Abstract

Background

Prevalence of high blood pressure (BP) among American children has increased over the past two decades, due in part to increasing rates of obesity and excessive dietary salt intake.

Objective

We tested the hypotheses that the relationships among BP, salty taste sensitivity, and salt intake differ between normal-weight and overweight/obese children.

Design

In an observational study, sodium chloride (NaCl) and monosodium glutamate (MSG) taste detection thresholds were measured using the Monell two-alternative, forced-choice, paired-comparison tracking method. Weight and BP were measured, and salt intake was determined by 24-hour dietary recall.

Participants/Setting

Eight- to 14-year-olds (N=97; 52% overweight or obese) from the Philadelphia area completed anthropometrics and BP measurements; 97% completed one or both thresholds. Seventy-six percent provided valid dietary recall data. Testing was completed between December 2011 and August 2012.

Main outcome measures

NaCl and MSG detection thresholds, BP, and dietary salt intake.

Statistical analyses

Outcome measures were compared between normal-weight and overweight/obese children with t-tests. Relationships among outcome measures within groups were examined with Pearson correlations, and multiple regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between BP and thresholds, controlling for age, BMI-Z score, and dietary salt intake.

Results

Salt and MSG thresholds were positively correlated (r(71)=0.30, p=0.01) and did not differ between body-weight groups (p>0.20). Controlling for age, BMI-Z score, and salt intake, systolic BP was associated with NaCl thresholds among normal-weight children (p=0.01), but not among overweight/obese children. All children consumed excess salt (>8 g/day). Grain and meat products were the primary source of dietary sodium.

Conclusions

The apparent disruption in the relationship between salty taste response and BP among overweight/obese children suggests the relationship may be influenced by body weight. Further research is warranted to explore this relationship as a potential measure to prevent development of hypertension.

Keywords: Salty taste, blood pressure, obesity, children, taste sensitivity

Introduction

Characterizing an association between taste perception and blood pressure is an ongoing area of research, based on the premise that taste function may be reflective of physiological processes elsewhere in the body, and as such, serve as a marker for an individual’s health status1. Because of the well-established link between high dietary salt intake and blood pressure2, salty taste has long been an area of focus in examining differences between hypertensives and normotensives in terms of hedonic appeal of salt3–5, perceived salty taste intensity6,7, and sensitivity to salty taste5,8–14, as any differences between these groups may allow for diagnosing or managing hypertension7,15. To date, findings from research of this nature have been largely equivocal.

No definitive association between blood pressure and either salt preference3–5 or perceived salty taste intensity6,7 has been published thus far. Examinations of the link between blood pressure and salty taste sensitivity, measured via detection thresholds (defined as the lowest concentration of a stimulus needed by a subject to detect its presence relative to water16) or recognition thresholds (defined as the lowest concentration of a stimulus correctly identified by name by a subject based on its characteristic taste16), have produced mixed results. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was positively correlated with salty taste recognition thresholds among normal- and underweight 10- to 17-year-old Nigerian children9, and was positively correlated with salty taste detection thresholds among normal-weight but not obese Spanish children (age was not reported)8. No relationship between blood pressure and salty taste detection thresholds was found among 11- to 16-year-old American children who ranged from normal weight to obese3. Among adults, hypertensives had higher recognition thresholds than normotensives in several studies6,10–12, and in one study had higher detection thresholds13. Others found no difference in detection thresholds between adults with and without hypertension11, and in two studies, found no difference in either detection or recognition thresholds between these groups5,14.

Our understanding of potential shared mechanisms underlying salty taste sensitivity and blood pressure thus far may be limited by several confounding factors across studies including differences in subject age, body weight, and dietary salt intake; as well as wide variation in methodologies used to measure taste sensitivity. In light of 1) an increased prevalence of high blood pressure among pediatric populations over the last two decades17,18, and 2) a known association between weight, dietary salt intake, and blood pressure18,19, we examined the relationship between blood pressure and salty taste detection thresholds among normal-weight versus overweight and obese children using a rigorous validated methodology20, and we explored whether differences in dietary salt intake influenced this relationship. To determine whether findings were specific to salty taste sensitivity, detection thresholds were also measured for monosodium glutamate (MSG), because of demonstrated differences in MSG taste sensitivity between obese and nonobese women21, and because MSG is also a sodium-containing taste stimulus. If blood pressure and salty taste sensitivity share a common link, taste measures could provide new insight into our current understanding of the development of high blood pressure in children.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Mothers of 8- to 14-year old healthy children were recruited for a “taste study” from local advertisements in the Philadelphia area and from a list of past subjects who asked to be notified of future studies at the Monell Chemical Senses Center. Children with allergies were excluded from participation. All procedures were approved by the Office of Regulatory Affairs at the University of Pennsylvania. Written informed consent was obtained from each mother, and written informed assent from each child.

Procedures

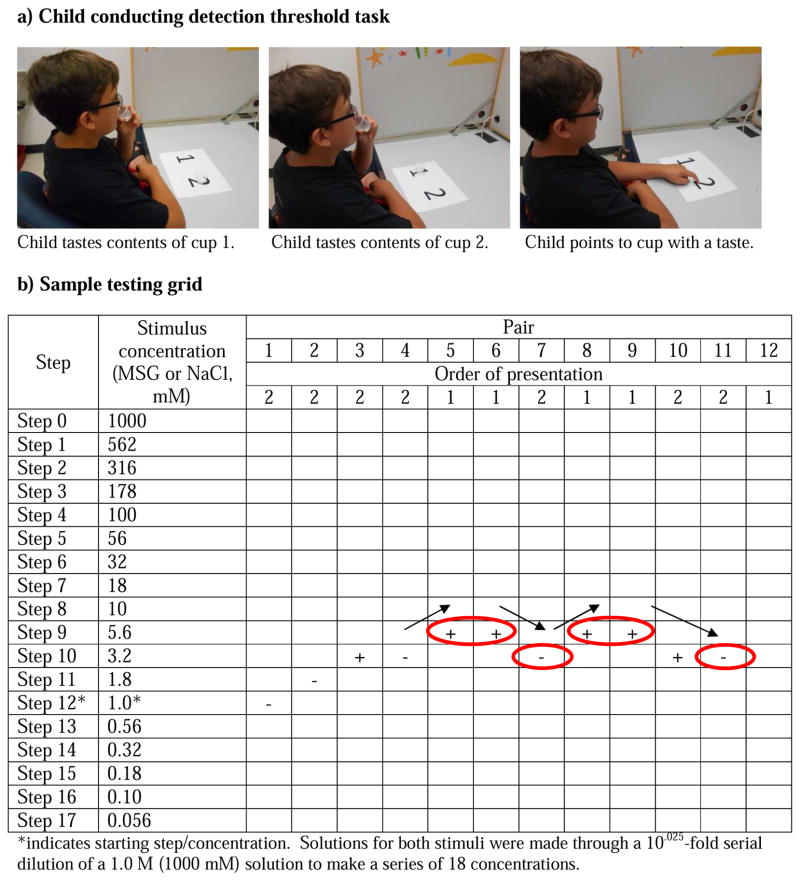

Testing took place in a private, comfortable room specifically designed for sensory testing that was illuminated with red light to mask any visual differences among samples. Subjects consumed no food or drink other than water for at least one hour before the task and acclimated to the testing room and to the researcher for approximately 15 minutes. Prior to testing, all children were trained to become familiar with the method and to assess whether they understood the detection threshold task (modified from pediatric assessment of sucrose preference) 20. Children were presented with a pair of plastic medicine cups: one containing distilled water and the other containing either 0.056 mM or 0.018 M sucrose solution. Children were asked to taste both solutions in the order presented and to point to the solution that had a taste (Figure 1a). This method eliminated the need for a verbal response and is effective for assessing both taste and olfaction in children. The two pairs (water vs. 0.056 mM and water vs. 0.018 M sucrose) provided the children with the experience of tasting a pair of solutions in which they could not detect a difference and a pair in which the difference between solutions was easily discernible, both of which are conditions encountered during threshold testing. Training was repeated with children who did not understand the task after one training session.

Figure 1.

a) A 10-year-old subject performing the paired-comparison threshold tracking method. b) Tracking grid used to determine detection. For order of presentation of pairs, 1 signifies water and 2 signifies the tastant solution (either MSG or NaCl) is presented first within that particular pair. Whether a subject correctly (+) or incorrectly (−) identified the solution with a taste was recorded. Testing continued until four reversals in performance were achieved (circles with arrows). (Parental consent was provided for use of the photograph.)

Taste Detection Thresholds

Detection thresholds for NaCl and MSG in solution were measured separately and in randomized order via a two-alternative forced choice staircase procedure developed at the Monell Center and later adapted for use among pediatric populations 20. As shown in Figure 1b, solutions used for testing ranged in concentration from 0.056 mM to 1 M for both NaCl and MSG. Solutions for both stimuli were made through a 10.025-fold serial dilution of a 1.0 M solution to make a series of 18 concentrations. Solutions were randomized for order across subjects 22. For the first trial and each subsequent trial, subjects were presented with pairs of solutions; within each pair, one solution was distilled water and the other the taste stimulus. Subjects were instructed to taste the first solution presented within a pair, swish the solution in their mouth for 5 seconds, and expectorate. Subjects tasted the second solution within a pair using the same protocol, rinsing their mouth with water once between solutions within a pair and twice between successive pairs. After tasting both solutions within a pair, subjects were asked to point to the solution that had a taste, as in the training task. The concentration of the tastant in the solution presented in the subsequent pair was increased after a single incorrect response and decreased after two consecutive correct responses. A reversal occurred when the concentration sequence changed direction (i.e., an incorrect response followed by a correct response or vice versa). A tracking grid (Figure 1b) was used to record subjects’ responses. The testing procedure was terminated after four reversals occurred, provided the following criteria were met, to ensure a stable measure of the detection threshold: (1) there were no more than two dilution steps between two consecutive reversals, and (2) the reversals did not form an ascending pattern such that positive and negative reversals were achieved at successively higher concentrations23. A subject’s threshold for a tastant was calculated as the mean of the log values of the last four reversals. Threshold testing for each child always began at step 12 (Figure 1b), a stimulus concentration that ensured an adequate number of steps on either side of the starting point to determine an accurate threshold. Though only a narrow section of the testing grid was required to test the subject illustrated in Figure 1b, some children tasted stimuli over a wider range of concentrations before their threshold was determined.

Anthropometry, Biometrics, and Blood Pressure

Children were weighed (kilograms; model 439 physical scale; Detecto Scale Company) and measured for height (centimeters) wearing light clothing and no shoes. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was determined, and age- and sex-specific BMI z-scores were calculated using EpiInfo 3.5 (www.cdc.gov/epiinfo). Participants were placed into one of four BMI categories according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pediatric growth charts 24. None of the children were underweight. For analyses, participants were categorized as either overweight/obese or normal weight. Total body water, fat-free mass, and body fat were estimated by bioelectrical impedance analysis using the Quantum X instrument (RJL Systems)25,26, and waist-to-hip ratio was determined using measurements for abdominal and hip circumferences27. Blood pressure was measured using an appropriately sized automated cuff based on arm circumference (Dinamap, GE Medical Systems) while children were seated with feet flat on the floor. Values were recorded for SBP and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) twice and recorded as the average of the two measurements for each reading. Children were required to rest for 1 minute before and between measurements. Blood pressure category was determined according to the National High Blood Pressure Education Program guidelines for classifying hypertension among children and adolescents 28. Those with normal blood pressure had SBP or DBP below the 90th percentile; those with prehypertension had SBP or DBP between the 90th and 95th percentile or blood pressure that exceeded 120/80 mm Hg; and those with hypertension had SBP or DBP greater than the 95th percentile.

Demographics and Dietary Habits

Demographic data were collected by interview, and dietary intake data were collected and analyzed using the Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Recall system (ASA24), a web-based validated methodology developed by the National Cancer Institute29 that allows for calorie, nutrient, and food group estimates of overall intake. On each testing day, mothers and children sat side by side as the mother reported 24-hour dietary recall for her child to a researcher familiar with ASA24, who entered data into the program on their behalf. Children were asked to report on snacks or foods eaten outside the home (e.g., school)30. After a subject reports a specific food or beverage, ASA24 provides visual depiction of the item in an appropriate dish, which allows subjects to accurately estimate portion sizes. From the data collected, we focused specifically on reported daily sodium intake (mg Na/day) and caloric intake (kcal/day).

To determine the sources of sodium in children’s diets, individual food items were grouped into the following categories according to their Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies codes 31: milk and milk products; meat, poultry, and fish; eggs; dry beans, peas, legumes, nuts, and seeds; grain products; fruits; vegetables; fats, oils, and salad dressings; and sugars, sweets, and beverages (see also NHANES for similar analysis of dietary recall data grouped by the same categories32). Because grain products have been cited as the largest overall contributor to sodium intake among children32,33, this group was further broken down into its eight subgroups: yeast breads and rolls; quick breads; cakes, cookies, pies, and pastries; crackers and salty snacks; pancakes, waffles, and French toast; pastas, cooked cereals, and rice; cereals, not cooked; and grain mixtures. The relative percentage of sodium consumption from a specific food group was determined as the sum of sodium consumption within that specific food group divided by the sum of sodium consumption from all food groups. The relative proportion of sodium consumption from a specific grain subgroup was determined as the sum of all sodium within that subgroup divided by the sum of sodium consumption from all grain products subgroups. The Goldberg cutoff was applied to eliminate low-energy reporters prior to analysis of reported dietary intake data 34.

Data Analysis

NaCl and MSG detection thresholds were normalized by logarithmic transformation to approximate a normal distribution prior to analysis. Independent t-tests were performed to compare primary outcome measures (NaCl and MSG detection thresholds, anthropometric measures, blood pressure, including distribution of normotensive, pre-hypertensive, and hypertensive children, and reported dietary salt intake) between normal weight and overweight/obese children; and dependent t-tests were used to compare thresholds within each weight group. Distribution of blood pressure categories were also examined by sex with independent t-tests. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess relationships between NaCl and MSG detection thresholds with SBP, DBP, anthropometric measures, and reported dietary salt intake, within each weight group (normal weight and overweight/obese). Correlations are reported in Results as the correlation coefficient (r) with degrees of freedom.

In line with study hypotheses, regression analyses were used to test for associations between salty taste thresholds and blood pressure, controlling for reported dietary salt intake, age, and BMI-Z score. Regression analyses were conducted for all children as one group, for normal weight children, and for overweight/obese children. Identical analyses were used to test MSG taste thresholds. All analyses were conducted with Statistica (version 12, 2013, StatSoft Inc.); and criterion for statistical significance was p < 0.05.

Results

Subject Characteristics, Completion of Tasks, and Reported Dietary Intake

As shown in Table 1, the study population consisted of 97 children (53 girls, 44 boys) whose race/ethnicity, family income, and education levels reflected the diversity of the city of Philadelphia 35. None of the children refused to participate and the majority (96.9%) of children completed both MSG and NaCl thresholds (75.3%) or one of the thresholds (21.6%). Only 3% of children did not complete either. Reasons for completing only one or neither of the thresholds included noncompliance with protocol, or the child was too tired, hungry, or distracted to continue testing.

Table 1.

Characteristics of a cohort of 97 pediatric subjects recruited to complete NaCl and MSG taste detection thresholds.

| Characteristic | Pediatric subjects | p-Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All children (N=97) | Normal weight (N=47) | Overweight/obese (N=50) | ||

| Age, years [mean (SEM)] | 10.5 (0.2) | 10.4 (0.3) | 10.7 (0.3) | 0.40 |

| Race [% (n)] | 0.12 | |||

| Black | 51.5 (50) | 48.9 (23) | 54.0 (27) | |

| White | 16.5 (16) | 25.5 (12) | 8 (4) | |

| Asian | 2.1 (2) | 2.1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Other | 29.9 (29) | 23.4 (11) | 36 (18) | |

| Ethnicity [% (n)] | 0.62 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 12.4 (12) | 10.6 (5) | 14.0 (7) | |

| Female [% (n)] | 54.6 (53) | 59.6 (28) | 50 (25) | 0.34 |

| BMI [mean (SEM)] | 21.4 (0.6) | 17.4 (0.3) | 25.1 (0.8) | <0.01 |

| BMI z-score [mean (SEM)] | 0.94 (0.1) | 0.04 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | <0.01 |

| Waist circumference [cm; mean (SEM)] | 72.8 (1.5) | 63.4 (0.8) | 81.6 (2.1) | <0.01 |

| Waist-to-height ratio [cm/kg; mean (SEM)] | 0.49 (0.01) | 0.44 (0.005) | 0.55 (0.01) | <0.01 |

| Percent body fat [mean (SEM)] | 33.5 (1.2) | 24.2 (0.9) | 42.3 (1.1) | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure [mmHg; mean (SEM)] | 111.4 (1.1) | 107.8 (1.3) | 114.8 (1.5) | <0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure [mmHg; mean (SEM)] | 66.0 (0.6) | 65.9 (0.9) | 66.0 (0.8) | 0.97 |

| Blood pressure category [% (n)] b | 0.35 | |||

| Normal | 70.1 (68) | 74.5 (35) | 66.0 (33) | |

| Prehypertensive | 10.3 (10) | 8.5 (4) | 12.0 (6) | |

| Hypertensive | 19.6 (19) | 17.0 (8) | 22.0 (11) | |

| Valid dietary recall [% (n)] | 74.0 (73) | 76.6 (36) | 74.0 (37) | 0.97 |

| Dietary intake [mean (SEM); range)]c | ||||

| Energy intake, kcal/day | 2260.9 (91.4) (1168.0 – 4540.5) |

2090.9 (108.9) (1168.0 – 3979.8) |

2426.2 (142.2) (1338.8 – 4540.5) |

0.07 |

| Sodium, mg/day | 3820.9 (176.0) (1702.5 – 8001.5) |

3432.0 (241.4) (1702.5 – 8001.5) |

4199.2 (242.9) (1947.3 – 7254.6) |

0.03 |

| Sodium densityd | 1697.9 (45.4) 638.6 – 2762.6 |

1637.9 (69.0) 638.6 – 2640.9 |

1756.3 (58.8) 1123.6 – 2762.6 |

0.19 |

| Sodium mg/kg body weight | 93.0 (6.0) 35.3 – 352.1 |

103.9 (10.3) 37.7 – 352.1 |

82.5 (5.9) 35.3 – 183.9 |

0.07 |

| Completion of task [% (n)] | 0.16 | |||

| Completed both MSG and NaCl thresholds | 75.3 (73) | 80.9 (38) | 70.0 (35) | |

| Completed threshold for either MSG or NaCl | 21.6 (21) | 17.0 (8) | 26.0 (13) | |

| Did not complete either MSG or NaCl threshold | 3.1 (3) | 2.1 (1) | 4.0 (2) | |

| Socioeconomic Characteristicse | ||||

| Family income, % (n) | 0.09 | |||

| <$15,000 | 21.6 (21) | 10.6 (5) | 32.0 (16) | |

| $15,000–35,000 | 41.2 (40) | 46.8 (22) | 36.0 (18) | |

| $35,000–75,000 | 25.8 (25) | 29.8 (14) | 22.0 (11) | |

| >$75,000 | 11.3 (11) | 12.8 (6) | 10.0 (5) | |

| Highest level of education [mother; % (n)] | 0.10 | |||

| Grade school | 4.1 (4) | 6.4 (3) | 2.0 (1) | |

| High school | 45.4 (44) | 38.3 (18) | 52.0 (26) | |

| Trade school | 9.3 (9) | 12.8 (6) | 6.0 (3) | |

| College | 37.1 (36) | 34.0 (16) | 40.0 (20) | |

| Graduate school | 4.1 (4) | 8.5 (4) | 0.0 (0) | |

Unadjusted p-values were generated from independent t-tests comparing the means of normal weight and overweight/obese children.

Blood pressure categories were determined according to the National High Blood Pressure Education Program guidelines for classifying hypertension among children28.

Intake data are from one testing day and were collected using the Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Recall, beta version (2009)29. Data included in the table are excluding underreporters eliminated with the Goldberg cutoff.

Sodium density is calculated as (total mg sodium consumed/total kcal consumed) × 1000.

Reported by mother.

Approximately half of children were overweight or obese, and 30% were classified as pre-hypertensive or hypertensive (Table 1). There were no differences in distribution of blood pressure categories by weight (p=0.66), nor by sex (p=0.71). Normal-weight and overweight/obese children were well matched for age, sex, and ethnicity. As expected, overweight/obese children had a higher mean BMI z-score, waist circumference, percent body fat, waist-to-height ratio (a measure of central obesity), and mean SBP compared with normal-weight children.

As shown in Table 1, most children completed dietary recall tasks. About one-fifth were identified as low-energy reporters after the Goldberg cutoff was applied and thus were excluded from analyses of dietary records/reported sodium intake (overweight and obese children were no more likely to underreport than normal weight children (p=0.40). However, findings remained the same when analyses were conducted including low-energy reporters. Of the 73 children that completed and provided dietary recall data that satisfied the Goldberg cutoff, all reported excessive sodium intake that failed to meet the recommended 1,500 mg per day from the 2010 Dietary Guidelines36.

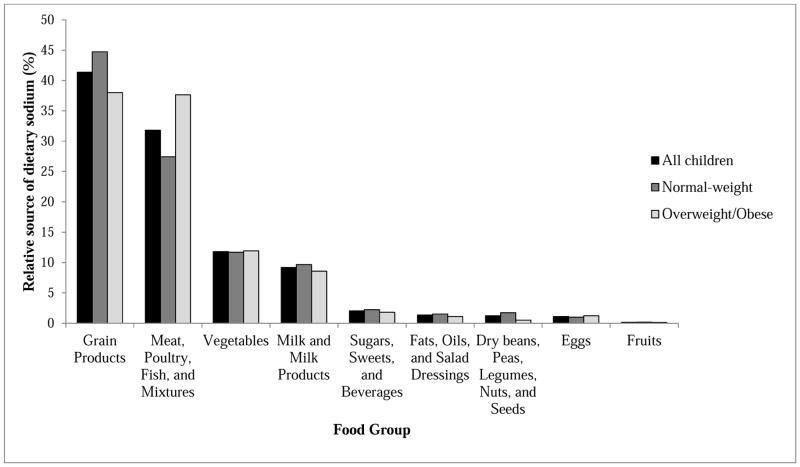

Overweight/obese children consumed more sodium than normal-weight children and tended to consume more calories (Table 1). For both normal-weight and overweight/obese children, grain products were the largest relative contributor to reported sodium intake (Figure 2), though meat, poultry, and fish were a significant contributor to reported sodium intake among overweight/obese children as well (specifically, hot dogs, sausages, and ham). Within the grain products group, grain mixtures were the largest relative contributor to reported sodium intake; this subgroup includes pasta and rice mixed dishes, pizza, tacos and nachos, and pasta/grain-based soups.

Figure 2.

Relative sources of dietary sodium among all children, normal-weight children, and overweight/obese children.

Taste Thresholds, Blood Pressure, Body Weight, and Reported Dietary Salt Intake

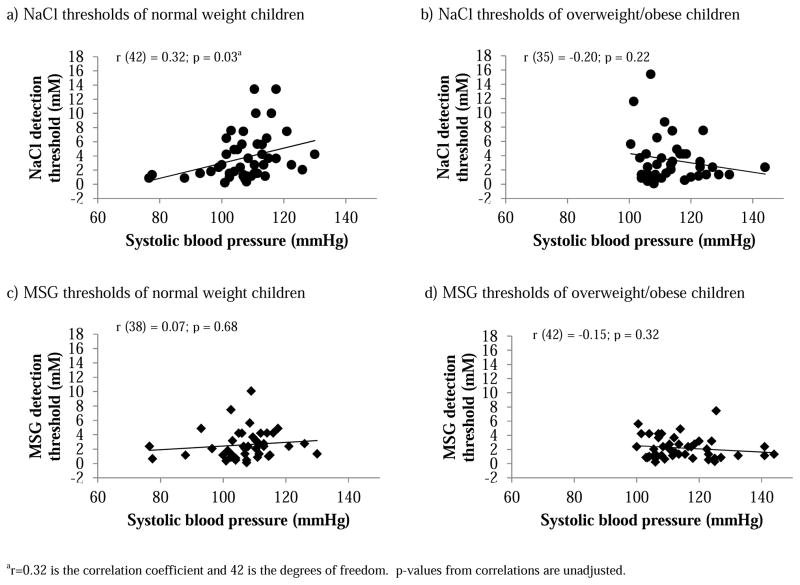

Thresholds for NaCl, and MSG were positively related to each other (r (71) = 0.30; p=0.01, where r = 0.30 is the correlation coefficient and 71 is the degrees of freedom). Thresholds for either tastant did not differ between normal-weight and overweight/obese children (Table 2) and were not related to BMI z-scores, waist circumference, waist-to-height ratio, reported dietary salt intake, or blood pressure in either group. SBP was positively correlated with salty taste detection thresholds among normal-weight children (Figure 3a) but not among overweight/obese children (Figure 3b); this relationship was not evident for MSG thresholds for either group (Figure 3c,d).

Table 2.

MSG and NaCl taste detection thresholds in a cohort of 97 pediatric normal-weight and overweight/obese subjects [mean ± SEM (n)].

| Measure | All children | Normal weight | Overweight/obese | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSG threshold (mM) | 2.4 ± 0.2 (84) | 2.2 ± 0.2 (40) | 2.7 ± 0.1 (44) | 0.23 |

| NaCl threshold (mM) | 3.6 ± 0.3 (83) | 3.7 ± 0.3 (44) | 3.4 ± 0.3 (39) | 0.75 |

| p-Valueb | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

Comparisons between normal weight and overweight/obese groups were made with independent t-tests. p-values are unadjusted.

Comparisons between MSG and NaCl thresholds within each group were made with dependent t-tests. p-values are unadjusted.

Figure 3.

Association between NaCl (a, b) and MSG (c, d) detection thresholds and systolic blood pressure (SBP) among normal-weight (a, c) and overweight/obese children (b, d) as determined with Pearson correlations.

Of the covariates used in multiple regression analyses (SBP, DBP, reported dietary salt intake, BMI-Z score, and age), only SBP was significantly correlated with salty taste thresholds, and only among normal weight children; there were no significant relationships between variables when analyses were completed on all children as one group or on overweight/obese children, nor were there any relationships with MSG taste thresholds for any of the groups. A model including all covariates accounted for 25% of the variance in salty taste thresholds among normal weight children, F (5, 32) = 2.7, p = 0.01, R2 = 0.25, 90% CI [0.0003, 0.002].

Discussion

In light of the growing concern regarding high dietary salt intake and increased prevalence of high blood pressure among pediatric populations, we examined the relationship of salty taste sensitivity with blood pressure, body weight, and reported dietary salt intake in a racially diverse population of 8- to 14-year-old children from the Philadelphia area. We found a positive correlation between salty taste thresholds and SBP among normal-weight children but not among overweight and obese children, a relationship that did not extend to MSG thresholds. Thresholds for both tastants were within the range previously reported for both adults 22,37 and children 8; however, there was no difference in either MSG or NaCl thresholds between normal-weight and overweight/obese children, as has been reported in adults 22,38. The lack of a relationship between detection thresholds and obesity among children warrants future exploration of whether alterations in taste sensitivity are a consequence of years of obesity.

A relationship between salty taste sensitivity and SBP has been observed previously in children. Salty taste detection thresholds were positively correlated with SBP among non-obese but not among obese Spanish children8. Among normal- and underweight Nigerian children, salty taste recognition thresholds were positively correlated with SBP (overweight and obese children were not included in the study); in addition, no relationship between SBP and thresholds for sucrose, urea, or hydrochloric acid was observed, indicating the relationship was specific to salty taste 9. To our knowledge, no adult studies have examined the relationship among salty taste sensitivity, SBP, and body weight—all studies to date have instead examined differences in salty taste sensitivity between normotensive and hypertensive subjects6,12,13. Future research is needed to investigate whether the observed relationship between blood pressure and taste sensitivity for salt is also evident in normal weight adults.

Several explanations, not mutually exclusive, may explain the association between blood pressure and salt sensitivity among normal-weight but not obese/overweight children. First, the observed differences may be due to differences between the groups in the ability to measure detection thresholds. This seems unlikely, however, as there were no differences in ability to comprehend or complete the task. Furthermore, only children who completed the task were included in the final analyses, and the findings were specific to NaCl and did not extend to MSG thresholds.

Second, salty taste detection thresholds may not be related with SBP among overweight/obese children because of their relatively higher blood pressures compared with normal-weight children; that is, the relationship may not have been observed due to a ‘ceiling effect’. On average, the SBP of overweight/obese children in our study was significantly higher than that of normal weight children. In addition, the overall range of SBPs among overweight/obese children (100 – 144 mm Hg) was more similar to the range of SBPs one might expect to see among healthy, prehypertensive, and stage 1 hypertensive adults collectively (<120 – 159 mm Hg), than it was to the normal weight children in the present study (77 – 130 mm Hg). Perhaps this similarity in blood pressures between overweight/obese children and adults explains why a positive association between SBP and salty taste thresholds has not been observed in either group. Examining whether a reduction in blood pressure of overweight/obese children shifts this relationship, could be an interesting area for future research.

Third, the differences in the relationship between SBP and taste thresholds between the two groups may be due to dietary intake. Overweight/obese children had higher reported dietary salt intake and higher caloric intake than did the normal-weight children. Though this difference in dietary intake did not directly explain the lack of a relationship between blood pressure and taste detection for salt, a previous study reported a positive relationship between salty taste preferences and dietary salt intake (mg/day) among children39. Greater liking of salt may have led to higher salt intake among overweight/obese children, serving as a contributing factor to heightened blood pressure40, which, in turn, may have influenced the relationship between SBP and salty taste sensitivity. Whether high-sodium diets mediate the lack of a relationship between blood pressure and taste sensitivity among obese children is an important area for future research.

The present study highlights three important findings. First, blood pressure is positively associated with salty taste sensitivity among normal weight children. The method for measuring detection thresholds detailed herein addresses the cognitive limitations of children by eliminating the need for a verbal response and has previously been validated20 for assessing both taste and olfaction in children41,42. Second, that the observed relationship did not follow a simple pattern of higher salty taste detection thresholds with higher reported dietary salt intake, suggests overweight and obesity and high blood pressure may have as of yet unresolved consequences on taste. Obese children have a 3-fold higher risk for developing hypertension than non-obese children, regardless of race, ethnicity, and sex43. Weight loss among obese children has repeatedly been shown through observational and interventional studies to result in a drop in blood pressure44–47; assessing the impact of weight loss and reduced blood pressure on salty taste thresholds of overweight and obese children could be an important area for future research, as this has yet to be explored. Third, results from 24-hour dietary recall indicate that children in the present study, regardless of body weight, are consuming salt at levels well in excess of recommendations36,48, and that grain and meat products serve as primary sources of sodium. Should salty taste detection thresholds and blood pressure share a common link, the high rate of pediatric obesity and the current food environment rife with readily available sodium-rich foods49 could be limiting our ability to fully understand the relationship between these variables, underscoring the need for a continued focus on reducing both rates of pediatric obesity and excessive salt intake. Further elucidation of the discussed relationship could be useful for identifying and directing dietary guidance of children susceptible to developing high blood pressure.

Limitations

While the methods described herein were easy for children to comprehend and complete, as expected, not all children completed both thresholds often because they were hungry or could not sustain attention. Nevertheless, it is important for future research on children (as well as adults) to monitor and report failures and noncompliance as part of the research protocol. Although the sample size used for the present study was sufficient for an exploration of the relationship between salty taste sensitivity and blood pressure by body weight, a larger sample would allow for stratification of subjects by race, ethnicity, and sex to account for how these variables might interact to influence sodium intake and blood pressure, particularly since these variables have been shown to be important factors when assessing blood pressure of children50. Although mothers confirmed dietary intake at home, children reported on dietary intake during periods when they were away from home (e.g., school). Because children of this age group are prone to reporting error51, this can be viewed as a limitation. We note, however, that the average daily dietary sodium intake (~3,800 mg) collected from mothers and children via ASA24 in the present study was similar to NHANES data from a national sample of children (~3,300 mg) 52. Future studies would benefit from multiple 24-hour dietary recalls on both weekdays and weekends and from other geographic areas.

Conclusions

In light of the apparent disruption in the relationship between salty taste detection thresholds and blood pressure among overweight and obese children, future research is warranted to further elucidate this relationship, including whether changes in taste perception precede or follow weight gain and heightened blood pressure, and whether variables such as race, sex, and parental income and education have any influence on the observed relationship. Continued investigation in this area has potential to add valuable insight to our current understanding of the associations among taste sensitivity, dietary intake, and health.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susana Finkbeiner and Loma Inamdar for technical assistance; Gary Beauchamp for insightful comments and conversations; and Ms. Patricia J. Watson for her valuable editorial assistance.

Funding/Support Disclosure

This work was supported by the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), National Institutes of Health (NIH) [grant number R01 DC011287], NIH postdoctoral training grant (T32-DC00014), and an investigator-initiated grant from Ajinomoto Co., Inc. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDCD or NIH. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation or contents of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nuala K. Bobowski, Email: nbobowski@monell.org, Monell Chemical Senses Center, 3500 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-3308, phone: 267-519-4891.

Julie A. Mennella, Email: mennella@monell.org, Monell Chemical Senses Center, 3500 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-3308, phone: 267-519-4880, fax: 215-898-2084.

References

- 1.Hoffman HJ, Cruickshanks KJ, Davis B. Perspectives on population-based epidemiological studies of olfactory and taste impairment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:514–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04597.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott P, Stamler J, Nichols R, et al. Intersalt revisited: further analyses of 24 hour sodium excretion and blood pressure within and across populations. Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. BMJ. 1996;312(7041):1249–1253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7041.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauer RM, Filer LJ, Reiter MA, Clarke WR. Blood pressure, salt preference, salt threshold, and relative weight. American journal of diseases of children. 1976;130(5):493–497. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1976.02120060039008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pangborn RM, Pecore SD. Taste perception of sodium chloride in relation to dietary intake of salt. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1982;35(3):510–520. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/35.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schechter PJ, Horwitz D, Henkin RI. Salt preference in patients with untreated and treated essential hypertension. Am J Med Sci. 1974;267(6):320–326. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197406000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zumkley H, Vetter H, Mandelkow T, Spieker C. Taste sensitivity for sodium chloride in hypotensive, normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Nephron. 1987;47 (Suppl 1):132–134. doi: 10.1159/000184571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattes RD, Kumanyika S, Halpern BP. Salt taste responsiveness and preference among normotensive, prehypertensive and hypertensive adults. Chem Senses. 1983;8:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arguelles J, Diaz JJ, Malaga I, Perillan C, Costales M, Vijande M. Sodium taste threshold in children and its relationship to blood pressure. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40(5):721–726. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2007000500017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okoro EO, Uroghide GE, Jolayemi ET. Salt taste sensitivity and blood pressure in adolescent school children in southern Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1998;75(4):199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wotman S, Mandel ID, Thompson RH, Jr, Laragh JH. Salivary electrolytes and salt taste thresholds in hypertension. Journal of chronic diseases. 1967;20(11):833–840. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallis N, Lasagna L, Tetreault L. Gustatory thresholds in patients with hypertension. Nature. 1962;196:74–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azinge EC, Sofola OA, Silva BO. Relationship between salt intake, salt-taste threshold and blood pressure in Nigerians. West African Journal of Medicine. 2011;30(5):373–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Moura Piovesana P, de Lemons Sampaio K, Gallani MCBJ. Association between taste sensitivity and self-reported and objective measures of salt intake among hypertensive and normotensive individuals. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2013 doi: 10.5402/2013/301213. http://dx.doi.org/10.5402/2013/301213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Henkin RI. Salt taste in patients with essential hypertension and with hypertension due to primary hyperaldosteronism. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1974;27(4–5):235–244. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattes RD. The taste for salt in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(2 Suppl):692S–697S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.2.692S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattes RD. Salt taste and hypertension: a critical review of the literature. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37(3):195–208. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Din-Dzietham R, Liu Y, Bielo MV, Shamsa F. High blood pressure trends in children and adolescents in national surveys, 1963 to 2002. Circulation. 2007;116(13):1488–1496. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, Whelton PK. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2107–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He FJ, Marrero NM, Macgregor GA. Salt and blood pressure in children and adolescents. Journal of human hypertension. 2008;22(1):4–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mennella JA, Lukasewycz LD, Griffith JW, Beauchamp GK. Evaluation of the Monell forced-choice, paired-comparison tracking procedure for determining sweet taste preferences across the lifespan. Chem Senses. 2011;36(4):345–355. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjq134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pepino MY, Mennella JA. Sucrose-induced analgesia is related to sweet preferences in children but not adults. Pain. 2005;119(1–3):210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pepino MY, Finkbeiner S, Beauchamp GK, Mennella JA. Obese women have lower monosodium glutamate taste sensitivity and prefer higher concentrations than do normal-weight women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:959–965. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pribitkin E, Rosenthal MD, Cowart BJ. Prevalence and causes of severe taste loss in a chemosensory clinic population. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112(11):971–978. doi: 10.1177/000348940311201110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed September 8, 2014];CDC growth charts: United States. http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/. Published May, 2000.

- 25.Houtkooper LB, Lohman TG, Going SB, Hall MC. Validity of bioelectric impedance for body composition assessment in children. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1989;66(2):814–821. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.2.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyrrell VJ, Richards G, Hofman P, Gillies GF, Robinson E, Cutfield WS. Foot-to-foot bioelectrical impedance analysis: a valuable tool for the measurement of body composition in children. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2001;25(2):273–278. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. [Accessed September 8, 2014];The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. NIH Publication No. 05-5267. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/heart/hbp/hbp_ped.pdf. Published May, 2005.

- 29.Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Recall (ASA24) Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirkpatrick SI, Subar AF, Douglass D, et al. Performance of the Automated Self-Administered 24-hour Recall relative to a measure of true intakes and to an interviewer-administered 24-h recall. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2014;100(1):233–240. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.083238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.USDA. Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 4.1. Beltsville, MD: Agricultural Research Service, Food Surveys Research Group; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Food Categories Contributing the Most to Sodium Consumption — United States, 2007–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(5):92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marrero NM, He FJ, Whincup P, Macgregor GA. Salt intake of children and adolescents in South London: consumption levels and dietary sources. Hypertension. 2014;63(5):1026–1032. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Champagne CM, Delany JP, Harsha DW, Bray GA. Underreporting of energy intake in biracial children is verified by doubly labeled water. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1996;96(7):707–709. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pew Charitable Trust. [Accessed March 6, 2014];A city transformed: the racial and ethnic changes in Philadelphia over the last 20 years. 2011 http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Reports/Philadelphia_Research_Initiative/Philadelphia-Population-Ethnic-Changes.pdf.

- 36.United States Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 7. Washington D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mojet J, Christ-Hazelhof E, Heidema J. Taste perception with age: generic or specific losses in threshold sensitivity to the five basic tastes? Chemical Senses. 2001;26(7):845–860. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.7.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donaldson LF, Bennett L, Baic S, Melichar JK. Taste and weight: is there a link? The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009;90(3):800S–803S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27462Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mennella JA, Finkbeiner S, Lipchock SV, Hwang LD, Reed DR. Preferences for salty and sweet tastes are elevated and related to each other during childhood. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He FJ, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):380–382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt HJ, Beauchamp GK. Adult-like odor preferences and aversions in three-year-old children. Child Development. 1988;59:1136–1143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forestell CA, Mennella JA. Children’s hedonic judgments of cigarette smoke odor: effects of parental smoking and maternal mood. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(4):423–432. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sorof J, Daniels S. Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions. Hypertension. 2002;40(4):441–447. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000032940.33466.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brownell KD, Kelman JH, Stunkard AJ. Treatment of obese children with and without their mothers: changes in weight and blood pressure. Pediatrics. 1983;71(4):515–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarke WR, Woolson RF, Lauer RM. Changes in ponderosity and blood pressure in childhood: the Muscatine Study. American journal of epidemiology. 1986;124(2):195–206. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Figueroa-Colon R, von Almen TK, Franklin FA, Schuftan C, Suskind RM. Comparison of two hypocaloric diets in obese children. American journal of diseases of children. 1993;147(2):160–166. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160260050021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rocchini AP, Katch V, Schork A, Kelch RP. Insulin and blood pressure during weight loss in obese adolescents. Hypertension. 1987;10(3):267–273. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.10.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO. Guideline: Sodium intake for adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maillot M, Drewnowski A. A conflict between nutritionally adequate diets and meeting the 2010 dietary guidelines for sodium. American journal of preventive medicine. 2012;42(2):174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McNiece KL, Poffenbarger TS, Turner JL, Franco KD, Sorof JM, Portman RJ. Prevalence of hypertension and pre-hypertension among adolescents. The Journal of pediatrics. 2007;150(6):640–644. 644 e641. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Livingstone MB, Robson PJ, Wallace JM. Issues in dietary intake assessment of children and adolescents. The British journal of nutrition. 2004;92 (Suppl 2):S213–222. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: food categories contributing the most to sodium consumption - United States, 2007–2008. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(5):92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]