Abstract

Background & Aims

Anti-depressants are frequently prescribed to treat functional dyspepsia (FD), a common disorder characterized by upper abdominal symptoms, including discomfort or post-prandial fullness. However, there is little evidence for the efficacy of these drugs in patients with FD. We performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the effects of anti-depressant therapy effects on symptoms, gastric emptying (GE), and mealinduced satiety in patients with FD.

Methods

We performed a study at 8 North American sites of patients who met the Rome II criteria for FD and did not have depression or use anti-depressants. Subjects (n=292; 44±15 y old, 75% female, 70% with dysmotility-like FD, and 30% with ulcer-like FD) were randomly assigned to groups given placebo, 50 mg amitriptyline, or 10 mg escitalopram for 10 weeks. The primary endpoint was adequate relief of FD symptoms for ≥5 weeks of the last 10 weeks (out of 12). Secondary endpoints included GE time, maximum tolerated volume in a nutrient drink test, and FD-related quality of life.

Results

An adequate relief response was reported by 39 subjects given placebo (40%), 51 given amitriptyline (53%), and 37 given escitalopram (38%) (P=.05, following treatment, adjusted for baseline balancing factors including all subjects). Subjects with ulcer-like FD given amitriptyline were more than 3-fold more likely to report adequate relief than those given placebo (odds ratio=3.1; 95% confidence interval, 1.1–9.0). Neither amitriptyline nor escitalopram appeared to affect GE or meal-induced satiety after the 10 week period in any group. Subjects with delayed GE were less likely to report adequate relief than subjects with normal GE (odds ratio=0.4; 95% confidence interval, 0.2–0.8). Both anti-depressants improved overall quality-of-life.

Conclusions

Amitriptyline, but not escitalopram, appears to benefit some patients with FD— particularly those with ulcer-like (painful) FD. Patients with delayed GE do not respond to these drugs.

Keywords: Functional dyspepsia, abdominal pain, functional gastrointestinal disorder, antidepressant

INTRODUCTION

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by upper abdominal discomfort or pain, and symptoms of meal-related fullness or satiety.1 The condition has symptom similarities with other conditions including gastroesophageal reflux, peptic ulcer disease, or irritable bowel syndrome. However, dyspepsia symptoms typically do not improve with proton pump inhibitor therapy and are not chronologically associated with bowel habits. The pathogenesis remains unclear, but abnormalities in gastric motor and sensory function and more recently low grade duodenal inflammation have been identified.2, 3 Research studies have shown that diagnosing FD can be difficult. Diagnostic testing usually includes upper endoscopy as well as testing for H. pylori. FD symptoms often interfere with school and work, and weight loss may occur due to dietary restrictions.4–7

FD symptom management remains challenging. Treatment may include dietary modifications, anti-emetics, antispasmodics, prokinetics and analgesics.8 Thus, options are quite varied, and applied based on predominant symptom. Although antidepressants—including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)9—have been used for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), their efficacy in FD management is very uncertain. Antidepressant data in FD are limited to four smaller studies utilizing amitriptyline, venlafaxine, and sertraline.10–13 It is postulated that antidepressants may be efficacious through reduction of psychological symptoms (e.g. anxiety or depression), central analgesic actions14 or reduction of affective arousal and sleep restoration.15, 16 Both TCAs and SSRIs have been shown to differently alter orocecal transit times and gastric accommodation.17, 18

Despite ongoing clinical use, uncertainty remains regarding antidepressants’ clinical efficacy and mechanism of treatment response in FD. The aim of this multi-center, randomized, placebocontrolled trial was to assess whether 12 weeks of therapy with amitriptyline or escitalopram was more efficacious than placebo in the relief of FD symptoms and in improving quality of life. Our secondary aim was to assess whether gastric emptying and meal-induced satiety were altered by treatment with a TCA or SSRI, and whether changes in gastric physiology were associated with treatment outcome. Further, we aimed to determine if efficacy persisted 6 months after treatment was ceased.

METHODS

Study Overview

This National Institutes of Health (NIH, DK065713) funded, multicenter, randomized, double-blind parallel group trial (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT00248651) comparing 12 weeks of amitriptyline, escitalopram, and matching placebo pills is summarized in Figure 1. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each site. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. Mayo Clinic Rochester monitored each site, centralized data storage, and analyzed the data. Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) and NIH members monitored the study bimonthly and monthly, respectively. The trial design has been reported previously.19 Only results of the clinical primary aims will be reported. After trial commencement, to facilitate recruitment, the study was changed from five sites to nine sites to facilitate recruitment. No changes in trial outcomes were made. The study ended based on funding period. All authors had access to the study data, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

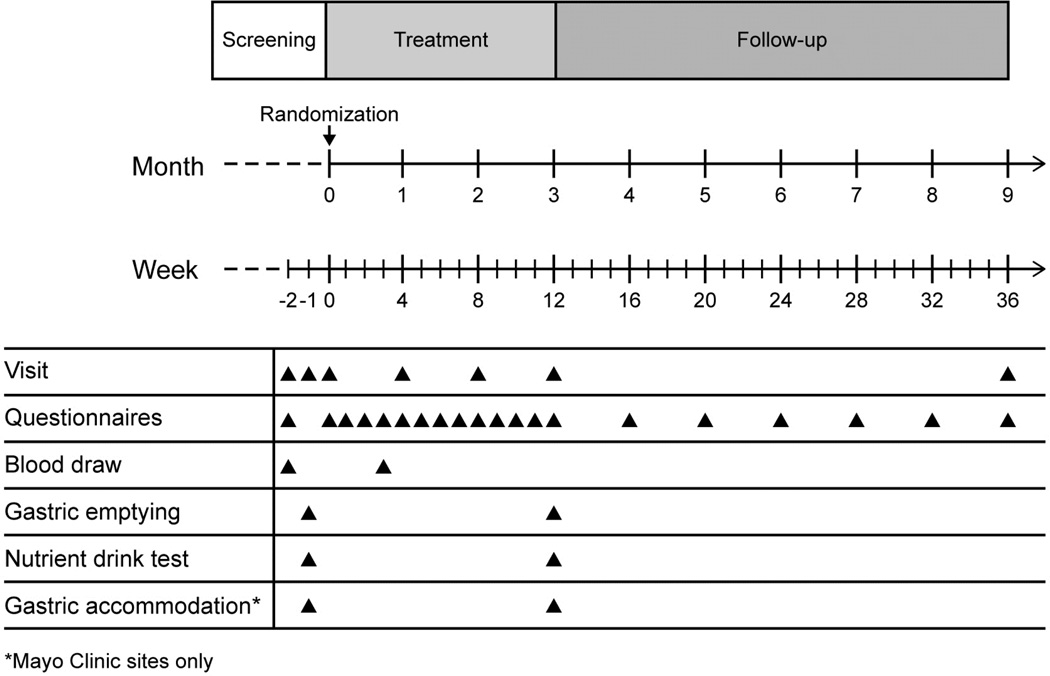

Figure 1. Study Design.

There was a screening period of 0–4 weeks before randomization on day 1. Two on-site visits were required prior to randomization, with a third visit if a gastric accommodation study was performed (Mayo Clinic sites only). Study visits were monthly during the treatment phase. Weekly assessments were performed by phone during the treatment period, and then monthly during the follow up period.

Study Participants

Enrollment was during October 2006 through October 2012. The last patient was randomized November 2012 and completed 6 month post-treatment follow up August 2013. Inclusion criteria were age 18–75 years, Rome II criteria for FD (Table 1),20 and a normal upper endoscopy within five years. FD subtype was determined from a structured interview conducted at the baseline visit, and then defined as ulcer-like or dysmotility-like. If the participant had not had an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) within 5 years, one was performed prior to randomization in our trial. Exclusion criteria were symptom resolution with antisecretory therapy (PPI use for other reasons that did not resolve FD symptoms were allowed), current antidepressant or NSAID use, history of esophagitis or ulcer disease or other organic upper gastrointestinal disease, current drug or alcohol abuse, current or planned pregnancy, major abdominal surgery, or major physical illness. Individuals with a Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) score ≥11 on the depression scale were excluded. Subjects over age 50 years underwent an electrocardiogram. Women of childbearing years were administered a urine pregnancy test. Each site-specific investigator or coordinator recruited and enrolled participants.

Table 1.

Rome II Diagnostic Criteria for Functional Dyspepsia20

| Functional dyspepsia: | Subtypes: |

|---|---|

At least 12 weeks, which need not be consecutive, within the preceding 12 months of:

|

Ulcer-like dyspepsia Pain centered in the upper abdomen is the predominant (most bothersome) symptom. |

|

Dysmotility-like dyspepsia An unpleasant or troublesome non-painful sensation (discomfort) centered in the upper abdomen is the predominant symptom. | |

| This sensation may be characterized by or associated with upper abdominal fullness, early satiety, bloating, or nausea. |

Baseline Washout

Subjects had a two to four week baseline assessment period before randomization based on patient, staff and research equipment availability for study testing. Validated symptom diaries were completed during this period.21 Subjects were required to have at least moderate FD symptoms on the validated GI Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS, a score of ≥3) for at least four days during a two-week period.

Randomization and Blinding

Dynamic allocation randomization was used whereby treatment assignment was based on the distribution across balancing factors for previous assignments. The randomization allocation schedule was created by the Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics at Mayo Clinic. Treatment assignment was to the smallest group with specific combinations of balancing factors. Balancing factors were sex, body mass index (BMI), race, anxiety, dyspepsia subtype, gastric emptying, meal-induced satiety, and recruitment site. Concealed allocation was assured by use of a central web-based system. A double dummy design was implemented for subject and study personnel blinding. Blinded assessors collected outcome data; subjects were instructed not to mention side effects to the assessor.

Treatment Arms

There were three treatment arms: placebo (PLA: amitriptyline placebo/escitalopram placebo), amitriptyline (AMI: 50 mg amitriptyline/escitalopram placebo), or escitalopram (ESC: amitriptyline placebo/10mg escitalopram). Pills were administered in blister packs for single nightly dosing before bed time. To minimize side effects, subjects randomized to amitriptyline received 25 mg (identical to the 50 mg dose) for the first two weeks. Amitriptyline and matching placebo were compounded by the Mayo Clinic Research Pharmacy. Escitalopram and matching placebo were provided by Forest Pharmaceuticals.

Study Questionnaires

Weekly global symptom assessment was measured through “Adequate relief” of dyspepsia symptoms during the prior week.22, 23 This self-report measure is considered clinically relevant and has been tested for responsiveness in FD.24, 25 The disease-specific validated Nepean Dyspepsia Index (NDI) was used to assess FD quality-of-life26 at baseline and post-treatment. NDI scores are summarized into overall quality of life and 5 subscales: Interference, Knowledge/Control, Eating/Drinking, Sleep Disturbance, Work/Study (range 0–100).27 Validated daily symptom diaries assessing upper abdominal pain, nausea, bloating, fullness, and early satiety on a scale of 0–3 (0, nil; 1 mild; 2 moderate; 3 severe) were also collected.21

GI Physiology Tests

Scintigraphy-based solid-phase gastric emptying study was performed in all participants at baseline and treatment end. It was completed in the morning after an overnight fast using a standard meal (99mTc-labeled meal consisting of two scrambled eggs, one slice whole wheat bread, and one glass of skim milk) with acquisition of measurements at 0, 1, 2, and 4 hours.28 All scans were read at one site. Delayed gastric emptying was defined as <84% emptying at 4 hours.29 Reproducibility, performance characteristics and coefficient of variation have been extensively studied.30

Nutrient drink test (NDT) for meal-induced satiety was performed in all participants. NDT had subjects drink 120 ml of ENSURE® every four minutes.31 Satiety scores were measured on a scale graded 0–5 (1, no symptoms; 5, maximum satiety). When a score of 5 was reached, the maximum tolerated volume (MTV) intake was measured. Subjects scored their symptoms (pain, fullness, bloating, nausea) using a 100 mm visual analog scale 30 minutes after completing the test, and an aggregate score was calculated as a sum of the four symptom scores (range: 0–100). Abnormal satiety was defined as inability to consume >800 ml of Ensure®.32

Efficacy Endpoints

The a priori primary endpoint was defined as self-report of adequate relief (yes/no) for at least 50% of weeks 3–12 of treatment (10 weeks). The first two weeks of treatment were excluded to allow for establishment of steady state drug levels. Pre-specified secondary endpoints were t1/2 for the gastric emptying study, MTV to full satiation, satiety aggregate symptom score at 30 minutes, and NDI scores.

Compliance

Study compliance including study medication use was ensured by monitoring completion of questionnaires and pharmacy logs. A subset (n=161, 55%) had drug levels checked at week 4.

Follow-up at 6 months

Evaluations were conducted each month for 6 months off therapy. Symptom assessment and FD medication use was measured. Relapse was defined by “No” to the query regarding adequate response and/or use of an antidepressant or proton pump inhibitor or histamine-2 receptor blocker.

Statistical Analysis

An Intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis included all randomized subjects (97 PLA, 97 AMI, 98 ESC). Symptom relief was evaluated for treatment effects using a logistic regression model with adequate relief as the binary dependent variable. At least 5 weeks (of 10) of symptom relief were required to be considered a responder. The model coefficients were used to estimate the odds for adequate relief in the active treatment groups (relative to the placebo group) adjusting for randomization covariates (sex, body mass index [BMI], race, anxiety, dyspepsia subtype, gastric emptying, meal-induced satiety, and recruitment site) in the multiple variable model. To ensure balance on the number of important covariates we used a dynamic allocation randomization method. The dynamic allocation procedure works by ensuring that, as accrual proceeds, no imbalance occurs along the marginal distributions of the stratification factors across treatment arms and the number of categories of stratification factor combinations cannot exceed one half of the treatment group sample size (i.e. n/2).33, 34 Missing data on other continuous endpoints was imputed using the overall mean of the corresponding non-missing endpoint data. An adjustment in the error degrees of freedom (df) in the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models (subtracting one df for each missing value imputed) was used to obtain a more accurate estimate of the residual error variance.

To evaluate whether there were subgroups that were associated with better antidepressant response, additional a priori analyses were examined evaluating FD subtype, gastric emptying, and meal-induced satiety, by incorporating specific interaction terms in separate logistic regression models. The effect of treatment on gastric emptying was assessed using an ANCOVA model incorporating the treatment balancing factors and baseline gastric emptying summary as covariates. A similar analysis of the MTV and the aggregate symptom score in each subject was examined.

The above analyses were pre-specified at study design. To evaluate treatment effects on specific symptoms from the daily diary, an ITT analysis was also used based on ANCOVA models incorporating balancing factors and the baseline (run-in period) scores. All analyses were done using SAS® statistical software version 9.3 (Cary, NC). A blinded interim analysis was done for the DSMB (but not shared with investigators) in December of 2010. A p-value of <0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample Size

For the primary outcome of adequate relief, assuming a 20%, 25%, 30%, and 35% placebo response rate and a 20% therapeutic gain over placebo to be clinically significant, the N per group required would be 98, 107, 113, and 116, respectively, to achieve ~80% power at a two-sided alpha level of 0·025 (i.e. adjusting for two pair-wise tests, each active drug against placebo). We assumed a 25% drop out rate in each arm. The planned recruitment was for 133–134 per arm (400 total).

Using the observed variation in non-missing gastric emptying t1/2, a two-sample t-test at α=0·025 (i.e. adjusted for two pair-wise comparisons) would have had ~80% power to detect a difference between treatment groups of 18 minutes assuming a sample size of 98 per arm. Using the observed non-missing data for the NDT, a sample size of 98, would have provided ~80% power to detect a difference of 172 ml (21% relative to the overall mean) in MTV and a difference of 37 (24% relative to the overall mean) in the aggregate symptom score.

Role of the Funding Source

The NIH was involved in study design and data interpretation. Forest Pharmaceuticals only provided escitalopram and placebo, and was not involved in the study design, data collection or interpretation, writing the report or the decision to submit. Dr. Talley had full access to the study data and has final responsibility for publication.

RESULTS

Subjects

Overall 399 FD patients were screened at eight sites (Figure 2). A total of 341 individuals met eligibility criteria and 292 subjects (97 PLA, 97 AMI, and 98 ESC) were randomized. Sample demographic and physiologic characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The mean age was 44 years, 219 (75%) were female, and 250 (86%) were Caucasian. A total of 289 (99%) had documented endoscopy data within 5 years of recruitment; 231 (80%) had an endoscopy within a year of recruitment. The median time between endoscopy and recruitment was 10 months (range: 6 days to 4.9 years). A total of 40 (of 282 tested, 14%) were serologically positive for H. pylori antibodies. Prior cholecystectomy was uncommon (n=26, 9%).

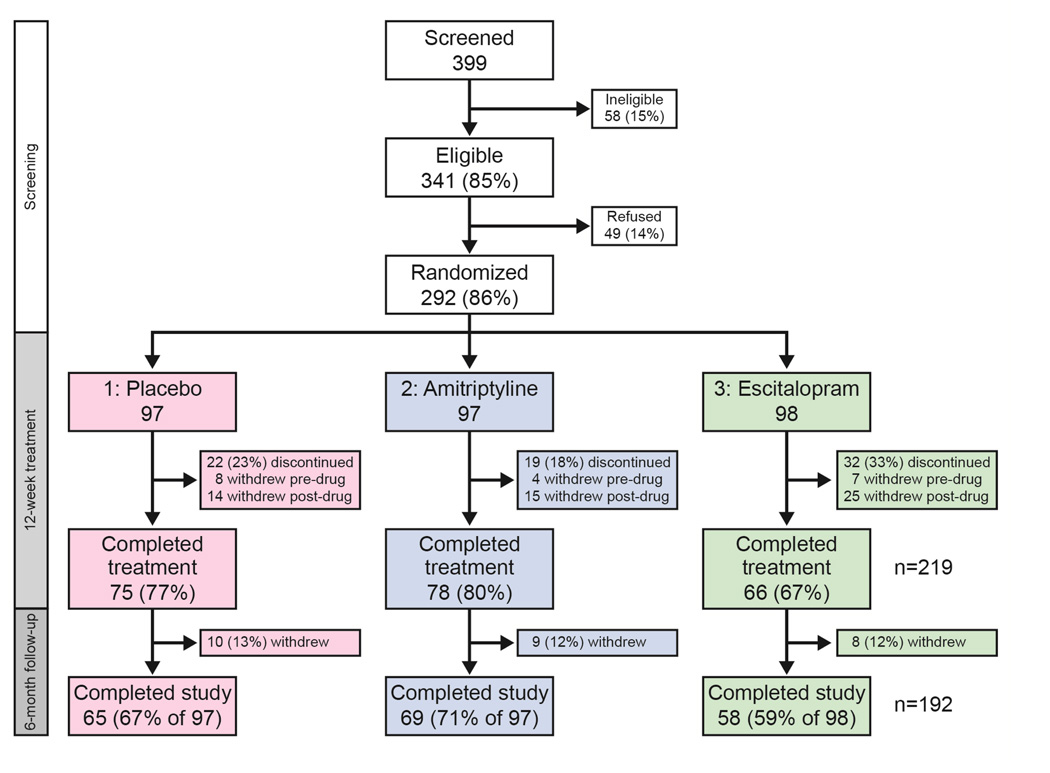

Figure 2. Screening, Randomization, and Follow-up.

After screening the ineligible and unwilling, 292 were randomized to one of three treatment arms, with 224 (77%) completing the Treatment phase. 292 were included in the Intention-To-Treat (ITT) analysis; 205 were included in the Per-Protocol analysis.

Table 2.

Subject Characteristics, n=292

| PLA n=97 |

AMI n=97 |

ESC n=98 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 45 (16) | 43 (15) | 45 (15) |

| Female, n (%) | 73 (75%) | 72 (74%) | 74 (76%) |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 83 (86%) | 82 (85%) | 85 (87%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.4 (5.2) | 25.7 (6.0) | 26.1 (5.6) |

| HADS score, mean(SD) | |||

| HADS depression | 3.1 (2.9) | 3.1 (2.7) | 3.1 (2.7) |

| HADS anxiety | 5.0 (3.8) | 5.2 (3.2) | 5.4 (3.8) |

| Dyspepsia subtype | |||

| Dysmotility-like, n (%) | 69 (71%) | 67 (69%) | 68 (69%) |

| Ulcer-like, n (%) | 28 (29%) | 30 (31%) | 30 (31%) |

| Delayed gastric emptying, n (%) | 20 (21%) | 20 (21%) | 21 (21%) |

| Abnormal satiety, n (%) | 55 (57%) | 55 (57%) | 55 (56%) |

| H. pylori antibody positive, n (%) | 9/92 (10%) | 14/96 (15%) | 17/94 (18%) |

| Baseline PPI use, n (%) | 18 (19%) | 27 (28%) | 23(23%) |

PLA: Placebo; AMI: Amitriptyline; ESC: Escitalopram; HADS: Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale; PPI: Proton Pump Inhibitor

Overall, 204 (70%) had dysmotility-like FD and 88 (30%) had ulcer-like FD, while 61(21%) had delayed baseline gastric emptying and 165 (57%) had abnormal meal-induced satiety. Of those with dysmotility-like FD (n=204), 44 (22%) had delayed gastric emptying and 116 (57%) had an abnormal satiety test; of those with ulcer-like FD (n=88), 17 (19%) had delayed gastric emptying and 49 (57%) had an abnormal satiety test. Sixty two (21%) also met criteria for IBS: 25 (41%) IBS-C, 20 (33%) IBS-D, 6 (10%) IBS-M, and 11 (18%) undifferentiated IBS. The association of FD alone vs. FD-IBS overlap, was not significant for age (median: 43 v. 48 years, p=0.96), or gender (27% v 18%% female, p=0.13).

Of the 292, 219 (75%) subjects completed the 12 week treatment trial and 192 (65% of 292) individuals participated through the 6 month follow up period. Among those completing treatment, the number of pills taken was similar among the three arms: median (range) of 168 (80–186) PLA, 168 (92–186) AMI, and 168 (68–186) ESC of 186 maximum. Of those with drug levels checked, 58 of 81 (72%) in the AMI arm and 58 of 76 (76%) in the ESC arm had detectable drug levels at week 4.

Adequate Relief

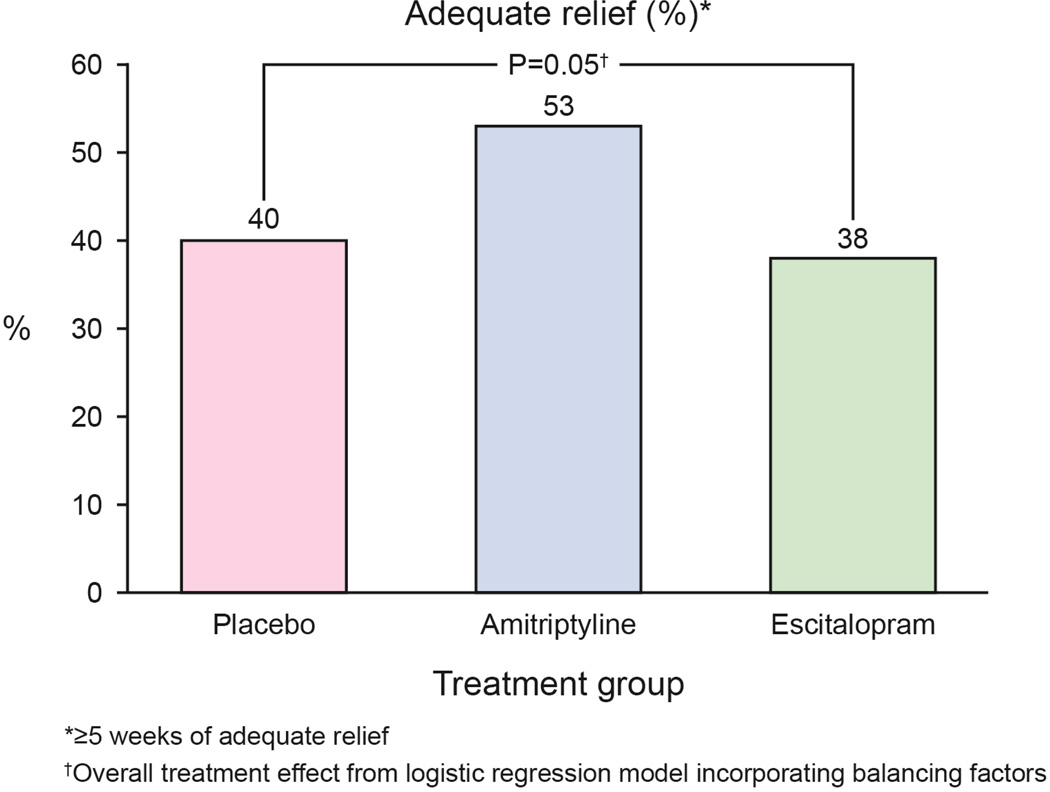

In the ITT analysis, the rates for adequate relief were 39 (40%) for placebo, 51 (53%) for amitriptyline and 38 (38%) for escitalopram (Figure 3A), indicating a difference (p=0.05) between the three treatment arms. In treatment arm v. treatment arm comparisons, those receiving amitriptyline appeared to respond better than placebo (p=0.07, OR =1.1 [95% CI: 0.6–2.1]) whereas escitalopram was comparable to placebo (p=0.65). The odds ratios for the pairwise comparisons are shown in Figure 4.

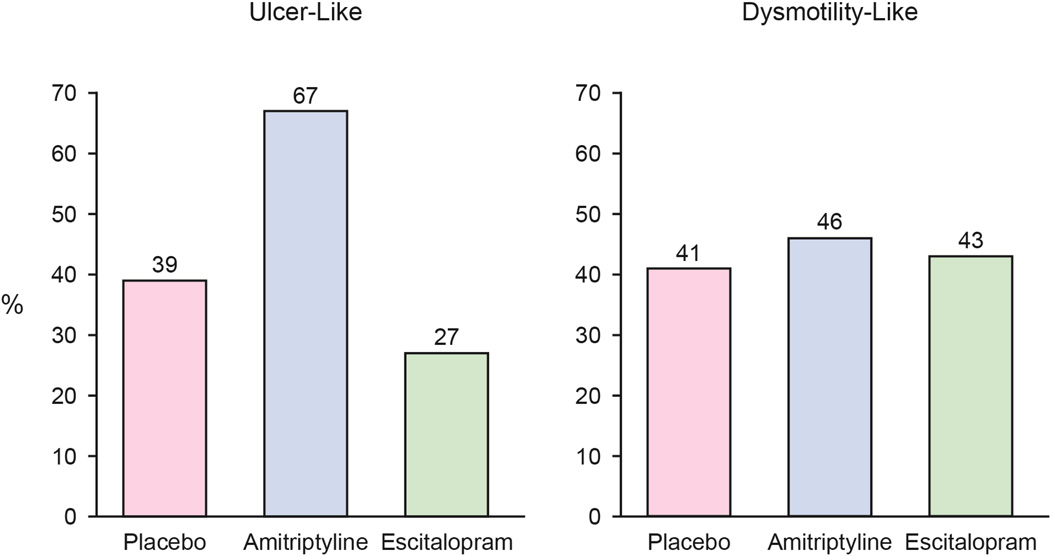

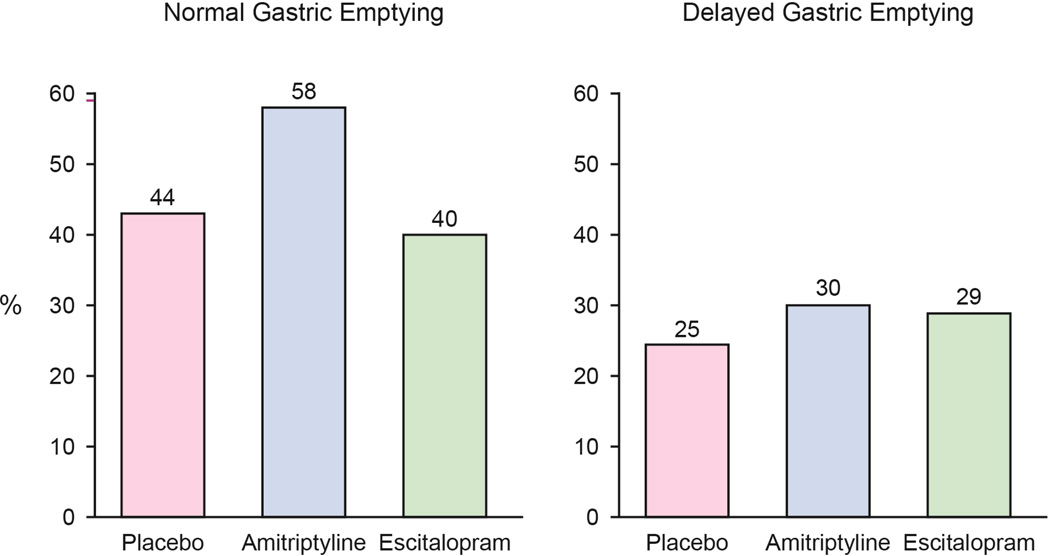

Figure 3. Primary End point: Adequate Relief.

A. Adequate relief of overall FD symptoms were reported by 39 (40%) in the placebo arm, 51 (53%) in the amitriptyline arm, and 38 (38%) in the escitalopram arm.

B. Patient with ulcer-like FD had higher reports of adequate relief of FD symptoms in those receiving amitriptyline.

C. Patients with dysmotility-like FD did not respond differently between the three treatment arms.

D. Among subjects with normal gastric emptying at baseline, adequate relief was reported by 34 (44%) in the placebo arm, 45 (58%) in the amitriptyline arm, 31 (40%) in the escitalopram arm.

E. Among subjects with delayed gastric emptying at baseline, adequate relief was reported by 5 (25%) in the placebo arm, 6 (30%) in the amitriptyline arm, and 6 (29%) in the escitalopram arm. Delayed gastric emptying was defined as <84% emptying at 4 hours.

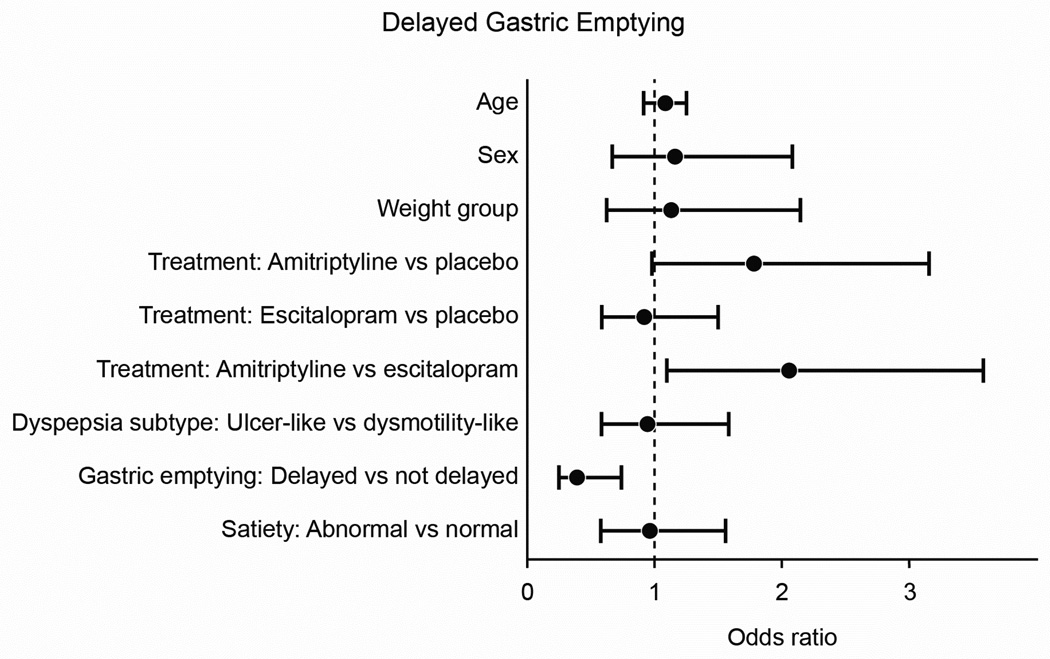

Figure 4. Odds ratios for Adequate Relief.

By pairwise comparisons, the amitriptyline group had a greater odds of adequate relief than the escitalopram group. Those with delayed gastric emptying had a lower odds of adequate relief compared to those with normal gastric emptying. Age: 10 year increments. Sex: Female vs. Male. HADS anxiety: 2 points. Weight group: Obese vs. Non-Obese. FD subtype: Ulcer-Like vs. Dysmotility-Like. Gastric Emptying: Delayed vs. Non-Delayed. Meal-Induced Satiety: Abnormal vs. Normal.

In ulcer-like FD, subjects receiving amitriptyline reported more adequate relief of FD symptoms than those receiving placebo or escitalopram (11 [39%] PLA vs. 20 [67%] AMI vs. 8 [27%] ESC, p=0.06 interaction term) (Figure 3B, 3C). Those with ulcer-like FD receiving amitriptyline had three-fold greater odds of reporting adequate relief compared to placebo (OR=3.1 [95% CI: 1.1–9.0]). Treatment response was otherwise similar among the three treatment arms in those with dysmotility-like FD (28 [41%] PLA, 31 [46%] AMI, 29 [43%] ESC). Age, sex, BMI, and baseline HADS scores were not associated with differential treatment response. Those with both FD and IBS were equally likely to respond to amitriptyline as those with FD alone (test for interaction p=1.0). There was a borderline differential treatment effect (p=0.08) in the small number of FD patients with a prior cholecystectomy compared to those without a prior cholecystectomy with better treatment response among those with prior cholecystectomy.

In a per protocol analysis (n=205), response rates were highest in the amitriptyline arm: 38 (52%) for placebo, 47 (66%) for amitriptyline, and 32 (52%) for escitalopram (p=0.09). Subjects receiving amitriptyline had a greater odds for adequate relief than those receiving placebo (OR=2.1 [95% CI:1.04–4.36], p=0.04).

Gastric Emptying

Mean t1/2 for gastric emptying at baseline was similar among the three groups (112 [SD=38] PLA vs. 117 [SD=44] AMI vs. 120 [SD=46] ESC). No differences in post-treatment t1/2 values among the three treatment arms was observed (115 [SD=40] PLA vs. 117 [SD=43] AMI vs. 108 [SD=36] ESC) (Supplement Figure 1). Those with delayed gastric emptying at baseline had lower odds of reporting adequate relief than subjects with normal gastric emptying (OR=0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.8). The test for interaction between gastric emptying status and treatment group on response to therapy was not significant (p=0.68) (Figure 3D, 3E).

Nutrient Drink Test

All treatment arms had similar baseline MTV (752 [SD 347] PLA vs. 708 [SD 371] AMI vs. 755 [SD 368] ESC) and baseline aggregate symptom scores (173 [SD 84] PLA vs. 196 [SD 87] AMI vs. 189 [SD 82] ESC). After treatment, MTV did not differ by treatment (839 [SD 442] PLA vs. 764 [SD 319] AMI vs. 823 [SD 391] ESC) (Supplement Figure 2). Post-drink aggregate and individual (nausea, fullness, bloating, abdominal pain) symptom scores did not differ by treatment arm. Postprandial symptom results did not differ by FD subgroup (all interaction tests ≥ 0.15). Tests to evaluate whether baseline satiety predicted response to therapy were not significant. Formal tests for differential treatment effects on MTV depending on FD subtype (p=0.09 for interaction effects) suggested that subjects with dysmotility-like FD had lower volumes among those treated with amitriptyline (vs. placebo); while in the ulcer-like FD subgroup, lower volumes were observed in those treated with escitalopram (vs. placebo).

Daily Diary Symptoms

Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and deltas for daily diary scores by treatment arm are summarized in Table 3. No differential treatment effects were seen for upper abdominal pain, nausea, or bloating. However, there were modest treatment effects favoring amitriptyline for fullness (p=0.03) and early satiety (p=0.07). FD subtype was not a predictor of symptom response for any of the five symptom scores.

Table 3.

Daily Diary Scores and Nepean Dyspepsia Index (NDI) FD-specific quality-of-life, mean (95% CI)

| BASELINE | POST-TREATMENT | Δ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLACEBO | |||

| Diary | |||

| a. Upper abdominal pain | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | −0.4 (−0.6 – −0.2) |

| b. Nausea | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | −0.4 (−0.6 – −0.2) |

| c. Bloating | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | −0.3 (−0.5 – −0.2) |

| d. Fullness | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | −0.4 (−0.6 – −0.2) |

| e. Early Satiety | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | −0.4 (−0.6 – −0.2) |

| NDI Overall Quality of Life | 63.6 (58.9–68.2) | 73.5 (69.1–77.8) | 9.9 (5.7–14.1) |

| a. Interference | 68.0 (62.8–73.1) | 76.2 (70.9–81.5) | 8.2 (3.6–12.9) |

| b. Knowledge/control | 62.9 (58.1–67.8) | 72.9 (68.2–77.6) | 10.0 (5.8–14.2) |

| c. Eat/drink | 52.2 (45.6–58.9) | 64.8 (59.6–70.1) | 12.6 (6.8–18.4) |

| d. Sleep disturbance | 67.3 (60.8–73.8) | 76.4 (70.9–81.8) | 9.0 (3.5–14.6) |

| e. Work/study | 68.8 (63.0–74.6) | 79.7 (74.5–84.9) | 10.9 (5.3–16.6) |

| NDI Mean Symptom Score | 8.5 (8.1–9.0) | 9.6 (9.2–10.0) | 1.1 (0.7–1.4) |

| a. Abdominal pain | 32.2 (29.9–34.4) | 36.3 (34.0–38.6) | 4.2 (2.2–6.2) |

| b. Postprandial distress | 13.6 (12.0–15.3) | 15.8 (14.2–17.4) | 2.2 (1.0–3.3) |

| AMITRIPTYLINE | |||

| Diary | |||

| a. Upper abdominal pain | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | −0.6 (−0.8 – −0.4) |

| b. Nausea | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | −0.5 (−0.7 – −0.3) |

| c. Bloating | 1.7 (1.5–1.9) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | −0.4 (−0.6 – −0.2) |

| d. Fullness | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | −0.7 (−0.8 – −0.5) |

| e. Early Satiety | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | −0.6 (−0.8 – −0.4) |

| NDI Overall Quality of Life | 63.7 (59.0–68.3) | 80.6 (76.2–85.0) | 16.9 (12.3–21.6) |

| a. Interference | 69.5 (64.5–74.5) | 83.2 (78.3–88.2) | 13.7 (8.8–18.6) |

| b. Knowledge/control | 62.4 (57.4–67.4) | 78.2 73.2–83.2) | 15.8 (10.9–20.8) |

| c. Eat/drink | 49.1 (43.0–55.2) | 72.4 (66.7–78.0) | 23.3 (16.9–29.7) |

| d. Sleep disturbance | 67.6 (61.2–74.1) | 86.3 (81.6–91.0) | 18.7 (12.2–25.2) |

| e. Work/study | 70.1 (64.6–75.5) | 86.9 (82.6–91.1) | 16.7 (11.9–21.7) |

| NDI Mean Symptom Score | 8.0 (7.6–8.5) | 9.8 (9.3–10.2) | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) |

| a. Abdominal pain | 29.4 (27.3–31.6) | 38.0 (35.6–40.4) | 8.6 (5.9–11.3) |

| b. Postprandial distress | 12.8 (11.3–14.4) | 17.5 (16.0–18.9) | 4.7 (3.1–6.2) |

| ESCITALOPRAM | |||

| Diary | |||

| a. Upper abdominal pain | 1.7 (1.6–1.9) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | −0.4 (−0.5 – −0.2) |

| b. Nausea | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | −0.2 (−0.4 – −0.0 |

| c. Bloating | 1.8 (1.6–2.0) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | −0.4 (−0.6 – −0.2) |

| d. Fullness | 1.7 (1.4–1.9) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | −0.4 (−0.6 – −0.2) |

| e. Early Satiety | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3 | −0.3 (−0.5 – −0.1) |

| NDI Overall Quality of Life | 72.2 (67.1–77.3) | 82.8 (78.4–87.1) | 10.6 (5.5–15.6) |

| a. Interference | 72.2 (67.1–77.3) | 82.8 (78.4–87.1) | 10.6 (5.5–15.6) |

| b. Knowledge/control | 63.4 (58.2–68.6) | 76.2 (71.3–81.1) | 12.8 (7.6–18.0) |

| c. Eat/drink | 53.3 (47.3–59.3) | 70.6 (65.4–75.6) | 17.3 (11.3–23.3) |

| d. Sleep disturbance | 73.6 (67.9–79.2) | 80.8 (75.2–86.3) | 7.2 (1.6–12.8) |

| e. Work/study | 75.3 (69.9–80.8) | 87.2 (83.5–90.9) | 11.9 (6.4–17.3) |

| NDI Mean Symptom Score | 8.4 (7.9–8.9) | 9.7 (9.3–10.2) | 1.3 (0.8–1.8) |

| a. Abdominal pain | 31.6 (29.2–34.1) | 37.1 (34.8–39.4) | 5.5 (3.0–8.0) |

| b. Postprandial distress | 13.1 (11.6–14.6) | 16.7 (15.1–18.4) | 3.6 (2.1–5.1) |

Dyspepsia-specific Quality of Life

Baseline NDI scores for overall quality of life and the five subscales were similar among treatment arms. After treatment, quality of life scores increased in all three arms, indicating improvement in quality of life (Table 3). Both antidepressant arms had higher post-treatment quality of life scores compared to placebo with respect to overall quality of life score (p=0.02), as well as for Eat/Drink (p=0.06), Interference (p=0.06), Sleep Disturbance (p=0.01), and Work/Study (p=0.04). Neither antidepressant fared better than placebo regarding Knowledge/Control. Greater improvements in overall and sleep-related quality of life scores were seen among those with ulcer-like FD receiving amitriptyline (test for interactions, p=0.01 and 0.03, respectively). Better upper abdominal pain and post-prandial distress scores were also seen in those with non-delayed gastric emptying receiving amitriptyline (test for interactions, p=0.03 and p=0.08, respectively).

6 Month Follow-Up Data

Among the 123 with follow-up data in the 127 who met criteria for a responder during the active treatment phase, 90 of 123 (73%) relapsed within 6 months. By treatment group, there were 26 relapses among 38 responders in the placebo arm, 40 relapses in 51 responders in the amitriptyline arm, and 24 relapses in 34 responders in the escitalopram arm (p=0.31).

Safety

235 adverse events were reported by 77 (26%) individuals: 20 (21%) on placebo, 29 (30%) on amitriptyline, 28 (29%) on escitalopram (p>0.05) (Supplement Table 1). No serious adverse events were reported. Five individuals reported five events with a severity of 3 (of 4): very nervous at week 4 (PLA); worsening abdominal pain at week 5 not felt to be study drug-related but resulted in study discontinuation (AMI); suicidal thoughts thought to be related to drug (AMI) that resulted in discontinuation of study drug and resolved after stopping; stomach ache not felt to be related to study drug (ESC); and chest pain two months post-treatment (ESC). Dizziness was more common in the antidepressant arms (p=0.01); drowsiness/somnolence was borderline associated with antidepressants (p=0.09).

DISCUSSION

Because the pathophysiology of FD remains poorly understood and a variety of treatment classes are available, health care providers do face uncertainty in selecting therapies for patients with FD. Options used in practice with limited or no data include antispasmodics, analgesics, over-the-counter remedies, as well as antidepressants to treat visceral hypersensitivity.8 This multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing placebo, amitriptyline, and escitalopram in FD subjects lends support to the use of TCAs—but not SSRIs—for this common disorder. Those receiving amitriptyline had a two-fold increased odds of reporting adequate relief than those receiving escitalopram. The improvement in FD symptoms did not directly correlate with baseline gastric physiology or changes in gastric emptying or satiation.

Amitriptyline appears to derive its benefit predominantly through improving abdominal pain. Despite the smaller number of ulcer-like FD subjects, those with ulcer-like FD receiving amitriptyline were three-fold more likely to report symptom relief than placebo, without similar findings in those with dysmotility-like FD. This is consistent with studies showing amitriptyline is beneficial in pain syndromes including IBS and neuropathic pain.9, 35 This differential treatment effect supports the division of FD into a pain or meal-related satiety subtype. Our findings complement the NORIG trial in which nortriptyline was not helpful in improving idiopathic gastroparesis symptoms including nausea, meal-related satiety, fullness, anorexia, and bloating.36 In our trial, FD patients with normal gastric emptying at baseline treated with amitriptyline reported statistically significant improvement in abdominal pain and post-prandial distress.

Our study suggests that in patients with upper abdominal discomfort with a normal endoscopy, clinicians could usefully subtype the FD based on the Rome criteria. Among individuals with pain-predominant FD, a tricyclic antidepressant may be considered in the management algorithm. Gastric emptying need not be performed unless nausea/vomiting are present and gastroparesis needs to be excluded. Notably FD patients with mild delay in gastric emptying or dysmotility-like FD had only a 30% and 46% response rate to amitriptyline, respectively; a tricyclic antidepressant could be considered in these subsets if depression coexists or if FD-related quality of life is poor. Although bowel irregularity was present in over half of patients with FD, particularly dysmotility-type FD, concurrent IBS was present in only a minority. Treatment response to antidepressant therapy did not differ between patients with FD alone and FD-IBS, suggesting the presence of additional GI symptoms does not decrease the likelihood of response to antidepressant therapy.

Although our study suggests that patients with FD are more likely to respond to tricyclic antidepressants, firm conclusions regarding the role of tricyclic antidepressants in FD management—and specifically its role in management of various FD subtypes and additional outcomes—cannot be made due to the relatively modest sample size and the resulting borderline p-value of 0.05 with the study’s a priori primary endpoint. The limited power was primarily due to difficulty with recruitment. Despite intensive efforts, only 292 were randomized of the planned 400. Identifying individuals with a known diagnosis of FD (and not reflux disease), who did not meet exclusion criteria—including response to antisecretory therapy, current depression or psychiatric disease, or current antidepressant use for any reason, who were willing to participate in this intensive trial—was challenging. It is perhaps debatable whether the study outcome was truly positive. We would argue that the findings are positive in favor of amitriptyline use in FD management because the results appear to follow drug mechanisms with TCAs positively impacting those with painful FD and normal gastric emptying. Furthermore, the mean symptom score on the Nepean Dyspepsia Index improved in those received antidepressants, as did overall FD-related quality of life and specific aspects of FD-specific quality of life improved amongst those receiving antidepressants. Nonetheless, although over half of the FD patients receiving TCAs reported adequate relief of FD symptoms, clearly the remainder did not. In other words, TCAs can help FD symptoms improve, but will not resolve all symptoms in all FD patients.

Side effects were noted in a quarter of the participants, including those on placebo. Although FD patients have reported antidepressant intolerance,37 this study found that the antidepressant side effect experience was quite heterogeneous, although gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms were globally more common on active treatment. However, there were no common gastrointestinal symptoms among treatment groups. Only dizziness was a common neurological symptom, particularly in the escitalopram group. This symptom heterogeneity may reflect underlying sensitivity and vigilance rather than drug-related adverse events. While SSRIs may be perceived to be better tolerated than TCAs, we did not find this.

One potential drawback of the study design is that it includes the requirement of a normal EGD, but only within the past five years, raising the question that individuals with an alternative explanation for symptoms may have been included. Reassuringly, 80% of the participants had an EGD within 1 year of study recruitment. As a prior study has shown that the yield from EGD in functional dyspepsia is low in the absence of alarm features38 and a meta-analysis in FD found that endoscopy was not superior to empiric acid suppression in terms of outcomes, the likelihood of misclassification of FD appears low.39

The greatest strength of this study is that although it may have been slightly underpowered to evaluate FD subgroups, it remains nonetheless one of the largest and most ambitious studies of FD performed to date. Clinical trials evaluating symptom-based functional gastrointestinal disorders can be challenging when a number of endpoints exist (e.g. adequate relief, global symptoms). This study utilized “adequate relief” as its primary outcome, which has been used and accepted in other functional GI trials such as IBS.23, 40 Although Rome III criteria were not applied because the study began prior to their publication, the present data suggest epigastric pain syndrome and ulcer-like dyspepsia cover similar domains. This study’s execution and interpretation of results were regularly overseen by the National Institutes of Health and the Data and Safety Monitoring Board. Although a number of outcomes were collected in this comprehensive study, only pre-designated aims and analyses are reported in this manuscript.

In conclusion, in this large, multicenter, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial, amitriptyline appeared beneficial in FD, particularly in those with ulcer-like FD. Although adverse events were common, there was no overall difference between the three arms (except neurologic symptoms, with highest rates in the escitalopram arm) suggesting that with provider counseling and support, TCAs will be generally well-tolerated at low doses. The results do not support the use of escitalopram in FD.

Supplementary Material

Functional Dyspepsia Treatment Trial Cumulative Protocol Amendments.

There were personnel modifications made throughout the study duration, as needed. The study PI was changed from Dr. Nicholas Talley to Dr. G. Richard Locke, III, in 2010.

H. pylori test changed from a stool collection to a serum blood test

Added patient instruction to avoid the consumption of grapefruit or grapefruit juice while on study medication

Added patient instruction to avoid the use of serotonin enhancing drugs while on study medication

Patients who discontinue any antidepressant as per their prescribing physician will wait 30 days from last dose of antidepressant before study participation

Allowed the use of H2 receptor antagonist and PPI’s

A patient score of ≥11 on the HADS questionnaire will be excluded

Increased inclusion age to 18–75

Further detailed prohibited medications

Changed baseline symptom assessment period from 4 weeks to 2–4 weeks

Increased remuneration for physiological testing

Leftover blood from lab work to be frozen

Updated Nutrient Drink Test symptom scoring to be completed at baseline, satiety, 15 & 30 minutes post satiety

Added exclusion point of excluding patients who have QT prolongation

Gastric emptying scans to be completed at 0, 30 minutes, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h.

Study sites were updated to remove University of Alabama and add Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Baylor College of Medicine, and McMaster University Medical Centre

Gastric Accommodation tests were added at the Mayo Scottsdale and Jacksonville centers

The following patient questionnaires were added throughout the protocol; SCL-90-R, POMS, STAI, PSQI, SSC, SSI, EDE-Q, ETISR-SF, and Drossman Abuse Questionnaire. The CIDI & EPQ were removed

Removed daily symptom diaries during the follow-up phase

Assigned a Safety Officer, to make decisions regarding continued study participation if patient drug values show toxicity

Study title changed from “Antidepressant Therapy for Functional Dyspepsia” to “Functional Dyspepsia Treatment Trial”

Addition of the Executive Committee, further defined Steering Committee

Further detailed retention strategies

Clarifications were completed regarding dropouts and the analysis of this data

A responder will be identified as a study patient who answers “yes” to adequate relief for at least 50%, during the last ten weeks of treatment (Weeks 3–12)

Further defined the covariates of psychiatrics status as a HAD anxiety scale of ≥11, and satiety as ≤ 800 ml as abnormal

Interim analysis was added as per request of the DSMB

Added the genotyping of additional genetic variants

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Grant Support: This study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (DK065713). Forest Pharmaceuticals provided the escitalopram and identical placebo for the study.

The investigators would like to thank the NIDDK staff (Dr. Patricia Roebuck, Rebecca Torrance, Rebekkah Van Raaphorst, Dr. Frank Hamilton, and Dr. Jose Serrano); the DSMB members (Drs. Henry Parkman, Brooks Cash, William Chey, Rona Levy, James Tonascia); the study coordinators (Verna J. Skinner, Mayo Clinic Jacksonville; Jason Bratten, Northwestern University; Jessica Chevalier, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center; Susanna Murphy, Mayo Clinic Scottsdale; Debra King, St. Louis University; Alexiz Brown, Baylor College of Medicine; and Melanie Wolfe, McMaster University Medical Center); and Lori R. Anderson for her administrative assistance.

Abbreviations

- FD

functional dyspepsia

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- TCAs

tricyclic antidepressants

- SSRIs

serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale

- GSRS

GI Symptom Rating Scale

- BMI

body mass index

- PLA

placebo

- AMI

amitriptyline

- ESC

escitalopram

- NDI

Nepean Dyspepsia Index

- NDT

nutrient drink test

- MTV

maximum tolerated volume

- ITT

intent to treat

- ANCOVA

analysis of covariance

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

Nicholas J. Talley: Research support: National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia; NIH; Abbott, Forest, Ironwood, Janssen, Pfizer, Prometheus, Rome Foundation.

G. Richard Locke, III: Research support: Ironwood.

Yuri A. Saito: Research support: Pfizer, Ironwood. Scientific Advisory Board: Salix.

Ann E. Almazar: No relevant disclosures.

>Ernest P. Bouras: No relevant disclosures.

Colin W. Howdin: Consultant for Takeda, Otsuka, Forest, Ironwood and Salix. Speaking honoraria from Otsuka, Takeda, Forest, Ironwood and GlaxoSmithKline International.

Brian E. Lacy: Scientific Advisory Board for Takeda, Ironwood, and Prometheus.

John K. DiBaise: No relevant disclosures.

Charlene M. Prather: No relevant disclosures.

Bincy P. Abraham: Research support: UCB. Consultant: Prometheus. Scientific Advisory Board for Janssen, Abbvie, UCB, Shire. Speaker: Janssen, Abbvie, UCB, Prometheus, Santaurus.

Hashem B. El-Serag: No relevant disclosures.

Paul Moayyedi: Speakers honoraria: Shire, Forest and AstraZeneca. Chair partly funded by an unrestricted donation to McMaster University from AstraZeneca.

Linda M. Herrick: Research support: Ironwood.

Lawrence A. Szarka: No relevant disclosures.

Michael Camilleri: No relevant disclosures.

Frank A. Hamilton: No relevant disclosures

Cathy Schleck: No disclosures to report.

Katherine Tilkes: No disclosures to report.

Alan R. Zinsmeister: No disclosures to report.

Writing Assistance: None

Author contributions:

Nicholas J. Talley: Study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing and editing, PI U01

G. Richard Locke: Study design, data collection, data analysis.

Yuri A. Saito: Data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing and editing

Ann E. Almazar: Data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing

Ernest P. Bouras: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Colin W. Howden: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Brian E. Lacy: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

John K. DiBaise: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Charlene M. Prather: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Bincy P. Abraham: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Hashem B. El-Serag: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Paul Moayyedi: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Linda M. Herrick: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Lawrence A. Szarka: Data collection, data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Michael Camilleri: Data interpretation, manuscript review and editing

Frank A. Hamilton: Data interpretation and manuscript review

Cathy D. Schleck: Data analysis, manuscript review and editing

Katherine E. Tilkes: Data collection and management.

Alan R. Zinsmeister: Data analysis, manuscript review and editing

REFERENCES

Authors names in bold designate shared co-first authors.

- 1.Tack J, Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia--symptoms, definitions and validity of the Rome III criteria. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:134–141. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kindt S, Tack J. Impaired gastric accommodation and its role in dyspepsia. Gut. 2006;55:1685–1691. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.085365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talley NJ, Walker MM, Aro P, et al. Non-ulcer dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia: an adult endoscopic population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1175–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:543–552. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, et al. Symptoms associated with hypersensitivity to gastric distention in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:526–535. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brook RA, Kleinman NL, Choung RS, et al. Functional dyspepsia impacts absenteeism and direct and indirect costs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacy BE, Weiser KT, Kennedy AT, et al. Functional dyspepsia: the economic impact to patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:170–177. doi: 10.1111/apt.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacy BE, Talley NJ, Locke GR, 3rd, et al. Review article: current treatment options and management of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58:367–378. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mertz H, Fass R, Kodner A, et al. Effect of amitriptyline on symptoms, sleep, and visceral perception in patients with functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:160–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otaka M, Jin M, Odashima M, et al. New strategy of therapy for functional dyspepsia using famotidine, mosapride and amitriptyline. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(Suppl 2):42–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Kerkhoven LA, Laheij RJ, Aparicio N, et al. Effect of the antidepressant venlafaxine in functional dyspepsia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:746–752. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.051. quiz 718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan VP, Cheung TK, Wong WM, et al. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with sertraline: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6127–6133. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch ME. Antidepressants as analgesics: a review of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26:30–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clouse RE. Antidepressants for functional gastrointestinal syndromes. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:2352–2363. doi: 10.1007/BF02087651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clouse RE, Lustman PJ, Geisman RA, et al. Antidepressant therapy in 138 patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a five-year clinical experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:409–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorard DA, Libby GW, Farthing MJ. Influence of antidepressants on whole gut and orocaecal transit times in health and irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:159–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tack J, Broekaert D, Coulie B, et al. Influence of the selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor, paroxetine, on gastric sensorimotor function in humans. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:603–608. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talley NJ, Locke GR, 3rd, Herrick LM, et al. Functional Dyspepsia Treatment Trial (FDTT): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of antidepressants in functional dyspepsia, evaluating symptoms, psychopathology, pathophysiology and pharmacogenetics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:523–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II37–II42. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junghard O, Lauritsen K, Talley NJ, et al. Validation of seven graded diary cards for severity of dyspeptic symptoms in patients with non ulcer dyspepsia. Eur J Surg Suppl. 1998:106–111. doi: 10.1080/11024159850191355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bijkerk CJ, de Wit NJ, Muris JW, et al. Outcome measures in irritable bowel syndrome: comparison of psychometric and methodological characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:122–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangel AW, Hahn BA, Heath AT, et al. Adequate relief as an endpoint in clinical trials in irritable bowel syndrome. J Int Med Res. 1998;26:76–81. doi: 10.1177/030006059802600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tack J, Delia T, Ligozio G, et al. A phase II placebo controlled randomized trial with tegaserod in functional dyspepsia patients with normal gastric emptying. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:A-20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talley NJ, Van Zanten SV, Saez LR, et al. A dose-ranging, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of alosetron in patients with functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:525–537. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talley NJ, Haque M, Wyeth JW, et al. Development of a new dyspepsia impact scale: the Nepean Dyspepsia Index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:225–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones M, Talley NJ. Minimum clinically important difference for the Nepean Dyspepsia Index, a validated quality of life scale for functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1483–1488. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, Greydanus MP, et al. Towards a less costly but accurate test of gastric emptying and small bowel transit. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:609–615. doi: 10.1007/BF01297027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cremonini F, Mullan BP, Camilleri M, et al. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic transit measurements for studies of experimental therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1781–1790. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camilleri M, Iturrino J, Bharucha AE, et al. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic measurement of gastric emptying of solids in healthy participants. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:1076–e562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chial HJ, Camilleri C, Delgado-Aros S, et al. A nutrient drink test to assess maximum tolerated volume and postprandial symptoms: effects of gender, body mass index and age in health. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:249–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boeckxstaens GE, Hirsch DP, van den Elzen BD, et al. Impaired drinking capacity in patients with functional dyspepsia: relationship with proximal stomach function. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1054–1063. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31:103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Therneau TM. How many stratification factors are “too many” to use in a randomization plan? Control Clin Trials. 1993;14:98–108. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bryson HM, Wilde MI. Amitriptyline. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in chronic pain states. Drugs Aging. 1996;8:459–476. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199608060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parkman HP, Van Natta ML, Abell TL, et al. Effect of nortriptyline on symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis: the NORIG randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2640–2649. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Oudenhove L, Tack J. Is the antidepressant venlafaxine effective for the treatment of functional dyspepsia? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:74–75. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talley NJ, Vakil N. Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2324–2337. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delaney BC, Moayyedi P, Forman D. Initial management strategies for dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD001961. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camilleri M. Editorial: is adequate relief fatally flawed or adequate as an end point in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:920–922. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.