Abstract

Objectives To assess the stability and outcomes of patients with cholesterol granulomas at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Design A retrospective review of neuroradiology magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies was performed. The number of newly diagnosed cases of cholesterol granuloma per year was determined. Additional data included age and gender, clinical presentation if applicable, growth on imaging follow-up, and recurrence on postoperative follow-up if applicable.

Participants Inclusion criteria included patients who underwent MRI studies between January 1, 2009 and July 1, 2013. Upon review of imaging of these patients, 18 patients had findings compatible with cholesterol granuloma.

Results During the study period, an average of three cases of cholesterol granuloma were diagnosed on MRI per year. Three of 18 patients underwent treatment. Two underwent surgery, both of whom demonstrated recurrence on postoperative follow-up imaging. One patient who underwent computed tomography–guided percutaneous aspiration and Gelfoam (Pfizer, New York, United States) embolization had no recurrence on imaging follow-up of up to 23 months. Among the patients who were observed without intervention, growth was identified in only one patient.

Conclusions Cholesterol granulomas are a rare entity; however, their appearance on imaging may be greater than previously reported. Most of the lesions demonstrate stability and can be observed.

Keywords: cholesterol granuloma, review, stability, aspiration, embolization

Introduction

Cholesterol granulomas of the petrous apex are rare lesions of uncertain etiology. Traditionally, it was hypothesized that bleeding within petrous apex air cells is related to a vacuum phenomenon due to the blockage of pneumatic pathways by mucosal swelling.1 More recently, it was proposed that they may occur from a repeating cycle of hemorrhage from exposed marrow into a petrous apex air cell with resulting cystic expansion.1 Although it is a commonly described lesion of the petrous apex in radiology literature, the reported incidence is quite low, ∼ 0.6 per 1 million people in the general population.2 In practice, we have experienced a significantly higher incidence in the general patient population at Brigham and Women's Hospital. The vast majority of these lesions remain stable over time, but a subset demonstrates symptomatic growth that requires treatment that traditionally entails complex skull base surgery to establish drainage and aeration.3

Our recent report highlights a novel case of a patient with a symptomatic cholesterol granuloma treated with percutaneous aspiration and Gelfoam (Pfizer, New York, United States) embolization under computed tomography (CT) guidance. In this particular case, the patient currently remains recurrence free at just under 2 years.4 This experience, as well as the possibility that these lesions are more common than previously reported, prompted a further investigation of the natural course of cholesterol granulomas in the general population. The objective was to assess the stability, treatment, and outcomes of patients with cholesterol granulomas at an academic teaching hospital.

Materials and Methods

An initial query was performed using the Research Patient Data Registry, a centralized clinical data registry compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act affiliated with Partners Healthcare and Brigham and Women's Hospital. The query entailed requesting radiologic reports and patient demographic data on every magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head, neck, brain, spine, and orbits performed at Brigham and Women's Hospital between January 1, 2009, and July 1, 2013. Given the high volume of MRI studies, this time period was segmented into four separate queries. Data were returned in the form of multiple searchable and sortable database files that included the following data: radiology reports, type of radiologic study, patient name, and patient medical record number. All data were stored on a laptop encrypted and provided by Partners Healthcare.

The radiology reports were subsequently searched using the keywords cholesterol granuloma and cholesterol cyst. The term cholesterol cyst was used as a keyword because it has been noted to be used synonymously with the term cholesterol granuloma in the literature. This search returned a total of 25 patients. MRI and any additional CT studies of these patients were retrospectively reviewed by two board-certified or board-eligible neuroradiologists to confirm an imaging diagnosis of cholesterol granuloma. Imaging characteristics included characteristic high T1 signal, expansile morphology without erosive or invasive features, and classic petrous apex location.5 Available follow-up studies were also reviewed to document the long-term stability or slow growth typically associated with this entity. Additionally, relevant clinical data, including progress notes and any available relevant operative notes, were reviewed using the electronic medical record at Brigham and Women's Hospital. Patients who, in retrospect, did not have lesions compatible with an imaging diagnosis of cholesterol granuloma were excluded from the study. After excluding these patients, our patient population included 18 patients: 7 males and 11 females. Recorded data included patient demographics, size, date of initial diagnosis on MRI, imaging follow-up and growth, clinical symptomatology, surgical intervention if performed, and posttreatment follow-up imaging.

Results

In 2009, there were 3 newly diagnosed patients (Figs. 1 2 3) with cholesterol granuloma on MR imaging of 9,129 medical record numbers, which represented patients who had MRI studies of the head, neck, brain, and spine that year. Similarly, in 2010, there were 7 newly diagnosed patients of 9,229 patients. In 2011, there was 1 newly diagnosed patient of 9,643 patients. Finally, during the period from January 1, 2012, to July 1, 2013, 3 patients were diagnosed of 13,720 patients. Overall, 22% of patients (4 of 18) had a diagnosis of cholesterol granuloma on imaging before 2009. There was an average of 3 newly diagnosed patients each year of an average of 9,271 patients per year who underwent neuroradiology MRI studies.

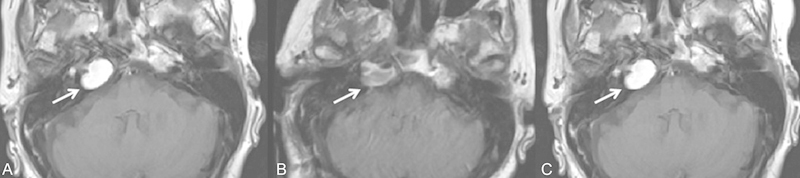

Fig. 1.

A 73-year-old woman who presented with diplopia and was clinically discovered to have a right abducens nerve palsy (see arrow). (A) T1-weighted axial noncontrast imaging demonstrates an expansile lesion in the right petrous apex with high T1 signal, compatible with a cholesterol granuloma. The patient elected to undergo surgical intervention. (B) First postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 3 days status postresection via a retrosigmoid approach demonstrates T1 hyperintense and intermediate intense signal within the right petrous apex (see arrow) that is not as expansile as the preoperative study. These findings likely reflect a combination of postoperative blood products and/or residual cholesterol granuloma. (C) Follow-up MRI at 2 months status postsurgery demonstrates a reaccumulation of T1 hyperintense material within the right petrous apex lesion (see arrow) that has again become expansile and is compatible with interval growth of cholesterol granuloma. Clinically, the patient's diplopia improved with mild residual symptoms. However, she only had neurosurgical follow-up for 16 months status postsurgery.

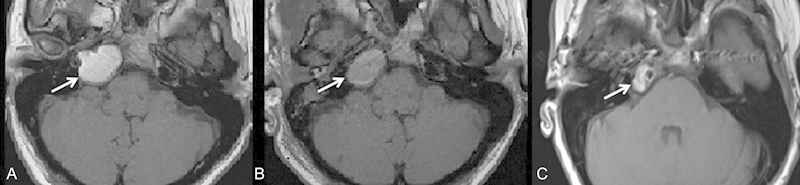

Fig. 2.

A 38-year-old woman who presented with sudden onset diplopia, secondary to a right abducens nerve palsy on examination (see arrow), as well as dizziness. (A) Noncontrast T1-weighted axial imaging demonstrates an expansile T1-hyperintense lesion in the right petrous apex compatible with a cholesterol granuloma. The patient underwent surgical resection via a middle cranial fossa approach with imaging guidance. (B) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 2 days status postsurgery demonstrates unchanged size of the lesion; however, there is a reduction in the T1 hyperintense signal (see arrow). (C) MRI follow-up ∼ 5 months status postsurgery demonstrates complete reduction of high T1 signal within the inferior component of the lesion but persistent high T1 signal within the superior component (see arrow) suggestive of persistent cholesterol granuloma. On her most recent clinical follow-up 9 months status postsurgery, the patient's diplopia had resolved, but she still complains of vestibular symptoms as well as headache.

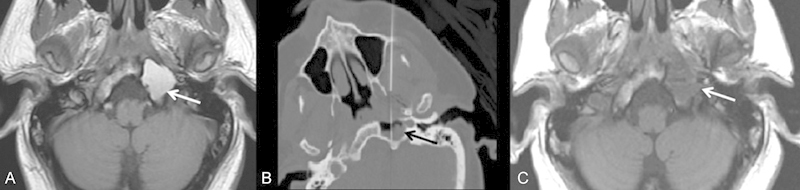

Fig. 3.

A 35-year-old man with prior medical history of treated mediastinal germ cell tumor who presented with several weeks of gradually increasing pain along the left side of the head and trapezius as well as difficulty with speech and swallowing. (A) Axial T1-weighted image from the preprocedural magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates an expansile T1 hyperintense lesion in the left petrous apex (see arrow) that was noted to be enlarging from prior studies. The patient was referred for biopsy to exclude metastatic disease given a prior history of malignancy. (B) Axial intraprocedural computed tomography demonstrates a 22-gauge needle with its tip within the lesion (see arrow). Aspiration yielded dark motor oil–like fluid that later turned a lighter, more serosanguineous color. Subsequently, Gelfoam slurry was injected into the aspirated cavity and the needle was removed. (C) Axial T1-weighted image from a follow-up MRI 23 months status postaspiration and Gelfoam embolization demonstrates complete resolution of T1 hyperintense signal within the lesion (see arrow). The patient had complete resolution of symptoms on clinical follow-up. (Reprinted with permission from Lee TC, Raghavan D, Curtin HD. Image-guided percutaneous aspiration and Gelfoam treatment of petrous apex cholesterol granuloma: a new theory and method for diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 2013;74:342–346.)

The average size of cholesterol granulomas in our patient population was 1.8 cm (range: 0.5–3.1 cm). A total of 44% of patients (8 of 18) were symptomatic, and symptoms included tinnitus, headache, hearing loss, dizziness, and diplopia. In the remaining patients, it is not known whether these patients had symptoms or not because the lesions were incidentally discovered, and no stated symptomatology was in the electronic medical record. Overall, 11% of patients (2 of 18) demonstrated lesion growth on follow-up imaging.

A total of 83% of patients (15 of 18) were observed without any treatment. Table 1 summarizes these patients. Of these patients, only one patient demonstrated growth on follow-up imaging. However, in 20% of patients who were observed (3 of 15), follow-up imaging was not performed and lesion growth could not be assessed. One of these patients who had developed symptoms without evidence of lesion growth underwent antibiotic therapy due to coexisting otitis media and Eustachian tube dysfunction.

Table 1. Nonsurgical patients: demographic data and follow-up imaging.

| Patient number | Gender | Age, y | Sex | Size, cm | Side | Follow-up, mo | Growth? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 53 | Tinnitus | 1.7 | R | 140 | No |

| 2 | M | 52 | headache, tinnitus, hearing loss | 3.1 | R | 29 | No |

| 3 | M | 26 | Not known | 1.9 | R | 0 | NA |

| 4 | F | 23 | Not known | 1.5 | R | 16.75 | No |

| 5 | F | 53 | Not known | 1.6 | L | 57.5 | No |

| 6 | F | 84 | Not known | 0.5 | L | 13 | No |

| 7 | M | 46 | Tinnitus | 2.2 | L | 49 | No |

| 8 | F | 51 | Dizziness, hearing loss | 1.9 | R | 61 | Yes |

| 9 | F | 43 | Not known | 0.7 | R | 116 | No |

| 10 | M | 70 | Not known | 2.2 | L | 47 | No |

| 11 | F | 26 | Not known | 1.1 | L | 30 | No |

| 12 | M | 50 | Not known | 2 | R | 122 | No |

| 13 | F | 44 | Headache, dizziness, tinnitus | 0.9 | R | 1 | No |

| 14 | F | 20 | Not known | 1.8 | R | 0 | NA |

| 15 | M | 35 | Not known | 1.6 | L | 0 | NA |

Abbreviations: F, female; L, left; M, male; NA, not applicable; R, right.

Overall, 16% of patients (3 of 18) underwent treatment; two patients underwent open surgery (Figs. 1 and 2) and one patient underwent CT-guided aspiration with Gelfoam embolization (Fig. 3). These results are summarized in Table 2. Both of the patients who underwent neurosurgical intervention had developed symptoms, but growth was unable to be assessed because there was no significant preoperative imaging follow-up. Of the two patients who underwent surgery, both patients demonstrated recurrent disease on follow-up imaging ranging from 14.5 to 3 months. Both of these patients had improvement of their symptoms without complete resolution on clinical follow-up. However, in one patient there was no permanent fenestration created for aeration of the cholesterol granuloma cavity. Regarding the other patient, the operative note did not specify whether or not a fenestration was created. One of these patients did not have clinical neurosurgical follow-up after 14 months. One patient who had developed symptoms as well as demonstrating lesion growth on imaging underwent CT-guided aspiration with Gelfoam embolization as an outpatient. This patient has remained symptom and recurrence free at 23 months on both clinical and imaging follow-up.

Table 2. Patients who underwent intervention for cholesterol granuloma: demographic data and follow-up imaging.

| Gender | Age, y | Symptoms | Size, cm | Side | Follow-up | Growth? | Treatment | Clinical postoperative follow-up | Postoperative follow-up, mo | Recurrence/Residual | Immediate postsurgical complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 73 | Diplopia from right CN 6 palsy | 2.2 | R | 0.5 | NA; too little follow-up | Retrosigmoid approach with imaging guidance | Improvement in diplopia | 14.5 | Yes | No |

| F | 38 | Diplopia, dizziness | 2.6 | R | 0.25 | NA; too little follow-up | Middle cranial fossa approach with imaging guidance | Resolution of diplopia, dizziness persists | 9 | Yes | No |

| M | 35 | Headache, CN 12 palsy, aphasia | 2.9 | L | 59 | Yes | CT-guided aspiration and Gelfoam treatment | Resolution of symptoms | 23 | No | No |

Abbreviations: CN, cranial nerve; CT, computed tomography; F, female; L, left; M, male; NA, not applicable; R, right.

Discussion

Although it is difficult to calculate true incidence based on the current imaging data, an average of three newly diagnosed cases per year suggests an incidence higher than previously stated. Additionally, the consensus of the current literature is that most of these lesions are either stable or demonstrate slow growth, and only a small subset of patients experience significant growth and/or symptoms.6 7 However, all of the studies reviewed in the literature were retrospective analyses that primarily included patients who had already been referred for neurosurgical consultation. Because the patient population from our study was acquired by searching our patient imaging database and not relying on neurosurgical referrals, data from this study may provide a more accurate representation of the overall incidence and stability of these lesions in the general population.

Patients who are symptomatic typically present with sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, dizziness, or vertigo as the most common clinical presentation.3 Additional signs and symptoms reported in the literature have included temporal headaches and facial pain, and cranial neuropathies that suggest dural involvement and cranial nerve compression, respectively.3 Patients in our study developed symptoms similar to those reported in the literature.

Surgery is the traditional mode of therapy for patients who are symptomatic or demonstrate aggressive lesion growth. There is controversy regarding the best surgical approach with various surgical approaches described including infralabyrinthine, middle cranial fossa, retrosigmoid, transotic, and translabyrinthine approaches.7 8 In a 2002 study by Brackmann and Toh, minor complications were reported in 8.8% of their patient population (3 of 34 patients) that included tympanic membrane perforation and superficial wound drainage.9 Recurrence rate in this study was reported to be 14.7% (5 of 34 patients) based on both clinical and imaging findings.9 Over the past 15 years, an endonasal endoscopic approach has gained popularity.7 10 11 12 This approach is primarily useful when the lesion abuts the sphenoid sinus and there is no significant intracranial extension. A 2012 patient series by Paluzzi et al reported a complication rate of 18% (3 of 17 patients) via the endoscopic endonasal approach that included epistaxis, chronic serous otitis, eye dryness, and transient abducens nerve palsy.10 This same series reported a recurrence rate of 12% (2 of 17 patients).10 Additionally, a review article by Gore et al reported a recurrence rate of 5% based on a literature review.7 Although an endonasal approach may be a relatively minimally invasive treatment option, its complication and recurrence rates remain comparable with those of traditional surgical techniques.

Of the two patients in our study who underwent neurosurgical intervention via retrosigmoid and middle cranial fossa approaches, both patients had a recurrence of imaging and incomplete resolution of symptoms. In particular, both of these surgeries involved intraoperative imaging guidance. The use of imaging guidance for surgical intervention has also been described in the literature, primarily in the form of case reports.13 14 15 The patient who underwent CT-guided percutaneous aspiration and Gelfoam embolization had complete resolution of his symptoms and currently remains disease free on imaging on 23-month follow-up. This patient continues to be followed. Given the morbidity of surgical intervention, a need exists for a more minimally invasive approach to treating patients with cholesterol granuloma. Further investigation of this technique's efficacy and safety in a larger patient population is warranted given the potential to reduce surgical morbidity and avoid inpatient hospitalization.

A primary limitation of this study is the relative paucity of surgical cases, related to the fact that patient population was acquired by querying a hospital patient registry and not through neurosurgical referrals. Although this hinders characterization of postoperative complications and calculation of accurate recurrence rates, the primary aim of the study was to better assess the appearance of the diagnosis of cholesterol granuloma in the imaging database of a large academic hospital. Characterization of cholesterol granuloma recurrence and postoperative complications has already been extensively discussed in the surgical literature. Another limitation is that our initial query requested data on every MRI study between the specified dates; however, it did not include CT studies of the head and neck. It is possible that, given the nonaggressive behavior of most cholesterol granulomas, incidentally discovered lesions in asymptomatic patients may not be imaged with MRI. Therefore, these patients would not have been included in the patient population and the data would be an underrepresentation of the true incidence of cholesterol granulomas. However, given the lack of histopathology of patients who did not undergo intervention, MRI is needed for characteristic imaging diagnosis for the purposes of inclusion into this study.

Conclusion

This study suggests that the incidence of cholesterol granuloma in the general population is higher than previously reported. Most of these lesions remain stable or demonstrate slow growth over time. Of those that are symptomatic or demonstrate aggressive growth, open surgical drainage is the traditional mode of therapy. However, given the high recurrence rate reported in the literature and in the current study, more minimally invasive techniques such as percutaneous aspiration and Gelfoam embolization is an attractive option and warrants further investigation.

References

- 1.Jackler R K Cho M A new theory to explain the genesis of petrous apex cholesterol granuloma Otol Neurotol 200324196–106.; discussion 106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo W WM, Solti-Bohman L G, Brackmann D E, Gruskin P. Cholesterol granuloma of the petrous apex: CT diagnosis. Radiology. 1984;153(3):705–711. doi: 10.1148/radiology.153.3.6494466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosnier I, Cyna-Gorse F, Grayeli A B. et al. Management of cholesterol granulomas of the petrous apex based on clinical and radiologic evaluation. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23(4):522–528. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200207000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee T C, Raghavan D, Curtin H D. Image-guided percutaneous aspiration and Gelfoam treatment of petrous apex cholesterol granuloma: a new theory and method for diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2013;74(6):342–346. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1345107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoa M, House J W, Linthicum F H Jr, Go J L. Petrous apex cholesterol granuloma: pictorial review of radiological considerations in diagnosis and surgical histopathology. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(4):339–348. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thedinger B A, Nadol J B Jr, Montgomery W W, Thedinger B S, Greenberg J J. Radiographic diagnosis, surgical treatment, and long-term follow-up of cholesterol granulomas of the petrous apex. Laryngoscope. 1989;99(9):896–907. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198909000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gore M R, Zanation A M, Ebert C S, Senior B A. Cholesterol granuloma of the petrous apex. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44(5):1043–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanna M, Dispenza F, Mathur N, De Stefano A, De Donato G. Otoneurological management of petrous apex cholesterol granuloma. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009;30(6):407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brackmann D E, Toh E H. Surgical management of petrous apex cholesterol granulomas. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23(4):529–533. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paluzzi A, Gardner P, Fernandez-Miranda J C. et al. Endoscopic endonasal approach to cholesterol granulomas of the petrous apex: a series of 17 patients: clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(4):792–798. doi: 10.3171/2011.11.JNS111077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanation A M, Snyderman C H, Carrau R L, Gardner P A, Prevedello D M, Kassam A B. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for petrous apex lesions. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(1):19–25. doi: 10.1002/lary.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhanasekar G, Jones N S. Endoscopic trans-sphenoidal removal of cholesterol granuloma of the petrous apex: case report and literature review. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125(2):169–172. doi: 10.1017/S0022215110002227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michaelson P G, Cable B B, Mair E A. Image-guided transphenoidal drainage of a cholesterol granuloma of the petrous apex in a child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;57(2):165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiNardo L J, Pippin G W, Sismanis A. Image-guided endoscopic transsphenoidal drainage of select petrous apex cholesterol granulomas. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24(6):939–941. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200311000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pietrantonio A, D'Andrea G, Famà I, Volpini L, Raco A, Barbara M. Usefulness of image guidance in the surgical treatment of petrous apex cholesterol granuloma. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:257263. doi: 10.1155/2013/257263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]