Abstract

FRET has been widely used as a spectroscopic tool in vitro to study the interactions between transmembrane helices in detergent and lipid environments. This technique has been instrumental to many studies that have greatly contributed to quantitative understanding of the physical principles that govern helix-helix interaction in the membrane. These studies have also improved our understanding of the biological role of oligomerization in membrane proteins. In this review, we focus on the combinations of fluorophores used, the membrane mimetic environments and measurement techniques that have been applied to study model systems as well as biological oligomeric complexes in vitro. We highlight the different formalisms used to calculate FRET efficiency, and the challenges associated with accurate quantification. The goal is to provide the reader with a comparative summary of the relevant literature for planning and designing FRET experiments aimed at measuring transmembrane helix-helix association.

Introduction

Integral membrane proteins are extremely important biologically. They comprise a quarter to a third of all proteomes1, perform multiple important biological functions such as signaling, material transport and defense. They are also the target for more than half of the currently marketed drugs2.

Structurally, there are two main classes of integral membrane proteins, the helical and the barrel proteins3. The more common helical class spans the lipid bilayer with transmembrane (TM) helices that typically comprise 20–30 hydrophobic amino acids. The helical membrane proteins are either designated as bitopic, which have a single TM helix, or as polytopic, which have multiple TM helices folded into a bundle. The transmembrane beta barrel occur in the outer membrane of bacteria and organelles of endosymbiotic origin, mitochondria and chloroplasts. Beta barrels often form channels and pores, with hydrophobic residues pointing toward the lipid region and more polar residues toward the hydrated pore of the barrel.

Structural information serves as a nucleation point to understand the functional mechanism of any macromolecular system, but because membrane proteins are embedded in a chemically heterogeneous lipid bilayer, their biophysical characterization can be very challenging. The structural investigation of membrane proteins is becoming more feasible due to developments in the overexpression of proteins, their solublization, and ways of increasing protein stability4,5. Nevertheless, the rate at which the structure of membrane proteins is solved still lags behind that of soluble proteins6.

Along with structural studies, research has focused on understanding oligomerization, which is increasingly seen as a common occurrence in the case of membrane proteins7. An important foundation for these studies has been laid two decades ago by the Two-Stage Model8, which frames the membrane protein folding problem into two thermodynamically independent stages: 1) the insertion of individual transmembrane helices into the bilayer to form stable independent helices; and 2) the association between these individual helices to form the final folded tertiary structure or to form quaternary oligomeric complexes.

This model suggests that in the case of membrane proteins, both the folding and the oligomerization processes share a common central event – the lateral association of individual TM domains. Thus, study of the oligomerization of these helices is a way to understand the folding principles of membrane proteins. Even though the Two-Stage Model may be oversimplified and not take into account the complexity of biological insertion and potential transitional states during insertion or post-insertion, much of the existing structural and functional data provide general support for its basic thermodynamic assumptions9. With this basis, the study of TM helix oligomerization has contributed to significant progress in understanding the principles and motifs involved in folding in the membrane10.

Methods for studying helix-helix association: biophysical methods in vitro

A number of biophysical methods have significantly contributed to understanding the energetics of TM helix oligomerization, such as Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)11–15, sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation (SE-AUC)16,17, SDS-PAGE18,19, disulfide exchange equilibrium20,21 and steric trapping22,23. Among these methods, the two most widely used are SE-AUC and FRET. SE-AUC is directly sensitive to the oligomeric mass of an associated complex and is a rigorous technique that can directly measure the stoichiometry as well as the equilibrium constants of an oligomer16. Unlike FRET, SE-AUC does not require the introduction of labels, which could potentially interfere. However, one important limitation of SE-AUC is that measurements can only be performed in detergent micelles. Therefore FRET has been particularly important for investigating the energetics of association of TM helices in lipid bilayers, which are a better approximation to the natural membranes in which these helices reside.

FRET: a powerful and versatile method for studying membrane protein interaction in vitro and in vivo

FRET uses proximity as a means to detect TM domain interactions, and is compatible with both detergent and lipid milieus. As mentioned, the incorporation of an artificial label can potentially alter the natural course of an interaction, but the effect of the labels can be accounted for with proper controls. FRET is an exceptionally versatile technique for studying the interactions between synthetic peptides labeled with organic dyes in artificial bilayer mimetics, as well to investigating proteins in live cells using fluorescent protein fusion constructs. Ranging from qualitative24 and quantitative25–28 ensemble average spectroscopic data, to kinetic time-lapse FRET measurements29,30, all the way to FRET under the microscope31–33 with sophisticated spatial and temporal resolution data, an extensive body of studies have been developed to study a variety of different interactions within a membrane34 – interactions between lipids, between lipids and proteins, and between proteins.

In this article, we review the use of steady state FRET in the literature to investigate interactions in membrane proteins, with a particular focus on the interaction of the single TM helices of bitopic membrane proteins. These oligomeric complexes have been a favorite system for investigating the rules that govern TM helix association35–39. In addition to being a tractable system, the bitopic membrane proteins attract interest because of their biological importance. These proteins comprise the most numerous class of membrane proteins (constituting about half of the total1,40,41), and their oligomerization plays important roles in assembly, signal transduction, ion conduction and regulation in a wide variety of biological processes as has been extensively reviewed39,41–44.

The discussion will begin with a brief introduction to fluorescence and FRET. We will then introduce the use of this technique in studying integral membrane proteins, and systematically cover the different model membranes and detergents used in these studies. This will include a discussion on the important contributions to this field to investigate specific proteins or protein families, or to improve upon existing FRET methodologies and formalisms, or both. In subsequent sections, we will enlist the common formalisms used to calculate FRET efficiency, and factors that can alter the observed FRET efficiency dramatically, including choices of fluorophores used. Finally Finally, we will discuss the utility of FRET to quantify the oligomeric state of integral membrane proteins, a task that is still challenging. The goal of this review is to provide the reader with a comparative summary of the relevant literature for planning and designing FRET experiments for determining TM helix-helix interaction. Table 1 provides a schematic overview of this literature, listing the membrane mimetics, the fluorophores, the FRET methods and the biological system that are the subject of these studies.

Table 1.

FRET studies of transmembrane helix association

| Donor | Acceptor | Hydrophobic Solvent | Forster radius | Biological system | FRET method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMCA | DABS-chloride | SDS micelles C12E8 micelles OG micelles DOPC vesicles |

49 ± 1 Å 48 ± 1 Å |

Phospolamban | Donor Quenching | 28 |

| DANS-chloride | DABS-chloride | SDS micelles C12E8 micelles OG micelles DOPC vesicles |

33 ± 1 Å 32 ± 1 Å |

Phospolamban | Donor Quenching | 28 |

| Pyrene | 7-dimethylaminocoumarin | SDS micelles DDMAB micelles DPC micelles |

60 Å | Glycophorin A | Acceptor Sensitization | 11 |

| Pyrene | 7-dimethylaminocoumarin | C12Sulfate, C12DMAB, C10,C11 Maltoside, C10,C11,C12DAO | Not used | Glycophorin A | Acceptor Sensitization | 50 |

| Fluorescein | TAMRA | DDM+SDS mixed micelles | 54 Å | Glycophorin A | Donor Quenching | 51 |

| Tyrosine57 | Tryptophan10 Tryptophan12 |

DOPC vesicles and SDS micelles | 13.2 Å 9 Å |

Bacteriorhodopsin | 91 | |

| NBD | Rhodamine | SDS micelles DMPC vesicles |

50 Å | EphA1 receptor | Donor Quenching | 97 |

| FITC | Rhodamine | SDS micelles | 55 Å | IRE1α | Donor Quenching | 119 |

| DANS-chloride | DABS-chloride | SDS micelles | Not used | Major coat protein | Donor Quenching | 100 |

| DANS-chloride | DABS-chloride | SDS micelles | Not used | ANTRX1 | Donor Quenching | 70 |

| FAM | TAMRA | SDS micelles PFO micelles |

Not used | Na,K-ATPase | Donor Quenching | 71 |

| 7-hydroxycoumarin | FAM/FITC | DPC micelles POPC vesicles |

Not used | FtsB, FtsL | Donor Quenching | 14 |

| 7-hydroxycoumarin | FITC | C14Betaine micelles | Not used | CHAMP peptides | Donor Quenching | 101 |

| DANS-chloride | DABS-chloride | SDS micelles | Not used | Model Aipep | Donor Quenching | 72 |

| DANS-chloride | DPBS-chloride | DHPC vesicles | 39 Å | Gramicidin A | Donor Quenching | 25 |

| DANS-chloride | DABS-chloride | DMPC vesicles | 40 Å | Glycophorin A | Donor Quenching | 26 |

| Fluorescein | TAMRA | DMPC, diC(14:1)PC, diC(16:1)PC, diC(18:1)PC, diC(20:1)PC, diC(22:1)PC | 49–54 Å | Glycophorin A | Donor Quenching | 52 |

| Fluorescein | Rhodamine | POPC vesicles | 55 Å | Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR3)-TM | Donor Quenching | 13 |

| Cy3 | Cy5 | POPC vesicles | 55 Å | FGFR3-TM | Donor Quenching | 13 |

| Fluorescein | Rhodamine | POPC,POPG,POPS vesicles | 56.1 Å | FGFR3-TM mutants | Donor Quenching | 65,66 |

| BODIPY-fluorescein | Rhodamine | POPC,POPG,POPS vesicles | 56.3 Å | FGFR3-TM ACH mutant | Donor Quenching | 12,65,66 |

| Fluorescein | Rhodamine | POPC vesicles | 56 Å | FGFR3-TM, Pathogenic Cys mutants | EmEx-FRET, Donor Quenching | 56,67 |

| EYFP | mCherry | CHO cell membrane derived vesicles | 53 Å | Glycophorin A | QI-FRET | 121 |

| EYFP | mCherry | CHO, HEK293T and A431 cell membrane derived vesicles | Not used | Glycophorin A | QI-FRET | 62 |

| EYFP | mCherry | HEK293T cell membrane derived vesicles | Not used | FGFR3-TM & ACH mutant | QI-FRET | 68 |

| EYFP | mCherry | CHO cell membrane derived vesicles | 53 Å | ErbB2 TM & oncogenic mutant | QI-FRET | 69 |

| Fluorescein | Rhodamine | DLPC, POPC vesicles | 55 Å | M2 | Donor quenching | 45 |

| Fluorescein | Rhodamine | DPC micelles | ~50 Å | major histocompatibility complex chains MHC and MHC | Donor quenching | 120 |

FRET: A tool to investigate membrane protein interactions

FRET to study macromolecular association

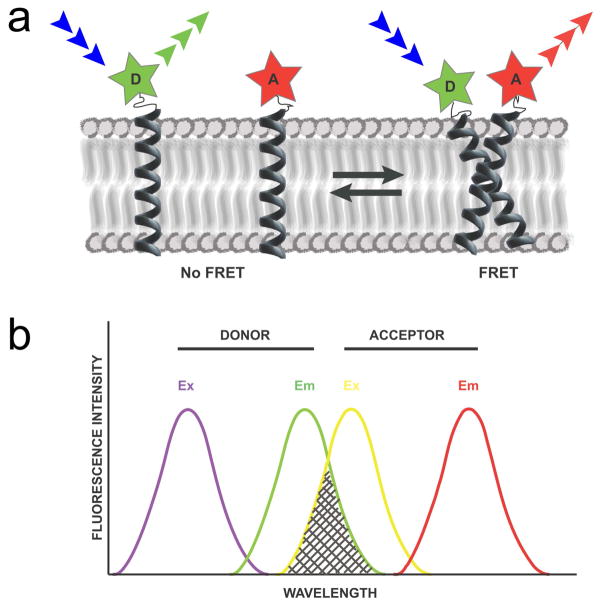

FRET is a photophysical process that is related to the phenomenon of fluorescence. FRET occurs when an electronically excited donor (D) fluorophore is quenched by a non-radiative energy transfer to an acceptor (A) chromophore in the vicinity instead of emitting fluorescence (Figure 1a). The acceptor chromophore does not need to be fluorescent but often it is – in which case FRET can be detected by increased fluorescence at the emission wavelengths of the acceptor. FRET is possible if the D-A pair has a dipolar overlap (the emission spectrum of D overlaps with the excitation spectrum of A, Figure 1b) and if the two fluorophores are within 10–100 Å of each other. This range depends on distance parameter, specific to each D-A FRET pair, called the Förster radius or (R0). The Förster radius is defined as the distance between D and A at which the FRET efficiency E is 50%, according to

Figure 1. FRET as a tool to study transmembrane protein interactions.

(a) Schematic representation of TM helices in a lipid bilayer, labeled with donor (D) and acceptor (A) fluorophores. Upon excitation (blue arrows) the donor fluorophore in isolation emits fluorescence at its characteristic wavelengths (green arrows). In a donor-acceptor dimer, the excitation energy can be transferred from the donor to the acceptor and FRET will manifest as an increase of acceptor emission (red arrows) and a decrease of donor emission. (b) Depiction of the excitation and emission spectra of a FRET pair. FRET occurs when the emission spectrum of the donor (green curve) overlaps with the excitation spectrum of the acceptor (yellow curve) with a good overlap integral denoted by the gray shaded area. A good FRET pair has a notable spectral overlap with minimal bleedthrough of the acceptor’s excitation into the donor excitation wavelength (overlap of the violet and yellow spectra), and minimal emission of the donor in the acceptor emission wavelength (overlap of the green and red spectra). Colors of the spectrum are a depiction of the increasing wavelength of light.

| (1) |

where r is the distance between the pair. Thus FRET measurements could in principle yield distance measurements between two fluorophores, although this is very difficult in practice. R0 can be calculated as

| (2) |

where Q0 is the quantum yield of the donor in the absence of the acceptor, J is the spectral overlap integral, n is the refractive index of the medium and K2 is the dipole-dipole orientation factor25. The calculated R0 values, assuming random fluorophore orientation, typically lie within the 15–60 Å range, which is comparable to the size of biological macromolecules (30–50 Å), and thus FRET has been widely used as an indicator of proximity to elucidate macromolecular association and major conformational changes.

FRET studies of TM interaction: progress over the years

Characterization of membrane protein interactions using FRET between labeled proteins or peptides has been already in use for over three decades. The earlier studies show examples of both qualitative and quantitative measurements. In 1977, a quantitative approach by Veatch and Stryer looked at the dimerization of gramicidin A25 and derived formalisms for distinguishing different oligomeric schemes. In 1982, Morris et. al., qualitatively used FRET to show that chromaffin granule membrane proteins form aggregates upon addition of calcium24. These early studies paved the platform for use and improvement of FRET techniques to study membrane proteins. In 1994, Adair and Engelman derived a model for the energy transfer within oligomers and used it to show that the glycophorin A TM domain formed a dimer, as opposed to a higher order oligomer26. This formalism has since then been widely used in quantitative FRET studies to confirm dimerization of TM helices. Further progress in assessing the oligomeric state was made by others, including formalisms applicable to higher oligomers28,45 (see the “Determination of the oligomeric state using FRET” section).

These earlier studies enabled quantification of the energetics of oligomerization, but did not account for the FRET contribution due to random proximity. Simulated by Wolber and Hudson in 197946 and later by Wimley and White in 200047, the proximity FRET term was for the first time included in membrane protein FRET efficiency calculation by Hristova and coworkers in 200513, and then further improved upon and extended to larger oligomers in 201448. A different formalism was also developed by Fernandes et. al. in 200849.

These different formalisms have been applied over the years to investigate many systems and different problems involving interacting TM helices. For example, the Engelman11,26,50 and the Schneider groups51–54, have have used FRET to study the dimerization of the model system glycophorin A (GpA) and its sequence variants in different membrane mimetic environments. The Hristova group has contributed significantly to the field of FRET in membrane proteins by developing new experimental methodologies55,56,56,57, testing different bilayer environments13,58–62, and improving on existing formalisms for FRET calculations13,48,63 to investigate the dimerization of proteins of the receptor tyrosine kinase family12,64,43,65–69. Deber and coworkers have studied oligomerization of natural and model peptides to understand the structure-function relationship of receptors70, ion pumps71 and other biological system, and to investigate the rules that govern membrane protein folding72. These and many other investigations over the years have proved FRET to be one of the most important tools to characterize the interaction of membrane proteins, and yielded invaluable understanding of folding, association and structure.

FRET studies of TM interactions in lipid and detergent

Solvent for membrane protein studies: detergents, lipids and other lipid mimetics

Membrane proteins are highly hydrophobic and are generally not soluble in aqueous solutions. Thus, in order to investigate the structure and thermodynamic of properties of these proteins in vitro, using any technique, they first need to be reconstituted into environments that mimic natural membranes. Considering the complex constitution of the membrane, it is difficult to replicate the exact conditions for these proteins in an artificial milieu. Nonetheless, tremendous progress has been made to design membrane mimetics that solubilize membrane proteins in vitro for their structural and functional characterization (Figure 2)73,74.

Figure 2. Artificial environments for membrane protein solubilization.

(I) Transmembrane helices can be incorporated in micelles made of a single detergent (top), or by mixtures of different detergents or detergents and lipids to form mixed micelles (bottom). (II) Lipid bilayers in the form of unilamellar (top) or multilamellar (vesicles). (III) Two types of discoidal bilayers, bicelles, which are bilayers stabilized by short chain lipids at their edges (top) and nanodiscs, stabilized by membrane scaffolding proteins (bottom). Figures not drawn to scale.

The most widely used membrane mimetics for studying membrane protein oligomerization are lipid bilayers and detergent micelles. Bilayers – which are a more native-like environment – can be synthetically prepared by different methods: in the form of supported bilayers61, multilamellar vesicles13, and giant (~500 nm), large (~100 nm) or small (~30–50 nm) unilamellar vesicles. As discussed later, these alternative forms may be best suited to different experimental requirements73,74. Another option is the nanodiscs75, which are more stable bilayer mimics compared to liposomes because they are small particles encased by a membrane scaffold protein that surrounds and holds together the lipids. They can be prepared in 6–30 nm diameter sizes based on the scaffolding protein derivative used. Finally, bilayers can also be prepared from natural membranes, such as rough endoplasmic reticulum microsomes76 and plasma membrane derived vesicles62. These bilayers contain all of the components of a natural membrane.

A bilayer is an ideal membrane mimetic for FRET studies of membrane proteins. However, lipid bilayers are at times difficult or impossible to use because of challenges with achieving proper equilibration of the samples, along with light scattering artifacts that may affect fluorescence measurements. A less ideal but more convenient alternative are detergents. Like lipids, detergents are amphipathic molecules consisting of a polar head group and a hydrophobic tail; however, instead of bilayers, detergents form globular micellar structures in aqueous solutions. Because of their smaller size, detergents do not produce scattering artifacts and are in general easier to handle. As long as their concentration in solution is above its critical micellar concentration (CMC), detergents can generally solubilize a membrane protein and serve as a hydrophobic solvent.

A vast array of detergents with distinct physical-chemical properties can be chosen from to optimize conditions for a specific protein and application74,77–79. Although detergents can conveniently solubilize membrane proteins, they can also destabilize the proteins over time. In an effort to design less destabilizing solvents, compounds called tripod amphiphiles80,81 and amphipols53,82 have been developed and used for solubilizing membrane proteins. These compounds designed to keep membrane proteins active over periods of time and have been useful in structural investigations using NMR and X-ray crystallography. In certain situations, a combination of detergents and lipids to form mixed micelles51 and bicelles83 (small discoidal lipid bilayers whose edges are stabilized by short-chain lipids) can be employed and has been useful in many structural investigations of membrane proteins.

Hydrophobic environment properties affect helix-helix association

Investigations of TM peptides in detergents and lipids have enabled identifying key residues involved in helix-helix associations, and contributed greatly to our understanding of the factors that influence the energetics of association in membrane proteins. The TM domain of GpA (GpA-TM) has been a major paradigm in such studies, and the very first systems investigated using FRET in a pioneering investigation that used dansyl and dabsyl labeled peptides in DMPC multilamellar vesicles26 (the study was more precisely designated as ‘RET’ because the acceptor dabsyl is non-fluorescent). Numerous studies in lipids and detergents have followed this initial work to better understand the thermodynamics of GpA-TM dimerization as well as the environment influences membrane protein interactions. For example, FRET was used to investigate the effect of different types of detergents on the GpA-TM association11,50. The GpA-TM dimer was observed to be two orders of magnitude less stable in SDS than in zwitterionic detergents DDMAB and DPC, demonstrating that environment has an important role to play in association11. The time taken to reach steady state equilibrium also depended on the type and concentration of the detergents used. A follow up paper expanded on the previous study by studying GpA-TM dimerization in a series of detergents with varying alkyl chain lengths, combined with ionic, nonionic, and zwitterionic headgroups50. The results suggested that dimerization of GpA-TM in detergents is influenced by two opposing effects: an enthalpic effect – which drives association with increasing detergent concentration and which is sensitive to the detergent headgroup chemistry – opposed by an entropic effect – which drives peptide dissociation with increasing detergent concentration. Thus this study begun shedding light on the importance of detergent selection and how they can influence the association equilibrium of helical dimers.

While these studies focused on the effect of detergents with different head group chemistry, a clear relationship between the alkyl chain length and strength of dimerization was not observed. A much later study investigated the effect of aggregation number, or number of detergent monomers per micelle, on TM helix dimerization. FRET measurements using labeled GpA-TM peptides were carried out on lyso-PC micelles of varying acyl-chain lengths to investigate the effect of detergent concentration, aggregation number and the micelle’s hydrodynamic radius on TM association54. It was observed that the dissociation of the GpA-TM dimer did not correlate to dilution in detergent, indicating an influence of the detergent properties on dimerization. Further, GpA-TM dimerization did not depend on the similarity of the detergent’s hydrodynamic radius to the hydrophobic length of the TM domain; in fact the oligomerization was destabilized with increasing chain length, opposing the assumption that longer chains render the detergents milder. Moreover, the detergent molecules in a micelle seemed to be able to match the hydrophobic length of the peptide, suggesting that the concept of hydrophobic match/mismatch of TM helices to lipid membrane systems84 may not be translated to detergent systems. One the other hand, the effect of acyl chain length of lipid vesicles had a direct correlation with GpA dimerization in different lipid vesicles with varying carbon chain lengths52. Unlike the observation for the lyso-PC detergents, the acyl chain length was found to severely influence the dimerization of the TM domain, being most efficient under hydrophobic length matching conditions. Dimerization efficiency was highest in the C20 (30.5 Å) and C22 (34 Å) chain length lipids, comparable to the hydrophobic length of GpA (31–32.2 Å, according to the NMR structure of the TM dimer85 and the theoretical prediction of the OPM database86). This, again, demonstrated how different environments play a role in the association of a TM protein.

FRET used to study ‘unfolding’ of TM proteins

To study reversible folding of membrane protein systems, conditions are required that push the equilibrium to the dissociated state. This can be achieved by diluting peptide concentration in the hydrophobic volume as performed in typical FRET experiments. Apart from dilution in the same detergent or lipid, unfolding studies of TM helix association using FRET have also been attempted by changing the hydrophobic environment from a more stable to a less stable state. A first report of the utility of mixed micelles using GpA as a dimerization standard51 provided evidence that unfolded/unassociated membrane proteins retain a majority of their helical content, as postulated by the Two-Stage Model of membrane protein folding8. Labeled GpA TM peptides, were reconstituted in the mild non-ionic DDM micelles, where they were helical as well as dimeric as observed by FRET. Keeping the total peptide:detergent ratio constant, SDS was added such that the mole fraction of SDS relative to DDM increased. SDS is a harsh, negatively-charged detergent shown to denature most polytopic membrane proteins, but it retains the oligomeric states of some TM helices in the low millimolar concentrations18,87–90. It was observed that with increasing mole fraction of SDS, there was a decrease in FRET but not helicity of the sample (observed by CD), indicating dissociation of the dimer to form helical monomers in mixed micelles51.

In a similar unfolding study, two TM helices of bacteriorhodopsin that are known to associate (helix A and helix B) were transferred from DOPC bilayers to SDS micelles91. This study involved the use of intrinsic FRET from a tyrosine on one peptide to two tryptophan residues on the other peptide. FRET efficiency was reduced from transferring the peptides from DOPC to SDS micelles, suggesting a loss of association, interpreted as unfolding of the peptides from DOPC bilayers to SDS micelles. However, MD simulations in the same study suggested that a small rearrangement of the peptide backbone in the SDS micelles could result in easier access of water molecules into the micelles. This water could form hydrogen bonds with the donor (Tyr), which could decrease the quantum yield and contribute to a decrease the FRET efficiency.

The authors also argued that use of mixed micelles in TM helix unfolding may be overlooking the effects of increased surface charge density of the negatively charged SDS micelles51, which may affect the properties of dyes such as fluorescein and TAMRA, which are environmentally sensitive92. This study highlights one of the complexities of using FRET to study membrane proteins where changes in the hydrophobic environment can affect the chromophores and contribute a change in the FRET efficiency. In such situations, control experiments using different fluorophores or with alternative biophysical methods could help recognize the influence of these undesired environmental effects.

Comparing stability in lipids and in detergents using FRET

As the lipid bilayer is closer to the natural membrane in comparison to detergent, it is expectable that the oligomeric complexes may be better behaved and more stable in the former. This distinction has been demonstrated using FRET in different systems. The oligomeric state of phospholamban (PLB), a 52 amino acid protein in the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum that regulates the cardiac calcium pump, was investigated both in detergent and in lipid bilayers28,93. It was previously shown that PLB forms homopentamers in SDS micelles 94,95. An electron plasmon resonance (EPR) study96 showed that the average oligomeric size of PLB changed from 3.5 to 5.3 upon its phoshorylation, suggesting a dynamic equilibrium between PLB subunits in lipid bilayers. This suggested that there might be oligomeric changes involved in the regulation of the pump, but the EPR method could not resolve the multiple oligomeric species. Using fluorescent donors (AMCA and DANS), and a non-fluorescent DABS acceptor attached to recombinant PLB protein, Li et al. analyzed the PLB oligomeric states in detergents and lipids28. The various detergents yielded to different observations in terms of the extent of oligomerization, the oligomeric state and the proximity of adjacent subunits. Moreover, a marked difference in sample equilibration was observed between lipid (DOPC) and the detergents. Equilibration occurred readily in lipid, whereas a boiling step was required to observe efficient subunit exchange between the complexes in detergents. Once again, these observations demonstrate how the environment can play a role in the association of TM proteins.

Other FRET studies of oligomerization have demonstrated that TM helix interactions can be more stable in the lipid bilayer. FRET efficiency values indicated that the dimerization of the TM domain of the EphA1-receptor was more stable in DOPC bilayers than in SDS97. Similarly, the formation of homo- and hetero- oligomers of the bacterial divisome proteins FtsB and FtsL demonstrated that all complexes were more stable in POPC vesicles than DPC micelles14. The weaker oligomerizing tendency in DPC of the FtsB TM peptide (which has been previously been shown to self-associate in native bacterial membranes98), suggested that the contribution of a hydrogen bond formed by a glutamine residue at the FtsB interface may be weakened by the increased ability of this polar residue to interact with water molecules in the micellar environment.

FRET in detergent as a complementary assay

In spite of the higher stability of TM peptide oligomers in lipid, detergents pose a very convenient means for these experiments. FRET in detergent micelles has aided the study of the interaction of many TM helix systems. These studies have often been performed in coordination with other methods such as coimmunoprecipitation, PAGE, Western blot, TOXCAT99, and SE-AUC to study a variety of membrane protein systems. For example, Deber and coworkers have associated FRET with the aforementioned techniques to study the homodimerization of the TM domain of the major coat protein of Ff bacteriophage in SDS micelles100; the oligomerization of the Na,K-ATPase (sodium pump) TM domain in PFO micelles (a detergent that retains association for weakly interacting helices)71; and the TM self association of the anthrax toxin receptor ANTRX1 in SDS micelles70. In addition to these biological systems, they also studied a model helix-loop-helix peptide made of Ala and Ile residues in SDS micelles to investigate the nature of van der Waals forces and side-chain hydrogen bonding networks in TM peptide interactions72.

FRET in detergent micelles has also aided computational design. An example is the experimental characterization of the association of Computed Helical Anti-Membrane Protein (CHAMPs) peptides to their target, which are capable to bind specifically to TM-helices in a similar fashion to antibodies of water soluble proteins101. The fluorophores and experimental conditions used in all the above mentioned studies are listed in Table 1.

Choices of lipid environments: artificial bilayers

Different forms of artificial lipid bilayers are suitable for FRET studies of TM helix interaction: multilamellar or unilamellar vesicles of varying sizes, and planar supported bilayers. The multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) are prepared by hydration, vigorous agitation and freeze-thawing of hydrated peptide/lipid films, which are obtained by evaporation from organic solutions13–15. It was observed that the presence of TM peptides decreases the turbidity of MLVs after just one freeze thaw cycle. This change was not observed for free lipids13, indicating that the presence of peptides facilitates formation of smaller MLVs in the 1:100 to 1:10000 peptide:lipid relative molar range, making FRET experiments in these vesicles feasible. Extrusion of MLV’s using a 100 nm diameter membrane (Avanti) produces large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs). Sonication of the extruded LUVs creates 30–50 nm small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs). While the fluorescence of the TM peptides tends to be stable over a long period of time in MLVs and LUVs, it decreases more rapidly in SUVs indicating a higher tendency to aggregation of the TM peptide.

In theory the unilamellar vesicles have the advantage to rule out any spurious FRET contributions arising from TM peptides in consecutive leaflets of an MLV. It has been shown, however, that there is no statistically significant difference between FRET efficiencies obtained from MLVs and LUVs. Extrusion can also cause a loss of peptide as well as lipid, but this loss is to a similar extent in both, and thus does not affect the FRET efficiency (which is a function of the peptide:lipid ratio)13. Among these choices, the MLVs are the most practical for their stability and short preparation time, and thus represent a good hydrophobic environment to investigate TM helix-helix interactions for bulk FRET studies13,14.

Another synthetic bilayer platform developed and extensively used by the Hristova group is the surface supported bilayer, where peptides are reconstituted into a single leaflet of lipid at the air/water interface, transferred onto glass substrates, then fused with lipid vesicles to form the second leaflet of the supported bilayer and imaged under a microscope12,58–60. This ‘directed assembly’ of the peptides into the bilayers is different from the previously designed ‘self assembly’ of peptide containing liposomes on glass surface102, and offers several advantages over it. First, it requires 1/100th the amount of peptide needed for reconstituting in bilayer vesicles in solution before assembling them on the glass surface, thereby reducing the material cost of the experiments. Secondly, it allows more control over achieving unidirectional orientation of the peptides. The peptides are deposited on a single lipid monolayer first, and can be oriented according to a certain topology by ensuring that the TM region is flanked on one side by charged water soluble residues, and on the other side by neutral hydrophilic residues58.

Instrumentation advances have also contributed to expanding the range of conditions in which these supported bilayers can be applied to measuring association of membrane proteins. Hristova and colleagues initially developed the techniques relying on fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), using acceptor photobleaching as the observed parameter102. Fluorescence was measured using a microscope (‘imaging FRET’). The method was later adapted to allow the measurement of fluorescence in supported bilayers using a standard spectrofluorimeter (‘spectral FRET’)59. Use of the ‘spectral FRET’ technique does not require the stringent conditions imposed by FRAP, which necessitates that the peptides in the bilayer diffuse slowly and that the fluorophores are photostable. Moreover, detection with a spectrofluorimeter allows one to record the entire spectra, as opposed to fluorescence intensity within a narrow wavelength range determined by the choice of emission filters, as in ‘imaging FRET’. These developments enabled a wider selection of FRET pairs (as reported in Table 1), including pairs such as fluorescein/rhodamine that have greater spectral bleedthrough and lower photostability, but are more commonly used for their ease of labeling, cost-effectiveness, and favorable Förster radius for TM helix interactions59,103. The Hristova group has integrated the use of all the types of bilayers described above – LUVs, MLVs and surface supported bilayers – to study TM interactions of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) FGFR3 and its sequence variants12,56,43,65–67,104.

Choices of lipid environments: plasma membrane derived vesicles

Although artificial bilayers have enabled thorough investigations of membrane protein association energetics using FRET, one caveat is that the interactions are assayed in a non-native ‘dilute’ system. In the cell membrane, protein-protein interactions occur in a crowded environment, with a high local concentration of other proteins. In vitro experiments with artificial bilayers ignore the ‘excluded volume effect’ described for soluble proteins, which explains how macromolecules inside a cell occupy 20–30% of the cell volume, exerting non specific effects on the interactions105,106. This type of crowding also occurs in the membrane with other proteins in the vicinity and could either increase the probability of association or prevent specific associations of membrane proteins in the local membrane environment. This supports an argument that working in artificially dilute conditions, for any macromolecular interaction study, is associated with a risk to obtain results that are physiologically irrelevant107.

To account for this crowding factor, Hristova and coworkers developed a quantitative FRET imaging technique, ‘QI-FRET’57 that used microscopy to measure TM interactions in cell-derived vesicles that contain the native cytoplasmic milieu. Using this technique, they found that the GpA-TM dimer is in fact weaker in mammalian membranes63 than previously established using various techniques11,18,26,50,99,108–111, suggesting that molecular crowding indeed plays a role in the energetics of protein-protein interactions. They further established that the dimerization of GpA-TM is not statistically different in a variety of six different plasma membrane derived vesicles, prepared from different cell lines using different methods62 suggesting that any of these cell lines could be used for TM domain interaction studies using QI-FRET. QI-FRET was also applied to investigate oligomerization of members of the RTK family oligomerization. Among the findings, it was determined that a disease-causing mutation in the TM domain of FGFR3 has altered dimerization68, and that the ErbB2 TM domain shows the highest dimerization strength amongst the RTKs in mammalian membranes69. A list of the various mammalian membranes used in these studies is provided in Table 1.

Calculation of energetics of association from FRET efficiency

The FRET efficiency (E) is the fraction of energy from photons absorbed by the donor that is transferred to the acceptor112. Energy transfer occurs only when two fluorophores are at a distance that is near or below the characteristic Förster radius. As such, the FRET efficiency can be used as a reporter of intermolecular interaction.

In the simplest case of a dimeric complex, the amount of observed FRET Eobs is theoretically directly proportional to the relative amount of dimer complex according to

| (3) |

where [d] is the concentration of the dimer, [m] is the concentration of the monomer and Emax is the maximum theoretical FRET efficiency. The monomer and dimer fractions can be then used to derive the apparent equilibrium constant and free energy of association.

| (4) |

| (5) |

The maximum theoretical FRET efficiency, Emax, is the FRET of a sample in which the equilibrium is completely pushed toward the dimeric form. Emax depends on the relative concentration of dimer formed by a donor (D) and an acceptor (A) peptide, over all possible other combinations of dimers that involve a donor. Emax depends also on the presence of any unlabeled peptide (U), which will also participate to the equilibrium competing with the observable donor-acceptor pair.

| (6) |

The concentration of unlabeled peptide depends on the labeling efficiencies of donor and acceptor samples. The maximization of labeling efficiency is a critical factor for a successful FRET experiment. As discussed later, the equilibrium models should also take into account any contribution to FRET by peptides that co-localize randomly due to diffusion but are not engaged in a specific complex (proximity FRET).

The simple formalisms

The basic measurement of FRET efficiency requires at least three different samples for every peptide concentration used; the ‘donor only’ sample, the ‘acceptor only’ sample, and the ‘FRET sample’, containing a mixture of donor and acceptor labeled peptides (Figure 3). Primarily, three different techniques have been used to measure the FRET efficiency of TM helix-helix oligomerization.

Figure 3. Control samples in a FRET experiment.

(a) ‘Donor Only’ sample: peptides labeled with donor fluorophores are excited with donor excitation wavelength (blue arrows) and exhibit donor fluorescence (green arrows). (b) ‘Acceptor Only’ sample: peptides labeled with acceptor fluorophores are excited with donor excitation wavelength and show no red fluorescence (minimal spectral bleedthrough). (c) ‘FRET sample’: peptides with equimolar donor:acceptor peptide ratio, with the same total peptide:lipid ratio excited with donor excitation wavelength exhibit acceptor fluorescence (red arrows) due to FRET arising from TM peptide association, and show decreased donor fluorescence (green arrows).

The first technique is Donor Quenching. This approach relies on the decrease of the direct emission of the donor that results from the energy transfer to the acceptor. Utilizing the ‘donor only’ and the ‘FRET sample’, the apparent FRET efficiency Eapp is calculated from the intensity of donor emission when acceptor is present (IDA) and when it is absent (ID), according to:

| (7) |

The fluorescence intensity is generally measured at the emission maximum wavelength λmax of the donor (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Calculation of the FRET efficiency.

The green curve represents a fluorescence spectrum of the ‘donor only’ sample, representing the donor emission spectrum at the donor’s excitation wavelength. The red curve represents a spectrum of the ‘acceptor only’ sample from direct excitation of the acceptor at the donor’s excitation wavelength, due to spectral bleed-through (direct excitation of the acceptor at the donor’s excitation wavelength). The black curve represents an emission spectrum of the ‘FRET sample’ containing a mixture donor and acceptor, excited at the donor’s excitation wavelength. FRET efficiency can be calculated either by monitoring the decrease in the donor’s emission intensity (indicated by downward arrow) or by monitoring the increase in the acceptor’s emission intensity (indicated by the upward arrow).

The second method is Acceptor Sensitization, which measures the increase in acceptor emission, or “sensitization”. Since in most cases there is some direct excitation of the acceptor (IA) when excited at the donor excitation wavelength (Figure 4), this contribution needs to be subtracted from the acceptor emission (IAD) measured from the ‘FRET sample’. The apparent FRET efficiency is then given by

| (8) |

where εD and εA are the molar extinction coefficients of the donor and the acceptor at the donor’s excitation wavelength113. The acceptor sensitization method is most useful when using a FRET pair such as pyrene and coumarin. Pyrene has a high quantum yield and narrow bands (Figure 5a), making it easier to detect energy transfer through sensitized acceptor emission. In Figure 5c, the emission detected at 500 nm is plotted as a function of excitation wavelength. The intensity due to direct emission of the donor is minimal, and a large increase in the excitation intensity between 300–350 nm indicates a strong FRET signal. Another advantage of the pyrene/coumarin pair is that the presence of the donor affects neither the relative fluorescence nor the wavelength of the acceptor maximum (378 nm), allowing it to be used as an internal standard for acceptor concentration during the FRET measurements.

Figure 5. Demonstration of Sensitized Emission using pyrene and coumarin labeled peptides.

The fluorescence spectra shown are that of Glycophorin A peptides labeled with pyrene (donor) and coumarin (acceptor) in DDMAB detergent. (a) Pyr-GpA: Excitation spectra (—) recorded at 378 nm emission wavelength, and emission spectra (– – –) recorded at 345 nm excitation wavelength. (b) Cou-GpA: Excitation spectra (—) at 460 nm emission wavelength and emission spectra (– – –) at 378 nm excitation wavelength. (c) Excitation spectrum of a ‘Donor only’ sample (- - -), an ‘acceptor only’ sample (– – –), and a 1:1 donor:acceptor ‘FRET sample’ (—) recorded a 500 nm emission wavelength. Sensitized emission was observed by an increased intensity of the Pyr-GpA (donor) excitation spectrum in the ‘FRET sample’ compared to that in the ‘donor only’ sample. Cou-GpA (acceptor) spectrum was unaltered between the ‘acceptor only’ and the ‘FRET sample’. Reproduced from Fisher et al.11 with permission from Elsevier.

One of the uncertainties associated with FRET measurements is the variation in the effective peptide concentration from one sample to another, which is a particularly important issue working with hydrophobic TM peptides. The EmEx-FRET technique reduces these uncertainties by calculating the concentrations of the donor and acceptor labeled peptides from the fluorescence spectra obtained56. In this technique, the excitation and the emission spectra for the ‘FRET sample’ are obtained and normalized to the excitation and emission spectra of ‘donor only’ and ‘acceptor only’ samples of known concentrations (standards), using a scaling coefficient factor. This coefficient factor is multiplied by the known standard concentrations to get the donor and acceptor concentrations in the ‘FRET sample’56,103.

Which method should be used to calculate FRET efficiency?

The most commonly used method for membrane proteins is donor quenching, as is reflected in Table 1. Although acceptor sensitization provides a more direct measurement, it requires characterization of the acceptor’s extinction coefficient in the detergent or lipid being used, which is non-trivial for less photostable environmentally sensitive dyes.

The EmEx method of FRET provides a more precise measurement by actually measuring the effective concentration of both the donor and acceptor labeled peptides during the fluorescence acquisition. This method requires the FRET pair to have a wavelength range where the acceptor’s excitation spectrum in the presence and absence of the donor is the same, a feature of common pairs such as fluorescein-rhodamine and Cy3-Cy5, but also fluorescent proteins such as EYFP-mcherry. Moreover, the EmEx concept – which has been adapted for cell-derived vesicles as the quantitative imaging of ‘QI-FRET’57 – can also be used in cellular studies where the donor and acceptor concentrations are unknown. This technique was developed using the FGFR3-TM peptides in POPC vesicles56, and subsequently extended to FRET microscopy to yield the quantitative imaging or ‘QI-FRET’ method that allows the determination of the donor and acceptor concentrations as well as FRET efficiency in cell-derived vesicles57,62,63,68. However, the QI-FRET imaging technique measures the integrated intensity of fluorescence over a particular bandwidth of an optical filter, and not the full spectrum as opposed to that obtained from a fluorimeter. Therefore, while this method provides the most physiologically relevant measurement of FRET efficiency of membrane proteins, adaptation of this method to obtain fluorescence spectra instead of integrated intensities may provide a more quantitative analysis of the interaction energies of association.

In summary, the choice of method used therefore depends on the nature of the investigation, and may be narrowed down to ‘donor quenching’, the ‘EmEx’ and the ‘QI-FRET’ methods as the most practical choices. For qualitative applications, the donor quenching method is straightforward, and fastest, and can also be used for quantitative analyses along with the use of proper controls13. For a more rigorous study of the energetics of TM helix association, the EmEx method serves as a precise technique that can provide measurements in artificial bilayers in a fluorimeter, and can be used with a wider array of FRET pairs to choose from, and the QI-FRET method extends this analysis to proteins in native mammalian cell-derived vesicles with the help of confocal microscopy.

Non-specific proximity contribution to FRET

For a thorough quantification of FRET efficiency, another important parameter is the contribution due to random colocalization rather than association. Studies of interactions between TM helices are usually performed in sufficiently dilute conditions (i.e. low peptide:lipid ratios) so that the average distance between individual peptide molecules is greater than the Förster radii of the dyes they are attached to. Nevertheless, free diffusion of the peptides will allow an extent of random colocalization of donor and acceptor molecules that cohabitate the same lipid vesicle. Thus the observed FRET (Eobs) will contain a contribution of proximity FRET (Eproximity).

| (9) |

The FRET due to random proximity was not included in the earlier quantitative models25,26,28. This contribution factor was first simulated for randomly distributed peptides, whose donor quenching by different acceptors in various acceptor configurations was averaged for different Förster radii46,47. The proximity term is given by:

| (10) |

where ri is the distance between the donor and the i-th acceptor, and R0 is the Förster radius for the FRET pair. This proximity FRET term was then used by Hristova and coworkers13 to separate the signal due to sequence specific interaction from random colocalization in lipid bilayers. The application of this factor demonstrated that there is a marked contribution of proximity to the observed FRET, with higher contribution for FRET pairs having higher R0 values, even at low acceptor mole fractions13. It was also observed that FRET due to donors and acceptors between two consecutive leaflets of an MLV is relatively small, even for higher R0 values, confirming that use of MLVs does not increase substantially the contribution of proximity FRET.

These proximity simulations considered the organic fluorophores to be point structures negligible in size, thus they are not applicable to large (3–4 nm) fluorescent proteins, which have a limited distance of closest approach. A model that did take the size factor into account, developed the proximity contributions for monomeric fluorophores of a finite size114, but not for those attached to oligomeric membrane protein complexes.

For cellular FRET studies, the fluorophores primarily used are large fluorescent proteins (FPs). These fluorophores participate in oligomeric structures where the probability of ‘background FRET’115 from a ‘bystander protein’116 in a crowded environment is quite high. King et al.48 predicted the proximity FRET over a wide range of exclusion radii of fluorophores and a thorough range of acceptor concentrations. They also simulated the proximity FRET for monomers (which they verified experimentally using plasma membrane derived vesicles), dimers, trimers and tetramers for the first time; and generated a model for the proximity FRET contribution as a function of oligomeric state and geometry of membrane protein complexes in a cellular scenario.

A different formalism of separating the proximity and specific interaction terms, argued to be more accurate34, has been used as well where the both the FRET and proximity contributions are multiplied and integrated to obtain the donor fluorescence decay, instead of the proximity contributions being subtracted while using the steady state donor quenching49.

Beyond the quantification of the contribution of FRET due to specific interactions, a practical control to determine whether the observed FRET is primarily due to sequence specific interactions is the addition unlabeled peptides to the ‘FRET sample’, which should result in a decrease in FRET by competition13,14. For instance, in the case of a dimeric interaction, if the addition of an equimolar amount of unlabeled peptide results in a FRET decrease of approximately 50%, it would indicate that the observed FRET is not majorly affected by unwanted effects such as colocalization, donor self quenching, improper equilibration, or interference from labels11,72. A useful additional control is the addition of the same amount of an unrelated peptide, which theoretically should not result in significant change of FRET. (Note: the actual theoretical decrease in these competition experiments depends on the total peptide concentration and the dissociation constant, because the addition of unlabeled peptide increases total peptide concentration).

Choice of fluorophores

An important parameter affecting the observed FRET efficiency is the nature of the fluorophores involved. An ideal FRET pair is one that has good spectral overlap, high photostability, high dynamic range and minimal spectral cross-talk. One of the first decisions is whether to prepare TM domain fusion constructs with fluorescent proteins, or to chemically synthesize the TM domains and label them with small fluorophores. Genetically encoded fusions with fluorescent proteins (FP) are faster and more cost-effective than synthesizing peptides and labeling them with small fluorophores; they also pose the advantage of conferring solubility to the hydrophobic TM domain during over-expression and purification. However, as can be seen in Table 1, use of FP fusion is not common unless the study is performed in cell-membrane derived vesicles, because of the low FRET dynamic range, poor maturation and reversible and irreversible photobleaching of FPs. Although efforts to improve upon the most standard FP FRET pair (CFP and YFP) are constantly ongoing117,118, use of organic fluorophores has been the most common in in vitro studies on transmembrane proteins.

Fluorescein is a widely used fluorophore, more commonly as a donor, such as in the fluorescein-rhodamine pair, but also as an acceptor, as in the coumarin-fluorescein pair. With an R0 value of ~55 Å, the fluorescein-rhodamine FRET pair is desirable because it can yield a FRET efficiency of up to ~99% for a typical parallel helical bundle, which has a much smaller inter-helical distance of 10 to 20 Å. As a donor, fluorescein can have a problem of self-quenching due to its overlapping excitation and emission spectra, but control experiments can be carried out to rule out that contribution as shown by You et al.13. Fluorescein is used as an acceptor in the coumarin-fluorescein pair. Its Förster radius, however, has not been well characterized in detergent or lipid, resulting in uncertainty regarding the maximum FRET efficiency that can be observed. Nevertheless, this FRET pair has been used in applications, with the use of donor quenching to calculate FRET efficiency14,101.

An alternative fluorophore that is more photostable and does not exhibit self quenching due overlapping excitation and emission spectra is Cy3, which forms a FRET pair with Cy5 with a comparable R0 value to fluorescein-rhodamine. However, as can be seen in Table 1, this FRET pair is not very widely used for membrane protein experiments. The low adoption of this pair is mainly due to cost. Labeling of hydrophobic TM peptides is difficult and requires large excess of dyes (~12 equivalents) to achieve maximum labeling efficiency14,55, which can render the use of the costly Cy3 and Cy5 dyes prohibitively expensive.

Other FRET pairs such as pyrene-coumarin11,50 and DANS-DABS26,28,70,72,100 have also been commonly used and have served as good FRET pairs for membrane protein interaction studies.

Determination of the oligomeric state using FRET

FRET is most suited to investigations of pairwise donor-acceptor interactions, nevertheless a number of models have been developed to utilize FRET for the determination of the oligomeric state of Tm complexes.

Using the fluorescence quantum yield of the donor as a function of the mole fraction of acceptor (keeping the total peptide:lipid ratio constant), Veatch and Stryer were the first ones to postulate the different signature curves for different oligomeric schemes (dimer, trimer, tetramer) of membrane proteins in lipid25. They also demonstrated how the equilibrium constant can be determined from the characteristic quenching curve of the donor as a function of the acceptor mole fraction once the number of subunits has been defined, and how the slope of the curve can be correlated to a preference for either donor-donor and acceptor-acceptor (homo-pairs) pairs over the productive donor-acceptor ‘FRET sample’ (hetero-pair). However, while the FRET data best supported a dimeric state for gramicidin A TM channel in DHPC vesicles, complementary conductance measurements were necessary to rule out possible trimer and tetramer models, which exemplify the difficulties in assessing the size of an oligomer by FRET alone.

In 1994, Adair and Engelman26 derived a dependency of the donor quenching on the acceptor mole fraction, showing that a linear relationship between the two was consistent with a dimer model for GpA in DMPC vesicles. Working under assumptions that there was no preference between homo-pairs, hetero-pairs and pairs with unlabeled peptides, they demonstrated that the data had a better fit to a dimer model (0.97 R2) as opposed to that of a trimer (0.68 R2). This relationship has since been widely used to elucidate the oligomeric state of many membrane protein complexes in lipid and detergent52,64,72,97,100,119. It is important to note that oligomeric state predictions obtained by these FRET experiments were, in all cases, complemented by investigations with other techniques. For example, the non-linear dependency of FRET on the acceptor mole fraction observed for the IRE1 TM domain fit well to a tetramer model, but this result was further corroborated by SDS-PAGE analysis, which displayed a band with an apparent molecular weight compatible with such an oligomer.119

The formalisms of Veatch and Stryer25 and Adair and Engelman26 – which work under the approximation of equal energy transfer to all subunits in an oligomer – are theoretically applicable to elucidating higher order oligomeric states. However, in the literature, they have been applied primarily to dimerizing complexes.52,64,72,97,100 This is likely because the linear relationship between FRET efficiency and the mole fraction of the acceptor holds only in the dimer case, and because the shift between the theoretical curves is much more marked in the dimer-trimer transition than in the transitions between trimer-tetramer, tetramer-pentamer, and so on.

A more complex formalism that in principle accounts for the contribution of all subunits, taking into account the geometry of a higher order oligomeric complex, was developed by Thomas and coworkers28. This model, which does not assume equal energy transfer between all subunits, was applied to phospholamban, a regulator of the Ca2+ cardiac pump. The FRET efficiency of each donor-subunit to each acceptor-subunit was calculated explicitly, assuming a ring like structure, and the dependency of FRET on acceptor mole fraction was simulated for 2 to 11 subunits. The data showed that in DOPC, phospholamban was in dynamic equilibrium, and the analysis indicated that the predominant forms had 8–11 subunits, in disagreement with the physiological pentameric form. This work exemplifies the difficulties in differentiating between higher order oligomeric states using FRET due to uncertainties in peptide concentration, labeling efficiency, and the position, orientation and mobility of the fluorophore as well as effects of the local environment on their quantum yield, all of which can severely affect the modeling. Nevertheless, such theoretical models can be applicable to cases in which the oligomeric state is known, such as an analysis of the relative stability of the M2 channel tetramer in different bilayers45.

FRET can also be used to obtain the stoichiometry of a heteromeric complex. This has been demonstrated by different experiments involving donor and acceptor labeled peptides in fixed donor:acceptor and fixed peptide:lipid/detergent ratios, and performing competition experiments on those samples using unlabeled peptides. For example, the stoichiometry of the heterodimeric Class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) chains, MHC-donor and MHC-acceptor TM peptides, was found to be 1:1 by competing with unlabeled MHC TM peptides120.

Similarly, using a series of FRET experiments, Khadria and Senes were able to determine that the bacterial cell division proteins FtsB and FtsL form a 1:1 higher-order oligomer (hetero-tetramer or even higher)14. First, it was demonstrated that FtsB and FtsL interact strongly using donor-labeled FtsB and acceptor labeled FtsL. Then, the stoichiometry of the complex was obtained by monitoring FRET between equimolar donor- and acceptor-labeled FtsB-TM peptides as the relative concentration of an unlabeled FtsL-TM peptide was increased. The fact that direct FRET was observed between labeled FtsB molecules indicated that at least two FtsB monomers were present in the complex. In addition, the sharp saturation of the FRET efficiency observed once the amount of unlabeled FtsL added reached an equimolar FtsL:FtsB stoichiometry, indicated that the complex contains an equal number of FtsB and FtsL TM helices.

Conclusion

This review has emphasized the important role of FRET to study membrane protein interactions, discussing some of the achievements and the challenges associated with it. Over the last 30 years, FRET methods have greatly contributed to progress in understanding structure and interaction of membrane protein and to investigate their biological role. Various research groups have made key contributions to the growth of field by establishing methods and formalisms necessary to measure interaction of TM helices in detergents and lipids, and compute free energies of association. This review has covered these contributions discussing the different combinations of fluorophores and membrane mimetics used, aiming to provide the reader with a comprehensive overview of the state of the art of this field.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by NIH R01GM099752. We thank Samantha Anderson for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- TM

Transmembrane

- SE-AUC

Sedimentation Equilibrium – Analytical Ultracentifugation

- FRET

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer

- AMCA

6-((6-Amino-4-methylcoumarin-3-acetyl)amino) hexanoic acid

- DANS-Cl

5-Dimethylamino-1-naphthalenesulfonyl chloride

- Pyr

Pyrene

- NBD

2-(4-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-7-yl)aminoethyl]trimethylammonium

- FITC

Fluorescein Isothiocyanate

- FAM

Fluorescein amidite

- BODIPY

Boron-dipyrromethene

- EYFP

Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein

- DABS-Cl

4-(Dimethylamino)azobenzene-4-sulfonyl chloride

- TAMRA

5-Carboxytetramethylrhodamine

- DPBS

4-(Diethylamino)phenylazobenzene-4-sulfonyl chloride

- SDS

Sodium Dodecyl sulfate

- OG

Octyl-glucoside

- DOPC

1,2 – Dioleoylphosphatidylcholine

- DDMAB

N-Dodecyl-N,N-(dimethylammonio)butyrate

- DDM

Dodecylmaltoside

- DMPC

Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine

- PFO

Perfluorooctanoate

- DHPC

Dihexanoylphosphatidylcholine

- DLPC

Dilauroylphosphatidylcholine

- DPC

Dodecylphosphocholine

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPG

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol)

- POPS

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- HEK293T

Human Embryonic Kidney 293 cells expressing the SV40 large T antigen

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex

- MLV

Multi-lamellar vesicle

- LUV

Large unilamellar vesicle

- SUV

Small unilamellar vesicle

References

- 1.Wallin E, von Heijne G. Protein Sci Publ Protein Soc. 1998;7(4):1029. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(12):993. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulmschneider MB, Sansom MSP. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2001;1512(1):1. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bill RM, Henderson PJF, Iwata S, Kunji ERS, Michel H, Neutze R, Newstead S, Poolman B, Tate CG, Vogel H. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(4):335. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moraes I, Evans G, Sanchez-Weatherby J, Newstead S, Stewart PDS. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2014;1838(1 Part A):78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White SH. Protein Sci. 2004;13(7):1948. doi: 10.1110/ps.04712004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engelman DM. Nature. 2005;438(7068):578. doi: 10.1038/nature04394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popot JL, Engelman DM. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1990;29(17):4031. doi: 10.1021/bi00469a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelman DM, Chen Y, Chin C-N, Curran AR, Dixon AM, Dupuy AD, Lee AS, Lehnert U, Matthews EE, Reshetnyak YK, Senes A, Popot J-L. FEBS Lett. 2003;555(1):122. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacKenzie KR, Fleming KG. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18(4):412. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher LE, Engelman DM, Sturgis JN. J Mol Biol. 1999;293(3):639. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merzlyakov M, You M, Li E, Hristova K. J Mol Biol. 2006;358(1):1. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.You M, Li E, Wimley WC, Hristova K. Anal Biochem. 2005;340(1):154. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khadria AS, Senes A. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2013;52(43):7542. doi: 10.1021/bi4009837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khadria A, Senes A. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2013;1063:19. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-583-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming KG. J Mol Biol. 2002;323(3):563. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00920-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choma C, Gratkowski H, Lear JD, DeGrado WF. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2000;7(2):161. doi: 10.1038/72440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemmon MA, Flanagan JM, Treutlein HR, Zhang J, Engelman DM. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1992;31(51):12719. doi: 10.1021/bi00166a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rath A, Glibowicka M, Nadeau VG, Chen G, Deber CM. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(6):1760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813167106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cristian L, Lear JD, DeGrado WF. Protein Sci Publ Protein Soc. 2003;12(8):1732. doi: 10.1110/ps.0378603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cristian L, Lear JD, DeGrado WF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(25):14772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536751100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong H, Blois TM, Cao Z, Bowie JU. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(46):19802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010348107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong H, Chang Y-C, Bowie JU. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2013;1063:37. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-583-5_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris SJ, CSüdhof T, Haynes DH. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Biomembr. 1982;693(2):425. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veatch W, Stryer L. J Mol Biol. 1977;113(1):89. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adair BD, Engelman DM. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1994;33(18):5539. doi: 10.1021/bi00184a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raicu V. J Biol Phys. 2007;33(2):109. doi: 10.1007/s10867-007-9046-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li M, Reddy LG, Bennett R, Silva ND, Jones LR, Thomas DD. Biophys J. 1999;76(5):2587. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pap EH, Bastiaens PI, Borst JW, van den Berg PA, van Hoek A, Snoek GT, Wirtz KW, Visser AJ. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1993;32(48):13310. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Almeida RFM, Loura LMS, Fedorov A, Prieto M. J Mol Biol. 2005;346(4):1109. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao M, Mayor S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746(3):221. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Owen DM, Neil MAA, French PMW, Magee AI. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18(5):591. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jares-Erijman EA, Jovin TM. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10(5):409. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luís MS, Loura MP. Front Physiol. 2011;2:82. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rath A, Deber CM. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:135. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senes A, Engel DE, DeGrado WF. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14(4):465. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackenzie KR. Chem Rev. 2006;106(5):1931. doi: 10.1021/cr0404388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacKenzie KR, Fleming KG. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18(4):412. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore DT, Berger BW, DeGrado WF. Structure. 2008;16(7):991. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arkin IT, Brunger AT. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1429(1):113. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hubert P, Sawma P, Duneau J-P, Khao J, Hénin J, Bagnard D, Sturgis J. Cell Adhes Migr. 2010;4(2):313. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.2.12430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wucherpfennig KW, Gagnon E, Call MJ, Huseby ES, Call ME. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(4):a005140. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li E, Hristova K. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2006;45(20):6241. doi: 10.1021/bi060609y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grigoryan G, Moore DT, DeGrado WF. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80(1):211. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-091008-152423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schick S, Chen L, Li E, Lin J, Köper I, Hristova K. Biophys J. 2010;99(6):1810. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolber PK, Hudson BS. Biophys J. 1979;28(2):197. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wimley WC, White SH. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2000;39(1):161. doi: 10.1021/bi991836l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.King C, Sarabipour S, Byrne P, Leahy DJ, Hristova K. Biophys J. 2014;106(6):1309. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fernandes F, Loura LMS, Chichón FJ, Carrascosa JL, Fedorov A, Prieto M. Biophys J. 2008;94(8):3065. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fisher LE, Engelman DM, Sturgis JN. Biophys J. 2003;85(5):3097. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anbazhagan V, Cymer F, Schneider D. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;495(2):159. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anbazhagan V, Schneider D. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2010;1798(10):1899. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stangl M, Unger S, Keller S, Schneider D. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e110970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stangl M, Veerappan A, Kroeger A, Vogel P, Schneider D. Biophys J. 2012;103(12):2455. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stahl PJ, Cruz JC, Li Y, Michael Yu S, Hristova K. Anal Biochem. 2012;424(2):137. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merzlyakov M, Chen L, Hristova K. J Membr Biol. 2007;215(2–3):93. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9009-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li E, Placone J, Merzlyakov M, Hristova K. Anal Chem. 2008;80(15):5976. doi: 10.1021/ac800616u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Merzlyakov M, Li E, Hristova K. Langmuir. 2006;22(3):1247. doi: 10.1021/la051933h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merzlyakov M, Li E, Casas R, Hristova K. Langmuir. 2006;22(16):6986. doi: 10.1021/la061038d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merzlyakov M, Li E, Gitsov I, Hristova K. Langmuir. 2006;22(24):10145. doi: 10.1021/la061976d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merzlyakov M, Li E, Hristova K. Biointerphases. 2008;3(2):FA80. doi: 10.1116/1.2912096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarabipour S, Hristova K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828(8):1829. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen L, Novicky L, Merzlyakov M, Hristov T, Hristova K. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(10):3628. doi: 10.1021/ja910692u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li E, You M, Hristova K. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2005;44(1):352. doi: 10.1021/bi048480k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li E, You M, Hristova K. J Mol Biol. 2006;356(3):600. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.You M, Li E, Hristova K. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2006;45(17):5551. doi: 10.1021/bi060113g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.You M, Spangler J, Li E, Han X, Ghosh P, Hristova K. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2007;46(39):11039. doi: 10.1021/bi700986n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Placone J, Hristova K. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e46678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Placone J, He L, Del Piccolo N, Hristova K. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2014;1838(9):2326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Go MY, Kim S, Partridge AW, Melnyk RA, Rath A, Deber CM, Mogridge J. J Mol Biol. 2006;360(1):145. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Therien AG, Deber CM. J Mol Biol. 2002;322(3):583. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00781-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnson RM, Heslop CL, Deber CM. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2004;43(45):14361. doi: 10.1021/bi0492760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hein C, Henrich E, Orbán E, Dötsch V, Bernhard F. Eng Life Sci. 2014;14(4):365. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seddon AM, Curnow P, Booth PJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666(1–2):105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lyukmanova EN, Shenkarev ZO, Khabibullina NF, Kopeina GS, Shulepko MA, Paramonov AS, Mineev KS, Tikhonov RV, Shingarova LN, Petrovskaya LE, Dolgikh DA, Arseniev AS, Kirpichnikov MP. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2012;1818(3):349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jaud S, Fernández-Vidal M, Nilsson I, Meindl-Beinker NM, Hübner NC, Tobias DJ, Gvon Heijne, White SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(28):11588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900638106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(35):32403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gohon Y, Popot J-L. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;8(1):15. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Le Maire M, Champeil P, Moller JV. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1508(1–2):86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(00)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McQuade DT, Quinn MA, Yu SM, Polans AS, Krebs MP, Gellman SH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39(4):758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu SM, McQuade DT, Quinn MA, Hackenberger CP, Krebs MP, Polans AS, Gellman SH. Protein Sci Publ Protein Soc. 2000;9(12):2518. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tribet C, Audebert R, Popot J-L. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93(26):15047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ujwal R, Bowie JU. Methods San Diego Calif. 2011;55(4):337. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Killian JA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1376(3):401. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.MacKenzie KR, Prestegard JH, Engelman DM. Science. 1997;276(5309):131. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lomize MA, Lomize AL, Pogozheva ID, Mosberg HI. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(5):623. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btk023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]