Summary

Concerns about the frequency of failure in late stage drug development have prompted a series of proposals for improving the positive predictivity of trials where clinical activity is first evaluated—typically phase 2 trials. However, many proposed reforms entail ethical and social tradeoffs that might not be immediately apparent. We argue that trial reforms aimed at boosting phase 2 positive predictivity have important repercussions for human subjects, as well as the capacity of the research enterprise to discharge its social mission. We articulate four factors that should guide the level of positive predictivity sought in middle stages of drug development: (1) clinical equipoise and the frequency with which new interventions are successfully translated in a given research area; (2) abundance of other candidates in a drug development pipeline; (3) the vulnerability of populations enrolled in middle stages of drug development; and (4) the social utility of negative phase 3 trials.

For drug development, it is the best of times and the worst of times: basic science continues to generate an abundant supply of novel targets, drug candidates, and combinatorial strategies, yet, few strategies are vindicated in confirmatory testing (i.e. “phase 3” trials), and the cost of these failures continues to soar.

Both the abundance of new strategies in the drug pipeline and their rate of failed translation place extraordinary pressure on stages of drug development where clinical activity is first evaluated—typically through a variety of phase 2 trial methodologies (hereafter abbreviated “phase 2”). The abundant pipeline demands that phase 2 trials quickly evaluate candidates so that none languish on the shelf, while the prospect of heavy subject burdens and costs of phase 3 failures demands that they accurately predict results of subsequent confirmatory trials.

Concerns about phase 2 predictivity—both in terms of accurate and efficient pipeline screening (i.e., negative predictivity) and in terms of reducing phase 3 failures (i.e., positive predictivity)—have prompted a series of innovations in phase 2 trial design. However, many of the contemplated innovations entail ethical and social tradeoffs that might not be apparent. In what follows, we argue that early efficacy trial reforms have important repercussions for the safety and burden of human subjects, as well as the capacity of the research enterprise to discharge its social missions of producing medical knowledge for clinical practice and efficiently vetting promising intervention candidates. Accordingly, we articulate four factors that should guide the level of positive predictivity sought in middle stages of drug development: (1) clinical equipoise and the frequency with which new interventions are successfully translated in a given research area; (2) abundance of other candidates in a drug development pipeline; (3) the vulnerability of populations enrolled in middle stages of drug development; and (4) the social utility of negative phase 3 trials.

Making Phase 2 Trials More Predictive

By one estimate, the cost of a publicly-sponsored phase 3 trial exceeds $1 million on average; an industry-sponsored trial can exceed $20 million.1 Yet, as many as two-thirds of the interventions entering phase 3 fail to reproduce success observed in phase 2 trials.2;3 Ostensibly, this poor rate of translation betrays an inefficient use of research resources and needless burdens imposed on patient-subjects. As one commentator stated provocatively: “[f]ailing in phase 3 means we made the wrong decision to go that far with an agent, and that reflects poor phase 2 design.”4

Concerns about the number of negative phase 3 trials have prompted a series of innovations in phase 2 design. Some of these innovations introduce experimental modules, such as the use of more predictive biomarkers, tiered approaches to outcome assessment, patient enrichment (i.e. where populations are selected on the basis of a biological characteristic- often a molecular marker), use of clinical endpoints, real-time pharmacokinetic analysis, randomization (for areas, like oncology, where phase 2 studies use historical controls), larger sample sizes, or variations in statistical error rates. Other proposals are more wholesale revisions of the phase 2 testing paradigm, such as seamless phase 2/3 designs, which attempt to reduce the lead times between phases and costs of initiating multiple studies by combining early efficacy testing and confirmatory testing into one, continuous trial; and adaptive designs, which test three or more new candidates treatments in a multi-arm study and then eliminate the flagging arms at regular intervals.3–8

But whether modular or wholesale, all of these proposals aim to reduce the number of false positives in phase 2 trials, i.e., reduce the number of ineffective agents that are declared promising in phase 2 studies and advanced into phase 3 testing. This is ethically attractive for two reasons. First, by reducing occurrence of failure in phase 3, it limits the number of patient-volunteers exposed to unsafe and ineffective drugs. Given that the number of patients in phase 3 studies is typically ten fold greater than in phase 2, these reductions in total subject burden can be substantial. Second, more predictive phase 2 trials enable more efficient allocation of resources in clinical translation. By accurately identifying effective agents, such studies can free up material and human resources by focusing their deployment on confirmatory trials that are more likely to meet their endpoints. Spared resources can then be invested in more fruitful investigations.

The Costs of More Predictive Phase 2 Trials for Human Subjects

However, designs aimed at reducing false positives also have costs and burdens for human subjects. Some of the gains in subject welfare described above are potentially offset by greater burden. Introducing randomization in phase 2 studies, for example, roughly doubles the number of patients in phase 2 trials, since they now require comparator arms. Similarly, using enrichment designs, pharmacodyamics, or real-time pharmacokinetics all entail more frequent (and often invasive) tissue collection from volunteers. In areas of vaccine development, the quest for predictive phase 2 designs has kindled interest in phase 2 “challenge studies,” which deliberately infect healthy volunteers with a manageable form of disease.9

These extra burdens in phase 2 are not morally equivalent to those typically encountered in phase 3. Risks of drug administration in phase 3 trials are ethically justified by clinical equipoise—a state of collective uncertainty about whether experimental treatment is preferable to standard care—and hence, can plausibly claim therapeutic value for subjects. In contrast, the case for clinical equipoise is far weaker in initial tests of efficacy, since evidence of clinical utility is lacking at the outset and the background probability of discovering a useful intervention is low at that stage.10 In any event, the risks and burdens of more intensive tissue collection or disease challenge are morally justified by ends that are predominantly external to the volunteer, and this makes them more ethically fraught.

Minimizing phase 2 false positives also threatens clinical equipoise for subsequent phase 3 trials.11 If the pre-test likelihood of successful outcomes are too high, patients randomized to comparators in phase 3 are systematically disadvantaged. Further, knowledge gained per patient enrolled is diminished, since less is learned from the successful prosecution of phase 3 trials.

The Cost of More Predictive Trials for the Research Enterprise

Predictive phase 2 trial designs also entail costs for the integrity of the research enterprise. The social mission of clinical research is to furnish healthcare and public health decision-makers with information and evidence for addressing unmet health needs.12 The delivery of this social good is threatened by any process that destabilizes the types of stakeholder collaboration that are required by clinical research.13 It is also threatened where the finite resources of a research enterprise are not directed in accordance with social priorities. Highly predictive phase 2 designs have potential unintended consequences for each.

First, there are social costs associated with contemplated design innovations. Gains in reducing false positives in phase 2 are potentially at the expense of greater false negatives (i.e., eliminating truly useful agents in phase 2 trials).14 In areas with few candidates and pressing clinical need, this entails large opportunity costs. Further, more predictive designs can strain the capacity of research systems to vet new drug candidates. This is because larger sample sizes, lengthened observation periods, and/or more extensive and real-time laboratory analyses demand greater resources. Though preempted phase 3 studies free up resources for vetting other candidates, some resources cannot be redirected in this way. For example, the financial resources that pharmaceutical firms save by avoiding phase 3 will be distributed according to company priorities, rather than toward upstream investigations of other candidates for the disease.

Second, highly predictive phase 2 studies threaten a fragile social consensus that enables investigators to randomize patients in phase 3 trials, and that allows regulators to condition distribution of new drugs on positive, replicated, trials that have sufficient power to detect at least commonly occurring toxicities. In recent years, this social consensus has come under repeated attack.15;16 The prospect that the efficacy of new drugs can be reliably inferred after phase 2 substantially weakens the moral argument for withholding market access until larger studies are completed. This, in turn, threatens the capacity of the research enterprise to rigorously evaluate drugs before clinical uptake.

Third, negative, adequately powered phase 3 studies often have affirmative scientific and medical value. For agents that have not been licensed, decisively negative results—or safety signals—can inform decision-making for the testing of other drugs in the same class. For licensed drugs that are tested in new indications or in new combinations, adequately powered negative trials warn caregivers against using drugs in specified, off-label applications.

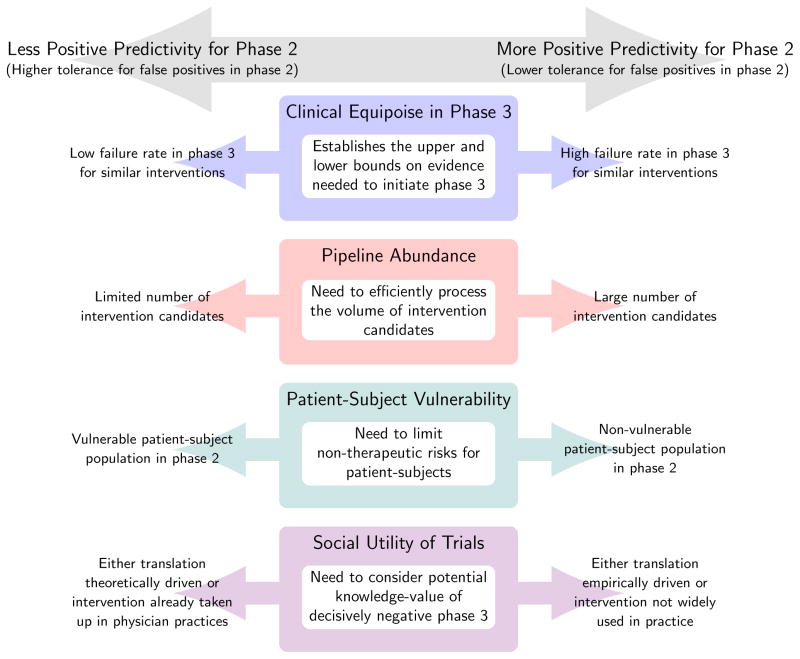

Defining The Optimal Level of Phase 2 Predictivity

Our analysis suggests that, at a certain point, ethical and social gains for reducing false positives in phase 2 are dominated by losses. If so, the task for study planners, funding bodies, sponsors, and others is to determine the optimum level of false positives for phase 2—where the gains in avoiding negative phase 3 trials outweigh the costs described above—and then to deploy policies that encourage trialists to approximate this social optimum. We offer four factors that should inform the level and type of error tolerance sought in middle stages of clinical development.

First, clinical equipoise in confirmatory trials establishes upper and lower boundaries for predictivity in phase 2 studies. Though the precise placement of these moral boundaries is hotly debated, we suggest that as a general rule, when the frequency of false positives in phase 2 is high (e.g., due to poor surrogate endpoints), greater effort should be invested in early to mid-stage testing before advancing drugs into phase 3 trials; when this frequency is low, researchers can scale back their efforts in phase 2.

Second, the rate of false positives tolerated in phase 2 should be inversely proportionate to the abundance of candidates in the pipeline. Failing to screen truly effective agents, or screening but failing to detect utility has opportunity costs. Where both pipeline abundance and prior odds of finding an active agent are low, the opportunity cost of a false negative will be substantial, and therefore, phase 2 studies should be relatively permissive with respect to false positives.17 Where pipeline abundance is high but prior odds of success low, studies should aim for higher positive predictivity so that resources from preempted confirmatory testing can be redirected toward earlier phases.18 However, if too high a level of positive predictivity is attained and resources from preempted phase 3 studies cannot be rerouted upstream, more resource intensive phase 2 studies will diminish the pool of resources available for screening new candidates, leading to similar opportunity costs.

Third, predictivity must strike a delicate moral balance. We emphasized that the moral justification for exposing subjects to risk in phase 2 studies is different than that for confirmatory studies. A shift towards more predictive studies entails an escalation of burdensome research activities that often cannot be justified on the basis of direct therapeutic benefit.19 As a general rule, we suggest that, where individuals are least able to protect their own interests or endure harms (e.g. pediatric populations, economically deprived populations), researchers should tread cautiously with implementing study designs that increase positive predictivity through increases in volunteer burden.

Fourth, the level of positive predictivity sought should be informed by the social utility of decisively negative phase 3 trials. We can envision two circumstances where the social value might be large. The first is when phase 3 trial outcomes enable the research community to update key theories of pharmacology and/or pathophysiology that are guiding drug development. Experiments are always embedded within a framework of theories, and trial results—in addition to testing an agent’s utility—provide grounds for revising those theories.20 Insofar as theories drive development of other drugs, negative phase 3 trials have substantial social utility, because they allow drug developers to reassess priorities. In such circumstances, phase 2 designs should have greater tolerance for false positives. A second circumstance where adequately powered, phase 3 trials are critical is for costly or risky interventions that have been taken up into clinical practice (for example, the off-label use of a drug). In such circumstances, only decisive disconfirmations will be adequate for altering practice—hence there is less of a premium on phase 2 studies that produce fewer false positives.

Conclusion

Decades of basic research have uncovered myriad new targets and therapeutic strategies. Yet in areas with the most pressing health needs—cancer, orphan disease, neurodegenerative diseases, infection prophylaxis—late stage failures are all too common. Patients, drug companies, investigators, and funding agencies have understandably sought designs that produce fewer false positives in initial tests of drug activity.

We have argued that implementation of such designs is not without costs—for both the human subjects and the research system as a whole. The middle stages of development involve distinctive challenges that should not be overlooked in the quest for positive phase 3 trials. Phase 2 trial designs must strike a balance between the imperatives of positive predictivity and those of enabling research systems to process a pipeline of plentiful candidates. We are agnostic as to whether this balance is being appropriately struck in current practice. Nevertheless, those advocating reforms in the way new drugs are initially tested for efficacy should establish whether such changes would bring trials closer to this social optimum. This commentary has sought to provide these advocates—along with economists, policy-makers, epidemiologists, and ethicists—considerations for making this assessment.

Figure 1.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (EOG 102824).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Spencer Phillips Hey, Biomedical Ethics Unit/Department of Social Studies of Medicine/McGill University, 3647 Peel Street, Montreal, QC H3A 1X1, Ph: (514) 559-5996.

Jonathan Kimmelman, Biomedical Ethics Unit/Department of Social Studies of Medicine/McGill University, 3647 Peel Street, Montreal, QC H3A 1X1, Ph: (514) 398-3306.

References

- 1.Roberts TG, Lynch TJ, Chabner BA. The phase iii trial in the era of targeted therapy: Unraveling the “go or no go” decision. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3683–3695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kola I, Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:711–715. doi: 10.1038/nrd1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zia MI, Siu LL, Pond GR, Chen EX. Comparison of outcomes of phase ii studies and subsequent randomized control studies using identical chemotherapeutic regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6982–6991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benowitz S. Newer phase ii trial designs gaining ground. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1428–1429. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusuf S. Challenges in the conduct and interpretation of phase ii (pilot) randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2000;139:S136–142. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubinstein LV, Korn EL, Freidlin B, Hunsberger S, Ivy SP, Smith MA. Design issues of randomized phase ii trials and a proposal for phase ii screening trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7199–7206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone A, Wheeler C, Barge A. Improving the design of phase ii trials of cytostatic anticancer agents. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma MR, Maitland ML, Ratain MJ. Other paradigms: Better treatments are identified by better trials. Cancer J. 2009;15:426–430. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181b9c5d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauerwein RW, Roestenberg M, Moorthy VS. Experimental human challenge infections can accelerate clinical malaria vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:57–64. doi: 10.1038/nri2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimmelman J, London AJ. Predicting harms and benefits in translational trials: ethics, evidence, and uncertainty. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djulbegovic B, Kumar A, Magazin A, Schroen AT, Soares H, Hozo I, Clarke M, Sargent D, Schell MJ. Optimism bias leads to inconclusive results: An empirical study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:583–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.London AJ, Kimmelman J, Carlisle B. Research ethics. rethinking research ethics: the case of postmarketing trials. Science. 2012;336:544–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1216086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.London AJ, Kimmelman J, Emborg ME. Beyond access vs. protection in trials of innovative therapies. Science. 2010;328:829–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1189369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutson AD, Wilding GE. An examination of the relative impact of type i and type ii error rates in phase ii drug screening queues. Pharm Stat. 2012;11:157–162. doi: 10.1002/pst.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bristol N. Should terminally ill patients have access to phase i drugs? Lancet. 2007;369:815–816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Eschenbach A. Medical innovation: How the u.s. can retain its lead. Wall Street J. 2012 Feb 14; Opinion. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert PB. Some design issues in phase 2b vs phase 3 prevention trials for testing efficacy of products or concepts. Stat Med. 2010;29:1061–1071. doi: 10.1002/sim.3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips PPJ, Gillespie SH, Boeree M, Heinrich N, Aarnoutse R, McHugh T, Pletschette M, Lienhardt C, Hafner R, Mgone C, Zumla A, Nunn AJ, Hoelscher M. Innovative trial designs are practical solutions for improving the treatment of tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:S250–257. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson JA, Kimmelman J. Extending clinical equipoise to phase 1 trials involving patients: Unresolved problems. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2010;20:75–98. doi: 10.1353/ken.0.0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duhem P. La thŭorie physique son objet et sa structure. 2. Chevalier et Rivière; Paris: 1914. [Google Scholar]; Wiener P, translator. The aim and structure of physical theory. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 1954. [Google Scholar]