Abstract

Study Design Case report.

Objective To present two cases of neurogenic shock that occurred immediately following posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) and that appeared to have been caused by the vasovagal reflex after dural injury and incarceration of the cauda equina.

Case Report We present two cases of neurogenic shock that occurred immediately following PLIF. One patient had bradycardia, and the other developed cardiac arrest just after closing the surgical incision and opening the drainage tube. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed immediately, and the patients recovered successfully, but they showed severe motor loss after awakening. The results of laboratory data, chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, computed tomography, and echocardiography ruled out pulmonary embolism, hemorrhagic shock, and cardiogenic shock. Although the reasons for the postoperative shock were obscure, reoperation was performed to explore the cause of paralysis. At reoperation, a cerebrospinal fluid collection and the incarceration of multiple cauda equina rootlets through a small dural tear were observed. The incarcerated cauda equina rootlets were reduced, and the dural defect was closed. In both cases, the reoperation was uneventful. From the intraoperative findings at reoperation, it was thought that the pathology was neurogenic shock via the vasovagal reflex.

Conclusion Incarceration of multiple cauda equina rootlets following the accidental dural tear by suction drainage caused a sudden decrease of cerebrospinal fluid pressure and traction of the cauda equina, which may have led to the vasovagal reflex.

Keywords: bradycardia, cardiac arrest, incarceration of the cauda equine, neurogenic shock, vasovagal reflex, spinal surgery, posterior lumbar interbody fusion

Introduction

Neurogenic shock occurs often after acute spinal cord injury, but postoperative neurogenic shock is a serious and very rare sequela in the field of spinal surgery. The purpose of this article is to present two cases of neurogenic shock that occurred immediately following posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) and that appeared to have been caused by the vasovagal reflex following dural injury and incarceration of the cauda equina. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to describe neurogenic shock due to the vasovagal reflex just after lumbar spinal surgery.

Case Reports

Case One

A 76-year-old woman complained of low back pain, bilateral leg pain, and intermittent claudication. She had no history of previous health problems, including no cardiovascular events. No motor loss was observed preoperatively. Preoperative radiographic studies demonstrated L5 degenerative spondylolisthesis (Fig. 1A).

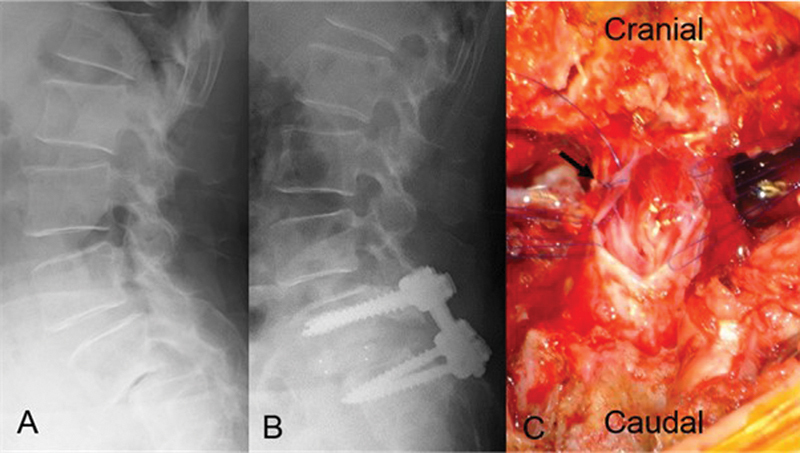

Fig. 1.

Plain lateral radiographs (A, B) and intraoperative photograph (C). (A) Preoperative plain radiograph shows L5 degenerative spondylolisthesis with 47% vertebral slip. (B) Postoperative plain radiograph shows L5 vertebral slippage of 23%. (C) Intraoperative imaging after enlargement of the dural tear. The location of the new dural tear is different from that of the primary dural tear (arrow).

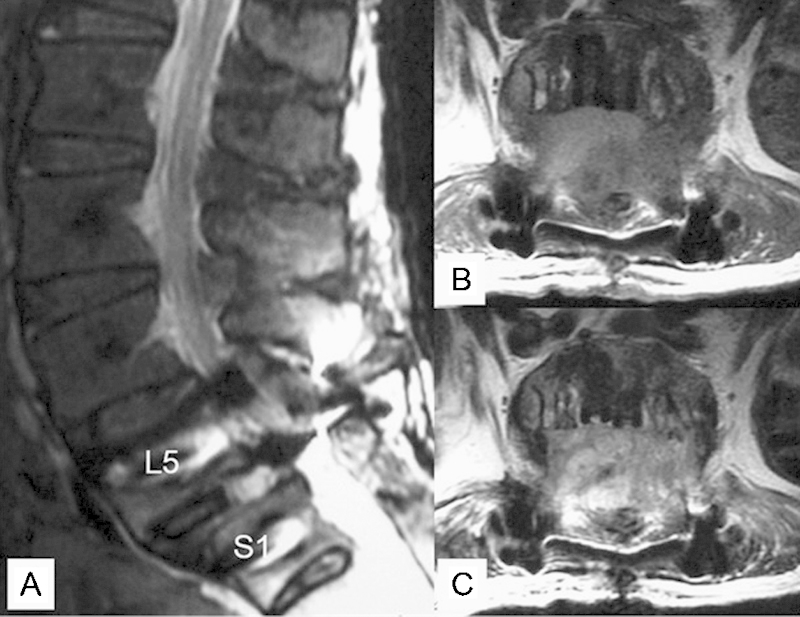

PLIF at the L5–S1 level was performed in the prone position. A dural tear occurred intraoperatively and was repaired. A dural sealing seat (to cover the repaired dura matter) was not used because no cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage was detected after dural tear repair even when intrathoracic pressure was increased. While general anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane and remifentanil, her hemodynamics remained stable. A 5-mm-diameter drainage tube was placed on the dorsal side of the lamina. Just after closing the surgical incision and opening the drainage tube, severe bradycardia and hypotension occurred suddenly. An arterial pressure wave was suddenly absent, and the heart rate dropped from 78 to 44 beats per minute. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with injection of positive inotropic cardiac agents was performed immediately after the patient's position was changed from prone to supine, and the patient recovered successfully. Ephedrine was administered, followed by continuous infusion of dopamine. The results of laboratory data, chest X-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG), computed tomography (CT), and echocardiography ruled out pulmonary embolism, hemorrhagic shock, and cardiogenic shock. However, severe motor loss with a manual muscle test (MMT) grade of 1 in the gastrocnemius and peroneus longus muscles was detected after awakening. Postoperative lateral radiographs showed 23% slip (Fig. 1B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a T1 low-iso, T2 iso-high intensity mass around the dural sac at the L5–S1 level (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Primary postoperative magnetic resonance (MR) images. (A) Sagittal T2-weighted image. (B, C) Axial MR images at the L5/S1 level (B, T1-weighted image; C, T2-weighted image). MR images show the low-iso intensity mass on the T1-weighted image, and the iso-high intensity mass on the T2-weighted image around the dural sac at the L5–S1 level.

Because the reasons for the postoperative shock were unclear, reoperation was performed to explore the cause of paralysis on the day following primary operation. At reoperation, a cerebrospinal fluid collection and the incarceration of multiple cauda equina rootlets through a newly developed dural tear were observed. The location of the new dural tear was different from the primary site of the dural tear that was repaired at the first operation. The incarcerated cauda equina rootlets were pale in color and extremely swollen due to venous congestion. After enlargement of the dural tear, the incarcerated cauda equina rootlets were released and reduced (Fig. 1C), and the dural defect was then closed and covered posteriorly with fibrin glue. The reoperation was uneventful. The motor loss improved gradually after reoperation, but motor loss with an MMT grade of 3 in the gastrocnemius and 1 in the peroneus longus muscle remained 4 years after reoperation. However, the patient could walk with a cane and an ankle foot orthosis.

Case Two

An 83-year-old woman complained of low back pain, bilateral leg pain, and intermittent claudication. She had a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, prinzmetal angina, and asthma. No motor loss was detected preoperatively. Preoperative radiographic studies demonstrated L4 degenerative spondylolisthesis.

PLIF at the L4–5 level was performed. No dural tear or CSF leakage occurred intraoperatively. While general anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane and remifentanil, her hemodynamics remained stable. A 5-mm-diameter drainage tube was placed on the dorsal side of the lamina. Similar to case one, severe bradycardia occurred suddenly, and cardiac arrest developed immediately after closing the surgical incision and opening the drainage tube. CPR was immediately performed, and the patient recovered successfully. Because pulmonary embolism or a cardiac lesion was initially suspected, percutaneous cardiopulmonary support with heparinization was used. ECG, chest CT, and cardiac catheterization showed no abnormal findings, although brain CT revealed pneumocephalus. The patient showed severe neurologic deficits after surgery, and postoperative bleeding from the drainage tube of ∼4000 mL developed because of heparinization. On the same day, reoperation was performed to confirm the bleeding sources and explore the cause of paralysis. Intraoperatively, a CSF collection and a cluster of edematous cauda equina rootlets through a small dural defect were observed, although no active bleeding source was found. The bleeding appeared to be oozing due to heparinization. Reduction of the incarcerated cauda equina rootlets and repair of the dural defect were performed. The motor loss recovered fully a few days after reoperation.

Discussion

The present cases shared some common characteristics: both were elderly woman with degenerative spondylolisthesis, had incarceration of the cauda equina, and experienced shock that developed immediately following closure of the surgical incision and opening of the drainage tube.

Neurogenic, hypovolemic, hemorrhagic, and cardiogenic shock were considered as pathology of the intra-/postoperative shock. In the present cases, hemorrhagic or cardiogenic shock appeared unlikely based on the results of various examinations. From the intraoperative findings at reoperation, the pathology was thought to be neurogenic shock via the vasovagal reflex in some form or other. Many reports have described that various mechanisms could cause vasovagal responses.1 Although some reports have described intraoperative shock due to vasovagal reflex in the area of digestive and respiratory surgery, there have been no reports in the field of spinal surgery. In the present cases, incarceration of multiple cauda equina rootlets following the accidental dural tear may have caused a sudden decrease of cerebrospinal fluid pressure and traction of the cauda equina, which might have stimulated the vasovagal reflex. The vasovagal reflex then caused severe bradycardia and cardiac arrest.

An incidental dural tear is a relatively common occurrence during spinal surgery.2 Previously, we reported the complications of PLIF,3 and a dural tear was observed in 7.6% of cases, which was similar to the results of previous reports of dural tear incidence from 5.5 to 10.1%.3 4 5 6 On the other hand, there were few reports of postoperative dural tears. Some reports described a postoperative dural tear following chronic mechanical irritation due to the edge of a broken wire, a residual bone spike, and the suction of a drainage tube.7 8 Furthermore, Nakayama et al first reported postoperative incarceration of the cauda equina following dural injury due to a drainage tube.8 In the present cases, a dural tear and incarceration of the cauda equina may have been caused by suction of a drainage tube, similar to Nakayama et al. Additionally, spondylolisthesis in elderly patients might contribute to fragility of the dura mater.

Dura-related complications are generally considered of little consequence to the final outcome. However, some series have reported that intracranial hypotension due to reduction of CSF volume and pressure caused a cerebral hematoma or cerebral herniation.9 10 In case two, an asymptomatic pneumocephalus was detected on CT, but no cerebral hematoma or cerebral herniation was seen. A rare but potentially devastating complication of iatrogenic CSF leakage is entrapment and incarceration of nerve roots at the site of the dural defect.11 12 13 14 15 16 17 This could cause irreversible nerve damage through strangulation and might lead to a permanent neurologic deficit.11 However, it was very hard to decide whether reoperation was appropriate after shock developed. Postoperative MRI did not demonstrate the apparent pathogenesis responsible for the severe motor loss. With minor motor loss, a wait-and-see attitude would be justifiable, but severe motor loss would tend to bias the decision toward reoperation after the development of shock. Even in the present cases, we hesitated to reoperate because the cause of the shock remained unclear. However, late intervention could produce a serious permanent motor loss.3 After all, case one, who underwent reoperation on the day following the primary operation, had a permanent motor loss, and case two, who underwent reoperation on the same day, recovered fully. These results suggest that if idiopathic severe motor loss occurs postoperatively, reoperation to explore the cause of paralysis should be performed as soon as possible because of the possibility of incarceration of the cauda equina.

Conclusions

Two cases of neurogenic shock following PLIF that appeared to be caused by the vasovagal reflex following dural injury and incarceration of the cauda equina were described. If idiopathic severe motor loss occurs postoperatively, reoperation to explore the cause of paralysis should be performed as soon as possible given the possibility of incarceration of the cauda equina.

Footnotes

Disclosures Tomiya Matsumoto, none Shinya Okuda, none Takamitsu Haku, none Kazuya Maeda, none Takafumi Maeno, none Tomoya Yamashita, none Ryoji Yamasaki, none Shigeyuki Kuratsu, none Motoki Iwasaki, none

References

- 1.Kinsella S M, Tuckey J P. Perioperative bradycardia and asystole: relationship to vasovagal syncope and the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86(6):859–868. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cammisa F P Jr, Girardi F P, Sangani P K, Parvataneni H K, Cadag S, Sandhu H S. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(20):2663–2667. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okuda S, Miyauchi A, Oda T, Haku T, Yamamoto T, Iwasaki M. Surgical complications of posterior lumbar interbody fusion with total facetectomy in 251 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4(4):304–309. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elias W J Simmons N E Kaptain G J Chadduck J B Whitehill R Complications of posterior lumbar interbody fusion when using a titanium threaded cage device J Neurosurg 200093(1, Suppl):45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivet D J, Jeck D, Brennan J, Epstein A, Lauryssen C. Clinical outcomes and complications associated with pedicle screw fixation-augmented lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1(3):261–266. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.1.3.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jutte P C, Castelein R M. Complications of pedicle screws in lumbar and lumbosacral fusions in 105 consecutive primary operations. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(6):594–598. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0469-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosacco S J, Gardner M J, Guille J T. Evaluation and treatment of dural tears in lumbar spine surgery: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(389):238–247. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200108000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakayama Y, Ohta H, Matsumoto Y. et al. Reports of two cases for dural tear due to drainage tube after lumbar spinal surgery. Seikeigeka to Saigaigeka. 2013;62(2):261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas G, Jayaram H, Cudlip S, Powell M. Supratentorial and infratentorial intraparenchymal hemorrhage secondary to intracranial CSF hypotension following spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(18):E410–E412. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200209150-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sciubba D M, Kretzer R M, Wang P P. Acute intracranial subdural hematoma following a lumbar CSF leak caused by spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(24):E730–E732. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000192208.66360.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadani M, Findler G, Knoler N, Tadmor R, Sahar A, Shacked I. Entrapped lumbar nerve root in pseudomeningocele after laminectomy: report of three cases. Neurosurgery. 1986;19(3):405–407. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kothbauer K F, Seiler R W. Transdural cauda equina incarceration after microsurgical lumbar discectomy: case report. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(6):1449–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishi S, Hashimoto N, Takagi Y, Tsukahara T. Herniation and entrapment of a nerve root secondary to an unrepaired small dural laceration at lumbar hemilaminectomies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20(23):2576–2579. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199512000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connor D, Maskery N, Griffiths W E. Pseudomeningocele nerve root entrapment after lumbar discectomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23(13):1501–1502. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199807010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavlou G Bucur S D van Hille P T Entrapped spinal nerve roots in a pseudomeningocoele as a complication of previous spinal surgery Acta Neurochir (Wien) 20061482215–219., discussion 219–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Töppich H G, Feldmann H, Sandvoss G, Meyer F. Intervertebral space nerve root entrapment after lumbar disc surgery. Two cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19(2):249–250. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199401001-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oterdoom D L, Groen R J, Coppes M H. Cauda equina entrapment in a pseudomeningocele after lumbar schwannoma extirpation. Eur Spine J. 2010;19 02:S158–S161. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1219-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]