.7 kDa), and npcC (33.2 kDa), respectively. Unexpectedly, only one overexpressed protein, thought to be NpcB, was observed in E. coli carrying pETnpcBA.

Crude cell extract enzyme assay of E. coli harboring npcB, npcA, and npcC.

In order to characterize the function of the npc gene products, crude cell extract enzyme assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. As described above, npcB and npcA were presumed to encode 4-NP monooxygenase and npcC was presumed to encode a hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase. The enzyme assay of NpcBA with crude cell extract was done by measuring the depletion of the substrate (Table 3). Neither the crude cell extract of E. coli harboring npcB nor that of E. coli harboring npcA transformed 4-NP. Transformation of 4-NP was achieved only when the reaction was performed with a mixture of the crude cell extracts of E. coli harboring npcB and npcA. The results clearly indicated that both npcB and npcA are indispensable for 4-NP conversion. A small amount of hydroxyquinol, which appeared to be an intermediate of the 4-NP degradation pathway, was identified in the reaction mixture by GC-MS analysis. No other metabolite was detected in the reaction mixture. Transformation activity was also observed when 4-NCA and 2,4,6-TCP, as well as 4-NP, were used as substrates. On the other hand, 2,4,6-trinitrophenol was not transformed (Table 3). In this experiment, 4-NP and 4-NCA were transformed at almost same efficiency, and hydroxyquinol was also detected when 4-NCA was used as a substrate. Similar observations were reported for components A and B of the two-component monooxygenase system from Bacillus sphaericus JS905 (11). In strain JS905, both components A and B of 4-NP monooxygenase were essential for the transformation activity, and 4-NP was transformed to 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone via 4-NCA by same monooxygenase system. The 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone was presumed to then be converted to hydroxyquinol by an unidentified (nonspecific) quinone reductase. On the basis of previously reported information and our results, although 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone was not detected, 4-NP degradation in strain SAO101 is likely to be catalyzed by an npcB- and npcA-encoding monooxygenase to form 4-NCA, and then 4-NCA would be converted into 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone by the same monooxygenase. The generated 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone might also be converted to hydroxyquinol by an unidentified quinone reductase in both strain SAO101 and crude cell extract of E. coli.

TABLE 3.

Conversion of phenolic compounds by npcB and npcA gene products in crude cell extract of E. coli

| Substrate | Sp act (pmol/μg of protein/min)a | Relative activityb |

|---|---|---|

| 4-NP | 26.4 ± 2.2 | 100 |

| 4-NCA | 25.0 ± 2.3 | 95 |

| 2,4,6-TNPc | <0.1 | |

| 2,4,6-TCP | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 17 |

Results are the mean of three independent experiments with standard deviations noted.

Relative activity was standardized by setting the activity for 4-NP as, 100.

2,4,6-TNP, 2,4,6-trinitrophenol.

The crude cell extract of E. coli harboring npcC converted hydroxyquinol, and the metabolite maleylacetate was identified in the reaction mixture by GC-MS analysis. These results suggested that npcB encodes the reductase component of 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase, npcA encodes the oxygenase component of 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase, and npcC encodes hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase.

Gene inactivation of npcA and npcC in strain SAO101.

To address the functional significance of npc genes in strain SAO101, npc gene-disrupted mutants were constructed and analyzed. Insertional gene disruption was performed by a single-crossover method, as described previously (13). Since illegitimate recombination frequently occurs in Rhodococcus strains, the candidates for the mutants were screened by colony PCR. One genuine npcA mutant and one genuine npcC mutant were obtained from 12 and 28 candidate kanamycin-resistant mutants, respectively, in this study.

An npcC mutant designated strain SDC1 and an npcA mutant designated strain SDA1 were isolated, and the transformation and assimilation of 4-NP, 4-NCA, and hydroxyquinol were examined. Both mutant strains SDC1 and SDA1 completely lost the ability to grow on 4-NP, 4-NCA, and hydroxyquinol. In the resting-cell assay with wild-type strain SAO101, the yellow color of 4-NP disappeared within 3 to 8 h (approximate conversion rate, 125 μM/unit of optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 1 cell/h), and no intermediate had accumulated in the medium (data not shown). Moreover, the yellow-orange color of 4-NCA disappeared within 3 to 8 h, without the accumulation of any intermediate. In contrast, a dark-brown pigment gradually accumulated in the medium after the disappearance of the yellow color of 4-NP and the yellow-orange color of 4-NCA in the resting-cell assays with strain SDC1. This dark-brown pigment was identified as hydroxyquinol by GC-MS analysis. In the resting-cell assay with strain SDA1, 4-NP gradually changed into a yellow-orange compound after 2 days of incubation (approximate conversion rate, 250 μM/OD600 unit = 1 cell/day); further conversion was not observed, even after longer incubation periods. The yellow-orange compound was identified as 4-NCA by GC-MS analysis. In the resting-cell assay of strain SDA1, 4-NCA was not transformed. These results revealed that the npc genes were functionally active and absolutely essential for 4-NP mineralization in strain SAO101.

Even in the resting-cell assay of the npcA-disrupted stain SDA1, 4-NP was converted slowly to 4-NCA. These observations suggest the existence of another 4-NP degradation gene(s) in strain SAO101. The unknown gene product might transform 4-NP to 4-NCA but might not further convert 4-NCA.

Localization of npc genes.

Many aromatic degradation genes are known to be encoded on plasmid DNAs (3, 6, 21, 22, 29-31). In particular, several Rhodococcus strains harbor aromatic degradation genes on large linear plasmids (4, 15, 24). Three strains of 4-NP-degrading bacteria, i.e., Arthrobacter protophomiae RJK100 (3), B. cepacia RJK200 (21), and Arthrobacter aurescens TW17 (8), have been reported to harbor plasmids involved in 4-NP degradation. In order to confirm the localization of the npc genes on replicons of strain SAO101, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and Southern hybridization against the PFGE-separated DNAs with an npcC probe were performed. The PFGE analysis revealed that strain SAO101 had three large linear plasmids, designated pWK301 (1,100 kb), pWK302 (1,000 kb), and pWK303 (700 kb) (N. Kimura, W. Kitagawa, and Y. Kamagata, submitted for publication). By Southern hybridization analysis, a unique positive hybridization signal was observed at the position of the origin of electrophoresis (data not shown). This result indicated that the npc genes were encoded on chromosomal DNA.

DISCUSSION

We successfully isolated the 4-NP metabolic genes, i.e., npcBAC, from a gram-positive bacterium, R. opacus SAO101. In the present study, a mixture of NpcB and NpcA converted 4-NP to hydroxyquinol and also converted 4-NCA to hydroxyquinol; moreover, NpcC converted hydroxyquinol to malelylacetate in a crude cell extract of E. coli. Based on these results and the structural information regarding the enzymes involved, the npcB gene encodes the reductase component of 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase, the npcA gene encodes the oxygenase component of 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase, and the npcC gene encodes hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase. This is the first study to isolate and characterize the 4-NP degradation genes that convert 4-NP to maleylacetate via the hydroxyquinol pathway.

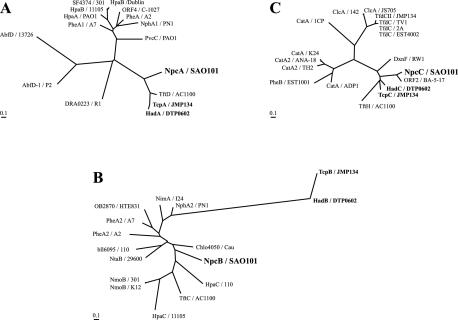

The deduced amino acid sequences and gene organization of the npcBAC genes from strain SAO101 indicate an evolutionary relationship with the 2,4,6-TCP degradation genes tcpABC from R. eutropha JMP134 (16) and hadABC from R. pickettii DTP0602 (9, 27). However, some differences were noted. The reductase component npcB of strain SAO101 was located upstream of the oxygenase component npcA, in contrast to the finding that putative reductase component genes tcpB and hadB were located downstream of the oxygenase component genes tcpA and hadA of R. eutropha JMP134 and R. pickettii DTP0602, respectively. The deduced amino acid sequences of npcA and npcC showed 42 to 52% identity with the corresponding tcpA and tcpC genes and hadA and hadC genes; however, the deduced amino acid sequence of npcB showed much lower identity, i.e., 30 and 27%, to the corresponding tcpB and hadB amino acid sequences. The phylogenetic trees of the NpcA, NpcB, and NpcC proteins are shown in Fig. 3. As shown in these trees, NpcA, TcpA, and HadA are in the same branch, and they seem to comprise a nitro- or chloro-substituted phenol oxygenase family (Fig. 3A). Moreover, NpcC, TcpC, and HadC are in the same branch as members of the hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase family (Fig. 3C). The present results indicate that these proteins are closely related. On the other hand, NpcB is apparently distant from TcpB and HadB (Fig. 3B). From an evolutionary perspective, these findings indicate that the reductase gene npcB has a relationship to the tcp and had genes that is more distant than the evolutionary relationship of the corresponding monooxygenase genes (npcA, tcpA, and hadA) and the corresponding hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase genes (npcC, tcpC, and hadC). It should also be noted that different characteristics of the reductase were also observed in our enzyme activity experiments. Purified TcpA protein did not show monooxygenase activity by itself; however, in the presence of E. coli flavin reductase, it showed monooxygenase activity. In the case of HadA, the crude cell extract of HadA-expressing E. coli did not require HadB for monooxygenase activity. Both of these results suggest that reductase originating from E. coli could be substituted for the original reductase (probably TcpB and HadB) in order to obtain monooxygenase activity. In contrast, both NpcB and NpcA of strain SAO101 were found to be indispensable for monooxygenase activity in the crude cell extract of E. coli. These results indicate that no reductase originating from E. coli in the crude cell extract could be substituted to achieve monooxygenase activity.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic trees of NpcA (A), NpcB (B), and NpcC (C) proteins. Protein and strain abbreviations and accession numbers: NpcA/SAO101, nitrophenol monooxygenase oxygenase component of R. opacus SAO101 (AB154422); TcpA/JMP134, chlorophenol monooxygenase of R. eutropha JMP134 (AF498371); HadA/DTP0602, chlorophenol monooxygenase of R. pickettii DTP0602 (D86544); TftD/AC1100, chlorophenol monooxygenase component 2 of B. cepacia AC1100 (U83405); NphA1/PN1, 4-nitrophenol hydroxylase component A of Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1 (AB081773); PheA1/A7, phenol 2-hydroxylase component A of G. thermoglucosidasius A7 (AF140605); PheA/A2, phenol 2-hydroxylase component A of Geobacillus thermoleovorans A2 (AAC38324); PvcC/PAO1, pyoverdine biosynthesis protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (AAC21673); ORF4/C-1027, chlorophenol-4-monooxygenase of Streptomyces globisporus C-1027 (AAL06674); HpaB/Dublin, 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase large chain of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Dublin (AAD53503); SF4374/301, 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase large chain of Shigella flexneri 2a strain 301 (NP_710083); HpaB/11105, 4-hydroxyphenylacetic hydroxylase of E. coli ATCC 11105 (Z29081), HpaA/PAO1, 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase large chain of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (NP_252780); AbfD/13726, 4-hydroxybutyryl coenzyme A dehydratase of Clostridium aminobutyricum ATCC 13726 (P55792); AbfD-1/P2, 4-hydroxybutyryl coenzyme A dehydratase of Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 (NP_343847); DRA0223/R1, 4-hydroxyphenylacetate-3-hydroxylase of Deinococcus radiodurans R1 (NP_285546); NpcB/SAO101, nitrophenol monooxygenase reductase component of R. opacus SAO101 (AB154422); TcpB/JMP134, putative reductase of R. eutropha JMP134 (AF498371); HadB/DTP0602, putative reductase of R. pickettii DTP0602 (D86544); TftC/AC1100, chlorophenol monooxygenase component 1 of B. cepacia AC1100 (U83405); NphA2/PN1, 4-nitrophenol hydroxylase component B of Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1 (AB081773); PheA2/A7, phenol 2-hydroxylase component B of G. thermoglucosidasius A7 (AF140605); PheA2/A2, phenol 2-hydroxylase component B of G. thermoleovorans A2 (AAQ04677); NtaB/29600, nitrilotriacetate monooxygenase component B of Chelatobacter heintzii ATCC 29600 (U39411); Chlo4050/Cau, putative reductase of Chloroflexus aurantiacus (ZP_00020998); bll6095/110, putative nitrilotriacetate monooxygenase of Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 (NP_772735); OB2870/HTE831, phenol 2-hydroxylase component B of Oceanobacillus iheyensis HTE831 (NP_693792); NmoB/K12, 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase small chain of E. coli K-12 (BAA35774); NmoB/301, 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase small chain of S. flexneri 2a strain 301 (NP_706929); HpaC/110, putative monooxygenase of B. japonicum USDA 110 (NP_773930); NimA/I24, putative reductase of Rhodococcus sp. strain I24 (AAL61657); HpaC/11105, 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase oxidoreductase component of E. coli ATCC 11105 (Z29081); NpcC/SAO101, hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase of R. opacus SAO101 (AB154422); TcpC/JMP134, hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase of R. eutropha JMP134 (AF498371); HadC/DTP0602, hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase of R. pickettii DTP0602 (D86544); TftH/AC1100, hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase of B. cepacia AC1100 (U19883); DxnF/RW1, hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase of S. wittichi RW1 (CAA51371); ORF2/BA-5-17, hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase of Arthrobacter sp. strain BA-5-17 (BAA82713); TfdC/EST4002, chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase of Achromobacter denitrificans EST4002 (AAC78501); TfdC/2A, chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase of B. cepacia 2A (AAK81678); TfdC/TV1, catechol 1,2-dioxygenase II of Variovorax paradoxus TV1 (BAA88069); TfdCII/JMP134, chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase of R. eutropha JMP134 (AAC44730); ClcA/JS705, chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase of Ralstonia sp. strain JS705 (CAA06968); ClcA/142, chlorocatechol-1,2-dioxygenase of P. aeruginosa 142 (AAF00195); CatA/1CP, catechol 1,2-dioxygenase of R. opacus 1CP (CAA67941); CatA/K24, catechol 1,2-dioxygenase of Acinetobacter lwoffii K24 (AAC31767); CatA2/ANA-18, catechol 1,2-dioxygenase of Frateuria sp. strain ANA-18 (T48871); CatA2/TH2, catechol 1,2-dioxygenase of Burkholderia sp. strain TH2 (BAC16769); PheB/EST1001, catechol 1,2-dioxygenase of Pseudomonas sp. strain EST1001 (P31019); CatA/ADP1, catechol 1,2-dioxygenase of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (AAC46426).

In the phylogenetic tree, both the NpcB and NpcA proteins are located in branches that differ from those of the 4-NP monooxygenase protein NphA2 (reductase) and NphA1 (oxygenase) of Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1 (26). This might be reflective of enzyme function. NpcBA of strain SAO101 converts 4-NP to hydroxyquinol probably via 4-NCA, whereas NphA1A2 of strain PN1 simply converts 4-NP to 4-NCA. These results indicate that NpcBA of strain SAO101 and NphA1A2 of strain PN1 are in fact entirely different enzymes.

A two-component 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase protein from B. sphaericus JS905 has been characterized (11). The npcBA gene products of strain SAO101 and the 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase proteins of strain JS905 seem to have some features in common. Since the genes that encode components A and B from strain JS905 were not cloned and the structural information for these proteins was not addressed in this report, we were unable to compare the amino acid sequences and molecular sizes of the 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase proteins of strains JS905 and SAO101.

The npcA and npcC genes were successfully inactivated by the insertion of a kanamycin resistance gene. The resulting mutant strains, strains SDA1 and SDC1, completely lost the ability to grow on 4-NP and 4-NCA as the sole carbon source. This finding clearly indicates that npcA and npcC are essential for 4-NP mineralization in strain SAO101. When npcA mutant strain SDA1 was incubated in minimal medium together with 4-NP, an accumulation of 4-NCA was observed as a dead-end product. Accordingly, another 4-NP monooxygenase gene apparently played a role in the transformation of 4-NP to 4-NCA in strain SAO101. A preliminary study indicated that strain SAO101 has a Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1-type 4-NP monooxygenase gene (nphA1). A PCR experiment to amplify the partial nphA1 was carried out, and the amplified 528-bp nucleotide sequence showed 99% identity with nphA1 of strain PN1 (data not shown). The identified nphA-type gene in strain SAO101, designated nphASAO, might have contributed as the second 4-NP degradation gene in strain SAO101, as weak transformation of 4-NP to 4-NCA was observed in strain SDA1. Considering the 4-NP conversion velocities of the wild type and the npcA mutant (125 μM/OD600 [1 cell/h] and 250 μM/OD600 [1 cell/day], respectively), strain SAO101 seemed to convert 4-NP primarily by the npc gene products. In addition, strain SDA1 could not utilize 4-NP as a carbon source, and therefore npc genes were essential for 4-NP transformation and mineralization in strain SAO101.

The proposed 4-NP degradation pathway and corresponding genes for the enzymes of strain SAO101 are as follows. The metabolic transformation of 4-NP is initiated by monooxygenation with npcBA-encoded 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase and nphASAO-encoded 4-NP monooxygenase to form 4-NCA. The 4-NCA produced is converted to 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone by npcBA-encoded 4-NP/4-NCA monooxygenase. The generated 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone might be converted to hydroxyquinol by an unidentified quinone reductase. The hydroxyquinol is then converted to maleylacetate by npcC-encoded hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase. This scheme is among the most conceivable pathways. Another probable intermediate of mono-oxidized 4-NP is 4-nitroresorcinol. The potential intermediate 4-nitroresorcinol could not be used as the substrate for the NpcBA enzyme assay because it was not possible to obtain this product commercially. We have therefore not yet ruled out 4-nitroresorcinol as an intermediate.

In this study, multiple genes for the initial degradation of 4-NP were identified. Further study will reveal the entire 4-NP degradation pathway and genes of strain SAO101, including the genes for unidentified intermediates (such as 4-NCA/4-nitroresorcinol and 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone), the npc genes, and the nphASAO genes, and the mechanism of their regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Masao Fukuda and Hisashi Kudo for their help with the PFGE analysis.

This work was supported by a grant from the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO). W. Kitagawa was supported by a NEDO fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 1992. Toxicological profile for nitrophenol. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

- 2.Armengaud, J., K. N. Timmis, and R. M. Wittich. 1999. A functional 4-hydroxysalicylate/hydroxyquinol degradative pathway gene cluster is linked to the initial dibenzo-p-dioxin pathway genes in Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. J. Bacteriol. 181:3452-3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chauhan, A., A. K. Chakraborti, and R. K. Jain. 2000. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-nitrophenol and 4-nitrocatechol by Arthrobacter protophormiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabrock, B., M. Kesseler, B. Averhoff, and G. Gottschalk. 1994. Identification and characterization of a transmissible linear plasmid from Rhodococcus erythropolis BD2 that encodes isopropylbenzene and trichloroethene catabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:853-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daubaras, D. L., K. Saido, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1996. Purification of hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase and maleylacetate reductase: the lower pathway of 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid metabolism by Burkholderia cepacia AC1100. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4276-4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Don, R. H., and J. M. Pemberton. 1981. Properties of six pesticide degradation plasmids isolated from Alcaligenes paradoxus and Alcaligenes eutrophus. J. Bacteriol. 145:681-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffner, F. M., U. Kirchner, M. P. Bauer, and R. Muller. 2000. Phenol/cresol degradation by the thermophilic Bacillus thermoglucosidasius A7: cloning and sequence analysis of five genes involved in the pathway. Gene 256:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanne, L. F., L. L. Kirk, S. M. Appel, A. D. Narayan, and K. K. Bains. 1993. Degradation and induction specificity in actinomycetes that degrade p-nitrophenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3505-3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatta, T., O. Nakano, N. Imai, N. Takizawa, and H. Kiyohara. 1999. Cloning and sequence analysis of hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase gene in 2,4,6-trichlorophenol-degrading Ralstonia pickettii DTP0602 and characterization of its product. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 87:267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain, R. K., J. H. Dreisbach, and J. C. Spain. 1994. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol via 1,2,4-benzenetriol by an Arthrobacter sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3030-3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadiyala, V., and J. C. Spain. 1998. A two-component monooxygenase catalyzes both the hydroxylation of p-nitrophenol and the oxidative release of nitrite from 4-nitrocatechol in Bacillus sphaericus JS905. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2479-2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura, N., and Y. Urushigawa. 2001. Metabolism of dibenzo-p-dioxin and chlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin by a gram-positive bacterium, Rhodococcus opacus SAO 101. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 92:138-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitagawa, W., K. Miyauchi, E. Masai, and M. Fukuda. 2001. Cloning and characterization of benzoate catabolic genes in the gram-positive polychlorinated biphenyl degrader Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. J. Bacteriol. 183:6598-6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitagawa, W., S. Takami, K. Miyauchi, E. Masai, Y. Kamagata, J. M. Tiedje, and M. Fukuda. 2002. Novel 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid degradation genes from oligotrophic Bradyrhizobium sp. strain HW13 isolated from a pristine environment. J. Bacteriol. 184:509-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosono, S., M. Maeda, F. Fuji, H. Arai, and T. Kudo. 1997. Three of the seven bphC genes of Rhodococcus erythropolis TA421, isolated from a termite ecosystem, are located on an indigenous plasmid associated with biphenyl degradation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3282-3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louie, T. M., C. M. Webster, and L. Xun. 2002. Genetic and biochemical characterization of a 2,4,6-trichlorophenol degradation pathway in Ralstonia eutropha JMP134. J. Bacteriol. 184:3492-3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munnecke, D. M. 1976. Enzymatic hydrolysis of organophosphate insecticides, a possible pesticide disposal method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 32:7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munnecke, D. M., and D. P. Hsieh. 1974. Microbial decontamination of parathion and p-nitrophenol in aqueous media. Appl. Microbiol. 28:212-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munnecke, D. M., and D. P. Hsieh. 1976. Pathways of microbial metabolism of parathion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 31:63-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami, S., T. Okuno, E. Matsumura, S. Takenaka, R. Shinke, and K. Aoki. 1999. Cloning of a gene encoding hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase that catalyzes both intradiol and extradiol ring cleavage of catechol. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63:859-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prakash, D., A. Chauhan, and R. K. Jain. 1996. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-nitrophenol by Pseudomonas cepacia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 224:375-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romine, M. F., L. C. Stillwell, K. K. Wong, S. J. Thurston, E. C. Sisk, C. Sensen, T. Gaasterland, J. K. Fredrickson, and J. D. Saffer. 1999. Complete sequence of a 184-kilobase catabolic plasmid from Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199. J. Bacteriol. 181:1585-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharmila, M., K. Ramanand, and N. Sethunathan. 1989. Effect of yeast extract on the degradation of organophosphorus insecticides by soil enrichment and bacterial cultures. Can. J. Microbiol. 35:1105-1110. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimizu, S., H. Kobayashi, E. Masai, and M. Fukuda. 2001. Characterization of the 450-kb linear plasmid in a polychlorinated biphenyl degrader, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2021-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spain, J. C., and D. T. Gibson. 1991. Pathway for biodegradation of para-nitrophenol in a Moraxella sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:812-819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeo, M., T. Yasukawa, Y. Abe, S. Niihara, Y. Maeda, and S. Negoro. 2003. Cloning and characterization of a 4-nitrophenol hydroxylase gene cluster from Rhodococcus sp. PN1. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 95:139-145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takizawa, N., H. Yokoyama, K. Yanagihara, T. Hatta, and H. Kiyohara. 1995. A locus of Pseudomonas pickettii DTP0602, had, that encodes 2,4,6-trichlorophenol-4-dechlorinase with hydroxylase-activity, and hydroxylation of various chlorophenols by the enzyme. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 80:318-326. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas, P. M., K. F. Golly, R. A. Virginia, and J. W. Zyskind. 1995. Cloning of nod gene regions from mesquite rhizobia and bradyrhizobia and nucleotide sequence of the nodD gene from mesquite rhizobia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3422-3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Meer, J. R., A. R. van Neerven, E. J. de Vries, W. M. de Vos, and A. J. Zehnder. 1991. Cloning and characterization of plasmid-encoded genes for the degradation of 1,2-dichloro-, 1,4-dichloro-, and 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene of Pseudomonas sp. strain P51. J. Bacteriol. 173:6-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vedler, E., V. Koiv, and A. Heinaru. 2000. TfdR, the LysR-type transcriptional activator, is responsible for the activation of the tfdCB operon of Pseudomonas putida 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid degradative plasmid pEST4011. Gene 245:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worsey, M. J., F. C. Franklin, and P. A. Williams. 1978. Regulation of the degradative pathway enzymes coded for by the TOL plasmid (pWWO) from Pseudomonas putida mt-2. J. Bacteriol. 134:757-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zylstra, G. J., S.-W. Bang, L. M. Newman, and L. L. Perry. 2000. Microbial degradation of mononitrophenols and mononitrobenzoates, p. 145-160. In J. C. Spain, J. B. Hughes, and H. J. Knackmuss (ed.), Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.