Abstract

This paper aims to assess the role of individual types and cumulative life adversity for understanding depressive symptomatology and aggressive behavior. Data were collected in 2011 as part of the Teen Life Online and in Schools Study from 916 ethnically-diverse students from 12 middle, K-8, 6-12 and high schools in the Midwest United States. Youth reported an average of 4.1 non-victimization adversities and chronic stressors in their lifetimes. There was a linear relationship between number of adversities and depression and aggression scores. Youth reporting the highest number of adversities (7 or more) had significantly higher depression and aggression scores than youth reporting any other number of adversities suggesting exposure at this level is a critical tipping point for mental health concerns. Findings underscore an urgent need to support youth as they attempt to negotiate, manage, and cope with adversity in their social worlds.

Keywords: Life adversity, Depression, Aggressive behavior, Adolescents

There are many stressful experiences in childhood related to poor mental health and behavior. Many studies focus on non-victimization adversities and chronic stressors such as physical health problems, and others focus on problems specifically within the family context, such as alcohol and drug abuse and job loss. Indeed, research has documented that, individually, adverse life events such as inter-parental conflict (Buehler et al., 1997) and parental substance use (Elkins, McGue, Malone, & Iacono, 2004) are related to externalizing or aggressive behaviors. Cumulatively, life adversity is especially important for long term health risks such as depression and anxiety disorders (Goodyer & Altham, 1991; Hazel, Hammen, Brennan, & Najman, 2008; Kim, Conger, Elder Jr, & Lorenz, 2003; Phillips, Hammen, Brennan, Najman, & Bor, 2005; Rudolph & Flynn, 2007; Spinhoven et al., 2010; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormond, 2006; Turner & Lloyd, 2004), other psychiatric disorders (Benjet, Borges, & Medina-Mora, 2010; Benjet, Borges, Méndez, Fleiz, & Medina-Mora, 2011; Turner & Lloyd, 1995), substance use (Benjet, Borges, Medina-Mora, & Mendez, in press; Lloyd & Turner, 2008; Turner & Lloyd, 2003), and externalizing or aggressive behavior (Kim et al., 2003; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006). Further, retrospectively reported childhood adversities are related to first onset of DSM-IV disorders (mood, anxiety, substance abuse, disruptive behaviors) in adulthood with cumulative adversities playing a more critical role than any individual type (Green et al., 2010).

Although there appears to be a dose-response association between adversity and negative outcomes (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006) whether there is a “tipping point” for when amount of adversity is most strongly related to depressive symptomatology and aggressive behavior is unclear; and even less is known about whether there are specific groups of adversities that are most influential in adolescence while taking into account others, as research to date has focused on either specific and individual forms of adversity or cumulative adversity.

The current study aims to fill some of these gaps in the literature and provide some recommendations for prevention. Specifically we explore youth experiences with specific types of non-victimization life adversities and chronic stressors. Then we examine cumulative adversity more closely to see if there is a “tipping point” in which adversity is most closely related to depressive symptomatology and aggressive behavior.

Method

Participants

Data were collected in 2011 as part of a larger study focused on the risk and protective factors associated with the online experiences of an ethnically and racially diverse sample of sixth through 12th graders (N = 1,031). Participants were recruited from a total of 12 public schools (i.e., middle schools, K-8, 6-12, and high schools). Two schools were K-8, three were 6-8 middle schools, one was 6-12, and six were high schools (9th-12th grade). Six schools were located in a major metropolitan area, and six were in small non-metropolitan communities. Parental consent forms were returned by 49.8% of students.

Since the construct of life adversity is the main focus of the current paper we limit our analytic sample to the 916 youth who have complete data on these items. This sub-sample is comprised of 53% females (n = 486) and 47% males (n = 427) (three youth did not specify gender) with an average age of 14. Twelve percent of students were in the sixth grade (n = 107), 33% were in grades seventh – eighth (n = 303), and 55% in grades ninth – 12th (n = 501) (five youth did not have data on grade). Twenty-eight percent of youth self-identified as White, non-Hispanic (n = 258), 33% were Black, non-Hispanic (n = 306), 20% as Hispanic (n = 185), and 17% were of some other race (n = 154) (13 youth did not specify race or ethnicity). The majority of adolescents reported their country of birth was the U.S. (i.e., 88%). Most students (80%) reported that at least one parent had a high school education or higher (an additional 15% did not know either parent's educational attainment).

Procedure

Research assistants distributed informational flyers and consent forms (in English and Spanish) to students after a brief 10-minute presentation at schools. Students were told that the study focused on learning more about students' experiences with the Internet. At an agreed upon date with school administrators, the research team returned to schools to administer surveys via a web link to students who obtained parental consent. Surveys were programmed and administered using surveymonkey.com, and survey administration took place in school computer labs (or onsite labs created by the research team by bringing laptops into a classroom). Participants provided online assent at the beginning of the survey, and answered questions addressing topics such as general internet use, discrimination and victimization experiences, cultural orientation, and psychosocial functioning. On average, students completed surveys in 45 minutes. Research assistants were present to inform students of confidentiality, answer questions, and troubleshoot any technical difficulties. Each participant received a $15 gift certificate, and schools received a stipend. All procedures were approved by the University of Southern California and University of Illinois Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

Non-victimization life adversity and chronic stressors

Non-victimization life adversity and chronic stressors in childhood was assessed by a comprehensive lifetime adversity measure developed and validated on a sample of university students (Turner & Butler, 2003). This scale has also been utilized in multiple nationally studies conducted with youth across the United States. For example, Turner and colleagues noted an average of 3.38 non-victimization adversities among a nationally representative sample of 10-17 year old youth who participated in the Developmental Victimization Survey (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006). No differences were noted by sex; Hispanic youth (M = 3.86) and Black youth (M = 3.66) reported more adversity than White youth (M = 3.22) or youth of another race (M = 2.94). Adversity was also higher among youth living with a parent who a) had a high school education or lower, b) lived in a lower income household (< $20,000 annually), and c) lived in a stepfamily or with a single parent. The measure includes 15 non-violent traumatic events and chronic stressors. Nonviolent traumatic events include serious illnesses, accidents, and parental imprisonment; and chronic stressors include substance abuse by family members and homelessness. With respect to divergent validity, non-victimization adversity has been shown to have unique effects on mental health, distinct from effects of victimization experiences (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006). If a specific stressor was present at least once in the child's lifetime, they were given a code of 1 on that item.

For the current analyses adversity was examined in several different forms: individually, cumulatively, and through classification into distinct groups based on number. First, a measure of the total number of adversities was created, referred to as cumulative adversity, based on the total number of different types of adversity reported by youth for a possible 15 types. Next we categorized adversity into groups to examine the youth reporting the highest amounts of adversity more distinctly: a) none, b) limited adversity (1-4 types), c) multi adversity (5 or more types). Youth reporting five or more types (those above the mean) were classified as having multiple forms of adversity.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-12 was used to measure adolescents' depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). Sample items include “I felt I was just as good as other people” and “I had crying spells”. Responses range from 0=rarely or none of the time to 3=most or all of the time. For this study item level means were calculated rather than a sum. Participants' CES-D mean score was created if a minimum of 75% of the items were completed. Average depression score for the current sample was .85 (SD=.48). A Cronbach's α of .71 was found for the current study.

Aggressive behavior was measured through the use of the aggression subscale of the Youth Self Report of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991). This is a widely used measure of competencies, emotional and behavior problems in youth between the ages of 11-18. Average aggression score for the current sample was .34 (SD=.30). For this study item level means were calculated rather than a sum. Participants' aggression mean score was created if a minimum of 75% of the items were completed. A Cronbach's α of.84 was found in the current study.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 19.0 was used for all analyses (IBM SPSS 19.0, 2011). First, we reported the frequency of endorsement of each type of life adversity. Next, for each type of adversity we report the average number of total adversities experienced. Then using the count of total number of adversities we examine the respective beta coefficients (with zero as the reference category) to determine whether there is a “tipping point” for the largest relationship with depressive symptomatology and aggressive behavior while adjusting for gender, grade in school and race/ethnicity. For these analyses we conducted two multiple regressions (one for depressive symptoms and one for aggressive behavior) where each individual count of adversity was compared to all others (i.e., dummy coded). For example, youth reporting five adversities were coded as one and all other counts were coded as zero. This was done for each individual number for a total of seven adversity variables (seven or more were grouped together). Data analysis occurred in 2014.

Then using our classification of none, limited and multi adversity youth we explore which individual types of adversities are likely to fall into the multi adversity group, as well as whether different sub-groups of youth are more or less likely to be a part of each group (e.g., by gender, race/ethnicity). Finally, a series of multiple regressions were performed to examine the relationships of each individual type of adversity with a) depressive symptomatology and b) aggressive behavior, both with and without adjusting for cumulative adversity (30 models: 15 adversities × 2 (depression and aggression). We conducted analyses in a nested fashion. For each regression, Model 1 is the full model with the specific type of adversity under examination plus cumulative adversity (less the specific adversity time being examined). Model 2 is a nested model with only the specific type of adversity (plus demographic characteristics). The difference in R-square represents the change between the full and nested models to determine whether the inclusion of cumulative adversity makes a significant contribution to the model.

Results

Types of Life Adversity and Relationships with Experiencing Multiple Adversities

The most common types of non-victimization adversities faced by youth include having someone close to them die (57%), having someone close to them have a bad illness (55%), and having someone close to them have a bad accident (54%) (see Table 1). Less common adversities include living on the street (8%), having to repeat a school year (9%), and being sent or taken away from home (9%).

Table 1. Types of Non-victimization Life Adversity and Chronic Stressors Reported by Youth.

| Adversity type | % any (n = 916) | Limited adversity (1-4 types) (n = 430) | Multi adversity | Mean number of different adversities | n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| % low multi adversity (5- 6 types) (n = 203) | % high multi adversity (7+ types) (n = 172) | % any multi adversity (5 or more) (n = 375) | |||||

| Someone close died | 57 | 39 | 30 | 31 | 61 | 5.5 | 520 |

| Someone close had bad illness | 55 | 40 | 29 | 31 | 60 | 5.6 | 500 |

| Someone close had bad accident | 54 | 39 | 31 | 31 | 61 | 5.6 | 494 |

| Ever had bad illness | 36 | 33 | 31 | 35 | 67 | 6.0 | 328 |

| Parent arguing a lot | 34 | 26 | 29 | 45 | 74 | 6.4 | 312 |

| Parent lost job | 31 | 32 | 28 | 40 | 68 | 6.1 | 282 |

| Ever in bad accident | 27 | 35 | 27 | 38 | 65 | 6.1 | 250 |

| Parent drug or alcohol abuse | 26 | 20 | 32 | 48 | 80 | 6.9 | 240 |

| Someone close suicide attempt | 23 | 21 | 33 | 47 | 79 | 6.7 | 208 |

| Parent went to prison | 18 | 15 | 31 | 54 | 85 | 7.3 | 166 |

| Ever in bad natural disaster | 16 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 6.9 | 145 |

| Parent in war | 11 | 14 | 33 | 53 | 86 | 7.3 | 100 |

| Repeat school year | 9 | 21 | 21 | 58 | 79 | 7.4 | 81 |

| Sent or taken away | 9 | 11 | 24 | 64 | 89 | 8.3 | 78 |

| Live on street | 8 | 21 | 29 | 50 | 79 | 7.7 | 70 |

|

| |||||||

| Total no. adversities (Mean, SD) | 4.1 (2.9) | ||||||

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001. Note. Row percentages provided.

It was common for youth to experience multiple types of adversity in their lifetime: on average youth reported 4.1 adversities (standard deviation (SD) = 2.9), with a range of zero to 15. Twelve percent of youth (n = 111) reported no adversities, 47% (n = 430) between one – four types (limited), and 41% (n = 375) five or more types (multi). Given the diversity in terms of severity and frequency we highlight the multi-adversity group and further sub-divide that into low multi (five – six types, just above the mean), and high multi (seven or more types, 1 SD above the mean). The low multi adversity group comprises 22% (n = 203) of all youth and the high multi adversity 19% (n = 172) of all youth.

Youth with specific types of adversities were particularly likely to have a higher total number of adversities and fall into the multi adversity category. Specifically the following types of adversities all had about 80% of their members in the multi adversity group and had experienced, on average, seven or more types of adversities in their lifetime: parent went to prison, parent in war, repeat school year, sent or taken away, lived on street.

Youth with certain characteristics were more likely to report multiple adversities: number of adversities increased with grade in school with the youth in grades nine – 12 the most likely to have experienced multiple adversities (see Table 2). White, non-Hispanic and Black, non-Hispanic youth were more likely than Hispanic youth of any race to report multiple adversities, however youth of some other race, such as Asian, were the most likely to report multiple adversities.

Table 2. Adversity Classification by Demographic Sub-group of Youth.

| Adversity type | no adversity | limited adversity (1-4 types) (n = 430) | Multi adversity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| % low multi adversity (5- 6 types) (n = 203) | % high multi adversity (7+ types) (n = 172) | % any multi adversity (5 or more) (n = 375) | |||

| Child gender | |||||

| Male | 14 | 48 | 22 | 16 | 38 |

| Female | 11 | 46 | 22 | 21 | 43 |

| Child grade in school*** | |||||

| 6th | 13 | 61 | 14 | 12 | 26 |

| 7th – 8th | 15 | 48 | 19 | 17 | 37 |

| 9th – 12th | 10 | 43 | 25 | 21 | 47 |

| Race and ethnicity** | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 9 | 53 | 23 | 16 | 39 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 12 | 46 | 20 | 21 | 41 |

| Hispanic, any race | 19 | 44 | 19 | 17 | 36 |

| Other race | 10 | 41 | 28 | 21 | 49 |

| Mental health score (Mean, SD) | |||||

| Depression*** | .73 (.42) | .78 (.43) | .86 (.48) | 1.1 (.53)a | .97 (.52) |

| Aggression*** | .21 (.28) | .29 (.25) | .40 (.29)c | .49 (.34)b | .44 (.32) |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

High multi significantly higher than all other categories at p < .001 level.

High multi significantly higher than limited and none at p < .001 level and from low multi at the p < .05 level.

Low multi significantly higher than limited and none at p < .001 level.

Note. Row percentages provided.

Multiple Adversities and Depression and Aggression

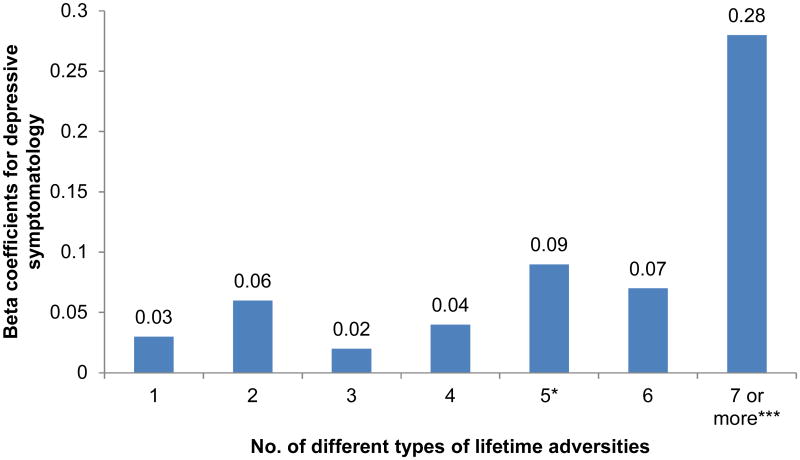

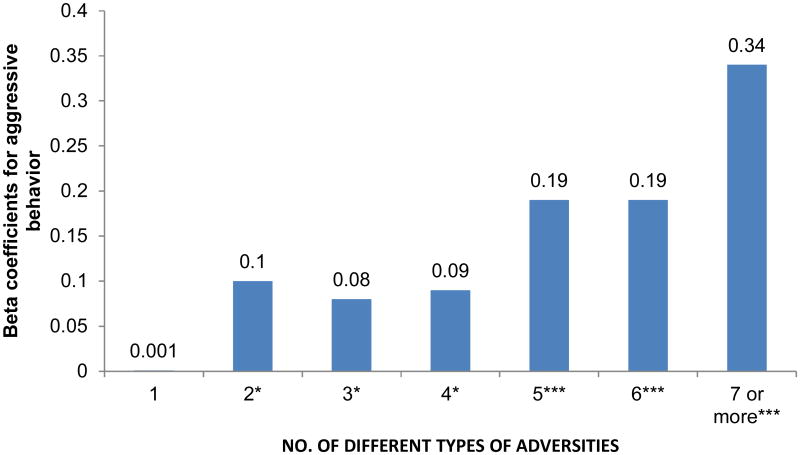

There was a linear relationship between number of adversities and depression and aggression (see Table 2, Figures 1 & 2). Youth reporting the highest multiple adversities (seven or more) had significantly higher depression and aggression scores than youth reporting any other level of adversity (see Table 2). Indeed, this high multi adversity group represented a noticeable jump in the size of the beta coefficient from those reporting all other counts of adversity, both for depression (see Figure 1, β = 0.28, =.06) and aggression (see Figure 2, β = 0.34, SE=.03) suggesting adversity at this level is a critical tipping point for behavioral and mental health concerns.

Figure 1.

Beta coefficients indicating relationship between the specific number of different types of non-victimization adversities reported and depressive symptomatology. Note. Reference group for each number is all other amounts (n = 894). *p < .05. ***p < .001.

Figure 2.

Beta coefficients indicating relationship between the specific number of different types of non-victimization adversities reported and aggressive behavior. Note. Reference group for each number is all other amounts (n = 895). *p < .05. ***p < .001.

Although cumulative adversity is the most powerful indicator of depression and aggression, with beta coefficients of .23 (p ≤ .001) and .30 (p ≤ .001), respectively after adjusting for grade, gender, and race/ethnicity, there were individual types of adversity that were related to depression and aggression, even after adjusting for total number of adversities (see Table 3). Specifically, the following adversities were uniquely related to depression and aggression: parents arguing a lot, having a parent with drug or alcohol abuse, having someone close attempt suicide, and having a parent go to prison. All of these individual types of adversity had significant but attenuated relationships with both depression and aggression even after adjusting for total number of adversities (See Model 1 columns). For most other types of adversity there was a relationship with depression and aggression which was eliminated after adjusting for total adversity with three exceptions – repeating a school year, being sent or taken away, and having to live on the street were positively associated with depressive symptomatology even after adjusting for cumulative adversity. Overall, regardless of specific type of adversity across both depression and aggression, the inclusion of cumulative adversity makes a significant contribution to the models.

Table 3. Nested Regression Models Using Depression and Aggression as Dependent Variables.

| Adversity type | Depressive symptomatology (n = 894) | Aggressive behavior (n = 895) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Model 1 Beta | Model 2 Beta | Model 1 Beta | Model 2 Beta | |

| Cumulative adversity (CA) | .23*** | .30*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Someone close died | -.01 | .09** | -.01 | .11*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .24*** | --- | .31*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .04 | .13 | .05 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.05*** | -.08*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Someone close had bad illness | -.08* | .04 | -.04 | .10** |

| Cumulative adversity | .28*** | --- | .33*** | --- |

| R-Square | .10 | .04 | .14 | .05 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.06*** | -.09*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Someone close had bad accident | -.05 | .06 | -.01 | .11*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .26*** | --- | .31*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .04 | .13 | .05 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.06*** | -.08*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Ever had bad illness | -.05 | .03 | .03 | .13*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .26*** | --- | .29*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .03 | .13 | .06 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.06*** | -.07*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Parent arguing a lot | .18*** | .24*** | .13*** | .23*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .13*** | --- | .23*** | --- |

| R-Square | .11 | .09 | .13 | .09 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.01*** | -.04*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Parent lost job | .06 | .12*** | -.01 | .09** |

| Cumulative adversity | .21*** | --- | .31*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .05 | .14 | .05 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.04*** | -.09*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Ever in bad accident | .003 | .07* | .05 | .13*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .23*** | --- | .29*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .04 | .13 | .06 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.05*** | -.07*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Parent drug or alcohol abuse | .14*** | .21*** | .17*** | .26*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .16*** | --- | .21*** | --- |

| R-Square | .10 | .08 | .14 | .11 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.02*** | -.03*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Someone close suicide attempt | .11*** | .18*** | .09** | .19*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .18*** | --- | .26*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .07 | .13 | .07 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.03*** | -.06*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Parent went to prison | .09** | .17*** | .15*** | .24*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .19*** | --- | .23*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .06 | .14 | .10 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.03*** | -.04*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Ever in bad natural disaster | .01 | .08* | -.002 | .09** |

| Cumulative adversity | .23*** | --- | .30*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .04 | .13 | .05 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.05*** | -.08*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Parent in war | -.05 | .02 | .05 | .13*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .26*** | --- | .28*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .03 | .13 | .06 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.06*** | -.07*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Repeat school year | .07* | .13*** | .02 | .09** |

| Cumulative adversity | .21*** | --- | .29*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .05 | .13 | .05 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.04*** | -.08*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Sent or taken away | .07* | .15*** | .05 | .15*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .20*** | --- | .28*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .06 | .13 | .06 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.03*** | -.07*** | ||

|

| ||||

| Live on street | .07* | .13*** | .04 | .12*** |

| Cumulative adversity | .21*** | --- | .29*** | --- |

| R-Square | .09 | .05 | .13 | .06 |

| Difference in R-Square | -.04*** | -.07*** | ||

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Note. All regression models adjust for gender, grade, race and ethnicity. Model 1 is the full model with each type of adversity plus cumulative adversity (less the specific adversity time being examined). Model 2 is a nested model with only the specific type of adversity (plus demographic characteristics). Difference in R-square represents the change between the full and nested models to determine whether the inclusion of cumulative adversity makes a significant contribution to the model.

Discussion

The findings of the current research underscore the importance of assessing for a wide array of types of adversities when considering the mental health and behavior of teens. On average, adolescents in the Teen Life Online and in Schools Study reported 4.1 non-victimization adversities and chronic stressors. This is a rate higher than reported among youth (ages 10-17) nationally (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006). Although we found the most common adversities were having someone close die or have a bad accident or illness, results indicate parents exert a powerful influence on adolescent mental health and behavior; types of adversity having the strongest associations with depressive symptoms and aggressive behavior were parent drug and alcohol use, and parents who regularly argue. This is consistent with existing literature that has shown that familial factors are important predictors of depressive symptoms and problem behavior (Buehler et al., 1997; Elkins et al., 2004; Gest, Reed, & Masten, 1999; Ohannessian, 2013; Torvik, Rognmo, & Tambs, 2011); and are the most relevant for predicting first onset of psychiatric disorder in adulthood (Green et al., 2010). Research suggests that prevention and intervention targeted at young children and their families can decrease the likelihood of deviant outcomes, including substance use, violence and delinquency during adolescence (Webster-Stratton & Taylor, 2001; Yoshikawa, 1994). Continued attention towards these vulnerable youth is warranted.

Multiple Adversities

Almost half of the youth in this study (41%) had experienced multiple (five or more) adversities in their lifetime; one in five had experienced seven or more. As has been noted in previous research (Kim et al., 2003; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006), more adversity was related to a higher likelihood of recent depressive symptoms as well as aggressive behavior. Our findings contribute to this literature by revealing that there is a tipping point for non-victimization adversity, with seven or more adversities associated with a noticeable jump in the likelihood of depressive symptomatology and aggressive behavior regardless of type. This may be a useful, quick tool for practitioners who are trying to identify teens who may be at higher risk for mental health and behavioral difficulties. Professionals need to make sure youth have access to sources of support; particularly for situations when problems occur within the family. If such youth prove difficult to reach, given their families may not be amenable to some of the more traditional prevention avenues such as family-centered intervention; schools and other adults, such as coaches, extended family, peers and even online support systems may prove the most efficient means of reaching this population. Researchers and practitioners need to systematically search for and assess for potential cumulative effects of adverse life events.

Particular attention needs to be drawn to youth experiencing some of the less common but nonetheless, influential types of adversity. Specifically, almost all the youth who ever had a parent in prison, had a parent go to war, lived on the street, were sent or taken away from their families, or had to repeat a school year had experienced multiple adversities, on average, seven or more adversities. Not all adversities are equal in terms of their potential impact on depression and aggression. Screening for these specific experiences could be a useful way to easily identify this more vulnerable group of youth. Not only are these youth experiencing a multitude of adversities, they are more likely to report depressive symptoms and aggressive behavior based on their multi adversity classification. Further, past research also suggests a linear relationship between number of life adversities and poly-victimization – youth who experienced multiple types (usually four or more) of victimization in any given year (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007, 2009; Finkelhor, Turner, Hamby, & Ormrod, 2011; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006). Studies that focus on one or a limited number of adversities are likely to underestimate the burden these youth are under. Prevention and intervention can be most effective when practitioners assess their clients covering a broad spectrum of both victimization and non-victimization adversities. Findings could then be supplemented with problem-specific follow-up in the most critical areas.

Cumulative Adversity and Internalizing and Externalizing Problems

Our findings support the existing literature indicating that cumulatively, life adversity is especially important for long term health risks such as depression and anxiety disorders (Goodyer & Altham, 1991; Hazel et al., 2008; Phillips et al., 2005; Rudolph & Flynn, 2007; Spinhoven et al., 2010; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006; Turner & Lloyd, 2004). There is more limited knowledge regarding the impact of cumulative adverse life events on adolescent externalizing or aggressive behavior but what there is indicates a relationship (Kim et al., 2003). We add to this scant literature by documenting a similarly strong connection between adversity and aggressive behavior. A number of studies have explored biological explanations for such reactions to stress (Frodl, Reinhold, Koutsouleris, Reiser, & Meisenzahl, 2010; Lovallo, 2013; Rao et al., 2010; Walsh et al., 2014) which point to individual differences in processing incidents. For example, among healthy young adults, those who experienced high degrees of adversity prior to age 16 had diminished reactivity to social stress including reduced cortisol and heart rate reactivity, diminished cognitive capacity, and unstable regulation of affect, leading to behavioral impulsivity and antisocial tendencies (Lovallo, 2013). Exposure to childhood adversities affects the developing adolescent brain in ways that could be critical to short- and long-term well-being. Psychosocial protective factors may influence such pathways. Indeed, among maltreated children who showed a flattened diurnal cortisol curve, the introduction of family-based therapeutic intervention resulted in the curve becoming normal indicating the important influence of positive family behaviors in regulating hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function (Fisher, Stoolmiller, Gunnar, & Burraston, 2007). Given the strong influence of family-related adverse life events found in the current study, support for family-based prevention and intervention should be a priority.

Limitations

Although the current study has many strengths including its focus on multiple adversities and examining a possible tipping point, which has clear clinical implications, an important limitation to acknowledge is the cross-sectional nature of the data. It is unclear whether adjustment outcomes preceded or followed the adversity. Future research should use longitudinal and more experimentally-based designs to test the impact of experiencing multiple forms of adversity on mental health and behavioral outcomes for adolescents. In addition, future studies should explore factors that may protect youth from the negative impact of these adversities. Our measurement of adversity could also be strengthened. Specifically, future research which examines the frequency and duration of each experience as well as the impact will make an important contribution to the field.

Conclusions

Youth experience a number of types of adversity in their lives. The more adversity one experiences the more likely one is to have depressive symptoms and aggressive behavior. Youth experiencing seven or more adversities may be particularly vulnerable and thus an important group to target for prevention. The current study findings underscore an urgent need to support youth as they attempt to negotiate, manage, and cope with adversity throughout their lives. A comprehensive approach to assessment will better serve to identify the most seriously troubled youth.

Research Highlights.

Youth with 7+ life adversities may be a particularly vulnerable group.

Urgent need to support youth as they negotiate, manage, and cope with adversity.

A comprehensive approach will help identify the most seriously troubled youth.

Acknowledgments

Kimberly J. Mitchell, Crimes against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire This research was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD061584 (Brendesha Tynes, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kimberly J. Mitchell, University of New Hampshire

Brendesha Tynes, University of Southern California, Rossier School of Education.

Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Arizona State University

David Williams, Harvard School of Public Health.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME. Chronic childhood adversity and onset of psychopathology during three life stages: childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Journal of psychiatric research. 2010;44(11):732–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Mendez E. Chronic childhood adversity and stages of substance use involvement in adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.002. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Méndez E, Fleiz C, Medina-Mora ME. The association of chronic adversity with psychiatric disorder and disorder severity in adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;20(9):459–468. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Anthony C, Krishnakumar A, Stone G, Gerard J, Pemberton S. Interparental conflict and youth problem behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1997;6(2):233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, McGue M, Malone S, Iacono WG. The effect of parental alcohol and drug disorders on adolescent personality. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):670–676. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development And Psychopathology. 2007;19(1):149–166. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33(7):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Hamby SL, Ormrod R. Polyvictimization: Children's exposure to multiple types of violence, crime, and abuse. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs Office of Juvenile Justice and Deliquency Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M, Gunnar MR, Burraston BO. Effects of a therapeutic intervention for foster preschoolers on diurnal cortisol activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(8):892–905. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodl T, Reinhold E, Koutsouleris N, Reiser M, Meisenzahl EM. Interaction of childhood stress with hippocampus and prefrontal cortex volume reduction in major depression. Journal of psychiatric research. 2010;44(13):799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gest SD, Reed MGJ, Masten AS. Measuring developmental changes in exposure to adversity: A life chart and rating scale approach. Development And Psychopathology. 1999;11(01):171–192. doi: 10.1017/s095457949900200x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer IM, Altham P. Lifetime exit events and recent social and family adversities in anxious and depressed school-age children and adolescents—II. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1991;21(4):229–238. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90002-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives Of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazel N, Hammen C, Brennan P, Najman J. Early childhood adversity and adolescent depression: the mediating role of continued stress. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(4):581–590. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM SPSS 19.0. Statistical package for the social sciences. Armonk, NY: IBM; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Conger RD, Elder GH, Jr, Lorenz FO. Reciprocal influences between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2003;74(1):127–143. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd DA, Turner RJ. Cumulative lifetime adversities and alcohol dependence in adolescence and young adulthood. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93(3):217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR. Early life adversity reduces stress reactivity and enhances impulsive behavior: Implications for health behaviors. International journal of psychophysiology. 2013;90(1):8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian C. Parental problem drinking and adolescent psychological problems: The moderating effect of adolescent-parent communication. Youth & Society. 2013;45(1):3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips NK, Hammen CL, Brennan PA, Najman JM, Bor W. Early adversity and the prospective prediction of depressive and anxiety disorders in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33(1):13–24. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-0930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Chen LA, Bidesi AS, Shad MU, Thomas MA, Hammen CL. Hippocampal changes associated with early-life adversity and vulnerability to depression. Biological psychiatry. 2010;67(4):357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M. Childhood adversity and youth depression: Influence of gender and pubertal status. Development And Psychopathology. 2007;19(02):497–521. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P, Elzinga BM, Hovens JG, Roelofs K, Zitman FG, van Oppen P, Penninx BW. The specificity of childhood adversities and negative life events across the life span to anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(1-2):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.132. Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torvik FA, Rognmo K, Tambs K. Alcohol use and mental distress as predictors of non-response in a general population health survey: the HUNT study. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2011;47(5):805–816. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0387-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner H, Finkelhor D, Ormond R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Butler MJ. Direct and indirect effects of childhood adversity on depressive symptoms in young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2003;32(2):89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(1):13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Lifetime traumas and mental health: The significance of cummulative adversity. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(4):360–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Cumulative adversity and drug dependence in young adults: racial/ethnic contrasts. Addiction. 2003;98(3):305–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Stress burden and the lifetime incidence of psychiatric disorder in young adults: racial and ethnic contrasts. Archives Of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(5):481. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh ND, Dalgleish T, Lombardo MV, Dunn VJ, Van Harmelen AL, Ban M, Goodyer IM. General and specific effects of early-life psychosocial adversities on adolescent grey matter volume. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Taylor T. Nipping early risk factors in the bud: Preventing substance abuse, delinquency, and violence in adolescence through interventions targeted at young children (0–8 years) Prevention Science. 2001;2(3):165–192. doi: 10.1023/a:1011510923900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H. Prevention as cumulative protection: effects of early family support and education on chronic delinquency and its risks. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115(1):28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]