Abstract

Neuroinflammation is a response against harmful effects of diverse stimuli and participates in the pathogenesis of brain and spinal cord injury (SCI). The innate immune response plays a role in neuroinflammation following central nervous system (CNS) injury via activation of multi-protein complexes termed inflammasomes that regulate the activation of caspase-1 and the processing of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. We report here that the expression of components of the nucleotide-binding-and-oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor protein-1 (NLRP-1) inflammasome, apoptosis speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) and caspase-1 are significantly elevated in spinal cord motor neurons and cortical neurons after CNS trauma. Moreover, NLRP1 inflammasome proteins are present in exosomes derived from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of SCI and traumatic brain-injured patients following trauma. To investigate whether exosomes could be used to therapeutically block inflammasome activation in the CNS, exosomes were isolated from embryonic cortical neuronal cultures and loaded with short-interfering RNA (siRNA) against ASC and administered to spinal cord-injured animals. Neuronal-derived exosomes crossed the injured blood-spinal cord barrier, and delivered their cargo in vivo, resulting in knock down of ASC protein levels by approximately 76% when compared to SCI rats treated with scrambled siRNA. Surprisingly, siRNA silencing of ASC also led to a significant decrease in caspase-1 activation and processing of IL-1β after SCI. These findings indicate that exosome-mediated siRNA delivery may be a strong candidate to block inflammasome activation following CNS injury.

Keywords: Inflammasome, exosomes, caspase-1, brain injury, spinal cord injury

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) are complex and devastating clinical conditions characterized by neuronal loss, axonal destruction, and demyelination during the secondary injury cascade (Beattie et al. 2002, Bramlett & Dietrich 2014, Bramlett & Dietrich 2004, Hutchinson et al. 2007, Popovich 2000). Both types of injuries involve multiple factors, including systemic humoral pathophysiological factors in addition to direct central nervous (CNS) injuries. Since cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is in contact with many areas of the brain and spinal cord, it has been suggested that the humoral factors that mediate signaling after CNS injury may be carried and transported in CSF or other body fluids (Street et al. 2012). Recently, it has been shown that CSF contains exosomes that may play a role in humoral signaling in the CNS (Harrington et al. 2009). In the context of CNS pathology, pathogenic proteins such as β-amyloid, prion protein, α-synuclein, tau and superoxide dismutase are released into the CSF in association with exosomes (Emmanouilidou et al. 2010, Fevrier et al. 2004, Gomes et al. 2007, Rajendran et al. 2006, Saman et al. 2012). It has been proposed that exosomes containing pathological proteins mediate the spread of cell damage or alter the microenvironment in various metabolic and nervous system disorders (Fruhbeis et al. 2013, Pant et al. 2012). However, it remains unclear whether exosomes secreted into CSF contribute to molecular signaling in the pathology after CNS injury.

In the CNS, neurons, astrocytes, microglia and oligodendrocytes have been reported to secrete exosomes into the extracellular environment (Chivet et al. 2012, Fruhbeis et al. 2013). Exosomes contain a distinct set of proteins conserved across different cell types and species, e.g., cytoskeletal proteins such as tubulin and actin, heat-shock proteins (Hsp 70 and 90), metabolic enzymes of glucose metabolism, flotillin-1, signal transduction proteins (kinases, heterotrimeric G proteins), MHC molecules, clathrin, proteins involved in transport and fusion (annexins, Rab proteins), and translation elongation factors. In terms of the mechanisms responsible for the activation of the immune response, recent reports suggest that exosomes carry bioactive cytokines such as IL-1β as well as inflammasome components (Qu et al. 2007) and that exosomes regulate Toll-like receptor signaling and IL-1β production by the NLRP3 inflammasome (Haneklaus et al. 2013).

Evidence suggests that exosomes trigger an innate immune response that amplifies such response via the cargo of proteins, RNA and miRNA that transfer immune responsiveness to neighboring cells. Exosome content and functions depend on the precise maturation stage, cell lineage, and stimulation state of the parent immune cell (Pant et al. 2012). In fact, immune functions of exosomes can be tailored to be immunogenic or tolerizing, depending on the presence of specific molecular cargo. Moreover, exosomes have been used in creating highly specialized therapeutics termed “designer dexosomes” that are utilized in cancer therapy, vaccine development and transplant tolerance induction (Viaud et al. 2010).

Here we show that exosomes derived from neurons can deliver short-interfering RNA (siRNA) into the CNS to significantly decrease inflammasome activation after injury. We also found that inflammasome protein expression in exosomes derived from CSF in TBI and SCI subjects was increased after CNS trauma. Thus, exosomes offer a new therapeutic approach to deliver RNA-based drugs to block inflammation after CNS injury.

Materials and Methods

Neuropathological Procedures

For immunohistochemical analysis of inflammasome proteins spinal cord sections were obtained from The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis’ Human Spinal Cord Bank. Spinal cords from 9 cases of SCI (8 males and 1 female with ages ranging from 20 to 77 years) who sustained vertebral fractures were used in this study (Table 2). SCI was classified on the basis of histological appearance as “contusion/cyst”, massive compression or laceration as described (Fleming et al. 2006) (Table 1). Brain sections used for immunohistochemistry correspond to brains from healthy decedents.

Table 2.

Subjects used in this study (CSF)

| Patient | Age | Gender | Race | Mechanism of Injury | Spinal Injury | AIS Grade | Level | Surgery | Hypothermia | Exam at Rehab D/C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | M | White | Diving accident | C5/6 Fracture dislocation | A | C5 | C5/6 Anterior discectomy & fusion | Yes | C5 ASIA C |

| 2 | 19 | M | Black | Motor vehicle accident | C4/5 Bilateral jumped facets | B | C4 | C4/5 Anterior discectomy & fusion | No | C4 ASIA D |

| Exosomes experiement | 22 | M | White | Rugby accident | C5/6 Bilateral jumped facets | A | C5 | C5/6 Anterior discectomy & fusion | Yes | C6 ASIA A |

| Spinal Cord Injury | ||||||||||

| Patient | Age | Gender | Mechanism of Injury | Type of Injury | GCS | ISS | Motor | Surgery | Hypothermia | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23 | M | Motor vehicle accident | Subdural and Epidural hematoma, refractory high ICP | 5 | 25 | 3 | Cranial Decompression and Craniotomy | Yes | Developing vegetative state, Infarcts on CT |

| 2 | 29 | M | Motor vehicle accident | DAI suspected | 7 | 25 | 5 | None | No | Following Commands |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | ||||||||||

In all cases, tissue samples from the center of SCI and at various distances above and below the injury were obtained. In this study we analyzed inflammasome protein expression of diaminobenzidine (DAB) immunostained sections at the epicenter, penumbra and an area distal from the epicenter.

All tissue samples were removed within 24 h of death and fixed in neutral buffered formalin as previously described. Blocks from the spinal cords were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin wax, cut into 6 μm thick sections and placed on positively charged glass slides. One set of sections was stained with hematoxylin and the remaining sets were used for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with anti-NLRP1 (Bethyl Laboratories as described (de Rivero Vaccari et al., 2008), anti-caspase-1 (Upstate), and anti-ASC (Chemicon) using DAB as the chromophore along with hematoxylin. Negative controls included sections in which the primary antibody was omitted, sections incubated with isotype-matched antibodies (1:200) and controls using secondary antibodies alone. These negative controls were processed with every batch of immunohistochemical slides.

Neuropathological Assessment

The cord and brain were assessed microscopically, using brightfield optics, by examining H&E or H&E/DAB-stained sections from the epicenter, penumbra and uninvolved area distal from the epicenter.

CSF samples

The study was approved by the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (Protocol #20090655 for SCI sample collection and protocol #20030154 for TBI sample collection). The CSF of 7 patients with SCI was used to analyze the levels of inflammasome protein expression after injury. The American Spinal Cord Injury Association (ASIA) scale of these patients at admission to the emergency department ranged from AIS A to B. Information regarding the diagnosis, procedures and outcomes are shown in Table 1. CSF from uninjured individuals was obtained as a control from patients ranging from 29 to 91 years old. Patients in the control group required a ventriculostomy for non-traumatic pathology. SCI CSF samples were obtained from patients (n = 6) at different time points after injury. CSF was collected from patients who suffered a severe, traumatic SCI that revealed a dural laceration as determined at the time of surgical decompression and stabilization. These patients underwent therapeutic diversion of CSF using a silastic catheter drain placed after surgery. Informed consent was obtained directly from the patient and family after all the potential risks and benefits were fully explained, and patients were only considered for study enrollment if a lumbar drain was already clinically necessary. CSF was collected every 12 hours as the clinical status and drain function permitted for a total of up to 6 days following injury. 5 cc aliquots of CSF were obtained at each time interval and immediately spun in a centrifuge to remove cellular material and debris before protein analysis. There were no complications as a result of drain placement or fluid removal (Table 2).

For CSF collection of brain-injured patients samples were collected from patients that suffered severe TBI (GCS 8 or less) every 6 hours as the clinical status and drain function permitted for a total of up to 5 days following injury. 2 cc aliquots of CSF were obtained at each time interval and immediately spun in a centrifuge to remove cellular material and debris before protein analysis. There were no complications as a result of drain placement or fluid removal (Table 2).

Immunoblotting

For detection of inflammasome proteins, CSF samples were mixed with Laemali buffer. In all experiments 5 μg of protein were loaded. Immunoblot analysis was carried with the Criterion system (Bio-Rad) as described (de Rivero Vaccari et al., 2008) using antibodies (1:1000 dilution) to NLRP1 (Millipore), Caspase-1 (Novus Biologicals) and ASC (Santa Cruz). Proteins were resolved in 14-20% TGX Criterion precasted gels (Bio-Rad), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) transfer membranes (Tropifluor – Applied Biosystems) and placed in blocking buffer (PBS, 0.1% Tween-20, 0.4% I-Block (Applied Biosystems) and then incubated for one hour with primary antibodies. Membranes were then incubated for one hour with anti-mouse, anti-rat or anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked antibodies. Signal visualization was performed by enhanced chemilluminescence (Cell Signaling). All images analyzed were done with the same film exposure of 7 minutes in order to maintain all patients under the same conditions for comparison purposes.

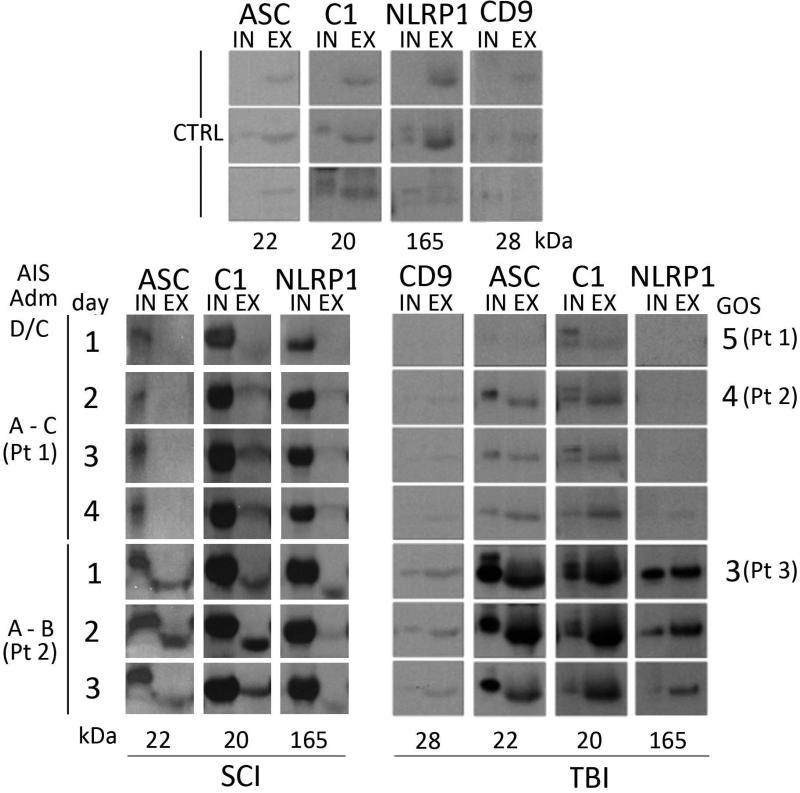

Isolation of Exosomes from CSF and Neuronal Cell Cultures

Exosomes were isolated from CSF samples using ExoQuick (System Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Approximately 2 μg of protein from CSF input (IN) and isolated exosome fractions (EX) were analyzed by immunoblotting for exosome-enriched protein expression (Figure. 3). Glasgow Outcome Scores (GOS) for each TBI patient are shown to the left of the immunoblots. CD9, an exosomal marker, was used as a marker for exosome-positive fractions. Caspase-1 and NLRP1 are enriched in the exosomal fractions from patients with poor outcome (GOS-3). ASC is enriched in the exosomal fraction from two of the three patients with poor outcome. Molecular weights in kilodaltons are shown beneath each protein. To obtain neuronal exosomes, primary neuronal cell cultures were grown from E-18 rat brains as described (Adamczak et al. 2014). Primary rat cortical neuronal cultures were grown for 7 days and culture medium was collected and exosomes were extracted using ExoQuick (System Biosciences) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Figure 3. ASC, Caspase-1, and NLRP1 are released into CSF in association with exosomes.

2 μg of protein from CSF from spinal cord and brain injured samples (IN: input) and isolated exosome fractions (EX) were analyzed by immunoblotting for exosome-enriched protein expression. AIS and GOS for each SCI and TBI patient, respectively, are shown to the left and right of the immunoblots. CD9, confirms exosome-positive fractions. C1 and NLRP1 are enriched in the exosomal fractions from patients with poor outcome (AIS B and GOS-3). ASC is enriched in the exosomal fraction from two of the three patients (Pt.) with poor outcome after TBI. Molecular weights in kDa are shown.

siRNA and exosome loading

psiRNA labeled with GFP against ASC was purchased from InVitrogen, (Grand Island, NY). Exosome loading of psiRNA was carried out as described (Alvarez-Erviti et al. 2011). Briefly, exosomes at a total protein concentration of 12 μg (measured by Bradford assay) and 400 nanomoles (for cell culture) or 12 μg (for in vivo injections) of psiRNA were mixed with 400 μl of electroporation buffer (1.15 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.2, 25 mM potassium chloride, 21% Optiprep) and electroporated in a 4 mm cuvette. For in vivo experiments, electroporation was performed in 400 μl and pooled together before resuspension in a volume of 5% glucose corresponding to 80 μl per injection.

In vitro delivery of siRNA by targeted exosomes

To assess whether neuronal-derived exosomes loaded with siRNA can be used to deliver their cargoes in vitro, we used primary rat cortical neuronal cultures grown for 7 days. Culture medium was harvested and exosomes were extracted using ExoQuick. Exosomes at a total protein concentration of 12 μg (measured by Bradford assay) and 400 nanomoles siRNA-GFP against ASC or scramble siRNA-GFP were mixed with 400 μl of electroporation buffer (1.15 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.2, 25 mM potassium chloride, 21% Optiprep) and electroporated in a 4 mm cuvette. Neurons were treated for 72 hours with exosomal preparations. High delivery efficiency was confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy (data not shown). The knockdown of ASC protein was specific with a knockdown efficiency of approximately 32%.

Spinal cord injury

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Miami. Adult female Fischer rats (180-200g) were used in these studies. The rat model of moderate contusive SCI employed was as described (Keane et al. 2001) with minor modifications. Briefly, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (2%), and then a laminectomy was performed at vertebral level T8 and the cord was exposed without disrupting the dura. A moderate injury was induced using the New York University weight drop device (10 g, 12.5 mm). After injury, muscles were closed in layers, and the incision was closed with wound clips. Rats were returned to their cages and placed on computer-controlled warmed blankets, with access to water and food ad libitum. Gentamycin (5 mg/kg intramuscular) was given once a day for a week following surgery to control infection, while buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg subcutaneous) was given twice a day for 3 days after injury to relieve pain. The rats’ bladders were manually voided twice a day until they were able to regain normal bladder function. Rats were sacrificed 24 hrs after SCI. Sham rats were used as control.

Determination of effect of siRNA to injured spinal cord by systemic injection of targeted exosomes

Exosomes for in vivo experiments were spun down and resuspended in 80 μl of 5% glucose immediately before femoral artery injection. Approximately 150 μg of exosomes and the encapsulated siRNA (150 μg of inflammasome protein psiRNA) was injected via femoral artery per animal at 30 min after SCI. Three groups of rats were used in these studies: 1) sham-operated; 2) spinal cord injured injected with siRNA encapsulated exosomes; 3) spinal cord injured injected with unmodified exosomes. To characterize the tissue distribution, we performed immunoblot analysis of spinal cord lysates. Systemic administration of unmodified exosomes was run as a control. To assess whether exosome-mediated siRNA delivery reduces the innate immune response in vivo, we assessed the levels of innate immune proteins by immunoblot analysis as described (de Rivero Vaccari et al. 2008).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons between groups were done using a one-tailed Student's t-test for experiments involving two groups: Exosome control vs. exosome siRNA against ASC and siRNA vs. scrambled. P-value of significance was set at P < 0.05. When more than two groups were compared, a ONE way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test was used.

Results

Immunohistochemical Expression of NLRP1 Inflammasome Proteins in the Spinal Cord and Brain After Injury

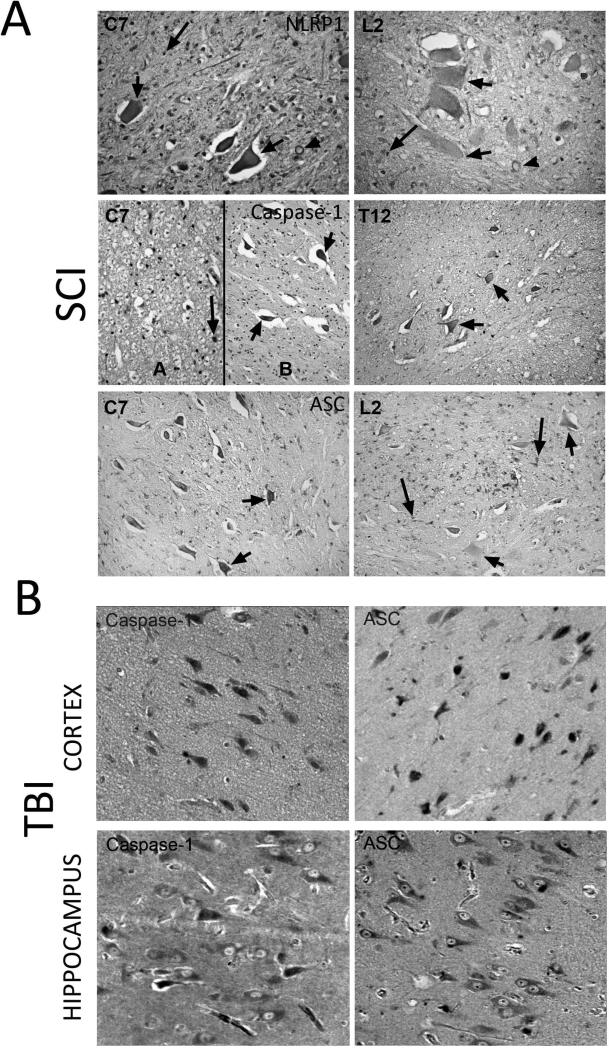

Spinal cord sections were obtained from decedents who had SCI. Immunohistochemical analysis combined with light microscopy indicated that NLRP1 is expressed in neurons of the ventral horn (short arrows), myelinated axons (arrow heads) and oligodendrocytes (long arrows) (Figure 1A). Hematoxylin-stained oligodendrocyte nuclei appear round, whereas microglial nuclei are irregular in shape. Moreover, NLRP1 immunoreactivity in the penumbra (C7) was higher than in areas far distant to the penumbra (L2). Therefore, it appears that inflammasome protein expression is altered in areas distant to the primary lesion site, suggesting that large areas of the spinal cord show an innate immune inflammatory response after injury.

Figure 1. NLRP1 inflammasome proteins are expressed in cells of the CNS.

Spinal cord and brain sections were obtained from decedents that had injury to either the spinal cord (A) or the brain (B). (A) NLRP1 is expressed in neurons of the ventral horn (short arrows), myelinated axons (arrowheads) and oligodendrocytes (long arrows); moreover, NLRP1 immunoreactivity in areas of the penumbra (C7) was higher than in areas distant to the penumbra (L2). Caspase-1 was detected in swollen axons (spheroids, arrow heads), in motor neurons (short arrows) of the ventral horn, and in the white matter in oligodendrocytes (long arrows). At areas distal to the epicenter (T12), caspase-1 was also present in motor neurons (short arrows) but with decreased immunoreactivity than the penumbra (C7). ASC was present in the penumbra (C7) and distal to the epicenter (L2) in neurons in the ventral horn (black arrows), white matter oligodendrocytes (long arrow) and in macrophages/microglia at the epicenter (short arrow). (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of brain sections indicates that caspase-1 and ASC immunoreactivity is present in the cortex and hippocampus of humans.

In addition, DAB immunoreactivity for caspase-1 was detected in swollen axons (spheroids, arrow heads) (Figure 1A), and arterioles (not shown). At areas of the penumbra, caspase-1 staining was present in motor neurons (short arrows) of the ventral horn, and was present in the white matter in oligodendrocytes (long arrows). Caspase-1 immunoreactivity in oligodendrocytes (long arrows) was the same at all levels of the spinal cord examined, regardless of proximity to the epicenter. At areas distal to the epicenter (T12), caspase-1 was also present in motor neurons (short arrows) but with decreased immunoreactivity than the penumbra (C7). These findings indicate that caspase-1 immunoreactivity in neurons may decrease as function of the distance from the epicenter, similar to NLRP1.

In the penumbra (C7) and distal to the epicenter (L2), neurons in the ventral horn (black arrows) and white matter oligodendrocytes (long arrow) showed ASC immunoreactivity. In addition, ASC was also present in macrophages/microglia at the epicenter (short arrow). Moreover, ASC immunoreactivity was also detected in the substantia gelatinosa (dorsal horn) at C7 and L2 (not shown).

Caspase-1 and ASC were also noted in cortical and hippocampal neurons following TBI (Figure 1B) indicating that neurons predominantly show increased inflammasome expression following CNS injury. Thus, it appears that CNS trauma induces increased NLRP1 inflammasome protein immunoreactivity in CNS neurons, and these findings are consistent with previous work demonstrating inflammasome protein expression in neurons, oligodendrocytes and microglia after SCI in rats (de Rivero Vaccari et al. 2008).

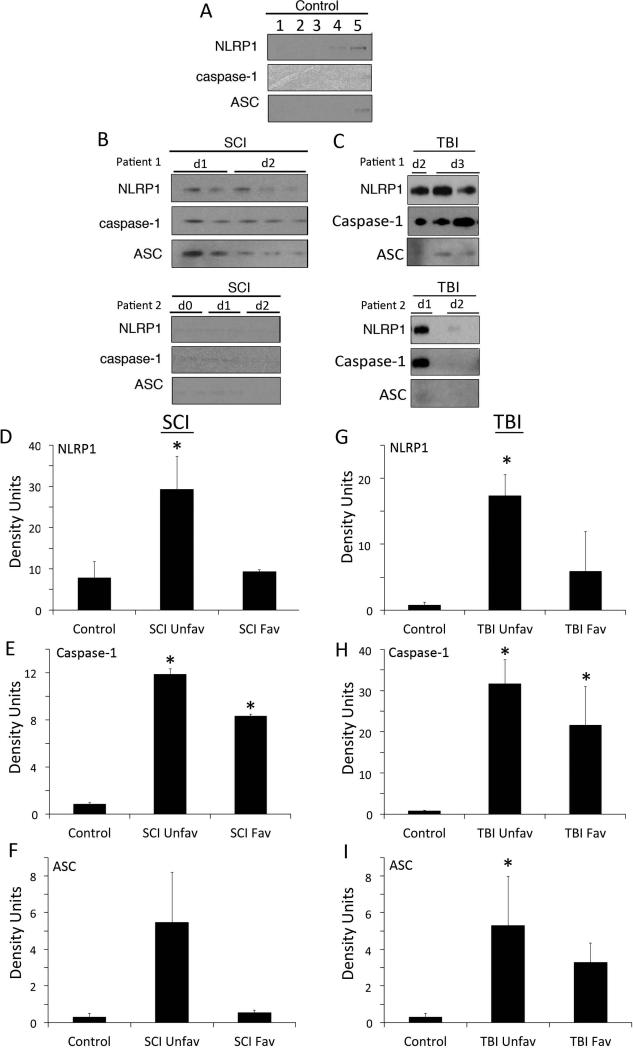

NLRP1 Inflammasome proteins are present in the CSF of Patients with TBI and SCI

To determine whether inflammasome proteins were present in CSF after TBI and SCI, we analyzed CSF samples by immunoblotting from uninjured controls (Figure 2A) and SCI (Figure 2B) and TBI (Figure 2C) individuals with antibodies against NLRP1, caspase-1 and ASC. Control samples contained very low levels of NLRP1 inflammasome proteins. In contrast, immunoblot analysis of 2 different SCI patients (Figure 2B, D, E, F) and 2 different TBI patients (Figure 2C, G, H, I) showed an increase in the levels of NLRP1, caspase-1 and ASC in the CSF when compared to control subjects. It should be noted that SCI patient 1 showed high levels of inflammasome proteins at days 1 and 2 (d1, d2) after SCI and had a poor prognosis, whereas patient 2 had low levels of inflammasome proteins acutely after SCI and had a good prognosis. Similarly, after TBI, patient 1 expressed higher levels of inflammasome proteins than patient 2, consistent with patient 2 having a less severe injury (GCS 7 vs. 5, Table 2). Thus, these findings are consistent with our previous study after TBI showing that individuals that present with low levels of caspase-1 in the CSF early after CNS injury may have a better prognosis than those individuals who show increased levels of these proteins. Further studies that include more patients are needed to accurately determine the predictive value of inflammasome proteins in the CSF on outcomes after CNS injury (Adamczak et al. 2012).

Figure 2. NLRP1, caspase-1 and ASC are elevated after SCI and TBI.

(A) CSF samples from uninjured patients were used as controls (1-5). (B) CSF samples were immunoblotted with antibodies against NLRP1, caspase-1 and ASC. d0 = day of injury and d1, d2 = day 1 and day 2 after injury. Immunoblot analysis of 2 different cases of patients with SCI indicates an increase in the levels of NLRP1 (D), caspase-1 (E) and ASC (F) in the CSF of patients with SCI when compared to CSF from control subjects (patient 1). Patient 2 presented lower levels of inflammasome proteins in the CSF and had a better AIS score at discharge than patient 1 (D vs. C). (C) Immunoblot analysis of 2 different cases of patients with TBI indicates an increase in the levels of NLRP1 (G), caspase-1 (H) and ASC (I) in the CSF of patients with TBI when compared to CSF from control subjects (patient 1). Patient 2 presented lower levels of inflammasome proteins in the CSF and had a better GCS than patient 1 (7 vs. 5). Data are presented as mean ± SEM * P<0.05, N = 3 to 6 per group. UnFav = unfavorable outcome after injury; Fav = favorable outcome after injury.

Inflammasome Proteins are secreted in CSF Exosomes After SCI and TBI

To determine whether inflammasome proteins are secreted in association with exosomes in CSF after CNS trauma, we isolated exosomes from TBI and SCI patients and analyzed inflammasome protein expression using immunoblot analysis (Figure 3). ASC, NLRP1 and caspase-1 (C1) were present in CSF of SCI and TBI patients and non-trauma controls. NLRP1, ASC and caspase-1 (p20) were released into CSF in association with exosomes (Figure 3). However, in each case, the inflammasome proteins in exosomes ran slightly faster on SDS PAGE, indicating that these proteins in exosomes are lower in molecular weights than those in CSF alone. Glasgow Outcome Scores (GOS) for each TBI patient and AIS scale for SCI patients show that caspase-1 and NLRP1 are enriched in the exosomal fraction from two of the three patients with poor outcome.

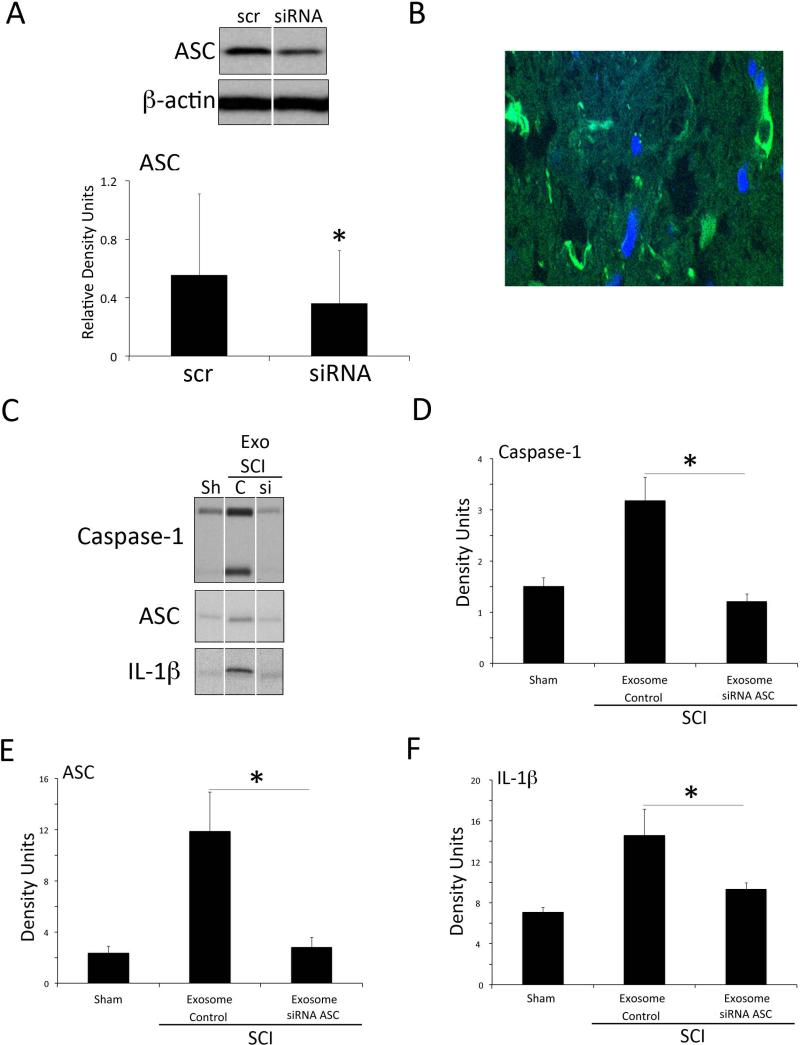

In vitro and in vivo delivery of siRNA by neuronal derived exosomes

To explore whether exosomes may be used as a therapeutic treatment to block inflammasome activation after SCI, we first assessed whether neuronal-derived exosomes loaded with siRNA against ASC would be able to deliver their cargoes in vitro (Figure 4A). Rat cortical neurons were grown for 7 days, the culture medium was collected and exosomes were extracted. Exosomes were loaded with either siRNA-GFP against ASC or scrambled siRNA-GFP and added to cortical neurons for 72 hours. After 72 hours of exosome treatment, the knockdown of ASC protein was specific with a knockdown efficiency of approximately 32% (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Delivery of siRNA with neuronal derived exosomes results in ASC gene knockdown.

(A) siRNA against ASC or scrambled siRNA (Scr) was encapsulated in neuron-derived exosomes and added to primary rat cortical neurons for 3 days resulting in decreased ASC expression. Data are presented as mean ± SEM * P<0.05, N=3 per group. (B) Immunohistochemical image of GFP positive cells in the spinal cord after siRNA against ASC was encapsulated in neuron-derived exosomes and delivered after injury in rats. (C) Representative gels of spinal cord lysates from sham animals (sh), scrambled siRNA treated animals (C) and siRNA-treated animals (si) that were immunolobotted for caspase-1 (D), ASC (E), IL-1β (F) and CD63. Quantification of immunoblots shows that knockdown efficiency of ASC protein was approximately 32%. Data are presented as mean ± SEM * P<0.05 versus scrambled. N= 5 to 6 per group.

Next, we investigated the potential for exosome-mediated systemic siRNA delivery in vivo. To establish whether exosomes crossed the blood-spinal cord barrier, penetrated into the spinal cord parenchyma and delivered their cargo, exosomes containing si-RNA-GFP were injected into the femoral vein at 30 min after SCI and after 24 hrs. The spinal cord was harvested, sectioned and examine by immunofluorescence microscopy. As shown in Figure 4B, cells in the injured spinal cord were GFP-positive in the lesion epicenter (C5) but not in areas distant to the epicenter, indicating that neuronal-derived exosomes effectively delivered their cargo in vivo.

To confirm the therapeutic potential of neuronal exosomes in vivo, we next investigated delivery of siRNAs that silenced ASC protein expression (Figure 4 C-F). Exosomes loaded with siRNA against ASC knockdown ASC protein expression approximately 76% when compared to SCI rats treated with scrambled siRNA (Figure 4C). ASC knockdown also lead to a significant decrease in caspase-1 activation (Figure 4D) and processing of IL-1β (Figure 4F) after SCI, indicating exosome-mediated siRNA delivery may be a strong candidate to block inflammasome activation following SCI.

Discussion

Despite recent advances in uncovering pathomechanisms of secondary injury, there are no effective therapeutic targets to treat SCI or TBI. Our results show that in humans, NLRP1 inflammasome proteins are expressed in neurons following trauma. These inflammasome proteins are released into the CSF in exosomes in patients following CNS trauma. Moreover, exosome-mediated systemic siRNA delivery against ASC significantly decreased inflammasome activation following SCI and decreased caspase-1 activation and processing of IL-1β in rodents. Thus, exosomes offer a new therapeutic alternative to deliver RNA drugs to block inflammation after CNS injury.

Exosomes are bioactive vesicles derived from the cell's endosomal membrane system and are secreted into surrounding body fluids. Exosome formation, cargo content, and delivery to surrounding cells are of immense biological importance considering the role exosomes play in various pathological conditions (Pant et al. 2012, Taylor & Gercel-Taylor 2011). Exosomes exhibit anti-inflammatory or pro-inflammatory properties depending on the parent antigen-presenting cell's conditioning. For example, exosomes are enriched in major histocompatibility (MHC) class I and II antigens and play a role in stimulation of immune responses (Filipazzi et al. 2012, Pant et al. 2012). A recent report suggests that exosomes carry bioactive cytokines such as IL-1β and inflammasome components (Qu et al. 2007). Through this mechanism, exosomes trigger an innate immune response and amplify such response via the cargo of protein, RNA or miRNA that transfers immune responsiveness to neighboring cells.

Our results showing that exosomes are increased in CSF after SCI and TBI indicate a new unexplored role of exosomes in immune function after CNS trauma. The fact that both TBI and SCI are associated with altered vascular permeability possibly enhances the movement of exosome trafficking into CSF pools (Bramlett & Dietrich 2014, DeFazio et al. 2014, Figley et al. 2014, Lotocki et al. 2009). However, it will be important to trace the cell lineage producing these exosomes. In the CNS, neurons, astrocytes, microglia and oligodendrocytes have been reported to secrete exosomes into the extracellular environment (Chivet et al. 2012, Fruhbeis et al. 2013). Exosomes contain a distinct set of proteins that are conserved across different cell types and species. Examples of these include cytoskeletal proteins such as tubulin and actin, heat-shock proteins (Hsp 70 and 90), metabolic enzymes of glucose metabolism, Flotillin-1, signal transduction proteins (kinases, heterotrimeric G proteins), MHC molecules, clathrin, proteins involved in transport and fusion (annexins, Rab proteins), and translation elongation factors. Strikingly abundant are proteins of the tetraspanin family (CD9, CD63, CD81, CD82) (Thery et al. 2009, van Niel et al. 2006). Our observation that cultured neurons secrete innate immune proteins in exosomes indicates a new unexplored role of exosomes in immune function regulation. Moreover, since exosomes reflect the cell's content, they provide a means for “liquid biopsy”, and the cell- and condition-specific cargos may be used as potential biomarkers (Clayton 2012, Diaz-Arrastia et al. 2014, Forde et al. 2014, Papa et al. 2014, Pouw et al. 2014, Yokobori et al. 2013). As shown in our recent publication, CSF from TBI patients contain innate immune proteins that may predict functional outcomes (Adamczak et al. 2014).

These data suggest a role for exosomes in the innate immune response after CNS injury in that they shuttle functional innate immune molecules, thus influencing the inflammasome signaling properties within the CNS. These findings show that exosomes loaded with siRNA specifically deliver their cargo and silence ASC, a key component of inflammasome signaling after SCI and TBI (de Rivero Vaccari et al. 2009, de Rivero Vaccari et al. 2008) in cells of the CNS. Thus, the neuronal-derived exosomes loaded with exogenous genetic cargoes may offer a novel therapeutic strategy to block inflammation after CNS trauma. In support of this idea is the recent report that demonstrates the therapeutic potential of exosome-mediated siRNA delivery to knock down mRNA and protein of the BACE1 protein, a therapeutic target in Alzheimer's disease (Alvarez-Erviti et al. 2011).

What is clear is that an improved knowledge of the components of inflammasomes and the interactions that govern their function will enhance our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of inflammatory cytokine production. Such information will be applicable to diverse pathologies, including CNS trauma, mental retardation, seizure, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, HIV encephalitis, dementia, and ischemic injury (Block & Hong 2005, Dirnagl et al. 1999, Lucas et al. 2006). This understanding may give rise to new insights into biologically relevant targets to control inflammatory diseases, altered blood-spinal cord barrier or infections, complementing or replacing existing therapies that are hindered by limited clinical efficacy or excessive adverse complications.

Table 1.

DATA OF SPINAL CORD DECEDENTS USED FOR IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

| Case | Age | Gender | Pathology Report |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 77 | Female | African American female involved in a motor vehicle accident (MVA). The injury was contusive at the level of C2 characterized by central white/gray matter necrosis, hemorrhage, edema and axonal swelling. The cerebellum and pons showed anoxic changes. There was a radiculopathy associated with posterior column degeneration (remote and unrelated to trauma). The subarachnoid spaced showed sloughed off cerebellar tissue at C1-C2 associated with tonsillar herniation) and central gray microglial proliferation was present at C4-C7. |

| 9 | 26 | Male | African American decedent who sustained multiple gunshot wounds to the neck, chest, abdomen and lower and upper extremities. The injury was cuntission-type with the epicenter at C7 and extending from C2 to T1 with multifocal gray and white hemorrhages associated with parenchymal fragmentation, axonal spheroids, neuronal necrosis and mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates. A subarachnoid hemorrhage was present, C7 to T1, A cervical CT scan showed intact cervical vascular structures, fracture of the left pedicle and the spinous process at C5, fractures of bilateral lamina/pedicles/facets at C6 and C7, spinous process fracture at C7 (associated with bullet fragments), fractures of the right lamina transverse process at L3 and of the right transverse process at L1/L2. No bony or bullet fragments within the lumbar spinal cord were found. The calvarium, brain, dura and leptomeninges were unremarkable. |

| 10 | 20 | Male | Caucasian male involved in a MVA. Decedent had a dislocation of the third thoracic vertebra with associated pink discoloration of the spinal cord parenchyma, and mild subarachnoid hemorrhage was present at T1, T2 and T8. |

| 11 | 39 | Male | Hispanic man involved in a MVA. Findings included atlanto-occipital dislocation with stretching of the spinal cord. C7, T11 and L1 fractures and mild multiple contusion at C8, slight subarachnoid hemorraghes of the ventral sulcus at T2, distortion of the ventral tract at T11. |

| 12 | 29 | Male | Decedent suffered multiple gunshot wounds, including one that penetrated the spinal canal and lacerated the spinal cord at C7. Laceration at C7 was associated with myelopathic changes from C5 to T1 (white matter fragmentation, hemorrhage and edema). |

| 13 | 35 | Male | Caucasian shot multiple times. One bullet penetrated the T9 vertebra in a dorsoventral direction. Injury was contusive from T7 to T12 with the epicenter at T9-T10. Petechial hemorrhages in the gray and white matter with focal subarachnoid and subpial hemorrhages. |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to RWK (NIH Grant NINDS 1RO1NS59836 and Craig Neilsen Foundation grant 221346) and The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis. We thank Dr. Michael D. Norenberg and Dr. Alex Marcillo for their expertise with the Human Spinal Cord sections, Dr. Marine Dididze for obtaining the CSF samples from SCI patients, and the SCI core facility at the Miami Project to Cure Paralysis.

REFERENCES

- Adamczak S, Dale G, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Bullock MR, Dietrich WD, Keane RW. Inflammasome proteins in cerebrospinal fluid of brain-injured patients as biomarkers of functional outcome: clinical article. Journal of neurosurgery. 2012;117:1119–1125. doi: 10.3171/2012.9.JNS12815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamczak SE, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Dale G, Brand FJ, 3rd, Nonner D, Bullock MR, Dahl GP, Dietrich WD, Keane RW. Pyroptotic neuronal cell death mediated by the AIM2 inflammasome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:621–629. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Yin H, Betts C, Lakhal S, Wood MJ. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie MS, Hermann GE, Rogers RC, Bresnahan JC. Cell death in models of spinal cord injury. Progress in brain research. 2002;137:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)37006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Hong JS. Microglia and inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration: multiple triggers with a common mechanism. Progress in neurobiology. 2005;76:77–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett H, Dietrich WD., 3rd Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury: Current Status of Potential Mechanisms of Injury and Neurologic Outcomes. J Neurotrauma. 2014 doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Pathophysiology of cerebral ischemia and brain trauma: similarities and differences. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:133–150. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000111614.19196.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivet M, Hemming F, Pernet-Gallay K, Fraboulet S, Sadoul R. Emerging role of neuronal exosomes in the central nervous system. Frontiers in physiology. 2012;3:145. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton A. Cancer cells use exosomes as tools to manipulate immunity and the microenvironment. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:78–80. doi: 10.4161/onci.1.1.17826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rivero Vaccari JP, Lotocki G, Alonso OF, Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD, Keane RW. Therapeutic neutralization of the NLRP1 inflammasome reduces the innate immune response and improves histopathology after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1251–1261. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rivero Vaccari JP, Lotocki G, Marcillo AE, Dietrich WD, Keane RW. A molecular platform in neurons regulates inflammation after spinal cord injury. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:3404–3414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0157-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFazio MV, Rammo RA, Robles JR, Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD, Bullock MR. The potential utility of blood-derived biochemical markers as indicators of early clinical trends following severe traumatic brain injury. World neurosurgery. 2014;81:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Arrastia R, Wang KK, Papa L, et al. Acute biomarkers of traumatic brain injury: relationship between plasma levels of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 and glial fibrillary acidic protein. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:19–25. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends in neurosciences. 1999;22:391–397. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou E, Melachroinou K, Roumeliotis T, Garbis SD, Ntzouni M, Margaritis LH, Stefanis L, Vekrellis K. Cell-produced alpha-synuclein is secreted in a calcium-dependent manner by exosomes and impacts neuronal survival. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:6838–6851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5699-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fevrier B, Vilette D, Archer F, Loew D, Faigle W, Vidal M, Laude H, Raposo G. Cells release prions in association with exosomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:9683–9688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308413101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figley SA, Khosravi R, Legasto JM, Tseng YF, Fehlings MG. Characterization of vascular disruption and blood-spinal cord barrier permeability following traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:541–552. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipazzi P, Burdek M, Villa A, Rivoltini L, Huber V. Recent advances on the role of tumor exosomes in immunosuppression and disease progression. Seminars in cancer biology. 2012;22:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JC, Norenberg MD, Ramsay DA, Dekaban GA, Marcillo AE, Saenz AD, Pasquale-Styles M, Dietrich WD, Weaver LC. The cellular inflammatory response in human spinal cords after injury. Brain. 2006;129:3249–3269. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde CT, Karri SK, Young AM, Ogilvy CS. Predictive markers in traumatic brain injury: opportunities for a serum biosignature. British journal of neurosurgery. 2014;28:8–15. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2013.815317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhbeis C, Frohlich D, Kuo WP, et al. Neurotransmitter-triggered transfer of exosomes mediates oligodendrocyte-neuron communication. PLoS biology. 2013;11:e1001604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes C, Keller S, Altevogt P, Costa J. Evidence for secretion of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase via exosomes from a cell model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroscience letters. 2007;428:43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haneklaus M, O'Neill LA, Coll RC. Modulatory mechanisms controlling the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammation: recent developments. Current opinion in immunology. 2013;25:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington MG, Fonteh AN, Oborina E, et al. The morphology and biochemistry of nanostructures provide evidence for synthesis and signaling functions in human cerebrospinal fluid. Cerebrospinal fluid research. 2009;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson PJ, O'Connell MT, Rothwell NJ, et al. Inflammation in human brain injury: intracerebral concentrations of IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, and their endogenous inhibitor IL-1ra. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1545–1557. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane RW, Kraydieh S, Lotocki G, Bethea JR, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Dietrich WD. Apoptotic and anti-apoptotic mechanisms following spinal cord injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2001;60:422–429. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.5.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotocki G, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Perez ER, Sanchez-Molano J, Furones-Alonso O, Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Alterations in blood-brain barrier permeability to large and small molecules and leukocyte accumulation after traumatic brain injury: effects of post-traumatic hypothermia. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1123–1134. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas SM, Rothwell NJ, Gibson RM. The role of inflammation in CNS injury and disease. British journal of pharmacology. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S232–240. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant S, Hilton H, Burczynski ME. The multifaceted exosome: biogenesis, role in normal and aberrant cellular function, and frontiers for pharmacological and biomarker opportunities. Biochemical pharmacology. 2012;83:1484–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa L, Robertson CS, Wang KK, et al. Biomarkers Improve Clinical Outcome Predictors of Mortality Following Non-Penetrating Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurocritical care. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s12028-014-0028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovich PG. Immunological regulation of neuronal degeneration and regeneration in the injured spinal cord. Progress in brain research. 2000;128:43–58. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)28006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouw MH, Kwon BK, Verbeek MM, et al. Structural biomarkers in the cerebrospinal fluid within 24 h after a traumatic spinal cord injury: a descriptive analysis of 16 subjects. Spinal cord. 2014;52:428–433. doi: 10.1038/sc.2014.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Franchi L, Nunez G, Dubyak GR. Nonclassical IL-1 beta secretion stimulated by P2X7 receptors is dependent on inflammasome activation and correlated with exosome release in murine macrophages. Journal of immunology. 2007;179:1913–1925. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran L, Honsho M, Zahn TR, Keller P, Geiger KD, Verkade P, Simons K. Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid peptides are released in association with exosomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:11172–11177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603838103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saman S, Kim W, Raya M, et al. Exosome-associated tau is secreted in tauopathy models and is selectively phosphorylated in cerebrospinal fluid in early Alzheimer disease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:3842–3849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street JM, Barran PE, Mackay CL, Weidt S, Balmforth C, Walsh TS, Chalmers RT, Webb DJ, Dear JW. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of translational medicine. 2012;10:5. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. Exosomes/microvesicles: mediators of cancer-associated immunosuppressive microenvironments. Seminars in immunopathology. 2011;33:441–454. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thery C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2009;9:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Niel G, Porto-Carreiro I, Simoes S, Raposo G. Exosomes: a common pathway for a specialized function. Journal of biochemistry. 2006;140:13–21. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viaud S, Thery C, Ploix S, Tursz T, Lapierre V, Lantz O, Zitvogel L, Chaput N. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes for cancer immunotherapy: what's next? Cancer research. 2010;70:1281–1285. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori S, Zhang Z, Moghieb A, et al. Acute Diagnostic Biomarkers for Spinal Cord Injury: Review of the Literature and Preliminary Research Report. World neurosurgery. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]