Abstract

The endophytic diazotroph Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus secretes a constitutively expressed levansucrase (LsdA, EC 2.4.1.10) to utilize plant sucrose. LsdA, unlike other extracellular levansucrases from gram-negative bacteria, is transported to the periplasm by a signal-peptide-dependent pathway. We identified an unusually organized gene cluster encoding at least the components LsdG, -O, -E, -F, -H, -I, -J, -L, -M, -N, and -D of a type II secretory system required for LsdA translocation across the outer membrane. Another open reading frame, designated lsdX, is located between the operon promoter and lsdG, but it was not identified in BLASTX searches of the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases. The lsdX, -G, and -O genes were isolated from a cosmid library of strain SRT4 by complementation of an ethyl methanesulfonate mutant unable to transport LsdA across the outer membrane. The downstream genes lsdE, -F, -H, -I, -J, -L, -M, -N, and -D were isolated through chromosomal walking. The high G+C content (64 to 74%) and the codon usage of the genes identified are consistent with the G+C content and codon usage of the standard G. diazotrophicus structural gene. Sequence analysis of the gene cluster indicated that a polycistronic transcript is synthesized. Targeted disruption of lsdG, lsdO, or lsdF blocked LsdA secretion, and the bacterium failed to grow on sucrose. Replacement of Cys162 by Gly at the C terminus of the pseudopilin LsdG abolished the protein functionality, suggesting that there is a relationship with type IV pilins. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis revealed conservation of the type II secretion operon downstream of the levansucrase-levanase (lsdA-lsdB) locus in 14 G. diazotrophicus strains representing 11 genotypes recovered from four different host plants in diverse geographical regions. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a type II pathway for protein secretion in the Acetobacteraceae.

Gluconacetobacter (formerly Acetobacter) diazotrophicus is a nonpathogenic, nitrogen-fixing endophyte of sugarcane and other predominantly sucrose-rich crops (11, 20, 47). This gram-negative bacterium lacks a sucrose transport system (3) and depends on the secretion of a constitutively expressed levansucrase (LsdA, EC 2.4.1.10) to utilize plant sucrose (16, 17). The levansucrase gene (lsdA) and an exolevanase gene (lsdB) downstream form a chromosomal operon with a high level of conservation among G. diazotrophicus isolates (17, 26).

All known levansucrases are extracellular proteins, although they follow different secretion routes. Levansucrase secretion in gram-positive bacteria involves cleavage of signal-peptide-containing precursors in Bacillus subtilis (43), Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (46), Geobacillus stearothermophilus (24), Paenibacillus polymyxa (7), Streptococcus salivarius (34), Actinomyces naeslundii (6), Arthrobacter nicotinovorans (36), and Lactobacillus reuteri (49). However, with the exception of LsdA, the other gram-negative levansucrases characterized so far are secreted by a signal-peptide-independent pathway; this occurs in Zymomonas mobilis (41), Erwinia amylovora (14), Rahnella aquatilis (42), Pseudomonas syringae (18, 23), and Gluconacetobacter xylinus (45). LsdA is synthesized as a precursor with a 30-residue N-terminal signal peptide, which is cleaved off during transport to the periplasm, where the enzyme adopts its final conformation. Then, in a rate-limiting step, the mature LsdA is transferred across the outer membrane and released into the extracellular medium without further proteolytic cleavage (15).

A wide spectrum of gram-negative bacteria, mainly plant- and animal-interacting species, utilize the type II secretion pathway for extracellular release of particular proteins, such as hydrolytic enzymes and toxins. Following translocation to the periplasm by the signal-peptide-dependent Sec or TAT system (32, 52), the folded substrate protein is transported across the outer membrane by the type II secretion apparatus, consisting of a multiprotein complex of at least 12 components (reviewed in reference 38).

Here we report that the endophytic bacterium G. diazotrophicus possesses a type II secretion operon required for LsdA transport across the outer membrane. The locus was identified downstream of the levansucrase-levanase (lsdA-lsdB) operon on the chromosome of the 14 strains tested, recovered from different host plants in diverse geographical regions. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a type II secretion pathway in the Acetobacteraceae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and plasmids.

Escherichia coli strains DH5α [φ80dlacZΔM15 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169] and S17-1 {thi pro hsdR recA [RP4-2(Tc::Mu) (Km::Tn7)]} (40) were used as a cloning host and a conjugative donor host, respectively. Both strains were grown at 37°C in Luria broth. The G. diazotrophicus strains listed in Table 1 were grown at 28°C in LGIE medium containing 5% (wt/vol) sucrose and 1% (vol/vol) glycerol (4). Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1; tetracycline, 20 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 30 μg ml−1; and kanamycin, 30 μg ml−1 for E. coli and 120 μg ml−1 for G. diazotrophicus. Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

G. diazotrophicus strains used in this study

| Strain | Description and/or sourcea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SRT4 | ET 1, stem tissue of sugarcane, Havana, Cuba | 17 |

| UAP 5560 | ET 1, stem tissue of sugarcane, Morelos, Mexico | 10 |

| CFNE 550 | ET 2, sugarcane mealybug, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 9 |

| PAI 5T | ET 3, root tissue of sugarcane, Alagoas, Brazil | 10 |

| PSP 22 | ET 4, leaf tissue of sugarcane, Sao Paulo, Brazil | 9 |

| PAI 3 | ET 5, root tissue of sugarcane, Alagoas, Brazil | 9 |

| I772 | ET 6, sugarcane mealybug, Ayr, Australia | 9 |

| PRC 1 | ET 7, stem tissue of Cameroon grass, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 9 |

| CFN-Cf52 | ET 9, root tissue of coffee plant, Guerrero, Mexico | 20 |

| CFN-Cf50 | ET 11, root tissue of coffee plant, Guerrero, Mexico | 20 |

| UAP-Cf51 | ET 12, rhizosphere of coffee plant, Chiapas, Mexico | 20 |

| UAP-Cf53 | ET 14, rhizosphere of coffee plant, Chiapas, Mexico | 20 |

| UAP-Ac10 | ET 1, rhizosphere of pineapple plant, Veracruz, Mexico | 47 |

| UAP-Ac7 | ET 1, leaf tissue of pineapple plant, Veracruz, Mexico | 47 |

| M31 | EMS-treated SRT4 mutated at lsdG unable to secret LsdA | 4, 15 |

| AD5 | SRT4 lsdA::nptII-ble unable to produce LsdA | 15 |

| AD6 | SRT4 lsdG::nptII-ble unable to secret LsdA | This study |

| AD8 | SRT4 lsdO::nptII-ble unable to secret LsdA | This study |

| AD9 | SRT4 lsdF::nptII unable to secret LsdA | This study |

ET, electrophoretic type. Different ETs correspond to different genotypes.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pPW12 | IncP mobilizable cosmid pLAFRI with EcoRI-BamHI-EcoRI linker, Tcr, 21.6 kbp | 13 |

| pRK293 | IncP mobilizable cloning vector, Tcr Kmr, 21.3 kbp | 12 |

| pUC8 | ColE1 cloning vector, Apr, 2.7 kbp | 50 |

| pUC19 | ColE1 cloning vector, Apr, 2.7 kbp | 54 |

| pBluescript SK(+) | ColE1 cloning vector, Apr, 3.0 kbp | 1 |

| pUC4KIXX | pUC4K-based plasmid carrying the Tn5 Kmr and Blr resistance genes, Apr Kmr Blr, 4.0 kbp | 5 |

| pUCNCO | ColE1 cloning vector, pUC8 with ACCATGG sequence inserted between BamHI and HincII sites, Apr, 2.7 kbp | This study |

| p21R1 | pPW12 with a 20-kbp insert of G. diazotrophicus SRT4 containing the lsdAB locus and partial type II secretion locus, Tcr, 42 kbp | 4 |

| pALS5 | 5,181-bp SalI-EcoRI fragment from p21R1 inserted into pUC19: carries lsdABX, Apr, 7.9 kbp | 4 |

| pALS15 | pRK293 with HindIII-linearized pALS10 carrying the SRT4 lsdA gene in a 2,339-bp BglII fragment, Apr Tcr 27.2 kbp | 4 |

| pALS30 | 7.7-kbp BamHI-partial EcoRI fragment from p21R1 inserted into pUC8, carries region upstream of lsdA, Apr, 10.4 kbp | This study |

| pALS31 | 8.7-kbp BamHI-partial EcoRI fragment from p21R1 inserted into pUC8, carries region upstream of lsdA, Apr, 11.4 kbp | This study |

| pALS32 | 4,614-bp BamHI-partial EcoRI fragment from p21R1 inserted into pUC8, carries lsdBXGO, Apr, 7.3 kbp | This study |

| pALS33 | HindIII-linearized pALS30 inserted at the HindIII site of pRK293, Apr Tcr, 31.7 kbp | This study |

| pALS34 | HindIII-linearized pALS31 inserted at the HindIII site of pRK293, Apr Tcr, 32.7 kbp | This study |

| pALS35 | BamHI-linearized pALS32 inserted at the BamHI site of pPW12, Apr Tcr, 28.9 kbp | This study |

| pALS60 | 198-bp PCR band amplified from pALS5 inserted at the SmaI site of pUC19, carries N-terminal region of lsdA, Apr, 2.9 kb | This study |

| pALS89 | pUCNCO containing a 1,491-bp NcoI-HincII fragment with the nptII-ble cassette from pUC4KIXX inserted at the EcoRI site of lsdG, Apr Kmr Blr, 5.8 kbpa | This study |

| pALS113 | 1,050-bp PCR band amplified from pALS32 inserted at the SalI-BamHI sites of pUC19, carries wild-type lsdG, Apr, 3.7 kbpa | This study |

| pALS114 | 1,050-bp PCR band amplified from pALS32 inserted at the SalI-BamHI sites of pUC19, carries mutated lsdG (C162G) Apr, 3.7 kbpa | This study |

| pALS117 | HindIII-linearized pALS113 inserted at the HindIII site of pRK293, Apr Tcr, 24.8 kbp | This study |

| pALS118 | HindIII-linearized pALS114 inserted at the HindIII site of pRK293, Apr Tcr, 24.8 kbp | This study |

| pALS119 | 3,527-bp HindIII-SphI fragment of G. diazotrophicus SRT4 genome inserted into pUC19, carries lsdEF, Apr, 6.2 kbp | This study |

| pALS127 | pALS119 with the 1.2-kbp SmaI nptII cassette from pUC4KIXX inserted at the EcoRV site of lsdF, Apr Kmr, 7.4 kbp | This study |

| pALS130 | pBluescript SK (+) containing a 7,551-bp BamHI-KpnI fragment with the nptII-ble cassette from pUC4KIXX inserted at the HindIII site of lsdO, Apr Kmr Blr, 12.1 kbpa | This study |

| pALS141 | 1,967-bp SmaI-BglII fragment from pALS5 inserted at SmaI-BamHI sites in pALS60 carries lsdA, Apr 4.8 kb | This study |

| pALS143 | 1,432-bp SacII-KpnI fragment of G. diazotrophicus SRT4 genome inserted into pBluescript SK (+), carries lsdHIJ, Apr, 4.3 kbp | This study |

| pALS152 | 3,679-bp SalI-EcoRI fragment of G. diazotrophicus SRT4 genome inserted into pBluescript SK(+), carries lsdJLMN and partial lsdD, Apr, 6.4 kbp | This study |

| pALS182 | 584-bp PCR band amplified from pALS5 digested with HindIII-NcoI plus 2,114-bp NcoI-NruI fragment from pALS141 inserted at HindIII-SmaI sites in pUCNCO, carries lsdA under control of 552-bp region upstream of lsdX, Apr, 4.8 kb | This study |

| pALS184 | HindIII-linearized pALS182 inserted at the HindIII site of pRK293, Apr Tcr, 26.6 kbp | This study |

See text.

DNA manipulation and analysis.

Standard methods were used for recombinant DNA procedures (37). High-specific-activity DNA probes were generated by using a Prime-a-Gene labeling kit (Promega) with [α-32P]dATP (>3,000 Ci mmol−1; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Automatic chain termination DNA sequencing was performed on both strands with an ALFexpressII DNA sequencer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The nucleotide sequences were compiled and analyzed by using the BioSOS program package (8). The BLAST program (2) was used for similarity searches in protein databases, and the CLUSTAL W program (48) was used to obtain multiple-sequence alignments. Promoter prediction was performed by the NNPP method (35) (software is available at the website http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html).

Complementation experiments.

Broad-host-range plasmids were used to transform E. coli strain S17.1 and were mobilized to G. diazotrophicus by conjugative mating as previously described (4). The transconjugants were selected on LGIE agar medium supplemented with tetracycline and chloramphenicol; the latter antibiotic was used to counterselect E. coli donors. Intracellular and extracellular LsdA activities of mucous and nonmucous colonies were examined as described previously (15).

Cloning of type II secretion system genes from G. diazotrophicus strain SRT4.

Cosmid p21R1 was digested with BamHI totally and EcoRI partially and was electrophoresed in an LMP agarose gel (Gibco-BRL). An agarose slice containing fragments ranging from 3.5 to 20 kbp long was melted and mixed in a ligation reaction with BamHI-EcoRI-digested pUC8 vector. The ligation products were used to transform E. coli DH5α. Three resultant plasmids with different restriction patterns, designated pALS30, pALS31, and pALS32, were inserted into a broad-host-range vector to obtain the mobilizable plasmids pALS33, pALS34, and pALS35, respectively (Fig. 1), which were tested for complementation of LsdA secretion in the G. diazotrophicus mutant M31. Cloning of a 7.4-kbp fragment downstream of the complementing region of pALS35 was achieved by three successive chromosomal walking steps. Three partial SRT4 DNA libraries containing 3- to 4-kbp HindIII-SphI fragments, 1- to 2-kbp SacII-KpnI fragments, and 4- to 6-kbp SalI-EcoRI fragments were constructed in pUC19 or pBluescript SK(+). Hybridizations performed with around 1,000 colonies from each library yielded three positive overlapping clones, pALS119, pALS143, and pALS152 (Fig. 2). The inserts of pALS32, pALS119, pALS143, and pALS152 were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes for subcloning and sequencing.

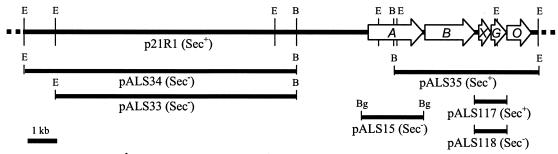

FIG. 1.

Localization of the region of the library cosmid p21R1 complementing LsdA secretion in mutant M31. lsd genes are represented by arrows. lsdA and lsdB encode levansucrase and levanase, respectively. lsdX, -G, and -O are the first genes of the type II secretion operon. The ability of each plasmid to restore LsdA secretion is indicated in parentheses. Plasmid pALS118 encodes a mutated LsdG (C126G). Restriction sites: E, EcoRI; B, BamHI; Bg, BglII.

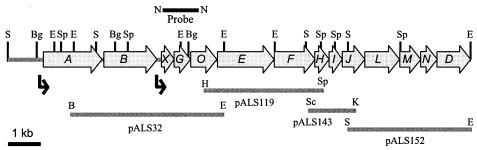

FIG. 2.

Physical and genetic map of the G. diazotrophicus levansucrase-levanase and type II secretion operons. Genes are represented by arrows and are identified by italic letters. The lsdD gene is incomplete. The bent arrows indicate promoter positions. Inserts of the recombinant plasmids pALS32, pALS119, pALS143, and pALS152 are indicated. Restriction sites: B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; S, SalI; N, NcoI; Sc, SacII; Sp, SphI. The 1.1-kbp NcoI band of pALS32 was used as a hybridization probe for RFLP analysis.

Expression of the lsdA gene from the promoter region upstream of lsdX.

The region encoding the amino terminus of lsdA was amplified from pALS5 by using primers 5′-CTTCAGGAGGATGCCATGGCGCATGTACGCC-3′ and 5′-CAGCGACCGCCCGGGGAAGAGCGGGCCGCC-3′ in a 198-bp PCR band and was inserted at the SmaI site of pUC19 in the direction opposite that of the lac promoter. The resulting plasmid, designated pALS60, was digested with SmaI-BamHI and ligated to the 1,967-bp SmaI-BglII fragment from pALS5, and the construct was designated pALS141. A band containing the 552-bp region upstream from lsdX was amplified by PCR from plasmid pALS5 with primers 5′-CTACGGGGACCGGAAGCTTCCGCAGG-3′ and 5′-CGATCGGCAATTACCATGGCCACACC-3′. This band was digested at the HindIII and NcoI sites introduced by the PCR and ligated in a triple-ligation procedure to HindIII-SmaI-digested pUCNCO and the 2,114-bp NcoI-NruI fragment from pALS141 to obtain pALS182. Plasmid pALS184 resulted from insertion of HindIII-linearized pALS182 into the HindIII site of pRK293 (Table 2). LsdA activity was assayed in cell extracts of E. coli DH5α carrying pALS182 and in culture supernatants of the G. diazotrophicus mutant AD5 carrying pALS184.

Cloning of lsdX and lsdG genes from nonsecreting mutant M31.

The insert of the complementing plasmid pALS35 included a 1.1-kbp NcoI fragment containing the type II secretion genes lsdX and lsdG of strain SRT4. Since this fragment had an internal PstI site, total DNA from mutant M31 was digested with NcoI and PstI and electrophoresed in an LMP agarose gel. DNA bands ranging from 400 to 700 bp long were isolated from the gel and ligated to the NcoI-PstI-digested pUCNCO vector. The E. coli transformants were screened by hybridization to the 1.1-kbp NcoI band from pALS32 (Fig. 2). Positive plasmids with the 640- and 440-bp NcoI-PstI inserts were purified and sequenced.

Gene disruption by marker exchange.

The suicide plasmids pALS89, pALS127, and pALS130 were used to create disruptions in the genes lsdG, lsdF, and lsdO, respectively, on the chromosome of G. diazotrophicus SRT4 by marker exchange. Plasmid pALS89 was constructed by inserting in a quadruple-ligation procedure the 546-bp NcoI-EcoRI band from pALS5, the 1.6-kbp EcoRI fragment from pUC4KIXX containing the kanamycin-bleomycin resistance (nptII-ble) cassette, and the 945-bp EcoRI-HincII fragment from pALS32 into NcoI-HincII-digested pUCNCO. Plasmid pALS130 was constructed by joining in a quadruple-ligation reaction the 3,991-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment from pALS32, the 1.6-kbp HindIII nptII-ble cassette from pUC4KIXX, and the 3,560-bp HindIII-KpnI fragment from pALS119 in BamHI-KpnI-digested pBluescript SK(+). The three plasmids were separately introduced into G. diazotrophicus SRT4 by electroporation, and the recombinant colonies were selected on kanamycin-containing LGIE medium plates as described previously (4). Insertion of the nptII marker into the lsd type II secretion genes in the chromosomes of nonmucous colonies was confirmed by Southern hybridization. Intracellular and extracellular LsdA activities in the mutants were examined as described previously (15).

Site-directed mutagenesis of Cys162 in the lsdG gene of G. diazotrophicus SRT4.

A 1,050-bp DNA fragment comprising the promoter and the first two genes (lsdX and lsdG) of the SRT4 type II secretion operon was amplified by PCR by using plasmid pALS32 as the template and primers 5′-TGCCGAAGGGGTCGACGCCACCATTCACG and 5′-CATGGATCCCACGATCAGGGATTGCAGATC with base substitutions (boldface type) to create SalI and BamHI restriction sites (underlined). The PCR product was digested with SalI-BamHI and inserted into the corresponding sites of pUC19 to obtain plasmid pALS113. In another PCR the TGC codon (Cys162) of the SRT4 lsdG gene was replaced with GGC (Gly) by using the same template and upstream primer along with downstream primer 5′-CATGGATCCCACGATCAGGGATTGCCGATC. The A-to-C substitution (boldface type) in the latter primer replaces the TGC codon with GGC and abolishes the BglII site at the end of lsdG. The amplified 1,050-bp fragment was digested with SalI-BamHI and inserted into pUC19 to obtain plasmid pALS114. Plasmids pALS113 and pALS114 were linearized with HindIII and inserted into the broad-host-range vector pRK293 to obtain the mobilizable plasmids pALS117 and pALS118, respectively (Fig. 1), which were tested for complementation of LsdA secretion in ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS)-treated mutant M31.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the identified type II lsd genes is available in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession number L41732.

RESULTS

Identification of a gene cluster encoding a type II protein secretory pathway in G. diazotrophicus SRT4.

Seven G. diazotrophicus mutants that had active LsdA in the periplasm but were unable to transfer the enzyme across the outer membrane were previously isolated by EMS treatment of strain SRT4 (4). Introduction of the library cosmid clone p21R1 restored the Sec+, levan-forming (mucous colony) phenotype in one of the seven mutants (Fig. 1). This mutant, designated M31, was fully complemented by the derivative plasmid pALS35 containing a region downstream of the structural levansucrase gene (lsdA) and the levanase-encoding gene (lsdB). Introduction of plasmid pALS15 carrying only the lsdA gene increased the amount of LsdA in the periplasm (data not shown) but did not restore protein secretion (Fig. 1).

Sequencing of the 4,614-bp DNA insert of pALS35 revealed the presence of three consecutive open reading frames (ORFs) in the same orientation as the lsdA-lsdB operon (Fig. 1). The first ORF, designated lsdX, encodes a polypeptide with no detected similarities in databases. The second ORF encodes a polypeptide with the highest identity scores for the type II secretion component GspG (Table 3), and therefore it was designated lsdG. The N-terminal part of the deduced LsdG also showed a high degree of similarity with type IV pilins. The translation initiation codon of lsdG is an ATG, which is not preceded by a Shine-Dalgarno sequence but overlaps by one base lsdX, suggesting that the two genes are translated consecutively without ribosome dissociation. The third ORF, designated lsdO, starts with an ATG codon located 12 bp downstream of the lsdG stop codon and encodes a polypeptide with the essential characteristics of the type IV prepilin peptidase family members. The gene product is highly similar to the GspO component of several type II secretory pathways (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Similarity between type II secretion components of G. diazotrophicus SRT4 and their homologues in other bacteriaa

| Species | % Similarity

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LsdG (164, −1)b | LsdO (261, 15) | LsdE (566, 23) | LsdF (409, 7) | LsdH (140, −8) | LsdI (134, −1) | LsdJ (228, −1) | LsdL (348, −1) | LsdM (210, 6) | LsdN (164, −1) | LsdD (ND, −1) | |

| X. campestris | 45 | 42 | 61 | 51 | 35 | 37 | 32 | 35 | 33 | 25 | 38 |

| V. cholerae | 41 | 43 | 52 | 50 | 22 | 28 | 30 | 25 | 28 | 18 | 28 |

| P. aeruginosa | 41 | 43 | 50 | 51 | 30 | 29 | 28 | 26 | 29 | 22 | 25 |

| A. hydrophila | 40 | 45 | 51 | 47 | 23 | 27 | 33 | 23 | 26 | 16 | 30 |

| E. carotovora | 39 | 42 | 51 | 51 | 23 | 32 | 27 | 26 | 28 | 18 | 22 |

| E. coli | 39 | 38 | 48 | 46 | 25 | 27 | 27 | 21 | 26 | 17 | 28 |

| K. pneumoniae | 38 | 40 | 50 | 50 | 28 | 30 | 32 | 23 | 22 | 19 | 29 |

| E. chrysanthemi | 34 | 43 | 51 | 49 | 24 | 32 | 30 | 21 | 29 | 25 | |

Two residues were considered similar if they belong to one of the following groups: AGS, DE, FWYH, ILMV, QN, RK, and SAT. The highest similarity scores are indicated by boldface type. The LsdD similarity values correspond to alignments of the translated incomplete gene. Comparisons were performed with protein sequences reported in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ nucleotide sequence records with the following accession numbers: X. campestris, X59079, L02630, AE012165, and U12432; V. cholerae, L33796; P. aeruginosa, X62666, AE004734, and M61096; A. hydrophila, X66504; E. carotovora, X70049; E. coli, AE000409; K. pneumoniae, M32613; and E. chrysanthemi, L02214.

The numbers in parentheses are the number of amino acids in the precursor protein, followed by the distance between an ORF and its predecessor in the operon. ND, not determined.

Through chromosomal walking, three contiguous fragments downstream of lsdO were cloned in plasmids pALS119, pALS143, and pALS152 (Fig. 2). The assembled nucleotide sequence contained eight full ORFs and one partial ORF, which were designated lsdE, -F, -H, -I, -J, -L, -M, -N, and -D based on their similarities to components of type II secretory systems (Table 3). Most of the genes have ATG translation initiation codons; the only exception is lsdH, which begins with TTG. The initiation and stop codons of the lsdF, -H, -I, -J, -L, -M, -N, and -D genes overlap or are separated by seven or fewer bases. The lsdE start codon is located 23 bp downstream of the lsdO stop codon, and it is preceded by the putative ribosome-binding sequence AGGAA at position −13, suggesting that lsdE is translated independent of lsdO. However, the presence of a small ORF comprising the 22-bp intergenic region and overlapping lsdO and lsdE by one base also makes coupled translation of these genes possible.

The consecutive arrangement of the 12 genes suggests the existence of an operon. A 50-bp sequence starting 104 bp upstream of lsdX was predicted to be a transcriptional promoter with a probability of 99%. The putative transcription start is flanked by TTGAAATCCC direct repeats. The first ATG of lsdX is preceded by the potential ribosome-binding sequence AGAAGGAG at position −10 and should initiate translation of the polycistronic mRNA. Fusion of the 548-bp region upstream from lsdX, containing the putative promoter, with the lsdA gene in pALS182 and pALS184 led to constitutive LsdA expression in the recombinant hosts E. coli and G. diazotrophicus, respectively.

The G+C contents of the type II secretion genes from strain SRT4 ranged from 64 to 74%, which is consistent with the high G+C content of the G. diazotrophicus genome. The codon usage of the 12 genes shows a strong preference for C and G (78 to 91%) in the third position of the triplets, except for the amino acids Glu, His, Asn, and Tyr. This codon usage is basically shared by other G. diazotrophicus structural genes, including lsdA (4) and lsdB (26).

Genetic features of the G. diazotrophicus type II secretion system.

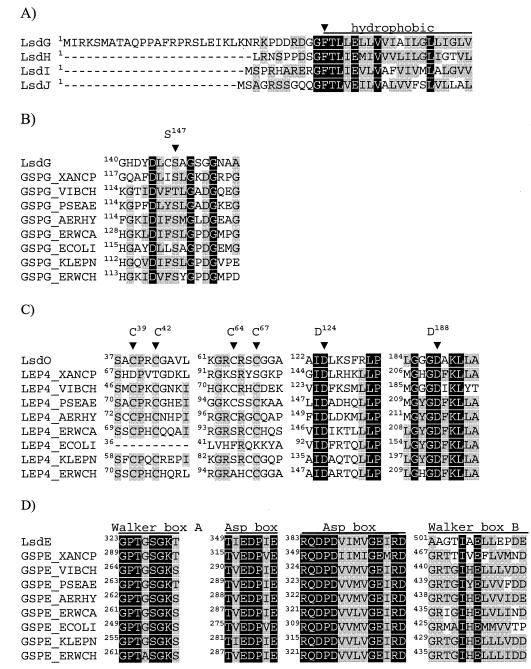

The deduced sequences of the G. diazotrophicus type II components LsdG, -H, -I, and -J have the main characteristics of type IV pilins and pseudopilins. Their N-terminal regions have the consensus pattern G-F-T-L-(LIV)-E, with the putative peptidase cleavage site between Gly and Phe, followed by a stretch of about 20 highly hydrophobic residues. Most of the signal peptides are hydrophobic and short (9 to 11 residues); the only exception is the signal peptide for LsdG, which has 34 residues and is among the longest signals in the family (Fig. 3A). At position 147 the precursor LsdG contains a conserved Ser residue that aligns with Ser121 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa XcpT (GspG) involved in the protein interaction with the component XcpR (GspE) (21) (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Partial protein sequence alignments. (A) Alignment of G. diazotrophicus pseudopilin N terminus. The arrowhead indicates the putative beginning of mature pilins. (B, C, and D) Alignment of LsdG, LsdO, and LsdE with their homologues in other type II secretion systems. S147 in LsdG, C39, C42,C 64, C67, D124, and D188 in LsdO, and Walker A, Walker B, and aspartic acid boxes in LsdE are indicated above the alignments. The sequences, identified by their SwissProt entry names, correspond to the following species: Xanthomonas campestris, Vibrio cholerae, P. aeruginosa, Aeromonas hydrophila, Erwinia carotovora, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Erwinia chrysanthemi. Identical and similar residues are indicated by white letters on a black background and by black letters on a gray background, respectively. Groups of residues considered similar in the alignment are described in Table 3, footnote a. The numbers in the alignment indicate the positions of the residues in the precursor proteins.

Multiple-sequence alignments of other G. diazotrophicus type II components with their counterparts from diverse gram-negative bacteria revealed conservation of several remarkable residues. The putative prepilin peptidase and methylase LsdO contains the residues Asp124 and Asp188 that must be located at the enzyme active site (22), the residue Gly62 probably involved in the methyltransferase activity (29), and the residues Cys39, Cys42, Cys64, and Cys67, whose analogues in P. aeruginosa PilD are required for efficient activity (44) (Fig. 3C). However, not all members of the PilD family contain the four Cys residues, suggesting that they are not cysteine proteases but are aspartic proteases (22). The putative nucleotide-binding protein LsdE contains a domain rich in glycine and lysine (GPTGSGKT) that extends from residue 323 to residue 330 and resembles the functional Walker box A (31, 53). A less-conserved Walker box B is also present in LsdE (501AAGTIAELLEPDE512) but includes only one Gly instead of two Gly residues, which is the form that occurs in most of the family members. LsdE possesses two aspartic acid boxes (residues 349 to 355 and 383 to 396), which are highly conserved in the GspE family (Fig. 3D).

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the type II secretion locus in 14 representative G. diazotrophicus strains.

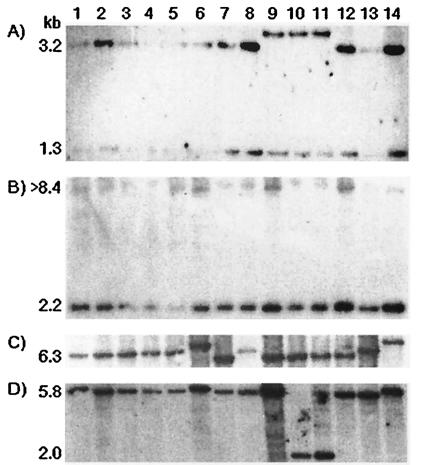

Total DNA from 14 G. diazotrophicus strains representing 11 different genotypes (electrophoretic types) (Table 1) was digested with EcoRI, BglII, SphI, or SalI, and probed with a 1.1-kbp NcoI fragment containing the lsdX and lsdG genes and part of the lsdO gene from strain SRT4 (Fig. 2). Two hybridizing EcoRI fragments (1.3 and 3.2 kbp) were detected in 11 of the 14 isolates, including the plasmidless strain PAL 5T (Fig. 4A). Replacement of the largest band by a new 3.8-kbp fragment in the coffee plant-associated strains CFN-Cf52, CFN-Cf50, and UAP-Cf51 corresponded to the absence of the second EcoRI site in the lsdA gene, as determined previously (17). The 14 strains had the expected 2.2-kbp BglII fragment extending from lsdB to the end of lsdG and an additional band that must extend beyond the lsdD gene (Fig. 4B). DNA digestion with SalI or SphI revealed in each case a single hybridizing band that was three different sizes in the strains (Fig. 4C and D). The polymorphisms are located in the type II secretion operon considering that all the isolates contain the SalI and SphI sites of the upstream lsdA gene (17). The 6.3-kbp SalI band of strain SRT4 is conserved in five of the seven sugarcane isolates, as well as in strains PRC 1 and UAP-Ac7 recovered from Cameron grass and a pineapple plant, respectively. Two strains from different hosts produced a band at approximately 7.6 kbp because of the loss of the SalI site in the lsdF gene. A shorter band (∼5.5 kbp) appeared in the four coffee plant isolates and the sugarcane endophyte PAl 3 due to the presence of a new SalI site, probably at the beginning of the lsdF gene. The majority of the strains shared the 5.8-kbp SphI fragment of SRT4. Strains PAl 3 and UAP-Ac7 showed a hybridizing band at approximately 6.2 kbp, revealing the loss of the SphI site in the lsdH gene, whereas hybridization in strains CFN-Cf50 and UAP-Cf51 corresponded to a band at about 2 kbp, indicative of the occurrence of an SphI site in lsdO.

FIG. 4.

RFLP analysis of the type II secretion locus in 14 G. diazotrophicus strains. Total DNA was digested with EcoRI (A), BglII (B), SalI (C), and SphI (D) and probed with a 32P-labeled 1.1-kbp NcoI fragment carrying the lsdX and lsdG genes and partial lsdO gene from strain SRT4 (Fig. 2). The sizes of SRT4 hybridizing bands are indicated. Lane 1, strain SRT4; lane 2, strain UAP 5560; lane 3, strain CFNE 550; lane 4, strain PAl 5T; lane 5, strain PSP 22; lane 6, strain PAl 3; lane 7, strain 1772; lane 8, strain PRC 1; lane 9, strain CFN-Cf52; lane 10, strain CFN-Cf50; lane 11, strain UAP-Cf51; lane 12, strain UAP-Cf53; lane 13, strain UAP-Ac10; lane 14, strain UAP-Ac7.

In summary, 11 polymorphisms were detected for the 70 restriction sites examined in type II secretion genes of the 14 strains. Six of these polymorphisms occurred in the four strains recovered from coffee plants.

Functional analysis of the type II secretion genes in strain SRT4.

To assess the implications of the type II secretion operon in LsdA secretion, the lsdG, lsdO, and lsdF genes were independently disrupted in the chromosome of wild-type strain SRT4. The ColE1 derivative plasmids pALS88, pALS130, and pALS127 carrying the nptII cassette inserted at the EcoRI site of lsdG, the HindIII site of lsdO, and the EcoRV site of lsdF, respectively, were introduced by electroporation into strain SRT4. Kanamycin-resistant, nonmucous colonies occurred in all three cases as a consequence of double-recombination events, resulting in replacement of the chromosomal target genes by the disrupted cassettes of the plasmids, as confirmed by Southern hybridization (data not shown). The lsdG::nptII, lsdO::nptII, and lsdF::nptII mutants, designated AD6, AD8, and AD9, respectively, did not show extracellular levansucrase activity, but the intracellular activity increased about fourfold due to accumulation of LsdA in the cell periplasm (Table 4). This finding indicates that the type II secretion operon is responsible for LsdA transfer across the outer membrane. The mutants failed to grow in liquid LGIE medium containing sucrose as the sole carbon source, corroborating the hypothesis that LsdA secretion is required for sucrose utilization by G. diazotrophicus.

TABLE 4.

LsdA secretion in G. diazotrophicus strainsa

| Strain | Intracellular LsdA activity (U mg−1) | Extracellular LsdA activity (U ml−1) |

|---|---|---|

| SRT4 | 20 ± 4 | 32 ± 4 |

| M31 | 75 ± 6 | 5 ± 2 |

| AD6 | 72 ± 5 | 4 ± 2 |

| AD8 | 69 ± 5 | 5 ± 2 |

| AD9 | 77 ± 6 | 5 ± 2 |

| M31(pALS117) | 19 ± 3 | 28 ± 4 |

| M31(pALS118) | 73 ± 5 | 5 ± 2 |

Bacteria from a 1-ml culture, (optical density at 620 nm, 8 ± 0.2) were spun down at 6,500 × g for 15 min. Supernatants were assayed for extracellular LsdA activity. Cells were washed in Tris-EDTA buffer; resuspended in 0.5 ml of distilled water, and disrupted in the presence of 0.2% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate and 4% (vol/vol) chloroform with incubation for 15 min at room temperature. Chloroform and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 6,500 × g for 5 min, and cell extracts were assayed for intracellular LsdA activity. The values are means ± standard deviations (n = 6).

Cloning and sequencing of a 1.1-kbp NcoI fragment isolated from the EMS-treated, nonsecreting mutant M31 revealed the occurrence of a single mutation consisting of a G-to-A transition in the lsdG gene. This mutation transformed a TGG codon (Trp111) into a TGA (stop) codon, eliminating the last 54 residues of the original polypeptide. Complementation experiments with plasmid pALS117 carrying only the lsdX and lsdG genes (Fig. 1 and Table 4) confirmed that the G-to-A substitution mutation in M31 had no polar effect on expression of the type II genes downstream of lsdG.

The pseudopilin LsdG has two C-terminal Cys residues at positions 146 and 162, which may form a disulfide bond in the nonreducing environment of the periplasm. By PCR-mediated mutation the TGC codon (Cys162) was replaced by GGC (Gly) in plasmid pALS118. This plasmid failed to restore LsdA secretion in the M31 mutant (Fig. 1 and Table 4), indicating that Cys162 has a key role in LsdG functionality.

DISCUSSION

G. diazotrophicus secretes levansucrase (LsdA) by a two-step mechanism involving the removal of a 30-residue N-terminal signal peptide during transport to the periplasm and transfer of the folded mature protein across the outer membrane via a type II secretion system. Proteins which are substrates of type II secretion systems have been found to use the Sec or TAT machinery for crossing the cytoplasmic membrane (38, 52). The LsdA signal peptide has the essential features of a Sec-dependent signal peptide. By contrast, other gram-negative bacteria, including the close relative Gluconacetobacter xylinus, secrete levansucrases by a signal-peptide-independent pathway (14, 18, 23, 41, 42, 45). Some of these enzymes have been localized and are fully active in the periplasm of the native host or a recombinant E. coli strain (14, 18, 19, 23), and the occurrence of a type II secretion pathway responsible for their transfer across the outer membrane cannot be ruled out.

The G. diazotrophicus type II secretion operon must be transcribed constitutively, considering that the substrate LsdA is a constitutive enzyme (16, 17). The occurrence of overlaps or short distances between different type II lsd genes indicates that there is translational coupling, as occurs in the homologues in other bacteria. The G. diazotrophicus type II secretion locus has the unusual order lsdXGOEFHIJLMND, suggesting that there is favored translation of the unidentified protein LsdX and the putative major pseudopilin LsdG. Most of the genes initiate at ATG; the only exception is the minor pseudopilin gene lsdH, whose starting TTG codon may lower the translation rate. Other bacteria also have minor pseudopilin genes starting at GTG or TTG. The presence of a ribosome-binding site between the components lsdO and lsdE also reflects fine-tuning of translation of the system components.

The G. diazotrophicus pseudopilin LsdG differs from its counterparts in other type II systems in two main aspects. The LsdG signal peptide is the longest signal peptide among all of the GspG homologues and has similarities with the signal peptide of a hypothetical pilin-like protein from Synechocystis sp. (SPTREMBL, entry P73235). LsdG has two C-terminal Cys residues that likely form a disulfide bond in the nonreducing environment of the periplasm. An intramolecular disulfide bridge occurs in the C-terminal part of many type IV pilins and is essential for the correct alpha-beta roll fold and functionality of the fiber-forming pilin in Neisseria gonorrhoeae (28) and for functionality of the pseudopilin PulK in Klebsiella oxytoca (33). G. diazotrophicus failed to secrete LsdA after replacement of Cys162 by Gly in LsdG. This result suggests that LsdG shares structural and functional properties with type IV pilins and reinforces the idea that pseudopilins and type IV pilins function in similar ways. In this sense, two previous findings are relevant: PilA, the major IV pilin of P. aeruginosa, was shown to interact with pseudopilin XcpT (GspG) and is required for optimal function of the secreton (25); and the major pseudopilin GspG from different bacteria assembled into pili when it was overexpressed in E. coli (51).

The type II secretion locus was identified downstream of the levansucrase-levanase (lsdAB) locus on the chromosomes of all 14 tested G. diazotrophicus strains isolated from four different host plants in geographically distant regions. This finding suggests that the two loci were simultaneously inherited or acquired early in the process of speciation. In any case, the coding sequences have adjusted to the codon usage of the species. No polymorphisms and few polymorphisms were detected in the lsdAB (17) and type II secretion loci, respectively, of strains recovered from sugarcane, Cameroon grass, or pineapple plants. Both loci were much less conserved in the strains recovered from coffee plants. These findings support the hypothesis that there is limited genetic diversity among G. diazotrophicus populations that inhabit vegetatively propagated hosts (9, 10).

LsdA should have a fivefold β-propeller topology, like that recently determined for the B. subtilis levansucrase (27). Type II secreted proteins are rich in β-sheet content, and this structural feature may serve as a recognition signal for targeting of the periplasmic protein to the secretion apparatus (38). The N-terminal sequence of the G. diazotrophicus levanase (LsdB) has the essential characteristics of a Sec-dependent signal peptide (26). Similar to LsdA, LsdB was predicted to have a β-propeller fold (30) and might also be secreted via the type II secretory machinery. This issue could not be investigated since the particular conditions required for lsdB expression in G. diazotrophicus remain unknown.

Type II secretion systems have been identified mostly in relation to pathogenesis processes in plants and animals (39). By contrast, G. diazotrophicus is a nonpathogenic, nitrogen-fixing species. Considering that disruption of the type II secretion genes in strain SRT4 abolished sucrose utilization, we concluded that the LsdA-secreting system plays a key role in the beneficial interaction between G. diazotrophicus and sugarcane or other host plants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alting-Mees, M. A., and J. M. Short. 1989. pBluescript II: gene mapping vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:9494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez, B., and G. Martinez-Dretz. 1995. Metabolic characterization of Acetobacter diazotrophicus. Can. J. Microbiol. 41:918-924. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arrieta, J., L. Hernandez, A. Coego, V. Suarez, E. Balmori, C. Menendez, M. F. Petit-Glatron, R. Chambert, and G. Selman-Housein. 1996. Molecular characterization of the levansucrase gene from the endophytic sugarcane bacterium Acetobacter diazotrophicus SRT4. Microbiology 142:1077-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barany, F. 1985. Single-stranded hexameric linkers: a system for in-phase insertion mutagenesis and protein engineering. Gene 37:111-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergeron, L. J., E. Morou-Bermudez, and R. A. Burne. 2000. Characterization of the fructosyltransferase gene of Actinomyces naeslundii WVU45. J. Bacteriol. 182:3649-3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bezzate, S., S. Aymerich, R. Chambert, S. Czarnes, O. Berge, and T. Heulin. 2000. Disruption of the Paenibacillus polymyxa levansucrase gene impairs its ability to aggregate soil in the wheat rhizosphere. Environ. Microbiol. 2:333-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bringas, R., R. Ricardo, J. Fernández de Cossío, M. E. Ochagavía, A. Suárez, and R. Rodríguez. 1992. BioSOS: a program package for the analysis of biological sequences in the microcomputer. Biotecnol. Apl. 9:180-185. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caballero-Mellado, J., L. E. Fuentes-Ramirez, V. M. Reis, and E. Martinez-Romero. 1995. Genetic structure of Acetobacter diazotrophicus populations and identification of a new genetically distant group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3008-3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caballero-Mellado, J., and E. Martinez-Romero. 1994. Limited genetic diversity in the endophytic sugarcane bacterium Acetobacter diazotrophicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1532-1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavalcante, V. A., and J. Döbereiner. 1988. A new acid-tolerant nitrogen-fixation bacterium associated with sugarcane. Plant Soil 108:23-31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ditta, G., T. Schmidhauser, E. Yakobson, P. Lu, X. W. Liang, D. R. Finlay, D. Guiney, and D. R. Helinski. 1985. Plasmids related to the broad host range vector, pRK290, useful for gene cloning and for monitoring gene expression. Plasmid 13:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman, A. M., S. R. Long, S. E. Brown, W. J. Buikema, and F. M. Ausubel. 1982. Construction of a broad host range cosmid cloning vector and its use in the genetic analysis of Rhizobium mutants. Gene 18:289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geier, G., and K. Geider. 1993. Characterization and influence on virulence of the levansucrase gene from the fireblight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 42:387-404. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez, L., J. Arrieta, L. Betancourt, V. Falcon, J. Madrazo, A. Coego, and C. Menendez. 1999. Levansucrase from Acetobacter diazotrophicus SRT4 is secreted via periplasm by a signal-peptide-dependent pathway. Curr. Microbiol. 39:146-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez, L., J. Arrieta, C. Menendez, R. Vazquez, A. Coego, V. Suarez, G. Selman, M. F. Petit-Glatron, and R. Chambert. 1995. Isolation and enzymic properties of levansucrase secreted by Acetobacter diazotrophicus SRT4, a bacterium associated with sugar cane. Biochem. J. 309:113-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez, L., M. Sotolongo, Y. Rosabal, C. Menendez, R. Ramirez, J. Caballero-Mellado, and J. Arrieta. 2000. Structural levansucrase gene (lsdA) constitutes a functional locus conserved in the species Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus. Arch. Microbiol. 174:120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hettwer, U., F. R. Jaeckel, J. Boch, M. Meyer, K. Rudolph, and M. S. Ullrich. 1998. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression in Escherichia coli of levansucrase genes from the plant pathogens Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea and P. syringae pv. phaseolicola. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3180-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang, K. H., J. W. Seo, K. B. Song, C. H. Kim, and S. K. Rhee. 1999. Extracellular secretion of levansucrase from Zymomonas mobilis in Escherichia coli. Bioprocess Eng. 21:453-458. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jimenez-Salgado, T., L. E. Fuentes-Ramirez, A. Tapia-Hernandez, M. A. Mascarua-Esparza, E. Martinez-Romero, and J. Caballero-Mellado. 1997. Coffea arabica L., a new host plant for Acetobacter diazotrophicus, and isolation of other nitrogen-fixing acetobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3676-3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagami, Y., M. Ratliff, M. Surber, A. Martinez, and D. N. Nunn. 1998. Type II protein secretion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: genetic suppression of a conditional mutation in the pilin-like component XcpT by the cytoplasmic component XcpR. Mol. Microbiol. 27:221-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaPointe, C. F., and R. K. Taylor. 2000. The type 4 prepilin peptidases comprise a novel family of aspartic acid proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1502-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, H., and M. S. Ullrich. 2001. Characterization and mutational analysis of three allelic lsc genes encoding levansucrase in Pseudomonas syringae. J. Bacteriol. 183:3282-3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, Y., J. A. Triccas, and T. Ferenci. 1997. A novel levansucrase-levanase gene cluster in Bacillus stearothermophilus ATCC12980. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1353:203-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu, H. M., S. T. Motley, and S. Lory. 1997. Interactions of the components of the general secretion pathway: role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilin subunits in complex formation and extracellular protein secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 25:247-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menendez, C., L. Hernandez, G. Selman, M. F. Mendoza, P. Hevia, M. Sotolongo, and J. G. Arrieta. 2002. Molecular cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of an exo-levanase gene from the endophytic bacterium Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus SRT4. Curr. Microbiol. 45:5-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meng, G., and K. Futterer. 2003. Structural framework of fructosyl transfer in Bacillus subtilis levansucrase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:935-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parge, H. E., K. T. Forest, M. J. Hickey, D. A. Christensen, E. D. Getzoff, and J. A. Tainer. 1995. Structure of the fibre-forming protein pilin at 2.6 A resolution. Nature 378:32-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pepe, J. C., and S. Lory. 1998. Amino acid substitutions in PilD, a bifunctional enzyme of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Effect on leader peptidase and N-methyltransferase activities in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 273:19120-19129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pons, T., D. G. Naumoff, C. Martinez-Fleites, and L. Hernandez. 2004. Three acidic residues are at the active site of a beta-propeller architecture in glycoside hydrolase families 32, 43, 62, and 68. Proteins 54:424-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Possot, O., and A. P. Pugsley. 1994. Molecular characterization of PulE, a protein required for pullulanase secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 12:287-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugsley, A. P. 1993. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:50-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pugsley, A. P., N. Bayan, and N. Sauvonnet. 2001. Disulfide bond formation in secreton component PulK provides a possible explanation for the role of DsbA in pullulanase secretion. J. Bacteriol. 183:1312-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rathsam, C., P. M. Giffard, and N. A. Jacques. 1993. The cell-bound fructosyltransferase of Streptococcus salivarius: the carboxyl terminus specifies attachment in a Streptococcus gordonii model system. J. Bacteriol. 175:4520-4527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reese, M. G., N. L. Harris, and F. H. Eeckman. 1996. Large scale sequencing specific neural networks for promoter and splice site recognition, p. 737-738. In L. Hunter and T. E. Klein (ed.), Biocomputing. Proceedings of the 1996 Pacific Symposium. World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore.

- 36.Saito, K., A. Yokota, and F. Tomita. 1997. Molecular cloning of levan fructotransferase gene from Arthrobacter nicotinovorans GS-9 and its expression in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 61:2076-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Sandkvist, M. 2001. Biology of type II secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 40:271-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandkvist, M. 2001. Type II secretion and pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 69:3523-3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song, K. B., H. K. Joo, and S. K. Rhee. 1993. Nucleotide sequence of levansucrase gene (levU) of Zymomonas mobilis ZM1 (ATCC10988). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1173:320-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song, K. B., J. W. Seo, M. G. Kim, and S. K. Rhee. 1998. Levansucrase of Rahnella aquatilis ATCC33071. Gene cloning, expression, and levan formation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 864:506-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinmetz, M., D. Le Coq, S. Aymerich, G. Gonzy-Treboul, and P. Gay. 1985. The DNA sequence of the gene for the secreted Bacillus subtilis enzyme levansucrase and its genetic control sites. Mol. Gen. Genet. 200:220-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strom, M. S., P. Bergman, and S. Lory. 1993. Identification of active-site cysteines in the conserved domain of PilD, the bifunctional type IV pilin leader peptidase/N-methyltransferase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 268:15788-15794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tajima, K., T. Tanio, Y. Kobayashi, H. Kohno, M. Fujiwara, T. Shiba, T. Erata, M. Munekata, and M. Takai. 2000. Cloning and sequencing of the levansucrase gene from Acetobacter xylinum NCI 1005. DNA Res. 7:237-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang, L. B., R. Lenstra, T. V. Borchert, and V. Nagarajan. 1990. Isolation and characterization of levansucrase-encoding gene from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Gene 96:89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tapia-Hernandez, A., M. R. Bustillos-Cristales, T. Jimenez-Salgado, J. Caballero-Mellado, and L. E. Fuentes-Ramirez. 2000. Natural endophytic occurrence of Acetobacter diazotrophicus in pineapple plants. Microb. Ecol. 39:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Hijum, S. A., E. Szalowska, M. J. van der Maarel, and L. Dijkhuizen. 2004. Biochemical and molecular characterization of a levansucrase from Lactobacillus reuteri. Microbiology 150:621-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1982. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vignon, G., R. Kohler, E. Larquet, S. Giroux, M. C. Prevost, P. Roux, and A. P. Pugsley. 2003. Type IV-like pili formed by the type II secreton: specificity, composition, bundling, polar localization, and surface presentation of peptides. J. Bacteriol. 185:3416-3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voulhoux, R., G. Ball, B. Ize, M. L. Vasil, A. Lazdunski, L. F. Wu, and A. Filloux. 2001. Involvement of the twin-arginine translocation system in protein secretion via the type II pathway. EMBO J. 20:6735-6741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker, J. E., M. Saraste, M. J. Runswick, and N. J. Gay. 1982. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1:945-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]