Vibrio cholerae is a diarrheal pathogen and a natural inhabitant of fresh- and saltwater environments. Seasonal outbreaks in areas of endemicity that can develop into worldwide pandemics are linked to the persistence of V. cholerae in aquatic ecosystems, providing a reservoir for the initiation of new cholera epidemics via human ingestion of contaminated food or water (7). Biofilm formation is dependent on the production of an exopolysaccharide (EPS) (13, 17), and the previous finding by the Klose laboratory that a flagellum-dependent pathway induces EPS expression (14) has led to their surprising discovery reported in this issue: the sodium-driven flagellar motor is intimately involved in EPS expression, biofilm formation, and the virulence of V. cholerae (6). The EPS signaling cascade appears to operate through a flagellar motor-based mechanosensor mechanism (5, 6) adapted by bacteria to induce appropriate behaviors on solid surfaces and perhaps additional behaviors in the diverse microenvironments encountered during their life cycle.

THE MATURE BIOFILM: A CITY BY THE BAY

Biofilms have been described as a specialized microbial community whose genesis embodies three distinct stages of development: (i) a free-swimming (termed planktonic) stage, (ii) a transient monolayer stage comprised of an association of single cells that become immobilized on a solid surface, and (iii) mature biofilm, a highly organized, three-dimensional cellular network that may facilitate nutrient availability to certain members of its population (12) and promote resistance to environmental stresses present in aquatic environments (13, 17). In the free-swimming state, flagella and fimbriae are necessary for motility and initial adherence to a solid surface. However, their synthesis is inhibited in biofilms (10, 15), as such appendages may impede the maintenance of biofilm structure by breaking or inhibiting other surface associations required for communal stability (9). In contrast, the synthesis of an EPS is a prerequisite for biofilms and is believed to occur principally after attachment to solid surfaces and microcolony formation. Thus, maturation from the planktonic state to the biofilm state requires a developmental alteration in flagellar, fimbrial, and EPS synthesis, promoting the resultant three-dimensional architecture of mature biofilms.

THERE IS MORE THAN ONE WAY TO BUILD A BIOFILM

At least three distinct signaling pathways are known for EPS production in V. cholerae. Each may operate via discrete signals and/or microenvironments, including (i) a quorum-sensing pathway, wherein the absence of the transcriptional regulator HapR results in enhanced EPS synthesis and biofilm formation (2, 4, 11, 18); (ii) a flagellum-dependent pathway wherein nonflagellated cells induce the expression of EPS synthesis and biofilm formation (6, 14); and (iii) a phase variation pathway that yields two distinct morphological variants termed smooth and rugose (wrinkled). Rugose variants are associated with an enhanced capacity to produce EPS (16, 17).

EPS synthesis is encoded by the Vibrio polysaccharide (vps) genes (17). vps expression can be modulated through the quorum-sensing signaling cascade via the LuxR homologue, HapR, which represses vps expression and virulence factor formation (2, 11, 18). Therefore, hapR mutants are rugose (4), leading to thicker biofilms and enhanced production of virulence factors (e.g., cholera toxin) (8, 19). The biological consequence of quorum-sensing regulation of vps expression is that high cell density appears to promote the cessation of biofilms, perhaps reflecting an upper limit on the number of resident organisms due to spatial constraints within the mature biofilm.

In contrast to the quorum-sensing pathway, the flagellum-dependent pathway of EPS synthesis shows an inverse relationship between EPS expression and virulence factor production, as nonflagellated cells are rugose, producing high levels of EPS that are associated with low levels of cholera toxin and infectivity (6). Moreover, genetic analysis indicates that high-level EPS production, rather than the loss of flagella, is responsible for the virulence attenuation in nonflagellated cells. Last, the control of vps expression and biofilm formation by the flagellum- and phase variation-dependent pathways are linked by the action of transcriptional response regulators, VpsR and VpsT (1, 6, 16), which activate their own as well as each other's expression (1). Maintaining multiple, overlapping signaling pathways for EPS synthesis and biofilm formation may contribute to persistence in the dynamic aquatic environments that occur between seasonal cholera outbreaks.

In addition to bestowing upon bacteria the flexibility to persist in varied microenvironments, the maintenance of multiple EPS signaling pathways allows the opportunity for distinct strains to be selected in which the expression of certain pathways are favored or operational depending on the specific environmental history of the pathogen. This leads to the following question: are V. cholerae strains genetically competent to utilize the three EPS signaling pathways, or have genetic variants that are adapted to specific environmental challenges arisen? The answer appears to be a combination of these genetic possibilities, as some V. cholerae strains utilize both the HapR- and flagellum-dependent pathways, whereas other strains favor one pathway over the other (6); yet other strains fail to utilize either (e.g., spontaneous phase variants appear to arise via a HapR- and flagellum-independent mechanism) (3, 6, 16). Thus, strains collected from clinically and environmentally relevant sources are heterogeneous with regard to their ability to signal EPS synthesis and biofilm formation and may reflect the specific microenvironments encountered by given strains during their life cycle. Does EPS signaling-based heterogeneity also occur within the population of cells that comprise the microenvironments within a single biofilm, and if so, does such heterogeneity contribute to the formation and/or maintenance of the three-dimensional biofilm architecture? The answers to these questions remain unclear.

TO SWIM OR NOT TO SWIM: IS THAT THE QUESTION?

The signaling mechanisms that transduce the varied environmental inputs into altered bacterial behavior (e.g., planktonic to biofilm formation) remain a mystery. However, recent work by the Klose laboratory (6) has shed light on this important question for at least the flagellum-dependent EPS signaling pathway, and it appears to involve, in part, the mechanosensing of flagellar rotation.

As mentioned above, V. cholerae nonflagellated (flaA) mutants are rugose and are associated with elevated levels of EPS production and biofilm formation (14). The initial favored hypothesis for these observations was that the lack of a complete flagellum was responsible for the elevated levels of EPS expression and the rugose phenotype. This hypothesis has been refined further since mutations in the sodium-driven flagellar motor genes (e.g., motX), alone and in combination with fla mutations (motX fla), result in low levels of vps transcription and biofilm formation as well as a smooth colony phenotype (6). This suggests that the flagellar motor, rather than the lack of motility or flagella, participates in the transduction of the EPS-inducing signal in addition to functioning in flagellar rotation. Further, it appears that the flagellar motor dependence is functional rather than structural, as the addition of phenamil, a specific sodium motor poison, resulted in reduced vps transcription and biofilm formation in wild-type and in nonflagellated cells (6). An alternative explanation for these data is that phenamil disrupts the sodium influx through the motor channel, which may have structural implications for the signaling mechanism. However, this does not affect the conceptual interpretation that the EPS-inducing signal is transduced through the flagellar motor, perhaps via mechanosensing of flagellar rotation, wherein a reduction in flagellar rotation may signal high levels of EPS synthesis and biofilm formation (6). Consistent with this hypothesis, it has recently been reported that the progression from the planktonic stage to the monolayer stage may occur with the concomitant appearance of a subpopulation of either nonflagellated (wild-type) cells or cells that lack an active flagellum (9). The selection for nonflagellated cells during the transition to the monolayer stage could occur because active flagella may break or hinder permanent attachment and immobilization of the organisms to a solid surface by alternate adhesins (9).

Mechanosensing of flagellar rotation through a sodium-driven flagellar motor has been proposed previously for the induction of lateral flagellar transcription in Vibrio parahaemolyticus (5). Thus, the function of the flagellar motor as a mechanosensor of flagellar rotation may be shared among Vibrio spp. and perhaps selected to facilitate bacterial growth on solid surfaces (6). This raises the possibility that the proposed mechanosensor mechanism has been co-opted as a general bacterial mechanism to induce appropriate behaviors in a wide range of microenvironments.

How does a membrane-associated organelle (the flagellar motor) sense the presence or absence of an extracellular appendage (the flagellum) and transduce that information to an intracellular signaling cascade resulting in EPS synthesis? This question was solved in part by showing that activation of the vps genes through the transcriptional activator, VpsR, required the presence of MotX, suggesting that MotX was epistatic to VpsR in the EPS signaling pathway (6). As expected, constitutive activation of VpsR precluded the dependence of EPS signaling through the flagellar motor (6). However, a direct interaction between the transcriptional activator, VspR or VspT, and the vps structural genes has not been demonstrated (1, 6). Curiously, both VspR and VspT are homologous to response regulators of two-component regulatory systems that are typically associated with sensory histidine kinases, yet no cognate sensor kinases have been identified (1, 6). Future studies regarding the environmental signals and regulatory functions that govern EPS signaling will be central to understanding the molecular basis of bacterial adaptation and persistence.

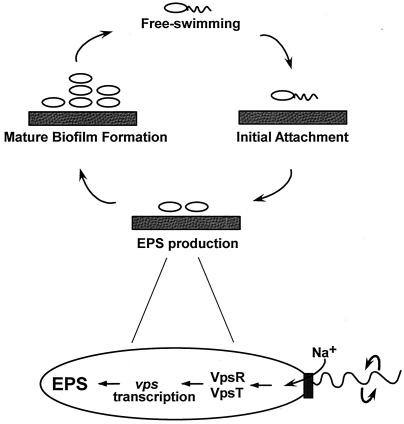

The presence of multiple EPS signaling pathways that function in discrete microenvironments confers upon V. cholerae the unique ability to persist in aquatic reservoirs during the long periods between seasonal outbreaks in areas of endemicity. Such persistence may be driven by a sodium flagellar motor-based mechanosensor mechanism through which a reduction in flagellar rotation leads to EPS synthesis and biofilm formation via the VpsR/VpsT signaling cascade (Fig. 1). Once conditions become unfavorable for maintenance of the mature biofilm, flagellar rotation can be restored, allowing escape; the free-swimming pathogen can relocate and initiate a nascent biofilm and/or manifest itself as the source of a new cholera outbreak.

FIG. 1.

V. cholerae EPS production and biofilm formation. Adherence of free-swimming bacteria to a solid surface results in EPS production and resultant mature biofilm formation, allowing bacterial persistence during the prolonged periods between seasonal cholera outbreaks. By restoration of flagellar function, free-swimming bacteria can escape from the biofilm and initiate infections by human ingestion of contaminated food or water. In the model for EPS production shown here, the sodium-driven flagellar motor (vertical rectangle) mechanically senses a reduction in flagellar rotation and/or sodium influx, signaling the activation of VpsR and VpsT. These transcriptional regulators induce vps transcription and EPS production, required for the development of a mature biofilm.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Foundation and UC Biotech grants (2001-15 and 2002-14) to (M.J.M.).

The views expressed in this Commentary do not necessarily reflect the views of the journal or of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Casper-Lindley, C., and F. H. Yildiz. 2004. VpsT is a transcriptional regulator required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and the development of rugose colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 186:1574-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer, B. K., and B. L. Bassler. 2003. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 50:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, and O. White. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jobling, M. G., and R. K. Holmes. 1997. Characterization of hapR, a positive regulator of the Vibrio cholerae HA/protease gene hap, and its identification as a functional homologue of the Vibrio harveyi luxR gene. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1023-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawagishi, I., M. Imagawa, Y. Imae, L. McCarter, and M. Homma. 1996. The sodium-driven polar flagellar motor of marine Vibrio as the mechanosensor that regulates lateral flagellar expression. Mol. Microbiol. 20:693-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauriano, C. M., C. Ghosh, N. E. Correa, and K. E. Klose. 2004. The sodium-driven flagellar motor controls exopolysaccharide expression in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 186:4864-4874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Lipp, E. K., A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 2002. Effects of global climate on infectious disease: the cholera model. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:757-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller, M. B., K. Skorupski, D. H. Lenz, R. K. Taylor, and B. L. Bassler. 2002. Parallel quorum sensing systems converge to regulate virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Cell 110:303-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moorthy, S., and P. I. Watnick. 2004. Genetic evidence that the Vibrio cholerae monolayer is a distinct stage in biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 52:573-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schembri, M. A., K. Kjaergaard, and P. Klemm. 2003. Global gene expression in Escherichia coli biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 48:253-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vance, R. E., J. Zhu, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2003. A constitutively active variant of the quorum-sensing regulator LuxO affects protease production and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 71:2571-2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watnick, P., and R. Kolter. 2000. Biofilm, city of microbes. J. Bacteriol. 182:2675-2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watnick, P. I., and R. Kolter. 1999. Steps in the development of a Vibrio cholerae El Tor biofilm. Mol. Microbiol. 34:586-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watnick, P. I., C. M. Lauriano, K. E. Klose, L. Croal, and R. Kolter. 2001. The absence of a flagellum leads to altered colony morphology, biofilm development and virulence in Vibrio cholerae O139. Mol. Microbiol. 39:223-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiteley, M., M. G. Bangera, R. E. Bumgarner, M. R. Parsek, G. M. Teitzel, S. Lory, and E. P. Greenberg. 2001. Gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature 413:860-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yildiz, F. H., N. A. Dolganov, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2001. VpsR, a member of the response regulators of the two-component regulatory systems, is required for expression of vps biosynthesis genes and EPS(ETr)-associated phenotypes in Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. J. Bacteriol. 183:1716-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yildiz, F. H., and G. K. Schoolnik. 1999. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:4028-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu, J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 2003. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev. Cell 5:647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu, J., M. B. Miller, R. E. Vance, M. Dziejman, B. L. Bassler, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2002. Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3129-3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]