Abstract

Serratia entomophila and Serratia proteamaculans (Enterobacteriaceae) cause amber disease in the grass grub Costelytra zealandica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae), an important pasture pest in New Zealand. Larval disease symptoms include cessation of feeding, clearance of the gut, amber coloration, and eventual death. A 155-kb plasmid, pADAP, carries the genes sepA, sepB, and sepC, which are essential for production of amber disease symptoms. Transposon insertions in any of the sep genes in pADAP abolish gut clearance but not cessation of feeding, indicating the presence of an antifeeding gene(s) elsewhere on pADAP. Based on deletion analysis of pADAP and subsequent sequence data, a 47-kb clone was constructed, which when placed in either an Escherichia coli or a Serratia background exerted strong antifeeding activity and often led to rapid death of the infected grass grub larvae. Sequence data show that the antifeeding component is part of a large gene cluster that may form a defective prophage and that six potential members of this prophage are present in Photorhabdus luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1, a species which also has sep gene homologues.

Serratia entomophila and Serratia proteamaculans (Enterobacteriaceae) are the causal agents of amber disease of the New Zealand grass grub Costelytra zealandica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). The disease was first described by Trought et al. (47), and S. entomophila was subsequently developed into a commercially available biopesticide for C. zealandica in New Zealand (25). The disease is highly host specific, affecting only larvae of a single species of New Zealand scarab. The disease has a distinct progression. Infected larvae cease feeding within 1 to 3 days of ingesting pathogenic cells. The bacteria colonize the digestive tract. The gut, which is normally dark in color, clears (27), and the levels of the major gut protease digestive enzymes, such as trypsin, decrease sharply (28). The clearance of the gut results in a characteristic amber color of the infected hosts. The larvae may remain in this state for a prolonged period (1 to 3 months) before bacteria eventually invade the haemocoel, resulting in rapid death of the larvae (29).

Plasmids have been implicated in many human diseases, such as those caused by Yersinia pestis (20) and Salmonella spp. (17). The insecticidal toxins of Bacillus thuringiensis are also often plasmid borne (19). Glare et al. (13) demonstrated that a plasmid, designated pADAP (for amber disease-associated plasmid), was involved in the virulence of S. entomophila against grass grub larvae, as plasmid-cured strains lost virulence. Hurst et al. (23) isolated a 23-kb pADAP BamHI clone (designated pBM32) that in either E. coli or a pADAP-cured strain of S. entomophila conferred both gut clearance and antifeeding activity. Sequence analysis of this virulence-encoding region showed that the predicted products of three of the open reading frames (ORFs) (sepA, sepB, and sepC) had significant sequence similarity to components of the insecticidal toxins produced by the bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens (8) and another nematode-associated bacterium, Xenorhabdus nematophilus (34).

Previous studies showed that mutation of sepA, sepB, or sepC abolished the virulence of the pBM32 clone when expressed in E. coli or pADAP-cured S. entomophila. When these sep-based mutations were recombined into pADAP, the resulting bacteria still caused antifeeding but did not cause the gut clearance typical of amber disease (23). This suggests that an additional antifeeding gene(s) may be present elsewhere on pADAP. The occurrence of two different antifeeding genes on pADAP supports dose-response data of Grkovic et al. (15), who found that suppression of feeding was stronger in the wild-type pADK-6 strain than in strains harboring the mutated pADAP derivatives pADK-10 (::sepB) or pADK-13 (::sepC). In this report, we describe the identification, cloning, mutagenesis, and nucleotide sequence analysis of the pADAP antifeeding-encoding region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and methods of culture.

Table 1 lists the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study. Bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani broth or on Luria-Bertani agar (40) at 37°C for Escherichia coli and 30°C for S. entomophila. For Serratia, the antibiotics kanamycin, chloramphenicol, spectinomycin, and tetracycline were used at 100, 90, 100, and 30 μg/ml, respectively. For E. coli, kanamycin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and ampicillin were used at 50, 30, 15, and 100 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and bacteriophage used in the study

| Bacterial strains and plasmids | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DHB101 | F−mcrA Δmrr-hsdRMS-mcrBCφ80d lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 endA1 recA 1 deoR Δ(ara-leu)7697 araD139 galU galK nupG rpsl λ− | 33 |

| MC1061 | supohsdR mcrB araD139 ΔaraABC-leu7679 ΔlacX74 galU galK rpsL thi | 42 |

| XL1-BlueMRA | ΔmcrA183 ΔmcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 reA1 gyrA96 relA1 | Stratagene |

| S. entomophila | ||

| A1MO2 | pADAP pathogenic | 14 |

| 5.6RK | KnrrecA pADAP-minus strain | 23 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pADAP | Amber disease-associated plasmid (155 kb) | 13 |

| pADK-13 | Knr pADAP::mini-Tn10 insertion in SepC | 15 |

| pBR322 | Apr Tcr | 7 |

| pAF6 | Apr antifeeding prophage-encoding region in pBRminicosAvrII | This study |

| pAF6-1-32 | Apr Cmr pAF6 containing mini-Tn10 insertions | This study |

| pLAFR3 | Tcr pRK290 with λcos lacZ and multicloning site from pUC8 | 43 |

| pNK2859 | Knr mini-Tn10 derivative 103 | 32 |

| pMH52 | Tcr 25-kb HindIII fragment of pADAP cloned into pLAFR3 | 22 |

| pMH53 | Tcr 26-kb HindIII fragment of pADAP cloned into pLAFR3 | 22 |

| pMH54 | Tcr 19-kb HindIII fragment of pADAP cloned into pLAFR3 | 22 |

| pMH52ΔBg1II | Tcr Knr HindIII-derived fragment from pUC52ΔBglIIKn in HindIII site of pLAFR3 | This study |

| pBRminicos | Apr pBR322 containing pLAFR3-derived BglII cos site inserted into its BamHI site | This study |

| pBRminicosUH5.4 | Apr pBRminicos1 containing pUH5.4 HindIII fragment | This study |

| pBRminicosAvrII | Apr EcoRI self-ligated pBRminicosUH5.4 containing unique AvrII restriction enzyme site | This study |

| pHSG398 | CmrlacZ multicloning site | 45 |

| pUC19 | AprlacZ multicloning site | 51 |

| pUH5.4 | Cmr 5.2-kb HindIII fragment inserted into the HindIII site of pHSG398 | 24 |

| pUC52 | Apr 25-kb HindIII fragment of pMH52 cloned into pUC19 | This study |

| pUC52ΔBglIIKn | Apr Knr BglII-digested self-ligated pUC52 containing BamHI Knr mini-Tn10 derivative 103 fragment in its BglII site | This study |

| pAD32ΔBglII | Knr 11.2-kb pADAP deletion spanning the BglII site of pBM32 (143.8 kb) | 22 |

| pADK93XbaIΔ14XbaI | Knr 30-kb pADAP deletion spanning the XbaI site of pGLA93 to the XbaI site of pAF6 (125 kb) | 22 |

| pADC20XbaIΔStuI | Cmr 25-kb pADAP deletion spanning the XbaI site of pGLA20 to the StuI site of pMH20 (130 kb) | 22 |

| pADK93XbaIΔStuI | Spr 33.8-kb pADAP deletion spanning the XbaI site of pGLA93 to the StuI site of pMH20 (121.2 kb) | 22 |

| pADS93XbaIΔStuIΔ-BglIIKn | Spr Knr 16-kb pADK93XbaIΔStuI deletion spanning the BglII sites internal to pMH52 (105.2 kb) | This study |

| Bacteriophage | ||

| λNK1324 | Mini-Tn10 derivative 105 donor λb522 c1857 Pam80 nin5 | 32 |

Mutagenesis and bioassays.

Transposon insertions were generated in recombinant plasmids using the mini-Tn10 derivative 105 (chloramphenicol resistant) carried on λNK1324, as described by Kleckner et al. (32). Insertions were recombined into pADAP by transforming S. entomophila strain A1MO2 (Table 1) with the desired pLAFR3-based construct. After 5 days of growth in nonselective medium, bacteria were selected for resistance to the recombined antibiotic marker and screened for loss of the pLAFR3 tetracycline resistance marker (∼17% of the antibiotic-resistant colonies were tetracycline sensitive). Bioassays and assessment of the maintenance of the plasmid in the bioassayed strain were undertaken, as previously described (23).

DNA isolation and manipulation.

pADAP DNA was isolated from a 50-ml overnight culture of bacteria using a Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) plasmid maxikit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Standard DNA techniques were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (40). Radioactive probes were made using the Megaprime DNA-labeling system (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Southern blot and colony hybridizations were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (40). Visualization of pADAP and its derivatives was done by the method of Kado and Liu (30) as described by Hurst et al. (23). pLAFR3- and pBR322-based plasmids were electroporated into E. coli and S. entomophila strains using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (25 μF; 2.5 kV; 200 Ω) (11).

For DNA sequencing, the previously mapped pADAP subclones (24) were further subcloned or self-ligated. Plasmid templates for DNA sequencing were prepared using High Pure plasmid isolation miniprep kits (Roche Diagnostics GmbH). Sequences were determined on both strands using combinations of subcloned fragments and custom primers. The DNA was sequenced at the University of Waikato DNA Sequencing Facility (http://sequence.bio.waikato.ac.nz) by automated sequencing using an Applied Biosystems 377 autosequencer. The sequences were assembled using SEQMAN (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.). Databases at the National Center for Biotechnology Information were searched using BlastN, BlastX, and BlastP (1). Searches for ORFs were initiated using EDITSEQ (DNASTAR Inc.) and GeneMark (5; http://opal.biology.gatech.edu/GeneMark/). ORFs of unknown function or which show high translated similarity to hypothetical proteins of unknown function are designated Sean, for S. entomophila pADAP; “n” represents the consecutive numbering of that ORF relative to the previously described unidentified ORFs of pADAP under GenBank accession number AF135182. ORFs that have significant translated similarity to proteins with defined functions have been designated with the appropriate nomenclature for their homologues. ORFs thought to be involved in the antifeeding process have been designated afp for antifeeding prophage.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence determined in this study has been deposited in GenBank as an updated version of accession number AF135182; accordingly, the nucleotide numbering described in this paper is relative to the previously described sequence under this accession number.

RESULTS

Three pADAP deletion derivatives were constructed to eliminate the possibility that an ORF yet to be defined encoded within the previously cloned sep-associated region was involved in antifeeding activity. These derivatives had deleted regions within and flanking the sep-associated virulence region (Fig. 1) (22). Bioassays of these pADAP derivatives showed that each deletion variant inhibited the ability of grass grub larvae to feed, indicating that the antifeeding region did not reside within the deleted regions (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Concurrently, peripheral sequencing data of various pADAP subclones had tentatively located the regions of pADAP replication and conjugation, a fimbrial operon, and a region of DNA of unknown translated identity (24). The last region, which encompassed one of the three large HindIII fragments designated pMH52 (Fig. 1), was chosen as a candidate area for the construction of a further pADAP deletion variant called pADS93XbaIΔStuIΔBglIIKn, as outlined in Fig. 2.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of pADAP showing the locations of the restriction enzyme sites for HindIII (outer circle), EcoRI (middle circle), and BamHI (inner circle); the previously identified sep virulence gene (sepA, sepB, and sepC)-associated region (23); and the previously constructed pADAP deletion derivatives, pADK93XbaIΔStuRI, pADK93XbaIΔ14XbaI, and pAD32ΔBglII (Table 1). The peripheral semicircles signify areas of pADAP deleted via the use of the designated flanking restriction enzyme sites (22). Corresponding bioassay results are represented by solid (healthy larvae) and shaded (healthy but nonfeeding larvae) semicircles (Table2). The locations of the XbaI restriction enzyme site and the pUH5.4 (crosshatched HindIII fragment) subclone containing the unique AvrII site used to clone the afp cluster are shown (see the text). Restriction enzymes are abbreviated as follows: A, AvrII; B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; H, HindIII; S, StuI; and X, XbaI.

TABLE 2.

Antifeeding effects of the cloned antifeeding-encoding region (pAF6), its mutated derivatives, pADAP-based subclones, and pADAP deletion derivatives

| Construct | % Feedinga | One tailed t-testb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| df | P | ||

| S. entomophila A1MO2 | 0 | ||

| Control (no bacteria) | 100.0 | ||

| pMH52 | 100.0 | ||

| pMH53 | 100.0 | ||

| pMH54 | 100.0 | ||

| pAD32ΔBglII | 100.0 | ||

| S. entomophila(pAF6) | 0 | ||

| E. coli XL1-Blue(pAF6) | 0 | ||

| pADK93XbaIΔ14XbaI | 100.0 | ||

| pADC20XbaIΔStuI | 100.0 | ||

| pADK93XbaIΔStuI | 100.0 | ||

| pADS93XbaIΔStuIΔBglIIKn | 0 | ||

| Mutated derivatives of pAF6 | |||

| pAF6-1 | 100.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-2 | 0.0 | 1 | NV |

| pAF6-3 | 49.0 | 2 | 0.095 |

| pAF6-4 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-5 | 16.7 | 1 | 0.25 |

| pAF6-6 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-7 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-8 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-9 | 91.7 | 0 | |

| pAF6-10 | 82.5 | 1 | 0.029* |

| pAF6-11 | 72.8 | 2 | 0.017* |

| pAF6-12 | 83.3 | 2 | 0.007** |

| pAF6-13 | 88.9 | 2 | 0.000** |

| pAF6-14 | 100.0 | 1 | NV |

| pAF6-15 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-16 | 100.0 | 1 | NV |

| pAF6-17 | 76.4 | 2 | 0.006** |

| pAF6-18 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-19 | 0.0 | 1 | NV |

| pAF6-20 | 100.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-21 | 0.0 | 1 | NV |

| pAF6-22 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-23 | 85.2 | 3 | 0.003** |

| pAF6-24 | 0.0 | 1 | NV |

| pAF6-25 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| pAF6-26 | 0.0 | 1 | NV |

| pAF6-29 | 0.0 | ||

| pAF6-30 | 4.2 | 1 | 0.20 |

| pAF6-31 | 86.3 | 4 | 0.000** |

| pAF6-32 | 0.0 | 0 | |

Percentage of larvae treated with bacteria feeding on fresh carrot in the period 3 to 6 days after treatment.

One-tailed t test for comparison of feeding by larvae treated with mutant derivatives of pAF6 with feeding by larvae treated with nonmutated pAF6 in the same batch assay. df, degrees of freedom; P, probability of getting the result by chance; *, significance < 0.05; **, significance < 0.01; NV, no variation.

FIG. 2.

Construction of pADAP deletion variant pADS93XbaIΔStuIΔBglIIKn. Shown is a schematic of the previously constructed pADAP deletion variant pADS93XbaIΔStuI with the previously deleted 33.8-kb region (22). The region in the dotted bracket is the 25-kb HindIII fragment in which the 16-kb BglII deletion variant was constructed. To construct a BglII deletion derivative internal to pMH52, the 25-kb HindIII fragment of pMH52 was ligated into the analogous site of pUC19. The resultant construct, pUC52, was restricted with the enzyme BglII and self-ligated (excising 16 kb) to make a vector with a single BglII site, into which the excised BamHI mini-Tn10 kanamycin derivative 103 fragment was inserted, allowing for a selective marker for the recombination of the deletion derivative back into pADAP. The resultant HindIII::mini-Tn10 fragment was then restricted and ligated into the analogous site of pLAFR3. The correct clone was designated pMH52ΔBglII and electroporated into A1MO2(pADS93XbaIΔStuI) for homologous recombination as previously described (see Materials and Methods). Restriction enzymes are abbreviated as follows: B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; H, HindIII; R, EcoRI; S, StuI (only this site is shown); and X, XbaI. Kn indicates the kanamycin antibiotic resistance marker.

In bioassays of the pADS93XbaIΔStuIΔBglIIKn deletion derivative in the S. entomophila strain A1MO2 (Table 1), grass grub larvae continued to feed (Table 2), indicating that a gene(s) implicated in antifeeding activity had been deleted. pADS93XbaIΔStuIΔBglIIKn was shown to be 100% stable over the duration of the bioassay period (data not shown). In conjunction with previous data that showed that the clone pMH52 in a pADAP-cured background (5.6RK) is unable to induce an antifeeding phenotype (22) (Table 2), it was surmised that the regions flanking and including the pMH52 HindIII fragment are needed to induce antifeeding activity. The complete HindIII fragment and regions adjacent to it were sequenced.

Cloning the antifeeding region.

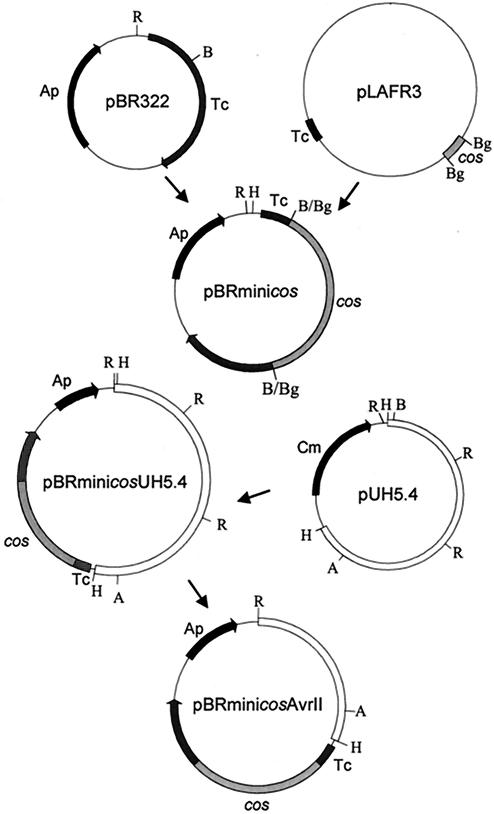

Analysis of sequence data had identified a large area of unknown translated identity flanked by the sep virulence-associated region and a transposon element identified in the previously mapped clone pUH5.4 (24) (Fig. 1). Restriction enzyme analysis of the generated sequence showed that this area could be cloned in its entirety using a XbaI site located in the carboxyl terminus of SepC (which omits the first 736 amino acid residues of the 973-amino-acid SepC protein) and a unique AvrII site located within the pUH5.4 clone (Table 1 and Fig. 1). To clone this region, the vector pBRminicosAvrII was constructed as outlined in Fig. 3. pADAP DNA was purified and restricted with the enzymes AvrII and XbaI, and the resultant 37,733-bp AvrII-XbaI fragment was ligated into the unique AvrII site of pBRminicosAvrII. The resulting ligation was then packaged using a GigapackIIIXL packaging extract (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). One clone (pAF6) was isolated that, based on sequence data, had the expected restriction profile. When bioassayed against the grass grub larvae, the pAF6 construct in the E. coli strain XL1-BlueMRA was found to induce strong antifeeding activity, which often led to a “glassy-opaque” phenotype (Fig. 4D) and in some cases mortality within 14 days. The pAF6 construct was electroporated into the pADAP-cured S. entomophila strain 5.6RK (Table 1); subsequent bioassays of the transformant against grass grub larvae showed results similar to those for the E. coli strain XL1-BlueMRA (Table 2 and Fig. 4E).

FIG. 3.

Construction of pBRminicosAvrII. The 1.6-kb BglII fragment encompassing the cos site of pLAFR3 was excised and ligated into the BamHI site of pBR322 to form pBRminicos. To incorporate the unique AvrII site, the 5.4-kb HindIII fragment from pUH5.4 (Table 1) was ligated into pBRminicos, and the resultant construct was assessed for the correct orientation to allow the later excision of extraneous EcoRI DNA. The correctly oriented construct, called pBRminicosUH5.4, was then digested with EcoRI and self-ligated to produce the construct pBRminicosAvrII containing the unique AvrII site, allowing the insertion of the 37,732-bp AvrII and its XbaI isoschizomer of pADAP to be introduced. Restriction enzymes are abbreviated as follows: A, AvrII; B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII. Antibiotic resistance markers: Ap, ampicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Tc, tetracycline.

FIG. 4.

Photographs taken on day 9 of a standard bioassay. (A) Larvae fed A1MO2(pADAP+) showing distinct amber coloration and absence of feeding, indicated by the unconsumed carrot cube. (B) Healthy feeding larvae. (C) Larvae fed A1MO2(pADK13); the larvae appear healthy but are unable to feed. (D) Larvae fed E. coli(pAF6). (E) Larvae fed 5.6RK(pAF6)(pADAP−) showing nonfeeding, glassy-opaque pathotype and absence of gut clearance, indicated by the red arrows. The red box contains a larva in the later stages of the disease before its eventual death.

Effects of mini-Tn10 insertions on pAF6 disease-causing ability.

To assess which regions of the pAF6 clone were needed to induce a disease phenotype, pAF6 was mutated with the mini-Tn10 transposon derivative 105 (Table 1), and the sites of the insertions were defined by sequence analysis using a mini-Tn10-specific primer (5′ GCTCTCCCCGTGGAGGTAA 3′) (Fig. 5). Each pAF6 mutant in the E. coli strain DHB101 was independently bioassayed against grass grub larvae, and the assays were replicated. The results showed that the disease determinants were confined to a central ∼30-kb region of the pAF6 clone (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Assessment of the stability of pAF6 and its mutated derivatives during the course of the bioassays showed that >97% of the recovered E. coli strains contained the plasmid of interest (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Schematic of the cloned S. entomophila antifeeding gene cluster pAF6. (A) Gene annotation (Table 3), locations of mini-Tn10 insertion points, and results of bioassay (Table 2). The solid circles represent mutations of the pAF6 clone that resulted in an unaltered pathotype (nonfeeding with glassy-opaque appearance); the open circles represent mutations that resulted in the abolition of pathogenicity (P < 0.05). The AvrII and AbaI restriction enzyme sites used to clone the afp cluster are shown. *, peripheral HindIII site from pUH5.4 (see the text). The relative positions of the amb2 locus, phage lysis cassette, and afp cluster are indicated. (B) G+C content of the antifeeding gene cluster (window size, 300; window position shift, 3). The nucleotide numbering is shown below the graph and is relative to the previously annotated sequence listed under accession number AF135182 (dashed line).

Sequence analysis of pAF6.

Putative ORFs and their percent G+C contents, predicted translated similarities, and amino acid sizes are listed in Table 3 and depicted in Fig. 5 and 6. Sequence analysis identified a region between nucleotides (nt) 70274 and 71385 (Fig. 5) with 95% identity to the previously described amb2 locus, which is comprised of two ORFs designated anfA1 and anfA2, speculated to be involved in antifeeding activity against grass grub larvae (38). DNA analysis showed that the translated product of the anfA1 gene contains a NusG-type domain and has similarity to the trans-acting E. coli transcription activator RfaH (2) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

ORFs, G+C contents, and similarities of translated products to protein sequences in current database detected using BlastP

| ORF (amino acids) | Nucleo- tidesa | %G+C | Degree of similarityb | Gene, species (amino acid size) | Accession no. | Degree of similarity to Afp homologuesb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AnfA1 (149) | 70418-70864 | 33.33 | 81/83//154 (1-148) | AnfA1; S. entomophila antifeeding protein (154) | gi|2144163 | |

| 32/51//112 (3-114) | rfaH; Erwinia chrysanthemi transcriptional activator (162) | gi|4163101 | ||||

| “COG0250”; NusG; transcription antiterminator (61.8%; 1-104)c | ||||||

| AnfA2 (96) | 71010-71297 | 39.24 | 51/56//60 (1-58) | AnfA2; S. entomophila antifeeding protein (108) | gi|2144164 | |

| Sea22 (70) | 71571-71780 | 53.33 | No similarity | |||

| Sea23 (43) | 71825-71953 | 50.39 | No similarity | |||

| Enp1 (154) | 72867-73328 | 44.59 | 35/53//145 (9-152) | Rz; Bacteriophage HK620 endopeptidase (155) | gi|13559860 | |

| 29/53//141 (10-150) | Orf37; P. luminescens (149) | gi|27550079 | ||||

| “pfam03245”; bacteriophage lysis protein (92.9%; 9-151)c | ||||||

| Hol1 (68) | 73523-73726 | 42.16 | 38/61//63 (4-66) | ECs1621; E. coli O157:H7 putative holin protein (105) | gi|15830875 | |

| 38/61//60 (1-60) | TchA; P. luminescens (119) | gi|27479676 | ||||

| Mur1 (142) | 74293-74718 | 50 | 61/73//141 (1-141) | ORF3; S. entomophila (144) | gi|10956821 | |

| “COG3772”; Phage-related lysozyme (muraminidase) (95.4%; 1-141)c | ||||||

| Afp1 (150) | 74895-75344 | 50 | 73/89//149 (1-149) | Plu1730; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (149) | gi|37525667 | Afp5 22/41//137 (13-139) |

| Afp2 (355) | 75363-76427 | 56.15 | 48/64//362 (1-354) | Plu1688; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (360) | gi|37525626 | Afp3 35/48/452 (1-354) |

| “COG3497”; phage tail sheath protein FI (41.6%; 184-350)c | Afp4 40/60//167 (189-352) | |||||

| “pfam04984”; phage tail sheath protein (53.2%; 121-350)c | ||||||

| Afp3 (451) | 76447-77802 | 57.74 | 46/64//466 (1-451) | Plu1728; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (466) | gi|37525665 | Afp2 35/48/452 (1-451) |

| “COG3497”; phage tail sheath protein FI (43.4%; 276-449)c | Afp4 37/59//170 (284-449) | |||||

| “pfam04984”; phage tail sheath protein (39%; 276-447)c | ||||||

| Afp4 (417) | 77842-79095 | 59.33 | 43/57//413 (1-408) | Plu2528; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (398) | gi|37526420 | Afp2 40/60//167 (238-404) |

| “COG3497”; phage tail sheath protein FI (40.4%; 232-296)c | Afp3 37/59//170 (236-404) | |||||

| “pfam04984”; phage tail sheath protein (87.2%; 34-396)c | ||||||

| Afp5 (151) | 79095-79544 | 58 | 72/83//148 (1-148) | Plu1704; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (152) | gi|37525642 | Afp1 22/41//137 (5-138) |

| Afp6 (55) | 79541-79708 | 57.14 | 50/64//53 (1-53) | Plu2526; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (59) | gi|37526418 | |

| Afp7 (229) | 79705-80394 | 57.25 | 57/70//223 (1-223) | Plu2391; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (227) | gi|37526292 | |

| Afp8 (530) | 80391-81980 | 57.8 | 36/56//532 (4-529) | Plu2392; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (534) | gi|37526293 | |

| 25/43//434 | Mdeg3433 Microbulbifer degradans 2-40 (570) | |||||

| “COG3500”; Phage protein D (82.6%; 45-337)c | gi|23029699 | |||||

| “COG3501”; VgrG; uncharacterized protein conserved in bacteria (87.8%; 3-469)c | ||||||

| “pfam04524”; DUF586; protein of unknown function (96.2%; 357-426)c related to the phage-related baseplate assembly protein V | ||||||

| Afp9 (140) | 82001-82423 | 56.26 | 48/68//135 (1-135) | Plu2393; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (140) | gi|37526294 | |

| “COG3628”; phage baseplate assembly protein W (74.1%; 14-99)c | ||||||

| “pfam04965”; GPW/gp25 family (72.1%; 33-102)c | ||||||

| Afp10 (141) | 82420-82842 | 57.68 | 40/50//140 (1-140) | Plu1658; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (138) | gi|37525599 | |

| Afp11 (607) | 82919-84742 | 60.03 | 41/57//397 (209-599) | Plu1698; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (900) | gi|37525636 | |

| 32/47//268 (6-268) | ||||||

| Afp12 (964) | 84735-87626 | 58.02 | 46/62//974 (1-957) | Plu1678; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (959) | gi|37525616 | |

| Afp13 (490) | 87652-89123 | 53.63 | 32/46//240 (38-273) | Plu1718; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (434) | gi|37525655 | |

| 58/74//43 (336-378) | ||||||

| 41/63//55 (330-384) | ||||||

| 48/75//49 (331-337) | ||||||

| 24/43//120 (258-377) | Hypothetical 87.1 K protein; bovine adenovirus 3 (833) | gi|420505 | ||||

| 30/62//50 (330-379) | ||||||

| 37/60//40 (334-373) | ||||||

| 37/58//43 (331-373) | Z86065.1:132..2066; duck adenovirus 1 fiber (644) | gi|2052001 | ||||

| Afp14 (555) | 89121-90788 | 53.69 | 25/38//609 (4-547) | Plu1717; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (551) | gi|37525654 | |

| Afp15 (697) | 90825-92915 | 51.84 | 51/67//681 (22-696) | plu1716; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (694) | gi|37525653 | |

| “COG0464”; ATPases of the AAA+ class (97.8%; 491-686)c | ||||||

| “pfam00004”, AAA, ATPase, (97.8%; 491-697)c | ||||||

| Afp16 (296) | 92986-93873 | 52.93 | 48/65/287 (9-295) | Plu2516; P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (298) | gi|37526408 | |

| Afp17 (359) | 93979-95055 | 47.45 | No similarity | |||

| Afp18 (2367) | 95257-102357 | 44.4 | No similarity | |||

| Int1 (203) | 102492-103103 | 50 | 68/81//202 (1-201) | IS3 A. tumefaciens C58; transposase (512) | gi|17743800 | |

| 54/65//202 (1-201) | OrfB putative transposase; Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 (210)a | gi|8885849 | ||||

| “pfam00665”; rve integrase core domain (100%; 36-197)c | ||||||

| “COG2801”; Tra5; transposase (77.2%; 1-197)c | ||||||

| Sea24 (340) | 103246-104268 | 53.86 | 55/73//290 (1-288) | Riorf46; A. rhizogenes pRi1724; probable transposase gene (475) | gi|10954692 | |

| “pfam00665”; rve integrase core domain (90.6%; 23-178)c | ||||||

| Sea25 (82) | 104359-104604 | 52.85 | 35/60//65 (3-67) | PA2221; conserved hypothetical protein; P. aeruginosa PA01 (401) | gi|15597417 | |

| 37/57//66 (2-67) | Riorf46; A. rhizogenes pRi1724; probable transposase gene (475) | gi|10954692 | ||||

| Sea26 (118) | 104784-105140 | 53.22 | 46/65//66 (1-66) | R0148; Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi pR27; putative transposase (468) | gi|10957337 | |

| 40/66//66 (1-66) | Riorf46; A. rhizogenes pRi1724; probable transposase gene (475) | gi|10954692 | ||||

| Sea27 (325) | 105158-106132 | 52.41 | 57/71//301 (2-300) | Yi12; unknown Rhizobium etli (473) | gi|21492773 | |

| “pfam00665”; rve integrase core domain (90.6%; 135-290)c |

Nucleotide sequence is a continuum from the previously published sequence GenBank AF135182.

Amino acid similarity (percent identity/percent similarity over amino acid residue) in relation to sequence generated in this study.

Percent identity to the protein domain indicated by quotation marks relative to the deduced gene products of the sequenced ORF.

FIG. 6.

Predicted genetic organizations of the S. entomophila afp gene cluster and its P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 analogues (12). The diagram is to scale and is positioned relative to the ORF afp1. ORFs are represented by arrows, with their designations below; the boxes represent remnant elements. Areas of significant protein similarity are depicted by similar shading patterns. The arrows with diagonal lines represent proteins containing a repeat motif; the checkered elements signify similarity to transposon-type elements. Solid stars indicate ORFs in which the translated product has similarity to the cited virulence factor. Open stars indicate tentative virulence factors with no homologues with functional identity in the current databases (see the text). Similarities to protein domains are listed above the afp gene cluster (Table 3). The number at the end of each schematic indicates the nucleotide number of the afp cluster (GenBank accession no. 38176651) or in P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (GenBank accession no. 37524032).

Situated 1,570 to 3,421 bp downstream of the amb2 locus is an intact lysis cassette consisting of three ORFs, designated enp1, hol1, and mur1 (Fig. 5 and Table 3), that encode an endopeptidase, a holin, and a lysozyme, respectively and that are typically associated with double-stranded-DNA phages (53). The ORF enp1 encodes a potential Rz-type endopeptidase identified in lambdoid-type phages (52). Analysis of the hydropathy profile of Enp1 showed a significantly hydrophobic amino terminus capable of spanning the lipid bilayer (data not shown). The translated product of the ORF hol1 is a putative bacteriophage holin (Table 3). The holin provides the rate-determining step in the lysis of the bacterial cell, as it permits access of the endolysin to the peptidoglycan-murein layer by forming stable, nonspecific pores in the membrane. Holins usually encode a dual start motif, enabling the transcription of a truncated analogue called an anti-holin-holin inhibitor, which allows fine tuning of the lytic schedule (48, 52). No dual start motif was identified, suggesting that lysis is confluent with gene expression. The ORF mur1, encoding a potential muramidase-type lysozyme enzyme, is 567 bp downstream of hol1. mur1 has no DNA similarity but has significant translated similarity to the previously described ORF3, located upstream of the sep virulence-associated region (Table 3) (23).

Initiating 177 bp downstream of mur1 are 16 ORFs, the translated products of which show significant similarity to the products of six putative remnant prophage gene clusters identified in the recently sequenced genome of Photorhabdus luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (12) (Table 3 and Fig. 6). Similarity was also scored to two remnant prophages in the “necrotizing factor-like pnf” gene cluster, part of a putative pathogencity island identified by Waterfield et al. (50) in the P. luminescens strain W14. A comparison of the genes identified in the pAF6 clone with genes identified in putative P. luminescens prophage clusters shows high conservation in both amino acid sequence length and gene order (Fig. 6). The translated products of a number of the ORFs contain virus-associated domains (Table 3 and Fig. 6). Together, these data suggest that these ORFs may form part of a novel defective prophage, and they have accordingly been designated afp for antifeeding prophage.

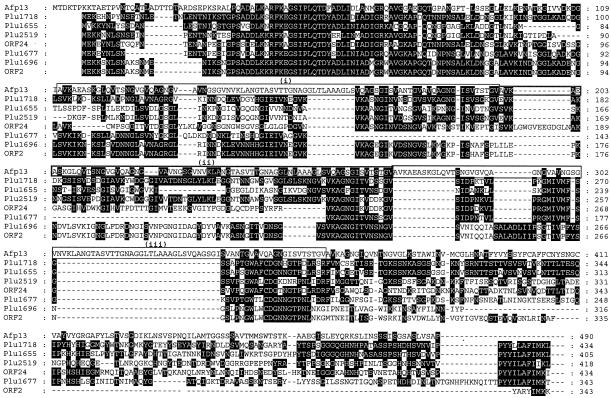

Though the translated products of the ORFs afp1 and afp5 exhibit high similarity to each other, the degrees of similarity to their respective P. luminescens homologues are higher in both amino acid sequence and length. The conservation of amino acid length is striking: Afp5 and its homologues are 152 amino acids long, and the 147-amino-acid Afp1 is not too different from its P. luminescens homologues, which are all 149 amino acid residues long. Between afp1 and afp5 are afp2 to afp4, the translated products of which have high similarity to the tail sheath domains derived from the Gp18 protein of bacteriophage T4 (pfam04984) and F1 of bacteriophage P2 (COG3497) (Table 3). The relative sizes of afp2, afp3, afp4, and their P. luminescens homologues are comparable: the smallest ORF, afp3 (1,355 bp), is behind the largest, afp2 (1,064 bp), while the third ORF, afp4, is intermediate in size (1,253 bp) (Table 3 and Fig. 7). The third tail sheath fiber-type protein of Afp4 and its P. luminescens homologues contain a less similar amino terminus and carboxyl terminus compared to Afp2, Afp3, and their homologues (Fig. 7). The pAF6-35 mutation in afp2 results in abolition of the disease process, showing that this tentative tail sheath fiber protein is essential to the disease process (Fig. 5 and Table 3).

FIG. 7.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of Afp2, Afp3, Afp4, and P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 homologues. Identical amino acid residues are shaded.

Aside from protein similarity to various components of the P. luminescens remnant prophage homologues (Table 3), the predicted translated products of afp6, afp7, afp10, afp11, afp12, afp14, and afp16 contain no significant identity to proteins in the current databases. Though Afp11 and its homologues show significant amino and carboxy terminus similarity, the intervening regions and the sizes of Afp11 (587 amino acid residues) and Plu2395 (1,341 amino acid residues) differ from those of the remaining P. luminescens homologues, which range in size from 879 to 888 amino acids (Fig. 6). The translated product of plu2396, located adjacent to Plu2395, is also atypically large relative to its homologues (Fig. 6). Results from mini-Tn10 mutagenesis showed that mutations in afp7, afp14, or afp16 had no effect on the disease process (Fig. 5 and Table 2).

The predicted protein product of afp8 and its homologues contains the Rhs-E-G Rhs-associated VgrG protein domain (COG3501), a domain of unknown function present in many bacteria, and also shows 82.6% similarity to the phage D domain (COG3500) (Table 3). Afp9 contains 74.1% similarity to the phage baseplate assembly protein W domain (COG3628) (Table 3) derived from bacteriophage T4—a structural component of the outer wedge of the Gp25 phage baseplate (16). The translated product of ORF afp13 contains three large repeats in both its DNA and amino acid sequences, with two large 88-amino-acid-residue repeats flanking a smaller repeat (Fig. 8). The carboxyl terminus of Afp13 shows slight similarity to internal regions of the bovine adenovirus B fiber protein and the duck adenovirus 1 (Table 3). The only other member of the afp cluster in which the translated product contains a domain is the carboxy terminus of Afp15 and its homologues that contain an ATPase+++ domain (Fig. 9 and Table 3). Accordingly, Afp15 and its P. luminescens homologues contain the Walker A (Afp15; amino acid residues 494 to 501) and Walker B (Afp15; amino acid residues 616 to 619) boxes (Fig. 9). The region flanking and including the Walker A and B domains of afp15 (pADAP; nt 92358 to 92717) is highly conserved, exhibiting >80% similarity to the DNAs of its P. luminescens counterparts. The pAF6-1 mutation located in the region between the Walker A and Walker B boxes (pADAP; nt 92640) (Fig. 9) results in the abolition of the antifeeding process (Table 2), showing that the ATPase+++ domain is essential to the disease process. Conversely, the pAF6-11 mutation residing 202 bp upstream from the afp15 amino terminus had no effect on the disease process (Fig. 5 and Table 2) and hence may not interfere with the mature Afp15 protein.

FIG. 8.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of Afp13 and P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 and W14 homologues. Three large repeat sequences (labeled i to iii) were detected within the Afp13 amino acid sequence. Repeats i and iii are 88 amino acid residues long (boxed) compared to the smaller 73-amino-acid degenerate repeat (ii; boldface box). Identical amino acid residues are shaded.

FIG. 9.

Alignment of the carboxyl-terminal amino acid sequences of Afp15 and P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 homologues showing the locations of the tentative Walker A (GX4GKT) and Walker B (YHyDE) domains, where X is any amino acid and Hy is a hydrophobic amino acid. The solid triangle indicates the location of the pAF6-1 mutation. Identical amino acid residues are shaded.

Amino acid comparisons of the afp gene cluster with the various P. luminescens prophage clusters typically show that the translated products of one of the two ORFs downstream of Afp16 and its homologues either has similarity to a toxin, such as the P. luminescens mcf cytotoxin and RTX-dermonecrotic toxin, or no functional homologues at all (Fig. 6). The translated product of afp18 is large (2,367 amino acid residues), and six mutations within the afp18 ORF were found to abolish antifeeding activity. However, the pAF6-2 mutation located 134 amino acid residues from the carboxyl terminus of Afp18 has no effect on the disease process (Fig. 5 and Table 2).

Located 135 bp downstream of afp18 and in the same orientation as the afp cluster is the ORF int1, the translated product of which has high similarity to an IS3-type transposase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58. However, relative to size, Int1 more closely resembles the putative transposase encoded by OrfB of Pseudomonas sp. strain JR1 (Table 3). The Int1 protein contains an rve integrase core domain (pfam00665) (Table 3), an endonuclease that catalyzes the DNA strand transfer reaction of the 3′ ends of the viral DNA to the 5′ ends of the integration site. Transcribed in the opposite direction to the afp gene cluster and int1 are two regions (pADAP; nt 103157 to 104381 and 104695 to 105909) of DNA exhibiting 94% similarity to each other that encode intermittent BlastX similarity to the probable transposase Riorf46 from A. rhizogenes (Table 3). Though four potential ORFs (sea24 to sea27) containing potential ribosomal binding sites were detected within these regions (Table 3), the intermittent BlastX similarity to the Riorf46 transposases suggests they may be speculative.

Analysis of the G+C content of the pAF6 clone (Fig. 5 and Table 3) revealed that the ORFs afp17 and afp18 and the genes comprising a tentative lysis cassette (enp1, hol1, and mur1) have significantly greater A-T content than the afp cluster.

DISCUSSION

We have defined a 30-kb region of pADAP encoding a potential prophage necessary for antifeeding activity toward larvae of C. zealandica. The pAF6 clone was able to induce antifeeding activity against grass grub larvae in an E. coli or S. entomophila pADAP plasmid-cured strain, causing rapid cessation of feeding followed by onset of a glassy-opaque phenotype. The disease phenotype differed from that of the wild-type amber disease, as gut clearance was incomplete, with the larvae retaining a darkened midgut (Fig. 4D and E). The antifeeding-associated clone pAF6 caused not only antifeeding activity but also death of the larvae within 2 weeks of infection. This contrasts with the prolonged nonfeeding period prior to the death of pADAP-treated larvae and is possibly the result of a copy number difference between the pBR322-based clone pAF6 (∼50 per chromosome equivalent) and pADAP (estimated at 1 copy per chromosome equivalent). The apparent increased lethality of the pBR322-based antifeeding clone raises the question of why the natural system has not evolved to be up-regulated to increase the speed of kill in the grass grub. The grass grub-amber disease relationship is typified by cycles of grass grub buildup and decline associated with delayed density dependence of the disease (26). It is plausible that disease-causing properties of S. entomophila are down-regulated to prolong the chronic infection and maintain the survival of S. entomophila in the field. Alternatively, the antifeeding effect, which shuts down movement of food through the insect gut, allows time for the Sep proteins and/or bacteria to accumulate and interact with their target site, resulting in amber disease. Construction of a pADAP-based afp mutant would allow further study of the amber disease process. The mechanism behind the less stable antifeeding effect exerted by the virulence clone (pBM32), containing only the sepA, sepB, and sepC virulence determinants, remains unknown, but it may be a host response to the disease process as a whole.

DNA sequence analysis of the pAF6 clone revealed a region of high DNA sequence similarity and, accordingly, translated protein similarity to the gene products of the previously documented amb2 locus (39) (Table 3), a locus speculated to encode antifeeding activity against C. zealandica. Results from the present study and a previous study (22) indicated that the amb2 locus is not directly involved in the antifeeding process. Instead, the high similarity of the AnfA1 protein to RfaH, a member of the NusG-type activator family, signifies a different role. The RfaH protein is required for the transcription of genes encoding synthesis of the sex pilus and lipopolysaccharide core attachment of the O antigens of E. coli and Salmonella and hemolysin synthesis in E. coli. RfaH-like NusG is believed to work by enhancing the transcriptional elongation of RNA to proximal genes in an operon by smoothing out hairpin structures in the RNA (3); hence, the AnfA1 protein may play a similar role. Bioassays of the pAF6-19 mutation, which inactivates the AnfA1 locus (Fig. 5 and Table 3), showed no effect on the inhibition of antifeeding activity. It is plausible that the increased copy number of the pBR322-based pAF6 construct relative to pADAP may enable higher levels of mRNA to be produced, nullifying the percentage of preterminated transcripts as a whole. Upstream of the amb2 locus (pADAP; nt 70019 to 70276) is a significantly A+T-rich region (81.4%) containing several degenerate repeats and an inverted repeat (data not shown). This typifies DNA associated with gene regulation and may be the site where factors that interact with the amb2 locus and indirectly with the afp operon interact.

The presence of a complete lysis gene cluster upstream of the antifeeding gene operon raises questions regarding the timing of the disease process. It is known that the induction of antifeeding activity occurs 1 to 3 days before the onset of the sep-associated amber disease. The sep-associated region contains a single lysis gene (orf3) previously thought to be implicated in the release of the sep virulence-associated proteins (22). The presence of an intact lysis cassette suggests that when the pathogenicity process is triggered, the bacterial cell undergoes lysis, resulting in the death of a subset of the bacterial population. A similar scenario has been indirectly postulated for the release of large proteins from X. nematophilus (9) and P. luminescens (49). If true, this would explain the inability to detect SepA-, SepB-, or SepC-green fluorescent protein translational fusions (M. R. H. Hurst, unpublished data) and failure to define a site of colonization by S. entomophila during the disease process using either flourescein isothiocyanate-labeled bacteria or S. entomophila encoding constitutive green fluorescent protein (21, 29). It would also require that a subset of the infective bacterial population remain uninduced, enabling the bacteria to survive the lysis process and colonize the grass grub intestinal tract.

Mutagenesis and sequence analysis identified 18 genes essential for the cessation of feeding in C. zealandica larvae. Homologues of 16 of these genes reside as predicted prophage remnants in the P. luminescens strains TTO1 and W14. The translated products of the three ORFs afp2 to -4 showed high similarity to the tail sheath protein domains of the bacteriophages T4 and P2 (Table 3), and the proteins Afp8 and Afp9 showed similarity to the phage baseplate-related proteins (Table 3). This suggests that afp and its P. luminescens homologues may physically resemble the phage tail-like bacteriocins, such as enterocoliticin of Y. enterocolitica (44) or xenorhabdicin from X. nematophilus (46), which are able to kill an array of bacterial species.

The predicted protein Afp13 contains three conserved amino acid repeats that are shared to some extent by its P. luminescens homologues. Protein repeat motifs have been identified in many virulence-related proteins of gram-positive bacteria, where they have been found to function as ligands to various host receptors or to have specific affinity for cellular components (36, 41). Although the role of the Afp13 repeat structure has yet to be elucidated, it is not believed to be a virulence factor by itself. The repeat motif may instead be implicated in the binding of the downstream proteins to the defective prophage tail-like structure.

Many bacteriophage-based virulence factors have been described, such as the pore-forming toxin CTX of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (18), the Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin, the diphtheria toxin of Corynebacterium diphtheriae (4), the cholera toxin of Vibrio cholerae (31), and the Shiga-like toxins and enterohemolysin produced by E. coli (6, 38). The location of potential P. luminescens toxin genes at the 3′ end of each prophage cluster is relative to the position of the afp17 and -18 genes (Fig. 6). Hence, the ORFs afp17 and afp18 may encode the active factor(s) responsible for antifeeding activity toward grass grub larvae. Further evidence for this comes from the difference between the G+C contents of afp17 and afp18 and those of the other afp genes (Fig. 5B), indicative of genes acquired by horizontal gene transfer, a mechanism thought to be responsible for the acquisition of the DNA encoding the cytotoxin gene for the pore-forming toxin of the phage phi-CTX of P. aeruginosa, which resides within a region of atypical nucleotide content (35).

Typically, viruses of gram-negative bacteria have highly mosaic structures, with many viruses encoding the same genes but at different locations in their genomes (10). The high amino acid similarity, amino acid length, and the conserved nature of this organizational pattern of the afp cluster and its P. luminescens counterparts suggest that these remnant prophages may represent a novel toxin delivery system that utilizes a phage-type structure through which to mediate transfer of the toxins located at the 3′ end of each prophage remnant. The ability to mediate such a transfer may be provided by Afp15 and its P. luminescens homologues that contain an ATPase+++ domain (Table 3) previously implicated in providing a chaperon function assisting in the assembly or disassembly of protein complexes (37).

To our knowledge, this is the first example of a phage-type element located on a mobile plasmid. The absence of a phage replication region and ORFs encoding packaging functions points to the independent acquisition of the afp phage-type cluster and indicates that pADAP is providing the replicative function. An intact integrase gene (int1) located at the 3′ end of the afp cassette indicates that the prophage may be able to mediate its excision and/or integration. The absence of a virus-type lysis cassette associated with the P. luminescens prophages suggests that the afp lysis cassette has been recently acquired by pADAP, as is evident from the relative differences between the G+C contents of the lysis cassette and the afp gene cluster (Fig. 5). This may represent an evolutionary step in the emergence of a new virus and raises questions as to the origins of the defective prophage itself. The presence of viral domains similar to those described in mammalian and avian adenoviruses suggests a possible eukaryotic target, and hence, the phage may be able to infect insect cell lines. In order to gain greater understanding of the disease process, attempts will be made to induce and purify the prophage, assess its structure by electron microscopy, and express the ORFs afp17 and afp18 in artificial expression vectors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a contract from the New Zealand Foundation for Research, Science and Technology.

We thank Richard Townsend for the provision of grass grub larvae and Maureen O'Callaghan for proofreading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey, M. J., V. Koronakis, T. Schmoll, and C. Hughes. 1992. Escherichia coli HlyT protein, a transcriptional activator of haemolysin synthesis and secretion, is encoded by the rfaH (sfrB) locus required for expression of sex factor and lipopolysaccharide genes. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1003-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey, M. J., C. Hughes, and V. Koronakis. 1997. RfaH and the ops element, components of a novel system controlling bacterial transcription elongation. Mol. Microbiol. 26:845-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barksdale, L., and S. B. Arden. 1974. Persisting bacteriophage infections, lysogeny, and phage conversions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 28:265-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besemer, J., and M. Borodovsky. 1999. Heuristic approach to deriving models for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3911-3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beutin, L., U. H. Stroeher, and P. A. Manning. 1993. Isolation of enterohemolysin (Ehly2)-associated sequences encoded on temperate phages of Escherichia coli. Gene 132:95-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolivar, F., R. L. Rodriguez, P. J. Greene, M. C. Betlach, H. L. Heyneker, and H. W. Boyer. 1977. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene 2:95-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen, D., T. A. Rocheleau, M. Blackburn, O. Andreev, E. Golubeva, R. Bhartia, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 1998. Insecticidal toxins from the bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Science 280:2129-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brillard, J., M. H. Boyer-Giglio, N. Boemare, and A. Givaudan. 2003. Holin locus characterisation from lysogenic Xenorhabdus nematophila and its involvement in Escherichia coli SheA haemolytic phenotype. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 218:107-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casjens, S. 2003. Prophages and bacterial genomics: what have we learned so far? Mol. Microbiol. 49:277-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dower, W. J., J. F. Miller, and C. W. Ragsdale. 1988. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:6127-6145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duchaud, E., C. Rusniok, L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, A. Givaudan, S. Taourit, S. Bocs, C. Boursaux-Eude, M. Chandler, J. F. Charles, E. Dassa, R. Derose, S. Derzelle, G. Freyssinet, S. Gaudriault, C. Medigue, A. Lanois, K. Powell, P. Siguier, R. Vincent, V. Wingate, M. Zouine, P. Glaser, N. Boemare, A. Danchin, and F. Kunst. 2003. The genome sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Nat. Biotechnol. 21:1307-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glare, T. R., G. E. Corbett, and A. J. Sadler. 1993. Association of a large plasmid with amber disease of the New Zealand grass grub, Costelytra zealandica, caused by Serratia entomophila and Serratia proteamaculans. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 62:165-170. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimont, P. A. D., T. A. Jackson, E. Ageron, and M. J. Noonan. 1988. Serratia entomophila sp. nov. associated with amber disease in the New Zealand grass grub, Costelytra zealandica. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 38:1-6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grkovic, S., T. R. Glare, T. A. Jackson, and G. E. Corbett. 1996. Genes essential for amber disease in grass grub are located on the large plasmid found in Serratia entomophila and Serratia proteamaculans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2218-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruidl, M. E., N. C. Canan, and G. Mosig. 1994. Bacteriophage T4 gene 25. Mol. Microbiol. 12:343-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gulig, P. A., H. Danbara, D. G. Guiney, A. J. Lax, F. Norel, and M. Rhen. 1993. Molecular analysis of spv virulence genes of the Salmonella virulence plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 7:825-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi, T., H. Matsumoto, M. Ohnishi, and Y. Terawaki. 1993. Molecular analysis of a cytotoxin-converting phage, phi CTX, of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: structure of the attP-cos-ctx region and integration into the serine tRNA gene. Mol. Microbiol. 7:657-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofte, H., and H. R. Whiteley. 1989. Insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol. Rev. 53:242-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu, P., J. Elliott, P. McCready, E. Skowronski, J. Garnes, A. Kobayashi, R. R. Brubaker, and E. Garcia. 1998. Structural organization of virulence-associated plasmids of Yersinia pestis. J. Bacteriol. 180:5192-5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurst, M. R., and T. A. Jackson. 2002. Use of the green fluorescent protein to monitor the fate of Serratia entomophila causing amber disease in the New Zealand grass grub, Costelytra zealandica. J. Microbiol. Methods 50:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurst, M. R. H. 1999. Investigation into the plasmid-borne pathogenicity determinants of amber disease from the Enterobacterium Serratia entomophila. Ph.D. thesis. University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

- 23.Hurst, M. R. H., T. R. Glare, T. A. Jackson, and C. W. Ronson. 2000. Plasmid-located pathogenicity determinants of Serratia entomophila, the causal agent of amber disease of grass grub, show similarity to the insecticidal toxins of Photorhabdus luminescens. J. Bacteriol. 182:5127-5138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurst, M. R. H., and T. Glare. 2002. Restriction map of the Serratia entomophila plasmid pADAP carrying virulence factors for Costelytra zealandica. Plasmid 47:51-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson, T. A., J. F. Pearson, M. O'Callaghan, H. K. Mahanty, and M. Willocks. 1992. Pathogen to product—development of Serratia entomophila Enterobacteriaceae as a commercial biological control agent for the New Zealand grass grub Costelytra zealandica, p. 191-198. In T. A. Jackson and T. R. Glare (ed.), Use of pathogens in scarab pest management. Intercept Ltd., Andover, United Kingdom.

- 26.Jackson, T. A. 1993. Advances in the microbial control of pasture pests in New Zealand, p. 304-311. In R. A. Prestidge (ed.), Proceedings of the 6th Australasian Conference on Grassland Invertebrate Ecology. AgResearch, Hamilton, New Zealand.

- 27.Jackson, T. A., A. M. Huger, and T. R. Glare. 1993. Pathology of amber disease in the New Zealand grass grub, Costelytra zealandica Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 61:123-130. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson, T. A. 1995. Amber disease reduces trypsin activity in midgut of Costelytra zealandica Coleoptera; Scarabaeidae larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 65:68-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson, T. A., D. G. Boucias, and J. O. Thaler. 2001. Pathobiology of amber disease, caused by Serratia spp., in the New Zealand grass grub, Costelytra zealandica. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 4:232-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kado, C. I., and S. T. Liu. 1981. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 145:1365-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karaolis, D. K., S. Somara, D. R. Maneval, Jr., J. A. Johnson, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. A bacteriophage encoding a pathogenicity island, a type-IV pilus and a phage receptor in cholera bacteria. Nature 399:375-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleckner, N., J. Bender, and S. Gottesman. 1991. Uses of transposons with emphasis on Tn10. Methods Enzymol. 204:139-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorow, D., and J. Jessee. 1990. Max efficiency DH10Btm: a host for cloning methylated DNA. Focus 12:19. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan, J. A., M. Sergeant, D. Ellis, M. Ousley, and P. Jarrett. 2001. Sequence analysis of insecticidal genes from Xenorhabdus nematophilus PMFI296. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2062-2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakayama, K., S. Kanaya, M. Ohnishi, Y. Terawaki, and T. Hayashi. 1999. The complete nucleotide sequence of phi CTX, a cytotoxin-converting phage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for phage evolution and horizontal gene transfer via bacteriophages. Mol. Microbiol. 31:399-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navarre, W., and W. O. Schneewind. 1999. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:174-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neuwald, A. F., L. Aravind, J. L. Spouge, and E. V. Koonin. 1999. AAA+: a class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 9:27-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newland, J. W., N. A. Strockbine, S. F. Miller, A. D. O'Brien, and R. K. Holmes. 1985. Cloning of Shiga-like toxin structural genes from a toxin converting phage of Escherichia coli. Science 230:179-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nunez-Valdez, M. E., and H. K. Mahanty. 1996. The amb2 locus from Serratia entomophila confers anti-feeding effect on larvae of Costelytra zealandica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Gene 172:75-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Shimoji, Y., Y. M. Ogawa, H. Osaki, S. Kabeya, S. Maruyama, T. Mikami, and T. Sekizaki. 2003. Adhesive surface proteins of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae bind to polystyrene, fibronectin, and type I and IV collagens. J. Bacteriol. 185:2739-2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silhavy, T. J., M. L. Berman, and L. W. Enquist. 1984. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 43.Staskawicz, B., D. Dahlbeck, N. Keen, and C. Napoli. 1987. Molecular characterization of cloned avirulence genes from Race 0 and Race 1 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J. Bacteriol. 169:5789-5794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strauch, E., H. C. Kaspar, C. Schaudinn, P. Dersch, K. Madela, C. Gewinner, S. Hertwig, J. Wecke, and B. Appel. 2001. Characterization of enterocoliticin, a phage tail-like bacteriocin, and its effect on pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5634-5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeshita, S., M. Sato, M. Toba, W. Masahashi, and T. Hashimoto-Gotoh. 1987. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ alpha-complementation and chloramphenicol or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene 61:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thaler, J. O., S. Baghdiguian, and N. Boemare. 1995. Purification and characterization of xenorhabdicin, a phage tail-like bacteriocin, from the lysogenic strain F1 of Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2049-2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trought, T. E. T., T. A. Jackson, and R. A. French. 1982. Incidence and transmission of a disease of grass grub Costelytra zealandica in Canterbury. N. Z. J. Exp. Agric. 10:79-82. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, I. N., D. L. Smith, and R. Young. 2000. Holins: the protein clocks of bacteriophage infections. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:799-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waterfield, N. R., D. J. Bowen, J. D. Fetherston, R. D. Perry, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 2001. The tc genes of Photorhabdus: a growing family. Trends Microbiol. 9:185-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waterfield, N. R., P. J. Daborn, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 2003. Genomic islands in Photorhabdus. Trends Microbiol. 10:541-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young, R. 1992. Bacteriophage lysis: mechanism and regulation. Microbiol. Rev. 56:430-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young, R., I. Wang, and W. D. Roof. 2000. Phages will out: strategies of host cell lysis. Trends Microbiol. 8:120-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]