Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this study was to describe the effect of race on pathologic complete response (pCR) rates and survival outcomes in women with triple receptor–negative (TN) breast cancers.

Patients and Methods

Four hundred seventy-one patients with TN breast cancer diagnosed between 1996 and 2005 and treated with primary systemic chemotherapy were included. pCR was defined as no residual invasive cancer in the breast and axillary lymph nodes. Overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method and compared between groups using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were fitted for each survival outcome to determine the relationship of patient and tumor variables with outcome.

Results

Median follow-up time was 24.5 months. One hundred patients (21.2%) were black, and 371 patients (78.8%) were white/other race. Seventeen percent of black patients (n = 17) and 25.1% of white/other patients (n = 93) achieved a pCR (P = .091). Three-year RFS rates were 68% (95% CI, 56% to 76%) and 62% (95% CI, 57% to 67%) for black and white/other patients, respectively, with no significant difference observed between the two groups (P = .302). Three-year OS was similar for the two racial groups. After controlling for patient and tumor characteristics, race was not significantly associated with RFS (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.08; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.68; P = .747) or OS (HR = 1.08; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.68; P = .735) when white/other patients were compared with black patients.

Conclusion

Race does not significantly affect pCR rates or survival outcomes in women with TN breast cancer treated in a single institution under the same treatment conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Despite increasing incidence of breast cancer seen worldwide,1 overall, developed countries have seen a decrease in the mortality rates associated with this disease primarily because of implementation of screening programs,2 administration of anthracycline/taxane-based systemic chemotherapy regimens, improved local control of early breast cancer,3,4 and more recently, the introduction of trastuzumab into the treatment paradigm of women with HER2/neu–positive tumors.5,6 However, survival disparities exist among women of different racial groups. Age-adjusted breast cancer mortality rates among African American women of 36.4 deaths per 100,000 compared with the significantly lower rate of 28.3 deaths per 100,000 among white women have been reported,7 with several factors implicated including social, economic, and biologic factors.8-14

In an effort to reduce mortality rates further, research has focused on characterizing breast tumor subtypes to define optimal therapeutic strategies that will serve to improve patient survival across racial groups. Gene profiling has identified up to six molecular subtypes of breast carcinomas15 (including luminal, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER-2] positive/estrogen receptor [ER] negative, and basal-like). Although the two hormone receptor–negative subtypes are known to be associated with poorer outcomes,16,17 studies indicate that these are the groups that also benefit the most from adjuvant systemic chemotherapy.18 In addition, several studies have shown that compared with white women, young African American women have a higher incidence of triple receptor–negative (TN) tumors, which comprise approximately 85% of all basal-like tumors, thereby accounting for the biologic factor relating to poor prognosis of African American women afflicted with breast cancer.12,14 However, it is important to note that although there is a high concordance between TN and basal-like tumors, not all TN tumors are basal like.

Primary systemic chemotherapy (PSC) is a standard approach to treating women with locally advanced breast cancers, with higher survival rates reported among patients who attain a pathologic complete response (pCR).19 Studies20,21 have reported a higher sensitivity and pCR rate of hormone receptor–negative tumors to PSC compared with hormone receptor–positive tumors. With 10% to 15% of breast carcinomas known to be of poor prognostic TN type, with a higher incidence observed among African American women, optimization of preoperative chemotherapy to maximize pCR rates would be ideal in this cohort. However, studies reporting the incidence of pCR and related long-term outcomes in women of different racial groups have been limited, making definitive conclusions and recommendations difficult. Thus, the purpose of this retrospective study was to describe the effect of race on pCR rates and survival outcomes among women with TN breast cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

A prospectively maintained database in the Breast Medical Oncology Department of the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (M. D. Anderson) was searched to identify female patients with TN breast cancer who were treated with PSC. To confirm accuracy of information, medical charts of all patients were reviewed. Patients excluded included those who had metastatic disease at diagnosis, who had bilateral disease or more than one primary tumor, whose tumors expressed ER and/or progesterone receptor (PR), who had overexpression and/or gene amplification of HER2/neu, who did not undergo definitive surgery, or whose pathologic response in both the breast and axilla could not be assessed. Variables recorded included patient demographics, race, tumor characteristics, initial clinical stage, surgical details, pathologic stage, presence of residual disease after PSC, and recurrence information. Race information was self-reported based on data derived from survey forms completed at first patient visit to the institution. The Institutional Review Board at M. D. Anderson approved this study. The final analyses included 471 patients with TN breast cancer diagnosed between 1996 and 2005.

Staging and Pathology

Initial clinical stage and final pathologic stage of all patients were defined according to the staging criteria proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer Criteria (sixth edition)22 in 2003. All pathologic specimens were reviewed by dedicated breast pathologists at M. D. Anderson. Invasive carcinoma was confirmed on initial core biopsy specimens. Histologic type and grade were defined according to the WHO classification system23 and modified Black's nuclear grading system,24 respectively. All surgical breast and axillary lymph node specimens were reviewed to identify the presence or absence of residual invasive and in situ disease. pCR was defined as the absence of residual invasive disease in both the breast and axillary lymph nodes.

For determination of hormone receptor status, immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis was performed using monoclonal antibodies 6f11 (Novacastra Laboratories Ltd, Burlingame, CA) and 1A6 (Novocastra Laboratories) for ER and PR, respectively. Negative ER and PR status was defined as nuclear staining of less than 5%. HER2/neu-negative status was defined as either 1+ or no staining by IHC and/or absence of gene amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Path Vysion HER2/neu DNA probe kit (Vysis, Downers Grove, IL) and the monoclonal antibody AB8 (Neomarker/Labvision Corporation, Fremont, CA) were used for HER2/neu fluorescence in situ hybridization and IHC analysis, respectively.

Treatment

All patients were treated with a multidisciplinary approach. Overall, 98% of patients received an anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimen. Fifty-two patients (11.05%) received an anthracycline-based regimen without a taxane, 410 patients (87.04%) received a taxane/anthracycline-based combination, eight patients (1.70%) received single-agent taxane without an anthracycline, and one patient (0.21%) received a nonanthracycline/nontaxane-based regimen. Anthracycline-based regimens included three to six cycles of one of the following regimens: fluorouracil 500 mg/m2, epirubicin 100 mg/m2, and cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) on day 1, every 3 weeks; fluorouracil 500 mg/m2 IV on days 1 and 4, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 IV by continuous infusion over 72 hours, and cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 IV on day 1, every 3 weeks; or doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 600 m/m2 IV on day 1, every 3 weeks. Taxanes administered included paclitaxel 175 to 250 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 21 days for four cycles, paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 IV on day 1 once a week for 12 weeks, or docetaxel 100 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3 weeks for four cycles.

After PSC, all patients underwent definitive surgery. The decision for or against breast-conserving surgery (BCS) was based on a combination of recommendations made by the multidisciplinary treating team and patient preference. The approach to BCS after PSC has been previously described.25 Two hundred sixty-nine patients (57.5%) underwent total mastectomy, and 199 patients (42.5%) underwent BCS. Of note, three patients had no clinical or radiologic evidence of disease in the breast at presentation but had prominent lymphadenopathy and, thus, did not undergo any form of breast surgery and were considered to have no disease in the breast. Four hundred sixty-eight patients had axillary lymph node surgery, of whom 376 (80.34%) had axillary lymph node dissection and 90 (19.23%) had sentinel lymph node biopsy; for two patients (0.43%), the method of axillary surgery could not be determined. Three patients did not have axillary lymph node surgery because of patient preference. Patients received local radiation therapy preoperatively if no response to PSC was observed. Postoperative radiation therapy was administered if patients had BCS, locally advanced disease (including T3 tumor) at presentation, or four or more involved axillary lymph nodes after completion of PSC. Overall, 383 patients (81.3%) received local radiation therapy, whereas 88 patients (18.7%) did not. None of the patients received hormonal therapy.

Statistical Analysis and Outcome Measures

Race variable was divided into the following two groups: black patients and white/other race patients. Similarly, clinical stage was divided into two groups, as follows: clinical stage I to IIIA, representing patients whose tumors were operable at presentation; and clinical stage IIIB and IIIC, representing patients whose tumors were not operable at presentation. Because of the small number of patients with grade 1 tumors, patients with grade 1 or 2 tumors were grouped together.

Patient and tumor characteristics were tabulated by pCR and race and compared across groups with the χ2 test or Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate. Median follow-up time was calculated as the median observation time among all patients. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of definitive surgery to the date of death from any cause or date of last follow-up. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was measured from the date of definitive surgery to the date of first recurrence (local or distant) or date of last follow-up. Patients who died before experiencing a disease recurrence were considered censored at their date of death in the analyses of RFS. Survival outcomes were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method and compared between groups using the log-rank statistic. We fitted Cox proportional hazards models for each survival outcome to determine the simultaneous relationship of patient and tumor variables with each outcome. For each outcome, pCR, clinical stage, lymphovascular invasion, and surgery type achieved statistical significance by the likelihood ratio test and were included in the Cox model. Pathologic stage was not considered for inclusion because the term was collinear with pCR. The race variable was included because our primary objective was to look at survival differences between the black and white/other groups. The final model included the following six dichotomous variables: race, pCR (yes v no), initial clinical stage (I to IIIA v IIIB/IIIC), menopausal status (postmenopausal v premenopausal), lymphovascular invasion (yes v no), and surgery (total mastectomy v segmental mastectomy). P < .05 was considered statistically significant, and P value was two sided for all analyses performed. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

One hundred patients (21.2%) were black, and 371 patients (78.8%) were white/other race (Table 1). Median age at diagnosis was 47 years (range, 22 to 75 years) among black patients and 48 years (range, 25 to 78 years) among white/other patients. Predominant histologic type was invasive ductal carcinoma (93%) in both racial groups. The majority of patients (91.7%) had grade 3 disease, and this percentage was similar in the two racial groups. Thirty-eight percent of black patients (n = 38) and 28.3% of white/other patients (n = 105) had clinical stage IIIB or IIIC disease. Median number of pre- and postoperative chemotherapy cycles was similar between the two racial groups. Eighty-five percent of black patients (n = 85) and 84.6% of white/other patients (n = 314) received anthracyclines and taxanes as part of their treatment regimen. Seventeen percent of black patients (n = 17) and 25.1% of white/other patients (n = 93) achieved a pCR (P = .091).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Race

| Characteristic | Black (n = 100) |

White and Other Race (n = 371) |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | ||||

| Age, years | .935 | ||||||

| Minimum | 22 | 25 | |||||

| Median | 47 | 48 | |||||

| Maximum | 75 | 78 | |||||

| Menopausal status | .276 | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 43 | 43.4 | 184 | 49.6 | |||

| Postmenopausal | 56 | 56.6 | 187 | 50.4 | |||

| Histology | .969 | ||||||

| Other | 7 | 7.0 | 25 | 6.9 | |||

| Ductal | 93 | 93.0 | 338 | 93.1 | |||

| Clinical stage | .061 | ||||||

| IIIB/IIIC | 38 | 38.0 | 105 | 28.3 | |||

| I-IIIA | 62 | 62.0 | 266 | 71.7 | |||

| pCR | .091 | ||||||

| No | 83 | 83.0 | 278 | 74.9 | |||

| Yes | 17 | 17.0 | 93 | 25.1 | |||

| Grade | .382 | ||||||

| 1/2 | 6 | 6.1 | 32 | 8.9 | |||

| 3 | 92 | 93.9 | 329 | 91.1 | |||

| No. of nodes removed | .467 | ||||||

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Median | 14 | 15 | |||||

| Maximum | 45 | 59 | |||||

| LVI | .179 | ||||||

| Negative | 76 | 78.4 | 264 | 71.5 | |||

| Positive | 21 | 21.6 | 105 | 28.5 | |||

| Surgery | .506 | ||||||

| Mastectomy | 54 | 54.5 | 215 | 58.3 | |||

| Segmental | 45 | 45.5 | 154 | 41.7 | |||

| Chemotherapy | .341 | ||||||

| A alone | 8 | 8.0 | 43 | 11.6 | |||

| A + T | 85 | 85.0 | 314 | 84.6 | |||

| T alone | 7 | 7.0 | 13 | 3.5 | |||

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |||

| XRT | .176 | ||||||

| No | 14 | 14.0 | 74 | 19.9 | |||

| Yes | 86 | 86.0 | 297 | 80.1 | |||

Abbreviations: pCR, pathologic complete response; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; A, anthracycline; T, taxane; XRT, radiotherapy.

Survival Outcomes

Median follow-up time of all patients was 24.5 months (range, 0.3 to 117.0 months). Median follow-up time was similar between the two pCR and racial groups. Twenty-nine black patients (29%) and 131 white/other patients (32.9%) experienced a recurrence. Three-year RFS rates were 68% (95% CI, 56% to 76%) and 62% (95% CI, 57% to 67%) for black and white/other patients, respectively (P = .302; Table 2). Among black and white/other patients, 17 (17%) and 99 (26.7%) patients have died, respectively. Three-year OS rate was similar for the two racial groups (OS = 71%, P = .919).

Table 2.

Kaplan-Meier Estimates for 3-Year Relapse-Free and Overall Survival

| Factor | No. of Patients | Relapse-Free Survival |

Overall Survival |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Events | 3-Year Estimate (%) | 95% CI (%) | P | No. of Events | 3-Year Estimate (%) | 95% CI (%) | P | ||||||||

| All | 471 | 160 | 63 | 58 to 68 | 125 | 71 | 66 to 76 | ||||||||

| Age, years | .015 | .441 | |||||||||||||

| < 50 | 260 | 101 | 58 | 51 to 64 | 73 | 69 | 61 to 75 | ||||||||

| ≥ 50 | 211 | 59 | 70 | 62 to 76 | 52 | 74 | 66 to 80 | ||||||||

| Menopause status | .0009 | .081 | |||||||||||||

| Premenopausal | 227 | 94 | 56 | 48 to 62 | 68 | 66 | 58 to 73 | ||||||||

| Postmenopausal | 243 | 66 | 71 | 64 to 76 | 57 | 75 | 69 to 81 | ||||||||

| Grade | .098 | .199 | |||||||||||||

| 1/2 | 38 | 9 | 74 | 54 to 86 | 8 | 84 | 65 to 93 | ||||||||

| 3 | 421 | 146 | 63 | 57 to 68 | 112 | 70 | 65 to 75 | ||||||||

| No. of nodes removed | .023 | .108 | |||||||||||||

| < 10 | 136 | 34 | 74 | 65 to 81 | 26 | 78 | 69 to 85 | ||||||||

| ≥ 10 | 324 | 120 | 60 | 54 to 65 | 92 | 70 | 63 to 75 | ||||||||

| LVI | < .0001 | < .0001 | |||||||||||||

| No | 340 | 86 | 73 | 67 to 78 | 70 | 77 | 71 to 82 | ||||||||

| Yes | 126 | 71 | 40 | 31 to 49 | 53 | 56 | 46 to 66 | ||||||||

| Surgery | < .0001 | < .0001 | |||||||||||||

| Mastectomy | 269 | 127 | 49 | 43 to 56 | 96 | 60 | 53 to 67 | ||||||||

| Segmental | 199 | 31 | 83 | 76 to 88 | 28 | 85 | 78 to 90 | ||||||||

| pCR | < .0001 | < .0001 | |||||||||||||

| No | 361 | 150 | 55 | 49 to 61 | 121 | 63 | 57 to 69 | ||||||||

| Yes | 110 | 10 | 91 | 83 to 95 | 4 | 97 | 91 to 99 | ||||||||

| Race | .302 | .919 | |||||||||||||

| Black | 100 | 29 | 68 | 56 to 76 | 26 | 71 | 60 to 80 | ||||||||

| White/other | 371 | 131 | 62 | 57 to 67 | 99 | 71 | 65 to 76 | ||||||||

| Race (no pCR) | .214 | .611 | |||||||||||||

| Black | 83 | 29 | 61 | 49 to 71 | 26 | 65 | 53 to 76 | ||||||||

| White/other | 278 | 121 | 53 | 47 to 59 | 95 | 63 | 55 to 69 | ||||||||

| Race (pCR) | .71 | — | |||||||||||||

| Black | 17 | 0 | 100 | — | 0 | 100 | — | ||||||||

| White/other | 93 | 10 | 89 | 80 to 94 | 4 | 97 | 90 to 99 | ||||||||

| Clinical stage | < .0001 | < .0001 | |||||||||||||

| I | 16 | 1 | 92 | 57 to 99 | 2 | 100 | — | ||||||||

| II | 245 | 63 | 72 | 66 to 78 | 49 | 79 | 72 to 85 | ||||||||

| IIIA | 67 | 24 | 63 | 49 to 73 | 20 | 68 | 54 to 78 | ||||||||

| IIIB | 89 | 43 | 47 | 35 to 58 | 40 | 49 | 37 to 60 | ||||||||

| IIIC | 54 | 29 | 43 | 28 to 58 | 14 | 63 | 40 to 79 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: LVI, lymphovascular invasion; pCR, pathologic complete response.

Survival Outcomes for pCR Subgroup

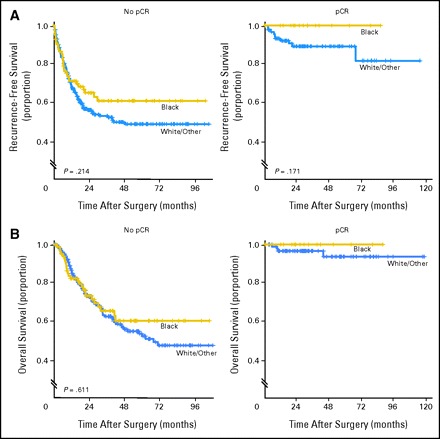

In the subgroup with pCR, the 3-year RFS and OS rates were 100% for black patients. Among white/other patients who achieved a pCR, 3-year RFS and OS rates were 89% (95% CI, 80% to 94%) and 97% (95% CI, 90% to 99%), respectively. No significant difference was observed among the survival outcomes of the two racial groups (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots of (A) recurrence-free survival and (B) overall survival by race and pathologic complete response (pCR).

Survival Outcomes for Non-pCR Subgroup

Among black patients in the subgroup who did not achieve a pCR, the RFS and OS rates were 61% (95% CI, 49% to 71%) and 65% (95% CI, 53% to 76%), respectively. Among white/other patients who did not achieve a pCR, the RFS and OS rates were 53% (95% CI, 47% to 59%) and 63% (95% CI, 55% to 69%), respectively. No significant difference was observed among the two racial groups for each of the survival outcomes (Fig 1).

Multivariable Model Results

After controlling for patient and tumor characteristics, race was not significantly associated with RFS (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.08; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.68; P = .747) and OS (HR = 1.08; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.68; P = .735) when white/other patients were compared with black patients (Table 3). Patients who achieved a pCR had an improved RFS (HR = 0.12; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.32; P < .0001) and decreased hazard of death (HR = 0.13; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.84; P = .004) compared with patients who did not achieve a pCR.

Table 3.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model Results

| Variable | Overall Survival |

Recurrence-Free Survival |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |||||

| Race: white/other v black | 1.08 | 0.69 to 1.68 | .735 | 1.08 | 0.69 to 1.68 | .747 | ||||

| pCR: yes v no | 0.13 | 0.05 to 0.34 | < .0001 | 0.12 | 0.04 to 0.32 | < .0001 | ||||

| Clinical stage: I-IIIA v IIIB/IIIC | 0.58 | 0.40 to 0.84 | .004 | 0.59 | 0.41 to 0.86 | .005 | ||||

| Menopausal status: postmenopausal v premenopausal | 0.83 | 0.58 to 1.18 | .296 | 0.80 | 0.56 to 1.14 | .214 | ||||

| LVI: yes v no | 1.57 | 1.08 to 2.27 | .017 | 1.74 | 1.20 to 2.52 | .004 | ||||

| Surgery: mastectomy v segmental | 2.24 | 1.44 to 3.47 | .0003 | 2.34 | 1.51 to 3.63 | .0001 | ||||

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; pCR, pathologic complete response; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to describe the effect of race on pCR rates and survival outcomes in women with TN breast cancers. In this single-institution study, using a large cohort of women with TN disease treated with PSC that was predominantly anthracycline based, we show that pCR rates and survival outcomes were similar between black and white/other race patients. Furthermore, our results show that regardless of race, achieving a pCR led to improved survival outcomes compared with patients with persistent residual disease after treatment with PSC.

Several studies have documented that black women have a lower incidence of breast cancer associated with higher mortality compared with white women.26-29 Contributing factors are multifactorial, including socioeconomic factors, access to health insurance and medical coverage, differences in treatment, higher stage of disease at diagnosis, and biologic differences in the diagnosed breast tumor.8-11 Biologic differences noted among black women with breast cancer are a higher prevalence of tumors that are hormone receptor negative and of high grade.12-14,30 Carey et al13 observed that, compared with patients with luminal A breast tumors, patients who had basal-like tumors were 2.1 times more likely to be of African American race (P = .004), with survival being significantly shorter among patients with either basal-like or HER-2–positive/ER-negative tumors. Bauer et al14 observed that women with TN tumors were more likely to be non-Hispanic black (odds ratio = 1.77), and non-Hispanic black women with late-stage TN disease had a significantly worse survival compared with non-Hispanic white women with TN disease (5-year relative survival, 14% for non-Hispanic black women v 36% for non-Hispanic white women). Dean-Colomb et al31 looked at the transcriptional profiles of tumors of 98 women with TN disease who had received PSC. The authors noted that in addition to no differences observed in pCR rates by ethnicity, no genes were differentially expressed among African American women compared with other women. This provides further evidence that biologic differences that have contributed to survival disparities observed among African American women are primarily a result of frequency of bad prognostic subgroups rather than differences at the molecular level.

In a recent study of more than 6,000 women from M. D. Anderson, Shen et al30 reported African American women, compared with white women, to have a lower incidence of both ER-positive disease (53% v 65%, respectively; P < .001) and PR-positive disease (45% v 54%, respectively; P < .0001). The study further noted two important observations. First, shorter survival rates among African American women compared with white women and among women who had hormone receptor–negative disease compared with those who had hormone receptor-positive disease were observed. Second, no significant differences in primary treatment of breast cancer were observed among the different racial groups. In another report, Woodward et al32 explored the effect of race on survival outcome in patients treated at M. D. Anderson on prospective clinical trials where all patients received anthracycline-based chemotherapy. The study reported that despite uniform distribution of treatment, African American race was independently associated with poorer survival. The results of both studies indicate that even after controlling for treatment distribution, biologic differences play a major contributing role to the poor survival observed among black patients with breast cancer.

The cohort we chose to study is unique for several reasons. First, the majority of patients were treated at M. D. Anderson, and our results indicate that the treatments received by the two racial groups studied were similar. This reduced bias from differential treatment distribution often observed in other studies. Second, we selected a group of women who were all treated with standard preoperative chemotherapy, the majority of which was anthracycline based. This is important because evidence from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group3 indicates that a significant survival advantage is associated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy administered to women with early-stage breast cancer, and it allowed us the opportunity to look at the effect of race on chemotherapy sensitivity. Third, by selecting a group of women who all had TN disease, we were able to look at the effect of race on a group of women who all had a poor prognostic subtype of breast cancer.

The results of our study indicated no significant differences in either RFS or OS between black and white/other patients even after controlling for patient and tumor characteristics. Furthermore, no significant differences in survival outcomes were observed between the two racial groups when subdivided according to pCR. As is observed in many retrospective studies, we acknowledge that limited power may have accounted for the nonsignificant differences in survival outcomes. However, despite this limitation, several important hypothesis-generating trends were observed. First, we noted that although black women with TN tumors historically have been shown to have poor outcomes,12-14 in our cohort among patients who had achieved a pCR, survival outcomes were comparable to those observed for the whole cohort, with survival estimates approaching 100% at 3 years. This suggests that among black women, pCR also serves as an important surrogate marker of improved long-term outcome. Second, we noted small absolute differences in 3-year RFS, ranging from 8% to 11%, between the two racial groups in both patients who had achieved pCR and those who had residual disease that consistently favored black patients compared with white/other patients. This trend was further observed in the Cox proportional hazards model, where a nonsignificant trend for worse survival was observed among white/other women compared with black women. This challenges the current thinking that black patients with breast cancer do poorly overall. We hypothesize that when similar treatment and follow-up are delivered within a specialized cancer institution to women with TN disease, survival among black and white/other patients is similar. These observations need to be confirmed in a larger prospective study.

In conclusion, this study, to our knowledge, is one of the largest cohorts to study the effects of race on pCR rates and survival in patients with TN disease. Our study makes the important observation that race did not significantly affect pCR rates or survival outcomes in women with TN disease. In addition, the prognostic impact of pCR was similar between the two racial groups. Although the observations and hypothesis generated from the results of this study are subject to the limitations seen in any retrospective study, our study is unique in that all patients, regardless of race, received similar treatment and follow-up, a factor not seen in many similar studies. However, the conclusions drawn are important and need to be verified in a larger prospective study.

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Shaheenah Dawood, Ana Maria Gonzalez-Angulo

Administrative support: Shu-Wan Kau

Collection and assembly of data: Shaheenah Dawood, Shu-Wan Kau

Data analysis and interpretation: Shaheenah Dawood, Kristine Broglio

Manuscript writing: Shaheenah Dawood, Marjorie C. Green, Sharon H. Giordano, Funda Meric-Bernstam, Thomas A. Buchholz, Constance Albarracin, Wei T. Yang, Bryan T.J. Hennessy, Gabriel N. Hortobagyi, Ana Maria Gonzalez-Angulo

Final approval of manuscript: Shaheenah Dawood, Kristine Broglio, Shu-Wan Kau, Marjorie C. Green, Sharon H. Giordano, Funda Meric-Bernstam, Thomas A. Buchholz, Constance Albarracin, Wei T. Yang, Bryan T.J. Hennessy, Gabriel N. Hortobagyi, Ana Maria Gonzalez-Angulo

Footnotes

published online ahead of print at www.jco.org on December 1, 2008

Supported in part by the Susan G. Komen Foundation and the Nellie B. Connally Fund for Breast Cancer Research; also supported by Grant No. K23CA121994-01 (A.M.G.-A.) from the National Cancer Institute and an American Society of Clinical Oncology Career Development Award (A.M.G.-A.).

Presented in part at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008 Breast Cancer Symposium, September 5-7, 2008, Washington, DC.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF: Patterns of cancer incidence mortality, and prevalence across five continents: Defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol 24:2137-2150, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al: Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353:1784-1792, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group: Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 365:1687-1717, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Overgaard M, Jensen MB, Overgaard J, et al: Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk postmenopausal breast-cancer patients given adjuvant tamoxifen: Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group DBCG 82c randomised trial. Lancet 353:1641-1648, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, et al: Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353:1659-1672, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al: Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353:1673-1684, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program SEER*Stat Database: Mortality-all COD, public-use with state, total U.S for expanded races/Hispanics (1990-2001). http://www.seer.cancer.gov

- 8.Bradley CJ, Given XW, Roberts C: Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. J Natl Cancer Inst 94:490-496, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayanian JZ, Kohler BA, Abe T, et al: The relation between health insurance coverage and clinical outcomes among women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med 329:326-331, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McWhorter WP, Mayer WJ: Black/white differences in type of initial breast cancer treatment and implications for survival. Am J Public Health 77:1515-1517, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furberg H, Millikan R, Dressler L, et al: Tumor characteristics in African American and white women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 68:33-43, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ihemelandu CU, Lefall LD, Dewitty RL, et al: Molecular breast cancer subtypes in premenopausal and postmenopausal African-American women: Age-specific prevalence and survival. J Surg Res 143:109-118, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al: Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA 295:2492-2502, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, et al: Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype. Cancer 109:1721-1728, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al: Molecular portraits of human breast tumors. Nature 406:747-752, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, et al: Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:10869-10874, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, et al: Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:8418-8423, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry D, Cirrinicione C, Henderson IC, et al: Estrogen receptor status and outcomes of modern chemotherapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer. JAMA 295:1658-1667, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuerer HM, Newman LA, Smith TL, et al: Clinical course of breast cancer patients with complete pathological primary tumor and axillary lymph node response to doxorubicin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 17:460-469, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouzier R, Perou CM, Symmans WF, et al: Breast cancer molecular subtypes respond differently to pre operative chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 11:5678-5685, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carey LA, Dees C, Sawyer L, et al: The triple negative paradox: Primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin Cancer Res 13:2329-2334, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singletary SE, Allred C, Ashley P, et al: Staging system for breast cancer: Revisions for the 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Surg Clin North Am 83:803-819, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The World Health Organization: The World Health Organization Histological Typing of Breast Tumors—Second Edition. Am J Clin Pathol 78:806-816, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black MM, Speer FD: Nuclear structure in cancer tissues. Surg Gynecol Obstet 105:97-102, 1957 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen AM, Meric-Bernstam F, Hunt KK: Breast conservation after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: The MD Anderson cancer center experience. J Clin Oncol 22:2303-2312, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campleman S, Curtis R: Demographic aspects of breast cancer incidence and mortality in California, 1988-1999, in Morris C, Kwong SL (eds): Breast Cancer in California, 2003. Sacramento, CA, California Department of Health Services, Cancer Surveillance Section, 2004

- 27.Chu KC, Lamar CA, Freeman HP: Racial disparities in breast carcinoma survival rates: Separating factors that affect diagnosis from factors that affect treatment. Cancer 97:2853-2860, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chlebowski RT, Chen Z, Anderson GL, et al: Ethnicity and breast cancer: Factors influencing differences in incidence and outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:439-448, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ries L, Eisner M, Kosary M: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2000. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute, 2003

- 30.Shen Y, Dong W, Esteva FJ, et al: Are there racial differences in breast cancer treatments and clinical outcome for women treated at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center? Breast Cancer Res Treat 102:347-356, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dean-Colomb W, Yan K, Liedtke C, et al: Transcriptional profiles of triple receptor-negative breast cancer: Are Caucasian, Hispanic, and African-American women different? J Clin Oncol 26:750s, 2008. (suppl, abstr 22014) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodward WA, Huang EH, McNeese MD, et al: African-American race is associate with a poorer overall survival rate for breast cancer patients treated with mastectomy and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy. Cancer 107:2662-2668, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]