Abstract

Azide-containing amino acids are valuable building blocks in peptide chemistry, because azides are robust partners in several bioorthogonal reactions. Replacing polar amino acids with apolar, azide-containing amino acids in solid-phase peptide synthesis can be tricky, especially when multiple azide residues are to be introduced in the amino acid sequence. We present a strategy for effectively incorporating multiple azide-containing residues site-specifically.

INTRODUCTION

Azide-containing peptides have gained prominence in chemistry1 due to the success of the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction2–4 for site-specifically modifying peptides and proteins. The bioorthogonal strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) reaction5 and the Staudinger ligation6,7 also exploit the azide functional group to expand the range of non-natural functional groups that can be incorporated into amino acid sequences.8–10 Several amino acids with azide groups in the side chain have been reported for use in SPPS1 (e.g., Nα-Fmoc-protected derivatives of azidonorleucine,11,12 azidonorvaline,12 azidohomoalanine,12 and azidoalanine13), and these have been routinely used to site-specifically introduce into peptides a single bioorthogonal reaction site. Peptides in which several azides have been site-specifically incorporated have also been reported, and these serve as key intermediates in the syntheses of tools for chemical biology14,15,16–18,19–21 and of hybrid biomaterials.22–26,27 Each of these examples relies upon suitably protected azide-containing amino acids in solid-phase peptide synthesis. A complementary strategy to incorporate high degrees of azide functional groups site-specifically into amino acid sequences should contribute to the continued growth of applications that exploit these peptides. Herein we present a general strategy for replacing polar residues with apolar, azide-containing residues (Figure 1). We demonstrate below that the diazotransfer reagent imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide28 can achieve high degrees of conversion of amine to azide. In combination with an orthogonal protecting group strategy, we exploit the reactivity of this diazotransfer reagent to site-specifically introduce azide groups on-resin while leaving some lysine residues unaffected.

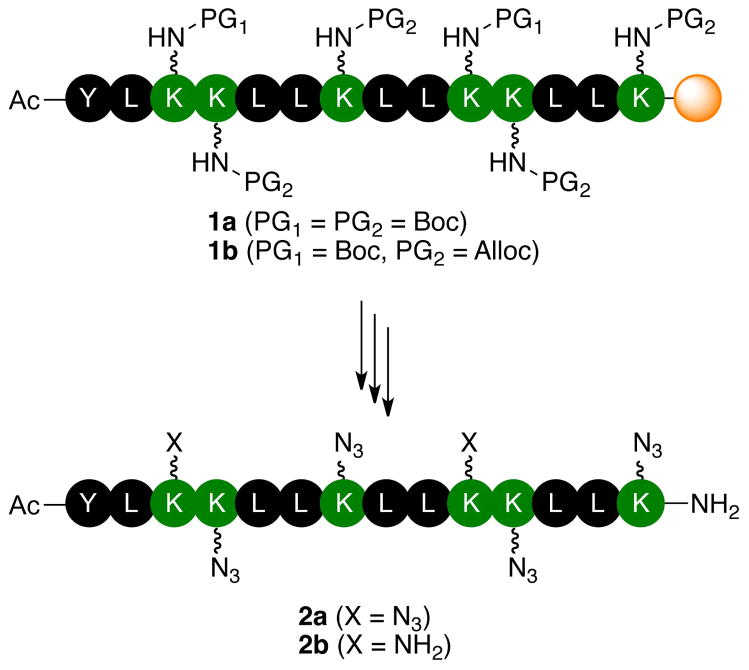

Figure 1.

Peptides containing multiple azide functional groups are prepared in a site-specific manner (Y = tyrosine, L = leucine, K = lysine; side chain protecting group on tyrosine is not shown).

Solid-phase peptide synthesis provides rapid access to a broad spectrum of chemical structures.29–31 While the technology is mature and robust, attention must still be paid to subtle factors that make the synthesis of some peptides especially challenging or even intractable. An abrupt decline in the efficiency of the Nα-protecting group elimination and/or amino acid coupling reactions during peptide chain assembly is the hallmark of these so-called “difficult sequences,” and results in low product yield.32–35 The causes of this poor reactivity include association of peptide chains while they are still attached to the solid support36,37 and/or changes to the swelling properties of the resin as the peptide chain is assembled.36,38 Guidelines for anticipating difficult sequences cite the number of or sequence of apolar residues as indicators of potential problems.32–35 Polar residues with small side chain protecting groups help solubilize the growing peptide chain in the reaction solvent so that the reactive chain end is accessible to reagents. Amino acid residues with apolar side chains or with polar side chains that have large, apolar protecting groups lower the solubility of the resin-bound peptide and strengthen hydrogen bonding. Nonetheless, difficult sequences are usually found by chance, and there is little reward for these discoveries. When we replaced Lys3 and Lys11 of peptide 1a (Figure 1) with propargylglycine, we encountered problems during synthesis that are associated with “difficult sequences.” We observed 1) a significant increase in deletion peptides (especially of peptides missing Leu5 or Leu 6) which could be overcome by increasing the number of equivalents of amino acid in the coupling reactions and introducing double couplings, and 2) inefficient elimination of Fmoc protecting groups which necessitated repeated (up to five times) treatment with the deprotection solution. Figure 1 presents a strategy that is versatile enough that we can replace any number of the polar residues with amino acids that participate in azide-alkyne click reactions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Solution-Phase Diazotransfer

Imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide hydrochloride salt (ISA•HCl)28 has been shown to be an efficient diazotransfer reagent in a variety of contexts relevant to our objective. We are aware that the reagent is impact sensitive,39 but we found it convenient to prepare and handle. In the presence of a Cu(II) salt and base, ISA•HCl has been used to convert amines into azides on various proteins,40 polymers,41 oligosaccharides,42 and dendrimers;43 this suggested to us that the diazotransfer reagent is capable of achieving high degrees of reaction on peptides with multiple exposed lysine side chains. The reagent has also been successfully applied to modify resin-bound amines.44–46 Löwik and co-workers demonstrated that nearly quantitative conversion of the N-terminus of resin-bound and side chain-protected peptides could be achieved in the presence of any natural amino acid except methionine and S-trityl cysteine.44 We, therefore, focused our attention on ISA•HCl as a diazotransfer reagent.

To evaluate the potential for ISA•HCl to effect diazotransfer reactions at several lysine residues in a peptide, we first investigated the solution-phase reaction between peptide 3 and ISA•HCl. Peptide 3 is a fourteen-residue peptide that contains six lysine residues arranged such that they are all on one face of an amphipathic α-helix.47 Resin-bound peptide 1a was manually synthesized by standard peptide synthesis protocols. The amino acid sequence was assembled on a polyethyleneglycol-based Rink amide resin with Nα-Fmoc-protected amino acid derivatives (i.e., Fmoc-Leu-OH, Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH, and Fmoc-Tyr(OtBu)-OH) activated with HBTU in the presence of HOBt and DIEA in DMF. Each coupling reaction was performed for 45 min. After each amino acid was coupled to the resin, the resin was treated with Ac2O to cap any unreacted peptide chains. The Fmoc group was eliminated by treating the resin with 20% piperidine in DMF for 5 min followed by a second treatment with 20% piperidine in DMF for 5 min. The extent of elimination of the Fmoc group was monitored by UV absorbance at 300 nm following a modified literature procedure.48 We observed no problems by this method during the assembly of the peptide on resin. Cleavage of the peptide from the resin and concomitant elimination of the side chain-protecting groups was accomplished in 2 h by treating the resin with TFA/iPr3SiH/H2O (Figure 2a). Peptide 3, purified by preparative reversed-phase HPLC, was obtained as a colorless powder after lyophilization. The purity of the collected peptide was determined by analytical HPLC, and the identity of the peptide was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

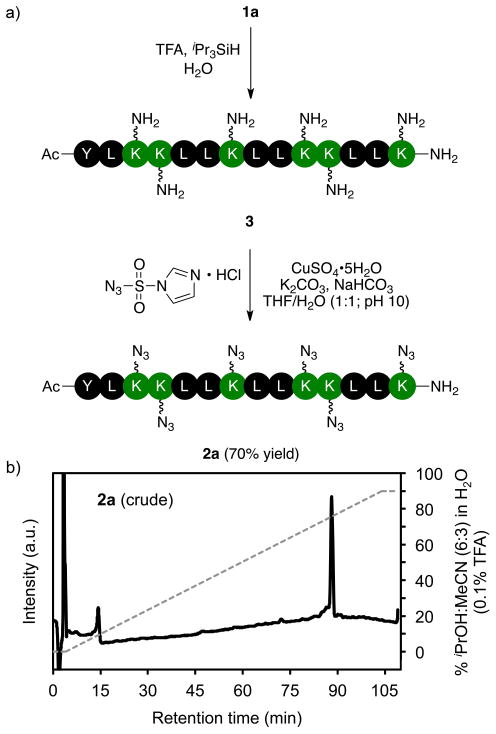

Figure 2.

a) Solution-phase reaction in which ISA•HCl effects the transformation of multiple lysine residues to azidonorleucine residues. b) Chromatogram of the crude reaction product 2a (solid line). The dashed line indicates the solvent composition during elution of the peptide at 1 mL/min from a C4 column (solvent A = H2O + 0.1% TFA; solvent B = iPrOH/MeCN/H2O (6:3:1 v/v/v) + 0.1% TFA).

All six lysine residues in peptide 3 were transformed to an azidonorleucine residue to yield peptide 2a (Figure 2). Diazotransfer reactions were performed in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of THF and H2O, because peptide 2a is not soluble in H2O. The reactions were monitored by reversed-phase HPLC, and were allowed to proceed until the desired product was the only observable peak. Aqueous solutions of 3 and CuSO4•5H2O (0.02 eq/NH2) were initially acidic, and so K2CO3 (3 eq/NH2) was added to neutralize the solutions. Additional base is needed to activate the diazotransfer reagent, ISA•HCl.28 The reaction mixture pH was adjusted to 10 with saturated NaHCO3 (aq). Under these conditions, we were able to obtain exclusively peptide 2a using ISA•HCl (4 eq/NH2) within 3 h. The analytical HPLC trace of the reaction mixture (Figure 2b) suggests that the reaction mixture is free of side products and intermediates. That the reaction is essentially quantitative supports conclusions drawn in prior reports of the reaction of ISA•HCl with polysaccharides41 and dendrimers.43 Peptide 2a was obtained in 70% yield after purification by flash column chromatography.

On-Resin Diazotransfer

Solution-phase diazotransfer reactions are convenient for converting primary amines to azides, but an alternative strategy is needed to site-specifically transform only a fraction of the available amines. We envisaged that a pair of orthogonal protecting groups for the lysine side chains would allow us to site-specifically introduce azidonorleucine residues into amino acid sequences that contained lysine residues that we wanted to remain unaltered. Allyloxycarbonyl (Alloc) protecting groups can be selectively removed in the presence of t-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) protecting groups49 and on-resin,50,51 and so we used this orthogonal pair of protecting groups as a test-bed to investigate whether ISA•HCl could effect the transformation of multiple lysine residues into azidonorleucine residues on-resin.

Resin-bound peptide 1b was assembled following the same protocol used to prepare peptide 1a, except that Fmoc-Lys(Alloc)-OH was used in place of Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH at four positions in the amino acid sequence. Importantly, no difficulties were encountered when we replaced Nε-Boc-protected lysine residues with Nε-Alloc-protected lysine residues; the assembly of 1b was as straightforward as the synthesis of peptide 1a. The crude purity of 1b was determined by characterization of peptide 4. Treatment of 1b with TFA/iPr3SiH/H2O resulted in cleavage of the peptide from the resin and elimination of the Boc and t-butyl ether protecting groups, but not the Alloc groups. The analytical HPLC trace of 4 in Figure 3b illustrates high crude purity of resin-bound peptide 1b, which is desirable for assessing the overall efficiency of the planned deprotection-diazotransfer-cleavage/deprotection sequence.

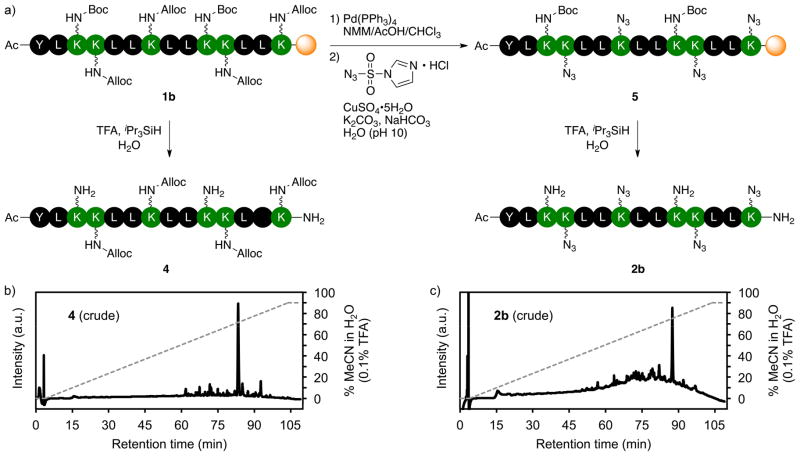

Figure 3.

a) Reaction sequence for site-specific diazotransfer to multiple lysine residues on a polyethyleneglycol-based resin. b) Chromatogram of the crude product 4 (solid line) illustrates the purity of the resin-bound peptide before the deprotection-diazotransfer-cleavage/deprotection sequence. c) Chromatogram of the crude reaction product 2b (solid line). The dashed line in panels (b) and (c) indicates the solvent composition during elution of the peptide at 1 mL/min from a C18 column (solvent A = H2O + 0.1% TFA; solvent B = MeCN/H2O (9:1 v/v) + 0.1% TFA).

Site-specific introduction of four azidonorleucine residues was accomplished through a three-step sequence (Figure 3). First, quantitative and selective elimination of the Alloc protecting groups from resin-bound peptide 1b was effected by treating the resin with Pd(PPh3)4 in NMM/AcOH/CHCl3.52 Second, the ISA-mediated diazotransfer reaction was performed in H2O under conditions that were otherwise identical to the solution-phase conditions described above. While the solution-phase transformation of 3 to 2a required a co-solvent to keep 2a in solution, the transformation of 1b to 5 required no organic co-solvent because the polyethyleneglycol-based support swells in H2O. Finally, the peptide was cleaved from the resin and the remaining protecting groups were removed by treating the resin-bound peptide with TFA/iPr3SiH/H2O. The crude purity of the product was assessed by analytical HPLC (Figure 3c). We were pleased to see that 1b was cleanly transformed into 2b. Had the on-resin deprotection-diazotransfer reaction sequence been incomplete, then products more polar than the target peptide would be observed at lower retention times. The azidonorleucine-containing peptide 2b was purified by reversed-phase HPLC.

CuAAC Reaction of an Azide-Rich Peptide

To demonstrate the suitability of azide-rich peptides for bioorthogonal transformations, we focused on the CuAAC reaction (Figure 4a).2–4 Alkyne 6 is a second-generation dendron53 with peripheral hydroxyl groups. The combination of the highly branched structure of 6 and the close proximity of conjugation sites in 2a should serve as a demanding test of how well the CuAAC reaction tolerates sterically encumbered substrates. Peptide 2a is insoluble in H2O, but could be solubilized in a mixed solvent of THF/H2O (1:1 v/v). The CuAAC reaction of 2a and 6 was, therefore, performed in THF/H2O (1:1 v/v) with CuSO4•5H2O as the catalyst source and sodium ascorbate as an in situ reducing agent. The reaction was deemed complete after 16 h when 7 was the only species observed in the ESI–MS of an aliquot from the reaction mixture. Peptide-dendron conjugate 7 was obtained in 57% yield after purification by reverse-phase HPLC. The analytical HPLC and MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of 7 (Figure 4b,c) demonstrate the purity of the isolated product. Furthermore, the observed isotope pattern and the simulated spectrum are in close agreement.

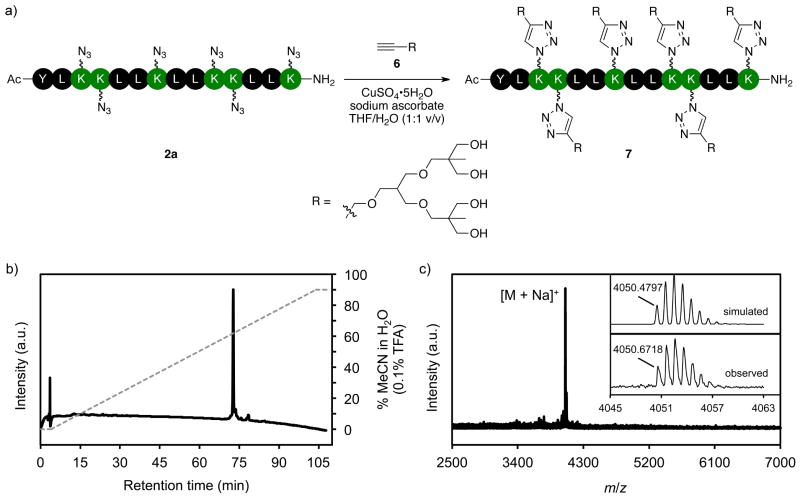

Figure 4.

a) Scheme showing the CuAAC reaction of azide-rich peptide 2a. b) Chromatogram of the product 7 (solid line). The dashed line indicates the solvent composition during elution of the peptide at 1 mL/min from a C18 column (solvent A = H2O + 0.1% TFA; solvent B = MeCN/H2O (9:1 v/v) + 0.1% TFA). c) MALDI-TOF Mass spectrum of 7. The inset compares the simulated54,55 isotope pattern (upper) with the observed isotope envelope for the [7 + Na]+ ion (C191H343N33O58Na).

CONCLUSION

Peptides are attractive building blocks in bioorganic and supramolecular chemistry56–59 because of the available diversity of amino acid sequences and their predictable conformational properties. Bioorthogonal reactions offer convenient methods to introduce non-native functionality into peptide sequences.8–10 The standard approach to preparing azide-containing peptides by solid-phase peptide synthesis relies upon suitably protected amino acids with azide functional groups in the side chain.1 We have described a complementary strategy wherein side-chain amine groups are converted to azide functional groups through the action of an imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide reagent after assembly of the peptide according to standardized protocols. The compatibility of this reagent with canonical amino acids44 suggests that the approach can be extended to a wide range of peptides. We expect that this strategy will be advantageous for peptides in which multiple azide groups are to be introduced and for amino acid sequences that are prone to aggregation during solid-phase synthesis.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Fmoc-Leu-OH, Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH, Fmoc-Lys(Alloc)-OH, Fmoc-Tyr(tBu)-OH, O-(benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), hydrochloric acid, N-methylmorpholine (NMM), sodium azide, dichloromethane, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), methanol (MeOH), diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), piperidine, acetyl chloride (AcCl), tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0), diethyl ether (Et2O), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate (EDTA), acetonitrile (MeCN), acetic anhydride (Ac2O), imidazole, triisopropylsilane (iPr3SiH), potassium carbonate (anhydrous), sulfuryl chloride, sodium diethyldithiocarbamate trihydrate, copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate, ethanol (EtOH), 5-nonanone, 1,1,1-tris(hydroxymethyl)ethane, anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF), boron trifluoride diethyl etherate, 3-chloro-2-(chloromethyl)prop-1-ene, dry sodium hydride, 15-crown-5, tetrahydrofuran (THF), ethyl acetate (EtOAc), sodium hydroxide, hexanes, sodium chloride, magnesium sulfate, hydrogen peroxide solution (30% w/w), 0.5 M solution of 9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (9-BBN) in THF, 80 wt% solution of propargyl bromide in toluene, Dowex® 50WX2 hydrogen form (50–100 mesh), molecular sieve (4Å), and isopropanol (iPrOH) were used as received. H-Rink Amide-ChemMatrix resin (0.51 mmol/g) was swelled in CH2Cl2 for 1 h prior to use.

Techniques

The MALDI-TOF data were recorded on a Bruker Autoflex II TOF/TOF workstation. MALDI-TOF samples (10 mg/mL) were prepared in MeCN/H2O with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as the matrix. Equal volumes of the matrix and peptide solutions were mixed and 1 μL of the mixture was injected onto the target plate. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using Whatman silica gel 60 Å plates (250 μm) with fluorescent indicator and visualized using a UV lamp (254 nm) or KMnO4 stain. Flash column chromatography was performed on a Teledyne Isco CombiFlash Rf with RedSep Rf Normal Phase disposable silica columns. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on a Waters 1525 Binary pump equipped with a Waters 2489 UV/Visible Detector set at 210 nm and 280 nm. To determine the analytical purity of samples, the HPLC was equipped with a SunFire™ C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm; Waters) or PROTO™ 300 C4 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, 300 Å; Higgins) operating at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and a solvent gradient of 1%/min. Purification of samples was done on the HPLC equipped with a SunFire™ C18 (5 μm, 19 mm × 250 mm) column operating at a flow rate of 17 mL/min and a solvent gradient of 5%/min. Absorbance of peptide solutions in deionized water at 280 nm was recorded on an Evolution 201 spectrophotometer using a 1-cm quartz cuvette. The concentration of the peptide was calculated from the absorbance using Beer’s Law and an extinction coefficient (ε) for tyrosine of 1490 L mol−1 cm−1.

General Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis Procedures. Single Coupling Protocol

To a solution of the Fmoc-protected amino acid (0.52 M), HBTU (0.51 M), and HOBt (0.52 M) in DMF, DIEA (2 eq/Fmoc-protected amino acid) was added. A sufficient volume of the solution to deliver 10 eq Fmoc-protected amino acid per reactive group on the resin was transferred to a peptide synthesis vessel containing the swelled resin. The reaction mixture was agitated for 45 min. Liquids were removed from the reaction vessel by vacuum filtration, and the resin was washed sequentially with DMF (10 mL/g) twice, CH2Cl2 (10 mL/g) twice, and DMF (10 mL/g) twice.

Double Coupling Protocol

To a solution of the Fmoc-protected amino acid (0.52 M), HBTU (0.51 M), and HOBt (0.52 M) in DMF, DIEA (2 eq/Fmoc-protected amino acid) was added. A sufficient volume of the solution to deliver 10 eq Fmoc-protected amino acid per reactive group on the resin was transferred to a peptide synthesis vessel containing the swelled resin. The reaction mixture was agitated for 45 min. Liquids were removed from the reaction vessel by vacuum filtration, and the resin was washed sequentially with DMF (10 mL/g) twice, CH2Cl2 (10 mL/g) twice, and DMF (10mL/g) twice. To a solution of the Fmoc-protected amino acid (0.52 M), HBTU (0.51 M), and HOBt (0.52 M) in DMF, DIEA (2 eq/Fmoc-protected amino acid) was added. A sufficient volume of the solution to deliver 10 eq Fmoc-protected amino acid per reactive group on the resin was transferred to a peptide synthesis vessel containing the swelled resin. The reaction mixture was agitated for 45 min. Liquids were removed from the reaction vessel by vacuum filtration, and the resin was washed sequentially with DMF (10 mL/g) twice, CH2Cl2 (10 mL/g) twice, and DMF (10 mL/g) twice.

Protocol for Capping and Acetylation of the N-Terminus

To the resin, a solution of DMF/DIEA/Ac2O (9:0.5:0.5 v/v/v; 5 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was gently agitated for 5 min. Liquids were removed from the reaction vessel by vacuum filtration, and the resin was washed sequentially with DMF (10 mL/g) twice, CH2Cl2 (10 mL/g) twice, and DMF (10 mL/g) twice.

Nα-Fmoc Deprotection Protocol

A stock solution of 20% (v/v) piperidine in DMF was prepared fresh each day. A portion of the stock solution (5 mL/g) was added to the resin, and the mixture was gently agitated for 5 min. An aliquot of the reaction mixture (250 μL) was removed for quantitation of the eliminated product, and the remaining liquids were removed by vacuum filtration. The resin was washed sequentially with DMF twice, CH2Cl2 twice, and DMF twice. A 20% (v/v) solution of piperidine in DMF (5 mL/g) was added to the resin, and the mixture was gently agitated for 5 min. An aliquot of the reaction mixture (250 μL) was removed for quantitation of the eliminated product, and the remaining liquids were removed by vacuum filtration. The resin was washed sequentially with DMF twice, CH2Cl2 twice, and DMF twice.

An aliquot (5 μL) from the reaction mixture was taken and diluted with MeCN (2 mL). The absorbance of the solution at 300 nm was measured in a 1-cm quartz cuvette. The concentration of the piperidine-dibenzofulvene adduct in the solution was calculated from the absorbance measurement using the reported molar absorptivity48 of 6234 M−1cm−1 at 300 nm.

Cleavage and Side-Chain Deprotection

To the resin, a mixture of TFA/iPr3SiH/H2O (95:2.5:2.5 v/v/v; 20 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was agitated for 1 h. The liquids were separated from the resin and collected by forcing the liquid phase through the peptide reaction vessel frit by positive pressure displacement with N2. The resin was washed with TFA/iPr3SiH/H2O (95:2.5:2.5 v/v/v; 2 mL) and the liquids were separated from the resin and collected by positive pressure displacement with N2. The volume of the collected liquids was reduced under a stream of N2. The mixture was precipitated into cold Et2O. The solids were separated from the liquids by centrifugation (Thermo Scientific CL10) at 3500 rpm for 5 min, and the solids were isolated by decanting the supernatant liquid. The crude peptide was precipitated from TFA into cold Et2O two more times. The solid pellet was dissolved in H2O (peptide 3) or a mixture of H2O/MeCN (9:1 v/v for peptide 2b) and lyophilized. The peptide was purified by preparative HPLC on a C18 reversed-phase column.

Imidazole-1-sulfonyl-azide hydrochloride (ISA•HCl)

The diazotransfer reagent was prepared according to a literature procedure.28 Sulfuryl chloride (7.5 mL, 92 mmol) was added dropwise to an ice-water bath-cooled suspension of NaN3 (6.00 g, 92.3 mmol) in MeCN (100 mL) and the mixture stirred overnight at room temperature. The reaction was cooled in an ice-water bath while imidazole (11.89 g, 174.7 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture and the resulting slurry stirred overnight. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (200 mL), washed with H2O (2 x 200 mL) then saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (2 x 200 mL), dried over MgSO4 and the solids were filtered in vacuo. The filtrate was cooled in an ice-water bath and a solution of HCl in EtOH60 was added dropwise while stirring. The mixture was filtered and the filter cake was washed with EtOAc to yield ISA•HCl as colorless needles (10.30 g, 54 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O, δ, ppm): 9.10 (dd, J1 = J2 =1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (dd, J1 = J2 = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (dd, J1 = J2= 1.1 Hz, 1H) 13C NMR (100 Hz, D2O, δ, ppm): 137.8, 125.6, 119.6. Spectral data agree with those previously reported.28

Assembly of Ac-YLKKLLKLLKKLLK-NH2 (3)

Resin-bound peptide 1a was assembled on ChemMatrix rink amide resin (0.50 mmol, 0.9628 g) in a glass-fritted peptide reaction vessel and cleaved from the resin to yield peptide 3. The sequence of operations is detailed in Table S1 (Supporting Information).

Synthesis of Ac-YLAnlAnlLLAnlLLAnlAnlLLAnl-NH2 (2a)

To a solution of 3 (10 mg, 0.0056 mmol), ISA•HCl (30.6 mg, 0.135 mmol), K2CO3 (13.9 mg, 0.101 mmol) and CuSO4•5H2O (8 μL, 0.25g/ mL solution, 0.0006 mmol) in THF/H2O (1:1 v/v, 5.6 mL) the reaction was adjusted to pH 10 with sat. NaHCO3 (aq) (430 μL) was stirred for 3 h at room temperature under a N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 and washed three times with EDTA (0.03 M) solution. The CH2Cl2 layer was dried over MgSO4 and the solids were removed by vacuum filtration. The resulting product was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2, CH2Cl2 to 9:1 CH2Cl2/MeOH) to yield a colorless solid.

Assembly of Ac-Y(tBu)LK(Boc)K(Alloc)LLK(Alloc)LLK(Boc)K(Alloc)LLK(Alloc)-NH-Resin (1b)

Resin-bound peptide 1b was assembled on ChemMatrix rink amide resin (0.25 mmol, 0.5510 g) in a glass-fritted peptide reaction vessel. The sequence of operations is detailed in in Table S2 (Supporting Information).

Removal of Alloc Groups

To the resin (0.1007 g), a solution of Pd(PPh3)4 (0.3001 g, 0.2592 mmol) in NMM/AcOH/CHCl3 (2.5:5:92.5 v/v/v) was added. The reaction mixture was gently agitated for 3.5 h under N2. Liquids were removed from the reaction vessel by vacuum filtration, and the resin was washed with CHCl3 (3 mL). A solution of DMF/DIEA/sodium diethyldithiocarbamate trihydrate (9:0.5:0.5 w/w/w) was added to the reaction vessel and the reaction mixture was gently agitated for 5 min. The liquids were removed from the reaction vessel by vacuum filtration, and the resin was washed with DMF. A solution of DMF/DIEA/sodium diethyldithiocarbamate trihydrate (9:0.5:0.5 w/w/w) was added to the reaction vessel and the reaction mixture was gently agitated for 5 min. The liquids were removed from the reaction vessel by vacuum filtration, and the resin was washed sequentially with DMF (3 mL) and H2O (3 mL).

On-Resin Diazotransfer Reaction Protocol

To the resin, a solution of K2CO3 (0.0580 g, 0.389 mmol) and ISA•HCl (0.1007 g, 0.5184 mmol) in of H2O (2 mL) was added, followed by CuSO4•5H2O (10 μL, 0.25 g/mL solution). The reaction mixture was gently agitated for 3 h under N2. Liquids were removed from the reaction vessel by vacuum filtration, and the resin was washed sequentially with CH2Cl2 (3 mL) twice, MeOH (3 mL) twice, and Et2O (3 mL) twice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment is made to the National Science Foundation (DMR-1255245) for support of this research. The MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of 7 was acquired by Dr. Robert Rieger (Stony Brook University Proteomics Center) on a mass spectrometer that was funded by a shared instrumentation grant (NIH/NCRR 1 S10 RR023680-1).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. A scheme and full experimental procedures describing the synthesis of 6, tables detailing the sequence of protocols for solid-phase peptide synthesis, HPLC and MALDI-TOF mass spectra of the peptides and conjugate, NMR spectra of 6 and intermediates from the synthesis of 6.

References

- 1.Johansson H, Pedersen DS. Eur J Org Chem. 2012:4267–4281. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tornøe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agard NJ, Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15046–15047. doi: 10.1021/ja044996f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saxon E, Bertozzi CR. Science. 2000;287:2007–2010. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsson BL, Kiessling LL, Raines RT. Org Lett. 2000;2:1939–1341. doi: 10.1021/ol0060174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang W, Becker ML. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:7013–7039. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00139g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramil CP, Lin Q. Chem Commun. 2013;49:11007–11022. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44272a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:6974–6998. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canalle LA, Vong T, Adams PHHM, van Delft FL, Raats JMH, Chirivi RGS, van Hest JCM. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:3692–3697. doi: 10.1021/bm2009137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Chevalier Isaad A, Barbetti F, Rovero P, D’Ursi AM, Chelli M, Chorev M, Papini AM. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:5308–5314. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres O, Yüksel D, Bernardina M, Kumar K, Bong D. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:1701–1705. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller N, Williams GM, Brimble MA. Org Lett. 2009;11:2409–2412. doi: 10.1021/ol9005536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oba M, Takazaki H, Kawabe N, Doi M, Demizu Y, Kurihara M, Kawakubo H, Nagano M, Suemune H, Tanaka M. J Org Chem. 2014;79:9125–9140. doi: 10.1021/jo501493x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bossu I, Berthet N, Dumy P, Renaudet O. J Carbohydr Chem. 2011;30:458–468. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnet R, Murat P, Spinelli N, Defrancq E. Chem Commun. 2012;48:5992–5994. doi: 10.1039/c2cc32010j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh PS, Hamilton AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:13208–13211. doi: 10.1021/ja305360q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau YH, de Andrade P, Quah ST, Rossman M, Laraia L, Sköld N, Sum TJ, Rowling PJE, Joseph TL, Verma C, Hyvönen M, Itzhaki LS, Venkitaraman AR, Brown CJ, Lane DP, Spring DR. Chem Sci. 2014;5:1804–1809. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau YH, de Andrade P, Sköld N, McKenzie GJ, Venkitaraman AR, Verma C, Lane DP, Spring DR. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:4074–4077. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00742e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawamoto SA, Coleska A, Ran X, Yi H, Yang CY, Wang S. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1137–1146. doi: 10.1021/jm201125d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blunden BM, Chapman R, Danial M, Lu H, Jolliffe KA, Perrier S, Stenzel MH. Chem - Eur J. 2014;20:12745–12749. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapman R, Warr GG, Perrier S, Jolliffe KA. Chem - Eur J. 2013;19:1955–1961. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poon CK, Chapman R, Jolliffe KA, Perrier S. Polym Chem. 2012;3:1820–1826. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman R, Jolliffe KA, Perrier S. Polym Chem. 2011;2:1956–1963. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapman R, Jolliffe KA, Perrier S. Aust J Chem. 2010;63:1169–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma D, Bettis SE, Hanson K, Minakova M, Alibabaei L, Fondrie W, Ryan DM, Papoian GA, Meyer TJ, Waters ML, Papanikolas JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:5250–5253. doi: 10.1021/ja312143h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goddard-Borger ED, Stick RV. Org Lett. 2007;9:3797–3800. doi: 10.1021/ol701581g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palomo JM. RSC Adv. 2014;4:32658–32672. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan WC, White PD, editors. Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kates SA, Albericio F, editors. Solid-Phase Synthesis: A Practical Guide. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miranda MTM, Liria CW, Remuzgo C. In: Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins in Organic Chemisty: Building Blocks, Catalysis, and Coupling Chemistry. Hughes AB, editor. Wiley-VCH; 2011. pp. 549–569. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coin I. J Pept Sci. 2010;16:223–230. doi: 10.1002/psc.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tickler AK, Wade JD. Current Protocols in Protein Science. 2007:18.18.11–18.18.16. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps1808s50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kent SBH. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:957–989. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tam JP, Lu YA. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:12058–12063. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atherton E, Woolley V, Sheppard RC. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1980:970–971. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fields GB, Fields CG. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4202–4207. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer N, Goddard-Borger ED, Greiner R, Klapötke TM, Skelton BW, Stierstorfer J. J Org Chem. 2012;77:1760–1764. doi: 10.1021/jo202264r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Dongen SFM, Teeuwen RLM, Nallani M, van Berkel SS, Cornelissen JJLM, Nolte RJM, van Hest JCM. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:20–23. doi: 10.1021/bc8004304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulbokaite R, Ciuta G, Netopilik M, Makuska R. React Funct Polym. 2009;69:771–778. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang H, Jin Y, Xue M, Yu L, Fu Q, Ke Y, Chu C, Liang X. Chem Commun. 2009:6973–6975. doi: 10.1039/b911680j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tosh DK, Yoo LS, Chinn M, Hong K, Kilbey SM, II, Barrett MO, Fricks IP, Harden TK, Gao Z-G, Jacobson KA. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:372–384. doi: 10.1021/bc900473v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen M, van Gurp THM, van Hest JCM, Löwik DWPM. Org Lett. 2012;14:2330–2333. doi: 10.1021/ol300740g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castro V, Blanco-Canosa JB, Rodriguez H, Albericio F. ACS Comb Sci. 2013;15:331–334. doi: 10.1021/co4000437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen MB, Verdurmen WPR, Leunissen EHP, Minten I, van Hest JCM, Brock R, Löwik DWPM. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:2294–2297. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeGrado WF, Lear JD. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:7684–7689. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gude M, Ryf J, White PD. Lett Pept Sci. 2002;9:203–206. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dangles O, Guibé F, Balavoine G. J Org Chem. 1987;52:4984–4993. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trzeciak A, Bannwarth W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:4557–4560. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kates SA, Solé NA, Johnson CR, Hudson D, Barany G, Albericio F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:1549–1552. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kates SA, Daniels SB, Albericio F. Anal Biochem. 1993;212:303–310. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grayson SM, Fréchet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10335–10344. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strohalm M, Kavan D, Novák P, Volný M, Havlíček V. Anal Chem. 2010;82:4648–4651. doi: 10.1021/ac100818g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strohalm M. mMass v.5.5.0. ( http://www.mmass.org/)

- 56.Cavalli S, Albericio F, Kros A. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:241–263. doi: 10.1039/b906701a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woolfson DN. Biopolymers. 2010;94:118–127. doi: 10.1002/bip.21345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bromley EHC, Channon KJ. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2011;103:231–275. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-415906-8.00001-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Branco MC, Sigano DM, Schneider JP. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.The solution of HCl in EtOH was prepared by dropwise addition of AcCl (17 mL, 240 mmol) ethanol (60 mL); the reaction vessel was cooled with an ice-water bath.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.