Abstract

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is common in the elderly, but the cause is often not identifiable. Some posit that age-related reductions in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and increases in albuminuria are normal, whereas others suggest that they are a consequence of vascular disease.

Study Design

Cross-sectional analysis of a substudy of a prospective cohort.

Setting & Participants

AGES (Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility)-Reykjavik Study.

Predictor

Exposure to higher blood pressure in midlife.

Outcomes & Measurements

Measured GFR using plasma clearance of iohexol and urine albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR).

Results

GFR was measured in 805 participants with mean age in midlife and late life of 51.0 ±5.8 and 80.8 ±4.0 (SD) years, respectively. Mean measured GFR was 62.4 ±16.5 ml/min/1.73 m2 and median albuminuria was 8.0 (IQR, 5.4–16.5) mg/g. Higher midlife systolic and diastolic blood pressures were associated with lower later life GFR. Associations persisted after adjustment. Higher midlife systolic and diastolic blood pressures were also associated with higher ACR, and associations remained significant even after adjustment.

Limitations

This is a study of survivors, and people who agreed to participate in this study were healthier than those who refused. Blood pressure may encompass effects of the other risk factors. Results may not be generalizable to populations of other races. We were not able to adjust for measured GFR or albuminuria at the midlife visit.

Conclusions

Factors other than advanced age may account for the high prevalence of CKD in the elderly. Midlife factors are potential contributing factors to late-life kidney disease. Further studies are needed to identify and treat midlife modifiable factors to prevent the development of CKD.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease (CKD), elderly, blood pressure, hypertension, measured glomerular filtration rate (mGFR), iohexol clearance, renal function, albuminuria, albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR), mid-life, aging, modifiable risk factor

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an important health problem in the elderly, with high cost and an increased risk for kidney failure, cardiovascular disease and death.1 Aging is associated with a decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and an increase in albuminuria, with a CKD prevalence of 47% for those 70 years of age and older.2 Some have suggested that the high prevalence of CKD in the elderly is secondary to normal aging3, whereas others have hypothesized that vascular disease is a major contributing factor, since CKD is commonly seen in the presence of vascular disease or its risk factors.4–12 Demonstrating that CKD is not inevitable and identifying modifiable risk factors for CKD in the elderly would have important implications for prevention.

Higher blood pressure in particular may play an important role in the development of CKD. The kidney is a highly vascular organ with high blood flow and low vascular impedance and is thus subjected to transmission of high pressures into the microcirculation where excessive pressure may cause damage. Hypertension is common in developed countries, and people with hypertension have been observed to have greater declines in kidney function with aging than those without hypertension, but these studies are limited by small sample size or absence of measured GFR (mGFR).13–16 Previous studies have documented an association of higher mid-life blood pressure with the development of end-stage renal disease in men, but not to decreased GFR per se17,18 Thus, the role of blood pressure in midlife on late life kidney disease is not well understood.

We measured GFR using plasma clearance of iohexol and albuminuria using two spot urine samples in older adults participating in the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility (AGES)-Reykjavik Study. The AGES-Reykjavik Study is a continuation of the population based prospective Reykjavik Study that has followed these participants since midlife, and as such provides a good opportunity to examine the association of midlife factors and late life disease. We hypothesized that exposure to higher blood pressure in midlife is an important determinant of lower GFR and higher albuminuria in late life.

Methods

Study Populations

The AGES-Reykjavik Study originates from the Reykjavik Study, a community-based cohort established in 1967 to prospectively study cardiovascular disease in Iceland. In 2002–2006, a total of 5764 males and females participated in detailed evaluations of cardiovascular, neurocognitive, musculoskeletal and metabolic phenotypes.19 The second visit (AGES-II-Reykjavik) was a repeat examination of 3411 participants (71% of the AGES-Reykjavik survivors) in 2007–2011. Of these, 3341 completed both visit days of the AGES-II-Reykjavik visit and were eligible for inclusion. Of the AGES-II-Reykjavik participants, 805 were enrolled in the substudy to measure GFR (AGES-Kidney). For details of selection and exclusion, please see Item S1 (provided as online supplementary material). The study was approved by the Icelandic Bioethics Committee and the institutional review boards at the National Institute on Aging and Tufts Medical Center. All participants gave written informed consent.

GFR Measurements

Details of the GFR measurement procedure can be found in Item S1. The GFR visit occurred a median of 65 (interquartile range [IQR], 32–376) days from the AGES-II-Reykjavik visit day. Five milliliters of iohexol were administered over a period of 30 seconds followed by 10 ml normal saline flush. Blood samples for plasma clearance measurements were taken from a second catheter at approximately 120, 180, 240 and 300 minutes, with the exact times recorded. Measured GFR was calculated from plasma clearance of iohexol using the Brochner-Mortensen equation20: mGFR was expressed per 1.73 m2 of body surface area.

Albuminuria Measurements

Urine samples were collected at the AGES-II-Reykjavik visit as well as on the day of GFR measurement. Where available, values from these two visits were averaged due to the known variation in albuminuria (n=793). Albuminuria was reported as albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR). For statistical analyses, ACR was log transformed due to its skewness, and parameter estimates from linear regression model were exponentiated and reported as the geometric mean ratio.

Laboratory Methods

All laboratory tests for samples obtained on the day of GFR measurement were performed at the University of Minnesota on samples frozen at −80°C. Concentration of iohexol was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (CV, 1.6%). Urine albumin was measured on a nephelometric analyzer (ProSpec, Dade Behring; CV, 3.2%). Urine creatinine was measured on a multiple analyzer (Modular P Chemistry Analyzer, Roche Diagnostics; CVs of 4.3% and 1.5% at concentrations of 18.39 and 96.57 mg/dL, respectively). Urine albumin and creatinine for urine samples collected from participants during the AGES-II-Reykjavik visit were also measured at the University of Minnesota using the aforementioned methods. All other laboratory tests performed during the Reykjavik Study or AGES-II-Reykjavik visit were performed at the Icelandic Heart Association laboratory. Serum creatinine during the Reykjavik Study was assayed on continuous flow analyzers (Technicon AutoAnalyzer I, from 1967–1986, SMA-6, from 1986–1988) and a biochemistry analyzer (Cobas-Mira, Roche) thereafter.

Variables

Other variables of interest were age at the GFR visit, blood pressure and hypertension treatment at the midlife and AGES-II-Reykjavik visit, and vascular disease risk factors and cardiovascular disease at the time of the midlife visit. For participants in the Reykjavik Study who had multiple visits, we used the midlife visit as has been used previously.21–23 At the midlife visit, hypertension was defined as blood pressure greater than 140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications; diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level greater than 126 mg/dl or random glucose level greater than 200 mg/dl or self-report of having a diagnosis of diabetes or being on a diabetic diet or medication use; hyperlipidemia was defined as total cholesterol greater than 240 mg/dl; obesity was defined as body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2; and smoking was categorized as current, past or never. Blood pressure was measured using a wall model mercury sphygmomanometer (Erkameter, Erka) after a 5 minute rest. History of cardiovascular disease was defined as prevalent coronary heart disease according to adjudicated Icelandic Heart Association registry or hospital records before the Reykjavik Study midlife visit. The GFR was estimated using the 2009 CKD-EPI (CKD Epidemiology Collaboration) creatinine equation.2

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive data were summarized using means or medians, standard deviations or ranges, p-values, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Parallel analyses were performed for the two outcomes of mGFR and albuminuria. Both mGFR and albuminuria were considered as continuous variables and categorized according to thresholds used for general populations.24 Prevalence of CKD was determined by mGFR< 60 ml/min/1.73m2 or albuminuria > 30 mg/g.25

We used linear regression to examine the relationships between the two outcomes and the variables of interest first in univariate models. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure at midlife had the strongest associations with either outcome and were selected as the key factors of interest along with age and sex. For both outcomes, we tested for nonlinearity in the functional relationship of systolic and diastolic blood pressure using parametric cubic polynomials with 4 knots using the rms package in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), with p-value of < 0.05 from the ANOVA for the nonlinear component of the cubic spline indicating evidence of nonlinearity.26 At late life, there was a nonlinear relationship with systolic blood pressure and outcomes and therefore at midlife, we also explicitly tested where a 2 slope spline with a linear knot at 140 mmHg for systolic and 80 mmHg for diastolic provides different associations than the linear model and none were seen. We checked the multiple linear regression model assumptions by examining the distribution of the standardized residuals and checked for normality using probability plots. We also used the plot of residuals vs. fitted values to check for the constant variance assumption.

For examination of the associations with midlife systolic or diastolic blood pressure, we first examined the unadjusted relationships and then adjusted the models for age, sex, serum creatinine, treatment for hypertension and vascular risk factors (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, smoking, hyperlipidemia) at the midlife visit. In other studies, stronger associations between outcomes and contemporaneous factors are more commonly observed. To investigate whether the association of midlife blood pressure and late life kidney disease persisted after adjustment for contemporaneous blood pressure measurements, we first examined the correlation coefficient between systolic and diastolic blood pressure at the two visits and then repeated the same models adjusting for blood pressure and treatment for hypertension at the AGES-II-Reykjavik visit, which were ascertained on average 65 days before the mGFR visit. Since blood pressure at the AGES-II-Reykjavik visit was not linearly associated with mGFR, we used a two slope linear spline with a knot at 140 mmHg for systolic blood pressure and 70 mmHg for diastolic blood pressure at this visit. Hypertension treatment at the AGES-II-Reykjavik was categorized into medications that block the renin angiotensin system (RAS) and those that do not. In sensitivity analyses, we examined mean arterial pressure (1/3 systolic blood pressure + 2/3 diastolic pressure) and pulse pressure (systolic blood pressure minus diastolic blood pressure). In other sensitivity analyses, we repeated the analyses using estimated GFR (eGFR) in the substudy population with mGFR (n=805) as well as in the overall AGES-II-Reykjavik study population (n=3341). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc)27 and the R package rms.26

Results

A total of 805 participants at the second visit of the AGES-Reykjavik Study (AGES-II-Reykjavik) were recruited for participation in a substudy, AGES-Kidney (Figure S1). The GFR visit occurred a median of 65 (IQR, 32–376) days from the AGES-II-Reykjavik visit day. Mean age was 80.8 ± 4.0 years. In general, at the time of the visit, participants who were included in the substudy were younger, had lower systolic blood pressure, and were less likely to be current smokers or have cardiovascular disease or diabetes than participants who were not included (Table S1). Among the participants, at midlife, mean age was 51.0 ± 5.8 years; approximately 26% had hypertension and 15% were on antihypertensive agents (Table 1 and Table S2). Between midlife and current visits, the systolic blood pressure increased and diastolic blood pressure decreased with low correlation between the two (systolic: ρ=0.14 [95% CI, 0.07–0.21]; diastolic: ρ=0.11 [95% CI, 0.03–0.17]. The proportion of participants with hypertension increased to 90% and the prevalence of cardiovascular disease and levels of vascular risk factors increased (Table S3).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of GFR cohort at midlife and late life

| Reykjavik Study (Midlife) |

AGES-ll-Reykjavik (Late life) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)* | 51 [47–55] | 80 [77–83] | <0.001 |

| Male sex* | 355(44.1) | 355(44.1) | |

| mGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2)* | -- | 62.4(16.5) | |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.0(0.4) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 85.5(12.5) | 65.7(17.0) | <0.001 |

| Urinary ACR (mg/g) | -- | 8.0 [5.4–16.5] | |

| Diabetes | 12(1.6) | 90(11.8) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 318(41.7) | 291 (39.1) | |

| Past | 216(28.4) | 411 (55.2) | |

| Current | 228 (29.9) | 43 (5.8) | |

| Obesity | 76(10.0) | 170(22.3) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 358 (47.0) | 476 (62.5) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 6 (0.8) | 227 (29.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 197(25.9) | 684 (89.9) | <0.001 |

| No CVD or vascular disease risk factors | 118(15.5) | 11 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 129.4(15.2) | 142.5(20.3) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 82.3(9.1) | 69.6(10.7) | <0.001 |

| On treatment for hypertension | 115(15.1) | 564 (74.0) | <0.001 |

| RAS blockers | -- | 308 (40.4) | |

| Other medications | -- | 256 (33.6) | |

| None | -- | 198(26.0) |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage); values for continuous variables, as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. Conversion factors for units: creatinine in mg/dL to µmol/L, ×88.4; GFR in mL/min/1.73 m2 to mL/s/m2, ×0.0167; ACR in mg/g to mg/mmol, ×0.113 eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; CVD, cardiovascular disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; RS, Reykjavik Study; AGES-ll-Reykjavik, Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility Reykjavik Study, second visit; RAS, renin angiotensin system; mGFR, measured glomerular filtration rate

Total N in these rows is 805. For other rows, total N is 762

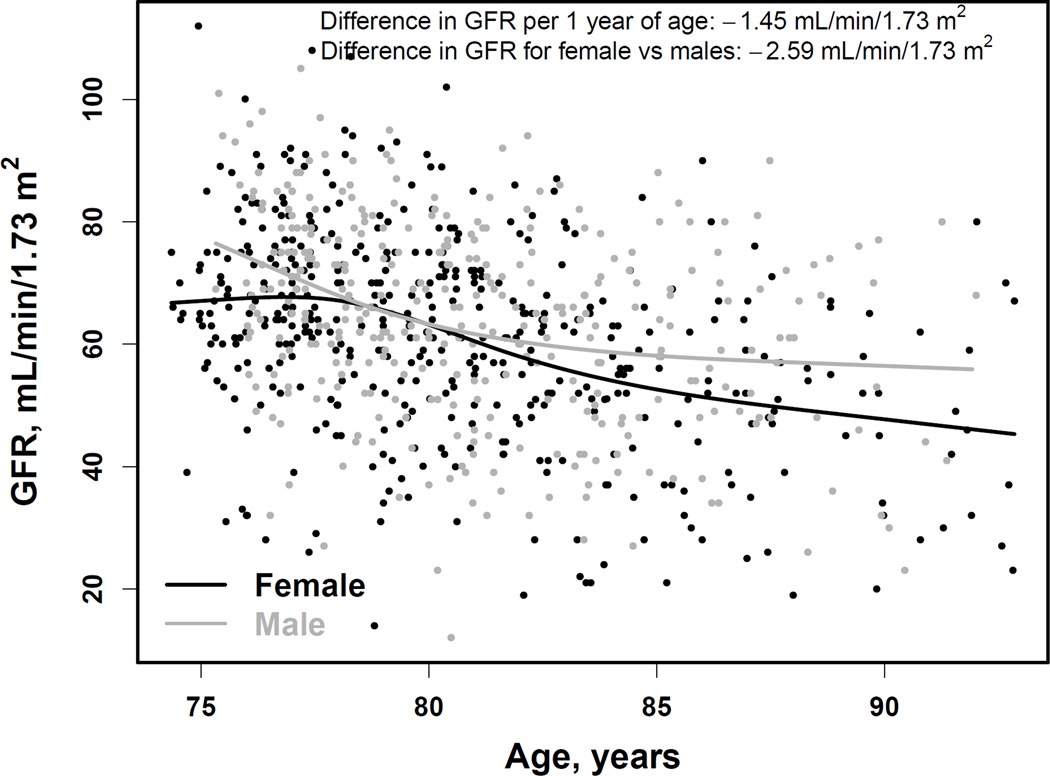

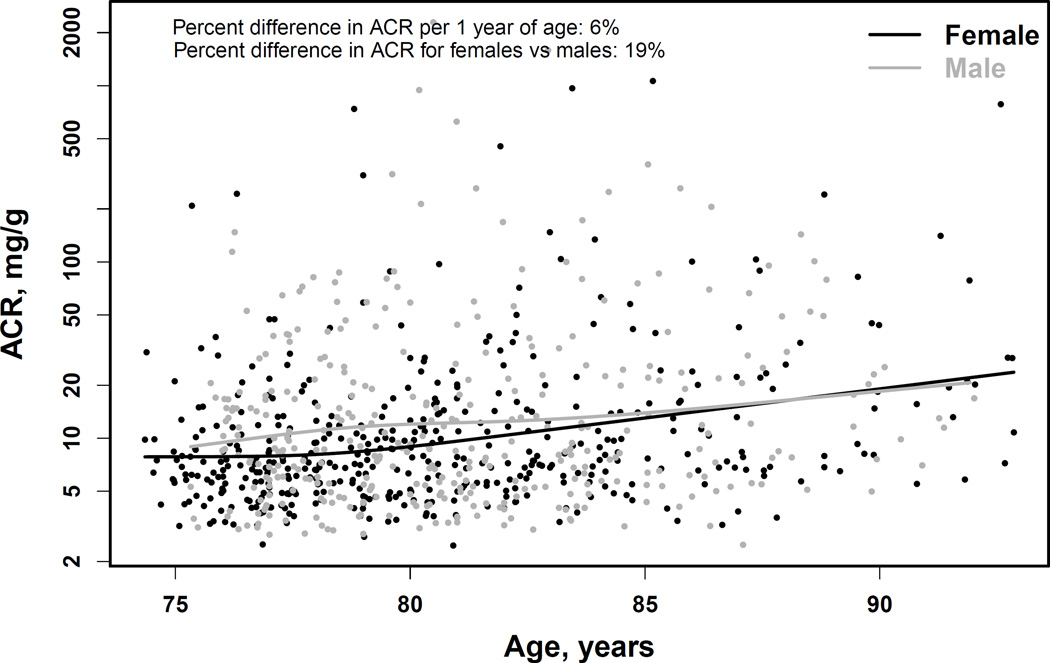

In AGES-Kidney, the mean mGFR was 62.4 ±16.5 (range, 12–112) ml/min/1.73m2 (Table 1). A total of 314 (39.0%; 95% CI, 35.6%-42.5%) had mGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 (Table 2). Median albuminuria was 8.0 (IQR, 5.4–16.5) mg/g (Table 1), and 111 participants (13.8%; 95% CI, 11.5%-16.4%) had ACR > 30 mg/g (Table 2). Overall, the prevalence of CKD was 45.7% (95% CI, 42.2%-49.2%) (Table 2). The mGFR in late life was significantly related to age (R2 =13%; p < 0.001) (Figure 1, top panel). A 1.0-year-older age was associated with a 1.45 (95% CI, 1.19–1.72) ml/min/1.73 m2 lower mean mGFR. Women had a 2.59 (95% CI, 0.31–4.88) ml/min/1.73 m2 lower mean mGFR than men, which persisted after adjustment for age. Albuminuria in late life was also related to age (R2 =4.4%; p=0.004)(Figure 1, bottom panel). A 1.0-year-older age was associated with a 5.7% (95% CI, 3.9%-7.6%) higher ACR. Women had 19.3% (95% CI, 6.8%-30.1%) lower ACR than men, which persisted after adjustment for age.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Albuminuria and GFR Categories

| GFR Categories |

Albuminuria Categories | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACR < 10 | ACR 10-<30 | ACR 30-<300 | ACR ≥ 300 | ||

| GFR ≥ 90 | 22 (2.7) | 9 (1.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 33 (4.1; 2.8–5.7]) |

| GFR 60 -<90 | 290 (36) | 116 (14.4) | 48 (6.0) | 4 (0.5) | 458 (56.9; 53.4–60.3) |

| GFR 45 - <60 | 116 (14.4) | 57 (7.1) | 23 (2.9) | 1 (0.1) | 197 (24.5; 21.5–27.6) |

| GFR 30 - <45 | 43 (5.3) | 25 (3.1) | 19 (2.4) | 2 (0.2) | 89 (11.1; 9.0–13.4) |

| GFR < 30 | 12 (1.5) | 4 (0.5) | 7 (0.9) | 5 (0.6) | 28 (3.5; 2.3–5.0) |

| Total | 483 (60.0; 56.5–63.4) | 211 (26.2; 23.2–29.4) | 99 (12.3; 10.1–14.8) | 12 (1.5; 0.8–2.6) | 805 (100) |

Note: Values are given as number (percentage), with row and column totals also showing 95% CIs on proportion. GFR expressed as ml/min/1.73m2 and ACR expressed as mg/g. Shaded area represents participants with chronic kidney disease, 368 (45.7%; 95% CI, 42.2%-49.2%). Conversion factor for ACR in mg/g to mg/mmol, ×0.113.

ACR, urinary albumin-creatine ratio; CI, confidence interval; Glomerular filtration rate, GFR;

Figure 1. Association of age with measured GFR (top panel) and albuminuria (bottom panel).

Curves are restricted cubic splines with four knots at the default percentiles locations (5%, 35%, 65% and 95%) from the rms package of the R software. These translate to age of 76, 79, 82 and 88 years for men and 75, 78, 82 and 89 years for women. GFR, glomerular filtration rate (in ml/min/1.73m2). ACR, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (in mg/g).

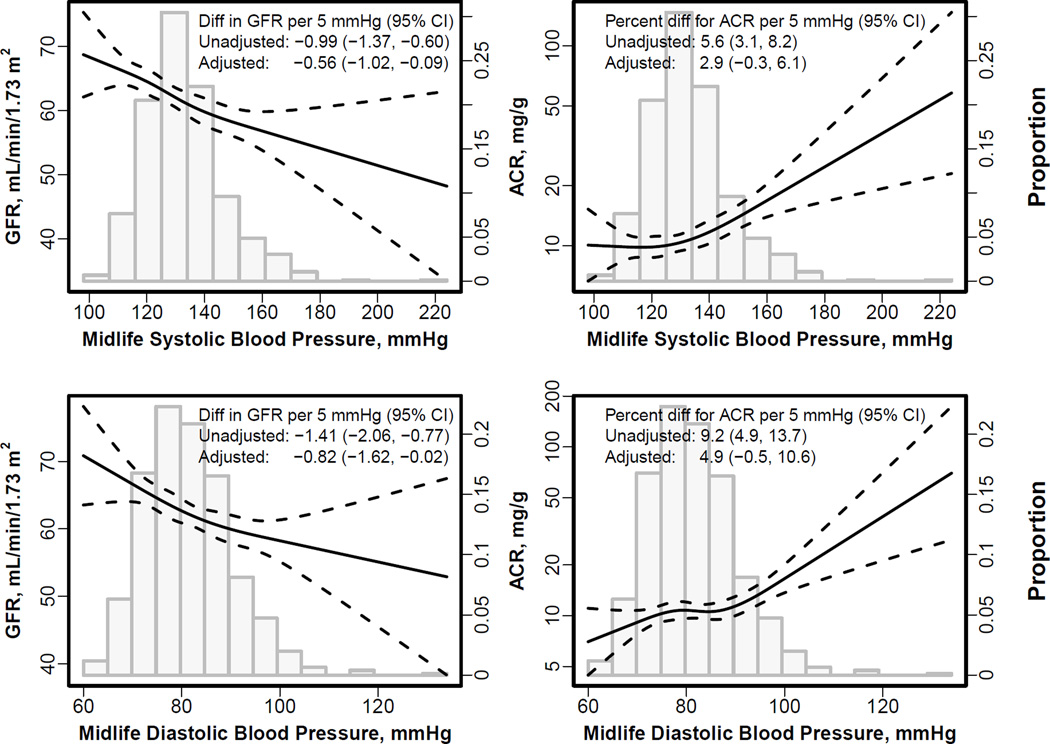

The mGFR at late life was lower in participants with vs without midlife hypertension (59.8 [95% CI, 55.6–60.6] mL/min/1.73 m2 vs 63.9 [95% CI, 62.6–65.2] mL/min/1.73 m2; Figure S2). There was a negative linear association between higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure at the midlife visit with lower late life mGFR (−0.99 [95% CI, −1.37 to −0.60) and −1.41 [95% CI, −2.06 to −0.77] ml/min/1.73 m2 per 5.0 mmHg, respectively; p<0.001 for both; Table 3). The associations with midlife systolic and diastolic blood pressure were attenuated but remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, creatinine, other vascular risk factors, and treatment for hypertension at midlife (Figure 2, Table 3). The associations with midlife systolic and diastolic blood pressure and late life mGFR persisted after adjustment for contemporaneous blood pressure, but were attenuated and no longer significant after adjustment for contemporaneous hypertension treatment. In sensitivity analyses, results were similar using either mean arterial blood pressure or pulse pressure as the exposure variables (Table S3). In further sensitivity analyses, results were similar using eGFR in the substudy population with mGFR (n=805) as well as in the overall AGES II study population (n=3411) after adjustment for age and sex (Table S4), or despite whether eGFR at midlife instead of serum creatinine was used to adjust for midlife kidney function.

Table 3.

Associations of blood pressure at midlife with late life mGFR and albuminuria

| Model | mGFR β (95% CI)^ |

Albuminuria GMR (95% CI)^ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midlife SBP | Midlife DBP | Midlife SBP | Midlife DBP | |

| Unadjusted | −0.99 (−1.37, −0.60) | −1.41 (−2.06, −0.77) | 1.06 (1.03, 1.08) | 1.09 (1.05, 1.14) |

| Midlife | ||||

| Age, sex and creatinine | 0.59 (−0.95, −0.23) | −0.91 (−1.52, −0.29) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.07) | 1.06 (1.02, 1.11) |

| +hypertension treatment | −0.63 (−1.08, −0.17) | −0.92 (−1.70, −0.13) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 1.06 (1.00, 1.12) |

| +vascular risk factors | −0.57 (−1.03, −0.11) | −0.83 (−1.63, −0.03) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.12) |

| Late life | ||||

| +blood pressurea | −0.56 (−1.02, −0.09) | −0.82 (−1.62, −0.02) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) |

| +hypertension treatment | −0.10 (−0.57, 0.37) | −0.05 (−0.85, 0.76) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) |

Note: Bold indicates association’s significance at p-value of < 0.05. At the midlife visit, hypertension was defined as blood pressure greater than 140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications; diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level greater than 126 mg/dl or random glucose level greater than 200 mg/dl or self-report of having a diagnosis of diabetes or being on a diabetic diet or medication use; hyperlipidemia was defined as total cholesterol greater than 240 mg/dl; obesity was defined as body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2, and smoking was categorized as current, past or never. Blood pressure was measured using a wall model mercury sphygmomanometer after a 5 minute rest. History of cardiovascular disease was defined as prevalent coronary heart disease according to adjudicated Icelandic Heart Association registry or hospital records before the Reykjavik Study midlife visit.

CI, confidence interval; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GMR, geometric mean ratio; mGFR, measured glomerular filtration rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure

systolic or diastolic blood pressure were used for adjustment, and would be the same as used in midlife.

β and GMR are per 5 mmHg higher systolic or diastolic blood pressure

Figure 2. Spline curve for association of midlife and change in systolic and diastolic blood pressure with late life measured GFR and albuminuria.

GFR, glomerular filtration rate. ACR, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio. The two left plots show the associations of systolic (top) and diastolic (bottom) blood pressure with measured GFR. The two right panels show the associations of systolic (top) and diastolic (bottom) blood pressure with albuminuria. The histogram shows the distribution of midlife systolic (top two panels) and diastolic blood pressure (bottom two panels). Albuminuria is expressed as percentage change. Curves are restricted cubic splines with four knots at the default percentiles locations (5%, 35%, 65% and 95%) from the rms package of the R software. These translate to 100, 122, 133, and 157 mm Hg for systolic blood pressure and 70, 79, 85, 99 mm Hg for diastolic blood pressure. There was no statistical evidence of nonlinearity for all relationships. Adjusted values are for the midlife blood pressure were adjusted for age, sex, serum creatinine at midlife, hypertension at midlife, and contemporaneous blood pressure

There was a positive linear association between higher midlife systolic and diastolic blood pressure and higher ACR at late life: for each 5 mm Hg higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure, respectively, ACR was greater by 5.6% [95% CI, 3.1%-8.2%] and 9.2% [95% CI, 4.9%-13.7%][p<0.001 for both]. The association remained significant with little attenuation after adjusting for midlife factors (Figure 2 and Table 3). The associations between midlife systolic and diastolic blood pressure and late life ACR was of the same magnitude after adjustment for contemporaneous blood pressure, although became nonsignificant, and then weakened substantially after adjustment for hypertension treatment. In sensitivity analyses, results using either mean arterial blood pressure or pulse pressure were similar (Table S3). Results were similar in the overall AGES-II-Reykjavik population (Table S5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study in the elderly with measurement of GFR and albuminuria and prospectively collected information on kidney function and risk factors from midlife. We found a high prevalence of CKD, with a strong association of lower mGFR and higher albuminuria with older age, although there were wide ranges of mGFR and albuminuria values at all ages. In addition, independent of age and mid-life kidney function, higher levels of mid-life systolic and diastolic blood pressure were associated with mGFR and also albuminuria observed nearly 30 years later. These results support the notion that age-related decline in GFR and increase in albuminuria are related, in part, to modifiable factors rather than to age alone.

Prior studies examining the prevalence of CKD in the general population either used eGFR, or did not include sufficient number of elderly from a community-based sample.28–34 Our results are similar to prevalence estimates in the elderly in the United States using eGFR and provide some validation for this practice of estimating CKD prevalence and risk associations2. The wide variation in level of mGFR and albuminuria we observed is consistent with autopsy findings of older adults that showed variation in the presence of pathological changes including global glomerulosclerosis, vascular sclerosis, and tubular atrophy together with reduced cortical thickness and decreased kidney size.35–38 Consistent with our findings, the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging showed that only a third of participants had a decline in measured creatinine clearance over time.14,15 Although we observed that age was a correlate of late-life mGFR and albuminuria, and stronger than blood pressure, aging is associated with development and worsening of multiple comorbid conditions that are considered to be risk factors for vascular and kidney disease. Thus, it is difficult to distinguish the contribution of these factors vs. aging per se to lower GFR and higher albuminuria. Indeed, the small number of participants without any risk factors or CVD throughout the life course does not allow us to investigate the change of GFR with age in the absence of such factors.

The associations of systolic and diastolic blood pressures with late life kidney function and damage were attenuated but persisted even after adjustment for other midlife factors and contemporaneous blood pressure. However, the associations were attenuated and became nonsignificant after adjustment for contemporaneous hypertension treatment. The change in the strength of the association is due to several factors. First, late-life hypertension treatment is consequent to midlife blood pressure. Second and more importantly, attenuation after adjustment for late life treatment may also reflect “indication bias”—people with lower levels of GFR and higher levels of albuminuria are more likely to receive antihypertensive agents for treatment of kidney or cardiovascular disease. Of interest, the mean mGFR was not substantially lower in people receiving RAS blockers vs. other antihypertensive agents, suggesting that the lower GFR was not simply related to renal hemodynamic effects of RAS blockers. These findings underscore the difficulty in assigning determinants of late life lower GFR and higher albuminuria in the absence of knowledge of midlife factors.

These results have several implications. First, our observation of the association of lower GFR and higher albuminuria in late life with midlife factors in addition to age, raises the hypothesis that CKD in the elderly may be in part preventable. We observed a rise in systolic blood pressure and a decline in diastolic blood pressure over time, a phenomenon that has been attributed to age-related increase in aortic stiffness.39 Previous studies in large community based cohorts of middle aged persons showed that aortic stiffness was associated with higher risk of incident hypertension, but not the converse, suggesting that measures to prevent aortic stiffness may also prevent late life kidney disease.39 At present there is little known about how to reverse arterial stiffness, but this may be an area of exploration. Second, the findings suggest that future research as to appropriate targets for blood pressure especially in younger ages is needed. Recent guidelines for management of hypertension recommend initiation of treatment for high blood pressure for people younger than 60 years at blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg, however the recommendations are based on expert opinion for systolic blood pressure and expert opinion on diastolic blood pressure for people younger than 30 years, and kidney disease was not well evaluated in most studies reviewed.13 Recent and ongoing large trials to test lower blood pressure targets have enrolled older, high risk individuals, and therefore may not be applicable to lower risk or younger people.40,41 A recent study showed that younger adults were less likely than older adults to receive anti-hypertensive treatment, suggesting that greater awareness of the importance of earlier life blood pressure is needed.42 Prior studies suggest that public health strategies such as dietary modifications (e.g. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet, lower dietary salt intake, increased intake of potassium and fruits and vegetables, smoking) and weight loss in overweight people may be effective; and statins may be worthwhile to prevent the development of hypertension or aortic stiffness, and which in turn may lead to prevention of kidney disease, but this requires explicit evaluation.43,44,45,46

The strengths of this study include measurement of GFR using the reference standard method in a well characterized cohort of the elderly. The use of mGFR, rather than eGFR, is unique and avoids confounding by non-GFR determinants of endogenous filtration markers, such as muscle mass for creatinine and fat mass for cystatin C. Use of plasma clearance avoids any concerns about the adequacy of urine collection or urinary retention, which may be expected in the elderly. Similarity of the Icelandic population to other European and North American countries with respect to its vascular risk factor profile supports the generalizability of these results.47,48 The presence of the midlife data on blood pressure and serum creatinine allows for stronger inferences about causality.

There are also several limitations. Most important, studies of the elderly are by definition studies of survivors, and we cannot comment on the importance of midlife blood pressures for people who did not survive. It is possible that we have not understood correctly the strength of the association between midlife blood pressure and late life GFR and albuminuria because people with the highest midlife blood pressures may have died prior to the late life visit. Yet, since the question concerns CKD in older adults, the findings are relevant for understanding the development of CKD in this segment of the population. Previous studies have used similar strategies to examine associations with midlife factors.49 Second, of the surviving participants, the people who agreed to participate in this study were healthier than people who refused, although this too would underestimate the strength of the association. Third, blood pressures were taken at one time point, and were not on the same day as the GFR measurement, occurring on average 65 days earlier. However, these measurements have been used in other publications and have shown to be informative.50,51 Fourth, blood pressure may be capturing effects of the other risk factors. In particular, possibly higher mid-life blood pressure is due to lower mid-life kidney function, as indicated by higher serum creatinine, which worsens over time. Fifth, our results may not be generalizable to populations of other races, specifically those with higher prevalence of diabetes at midlife. Sixth, we were not able to adjust for mGFR or albuminuria at the midlife visit and finally, we only have one measurement of GFR at late life.

In conclusion, we found wide variation in mGFR and albuminuria in a population-based cohort, suggesting that factors other than advanced age may account for the high prevalence of CKD in the elderly. The significant associations of higher midlife systolic and diastolic blood pressure with lower late-life GFR and higher albuminuria suggests the importance of midlife factors as a potential contributing factor of late life kidney disease, and offers possible strategies for prevention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Preliminary results of this research were presented in abstract form at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Nephrology, November 8, 2013, Atlanta, GA.

Support: This study was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health (NIH; R01 DK082447), a contract from the National Institute on Aging (N01-AG-1–2100), Hjartavernd (Icelandic Heart Association), and the Icelandic Parliament (Althingi). The Icelandic Heart Association provided support for data collection. The funding sources did not have any role in study design; analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Financial Disclosure: Lesley Inker reports funding to Tufts Medical Center for research and contracts with the NIH, National Kidney Foundation, Pharmalink AB and Gilead Sciences, a consulting agreement with Otsuka, and has a provisional patent [Coresh, Inker and Levey] filed 8/15/2014 -- Precise estimation of glomerular filtration rate from multiple biomarkers (licensing under negotiations). Gary Mitchell is owner of Cardiovascular Engineering Inc, a company that develops and manufactures devices to measure vascular stiffness; serves as a consultant to and receives honoraria from Novartis and Merck; and is funded by research grants from the NIH. Andrew Levey reports funding to Tufts Medical Center for research and contracts with the NIH, National Kidney Foundation, Amgen, Pharmalink AB, and Gilead Sciences, and has a provisional patent [Coresh, Inker and Levey] filed 8/15/2014 -- Precise estimation of glomerular filtration rate from multiple biomarkers (licensing under negotiations). Tamara Harris and Lenore Launer work for the National Institute on Aging. The other authors declare that they have no other relevants financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributions: Research area and study design: LAI, ASL; data acquisition: LAI, AO, MBA, GE, HG, VG, OI, GM, HN, RP, JES, ASL; data analysis/interpretation: LAI, HT, MBA, TA, HG, VG, TH, OI, LL, GM, FN, RP, ASL; statistical analysis: LAI, HT, FN, ASL; funding obtainment: LAI, ASL; administrative, technical, or material support: LAI, AO, GE, VG, TH, LL, HN, RP, JES, MBA, HG, VG, OI, ASL; supervision or mentorship: LAI, GE, VG, TH, LL, RP, ASL. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. LAI takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Table S1: Clinical characteristics of AGES-II-Reykjavik participants at second visit.

Table S2: Clinical characteristics at midlife and late life, overall and by age category.

Table S3: Associations of midlife mean arterial BP and pulse pressure at midlife with late-life mGFR and albuminuria.

Table S4: Associations of BP at midlife with late-life eGFR, in mGFR subcohort and overall.

Table S5: Associations of BP at midlife with late-life albuminuria.

Figure S1: AGES-Kidney GFR study participant recruitment.

Figure S2: mGFR at late life, by midlife hypertension status.

Item S1: Supplemental methods.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi: _______ ) is available at www.ajkd.org

Descriptive Text for Online Delivery of Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1 (PDF)

Clinical characteristics of AGES-II-Reykjavik participants at second visit.

Supplementary Table S2 (PDF)

Clinical characteristics at midlife and late life, overall and by age category.

Supplementary Table S3 (PDF)

Associations of midlife mean arterial BP and pulse pressure at midlife with late-life mGFR and albuminuria.

Supplementary Table S4 (PDF)

Associations of BP at midlife with late-life eGFR, in mGFR subcohort and overall.

Supplementary Table S5 (PDF)

Associations of BP at midlife with late-life albuminuria.

Supplementary Figure S1 (PDF)

AGES-Kidney GFR study participant recruitment.

Supplementary Figure S2 (PDF)

mGFR at late life, by midlife hypertension status.

Supplementary Item S1 (PDF)

Supplemental methods.

References

- 1.Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9811):165–180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckardt KU, Berns JS, Rocco MV, Kasiske BL. Definition and classification of CKD: the debate should be about patient prognosis--a position statement from KDOQI and KDIGO. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):915–920. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarnak MJ, Katz R, Stehman-Breen CO, et al. Cystatin C concentration as a risk factor for heart failure in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):497–505. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Katz R, et al. Cystatin C and the risk of death and cardiovascular events among elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(20):2049–2060. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried LF, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, et al. Kidney function as a predictor of noncardiovascular mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(12):3728–3735. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005040384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Hare AM, Newman AB, Katz R, et al. Cystatin C and incident peripheral arterial disease events in the elderly: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2666–2670. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shlipak MG, Katz R, Fried LF, et al. Cystatin-C and mortality in elderly persons with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(2):268–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manjunath G, Tighiouart H, Coresh J, et al. Level of kidney function as a risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes in the elderly. Kidney Int. 2003;63(3):1121–1129. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH. Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(6):659–663. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Crump C, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk status in elderly persons with renal insufficiency. Kidney Int. 2002;62(3):997–1004. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindeman RD, Tobin JD, Shock NW. Association between blood pressure and the rate of decline in renal function with age. Kidney Int. 1984;26(6):861–868. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindeman RD, Tobin J, Shock NW. Longitudinal studies on the rate of decline in renal function with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33(4):278–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb07117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fliser D, Franek E, Joest M, Block S, Mutschler E, Ritz E. Renal function in the elderly: impact of hypertension and cardiac function. Kidney Int. 1997;51(4):1196–1204. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Randall BL, et al. Blood pressure and end-stage renal disease in men. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(1):13–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601043340103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds K, Gu D, Muntner P, et al. A population-based, prospective study of blood pressure and risk for end-stage renal disease in China. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(6):1928–1935. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G, et al. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(9):1076–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brochner-Mortensen J. A simple method for the determination of glomerular filtration rate. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1972;30(3):271–274. doi: 10.3109/00365517209084290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scher AI, Gudmundsson LS, Sigurdsson S, et al. Migraine headache in middle age and late-life brain infarcts. JAMA. 2009;301(24):2563–2570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang M, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J, et al. The effect of midlife physical activity on cognitive function among older adults: AGES--Reykjavik Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(12):1369–1374. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Bonsdorff MB, Muller M, Aspelund T, et al. Persistence of the effect of birth size on dysglycaemia and type 2 diabetes in old age: AGES-Reykjavik Study. Age (Dordr) 2013;35(4):1401–1409. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9427-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2073–2081. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1):136–150. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrell FE., Jr rms: Regression Modeling Strategies. [Accessed March 10, 2014];R package version 3.6–0. 2012 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rms.

- 27.SAS/STAT® 9.3 User’s Guide. [computer program] Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies DF, Shock NW. Age changes in glomerular filtration rate, effective renal plasma flow, and tubular excretory capacity in adult males. J Clin Invest. 1950;29(5):496–507. doi: 10.1172/JCI102286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Amin MG, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a pooled analysis of community-based studies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(5):1307–1315. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000123691.46138.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verhave JC, Gansevoort RT, Hillege HL, De Zeeuw D, Curhan GC, De Jong PE. Drawbacks of the use of indirect estimates of renal function to evaluate the effect of risk factors on renal function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(5):1316–1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksen BO, Mathisen UD, Melsom T, et al. The role of cystatin C in improving GFR estimation in the general population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(1):32–40. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathisen UD, Melsom T, Ingebretsen OC, et al. Estimated GFR associates with cardiovascular risk factors independently of measured GFR. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(5):927–937. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delanaye P, Cavalier E, Moranne O, Lutteri L, Krzesinski JM, Bruyere O. Creatinine-or cystatin C-based equations to estimate glomerular filtration in the general population: impact on the epidemiology of chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Pottelbergh G, Den Elzen WP, Degryse J, Gussekloo J. Prediction of mortality and functional decline by changes in eGFR in the very elderly: the Leiden 85-plus study. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindeman RD. Overview: renal physiology and pathophysiology of aging. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990;16(4):275–282. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasiske BL. Relationship between vascular disease and age-associated changes in the human kidney. Kidney Int. 1987;31(5):1153–1159. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson S, Brenner BM. Effects of aging on the renal glomerulus. Am J Med. 1986;80(3):435–442. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rule AD, Amer H, Cornell LD, et al. The association between age and nephrosclerosis on renal biopsy among healthy adults. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(9):561–567. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaess BM, Rong J, Larson MG, et al. Aortic stiffness, blood pressure progression, and incident hypertension. JAMA. 2012;308(9):875–881. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) [Accessed October 16, 2013]; https://www.sprinttrial.org/public/dspHome.cfm.

- 41.Group AS, Cushman WC, Evans GW, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson HM, Thorpe CT, Bartels CM, et al. Antihypertensive medication initiation among young adults with regular primary care use. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):723–731. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2790-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, et al. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2006;24(2):215–233. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000199800.72563.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA. Effect of longer-term modest salt reduction on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD004937. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004937.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Committee on Public Health Priorities to Reduce and Control Hypertension in the U.S. Population; Institute of Medicine. A Population-Based Policy and Systems Change Approach to Prevent and Control Hypertension. The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukherjee D. Atherogenic vascular stiffness and hypertension: Cause or effect? JAMA. 2012;308(9):919–920. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vilbergsson S, Sigurdsson G, Sigvaldason H, Hreidarsson AB, Sigfusson N. Prevalence and incidence of NIDDM in Iceland: evidence for stable incidence among males and females 1967–1991--the Reykjavik Study. Diabet Med. 1997;14(6):491–498. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199706)14:6<491::AID-DIA365>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thrainsdottir IS, Aspelund T, Thorgeirsson G, et al. The association between glucose abnormalities and heart failure in the population-based Reykjavik study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(3):612–616. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fox CS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Culleton B, Wilson PW, Levy D. Predictors of new-onset kidney disease in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;291(7):844–850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.7.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gudmundsson LS, Johannsson M, Thorgeirsson G, Sigfusson N, Sigvaldason H, Witteman JC. Risk profiles and prognosis of treated and untreated hypertensive men and women in a population-based longitudinal study: the Reykjavik Study. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18(9):615–622. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide. Association S, Ehret GB, Munroe PB, et al. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011;478(7367):103–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.