The natural history of NMDA receptor (NMDAR) antibody encephalitis in adults and children is altered by treatment with immunosuppressive therapy or tumor removal.1 In adult cohorts, early initiation of immunotherapy appears to be beneficial.1,2 In the largest series to date, Titulaer et al.1 demonstrated that earlier treatment was associated with a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 2 or less in a cohort of 501 adults and children (univariate analysis p = 0.009, multivariable analysis p < 0.0001). Multivariable analysis on 177 children within the cohort showed that earlier treatment was associated with an mRS score of 2 or less, although this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.067).1 An mRS score of 2 indicates slight disability and that the patient is unable to carry out all previous activities.

We performed a literature review of all first presentation cases of pediatric NMDAR antibody encephalitis to determine whether early treatment with immunomodulatory therapy is associated with a better outcome (see search criteria in appendix e-1 at Neurology.org/nn).

From 43 articles identified (appendix e-1, figure e-1), information was available on 80 children ≤17 years of age (56 female, median age 8 years, interquartile range [IQR] 4–14 years, range 1.3–17 years) reported across 34 articles with care from at least 34 institutions (table e-1). We dichotomized outcome into complete recovery (pediatric mRS score = 0) or incomplete recovery (mRS score ≥ 1).

Fifty-seven percent (41) received IV steroids as the first agent, 11.3% (9) received IV immunoglobulin (IVIg), 28.7% (23) had IVIg and methylprednisolone simultaneously, 2 children had tumor removal, and 5 children had no treatment (appendix e-1).

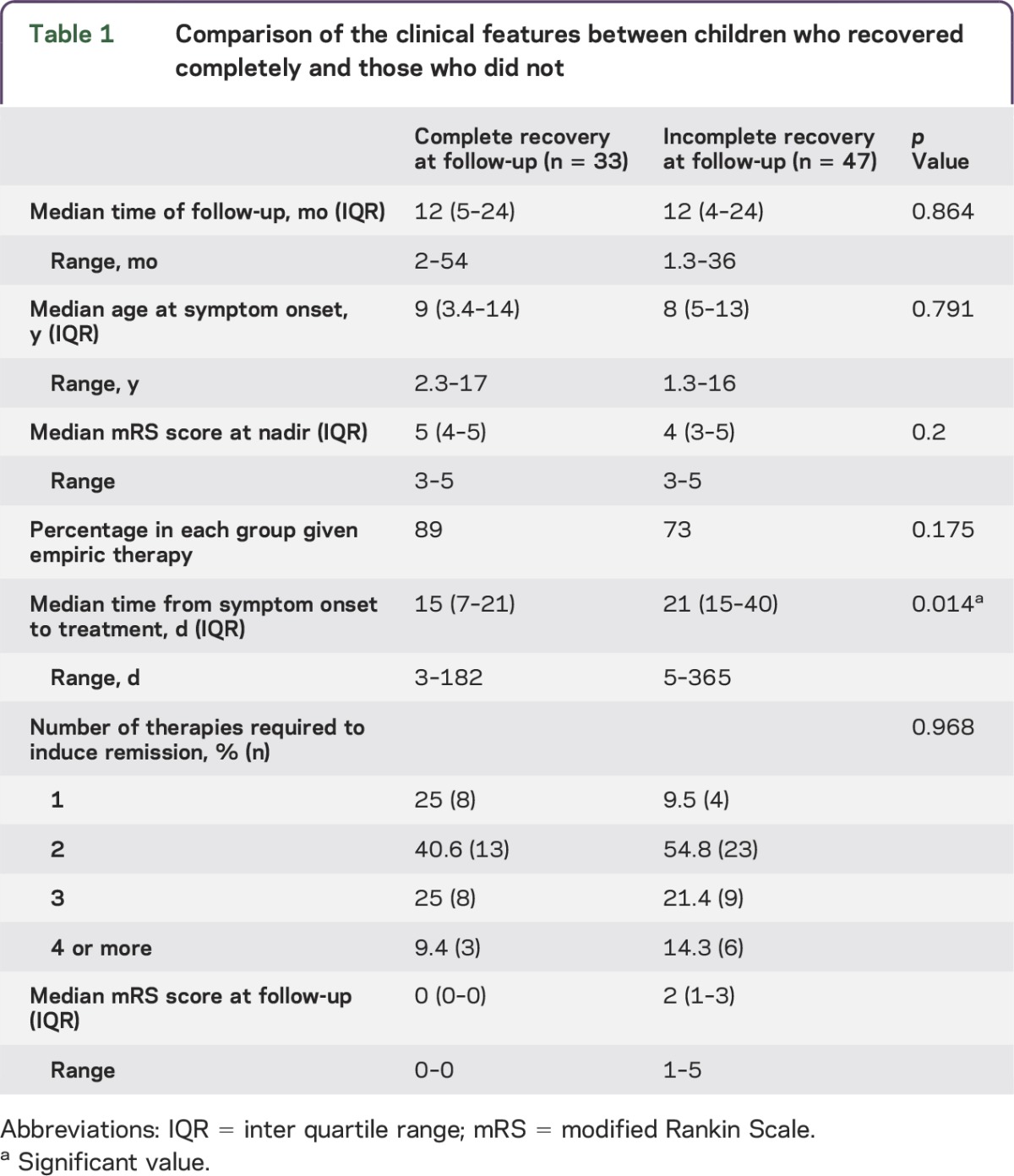

At follow-up (median 12 months, IQR 4.5–24 months, range 1.3–54 months), 33 (41%) children had recovered completely (mRS score = 0), whereas 47 (59%) children had an incomplete recovery (mRS score ≥ 1) based on evaluation by their treating physicians and/or families. There was no difference in median time to follow-up or median age at onset between children who recovered fully and those who did not (see table 1). There was no difference in median mRS score at nadir between children who made a full recovery (mRS score 5, IQR 4–5, range 3–5) and children who made an incomplete recovery (mRS score 4, IQR 3–5, range 3–5) (p = 0.2).

Table 1.

Comparison of the clinical features between children who recovered completely and those who did not

The important finding from this review is that the median time from symptom onset to initiation of treatment was 15 days (IQR 7–21 days, range 3–182 days) in children who recovered completely (mRS score = 0) and 21 days (IQR 15–40 days, range 5–365 days) in those who had not recovered completely at follow-up (p = 0.014, Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney nonparametric test).

We illustrate the direct correlation between outcome and days to initiation of treatment as a box plot (see figure e-2).

Discussion.

Our retrospective review suggests that earlier treatment of NMDAR antibody encephalitis in children results in better outcomes. This is consistent with a previous report by Titulaer et al.1 In our study, children who recovered completely at follow-up (mRS score = 0) were treated a median of 15 days from symptom onset vs 21 days in children who did not completely recover. The median time of follow-up was 1 year in all patients, and because recovery from NMDAR antibody encephalitis can be very slow and take 18 months or longer,1 some patients may recover further. As such, our data may simply reflect an earlier recovery, which nevertheless may have a large benefit on quality of life and educational attainment. Although NMDAR antibody has been shown to mediate its effect by receptor internalization, which is reversible,3 factors such as the extent of secondary disturbance in synaptogenesis as a result of NMDAR binding by antibodies,4 manifesting as persisting functional and structural advanced MRI changes,5 may exert a larger influence on the developing CNS.

There are limitations to this study. First, selection bias may arise from reporting bias and the subsequent limited author response allowing analysis of only 80 of the potential 300 cases. Single cases are often published because of atypical features, and our study included 23 case reports. Second, 29 of the 80 patients were diagnosed on serum analysis alone, which may yield false-positive results6; however, patients included in this study did have a clinical phenotype compatible with NMDAR encephalitis. Third, the outcome is dichotomous—the mRS was designed to describe outcomes in the context of stroke in adults, focusing primarily on physical deficits, and is not a sensitive marker of cognitive deficits.

Prospective longitudinal studies addressing these limitations will be required to confirm whether earlier treatment results in better measurable outcomes.

Early recognition of the variable symptoms of NMDAR antibody encephalitis and more widespread availability of rapid diagnostic tests7 will facilitate early initiation of optimal therapy, although empiric therapy may be warranted when children have clinical manifestations that are consistent with NMDAR and other autoimmune encephalitis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Drs. Roberta Biancheri, Blaithnaid McCoy, Sarbani Raha, David Cohen, Sebastian Lebon, Ming-Chi Lai, Darcy Krueger, Johan Penzien, and Mered Parnes for providing additional patient data.

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/nn

Author contributions: Susan Byrne designed the study, collected the data, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Cathal Walsh contributed to study design and data analysis and edited the manuscript. Yael Hacohen assisted with data collection and edited the manuscript. Eyal Muscal assisted with data collection and edited the manuscript. Joseph Jankovic assisted with data collection and edited the manuscript. Amber Stocco assisted with data collection and edited the manuscript. Russell C. Dale contributed to data analysis, interpretation, and collection and edited the manuscript. Angela Vincent contributed to data analysis, interpretation, and collection and edited the manuscript. Ming Lim contributed to study design, contributed to data analysis, interpretation, and collection, and wrote the manuscript. Mary King contributed to study design and wrote the manuscript.

Study funding: This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre based at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust and the University of Oxford.

Disclosure: S. Byrne reports no disclosures. C. Walsh received research support from Health Research Board. Y. Hacohen received research support from the NIHR. E. Muscal received research support from Lupus Foundation of America. J. Jankovic is on the scientific advisory board for Allergan Inc, Auspex Pharmaceuticals Inc, Impax Pharmaceuticals, Ipsen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Merz Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, UCB Inc, and US World Meds; is on the editorial board for Medlink: Neurology, Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, Neurology in Clinical Practice, The Botulinum Journal, PeerJ, Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders, Neurotherapeutics, Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements, Journal of Parkinson's Disease, and UpToDate; receives publishing royalties from Cambridge, Elsevier, Hodder Arnold, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, and Wiley-Blackwell; is employed by Allergan Inc, Ipsen Limited, Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson Research, Merz Pharmaceuticals, Ovation Pharmaceuticals, and Teva; has consulted for Allergan Inc, Auspex Pharmaceuticals Inc, Impax Pharmaceuticals, Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals Inc, Lundbeck Inc, Merz Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, UCB Inc, and US World Meds; and received research support from Allergan Inc, Allon Therapeutics, Biotie Therapies Inc, Ceregene Inc, CHDI Foundation, Chelsea Therapeutics, Diana Helis Henry Medical Research Foundation, GE Healthcare, Huntington's Disease Society of America, Huntington Study Group, Impax Pharmaceuticals, Ipsen Limited, Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson Research, Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, Benign Essential Blepharospasm, Lundbeck Inc, Medtronic, Merz Pharmaceuticals, NIH, National Parkinson Foundation, Neurogen, St. Jude Medical, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, UCB Inc, and University of Rochester Parkinson Study Group. A. Stocco received travel funding from Bayer. R.C. Dale is on the research advisory committee for Queensland Children's Medical Institute; received honoraria from Biogen Idec and Bristol-Myers-Squibb; is on the editorial board for Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation, and European Journal of Paediatric Neurology; and received research support from NHMRC and Multiple Sclerosis Research Australia. A. Vincent is on the editorial board for Neurology; was an associate editor for Brain; holds a patent for LGI1/CASPR2 antibodies and for GABAAR antibodies; receives royalties from Athena Diagnostics, Euroimmun AG, Blackwell Publishing, and MacKeith Press; has consulted for Athena Diagnostics; and received research support from NIHR. M. Lim is on the advisory board for SPARKS Charity, received travel funding from Merck Serono, has consulted for CSL Behring, and received research support from NIHR. M. King reports no disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/nn for full disclosure forms. The Article Processing Charge was paid by the authors.

References

- 1.Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irani SR, Bera K, Waters P, et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate antibody encephalitis: temporal progression of clinical and paraclinical observations in a predominantly non-paraneoplastic disorder of both sexes. Brain 2010;133:1655–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moscato EH, Peng X, Jain A, Parsons TD, Dalmau J, Balice-Gordon RJ. Acute mechanisms underlying antibody effects in anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Ann Neurol 2014;76:108–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mikasova L, De Rossi P, Bouchet D, et al. Disrupted surface cross-talk between NMDA and Ephrin-B2 receptors in anti-NMDA encephalitis. Brain 2012;135:1606–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finke C, Kopp UA, Scheel M, et al. Functional and structural brain changes in anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Ann Neurol 2013;74:284–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zandi MS, Paterson RW, Ellul MA, et al. Clinical relevance of serum antibodies to extracellular N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor epitopes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Epub 2014 Sep 22. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gresa-Arribas N, Titulaer MJ, Torrents A, et al. Antibody titres at diagnosis and during follow-up of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:167–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.