Abstract

Evidence for effective treatment for behavioral problems continues to grow, yet evidence about the effective mechanisms underlying those interventions has lagged behind. The Stop Now and Plan (SNAP) program is a multicomponent intervention for boys between 6 and 11. This study tested putative treatment mechanisms using data from 252 boys in a randomized controlled trial of SNAP versus treatment as usual. SNAP includes a 3 month group treatment period followed by individualized intervention, which persisted through the 15 month study period. Measures were administered in four waves: at baseline and at 3, 9 and 15 months after baseline. A hierarchical linear modeling strategy was used. SNAP was associated with improved problem-solving skills, prosocial behavior, emotion regulation skills, and reduced parental stress. Prosocial behavior, emotion regulation skills and reduced parental stress partially mediated improvements in child aggression. Improved emotion regulation skills partially mediated treatment-related child anxious-depressed outcomes. Improvements in parenting behaviors did not differ between treatment conditions. The results suggest that independent processes may drive affective and behavioral outcomes, with some specificity regarding the mechanisms related to differing treatment outcomes.

Keywords: cognitive behavioral treatment, mechanisms, aggression, anxiety, depression

The establishment of sound and replicable models of intervention for children’s behavioral problems should remain a priority. Practitioners and administrators benefit from being able to select from an array of evidence-based treatment models to meet varying needs within their community. Additionally, demonstrating that broad forms of intervention (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT) are more effective than others helps to choose between possible alternatives. At the same time, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms within established models that are most associated with desirable outcomes. Doing so helps to make intervention efforts more efficient, and refinements of intervention models can be made with some knowledge about integral elements. Understanding which mechanisms are fundamental to treatment may also provide information about key etiological factors involved in the onset or maintenance of disorders.

Interest in the identification of mechanisms of treatment is not novel. Clinical researchers and theorists have called for a greater focus on this subject for several decades, and it remains the case that the literature base contains insufficient evidence to determine which processes are activated by therapies in order to affect change (e.g., Kazdin, 2011; La Greca, Silverman & Lochman, 2009). For example, a meta-analysis of interventions in juvenile justice settings (Landenberger & Lipsey, 2005) found that, among other factors, interventions that included CBT-based components designed to enhance interpersonal problem solving and to promote anger regulation skill development were particularly associated with improved outcomes. In fact, accounting for the individual factors or putative mechanisms of treatment resulted in there being no remaining differences between particular intervention models (Landenberger & Lipsey, 2005).

The SNAP (Stop Now and Plan) intervention model (Augimeri, Farrington, Koegl, & Day, 2007) was developed to capitalize on empirically established treatment elements. It is a structured and manualized multi-component intervention model that incorporates CBT principles throughout. It includes components of in-group treatment activities for children and parents, and addresses individualized needs through components such as individual mentoring, family therapy sessions, homework help, and other similarly targeted treatment components. The program was originally developed with a primary focus on reducing antisocial behavior, but has also shown effectiveness in reducing children’s affective difficulties (Augimeri et al., 2007; Augimeri, Jiang, Kogel, & Carey, 2006; Koegl, Farrington, Augimeri, & Day, 2008).

The SNAP logic model identifies, among the presumed mechanisms of treatment effect, problem solving skills training, emotion regulation skills training, and social skills training. Regarding problem solving, for example, children are taught to consider potential behaviors in response to a particular dilemma, and are taught to evaluate whether a given solution might make their problems bigger or smaller. They are instructed to develop solutions that do not hurt others. Children are also exposed to the problem solving strategies of others. Using role plays, vignette discussions and videotape reviews, children critique one another’s solutions to problems and have the opportunity to observe and reflect upon their own problem-solving efforts.

SNAP teaches emotion regulation skills, including a focus on recognizing cues related to negative affect and working to interrupt the process before responding out of anger or frustration. Children are provided with techniques to help redirect themselves, relax and calm themselves, and engage in more mindful solutions. The SNAP model targets social skills development by capitalizing on the group-based format. Under careful guidance from group leaders, children engage in role plays, provide critiques and feedback to one another, help one another to develop productive solutions to problems, and engage in modeling of desirable behavior.

In addition, parent management training is a common component of effective treatment models for behavioral disorders in youth (Chorpita et al., 2011; Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008). The SNAP model provides parenting skills development activities through the use of group sessions with other parents, in which parents discuss dilemmas and concerns and are led in the use of SNAP techniques to address challenging child behavior. Parents not only learn through observation and modeling, but they have the opportunity to discuss their frustrations with other parents who may be experiencing similar difficulties with their children. After group sessions are completed, parents may be provided with additional SNAP parenting booster sessions on an individualized, as-needed basis. These components of the SNAP program are intended to both convey information about appropriate and productive parenting behaviors to employ with children as well as to provide parents with resources to manage their own affective experiences and help parents cope with the stress of problematic child behaviors.

As noted, these treatment components are not unique to SNAP. Parent behavioral training is a core component of many effective intervention strategies, such as parent management training (PMT). These strategies typically focus on the use of behavioral principles to reinforce desirable and compliant behavior and to eliminate undesirable and antisocial behaviors. PMT is often paired with another well-established intervention, problem-solving skills training, or PSST, and problem-solving skills development is a common element in many other treatment models. As with SNAP, problem-solving skills intervention components typically involve working with the child to evaluate multiple solutions to problems and to consider the consequences of varying options. Efforts to improve interpersonal skills are also often included in treatment models (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009; Spence, 2003), with the recognition that many of children’s antisocial behaviors emerge from problematic interactions with peers. Landenberger & Lipsey’s (2005) meta-analysis, as noted previously, also found support for the use of problem-solving skills and anger control components of behavioral interventions in juvenile justice populations. However, they did not find support for the effectiveness of social skills training components.

Prior studies have examined similar constructs as putative mediators of treatment outcome. For example, Lochman & Wells (2002) identified treatment related changes in parenting practices and in social cognition, particularly hostile attributional bias, and found some evidence suggesting that they mediated outcomes. However, they also demonstrated that therapeutic mechanisms may vary in their effects on differing outcomes (e.g., delinquency versus school behavior). Changes in parenting behaviors have been identified in several studies as mediators of treatment outcomes (e.g., Dishion, Patterson & Kavanagh, 1992; Henggeler et al., 2009; Patterson & Forgatch, 1995). In a randomized controlled trial for treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Hinshaw (2002) found evidence for the effects of parenting behaviors on behavioral outcomes, but did not find differences between treatment conditions on parenting behaviors.

Efforts to identify mechanisms of treatment effects for children with behavioral problems are complicated by two issues. First, behavioral problems are heterogeneous and multiply determined (e.g., Burke, Loeber & Birmaher, 2002), even within distinct diagnostic constructs such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD). Relatedly, behavioral problems show a high level of comorbidity with depression and anxiety (Angold, Costello & Erkanli, 1999). In particular, evidence supports separate affective and behavioral dimensions of symptoms within ODD (Burke et al., 2014). Given this, it should perhaps not be surprising to find that behaviorally-oriented interventions like SNAP influence affective functioning as well. Additionally, it does not seem likely that any single mechanism will sufficiently explain the outcomes associated with interventions for these problems. There remains a great level of need regarding evidence as to how these interventions affect outcomes, and whether there are general treatment effects across outcomes, or specific treatment effects on particular mechanisms, which in turn influence particular outcomes.

As part of a structure set of planned analyses, the present paper uses the same sample and data as a prior publication that detailed treatment-related outcomes associated with SNAP (Burke & Loeber, in press). This project was the first large-scale, random controlled trial of SNAP conducted independently of the developers of the SNAP intervention model. Data was collected from one of a small number of implementations of the SNAP progroutside of Canada. Participants (n=252) were randomly assigned to receive SNAP services or to receive standard treatment as usual in the community.

The first set of analyses (Burke & Loeber, in press) provided a comprehensive assessment of outcomes on measures of ODD, CD, ADHD, depression and anxiety, including both continuous (Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL); Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and symptom count (Child Symptom Inventory (CSI); Gadow & Sprafkin, 1994) measures. Significant effects favoring SNAP were identified for CBCL outcomes of Aggressive Behavior, Conduct Problems, Externalizing, Internalizing, Withdrawn-Depressed and Anxious Depressed. Additionally, significant CSI-based symptom count reductions favoring SNAP were found for ADHD, ODD, depression and separation anxiety.

As noted above, the literature on treatments for behavioral problems has identified problem-solving skills, emotional regulation skills, social skills development, and parenting skills as particularly relevant treatment components. Since these are also described as key components of the SNAP model, the present analyses were planned during the development of the project in order to test putative treatment mechanisms as identified by the developers of the SNAP program. Specifically, these analyses will test four mechanisms that follow from the literature base: 1) problem solving skills, 2) prosocial behaviors, 3) emotion regulation skills, 4) parenting behaviors, and 5) parental stress.

We selected two CBCL-measured outcomes from among the available outcomes (see Burke & Loeber, in press) to be tested in mediational models. This selection was driven by a desire to present a focused analysis rather than a comprehensive and potentially unwieldy consideration of many outcomes. We also selected outcomes with the intent of testing whether putative mechanisms of treatment would be equally associated with changes in markedly varying types of outcomes. Finally, we were interested in considering comparatively circumscribed outcomes rather than the broader externalizing or internalizing constructs. A primary focus of the SNAP program is to reduce serious behavioral problems; we selected the Aggressive Behavior subscale over Rule Breaking as an index of serious behavioral problems. To consider a contrasting alternative from among the internalizing subscales, we chose to test the Anxious-Depressed subscale over Somatic Complaints or Withdrawn-Depressed.

We hypothesized that problem solving skills, prosocial behaviors, emotion regulation skills, parenting behaviors and parental stress will be enhanced by SNAP treatment participation relative to standard services as usual in the community (STND), and that these in turn would predict improvements across both types of outcomes. We predicted that tests of mediation will reveal significant mediation of treatment group effects on outcomes for each of the aforementioned mechanisms. However, due to the heterogeneous and multiply determined nature of these outcomes, we did not anticipate observing any instances of full mediation.

Method

Sample

Parents calling for services at the two SNAP-providing agencies in the region were informed about the study (N = 481). Any parents expressing interest were informed that study participation would involve a random chance of participating in SNAP or standard services (STND). After being given basic information about the study, approximately 30% of parents (n = 144) declined further contact regarding the study. The most common reasons for doing so were an unwillingness to be randomly assigned to treatment other than SNAP, or already being involved in other behavioral health services for the child. Of those interested in learning more about the study, 34 declined participation, 25 were not eligible, and 26 were lost to further contact. Of the 252 enrolled into the study, randomization resulted in 130 boys participating in SNAP and 122 in standard services. Study participation at the 3, 9 and 15 month interview waves was 89.2% (n = 116), 80.0% (n = 104), and 84.6% (n = 110), respectively, in the SNAP condition, and 89.3% (n = 122), 83.6% (n = 109) and 82.8% (n = 101), respectively, in the STND condition.

In order to avoid interfering with the clinical needs of children in the study, the only restriction placed on participants regarding services, subsequent to assignment to condition, was that children in SNAP could not receive the most intensive community-based service (wraparound) and conversely, those in the STND service condition could not participate in SNAP.

Eligibility

Children had to have a qualifying behavioral score via parent report (CBCL) or teacher report (Teacher Report Form; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) of Aggressive Behavior (T score greater than or equal to 70), Rule Breaking (70), DSM Conduct Problems (70) or Externalizing Behavior (T score greater than or equal to 64).

Random assignment

Upon signing consent and meeting eligibility requirements, participants were randomly assigned to study condition. Randomization was performed by the study investigators independently of the treatment providers using a random number generating computer program. As an intent-to-treat study, once assigned to condition, participants remained in the study, regardless of their actual level of participation in the treatment to which they were assigned.

At the time of the initiation of the study, only the SNAP for Boys version of the SNAP program was provided in the region. As a result, only boys could be enrolled in the study. Half the sample (50%) reported a household income of $14,999 or less; 14% reported an income above $33,201. Three-quarters of parents identified their child as African American, 13% as White, and 10% using more than one racial category. Parent participants were almost exclusively female; in only 14 cases was the parental informant male. The mean age of the boys was 8.5 (SD = 1.8) years of age; boys ranged from 6.0 to 12.8 years at baseline. Estimated IQ ranged from 60 to 128; the average was 91.6 (SD = 12.5). There were 38 participants (14.7%) who had parent-reported police contact due to the youth’s behavior. Of the total sample, 82.9% (n = 175) were non-siblings, and 17.1% (n = 77) were siblings, in 36 sibling clusters. There were 41 siblings in SNAP and 36 siblings in STND; the difference was not significant (χ2 = .12, p = .72). Analyses accounted for nested observations among siblings.

SNAP Treatment

SNAP includes several distinct treatment components. First, during the initial 12 week period, separate parent and child group-based modules are provided on a weekly basis. Groups for parents and children are conducted simultaneously. SNAP children’s groups adhere closely to a manual in order to provide consistent and structured content. Each group session moves through a sequence of activities, and addresses a specific topic for the week, such as stealing, coping with anger, and managing group pressure. Children are taught cognitive and behavioral skills and are given structured practice experiences, observation of others and rehearsal to apply these skills to specific circumstances. Each group session makes significant use of structured elements of role-play, problem-solving and peer feedback to evaluate alternative solutions. Children are helped to evaluate whether the solutions that they generate for various problems will lead to improved or to poorer outcomes. During parent groups, parents are led in psychoeducational content, and discuss with other parents their use of parenting strategies and their efforts at coping with their own emotional reactions. Parent group content is also manualized and incorporates SNAP principles.

Upon completion of group sessions, after 12 weeks, each child is re-assessed to determine where clinical needs continue. SNAP treatment at this point is individualized; SNAP providers select from established treatment modules to address a child and family’s specific needs. Modules include individualized SNAP family counseling sessions, SNAP booster sessions, a mentoring component, school advocacy, academic tutoring, a victim restitution module, crisis counseling and a fire-setting component. A leadership module provides children who have been successful in the program an opportunity to provide peer mentoring. There is no set duration for this portion of SNAP treatment; it is provided as long as clinical needs remain for a particular child or family.

SNAP service use

Children in the SNAP condition attended an average of 6.25 (SD = 4.3) of the 12 child sessions, and parents attended an average of 5.02 (SD = 4.2) of the 12 parent sessions. Of the 130 children assigned to SNAP, there were 30 children (23.1%) who attended no child SNAP groups and 37 parents (28.5%) who attended no parent SNAP groups.

Subsequent to participating in the group treatment component of SNAP, youth received individual SNAP components as determined by protocol. Of all families in SNAP, 70.0% received at least one component; the maximum number of different components used was four. The most common was individualized SNAP family counseling sessions, which was provided to 68 participants (52% of the SNAP group), who received an average of 4.12 (SD = 6.9) sessions. The mentoring component was provided to 64 participants (49%), who received a mean of 2.5 (SD = 4.2) units. School advocacy was used by 23 (18%) participants, who received between 0 and 11 units, mean = 0.43 (SD = 1.35). Other SNAP components used by fewer than 10% of the SNAP families included academic tutoring, crisis counseling, and the leadership module.

Standard services treatment

Children assigned to the STND condition were provided with referral information for treatment providers in their vicinity. For each child in standard services, study staff worked to coordinate contact with wraparound service providers in order to ensure that each participant in the STND condition had the opportunity to receive the most intensive level of community-based services for severe behavioral problems available in the region. However, families were not required to participate in wraparound services; nor was it guaranteed that community providers would agree that the requisite level of need existed for that level of service.

Approximately half (53%) of those in the STND group engaged in behavioral health services, either from wraparound providers, specialty behavioral health service providers or school-based behavioral or emotional services. Regarding wraparound specifically, 43 standard service participants (35%) participated in wrap services at some point. At baseline, 17% of youth in each condition were involved in other behavioral health services, and during waves 2 through 4, 23% of youth in each condition were involved in any such services. Regarding school-based services for behavioral or emotional problems, more youth in STND than SNAP were involved in such services at baseline (40% vs. 21%). Over waves 2 through 4, 36% of youth in SNAP and 31% of youth in STND were involved in school-based services.

Data collection

Parents and children were interviewed in 4 waves: at baseline, prior to randomization, and then again at 3 months, 9 months and 15 months after baseline. An assessment wave was conducted at 3 months because the SNAP program begins with 3 months of group sessions prior to delivering individualized treatment options. Subsequent assessment waves occurred at 9 and 15 months past baseline to reflect periods of 6 months and 1 year after the end of the group session portion of SNAP. Interviews were administered using a laptop computer by trained research interviewers. Participants were compensated for participating. Interviews were usually conducted in family homes, although office interviews and alternate locations were employed at family request. Informed consent to participate was obtained from all parents, and assent was obtained from all children in the study. All study procedures were approved and monitored by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Outcomes

Parent report on the CBCL was obtained at each wave. Outcomes used in this study were the T-scores on the Aggression and Anxious-Depressed subscales. The Aggression subscale consists of 18 items relating to aggressive behavior, such as being mean, destroying others things, and getting in fights. Reliability alpha at baseline was .77 for the Aggression scale. There was no baseline difference on Aggression between SNAP (M = 79.1, SD = 9.6), and STND (M = 79.3, SD = 9.5). Items on the Anxious-Depressed subscale tap behaviors such as crying a lot, being fearful or nervous, and feeling unloved or worthless. At baseline, reliability alpha was .71 for Anxious-Depressed, and there was no significant difference at baseline between SNAP (M = 62.7, SD = 8.6) and STND (M = 62.9, SD = 9.1), on the scale.

Problem solving

Children were administered the Outcome Expectations Questionnaire (OEQ; Pardini, Lochman, & Frick, 2003) as an index of problem solving. This version of the OEQ (Perry, Perry, & Rasmussen, 1986) includes eight brief vignettes which elicit children’s expectations about the outcomes of aggressive behavior against a peer. In response to each vignette, participants are asked to rate the likelihood that various outcomes will occur on a four-point scale (from 1, or very sure the outcome will not occur to 4, or very sure that the outcome will occur. For the purposes of the current study, only the items measuring expectations for Remorse, Punishment, and Victim Suffering due to aggressive behaviors were used. The mean scores at baseline for these constructs were 12.18 (SD = 8.5), 16.31 (SD = 6.9), and 17.49 (SD = 6.1), respectively.

Prosocial behaviors and emotion regulation skills

The Social Competence Scale - Parent Version is a 12-item measure created for the Fast Track Project (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995). The scale includes two subscales; one assesses the child’s prosocial behaviors and the second measures emotional regulation skills. Response options were on a five point scale from not at all to very well. The Prosocial Behaviors construct consisted of six items measuring how well the child resolved problems on his own, listened to others point of view, or was helpful to others. Reliability alpha at baseline for this construct was .79; the mean score at baseline was 8.38 (SD = 4.2). The six Emotion Regulation Skills items measured how well the child did at things like coping with failure or controlling temper during disagreements. Reliability alpha at baseline was .71, and the mean was 5.12 (SD = 3.3).

Parenting behaviors

The Parenting Practices Inventory (PPI; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2001) is a 72-item questionnaire used to assess the disciplinary style of a parent or caregiver, with parents responding to items rated on a 7 point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Four subscales from the measure were used in this study: Harsh Discipline, Inconsistent Discipline, Positive Parenting, and Clear Expectations.

Harsh Discipline included 15 items measuring how often parents scold or yell, or spank, slap or hit the child for misbehavior. At baseline in the present study, the scale showed good reliability (alpha = .91), with a mean of 28.51 (SD =13.4). Inconsistent Discipline consists of 6 items measuring how often the parent initiates but gives up on disciplinary efforts, how often the child gets away with misbehavior, or how often disciplinary efforts depend on the parent’s mood. At baseline, reliability was .87 in the present study (M = 11.2, SD = 5.4). Positive Parenting includes 15 items relating to the frequency with which parents praise the child, given hugs, or give extra privileges for desirable behavior. In the present study, the reliability of the scale was .93 at baseline (M = 48.79, SD = 11.6). Clear Expectations include 3 items measuring the parents’ estimation of how clear are the rules or expectations they have set for the child. Reliability at baseline was .88 (M = 14.07, SD = 4.3).

Parental stress

The Parenting Stress Index- Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, 1995) was used to measure self-reported parental stress. This 36-item measure yields a total index measuring the amount of stress the parent is feeling, and includes three subscales. In the present study, constructs reflecting the three subscales were used as potential mechanisms of treatment outcomes. Parental Distress included 12 items reflecting stress due to personal factors, including impaired parenting competence. At baseline, reliability for this scale was .94 (M = 30.5, SD = 10.1). Parent-child Dysfunctional Interaction includes 12 items measuring the parent’s perception of their interactions with the child, and whether those are reinforcing or negative, rejecting experiences for the parent. Reliability at baseline was .95 for this scale (M = 27.08, SD = 9.4). The Difficult Child scale included 12 items reflecting stress due to difficulty managing the child’s behaviors, non-compliance or defiance. This subscale had a reliability alpha of .91 at baseline (M = 36.0, SD = 8.6).

Statistical Analyses

Since participants in the SNAP treatment condition participated in groups, while those in STND participated in individualized treatment, the study design is partially nested (Bauer, Sterba, & Hallfors, 2008). However, there was no significant variation associated with participation in a specific treatment group; the ICC for treatment group for Aggression was .006, 95% confidence interval (CI) [.000, .065], and for Anxious-Depressed scores was .000, 95% CI [.000, .020]. As a result, the present analyses do not include clustering at the level of groups within treatment condition.

In the present data, youth were also nested in sibling clusters, and observations by wave were nested within individual participants. A hierarchical linear modeling strategy was used to model clustering at these two levels. Wave was coded as 0, 3, 9, and 15 to represent months from baseline, in order to account for the shorter duration between baseline and the first assessment point (3 months) relative to the remaining assessment points. It should also be noted that the SNAP group treatment occurred between the baseline and 3 month time point, while individualized treatment occurred for those in the SNAP group for the remainder of the study. Normal distributions of outcomes were modeled. Analyses were conducted using Stata (StataCorp, 2009).

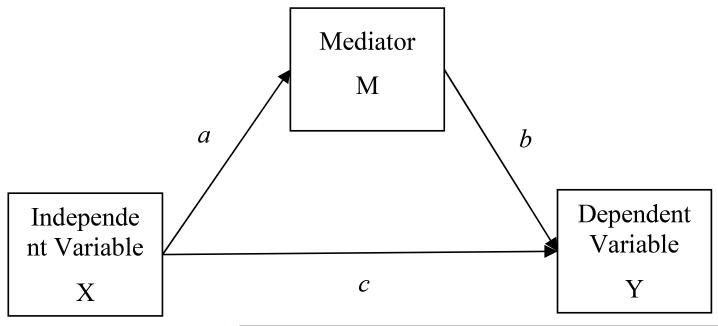

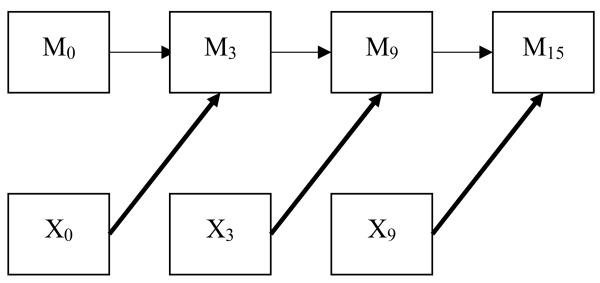

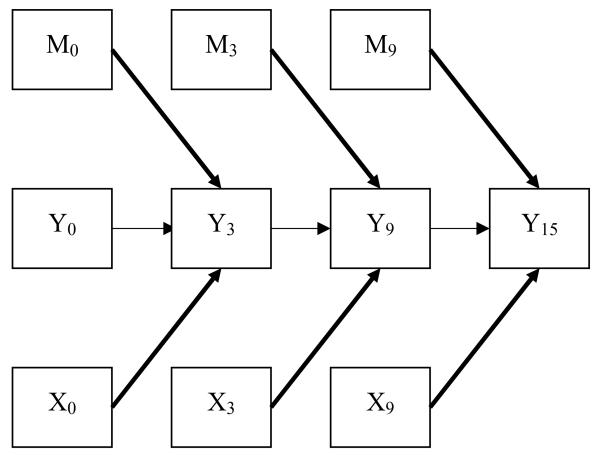

Figure 1 shows a simple mediation model. Whether a particular time-varying factor (e.g., emotion regulation) might be considered a mechanism of treatment would depend on whether it was influenced by the treatment (the independent variable; path a in Figure 1) and whether it in turn influenced a particular outcome of interest (e.g., aggressive behavior; path b in Figure 1). We used a strategy for testing mediation (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001) adapted for longitudinal data. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the modeling strategy that was used to obtain the parameter values to estimate paths a, b and c’ in these analyses. We lagged values for the mediating variable by one observation period, so that prediction from the mediating variable to the outcome (path b) represented the relationship over time. In addition, we introduced the value of the outcome variable at the preceding time point as a control so that the prediction from the putative mediator to the outcome represented change in the outcome from one time point to the next (e.g., Duckworth, Tsukayama, & May, 2010). Since consistent mediation requires that the predictor significantly predicts both the outcome (path c) and the mediator (path a), we began by identifying those potential mediators that were significantly differentiated (path a) by treatment group membership.

Figure 1.

The simple mediational model.

Figure 2.

Modeling mediational path a using the fixed effect for treatment condition (X) predicting each measure of the mediator (M) in a longitudinal multilevel model. Subscripts represent the month at which measures were taken from baseline at month 0. The stability and cross-lagged paths are represented by a single parameter estimate each in the models. Fixed effects for age and assessment month were also included in each model.

Figure 3.

Modeling mediational paths b and c’ in a longitudinal multilevel model. The coefficient for the mediational path b reflects the fixed effect of the prediction from each measurement of the mediator (M) to each outcome (Y). c’ is the fixed effect of treatment condition (X) predicting outcome (Y). Subscripts represent the month at which measures were taken from baseline at month 0. The stability and cross-lagged paths are represented by a single parameter estimate each in the models. Fixed effects for age and assessment month were also included in each model.

Missing data

Multilevel modeling is flexible regarding missing data, and the present analyses used maximum likelihood estimators for each model, which provide advantages in handling missing data (Allison, 2012). To further evaluate the effect of missing data on estimates in the present analyses, multiple imputation models were tested imputing values for Aggression (StataCorp, 2009). There were no meaningful differences in comparison to models with missing data. As a result, the analyses presented here did not employ multiple imputation.

Results

Aggression and Anxious-Depressed Outcomes

The effect of SNAP treatment on behavioral and affective outcomes as measured by the CBCL has been previously reported (Burke & Loeber, in press). SNAP was associated with significantly better outcomes in comparison to STND across multiple indicators of child behavioral and affective problems, including Aggression and Anxious-Depressed behaviors. The modeling strategy employed in the prior analyses of treatment outcomes (Burke & Loeber, in press) was slightly different than that employed here. In those analyses, a random effect for individual child’s slope was modeled. The present analyses include the prior wave measurement of each outcome as a fixed effect. This modeling strategy yielded the following for SNAP treatment in contrast to STND for child Aggression, B = −2.24, SE = 0.84, p = .008, 95% CI [−3.89, −0.58], and for child Anxious-Depressed scores, B = −1.50, SE = 0.50, p = .003, 95% CI [−2.49, −0.52], which vary slightly from the previous report due to the aforementioned modeling strategy differences.

To examine whether changes in children’s Aggression and Anxious-Depressed scores were predicted by each of the other outcomes being tested here, separate models were tested for each as a predictor of each other outcome at waves 2 through 4, controlling for the outcome itself in the preceding wave. These outcomes changed independently of one another: Aggression did not predict changes in Anxious-Depressed scores, B = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p = .15, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.08. Similarly, Anxious-Depressed scores did not predict changes in Aggression, B = −0.01, SE = 0.05, p = .91, 95% CI [−0.10, 0.09].

Potential Mechanisms of Treatment

To most efficiently evaluate the selected variables as potential mechanisms of SNAP treatment, we first identified those that significantly differed by treatment condition. In each model, the value of the outcome at the preceding wave was included as a predictor. The results are shown in Table 1. Youth in SNAP showed higher levels of each indicator of problem solving skills: they anticipated higher levels of punishment, remorse and victim suffering as a result of engaging in undesirable behavior. They showed higher levels of social competence in terms of both prosocial behaviors and in emotion regulation skills. There were no observed differences between SNAP and STND youth on measures of parenting behaviors, but there was a trend towards higher levels of positive parenting behaviors for SNAP. As a result, this variable was retained for further testing as a potential mechanism, while harsh parenting, inconsistent parenting, and consistent use of clear expectations were not. Among indicators of parental stress, only the difficult child subscale differed between SNAP and STND children, while the subscales of parental distress and parent-child dysfunctional interaction did not.

Table 1.

Testing for treatment group differences in potential mechanism at waves 2 through 4.

| Mechanism | B | SE | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Solving Skills | |||||

| Punishment | 2.42 | 0.64 | <.001 | 1.17 | 3.66 |

| Remorse | 2.73 | 0.91 | .003 | 0.95 | 4.52 |

| Victim Suffering | 1.89 | 0.70 | .007 | 0.52 | 3.26 |

| Prosocial Behaviors | 1.56 | 0.56 | .005 | 0.46 | 2.66 |

| Emotion Regulation Skills | 1.28 | 0.48 | .007 | 0.34 | 2.22 |

| Parenting Behaviors | |||||

| Harsh | −2.38 | 1.53 | .12 | −5.38 | 0.62 |

| Inconsistent | −0.66 | 0.62 | .28 | −1.87 | 0.55 |

| Positive | 2.42 | 1.44 | .09 | −0.40 | 5.24 |

| Clear Expectations | 0.45 | 0.46 | .32 | −0.45 | 1.35 |

| Parental Stress | |||||

| Difficult Child | −2.40 | 1.13 | .03 | −4.61 | −0.18 |

| Parental Distress | −1.30 | 1.30 | .32 | −3.86 | 1.25 |

| Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction | −1.15 | 1.17 | .33 | −3.44 | 1.15 |

Note: Values of each outcome at the preceding wave were included as predictors in each model, as were values for wave and age. The beta coefficient for each outcome is the difference between SNAP and treatment as usual on scores for the specified putative mechanism. These represent tests of path a in Figure 1.

Mechanisms as predictors of Aggression

Those variables identified as significantly different between SNAP and STND children were each tested as predictors of Aggression in the following assessment wave. Age, wave, treatment condition and level of Aggression in the preceding wave were all included as predictors in each model. Table 2 shows the coefficient associated with the potential mechanism of treatment as a predictor of Aggression in each model.

Table 2.

Selected putative SNAP mechanisms predicting Aggression.

| Mechanism | B | SE | P | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Solving Skills | |||||

| Punishment | −0.01 | 0.06 | .92 | −0.13 | 0.12 |

| Remorse | −0.03 | 0.05 | .53 | −0.12 | 0.06 |

| Victim Suffering | −0.00 | 0.06 | .92 | −0.11 | 0.12 |

| Prosocial Behaviors | −0.23 | 0.09 | .01 | −0.41 | −0.05 |

| Emotion Regulation Skills | −0.35 | 0.11 | .001 | −0.56 | −0.14 |

| Parenting Behaviors | |||||

| Positive | −0.08 | 0.03 | .015 | −0.15 | −0.02 |

| Parental Stress | |||||

| Difficult Child | 0.11 | 0.05 | .031 | 0.01 | 0.21 |

Note: Values of each outcome at the preceding wave were included as predictors in each model, as were values for wave and age. The beta coefficient for each row is the value of each unit increase in aggressive behavior for each unit increase in the specified putative mechanism. These represent tests of path b in Figure 1.

As is evident, none of the indicators of problem-solving skills predicted changes in aggressive behavior. Each of the scales related to social competence, on the other hand, namely prosocial behaviors and emotion regulation skills, significantly predicted changes in Aggression. Changes in Aggression were also predicted by positive parenting, and by parental stress associated with difficult child behavior.

Four constructs were potential mediators of the effect of SNAP on Aggression, given that the treatment condition significantly differentiated aggressive behavior scores over time (path a) and that the variable predicted change in aggressive behavior (path b). The mediation effect was tested by multiplying the mediator coefficient (path b) and the coefficient for the independent variable (path a). Using the joint significance test (McKinnon, 2008), the presence of both a significant path a and path b indicates a significant indirect effect. This means that significant indirect effects predicting Aggression include prosocial behavior, emotional regulation skills, and parental stress: difficult child. In each case, treatment group remained a significant predictor of aggressive behavior, suggesting that the mediating effect in each case was partial, rather than full.

Mechanisms as predictors of Anxious-Depressed scores

Each of the putative mechanisms that had been shown to differ by treatment group were tested as predictors of Anxious-Depressed scores. Age, wave, treatment condition and level of Anxious-Depressed score in the preceding wave were all included as predictors in each model. In only one instance, that of emotion regulation skills, did the putative mechanism predict changes in Anxious-Depressed behaviors, B = −0.13, SE = 0.06, p = .04, 95% CI [−0.25, −0.01].

Given the significant path a and path b involving emotion regulation skills, the joint significance test suggests a significant indirect effect in the prediction of Anxious-Depressed scores. As with the prediction of aggressive behavior, the effect was partially mediating, since treatment condition remained a significant predictor.1

Discussion

The present study tested four sets of putative mechanisms of treatment selected to represent key theoretical mechanisms of effect targeted by the SNAP treatment program: problem solving skills training, emotion regulation skills training, social skills training and changes in parenting behaviors and parental stress. Previous research has demonstrated that SNAP influences positive change on measures of behavioral problems as well as affective problems (Burke & Loeber, in press). The present analyses were designed to test specific putative mechanisms of the SNAP treatment effect on aggressive behavior and anxious-depressed scores. A transitional modeling strategy, in which prior levels of each outcome were included as predictors, led to a robust test of the effects described in the results. Formal tests of mediation were used to assess apparent mechanisms of treatment.

The results support the theoretical model described for the intervention on several domains. Mediating roles were found for social skills and emotion regulation skills, where both were enhanced in the SNAP treatment condition, and both predicted improvements on a measure of aggressive behavior. Emotion regulation skills were also found to predict improvements in anxious-depressed scores. Parenting stress associated with difficult child behavior was also reduced in the SNAP treatment condition, and was also predictive of improvements in boys’ aggression. A marginal effect for changes in positive parenting skills in the SNAP treatment condition, along with prediction from positive parenting to reduced aggressive behavior, was not supported as a mediated relationship in statistical testing. No effects for the selected problem solving skills measures of expectations of punishment, remorse or victim suffering on either outcome were found.

It is important to keep in mind that the structure of the present analyses was specific to tests of mechanisms associated with the specific treatment model of interest in this study, the SNAP program. Because potential mechanisms were initially assessed to identify those that differed by treatment group, this strategy would not identify general mechanisms of treatment that did not differ between SNAP and STND. For example, improvement was evident on parenting practices for children in both SNAP and STND, and testing not reported here showed that parenting practices were strong predictors of changes in aggressive behavior and anxious-depressed behavior. However, because the differences between treatment groups were not significant in these data, indicators of parenting behaviors were largely not examined further in the reported results. These results are similar to Hinshaw (2002), who found evidence that parenting behaviors were predictive of behavioral outcomes, but did not find differences between comparison treatment conditions on parenting behaviors. It would be a mistake to interpret these results to suggest that in general, treatments should not attempt to change parenting behaviors.

In addition, it is also useful to observe that the SNAP treatment group showed significantly greater scores on each of the measures of problem solving, even though these scores did not themselves predict changes in either aggression or anxious-depressed scores. The SNAP treatment program focuses extensively on problem solving, including direct instruction, modeling and role-playing to enhance children’s ability to anticipate potential outcomes of various solutions to problems. Children are taught to anticipate which solutions might make a given problem smaller or bigger. As a result, their increased expectations for a higher likelihood of punishment, remorse or victim suffering, relative to children in the treatment as usual group are not surprising. Nevertheless, the present results do not support a connection between greater expectations for such outcomes due to undesirable behavior and the outcomes studied here.

The results suggest the possibility that different processes may be underpinning change in behavioral and affective outcomes. First, neither aggressive behavior nor anxious-depressed scores predicted subsequent changes in the other outcome. Thus, it is not the case that children were feeling less anxious or depressed as a function of improvements in their aggression, or vice versa. Furthermore, the results identified prosocial behavior, emotion regulation skills and parental distress as mechanisms of change in aggressive behavior, whereas only emotion regulation skills were mediators of anxious-depressed scores. This suggests some discrimination in the nature of the mechanisms associated with either outcome, excepting that improved emotional regulation skills were common partial mediators for each outcome.

Why would prosocial behavior and parental stress predict aggression scores and not anxious-depressed scores? From the perspective of the SNAP treatment model in particular, the SNAP group sessions reinforce prosocial behavior both within the treatment groups and through the content on specific topics. Individualized treatment components continue to address individual needs as well. This focus persistently encourages, models and reinforces using prosocial and non-violent behaviors. Some individuals might ultimately have positive feelings when reflecting upon the successful use of prosocial skills, but for children in this sample, levels of aggressive behaviors themselves did not predict changes in anxious-depressed scores, nor did levels of prosocial behavior.

Parental stress due to difficult child behavior seems more directly related to aggression and thus perhaps not surprising as a mediator. However, general parental stress and parental stress associated specifically with difficult parent-child interactions were not mediators. The aspects of parental stress associated with having a difficult child would seem to be an effect of problem behaviors like aggression, not a predictor of such. It may be that the measure of this aspect of parental stress picked up on some aspect of the parent-child relationship that was not captured by the other dimensions of parenting or parental stress included in these analyses. Alternatively, it may have picked up on changing child behaviors that were independent of concurrent aggression but were nevertheless predictive of future aggression.

An implication of this result might be that, while there may be some generalization across different dimensions of outcomes for a given treatment, exposure to specific elements of a treatment may act upon different treatment mechanisms. These results will need to be replicated, and in particular, nuanced studies will be needed to confirm such specificity between treatment components and mechanisms. Treatment providers may nevertheless be encouraged to think carefully about the interventions they are employing, the processes they are aiming to alter, and the specific goals they are aiming to achieve.

These results should be interpreted with several limitations in mind. The measures of putative mechanisms of treatment used in this study each only represented one aspect of a given mechanism. For instance, problem solving skills do include thinking more fully about the potential outcomes for one’s behavior, and as noted in the case of SNAP treatment, particularly focus on estimating when possible solutions might worsen a problem. Thus, anticipating a higher likelihood of punishment makes sense as one aspect of problem solving. However, problem solving also involves many other elements, such as the ability to recognize the problem, to generate multiple solutions, to generate a variety of different types of solutions, and so on. Representing possible mechanisms of treatment using a measure of only one aspect of the mechanism may not fully reveal which mechanisms are truly associated with outcomes.

A related issue is the concern that the investigation of mechanisms of treatment might have an exploratory and post hoc quality. On the one hand, given the paucity of evidence for treatment mechanisms, there may be some utility in exploratory endeavors. On the other hand, where research involves the post hoc inclusion of many variables to identify potential mediators, spurious associations might lead investigators and treatment providers to erroneous conclusions about how treatments work. In the present study, this concern is mitigated somewhat by the fact that these specific mechanisms were identified for testing in an a priori fashion.

An additional related limitation of this study was that our modeling strategy accounted for putative mediators individually, in separate models. An alternate method, using structural equation modeling, tests multiple mediators simultaneously (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). We opted to examine each of these putative mechanisms of change separately, controlling for lagged effects in an HLM model, but we recognize the possibility that identified mechanisms in one model might have influenced the relationships involving mechanisms in other models as well.

The present study involved only boys. The mechanisms associated with improvements for girls may differ greatly. For instance, girls may benefit differently from changes in interpersonal or communication skills than boys. The present study was specific to a program that has developed gender specific treatment models, and could thus only include boys. However, it will be worthwhile to more fully understand which treatment mechanisms may be more or less relevant for outcomes for boys versus girls.

Table 3.

Selected putative SNAP mechanisms predicting Anxious-Depressed scores.

| Mechanism | B | SE | P | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Solving Skills | |||||

| Punishment | 0.06 | 0.04 | .15 | −0.02 | 0.14 |

| Remorse | 0.04 | 0.03 | .18 | −0.02 | 0.10 |

| Victim Suffering | 0.003 | 0.04 | .92 | −0.07 | 0.08 |

| Prosocial Behaviors | −0.03 | 0.05 | .57 | −0.13 | 0.08 |

| Emotion Regulation Skills | −0.13 | 0.06 | .04 | −0.25 | −0.01 |

| Parenting | |||||

| Positive | −0.02 | 0.02 | .46 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Parental Stress | |||||

| Difficult Child | 0.05 | 0.03 | .11 | −0.01 | 0.11 |

Note: Values of each outcome and the mediator at the preceding wave were included as predictors in each model, as were values for wave and age. The beta coefficient for each row is the value of each unit increase in aggressive behavior for each unit increase in the specified putative mechanism. These represent tests of path b in Figure 1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (07-365-01) from the Department of Health of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to Drs. Loeber and Burke, and by a grant to Dr. Burke (MH 074148) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

1 Our a prior selection of outcomes was driven by an intention to test mechanisms potentially related to specific outcomes. However, it may have been of interest to consider broader constructs as outcomes. We therefore ran models testing the CBCL Externalizing and Internalizing scales as outcomes. The Externalizing scale includes Aggression and Rule Breaking behavior. The pattern of results – that is, which mechanisms were significantly predictive and which were not - was the same for Externalizing as was observed for Aggression as an outcome. Prediction to the Internalizing scale (which includes Somatic Complaints, Withdrawn-Depressed and Anxious-Depressed subscales) did vary from the results described above for the Anxious-Depressed outcome. Specifically, emotion regulation skills did not predict changes in Internalizing scores. Details on these analyses are available upon request from the first author.

Drs. Burke and Loeber have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey D. Burke, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh

Rolf Loeber, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh.

References

- Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index, Third Edition: Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; Odessa, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA School-age Forms & Profiles: University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Handling missing data by maximum likelihood. 2012 Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved from http://www.statisticalhorizons.com/wp-content/uploads/MissingDataByML.pdf.

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augimeri LK, Farrington DP, Koegl CJ, Day DM. The SNAP™ Under 12 Outreach Project: Effects of a community based program for children with conduct problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:799–807. [Google Scholar]

- Augimeri LK, Jiang D, Kogel CJ, Carey J. The Under 12 Outreach Project: Effect of a community-based program for children with conduct problems. Center for Child Committing Offences, Child Development Institute; Toronto, Ontario: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Sterba SK, Hallfors DD. Evaluating group-based interventions when control participants are ungrouped. Multivariate Behavior Research. 2008;43:210–236. doi: 10.1080/00273170802034810. doi: 10.1080/00273170802034810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Boylan K, Rowe R, Duku E, Stepp SD, Hipwell AE, Waldman ID. Identifying the irritability dimension of ODD: Application of a modified bifactor model across five large community samples of children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:841–851. doi: 10.1037/a0037898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Loeber R. The effectiveness of the Stop Now and Plan (SNAP) Program for boys at risk for violence and delinquency. Prevention Science. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0490-2. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Loeber R, Birmaher B. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part II. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1275–1293. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:566–579. doi: 10.1037/a0014565. doi: Doi 10.1037/A0014565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Ebesutani C, Young J, Becker KD, Nakamura BJ, Starace N. Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2011;18:154–172. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group . Psychometric properties of the Social Competence Scale - teacher and parent ratings. Pennsylvania State University; University Park, PA: 1995. (Fast Track Project Technical Report) [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Kavanagh KA. An experimental test of the coercion model: Linking theory, measurement, and intervention. In: McCord J, Tremblay RE, editors. Preventing antisocial behavior: Interventions from birth through adolescence. Guilford; New York, NY: 1992. pp. 253–282. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Tsukayama E, May H. Establishing causality using longitudinal hierarchical linear modeling: An illustration predicting achievement from self-control. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2010;1:311–317. doi: 10.1177/1948550609359707. doi: 10.1177/1948550609359707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. doi: 792194652 [pii] 10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child Symptom Inventories manual. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Letourneau EJ, Chapman JE, Borduin CM, Schewe PA, McCart MR. Mediators of change for multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:451. doi: 10.1037/a0013971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. Intervention research, theoretical mechanisms, and causal processes related to externalizing behavior patterns. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:789–818. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Evidence-based treatment research: Advances, limitations, and next steps. American Psychologist. 2011;66:685–698. doi: 10.1037/a0024975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegl CJ, Farrington DP, Augimeri LK, Day DM. Evaluation of a targeted cognitive behavioural program for children with conduct problems - the SNAP™ Under 12 Outreach Project: Service intensity, age and gender effects on short and long term outcomes. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;13:441–456. doi: 10.1177/1359104508090606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36:249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. doi: 10.1207/S15327906mbr3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Lochman JE. Moving beyond efficacy and effectiveness in child and adolescent intervention research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:373. doi: 10.1037/a0015954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landenberger N, Lipsey M. The positive effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for offenders: A meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2005;1:451–476. doi: 10.1007/s11292-005-3541-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Contextual social-cognitive mediators and child outcome: A test of the theoretical model in the Coping Power program. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:945–967. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Lochman JE, Frick PJ. Callous/unemotional traits and social-cognitive processes in adjudicated youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:364–371. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00018. doi: Doi 10.1097/01.Chi.0000037027.04952.Df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. Predicting future clinical adjustment from treatment outcome and process variables. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:275. [Google Scholar]

- Perry DG, Perry LC, Rasmussen P. Cognitive social learning mediators of aggression. Child Development. 1986;57:700–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH. Social skills training with children and young people: Theory, evidence and practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2003;8:84–96. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, Hammond M. Preventing conduct problems, promoting social competence: A parent and teacher training partnership in Head Start. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:283–302. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]