Abstract

Background

22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) is a common genetic subtype of intellectual disability (ID) remarkable for its constellation of congenital, developmental and later-onset features. Survival to adulthood is now the norm, and serious psychiatric illness is common in adults. However, little is known about the experiences and perceived needs of individuals with 22q11.2DS and their caregivers at time of transition from paediatric to adult models of care and beyond.

Method

We administered a mail survey to 84 caregivers of adults with 22q11.2DS and 34 adult patients themselves, inquiring about medical and social services, perceived burden and major challenges in adulthood in 22q11.2DS. Standard quantitative and qualitative methods were used to analyse the responses.

Results

Fifty-three (63.1%) caregivers and 20 (58.8%) adults with 22q11.2DS completed the survey. Perceived burden was high, with psychiatric illness and/or behavioural issues considered the most challenging aspects of adulthood in 22q11.2DS by the majority of caregivers (70.0%) and many patients themselves (42.9%). Irrespective of the extent of ID and the presence or absence of other major features, caregivers expressed dissatisfaction with medical and social services for adults, including at time of transition from paediatric care.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the subjective experiences of adults with 22q11.2DS and their caregivers and to identify their perceived needs for services. Better awareness of 22q11.2DS and its later-onset manifestations, early diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric illness, additional support at time of transition and dedicated clinics for adults with 22q11.2DS may help to improve patient outcomes and reduce caregiver burden.

Keywords: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, adult, burden, caregivers, intellectual disability, schizophrenia

Background

One of the most common genetic diagnoses in children and adults with intellectual disability (ID) is 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS), a multisystem disorder with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 2000–4000 live births (Goodship et al. 1998; Bassett et al. 2011; McDonald-McGinn & Sullivan 2011). Substantial variability in clinical expression of the associated 22q11.2 microdeletion and limited awareness among clinicians and the general population likely contribute to the under-recognition of 22q11.2DS, particularly in adults (Kapadia & Bassett 2008). Both congenital and developmental features with lifelong consequences (e.g. congenital heart disease; CHD), and later-onset conditions, are common in adulthood in 22q11.2DS and represent major needs for service (Bassett et al. 2005, 2011). Low associated childhood mortality (McDonald-McGinn & Sullivan 2011) and non-zero reproductive fitness (Costain et al. 2011), in combination with increasing indications for genome-wide chromosomal microarray testing (Miller et al. 2010), suggest that the number of diagnosed and undiagnosed adults with 22q11.2DS will continue to grow. Of concern are data that suggest widespread knowledge deficiencies among service providers (Lee et al. 2005) and sub-optimal medical and social service provision (Udwin et al. 1998; Griffith et al. 2011a,b) in the context of such genetic syndromes.

Most adults with 22q11.2DS have an IQ in the borderline to mild ID range, and those with an intellect in the average range typically have learning difficulties (LD) (Bassett et al. 2005; Chow et al. 2006; De Smedt et al. 2007; De Smedt et al. 2009). Neuropsychiatric diseases can further affect cognition and are among the most common later-onset conditions associated with 22q11.2DS; about three in every five adults with the syndrome will develop one or more treatable psychiatric disorders in their lifetime (Fung et al. 2010). There is a particularly elevated risk for schizophrenia and generalised anxiety disorder (Murphy et al. 1999; Bassett et al. 2005; Fung et al. 2010). General reports regarding neuropsychiatric conditions such as ID or schizophrenia in isolation indicate there is a significant associated burden of care (Udwin et al. 1998; Barnhart 2001; Awad & Voruganti 2008; Bianco et al. 2009; Caqueo-Urizar et al. 2009). The subjective quality of life of an adult with ID may also be modulated by the extent of psychiatric and behavioural issues, adaptive functioning and social services provided (Schwartz & Ben-Menachem 1999; Perry & Felce 2003; Schwartz & Rabinovitz 2003), but data are limited.

The specific challenges of living with, or caring for someone with, 22q11.2DS and its multisystem adult manifestations are largely unknown. We surveyed the opinions of 34 adults with 22q11.2DS and 84 principal caregivers about medical and social service provision, perceived burden and challenging features in adulthood for the purpose of addressing this issue. We postulated that perceived burden would be high and largely attributed to neuropsychiatric morbidities. We also anticipated that caregiver and patient comments would provide valuable insights into service needs, with different profiles of need driven by the presence or absence of major associated features.

Method

Participants

Adults (≥18 years) with 22q11.2DS were originally ascertained through congenital cardiac, psychiatric and genetics services using clinical referrals and/or active screening (Fung et al. 2008; Bassett et al. 2010). 22q11.2 deletions were confirmed using standard techniques, for example fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) with a standard probe from the 22q11.2 region (Bassett et al. 2008b). As previously described (Bassett et al. 2009; Costain et al. 2011), for this cohort of adults with 22q11.2DS we have comprehensive medical and psychiatric data derived from semi-structured interviews and review of lifetime medical records. We classified CHD by structural complexity (Billett et al. 2008), and termed tetralogy of Fallot and other major structural defects ‘serious CHD’ (Bassett et al. 2009; Costain et al. 2011). We confirmed Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition; DSM-IV) lifetime diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (collectively termed ‘schizophrenia’), and non-psychotic mood or anxiety disorders (‘depression/ anxiety’), using established methods (Bassett et al. 2003; Fung et al. 2010). We used the American Association of Mental Retardation Classification for mild (IQ 50–75) and severe (IQ < 50) ID (collectively termed ‘ID’), and determined diagnoses from functioning and IQ testing results (Chow et al. 2006; Butcher et al. 2012). Principal caregivers of adults with confirmed 22q11.2 deletions were self-identified at clinic visits and/or by the adults with 22q11.2DS. There were no exclusion criteria with respect to caregivers – i.e. all caregivers were included, regardless of ID or medical or psychiatric state of the respective adults with 22q11.2DS. Our study also included a subset of adult patients who were capable of reading at a grade four level or higher and considered psychiatrically stable by their treating physician. The study was approved by local research ethics boards.

Survey design and distribution

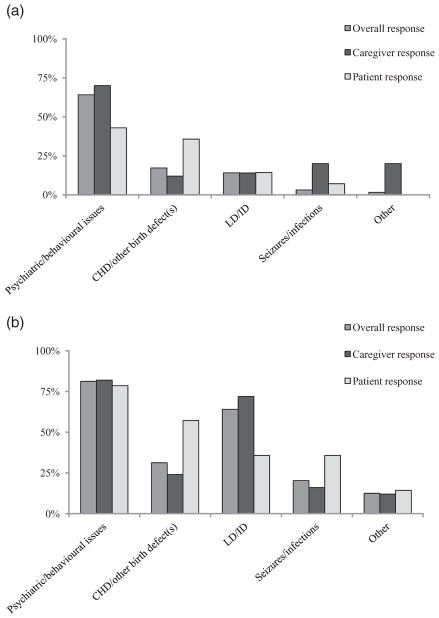

As previously described (Costain et al. 2012), we used a participatory design in developing surveys to assess the opinions of caregivers and adults with 22q11.2DS on a range of issues. Items were created specifically for this population based on the existing literature and clinical experience, and subsequently modified using feedback from pilot testing with a small group of patients, caregivers, lay people and clinicians to optimise accessibility. Individuals with 22q11.2DS were encouraged to ask for assistance as needed to complete the survey. Survey results pertaining to the impact of the molecular diagnosis of the underlying 22q11.2 deletion are presented elsewhere (Costain et al. 2012). Herein we report on the responses to 10 patient-focused five-point (‘Strongly disagree’ to ‘Strongly agree’) Likert scale items, five each relating to: (i) caregiver needs and burden (Fig. 1a), and (ii) satisfaction with medical and social services (Fig. 1b). Adults with 22q11.2DS completed modified versions of the latter five items (Fig. 1c). Respondents were instructed to focus on global provision of services and not on the specialised services offered by our dedicated clinic for adults with 22q11.2DS. Both positive and negative statements were included in approximately equal proportions in order to minimise acquiescence bias (Fig. 1). The wording in Fig. 1 however was modified from the original survey to facilitate interpretation of the results.

Figure 1.

Caregiver burden and perceived service needs in adulthood in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS). The wording of some items was reversed ([R]) in the actual survey and the ‘Neutral’ option was phrased as ‘Neither agree nor disagree’. (a) One hundred per cent stacked bar graphs displaying Likert scale responses to five items concerning caregiver needs and burden. The total number of caregiver responses to items 1 through 5 was 48, 50, 49, 49 and 53 respectively. (b) One hundred per cent stacked bar graphs displaying caregiver Likert scale responses to five items concerning medical and social service provision. The total number of caregiver responses to items 1 through 5 was 47, 43, 47, 49 and 49 respectively. (c) One hundred per cent stacked bar graphs displaying patient Likert scale responses to five items concerning medical and social service provision. The total number of adult responses to items 1 through 5 was 18, 19, 17, 19 and 18 respectively.

Caregivers and patients were also asked to select and rank the three most challenging aspects of adulthood in 22q11.2DS from a list of eight frequently associated features (Bassett et al. 2005, 2011): CHD, other birth defect(s), LD/ID, seizures, infections, schizophrenia, depression/ anxiety and other behavioural/psychiatric issues. We also included options to list other features. In our analysis, we grouped schizophrenia, depression/anxiety and other behavioural/ psychiatric issues as ‘behavioural/psychiatric issues’, and these together with LD/ID as ‘neuropsychiatric issues’.

Definitions and examples of key terms were included in the survey. For example, ‘medical care’ included medical, nursing, dental and other allied health professional services, and examples of ‘social services’ included case management, help with transportation and financial assistance. Comment sections provided an opportunity for respondents to provide a context for their Likert scale responses and to express additional thoughts regarding their experiences with 22q11.2DS. Surveys were distributed by surface mail to caregivers of adults with 22q11.2DS (n = 84) and to a subset of adult patients (n = 34; as above in Participants), accompanied by a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study and a postage-paid, self-addressed envelope (Costain et al. 2012). One reminder letter was sent, and up to two reminder phone calls were made to non-respondents.

Analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using the statistical software Stata 10.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). We applied standard descriptive statistics and statistical tests to the demographic characteristics of survey respondents and non-respondents, and the clinical features of the corresponding adults with 22q11.2DS (Table 1) (Costain et al. 2012). Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare caregiver responses for patients with and without schizophrenia, ID, depression/ anxiety and CHD, respectively, as well as to analyse results regarding challenging problems in adulthood in 22q11.2DS. Exploratory analyses that included further break-down of ID into mild and severe categories showed uninformative results (data not shown), likely because the majority of adults with 22q11.2DS in the study had borderline to mild ID. Prior to our analyses, we elected to collapse the categories ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’ to simply ‘disagree’, and ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ to ‘agree’. All analyses were two-tailed, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical variables pertaining to survey respondents and non-respondents (Costain et al. 2012)

| Caregivers (n = 84) | Adults with 22q11.2DS (n = 34) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Response (n = 53) | No response (n = 31) | Response (n = 20) | No response (n = 14) | |||

|

| ||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | P value* | n (%) | n (%) | P value† | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Female sex | 25 (47.2) | 16 (51.6) | 0.694 | 12 (60.0) | 7 (50.0) | 0.728 |

| Serious CHD | 19 (35.8) | 17 (54.8) | 0.090 | 10 (50.0) | 6 (42.9) | 0.681* |

| Mild to severe ID | 37 (69.8) | 22 (71.0) | 0.911 | 10 (50.0) | 9 (64.3) | 0.495 |

| Schizophrenia | 23 (43.4) | 10 (32.3) | 0.313 | 5 (25.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0.364 |

| Non-psychotic mood/anxiety disorder | 13 (24.5) | 9 (29.0) | 0.651 | 7 (35.0) | 4 (28.6) | 0.999 |

| Living situation | 0.148 | 0.403* | ||||

| With parents or other relatives | 30 (56.6) | 23 (74.2) | – | 14 (70.0) | 12 (85.7) | – |

| Group home or long-term care facility‡ | 12 (22.6) | 7 (22.6) | – | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Independently | 7 (13.2) | 1 (3.2) | – | 4 (20.0) | 2 (14.3) | – |

| Other | 4 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | – | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P value§ | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P value§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-scale IQ | 70.3 (12.7) | 70.7 (11.3) | 0.889 | 76.1 (11.4) | 73.9 (8.6) | 0.549 |

| Age (years) | 33.2 (10.8) | 30.8 (8.4) | 0.430 | 34.8 (11.1) | 36.2 (9.9) | 0.563 |

| Caregiver characteristics | ||||||

| Age of caregiver (years) | 54.7 (10.4) | 55.7 (6.4) | 0.951 | – | – | – |

Pearson’s chi-square test.

Fisher’s exact test unless otherwise stated.

Also includes apartment with support and hospital.

Mann–Whitney U-test.

22q11.2DS, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome; CHD, congenital heart defect; ID, intellectual disability; SD, standard deviation; IQ, intelligence quotient.

Initial qualitative content analysis of caregiver and adult patient comments was conducted as a paid service by an independent company (van Amsterdam Education and Research Inc.), blind to the identity of the respondents and the corresponding quantitative data. Comments were systematically coded by hand and then evaluated using QSR NVivo9 software (Gibbs 2009) to identify key themes (Costain et al. 2012). The authors subsequently re-examined the data within the appropriate clinical context and isolated themes related to service needs and overall burden of care. Representative quotations for each theme are included in Table 2, and are all from different respondents.

Table 2.

Recurring themes in the caregiver and patient comments regarding adulthood in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS)

| Themes | Comments |

|---|---|

| Caregiver themes | Representative caregiver comments |

|

| |

| Insufficient knowledge regarding adult-onset (especially neuropsychiatric) conditions | |

|

‘I was unprepared for the schizophrenia side of things.’ ‘The more information, the better our son’s life will be. We worry about his future. What to expect?… [We] just want our son to be happy. The more information available will help us help him.’ |

| Lack of access to adequate social services | |

|

‘[Professional] Caregivers have been uncompassionate and uncaring when faced with challenging behaviours. A huge lack of training; she [the patient] got worse.’ ‘Co-ordination between services is non-existent. In general care-managers have been disappointing, particularly in the area of matching needs to programs.’ |

| Issues related to ageing | |

|

‘I worry that my son will fall through the cracks when I am unable to look after him.’ ‘If our health fails, we’re through. Largest anxiety lies in what will happen when we die.’ |

| Problems related to caring for an adult (cf. a child) | |

|

‘It’s very hard when they’re this age and still can’t manage to take care of themselves.’ ‘It is much more difficult to advocate for an adult than a child. Doctors, social workers, teachers etc. want the adult to ask/explain things themselves which can be next to impossible for adults with learning disabilities or with anxiety issues.’ |

| Perceived burden on themselves and their families | |

|

‘Families fall apart under the severity of this illness. You don’t know what you’re dealing with or how to help – or where to go. It is terrible.’ ‘The family provides much support that is at times beyond what we can bear. The added stress that this places on everyone makes life very difficult and strains familial relationships.’ |

|

| |

| Patient themes | Representative patient comments |

|

| |

| Desire to better understand 22q11.2DS | |

|

‘I would really like to have a better, or rather concrete understanding of how this syndrome is caused…. I understand that I brought the gene down to my son, but am confused as to how I obtained this 22q deletion as no one in my family has it.’ ‘I personally think that as an adult with 22q that I may not know enough.’ |

| Need for greater knowledge of, and access to, social and employment services | |

|

‘I have a lot of help from my parents and my sisters but I’m not aware of any help outside the home. Is there a way to have less of a struggle in the work world?’ ‘I am unsure about the social/medical services available as I only recently found out I have 22q. (Perhaps more education about the syndrome would help.)’ |

Results

Participant characteristics

Seventy-three participants (61.9%) completed and returned the survey: 53 caregivers (63.1%) and 20 adults with 22q11.2DS (58.8%) (Costain et al. 2012). Responses concerned a total of 60 unrelated individuals with 22q11.2DS. Overall, there were no significant differences between respondents and non-respondents (Table 1). The majority of caregiver respondents were mothers (n = 36, 67.9%); fathers (n = 2, 3.8%), siblings (n = 4, 7.5%), other relatives (n = 3, 5.7%), healthcare workers (n = 4, 7.5%) and home support workers (n = 4, 7.5%) accounted for the remaining caregivers.

Quantitative results

Caregiver needs and burden

The majority of caregivers reported feeling more responsible that they should be for managing the adult’s care (n = 29, 58.0%), needing to advocate for required services (n = 30, 61.2%), and initially being unprepared to care for an adult with 22q11.2DS (n = 32, 65.3%) (Fig. 1a). No significant differences were noted for any of the five burden-related items by any individual major associated feature of the corresponding patient (e.g. ID; data not shown).

Satisfaction with medical and social services

Substantial proportions of caregivers reported dissatisfaction with current medical (n = 22, 44.9%) and social services (n = 31, 63.3%), and with service provision at the time of transition from paediatric to adult care (n = 28, 59.6%) (Fig. 1b). A significantly greater proportion of caregivers of patients with serious CHD (n = 11/18, 61.1%), compared with those without CHD (n = 5/29, 17.2%; χ2 = 9.91, d.f. = 2, P = 0.007), reported that medical services were better in childhood than in adulthood. Further, compared with caregivers of adults with schizophrenia (n = 2/20, 10.0%), a greater proportion of caregivers of adults without schizophrenia (n = 14/27, 51.9%; χ2 = 9.64, d.f. = 2, P = 0.008) indicated that medical services were better in childhood. There were no other significant differences noted in caregiver responses regarding medical and social services by presence or absence of major associated feature of 22q11.2DS (data not shown). Overall, a considerable proportion of the adults with 22q11.2DS surveyed were satisfied with their current medical (n = 11, 57.9%) and social (n = 8, 44.4%) services (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, a substantial minority did not agree that medical (33.3%) and social (42.1%) services had been better in childhood (Fig. 1c).

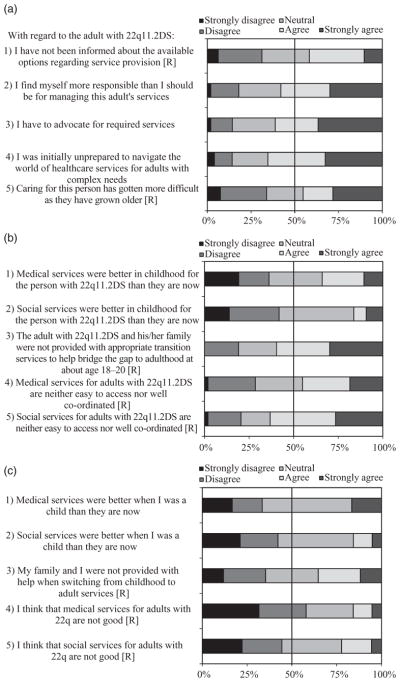

Major difficulties in adulthood

Fifty (94.3%) caregivers and 14 (70.0%) patients correctly completed this section of the survey, ranking health and related problems according to difficulty (Fig. 2a,b). Both groups most frequently endorsed problems related to behaviour, psychiatric illness or ID, but patients were non-significantly more likely to also or instead emphasise problems that were physical in nature [e.g. CHD/other birth defect(s); χ2 = 6.04, d.f. = 4, P = 0.196]. LD/ID was frequently seen as a major challenge in adulthood in 22q11.2DS (Fig. 2b) but not as the most challenging feature (Fig. 2a). The remaining three caregivers and six patients selectively endorsed, but did not rank, difficulties in a manner consistent with the overall results.

Figure 2.

Major adult challenges perceived by caregivers and individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Bar graphs displaying overall, and caregiver and patient subgroup, ranked responses to the question: ‘Which health and related problems have been most difficult for you (to manage) since you (he/she) turned 18?’ (a) Top ranked problem only. (b) Top three ranked problems. The ‘Other’ group included employment issues (a, b), and diabetes, memory problems, parkinsonism/ tremor and incontinence (b). Abbreviations are used for serious congenital heart disease (CHD), learning difficulties (LD) and intellectual disability (ID).

There was also a non-significant trend towards a difference between the responses of caregivers of patients with and without schizophrenia (χ2 = 9.42, d.f. = 4, P = 0.052), with more caregivers in the latter group labelling CHD or LD/ID as the most challenging problem. All 22 caregivers of adults with schizophrenia reported the chief difficulty as psychiatric/behavioural issues (n = 20, 90.9%) or LD/ID (n = 2, 9.1%). Nonetheless, even among caregivers of patients without schizophrenia, psychiatric/behavioural problems were reported to be the most frequent source of difficulty (15/28, 53.6%).

Qualitative results

Thirty-six (67.9%) of the caregivers [n = 32 (88.9%) female; n = 29 (80.6%) mothers] provided handwritten comments, from which five main recurring and overlapping themes emerged relevant to this report (Table 2). In addition to commenting directly on survey items (e.g. access to social services), caregivers elected to describe both the personal and family challenges associated with caring for an adult with 22q11.2DS and select positive experiences. Many caregivers reported feeling overwhelmed by their roles as advocate, educator and co-ordinator of services, and described being ‘stressed’ and ‘frustrated’. Several acknowledged that caring for an adult with complex problems takes a toll on the entire family, and expressed a need for additional help and support. Mothers often described their fears for the future, including the uncertainty surrounding the trajectory of the adult’s illness and how the family will cope with emerging problems. Some respondents worried about how their increasing age will affect the care they are able to provide to the individual with 22q11.2DS.

Eleven (55.0%) of the patients [n = 9 (81.8%) female] also provided substantive comments. Major patient themes were similar, but tended not to include more abstract concepts such as concerns about the future (Table 2). Comments revealed a group of individuals who were cognisant of their condition and its relative rarity, but felt limited by their lack of knowledge regarding the syndrome and the paucity of support services and resources available to optimise their day-to-day functioning. Many of the adult respondents felt that service providers need to know more about 22q11.2DS.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine perceived burden and related issues in adulthood in 22q11.2DS. As predicted, the subjective burden of illness was high and primarily mediated by the severity of the neuropsychiatric manifestations. Caregiver and adult patient responses provided valuable insights into the diverse service needs of this population, which sometimes varied by the presence or absence of major associated features. These unique perspectives may help to inform new initiatives to improve the quality of life of adults with 22q11.2DS and their caregivers.

Key needs for service

The stated needs of caregivers of adults with 22q11.2DS were broadly consistent with those associated with individual neuropsychiatric conditions in isolation (Freedman & Boyer 2000; Yeh et al. 2008; Caqueo-Urizar et al. 2009). Similarly, our documentation of dissatisfaction with existing medical and social services, including a lack of continuity and co-ordination, is consistent with previous reports involving other genetic disorders, including cri du chat, Angelman, Cornelia de Lange and Williams syndromes (Udwin et al. 1998; Griffith et al. 2011a,b). The constellation of morbidities affecting adults with 22q11.2DS (Bassett et al. 2005, 2011), including widespread cognitive and functional limitations (Chow et al. 2006; De Smedt et al. 2007; De Smedt et al. 2009; Butcher et al. 2012), often necessitated a caregiver advocating on their behalf. As for ID more generally (Bianco et al. 2009), our data suggest that caregivers frequently felt unprepared for the job of advocating for an adult with complex needs and sometimes challenging behaviours.

More caregiver education regarding 22q11.2DS, particularly during adulthood, was requested to facilitate the informing of support workers, service providers and diverse other healthcare professionals about 22q11.2DS. The necessity of adopting an ‘educator’ role may distinguish this syndrome from many other conditions associated with psychiatric illness or ID, such as Down syndrome, that are relatively better recognised and understood (Freedman & Boyer 2000; Yeh et al. 2008; Caqueo-Urizar et al. 2009). Improved public and healthcare professional education about 22q11.2DS (Lee et al. 2005; Kapadia & Bassett 2008), and formal organisations and/or societies dedicated to providing a concerted voice on behalf of this population, may facilitate acquisition and retention of needed services.

Receiving a genetic/aetiological diagnosis has the potential to lead to improvements in services (Minnes & Steiner 2009; Costain et al. 2012), but many challenges in accessing assistance remain (Minnes & Steiner 2009; Hallberg et al. 2010). For congenital features like serious CHD, the results suggest that the adult services for these chronic conditions are less satisfactory than those offered in a paediatric context. We did not observe a significant difference by ID status in the proportion agreeing with the statement suggesting social services were superior in childhood (53.9% with ID vs. 36.7% without ID; χ2 = 1.53, d.f. = 2, P = 0.464). Nonetheless, the direction of the trend was consistent with several studies involving the general ID population (Bianco et al. 2009; Ryan 2010). These results provide further evidence that specialised paediatric services for individuals with genetic conditions may be unsuitable for adults who present with different health priorities (Taylor et al. 2006).

Documentation of patient perspectives in conditions associated with ID is informative but rare. The expressed desire of the adults with 22q11.2DS surveyed to learn more about their condition provides an additional impetus for periodic genetic counselling (Bassett et al. 2011), even in the absence of a reproductive imperative (Costain et al. 2011). The patient respondents also appeared to be relatively more satisfied with their medical and social services than did caregivers, although a direct comparison of responses between groups was not possible. A future study could investigate this apparent discrepancy further. We note that the subgroup of adult patients surveyed was purposely selected to maximise the likelihood of comprehension and response, and may not be representative of the overall population of adults with 22q11.2DS.

Transition services

Our results showing dissatisfaction with services when transitioning from paediatric to adult care, and the identified challenges specific to adulthood in 22q11.2DS, reinforce the importance of syndrome-specific transition services (Schrander-Stumpel et al. 2007; Ryan 2010). Multidisciplinary care in childhood is often co-ordinated by paediatricians (Schrander-Stumpel et al. 2007) and increasingly for 22q11.2DS may be facilitated by clinics specialising in this complex syndrome (Bassett et al. 2011). The substantial burden of chronic multisystem disease, frequency and severity of new onset psychiatric and other conditions, need for genetic and reproductive counselling, and often minimal training in genetics and genomics of adult-focused healthcare professionals, however, may present significant barriers to providing appropriate services at time of transition (Taylor et al. 2006; Schrander-Stumpel et al. 2007; Ryan 2010; Bassett et al. 2011; Costain et al. 2011). Most infants with 22q11.2DS now survive to adulthood and beyond (Bassett et al. 2009; McDonald-McGinn & Sullivan 2011), and clinical and family expectations of a smooth transition from childhood to adult care will likely continue to grow (Schrander-Stumpel et al. 2007; Bassett et al. 2011). Understanding the specific and general needs at this critical juncture will facilitate the future design of appropriate protocols and services.

Major difficulties in adulthood

As predicted, our findings suggest that psychiatric and behavioural issues are often perceived as the most challenging aspects of adulthood in 22q11.2DS by both caregivers and adult patients themselves. These conditions are most likely to bring adults with 22q11.2DS to medical attention and to affect functioning, which in turn may complicate other aspects of management (Chow et al. 2006; Butcher et al. 2012). Early diagnosis and treatment can have a substantial impact on course and outcome (Bassett et al. 2008a), emphasising the importance to the ID community of recognising 22q11.2DS and appreciating the increased risk for treatable psychiatric illnesses. A periodic neuropsychiatric evaluation is the standard of care (Bassett et al. 2011), and could be coupled with the provision of information to, and implementation of individualised support plans for, patients and their caregivers. Family interventions for conditions like schizophrenia in isolation (Awad & Voruganti 2008), which often include coping mechanisms for caregivers, have been shown to improve the family environment, and could inform the design of similar interventions to reduce caregiver burden in 22q11.2DS.

Caregiver comments regarding the extent of impairment in adaptive functioning highlight the unique challenges faced by adults with 22q11.2DS (Butcher et al. 2012). These are distinct from those affecting children with 22q11.2DS, as adulthood increases expectations of the individual and encourages autonomy. Low awareness among the public, and even the ID community, may further increase expectations as individuals with 22q11.2DS can have minimal dysmorphic features and reasonable expressive language skills that may belie impaired social judgement. A balance must be reached between providing sufficient protection to this potentially vulnerable group, and facilitating optimal functioning and independence, always with consideration of each individual’s situation (Butcher et al. 2012).

Advantages and limitations

This is the first needs assessment and study of caregiver burden in the context of adults with 22q11.2DS, and is unique for the inclusion of patient perspectives. The broad and inclusive sampling, high response rate, and convergence of quantitative and qualitative results increase confidence in our interpretation of the primary findings. We were also sufficiently powered to undertake important subgroup analyses by certain major associated features. Several limitations of the methodological approach are described elsewhere (Costain et al. 2012). Notably, the patients’ responses must be considered in the context of their cognitive limitations, as it was not always possible to gauge the extent of understanding (or misunderstanding) of survey items (Schrander-Stumpel et al. 2007). A future study employing methods better suited for this patient population (e.g. one-on-one interviewing) could now be guided by the key themes identified in this report (Table 2).

As in all studies of this kind, common forms of survey error and cognitive bias (e.g. recall biases pertaining to the extent of satisfaction with paediatric care) can have an impact on individual item responses. Today, transition services for an adolescent with 22q11.2DS may be markedly better than those provided in previous decades to the cohort surveyed. On the other hand, many of the caregivers and patients in this study had access to a nascent clinic for adults with 22q11.2DS, suggesting that those without such resources may face even greater challenges. Lastly, there remains a need for more rigorous methodology with comprehensive measures of global quality of life (Cohen & Biesecker 2010; Townsend-White et al. 2012), which will also allow for comparisons across different populations with ID. We elected not to use such scales in this exploratory study because of concerns that their inclusion might decrease the accessibility of the survey.

Conclusions

This data-driven documentation of major challenges faced by adults with 22q11.2DS and their caregivers has important consequences with respect to improving the functional, social and health outcomes of individuals and families living with this common cause of ID. Our findings highlight important and actionable gaps in care, and may help to inform the future design of suitable interventions to reduce caregiver and patient burden in 22q11.2DS. Improved awareness of the risk for, and earlier diagnosis and effective treatment of, psychiatric illness is essential. Increasing adult-focused healthcare professional awareness and training about 22q11.2DS and its neuropsychiatric and other manifestations, especially in the ID community, could result in improved management of the syndrome in adults (Bassett et al. 2005; Costain et al. 2012).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the adults with 22q11.2DS and their caregivers for sharing their experiences. The authors thank Savithiri Ratnapalan and Ivan Silver for their expertise in survey methodology, Sean Bekeschus for aesthetic design of the survey, Danielle Baribeau for helping to distribute the surveys, Denise van Amsterdam (van Amsterdam Education and Research Inc.) for assistance with the initial qualitative analyses, and Gladys Wong and Monica Torsan for assistance with preparing the manuscript. This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research grants (MOP-97800 and MOP-89066), a Comprehensive Research Experience for Medical Students Summer Studentship (DJK), a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship (GC) and a Canada Research Chair in Schizophrenia Genetics and Genomic Disorders (ASB).

References

- Awad AG, Voruganti LN. The burden of schizophrenia on caregivers: a review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:149–62. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart RC. Aging adult children with developmental disabilities and their families: challenges for occupational therapists and physical therapists. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2001;21:69–81. doi: 10.1300/j006v21n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Chow EW, Abdelmalik P, Gheorghiu M, Husted J, Weksberg R. The schizophrenia phenotype in 22q11 deletion syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1580–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Chow EW, Husted J, Weksberg R, Caluseriu O, Webb GD, et al. Clinical features of 78 adults with 22q11 Deletion Syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2005;138:307–13. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Chow EWC, Hodgkinson KA. Genetics of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. In: Smoller JW, Sheidley BR, Tsuang MT, editors. Psychiatric Genetics: Applications in Clinical Practice. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, DC: 2008a. pp. 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Marshall CR, Lionel AC, Chow EW, Scherer SW. Copy number variations and risk for schizophrenia in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008b;17:4045–53. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Chow EW, Husted J, Hodgkinson KA, Oechslin E, Harris L, et al. Premature death in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2009;46:324–30. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.063800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Costain G, Fung WLA, Russell KJ, Pierce L, Kapadia R, et al. Clinically detectable copy number variations in a Canadian catchment population of schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010;44:1005–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, McDonald-Mcginn DM, Devriendt K, Digilio MC, Goldenberg P, Habel A, et al. Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;159:332–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco M, Garrison-Wade DF, Tobin R, Lehmann JP. Parents’ perceptions of postschool years for young adults with developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2009;47:186–96. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-47.3.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billett J, Cowie MR, Gatzoulis MA, Vonder Muhll IF, Majeed A. Comorbidity, healthcare utilisation and process of care measures in patients with congenital heart disease in the UK: cross-sectional, population-based study with case–control analysis. Heart. 2008;94:1194–9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.122671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher NJ, Chow EWC, Costain G, Karas D, Ho A, Bassett AS. Functional outcomes of adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Genetics in Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caqueo-Urizar A, Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Miranda-Castillo C. Quality of life in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: a literature review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009;7:84. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow EWC, Watson M, Young DA, Bassett AS. Neurocognitive profile in 22q11 deletion syndrome and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;87:270–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JS, Biesecker BB. Quality of life in rare genetic conditions: a systematic review of the literature. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2010;152A:1136–56. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costain G, Chow EWC, Silversides CK, Bassett AS. Sex differences in reproductive fitness contribute to preferential maternal transmission of 22q11.2 deletions. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2011;48:819–24. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costain G, Chow EW, Ray PN, Bassett AS. Caregiver and adult patient perspectives on the importance of a diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2012;56:641–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt B, Devriendt K, Fryns JP, Vogels A, Gewillig M, Swillen A. Intellectual abilities in a large sample of children with Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome: an update. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2007;51:666–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt B, Swillen A, Verschaffel L, Ghesquiere P. Mathematical learning disabilities in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a review. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2009;15:4–10. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman RI, Boyer NC. The power to choose: supports for families caring for individuals with developmental disabilities. Health and SocialWork. 2000;25:59–68. doi: 10.1093/hsw/25.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung WL, Chow EW, Webb GD, Gatzoulis MA, Bassett AS. Extracardiac features predicting 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in adult congenital heart disease. International Journal of Cardiology. 2008;131:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.08.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung WLA, McEvilly R, Fong J, Silversides C, Chow E, Bassett A. Elevated prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:998. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs G. Analysing Qualitative Data. Sage; London: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Goodship J, Cross I, Liling J, Wren C. A population study of chromosome 22q11 deletions in infancy. Archives of Diseases in Childhood. 1998;79:348–51. doi: 10.1136/adc.79.4.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith GM, Hastings RP, Nash S, Petalas M, Oliver C, Howlin P, et al. ‘You have to sit and explain it all, and explain yourself.’ Mothers’ experiences of support services for their offspring with a rare genetic intellectual disability syndrome. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2011a;20:165–77. doi: 10.1007/s10897-010-9339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith GM, Hastings RP, Oliver C, Howlin P, Moss J, Petty J, et al. Psychological well-being in parents of children with Angelman, Cornelia de Lange and Cri du Chat syndromes. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2011b;55:397–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg U, Oskarsdottir S, Klingberg G. 22q11 deletion syndrome – the meaning of a diagnosis. A qualitative study on parental perspectives. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2010;36:719–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia RK, Bassett AS. Recognizing a common genetic syndrome: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008;178:391–3. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH, Blasey CM, Dyer-Friedman J, Glaser B, Reiss AL, Eliez S. From research to practice: teacher and pediatrician awareness of phenotypic traits in neurogenetic syndromes. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2005;110:100–6. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110<100:FRTPTA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome) Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;90:1–18. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182060469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, Biesecker LG, Brothman AR, Carter NP, et al. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2010;86:749–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnes P, Steiner K. Parent views on enhancing the quality of health care for their children with fragile X syndrome, autism or Down syndrome. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2009;35:250–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KC, Jones LA, Owen MJ. High rates of schizophrenia in adults with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:940–5. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J, Felce D. Quality of life outcomes for people with intellectual disabilities living in staffed community housing services: a stratified random sample of statutory, voluntary and private agency provision. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2003;16:11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S. The adolescent and young adult with Klinefelter syndrome: ensuring successful transitions to adulthood. Pediatric Endocrinology Reviews. 2010;8 (Suppl 1):169–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrander-Stumpel CT, Sinnema M, van den Hout L, Maaskant MA, van Schrojenstein Lantman-De Valk HM, Wagemans A, et al. Healthcare transition in persons with intellectual disabilities: general issues, the Maastricht model, and Prader-Willi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2007;145C:241–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C, Ben-Menachem Y. Assessing quality of life among adults with mental retardation living in various settings. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 1999;22:123–30. doi: 10.1097/00004356-199906000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C, Rabinovitz S. Life satisfaction of people with intellectual disability living in community residences: perceptions of the residents, their parents and staff members. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47:75–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MR, Edwards JG, Ku L. Lost in transition: challenges in the expanding field of adult genetics. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2006;142C:294–303. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend-White C, Pham AN, Vassos MV. Review: a systematic review of quality of life measures for people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviours. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2012;56:270–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udwin O, Howlin P, Davies M, Mannion E. Community care for adults with Williams syndrome: how families cope and the availability of support networks. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1998;42 (Pt 3):238–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh LL, Hwu HG, Chen CH, Chen CH, Wu AC. Factors related to perceived needs of primary caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2008;107:644–52. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]