Abstract

Objective

To describe study design, patients, centers, treatments, and outcomes of a traumatic brain injury (TBI) practice-based evidence (PBE) study and to evaluate the generalizability of the findings to the US TBI inpatient rehabilitation population.

Design

Prospective, longitudinal observational study

Setting

10 inpatient rehabilitation centers (9 US, 1 Canada)

Participants

Patients (n=2130) enrolled between October 2008 and Sept 2011, and admitted for inpatient rehabilitation after an index TBI injury

Interventions

Not applicable

Main Outcome Measures

Return to acute care during rehabilitation, rehabilitation length of stay, Functional Independence Measure (FIM) at discharge, residence at discharge, and 9 months post-discharge rehospitalization, FIM, participation, and subjective wellbeing.

Results

Level of admission FIM Cognitive score was found to create relatively homogeneous subgroups for subsequent analysis of best treatment combinations. There were significant differences in patient and injury characteristics, treatments, rehabilitation course, and outcomes by admission FIM Cognitive subgroups. TBI-PBE study patients overall were similar to US national TBI inpatient rehabilitation populations.

Conclusions

This TBI-PBE study succeeded in capturing naturally occurring variation within patients and treatments, offering opportunities to study best treatments for specific patient deficits. Subsequent papers in this issue report differences between patients and treatments and associations with outcomes in greater detail.

Keywords: brain injuries, comparative effectiveness research, rehabilitation

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) inpatient rehabilitation has been studied largely as an undifferentiated “black box”, with comparisons being made between patients who received rehabilitation and those who did not, between those who received it early versus late, or between those who received intensive treatment and those whose program was less intense.1–6 However, Chestnut et al. observed that knowing time spent without knowing what impairments were being treated or what methods of treatment were used may be too blunt an instrument to identify important sources of variance in rehabilitation outcomes.7 This assumption is supported by results of a stroke rehabilitation comparative effectiveness study: average time spent in physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) per day did not increase percent of variance explained in outcomes, but average time spent in specific PT and OT activities per day did.8

High reviewed effectiveness studies of acute rehabilitation following TBI that described (1) gains made during rehabilitation, (2) effects of early intervention, and (3) effects of intensity of rehabilitation efforts. 9 His conclusions were consistent with those of an NIH Consensus Conference and the Chestnut et al. evidence-based review: persons with TBI unequivocally make functional gains during inpatient rehabilitation–including gains in ambulation, independence, and cognition.7,9,10 However, it was less clear how much these gains can be attributed to specific rehabilitation therapies and interventions and how much should be attributed to age, natural recovery as modified by brain injury severity, and patient pre-injury characteristics. Also, there was insufficient evidence to inform what the timing of interventions should be, what type and intensity of interventions are most appropriate, and for whom specific interventions are most effective.

Inpatient TBI rehabilitation practice remains highly variable, which, in part, reflects lack of empirical evidence of how the complex interweaving of rehabilitation treatments from different professionals, in conjunction with patient prognostic factors (e.g., comorbidities, injury severity), influences recovery. Understanding what treatment factors and processes lead to better outcomes, and for which patient subgroups, would allow development of more effective TBI rehabilitation. However, the information required to gain this understanding is very complex and requires capturing detailed information regarding injury type and severity, the types, timing, and amounts of interventions received, and how these factors affect outcomes across diverse types of patients. A necessary first step in deciphering the content of the “black box” is to develop a comprehensive index of patient prognostic factors that allows for standardized assessment of patient differences in illness and injury severity following TBI. Second, a standard taxonomy of TBI inpatient rehabilitation treatments for each discipline would allow researchers to capture reliably the targets of treatments, the types, intensities, and durations of rehabilitation activities performed, as well as other treatment process factors. We can then identify variance in outcomes, along with those patient and treatment factors that are associated with that variance. The evidence gleaned may be used to inform delivery of future treatment by patient characteristics, design of randomized controlled trials, guide clinical pathways development, or stimulate development of new and innovative treatment approaches.

It is likely that an interaction of interventions and patient factors influences outcomes–that is, what is optimal treatment for one patient subgroup may have no or very limited impact on another group with different needs or abilities to benefit. In rehabilitation, multiple interventions are provided daily by professionals from varied disciplines, backgrounds, and experiences, and nested within rehabilitation facilities with varied customs, cultures, and physical environments. Relatively small effects of a single intervention may be magnified when used in combination with other interventions.11 Interventions that seem effective when studied in isolation may be antagonistic when provided together. In current TBI rehabilitation practice, the large variation in treatments delivered and outcomes produced, between as well as within facilities, affords an opportunity to compare the relative effectiveness of combinations and intensities of interventions among patients with TBI.

Practice-Based Evidence (PBE) study methodology provides an efficient, comprehensive means of implementing comparative effectiveness research.11 The 5-year TBI rehabilitation project described in this paper and in other articles in this supplement used PBE research methodology to isolate specific components of rehabilitation treatments, as has been done in previous PBE rehabilitation inpatient treatment studies.8,12–14 The specific aims of the TBI-PBE project were to: (1) identify individual patient characteristics, including demographic data, severity of brain injury, and severity of illness (complications and comorbidities), that may be associated with significant variation in treatments selected and in outcomes of acute rehabilitation for TBI, (2) identify medical procedures and therapy interventions, alone or in combination, that are associated with better outcomes, controlling for patient characteristics, and (3) determine whether specific treatment interactions with age, severity/impairment, or time are associated with better outcomes.

In this introductory paper, we first provide an overview of the study design, centers, and methods. Second, we briefly describe the primary measures and variables used to describe patients who sustained TBI, with an emphasis on stratification by admission Functional Independence Measure (FIM) Cognitive Scale Score groupings, and the results in our sample. Third, we provide an overview of the point of care forms (POC) incorporating our treatment taxonomy used to capture information on treatments and the most common treatments used by each discipline. Fourth, we describe inpatient rehabilitation outcomes for our sample. Lastly, for the purposes of evaluating generalizability, we compare the project’s US subsample to the US rehabilitation population of persons with TBI.

METHODS

Study Design

The TBI-PBE project was led by the first and second author, with local Co-investigators in the 10 participating centers listed in table 1. The process used was as follows:

Table 1.

Participating Rehabilitation Centers

| Facility | Location |

|---|---|

| Wexner Medical Center* | Columbus, OH |

| Carolinas Rehabilitation, Carolinas HealthCare System* | Charlotte, NC |

| Mount Sinai Medical Center* | New York, NY |

| National Rehabilitation Hospital | Washington, DC |

| Shepherd Center | Atlanta, GA |

| Intermountain Medical Center | Salt Lake City, UT |

| Rush University Medical Center | Chicago, IL |

| Brooks Rehabilitation Hospital | Jacksonville, FL |

| Loma Linda University Rehabilitation Institute | Loma Linda, CA |

| Toronto Rehabilitation Institute | Toronto, Ontario |

TBI Model System center

A multi-center, trans-disciplinary Clinical Project Team was established that was comprised of Co-Investigators (medical director or lead researcher) and leads from each discipline (Rehabilitation Medicine, Nursing, PT, OT, Speech Language Pathology (SLP), Therapeutic Recreation, Social Work, and Neuropsychology) at 9 TBI rehabilitation centers in the US and 1 in Canada. Persons who had sustained a TBI several years prior and family members of persons with TBI were also part of this team. The Clinical Project Team (a) identified and defined all study variables including outcomes of interest, (b) proposed hypotheses for testing, (c) provided leadership and guidance through all phases of data collection and analysis, and (d) contributed to reporting and drawing conclusions. They fostered trans-disciplinary communication and training across traditional scientific and clinical boundaries.

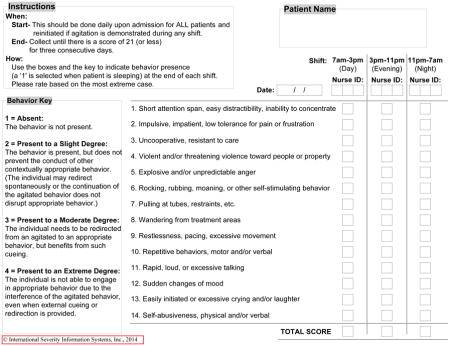

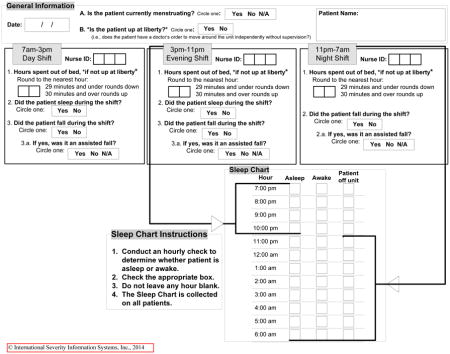

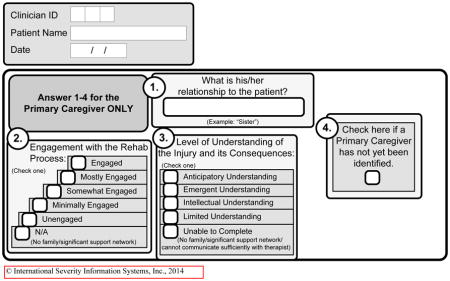

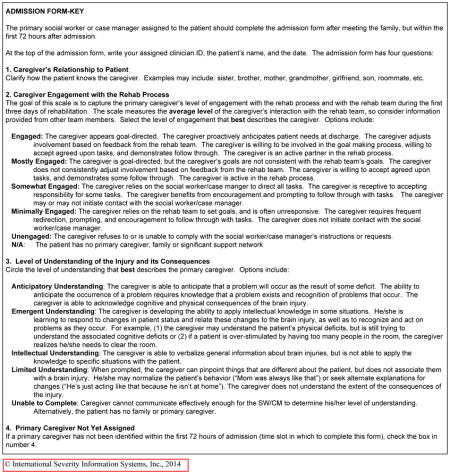

Front-line clinicians developed a TBI Auxiliary Data Module (ADM) to capture detailed patient, process, and outcome data that are found in the patient’s medical record. Many ADM variables had date and time fields so that they could be associated with other variables in time sequence. Examples of variables included in the ADM are demographic data, past medical history, injuries, injury severity, medical comorbidities and complications, rehabilitation interruptions, laboratory findings, vital signs, weight, height, use of restraints, weight bearing restrictions, presence of tracheostomy and gastrostomy tubes, and tube feeding information. Longitudinal data on rehabilitation progress and barriers were collected, including routinely measured functional independence, agitation, sleep, pain, and level of treatment engagement. To take into account each patient’s comorbidities and severity of illness, we used the Comprehensive Severity Index (CSI®) as the primary severity adjustment measure.15–21

Data abstractors at each center were trained to collect ADM data using a web-based software system. These staff attended a 4-day training that included both didactic and practice sessions. After training, we used weekly conference calls of all abstracters to address such issues as how to handle certain chart wording. Chart review occurred after patient discharge and took approximately 4 hours per subject. Reliability monitoring was conducted for abstracters after their first 4 charts were completed and again after 25 charts. Subsequently, reliability testing occurred periodically throughout the years when data were being collected. Charts were selected randomly from completed cases and re-abstracted by a reliability team member. A 95% agreement rate between the abstracter and reliability staff was required for each reliability test. Re-training was performed as needed if the data abstractor did not attain 95% agreement.

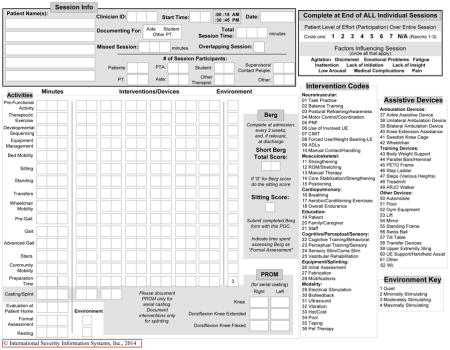

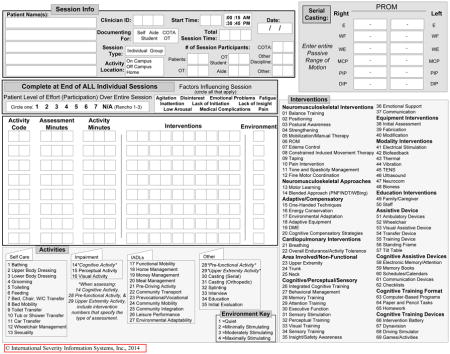

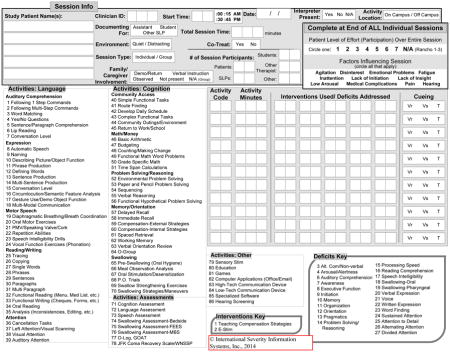

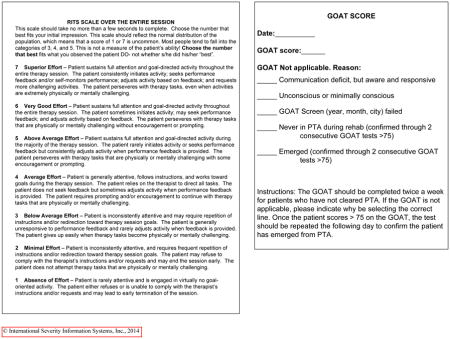

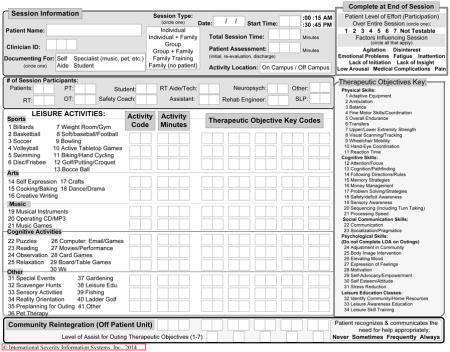

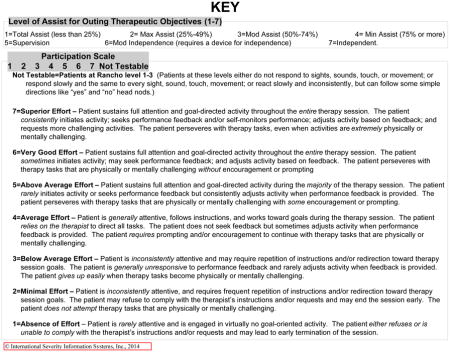

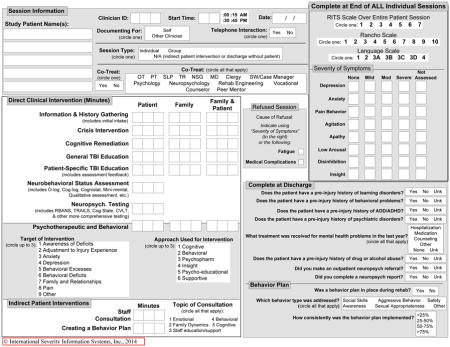

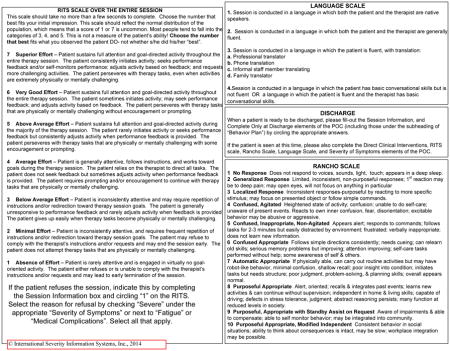

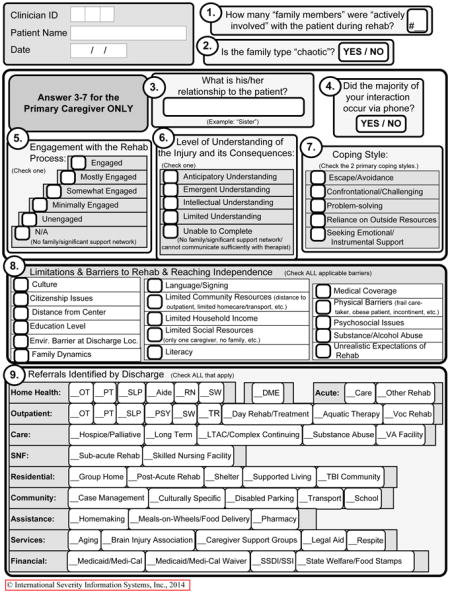

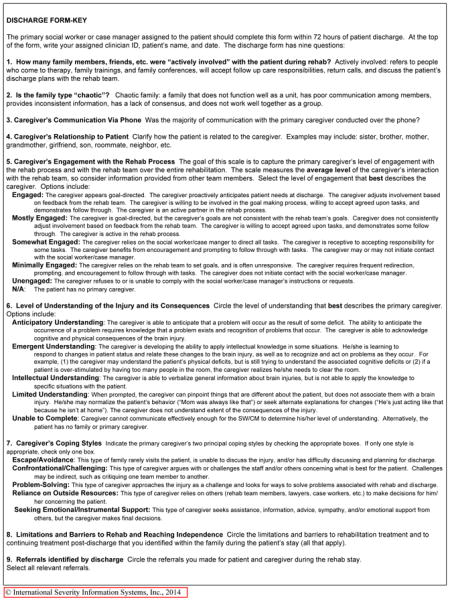

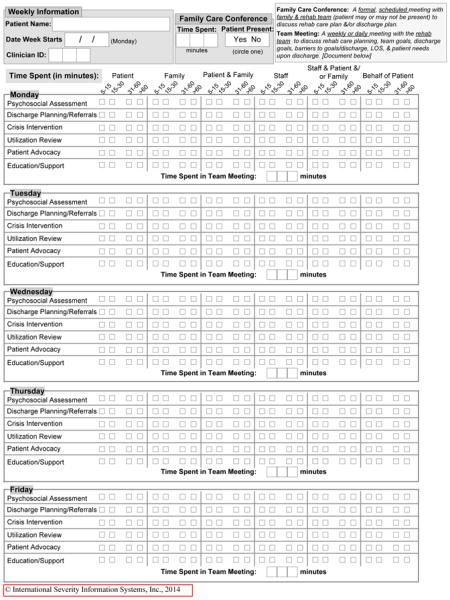

Using weekly conference calls, lead therapists of various disciplines from participating centers engaged in an iterative process to (a) identify and define individual components of each discipline’s care process, (b) create discipline-specific documentation tools to document care processes not detailed in the medical record in order to quantify the delivery of those components (called POC documentation tools used for each therapy session), and (c) incorporate POC documentation into routine facility practices (See Appendix 1 containing POC tools). Clinicians created the POC tools based on their theoretical understanding, research evidence to date, existing guidelines, and their clinical experience. POC forms allowed recording of time spent on specific functional activities (e.g., sitting, transfers, sit-to-stand, pre-gait, gait, advanced gait, community mobility, etc. in PT).22

The Lead Therapist in each participating discipline at each center underwent extensive training using POC training materials established by the project team. Train-the-trainer sessions were held for Lead Therapists who conducted subsequent discipline-specific training programs for their colleagues to teach them how to use the POC documentation. In total, over 950 therapists were trained. During the 30 months of data collection, weekly discipline-specific conference calls of the Lead Therapists were held to address questions concerning documentation and ensure consistent POC data completion across centers. To check reliability, periodically clinicians were given case scenarios and asked to complete POC documentation based on the scenarios. Agreement with the answer key was measured and aggregated results for each discipline in each center were reported back to the center. Clinician-specific problems were identified, and if necessary, additional training was held if agreement was <90%. Each therapy session was documented by the treating therapist after the patient encounter. Group therapy was recorded and included documentation of the number of patients, therapists, and assistants involved in the group. Nurses documented pain, sleep, and agitation during each shift. Hardcopy POC information was entered into a web-based data collection system by research assistants.

Medication administration data were downloaded from center electronic medical record systems into the centralized research database.

Staff from each center was trained on how to track patients for follow-up after leaving inpatient care, as well as how to conduct follow-up interviews. Protocols used by the TBI Model Systems for tracking and interviewing were adapted for the study;23 training was conducted by experienced TBI Model Systems researchers. The TBI Model Systems protocol for interviewing the “best source” of information—patient or proxy—was used in this study. Follow-up phone interviews with patients or their proxies were conducted at 3 and 9 months post-discharge, using a +/− 1-month window.

Short surveys (provider profiles) were used to collect information on clinician training and experience at each site. In addition, local investigators completed a facility survey with questions about structures and processes in the brain injury rehabilitation unit (See TBI-PBE study facility descriptions in this issue).24

Using site and patient ID the data center merged these data from multiple sources to create a patient-level database with all the data elements over the course of each patient’s rehabilitation stay and follow-up interviews.

Data were checked for completeness and accuracy (e.g., sensible value entries such as dates within the study time period and sequential timing of linked process steps or unrealistic values and obvious outliers). Data were cleaned before analysis was started.

Study Sample

Ten participating rehabilitation centers enrolled all consenting eligible patients admitted to their specialty brain injury unit, resulting in a consecutive sample of adolescents and adults with TBI receiving inpatient rehabilitation between October 2008 and September 2011 (overall 82.5% of patients consented). We chose to include sites in the US as well as Canada in order to study a broad range of patient characteristics and treatment practices. The Institutional Review Board at each study center approved the study; each patient or his/her proxy gave informed consent.

The final study sample was 2130 patients (586 females and 1544 males; 113 between age 14 and 18) treated over 2.5 years. Inclusion criteria were:

Age over 14 years

Sustained a TBI, defined as damage to brain tissue caused by external force and evidenced by loss of consciousness, post-traumatic amnesia (PTA), skull fracture, or objective neurological findings

-

TBI was characterized with an International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) code consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines for Surveillance of Central Nervous System Injury:1

800.0–801.9 – Fracture of the vault or base of the skull

803.0–804.9 – Other and unqualified multiple fractures of the skull

850.0–854.1 – Intracranial injury, including concussion, contusion, laceration, and hemorrhage

873.0–873.9 – Other open wound to the head

905.0 – Late effects of fracture of the skull and face

907.0 – Late effects of intracranial injury without mention of skull fracture

959.01 – Head injury, unspecified

Received their first, complete inpatient care on the designated adult brain injury rehabilitation unit

Functional severity

The FIM, used as a measure of the severity of functional deficits upon entry into treatment, consists of 18 items in two domains: Motor (13 items) and Cognitive-communicative (5 items). Each item is rated on a 7-category scale, ranging from 1: total assistance, to 7: complete independence. To eliminate distortion in quantifying the status of patients whose capability is at the extremes of the instrument’s range, the Motor and Cognitive subscores were recoded separately using tables published by Heinemann et al. that were based on Rasch analysis of data of a large brain injury sample.25

Comorbidity

CSI, developed over a period of 30 years, defines severity as the physiologic and psychological complexity presented to medical personnel due to the extent and interactions of a patient’s injury(s) and disease(s). CSI is age- and disease-specific, and is independent of treatments. It provides an objective, consistent method to operationalize patient severity of illness based on over 2,100 individual signs, symptoms, and physical findings and over 5,600 disease-specific criteria sets related to all of a patient’s injury(s) and disease(s), not just on diagnostic information (ICD-9-CM coding) included in a discharge summary. CSI has been validated extensively in inpatient, ambulatory, rehabilitation, and long-term care studies since 1982.15–21

The CSI modification used in the present study allowed separation of severity of brain injury from severity of illness resulting from all other injuries, complications, and comorbidities. This use of CSI allowed detection of patient brain dysfunction differences that might otherwise be hidden or “washed out” by the effect of an overall injury severity score. Some criteria included in the brain CSI component were amount of intracranial bleeding, length of PTA, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), amount of compression, hydrocephalus, pupil reaction, etc.

CSI scores were calculated for three time spans of the patient’s stay in rehabilitation:

Admission CSI is based on all information available for the first 72 hours of the rehabilitation stay. It assesses how sick the patient was on admission to the rehabilitation facility.

Discharge CSI reflects information from the last 72 hours before discharge.

Maximum CSI uses information from the entire stay, including the admission and discharge periods. It measures the most aberrant findings, regardless of when they occurred.

Patient Variables

Variables describing patient characteristics, including demographics and injury characteristics, are included in table 2 overall and by admission FIM Cognitive subgroup.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics by Admission FIM Cognitive Score Subgroup

| Characteristics | Admission FIM Cognitive Score* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=2130) | <=6 (n=339) | 7–10 (n=374) | 11–15 (n=495) | 16–20 (n=408) | >=21 (n=504) | P | |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Male (%) | 72.5 | 71.7 | 76.5 | 75.8 | 71.3 | 67.7 | 0.018 † |

| Age at rehabilitation admission (mean, SD) | 44.5 (21.3) | 43.0 (21.9) | 42.3 (20.0) | 43.1 (20.9) | 46.9 (21.6) | 46.8 (21.8) | <.001 ‡ |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | 0.083 † | ||||||

| Black | 15.1 | 15.3 | 13.9 | 16.8 | 15.4 | 13.9 | |

| White non Hispanic | 74.4 | 77.9 | 73.5 | 73.5 | 74.3 | 73.4 | |

| White Hispanic | 6.2 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 5.7 | 6.6 | 5.8 | |

| Other and unknown§ | 4.4 | 1.8 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 6.9 | |

| Highest education achieved (%) | 0.008 † | ||||||

| Some high school, no diploma | 23.0 | 20.4 | 26.2 | 25.3 | 26.5 | 17.5 | |

| High school diploma | 25.9 | 25.1 | 27.5 | 28.1 | 25.7 | 22.6 | |

| Work towards or completed Associate’s degree | 16.2 | 15.9 | 13.9 | 14.9 | 17.9 | 18.1 | |

| Work towards or completed Bachelor’s degree | 19.7 | 21.2 | 20.3 | 18.8 | 15.9 | 22.0 | |

| Work towards or completed Master’s/Doctoral degree | 9.7 | 11.5 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 12.1 | |

| Unknown | 5.7 | 5.9 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 7.7 | |

| Marital status prior to injury (%) | 0.267 † | ||||||

| Single/never married | 42.6 | 43.7 | 44.9 | 44.8 | 38.2 | 40.9 | |

| Married/common law | 36.5 | 36.3 | 35.6 | 35.8 | 37.0 | 37.9 | |

| Previously married | 17.5 | 16.2 | 15.5 | 16.2 | 22.5 | 17.1 | |

| Other/unknown || | 3.5 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 4.2 | |

| Occupation prior to injury (%) | 0.006 † | ||||||

| Employed and student | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 4.4 | |

| Employed only | 47.1 | 45.4 | 48.4 | 47.5 | 43.9 | 49.4 | |

| Unemployed | 13.3 | 13.6 | 15.8 | 13.7 | 14.2 | 10.3 | |

| Retired | 23.1 | 20.9 | 17.9 | 21.0 | 28.4 | 26.4 | |

| Student only | 11.4 | 13.6 | 12.0 | 12.7 | 9.6 | 9.3 | |

| Unknown | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.2 | |

| Able to drive before injury (%) | 0.128 † | ||||||

| Yes | 73.1 | 70.2 | 75.7 | 75.6 | 69.9 | 73.0 | |

| No | 10.8 | 9.4 | 10.7 | 9.5 | 13.9 | 10.5 | |

| Unknown | 16.1 | 20.4 | 13.6 | 14.9 | 16.2 | 16.5 | |

| Primary payer (%) | <.001 † | ||||||

| Medicare | 19.4 | 18.0 | 15.0 | 18.4 | 23.0 | 22.2 | |

| Medicaid | 15.5 | 20.9 | 18.2 | 16.4 | 17.2 | 7.7 | |

| Private insurance | 24.5 | 26.3 | 24.6 | 30.1 | 24.0 | 17.9 | |

| Centralized (single payer system) | 6.9 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 6.4 | 20.2 | |

| Worker’s compensation | 6.8 | 5.9 | 8.6 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 6.5 | |

| Self pay | 2.2 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | |

| MCO/HMO | 14.3 | 13.9 | 18.4 | 14.1 | 13.2 | 12.3 | |

| No-fault auto insurance | 4.5 | 7.1 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 5.8 | |

| None | 2.4 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.8 | |

| Other/unknown | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.0 | |

| Secondary payer (%) | <.001 † | ||||||

| Medicare | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 1.4 | |

| Medicaid | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 3.2 | |

| Private insurance | 12.7 | 14.5 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 14.2 | 17.3 | |

| Worker’s compensation | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | |

| Self pay | 3.4 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 2.9 | 2.6 | |

| MCO/HMO | 2.4 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 2.4 | |

| No-fault auto insurance | 6.7 | 8.9 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 6.5 | |

| None | 42.0 | 51.0 | 45.2 | 42.1 | 38.0 | 36.9 | |

| Other/unknown | 26.7 | 14.5 | 28.3 | 29.1 | 29.4 | 29.0 | |

| Admission body mass index (%) | <.001 † | ||||||

| <16 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.4 | |

| 16–<=18.5 | 8.5 | 11.8 | 11.0 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 5.2 | |

| >18.5–<=25 | 49.7 | 55.5 | 55.1 | 50.5 | 46.3 | 43.1 | |

| >25–<=30 | 23.6 | 18.0 | 18.7 | 25.1 | 26.5 | 27.6 | |

| >30–<=35 | 7.9 | 6.5 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 8.3 | 9.1 | |

| >35–<=40 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 3.6 | |

| >40 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 2.4 | |

| Unknown | 5.3 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 6.9 | 8.7 | |

| Pre-existing and co-existing conditions | |||||||

| History of alcohol use before injury (%) | 44.6 | 38.3 | 50.0 | 48.1 | 44.6 | 41.1 | 0.005 † |

| Alcohol use at time of injury (%) | 19.1 | 18.6 | 17.4 | 20.2 | 20.1 | 18.5 | 0.816 † |

| History of alcohol abuse before injury (%) | 35.6 | 30.4 | 36.9 | 39.0 | 37.3 | 33.7 | 0.091 † |

| History of drug abuse before injury (%) | 20.5 | 17.7 | 22.5 | 20.8 | 25.0 | 17.1 | 0.024 † |

| Drug abuse at time of injury (%) | 6.4 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 5.9 | 6.9 | 4.6 | 0.217 † |

| ADHD (%) | 7.6 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 7.9 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 0.799 † |

| Anxiety (%) ¶ | 40.9 | 32.5 | 46.5 | 45.3 | 41.4 | 37.5 | <.001 † |

| CAD (%) | 8.9 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 10.3 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 0.166 † |

| CHF (%) | 3.7 | 1.8 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 0.235 † |

| Depression (%) ¶ | 48.9 | 47.5 | 52.9 | 54.1 | 49.8 | 41.1 | <.001 † |

| Diabetes (%) | 16.8 | 21.2 | 15.2 | 21.0 | 14.2 | 12.9 | <.001 † |

| Hypertension (%) | 43.5 | 46.6 | 41.7 | 44.8 | 45.3 | 39.9 | 0.246 † |

| Paralysis (%) | 38.0 | 47.5 | 45.5 | 43.6 | 30.2 | 26.8 | <.001 † |

| Renal failure (%) | 8.4 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 8.7 | 0.989 † |

| Previous brain injury (%) | 8.9 | 5.6 | 7.2 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 8.9 | 0.023 † |

| Number of previous brain injuries (mean, SD) # | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.2 (0.5) | 0.649 † |

| Tracheotomy or ventilation on admission (%) | 22.1 | 51.0 | 34.0 | 22.2 | 7.6 | 5.4 | <.001 † |

| Brain injury and severity information | |||||||

| Cause of injury (%) | 0.001 † | ||||||

| Fall | 31.9 | 28.0 | 26.2 | 30.1 | 35.0 | 38.3 | |

| Motor vehicle crash | 55.6 | 63.7 | 57.8 | 57.2 | 52.5 | 49.2 | |

| Sports | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 2.4 | |

| Violence | 7.0 | 4.4 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 7.1 | 7.1 | |

| Miscellaneous | 3.6 | 2.7 | 5.9 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.0 | |

| GCS score immediately after injury or upon arrival in acute care (%) | <.001 † | ||||||

| Mild (13–15) | 14.7 | 6.8 | 9.1 | 11.1 | 17.9 | 25.6 | |

| Moderate (9–12) | 7.7 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 8.3 | 7.6 | 12.1 | |

| Severe (3–8) | 32.3 | 46.0 | 42.0 | 35.4 | 24.5 | 18.8 | |

| Intubated/sedated | 12.2 | 12.4 | 15.0 | 11.7 | 13.7 | 8.7 | |

| Unknown | 33.0 | 30.7 | 29.1 | 33.5 | 36.3 | 34.7 | |

| Nature of brain injury (%) | 0.045 † | ||||||

| Skull closed, contusion/hemorrhage present | 71.1 | 74.9 | 72.7 | 69.7 | 71.6 | 68.8 | |

| Skull closed, no contusion/hemorrhage | 21.6 | 15.3 | 19.5 | 24.0 | 21.6 | 24.6 | |

| Skull open, contusion/hemorrhage present | 7.3 | 9.7 | 7.8 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 6.5 | |

| Facial fracture (%) | 13.6 | 10.3 | 16.8 | 14.3 | 15.9 | 10.9 | 0.020 † |

| Skull fracture (%) | 26.8 | 25.1 | 32.6 | 28.3 | 25.7 | 23.0 | 0.022 † |

| Brain injury location (%) | 0.034 † | ||||||

| Bilateral brain involvement | 64.2 | 64.9 | 68.7 | 61.8 | 64.7 | 62.3 | |

| Left brain involvement only | 18.4 | 22.4 | 16.3 | 20.0 | 16.4 | 17.3 | |

| Right brain involvement only | 17.5 | 12.7 | 15.0 | 18.2 | 18.9 | 20.4 | |

| Midline shift (%) | <.001 † | ||||||

| No midline shift | 30.5 | 22.4 | 23.8 | 26.5 | 35.8 | 40.9 | |

| >0–<=5 mm of midline shift | 12.4 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 10.9 | |

| >5 mm of midline shift | 12.1 | 13.9 | 17.4 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 8.5 | |

| Midline shift, mm not specified | 11.1 | 15.3 | 9.1 | 10.7 | 9.6 | 11.5 | |

| Unknown | 33.9 | 34.8 | 36.1 | 39.0 | 31.1 | 28.2 | |

| Subdural hematoma (%) | 46.8 | 49.3 | 52.1 | 46.5 | 45.6 | 42.9 | 0.075 † |

| Epidural hematoma (%) | 8.2 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 6.4 | 7.9 | 0.672 † |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (%) | 59.2 | 71.1 | 65.0 | 58.2 | 55.1 | 51.0 | <.001 † |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage (%) | 18.6 | 29.2 | 23.8 | 18.0 | 14.2 | 11.7 | <.001 † |

| Brain stem involved at injury (%) | 5.7 | 7.7 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 0.362 † |

| Craniotomy during care episode (%) | 20.3 | 18.6 | 24.1 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 18.5 | 0.289 † |

| Craniectomy during care episode (%) | 7.2 | 12.7 | 9.6 | 6.9 | 2.9 | 5.4 | <.001 † |

| Weight bearing precaution during rehabilitation (%) | 26.0 | 25.1 | 24.3 | 21.8 | 30.4 | 27.8 | 0.038 † |

| Days from injury to rehabilitation admission (mean, SD) | 29.3 (34.3) | 36.5 (38.7) | 34.2 (37.6) | 27.5 (32.3) | 26 (33.5) | 24.9 (30.1) | <.001 ‡ |

| Brain injury component of admission CSI score (mean, SD) | 44.7 (23.7) | 71.4 (19.3) | 62 (17.6) | 47.7 (14.3) | 33.2 (12.6) | 19.7 (10.0) | <.001 ‡ |

| Non-brain injury component of admission CSI score (mean, SD) | 16.9 (15.0) | 19.1 (16.1) | 20.3 (15.2) | 18.1 (14.7) | 16.1 (15.7) | 12.2 (11.9) | <.001 ‡ |

| Moderate to severe dysphagia on admission (%) | 53.4 | 89.1 | 75.4 | 56.4 | 36.0 | 23.4 | <.001 † |

| Moderate to severe aphasia on admission (%) | 46.5 | 74.3 | 68.2 | 50.3 | 37.3 | 15.1 | <.001 † |

| Moderate to severe ataxia on admission (%) | 15.4 | 21.8 | 21.4 | 17.0 | 12.7 | 6.5 | <.001 † |

| Functional indepedence measures | |||||||

| Admission FIM motor score - untransformed (mean, SD) | 34.7 (19.7) | 17.3 (8.8) | 24.0 (13.1) | 33.5 (16.2) | 40.8 (16.4) | 50.8 (20.0) | <.001 ‡ |

| Admission FIM motor score - Rasch transformed (mean, SD) | 33.2 (19.3) | 11.5 (14.5) | 23.2 (16.4) | 34.2 (14.8) | 40.5 (12.5) | 48.3 (15.2) | <.001 ‡ |

| Admission FIM cognitive score - untransformed (mean, SD) | 14.8 (7.2) | 5.3 (0.4) | 8.6 (1.1) | 13.1 (1.4) | 17.9 (1.4) | 24.9 (3.3) | <.001 ‡ |

| Admission FIM cognitive score - Rasch transformed (mean, SD) | 37.2 (19.5) | 2.5 (4.4) | 25.7 (4.8) | 38.4 (3.0) | 47.5 (2.4) | 59.6 (7.7) | <.001 ‡ |

NOTE: Abbreviations: MCO/HMO, Managed care organization/Health maintainance organization; CHF, Congestive heart failure; CAD, Coronary artery disease; ADHD, Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; CSI, Comprehensive Severity Index;

n=10 patients missing admission FIM cognitive score.

Chi-Square analysis.

Analysis of variance test.

Miscellaneous includes 69 Asians, 8 Native Americans, 7 Pacific Islanders, and 3 with unknown race.

Other/unknown includes 62 Separated status, 2 listed as Significant Other, and 10 with unknown or missing status.

Includes symptoms existing during rehab.

Data include only patients who had previous brain injury before the current injury requiring rehabilitation.

Process Variables

As described above, we collected process variables in two ways: from therapy intervention POC forms and from chart review (ADM). Table 3 provides a selection of relevant findings. It also includes clinician experience calculated for the “average” clinician within a discipline who saw the patient as follows: Clinician experience index = ((sum of minutes by clinician #1 * years experience of clinician #1) + (sum of minutes by clinician #2 * years experience of clinician #2) + (etc))/(total minutes with included clinicians).

Table 3.

Rehabilitation Treatments by Admission FIM Cognitive Score Subgroup

| Characteristics | Admission FIM Cognitive Score* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=2130) | <=6 (n=339) | 7–10 (n=374) | 11–15 (n=495) | 16–20 (n=408) | >=21 (n=504) | P | |

| Selected non-therapy treatments | |||||||

| Restraints used (%) † | 56.7 | 85.0 | 76.5 | 64.2 | 44.9 | 25.0 | <.001 ‡ |

| Number of days of restraint use (mean, SD)§ | 23.8 (20.6) | 32.9 (29.1) | 27.6 (19.2) | 21.4 (15.0) | 16.6 (12.9) | 11.2 (8.7) | <.001 || |

| Sitter used (%) | 20.6 | 33.9 | 28.1 | 23.6 | 16.4 | 6.6 | <.001 ‡ |

| Number of days of sitter use (mean, SD)§ | 14.9 (14.9) | 22.2 (19.2) | 15.3 (13.9) | 11.2 (10.1) | 10.0 (8.4) | 11.0 (16.8) | <.001 || |

| Enteral nutrition (%) | 36.1 | 77.6 | 58.3 | 35.8 | 15.9 | 8.3 | <.001 ‡ |

| Number of days of enteral nutrition (mean, SD)§ | 20.3 (17.9) | 26.6 (20.1) | 19.5 (15.4) | 15.9 (17.6) | 12.9 (10.0) | 11.9 (12.4) | <.001 || |

| Parenteral nutrition adminstered (%) | 6.1 | 13.9 | 9.4 | 6.1 | 2.5 | 0.8 | <.001 ‡ |

| Medications | |||||||

| Medications administered (%) | |||||||

| Analgesic narcotic/opioid | 74.3 | 75.9 | 75.9 | 74.5 | 75.9 | 70.2 | 0.214 ‡ |

| Analgesic non-narcotic | 80.2 | 87.0 | 83.2 | 80.7 | 78.6 | 74.4 | <.001 ‡ |

| Anticholinergic | 52.4 | 76.5 | 61.0 | 48.1 | 46.3 | 38.7 | <.001 ‡ |

| Anticoagulant | 72.1 | 85.2 | 80.5 | 78.4 | 68.7 | 53.8 | <.001 ‡ |

| Anticonvulsant | 50.1 | 54.8 | 53.4 | 49.8 | 49.5 | 44.6 | 0.033 ‡ |

| Antidepressant | 69.2 | 81.3 | 77.8 | 69.3 | 69.9 | 53.8 | <.001 ‡ |

| Antiulcer | 73.9 | 83.4 | 80.8 | 77.4 | 73.9 | 58.8 | <.001 ‡ |

| Trazadone | 54.8 | 68.1 | 65.9 | 56.6 | 52.2 | 37.5 | <.001 ‡ |

| Therapy activities | |||||||

| % of study population receiving any PT | 99.3 | 100.0 | 99.7 | 99.0 | 99.5 | 98.8 | 0.172 ‡ |

| Total minutes/week (mean, SD)§ | 314.2 (109.5) | 343.8 (95.0) | 319.2 (98.8) | 308.7 (98.5) | 304.9 (115.0) | 303.3 (127.6) | <.001 || |

| % of study population receiving any OT | 99.2 | 99.7 | 99.5 | 99.2 | 99.5 | 98.4 | 0.212 ‡ |

| Total minutes/week (mean, SD)§ | 298.1 (101.3) | 321.8 (89.6) | 304.5 (88.4) | 299.3 (92.1) | 283.9 (107.9) | 287.5 (117.1) | <.001 || |

| % of study population receiving any speech language pathology | 96.7 | 100.0 | 98.9 | 98.4 | 97.3 | 90.7 | <.001 ‡ |

| Total minutes/week (mean, SD)§ | 253.6 (114.9) | 268 (108.1) | 290.5 (99.7) | 281.5 (109.4) | 239.9 (107.8) | 194.2 (118.8) | <.001 || |

| % of study population receiving any psychology | 75.2 | 71.4 | 82.1 | 84.0 | 77.7 | 61.7 | <.001 ‡ |

| Total minutes/week (mean, SD)§ | 85 (82.0) | 56.5 (62.0) | 71.7 (62.3) | 97.6 (75.8) | 92.2 (91.8) | 96.3 (101.9) | <.001 || |

| % of study population receiving any recreational therapy | 72.0 | 71.7 | 78.6 | 82.2 | 71.8 | 57.3 | <.001 ‡ |

| Total minutes/week (mean, SD)§ | 91.6 (71.2) | 66.4 (50.5) | 87.6 (62.4) | 105 (79.8) | 102.5 (71.8) | 87 (75.1) | <.001 || |

| % of study population receiving any social work/case management services | 84.1 | 89.1 | 82.1 | 83.6 | 84.3 | 82.3 | 0.069 ‡ |

| Total minutes/week (mean, SD)§ | 118.5 (74.7) | 101.3 (64.2) | 106.1 (73.3) | 117.6 (66.8) | 126.3 (72.5) | 133.7 (87.5) | <.001 || |

| PT activities (Three most frequently used) | |||||||

| Theraputic exercise | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 95.0 | 98.2 | 97.3 | 94.9 | 94.1 | 91.7 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 56 (41.9) | 50.7 (35.0) | 45 (33.0) | 49 (37.9) | 59.2 (40.3) | 73.5 (51.6) | <.001 || |

| Gait training | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 88.2 | 89.7 | 92.8 | 90.3 | 88.7 | 81.2 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 80.6 (70.3) | 92.4 (71.7) | 75.4 (61.4) | 75 (61.0) | 77 (68.4) | 86.1 (85.1) | 0.002 || |

| Standing | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 83.8 | 95.3 | 94.4 | 87.3 | 78.4 | 69.0 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 31.4 (23.2) | 33.5 (22.1) | 31.4 (20.7) | 31.3 (22.6) | 30.2 (25.8) | 30.5 (24.7) | 0.411 || |

| OT activities (Three most frequently used) | |||||||

| Cognitive activity | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 91.2 | 97.3 | 95.5 | 92.3 | 90.7 | 82.9 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 68.9 (61.4) | 83 (67.7) | 66.1 (57.5) | 66.2 (60.1) | 65.3 (58.3) | 67.1 (62.9) | <.001 || |

| Lower body dressing | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 82.0 | 92.9 | 95.7 | 86.7 | 79.7 | 61.5 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 16.5 (12.9) | 17.3 (11.7) | 16.1 (11.5) | 14.9 (11.3) | 16.7 (13.6) | 18 (16.4) | 0.014 || |

| Upper extremity activity | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 79.6 | 92.9 | 84.5 | 82.6 | 76.7 | 66.3 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 49.1 (42.4) | 46.2 (40.4) | 47.2 (36.9) | 43.8 (35.6) | 51.2 (40.4) | 57.7 (55.6) | <.001 || |

| Speech language pathology activities (Three most frequently used): | |||||||

| Education | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 72.4 | 79.4 | 79.9 | 79.0 | 70.8 | 56.7 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 17.9 (14.1) | 13.2 (12.3) | 15.5 (11.7) | 18.9 (13.7) | 20.2 (13.9) | 21.3 (17.1) | <.001 || |

| Verbal reasoning | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 62.6 | 63.7 | 65.5 | 74.9 | 66.7 | 44.8 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 19.8 (18.0) | 11.6 (10.9) | 18.4 (16.3) | 22.6 (19.4) | 21.1 (19.2) | 23 (19.1) | <.001 || |

| Verbal orientation review | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 59.6 | 87.6 | 84.0 | 70.7 | 45.1 | 22.8 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 19.6 (18.2) | 22.7 (19.9) | 23.3 (19.6) | 18.2 (17.2) | 14.6 (13.3) | 12.1 (11.8) | <.001 || |

| Psychology activities (Three most frequently used): | |||||||

| Neurobehavioral assessment | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 57.3 | 55.5 | 67.1 | 69.3 | 56.4 | 40.1 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 19.2 (16.9) | 18.3 (18.2) | 21.4 (16.2) | 20.3 (14.6) | 17.1 (20.7) | 17.8 (15.4) | 0.023|| |

| Psychotherapeutic and behavior intervention | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 44.6 | 37.8 | 50.5 | 55.4 | 46.6 | 31.9 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 22.6 (22.0) | 14.5 (14.0) | 18.7 (16.6) | 24.6 (20.0) | 24.8 (22.8) | 28 (31.1) | <.001 || |

| Neuropsychological testing | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 38.5 | 23.9 | 36.6 | 53.1 | 43.1 | 31.5 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 38.5 (36.9) | 19.5 (16.9) | 27.6 (21.3) | 40.8 (32.4) | 39.5 (34.1) | 52.7 (54.5) | <.001 || |

| Recreational therapy activities (Three most frequently used): | |||||||

| Board/table top games | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 31.8 | 32.7 | 34.0 | 38.4 | 34.3 | 21.2 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 25.3 (23.1) | 14.3 (12.9) | 21.1 (19.0) | 23.1 (21.4) | 31.5 (22.8) | 38.1 (30.4) | <.001 || |

| Card games | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 27.5 | 28.9 | 33.2 | 31.3 | 31.6 | 15.5 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 29 (28.3) | 15.7 (15.0) | 25.8 (27.7) | 30.3 (29.0) | 36.9 (31.7) | 35.8 (28.7) | <.001 || |

| Community reintegration | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 24.4 | 26.5 | 27.8 | 33.9 | 21.8 | 12.5 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 57.9 (47.2) | 29.9 (22.6) | 46.9 (32.2) | 63.5 (47.0) | 66.1 (43.0) | 92.2 (69.4) | <.001 || |

| Social work/case management activities (Three most frequently used): | |||||||

| Team meetings | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 80.3 | 87.9 | 79.9 | 82.6 | 79.2 | 74.0 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 10.4 (6.4) | 9.6 (5.3) | 10.6 (6.3) | 10.4 (5.8) | 10.2 (6.2) | 10.9 (7.9) | 0.158 || |

| Discharge planning for patient | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 68.0 | 76.4 | 69.0 | 67.5 | 67.6 | 62.5 | 0.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 21.3 (20.7) | 15 (17.8) | 18.7 (17.1) | 21.2 (19.1) | 22.7 (20.9) | 28 (25.0) | <.001 || |

| Education/support for family | |||||||

| % patients receiving | 54.5 | 75.8 | 58.3 | 56.2 | 51.2 | 38.1 | <.001 ‡ |

| Minutes per week (mean, SD)§ | 18 (16.9) | 16.1 (16.3) | 18.6 (17.8) | 19.2 (17.4) | 19.9 (18.9) | 15.6 (12.5) | 0.021 || |

| Therapist experience | |||||||

| Clinician Experience Index in years (mean, SD) | |||||||

| Overall | 4.8 (3.1) | 4.6 (3.3) | 4.3 (2.6) | 4.6 (2.8) | 5.2 (3.6) | 5.0 (3.0) | <.001 || |

| Physical therapy | 4.0 (4.4) | 3.8 (4.0) | 3.8 (4.7) | 3.7 (3.9) | 4.4 (4.7) | 4.2 (4.9) | 0.143 || |

| Occupational therapy | 3.1 (3.0) | 3.3 (2.9) | 2.8 (2.6) | 2.9 (2.9) | 2.9 (3.0) | 3.6 (3.5) | <.001 || |

| Speech language pathology | 5.1 (3.1) | 4.7 (2.9) | 4.8 (3.1) | 4.8 (3.1) | 5.4 (3.1) | 5.7 (3.3) | <.001 || |

| Recreational therapy | 1.9 (2.1) | 1.7 (2.0) | 1.8 (2.1) | 1.8 (2.2) | 1.8 (2.0) | 2.1 (2.3) | 0.380 || |

| Psychology | 4.5 (5.3) | 4.9 (5.6) | 4.3 (4.6) | 4.3 (4.6) | 5.1 (6.3) | 4.2 (5.6) | 0.326 || |

| Social work | 8.7 (9.0) | 8.9 (8.9) | 8.2 (8.4) | 9.1 (9.4) | 9.3 (9.9) | 8.3 (8.1) | 0.491 || |

NOTE:

n=10 patients missing admission FIM cognitive score.

Restraint types include: posey rolls and vests, posey Swedish locking belt-beds, abdominal binders, bed alarms, bed side rails, bed nets/enclosures, cameras, bed, lap and, seat belts, mitts, limb holders, and wander guards.

Chi-Square analysis.

Data include only patients who had the specified treatment.

Analysis of variance test.

Rehabilitation Course Variables

Besides the patient data available on admission, we collected additional variables that describe the patients during the course of their rehabilitation unit stay using the ADM. These include descriptions of aphasia, dysphagia, ataxia, PTA (based on neuropsychologists’ ratings on one of two analogous standardized assessments, i.e., the Orientation Log and the Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test), pain, agitation, sleep, and falls. Table 4 provides information on these data elements.

Table 4.

Events and Patient Characteristics during Rehabilitation by Admission FIM Cognitive Score Subgroup

| Characteristics | Admission FIM Cognitive Score* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=2130) | <=6 (n=339) | 7–10 (n=374) | 11–15 (n=495) | 16–20 (n=408) | >=21 (n=504) | P | |

| Severity information | |||||||

| Maximum brain injury component of CSI score (mean, SD) | 48.4 (24.8) | 77.2 (18.3) | 66.8 (16.6) | 50.8 (15.6) | 36.1 (13.3) | 22 (10.2) | <.001 † |

| Maximum non-brain injury component of CSI score (mean, SD) | 24.8 (20.9) | 30.6 (23.5) | 30.7 (21.7) | 25.8 (20.7) | 22.7 (20.3) | 16.8 (15.4) | <.001 † |

| Moderate/severe dysphagia (%) | 54.0 | 90.0 | 76.2 | 56.8 | 37.0 | 23.6 | <.001 ‡ |

| Moderate/severe aphasia (%) | 47.8 | 76.4 | 69.3 | 50.9 | 38.7 | 16.5 | <.001 ‡ |

| Moderate/severe ataxia (%) | 15.9 | 23.6 | 21.7 | 17.2 | 13.2 | 6.5 | <.001 ‡ |

| Days from injury to clearing PTA (mean, SD) | 37.6 (42.7) | 70.7 (54.4) | 56.4 (45.9) | 35.6 (36.1) | 19.9 (23.1) | 10.6 (14.0) | <.001 ‡ |

| Time of PTA clearance (%) | <.001 ‡ | ||||||

| Prior to rehabilitation | 42.2 | 2.1 | 8.3 | 27.9 | 66.2 | 89.1 | |

| During rehabilitation | 34.3 | 44.5 | 48.4 | 49.7 | 26.2 | 8.3 | |

| After rehabilitation discharge | 23.5 | 53.4 | 43.3 | 22.4 | 7.6 | 2.6 | |

| Days from rehabilitation admission to clearing PTA (for patients who cleared PTA during rehabilitation) | 15.6 (13.5) | 25.2 (16.9) | 17.9 (13.7) | 12.4 (9.9) | 8.9 (7.2) | 7.4 (5.0) | <.001 ‡ |

| Pain, agitation, and falls | |||||||

| Pain (mean, SD) | |||||||

| Percent of days with pain score >=1 | 38.3 (32.8) | 26.2 (23.8) | 32.2 (27.8) | 39.3 (32.6) | 43.3 (34.7) | 45.6 (36.9) | <.001 ‡ |

| Percent of days with pain score >=3 | 32.9 (32.6) | 18.6 (21.2) | 26.8 (27.1) | 35.0 (32.2) | 39.3 (34.7) | 39.8 (37.4) | <.001 ‡ |

| Percent of days with pain score >=5 | 27.9 (30.9) | 14.1 (18.3) | 21.7 (24.9) | 30.2 (30.5) | 34.3 (33.4) | 34.3 (35.8) | <.001 ‡ |

| Percent of days with pain score >=7 | 17.2 (25.3) | 7.0 (12.5) | 11.5 (18.3) | 18.1 (24.1) | 24.2 (30.2) | 21.6 (29.8) | <.001 ‡ |

| Average high pain score § | 4.6 (2.8) | 4.0 (2.7) | 4.6 (2.6) | 5.0 (2.6) | 5.1 (3.0) | 4.3 (3.1) | <.001 ‡ |

| Percent of rehabilition days agitated (mean, SD)|| | 8.9 (19.4) | 18.8 (25.2) | 15.9 (25.1) | 8.5 (17.8) | 4.1 (12.9) | 1.2 (7.2) | <.001 ‡ |

| Average of three highest ABS scores (mean, SD) | 21.8 (8.5) | 27 (9.8) | 25.6 (9.5) | 22.6 (7.8) | 19.2 (6.2) | 16.6 (4.0) | <.001 ‡ |

| Fall (%) | 6.5 | 11.8 | 9.4 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 3.2 | <.001 ‡ |

| Number of falls (mean, SD)¶ | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 0.147 † |

| Fall with injury (%) | 2.0 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.016 ‡ |

| Number of falls with injury (mean, SD)¶ | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 0.394 † |

NOTE: Abbreviations: CSI, Comprehensive Severity Index; PTA, Post traumatic amnesia; ABS, agitated behavior scale;

n=10 patients missing admission FIM cognitive score.

Analysis of variance test.

Chi-Square analysis.

Average of highest of 3 daily pain scores over rehabilitation stay.

Percent of rehabilition days agitated, starting with the beginning of the first bout to the end of the last bout, interruptions between bouts excluded.

Data include only patients who fell.

Outcome Variables

Three main outcome variables at discharge were: discharge FIM, length of stay (LOS) (which excludes days out of the rehabilitation facility for readmission to acute care), and discharge destination. We also examined readmission to acute care during rehabilitation as an outcome. In addition, outcomes collected post-discharge via telephone interview included hospitalizations post-discharge, employment, education, FIM, community participation (measured by the Participation Assessment with Recombined Tools Objective- PART-O, a 17-item objective tool representing functioning at the societal level),26 and subjective well-being (measured by Satisfaction with Life Scale- SWLS, a 5-item instrument used to measure life satisfaction).27 The summary score for the PART-O represents the average of item scores ranging from 0 to 5, while the SWLS Total score is a sum of the 5 items, ranging from 7–35. For both measures, higher scores represent better functioning or satisfaction. A summary of these data elements is provided in tables 5 and 6.

Table 5.

Rehabilitation Discharge Outcomes by Admission FIM Cognitive Score Subgroup

| Characteristics | Admission FIM Cognitive Score* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=2130) | <=6 (n=339) | 7–10 (n=374) | 11–15 (n=495) | 16–20 (n=408) | >=21 (n=504) | P | |

| LOS and discharge disposition | |||||||

| Rehabilitation LOS - excludes interruptions (mean, SD) | 26.5 (19.9) | 40.4 (27.6) | 32.5 (18.4) | 24.4 (15.4) | 21 (15.5) | 19 (15.1) | <.001 † |

| Discharge disposition (%) | <.001 ‡ | ||||||

| Private home | 83.9 | 73.7 | 78.1 | 85.7 | 85.0 | 92.3 | |

| Acute care hospital | 2.0 | 4.1 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.8 | |

| Other post acute setting | 14.0 | 22.1 | 19.3 | 13.7 | 12.3 | 6.9 | |

| Severity scores | |||||||

| Discharge brain injury component of CSI score (mean, SD) | 22.6 (15.3) | 34.3 (19.9) | 30.7 (15.8) | 22.9 (10.8) | 18.3 (8.8) | 11.5 (7.6) | <.001 † |

| Discharge non-brain injury component of CSI score (mean, SD) | 10.2 (11.1) | 10.9 (12.6) | 12.3 (11.5) | 10.8 (10.6) | 10 (11.5) | 7.4 (8.8) | <.001 † |

| Functional indepedence measures | |||||||

| Discharge FIM motor score - untransformed (mean, SD) | 63.0 (18.8) | 50.0 (21.1) | 56.8 (18.8) | 64.1 (16.2) | 66.9 (16.0) | 72.4 (14.8) | <.001 † |

| Discharge FIM motor score - Rasch transformed (mean, SD) | 55.7 (15.9) | 44.8 (17.5) | 50.7 (13.7) | 56 (12.6) | 58.7 (13.2) | 64.4 (15.4) | <.001 † |

| Discharge FIM cognitive score - untransformed (mean, SD) | 22.0 (6.6) | 15.9 (7.0) | 18.0 (5.3) | 21.2 (4.7) | 23.9 (4.0) | 28.4 (3.7) | <.001 † |

| Discharge FIM cognitive score - Rasch transformed (mean, SD) | 54.4 (15.1) | 40.2 (18.0) | 47 (10.6) | 53 (9.4) | 57.9 (8.5) | 68.3 (11.1) | <.001 † |

| Discharge FIM cognitive score (%) | <.001 ‡ | ||||||

| <=6 | 2.1 | 11.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| 7–10 | 3.9 | 15.3 | 7.5 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 11–15 | 9.8 | 20.7 | 24.6 | 8.1 | 1.2 | 0.2 | |

| 16–20 | 21.8 | 25.1 | 35.6 | 34.6 | 16.2 | 1.6 | |

| >=21 | 62.3 | 27.4 | 31.8 | 56.2 | 82.4 | 98.2 | |

NOTE: Abbreviations: CSI, Comprehensive Severity Index;

n=10 patients missing admission FIM cognitive score.

Analysis of variance test.

Chi-Square analysis.

Table 6.

None Month Post Discharge Outcomes by Admission Cognitive FIM Score Subgroup

| Characteristics | Admission FIM Cognitive Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=1850*) | <=6 (n=301) | 7–10 (n=331) | 11–15 (n=434) | 16–20 (n=353) | >=21 (n=424) | P | |

| Functional indepedence measures | |||||||

| 9-month post discharge FIM motor score - untransformed, n=1538 (mean, SD) | 82.6 (15.6) | 75.9 (22.0) | 80.6 (17.6) | 83.5 (15.0) | 84.9 (10.7) | 86.2 (10.1) | <.001 † |

| 9-month post discharge FIM motor score - Rasch transformed, n=1538 (mean, SD) | 80.8 (20.0) | 72.3 (25.1) | 77.9 (20.7) | 82.5 (19.1) | 83 (16.8) | 85.4 (16.4) | <.001 † |

| 9-month post discharge FIM cognitive score - untransformed, n=1560 (mean, SD) | 29.9 (5.7) | 27.1 (7.5) | 28.5 (6.4) | 30.3 (5.0) | 30.8 (4.7) | 31.8 (3.7) | <.001 † |

| 9-month post discharge FIM cognitive score - Rasch transformed, n=1560 (mean, SD) | 76.3 (18.0) | 68.1 (20.8) | 72.1 (18.8) | 76.9 (16.6) | 78.9 (16.3) | 82.2 (14.9) | <.001 † |

| 9-month post discharge FIM cognitive score subgroups, n=1560 (%) | <.001 ‡ | ||||||

| <=6 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 7–10 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 11–15 | 1.7 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.3 | |

| 16–20 | 5.5 | 11.3 | 10.4 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 1.1 | |

| >=21 | 91.5 | 78.6 | 85.7 | 93.7 | 96.3 | 98.6 | |

| Participation Assessment With Recombined Tools | |||||||

| PART score and subscores (mean, SD) | |||||||

| Total score, n=1665 | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.7) | <.001 † |

| Productivity score, n=1672 | 1.1 (1.0) | 0.7 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.0) | <.001 † |

| Social relations score, n=1666 | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.4 (0.9) | 0.007 † |

| Out and about score, n=1669 | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.7) | 0.034 † |

| Selected outcomes | |||||||

| Employed at 9-month interview (%) | 17.7 | 7.0 | 14.8 | 18.7 | 18.4 | 26.2 | <.001 ‡ |

| Pursuing education at 9-month interview (%) | 10.8 | 9.3 | 10.6 | 13.1 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 0.412 ‡ |

| Hospitalized overnight after rehabilitation discharge (%) | 27.5 | 30.6 | 29.6 | 28.1 | 26.4 | 23.8 | 0.253 ‡ |

| Seen in emergency department (%) | 28.8 | 29.9 | 32.6 | 28.1 | 30.0 | 25.0 | 0.208 ‡ |

| Overnight stay in a long term care facility (%) | 15.0 | 21.9 | 22.7 | 11.1 | 16.7 | 6.8 | <.001 ‡ |

| Days from rehabilitation discharge to 9-month interview, n=1683 (mean, SD) | 312.4 (46.0) | 300.6 (47.2) | 305.1 (44.8) | 311.2 (42.9) | 318.8 (47.7) | 323.0 (44.3) | <.001 † |

| Satisfaction with life scale | |||||||

| Satisfaction with life total score, n=1345 (mean, SD) | 21.7 (8.4) | 20.3 (8.6) | 21.8 (8.2) | 21.6 (8.4) | 21.8 (8.5) | 22.5 (8.3) | 0.093 † |

| Patient satifaction with life score >=21, n=1345 (%) | 56.9 | 52.5 | 57.3 | 56.4 | 56.3 | 59.7 | 0.654 † |

NOTE:

When sample size is indicated in a characteristic label, it represents that the sample size is smaller than 1850 because interviewees did not answer every question.

Analysis of variance test.

Chi-Square analysis.

Data Analyses

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). When data were missing, one or more adjustments were made depending on the variable and its intended use in analyses. Sometimes we categorized values simply as “unknown” (and included the category in analysis as a dummy variable representing missingness); sometimes we excluded patients with missing data from analysis; and sometimes we collapsed continuous variables with missing data into categorical variables and placed the cases with missing information into a category using corroborating data available. For example, we did not always have a patient’s Body Mass Index, but had other weight- and height-related information (e.g., an order for a bariatric wheelchair) that allowed categorizing a patient broadly, e.g., as overweight or obese.

Since we knew that our sample had patients with a wide range of functional disability, in the analysis our first step was to determine homogeneous subgroups of patients with TBI severity of brain injury. We tried different ways to create homogeneous subgroups and compared these ways based on how much variation in the outcomes was explained (R2 and c statistics) and how distinct the subgroups were. After exploring many possible approaches, including Case Mix Groups as defined for inpatient rehabilitation patients with TBI,28 time to clear PTA, and various combinations of admission FIM motor and cognitive scores, we determined that the admission FIM cognitive score was the best way to form relatively homogenous subgroups of TBI patients and defined five subgroups (score ≤6, 7–10, 11–15, 16–20, ≥21).

We used frequencies and percentages for categorical patient, treatment, rehabilitation course, and outcome measures, and means, medians, and amount of variation (SD and range) to summarize continuous measures. We conducted bivariate analyses to examine how different the patients were across the 5 FIM cognitive subgroups. For categorical variables, we created contingency tables and used chi-squared tests to determine significance of bivariate associations. For continuous variables we used analysis of variance. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In order to examine how the TBI-PBE study patients compare to patients with TBI who received inpatient rehabilitation in the US during specific years, we used two sources of data regarding the total US TBI inpatient rehabilitation population (i.e., 99,438 for 2001–2007, and 156,447 for 2001–2010). Two papers provided most variables of interest (e.g. age group, LOS category, etc.) in percentages, which were converted to raw numbers by multiplying each with their respective US TBI population totals.29,30 The 2001–2007 values were subtracted from the 2001–2010 values to get the 2008–2010 values. These raw numbers were then converted back into percentages using 156,447 − 99,438 = 57,009 as the denominator (our estimate for the US TBI population between 2008 and 2010). As done with previous comparisons to national data, differences less than 5% were considered immaterial; those ≥ 5% but < 10% were considered minor; and those ≥ 10% were considered important.26 Only US TBI-PBE patients were included in the comparison.

RESULTS

The average age of the 2130 patients was 44.5 (SD=21.3), with 72.5% male and 74.4% white non-Hispanic, 15.1% black, 6.2% white Hispanic, and 4.4% in the Miscellaneous race/ethnicity group. In table 2 we show the patient pre-injury and injury characteristics overall and within each admission cognitive subgroup. The less impaired cognitive subgroups (score ≥16) generally were older and contained more retired people; had a greater percentage females; were better educated; had Medicare more often as payer and Medicaid less often; and were heavier (higher BMI). These groups had a lower percentage of patients with paralysis or diabetes; a lower admission CSI; and a higher percentage with injury due to falling with more mild impairment (GCS 13–15) immediately after injury. Higher cognitive subgroups also had the following: less frequently midline shift present; fewer subarachnoid or intraventricular hemorrhages; fewer craniectomies performed; and less time from injury to rehabilitation admission. These patients also had less functional impairment as measured by FIM motor score.

The admission FIM cognitive subgroups had different percentages of patients receiving various medications, nutritional supports, and other treatments. The lowest admission cognitive subgroups (score ≤ 10) had a greater percentage of patients being physically restrained and getting one-on-one observers during rehabilitation; more often had enteral and parental nutrition; more often had a tracheotomy; and received more psychoactive and other medication use.

The lower cognitive functioning subgroups also differed in percentage of patients receiving various therapy activities, as well as in amount of treatment (cumulatively over their stay) by each discipline for those patients receiving each activity. Treatment time differences were closely associated with LOS differences. Examples of these data are presented in table 3. The low functioning groups had fewer minutes/week of PT therapeutic exercise and more minutes/week gait training and standing. In OT, these subgroups had fewer minutes/week in upper extremity activity and lower body dressing and more minutes/week in cognitive activity. For SLP, lower functioning cognitive patients had fewer minutes/week of education and verbal reasoning, along with more minutes/week of verbal orientation review. In psychology, in general the highest percent of patients receiving each activity and for more minutes/week was the middle functioning cognitive subgroup (score 11–15); subgroups functioning at a lower level on admission tended to receive fewer minutes/week of psychology activities. Recreational therapy also tended to be given more frequently to patients in the middle cognitive functioning subgroup, but more minutes/week of most activities were given to patients in the higher functioning admission cognitive subgroups. A higher percent of patients in the lowest admission cognitive subgroup received social work/case management activities.

Whereas table 2 provides patient pre-injury and injury characteristics, table 4 offers information on events and experiences during the rehabilitation stay. As expected, patients in the lower admission cognitive functioning subgroups had moderate to severe aphasia, dysphagia, and ataxia more often, longer time in PTA, and a greater percentage of their stay characterized by an agitated state.

Outcomes at discharge and at approximately 3- and 9-months post-discharge (approximately 1-year post-injury for most) are presented in tables 5 and 6, respectively. Table 7 provides key information on the original sample of 2130 (last column), and the samples that we classified as having a 3-month post-discharge and a 9-month post discharge follow-up interview, as well as for ANY follow-up. For the 3-month interviews, the average time from discharge to the interview was 98.5 days (SD=28.0. range 56 – 189 days); for the 9-month interviews, the average time from discharge to the interview was 309.3 days (SD=43.3. range 208 – 402 days). In Table 7 we also included a description of patients who had a 1-year post-injury interview. Because the 1-year post-injury anniversary date could fall in the window for any post-discharge interview, depending on the patient’s length of stay in acute and rehabilitation settings, additional questions required for the 1-year post-injury interview for TBI Model Systems database participants were included in the follow-up interview that fell within the window for 3- or 9-month post-discharge interview. The outcomes generally show an association with the severity of the cognitive impairment at admission, with less impaired patients showing shorter LOS, more discharges to home, higher levels of functioning (FIM) at discharge, 3, and 9 months, fewer post-discharge hospitalizations, and fewer deaths post discharge.

Table 7.

Follow-up Interview Rates and Subpopulation Comparison

| Time of interview | 3-month post-discharge | 9-month post-discharge | 1-year post-injury* | Any follow-up data† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interview conducted | 1742 | 1649 | 1605 | 1850 |

| Deceased or incarcerated | 40 | 92 | 69 | 92 |

| Lost to follow-up | 199 | 240 | 307 | 39 |

| Ineligible for follow-up | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 |

| % with interview conducted | 81.8% | 77.4% | 75.4% | 86.9% |

| % with known outcome‡ | 83.7% | 81.7% | 78.6% | 91.2% |

| Characteristic | 3-month post-discharge (n=1742) | 9-month post-discharge (n=1649) | 1-year post-injury (n=1605) | Any follow-up data (n=1850) | Full Sample (n=2130§) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at rehabilitation admission (mean, SD) | 43.7 (20.8) | 43.3 (20.9) | 43.3 (20.9) | 43.8 (20.9) | 44.5 (21.3) |

| Male (%) | 72.7 | 71.9 | 71.6 | 72.4 | 72.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||||

| Black | 14.5 | 13.9 | 13.8 | 14.6 | 15.1 |

| White | 77.0 | 77.2 | 77.8 | 76.1 | 74.4 |

| White Hispanic | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 6.2 |

| Other and unknown | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 4.4 |

| Highest education achieved (%) | |||||

| Some high school, no diploma | 23.4 | 23.3 | 23.1 | 23.7 | 23.0 |

| High school diploma | 25.9 | 26.0 | 26.1 | 26.2 | 25.9 |

| Work towards or completed | 17.2 | 18.8 | 18.6 | 17.7 | 16.2 |

| Associate’s degree | |||||

| Work towards or completed | 20.2 | 20.4 | 20.7 | 19.9 | 19.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree | |||||

| Work towards or completed | 10.2 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 9.7 |

| Master’s/Doctoral degree | |||||

| Unknown | 3.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 5.7 |

| Primary payer for inpatient stay (%) | |||||

| Medicare | 18.7 | 18.0 | 18.3 | 18.9 | 19.4 |

| Medicaid | 16.7 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 16.4 | 15.5 |

| Private insurance | 25.1 | 25.1 | 25.2 | 24.6 | 24.5 |

| Centralized (single payer system) | 6.2 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 6.9 |

| Worker’s compensation | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.8 |

| Self pay/None | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.6 |

| MCO/HMO | 15.4 | 16.1 | 16.2 | 15.2 | 14.4 |

| No-fault auto insurance | 4.1 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.5 |

| Other/unknown | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| Marital status at injury (%) | |||||

| Single/never married | 43.7 | 44.0 | 44.2 | 43.1 | 42.6 |

| Married/common law | 35.8 | 35.9 | 35.8 | 36.3 | 36.5 |

| Previously married | 17.0 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 17.1 | 17.5 |

| Other/unknown | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Employment prior to injury (%) | |||||

| Employed and student | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.0 |

| Employed only | 46.8 | 47.7 | 47.3 | 47.0 | 47.1 |

| Unemployed | 14.4 | 13.8 | 14.1 | 14.2 | 13.3 |

| Retired | 21.9 | 21.3 | 21.5 | 22.3 | 23.1 |

| Student only | 11.8 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 11.4 | 11.4 |

| Unknown | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Brain injury component of admission CSI score (mean, SD) | 45.7 (23.8) | 46 (23.7) | 45.7 (23.6) | 45.5 (23.7) | 44.7 (23.7) |

| Non-brain injury component of admission CSI score (mean, SD) | 17.1 (15.1) | 17.2 (14.9) | 17.1 (15.1) | 17.0 (15.1) | 16.9 (15.0) |

| Admission FIM cognitive score - untransformed (mean, SD) | 14.6 (7.2) | 14.6 (7.1) | 14.7 (7.2) | 14.7 (7.2) | 14.8 (7.2) |

| Admission FIM motor score - untransformed (mean, SD) | 34.0 (19.4) | 33.9 (19.5) | 34.2 (19.5) | 34.3 (19.5) | 34.7(19.7) |

NOTE: Abbreviations: MCO/HMO, Managed care organization/Health maintainance organization; CSI, Comprehensive Severity Index;

Because the anniversary date for a person’s injury could fall in the window for any post-discharge interview (3 month had a window from 56 to 189 days post-discharge; 9-month had a window from 208 to 402 days post-discharge), the additional questions required were included in the follow-up interview that fell within the window of a post-discharge interview.

At the commencement of the study there were also 6-month post-discharge interviews, however this facet of the study was discontinued due to feasibility issues.

Includes interviewed patients and those who were deceased or incarcerated at the indicated interview time.

n=10 patients missing admission FIM cognitive score.

In table 8 we compare the TBI-PBE US study patients to the US inpatient rehabilitation population. With such large numbers for the US TBI patients, all differences are statistically significant (p<.001). The TBI-PBE patients tend to be younger, and hence are less often covered by Medicare and more often by Medicaid and private payers. TBI-PBE patients are more severely injured, with a higher percentage with an admission motor FIM ≤ 23 and admission cognitive FIM ≤ 15; there also is a greater percentage of patients in the most severe TBI Case Mix Group (207) and with a rehabilitation LOS of over 20 days. However, after we separated the TBI-PBE sample by age at < and ≥ 65 years, the vast majority of differences became immaterial or minor (<10%).

Table 8.

TBI-PBE sample and US TBI rehabilitation population: key demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | All ages | Age less than 65 | Age 65+ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBI-PBE US only (n=1981) | US National TBI* (n~†57009) | Difference: | TBI-PBE US only (n=1562) | US National TBI (n~27146) | Difference: | TBI-PBE US only (n=419) | US National TBI (n~29863) | Difference: | |

| Age at rehabilitation admission (%) | |||||||||

| <16 | 0.7 | 0.0 | −0.7 | 0.9 | 0.0 | −0.9 | NA | NA | NA |

| 16–19 | 10.2 | 4.4 | −5.8 | 13.0 | 9.3 | −3.7 | NA | NA | NA |

| 20–29 | 24.4 | 9.9 | −14.5 | 31.0 | 21.3 | −9.7 | NA | NA | NA |

| 30–39 | 12.6 | 6.4 | −6.2 | 15.9 | 14.1 | −1.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| 40–49 | 14.0 | 9.0 | −5.0 | 17.7 | 19.5 | 1.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| 50–59 | 11.7 | 11.0 | −0.7 | 14.9 | 23.4 | 8.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| 60–69 | 9.8 | 12.9 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 12.2 | 5.6 | 22.0 | 13.4 | −8.6 |

| 70–79 | 8.6 | 19.7 | 11.1 | NA | NA | NA | 40.8 | 36.3 | −4.5 |

| 80–89 | 6.9 | 22.5 | 15.6 | NA | NA | NA | 32.5 | 42.4 | 9.9 |

| 90–99 | 1.0 | 4.2 | 3.2 | NA | NA | NA | 4.5 | 7.9 | 3.4 |

| 100 and older | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | NA | NA | NA | 0.2 | 0.0 | −0.2 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | 0.0 | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Gender (%) | |||||||||

| Male | 72.5 | 62.7 | −9.8 | 76.2 | 73.9 | −2.3 | 58.7 | 52.4 | −6.3 |

| Female | 27.5 | 37.4 | 9.9 | 23.8 | 25.8 | 2.0 | 41.3 | 47.6 | 6.3 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |||||||||

| White | 74.7 | 77.2 | 2.5 | 73.0 | 70.5 | −2.5 | 80.7 | 83.2 | 2.5 |

| African-American | 15.8 | 8.4 | −7.4 | 16.8 | 11.9 | −4.9 | 11.9 | 5.1 | −6.8 |

| Hispanic | 6.6 | 7.4 | 0.8 | 7.1 | 9.7 | 2.6 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 0.4 |

| Other | 2.8 | 5.6 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 5.8 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 4.9 | 2.3 |

| Missing | 0.1 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Primary payer (%) | |||||||||

| Private | 46.6 | 29.6 | −17.0 | 56.6 | 54.3 | −2.3 | 9.3 | 7.8 | −1.5 |

| Medicare | 20.9 | 53.6 | 32.7 | 4.4 | 11.9 | 7.5 | 82.6 | 90.5 | 7.9 |

| Medicaid | 16.7 | 6.7 | −10.0 | 20.2 | 13.9 | −6.3 | 3.6 | 0.5 | −3.1 |

| Workers’ Compensation | 7.3 | 2.8 | −4.5 | 8.4 | 4.7 | −3.7 | 3.1 | 0.7 | −2.4 |

| Self-pay or no pay | 4.9 | 4.8 | −0.1 | 6.0 | 10.2 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | −0.8 |

| Other | 3.4 | 2.5 | −0.9 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | −0.1 |

| Missing | 0.3 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| FIM motor score at admission (%) | |||||||||

| 13 | 16.0 | 5.8 | −10.2 | 17.1 | 7.6 | −9.5 | 11.9 | 4.4 | −7.5 |

| 14–23 | 24.4 | 18.3 | −6.1 | 23.7 | 18.4 | −5.3 | 27.0 | 18.3 | −8.7 |

| 24–33 | 17.1 | 18.5 | 1.4 | 15.9 | 14.1 | −1.8 | 21.5 | 22.4 | 0.9 |

| 34–43 | 15.5 | 21.0 | 5.5 | 13.9 | 16.9 | 3.0 | 21.5 | 24.7 | 3.2 |

| 44–53 | 12.8 | 21.3 | 8.5 | 13.3 | 20.9 | 7.6 | 11.0 | 21.4 | 10.4 |

| 54–63 | 9.1 | 11.5 | 2.4 | 10.1 | 15.6 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 7.7 | 2.2 |

| 64–73 | 3.3 | 2.9 | −0.4 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | −0.7 |

| 74–83 | 1.0 | 0.5 | −0.5 | 1.2 | 0.9 | −0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| 84–91 | 0.3 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Missing | 0.5 | 0.0 | −0.5 | 0.6 | 0.0 | −0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| FIM cognitive score at admission (%) | |||||||||

| 5 | 12.7 | 8.9 | −3.8 | 12.4 | 12.5 | 0.1 | 14.1 | 5.9 | −8.2 |

| 6–15 | 47.2 | 34.9 | −12.3 | 49.9 | 39.2 | −10.7 | 37.2 | 31.2 | −6.0 |

| 16–25 | 32.6 | 40.4 | 7.8 | 31.1 | 35.5 | 4.4 | 37.9 | 44.3 | 6.4 |

| 26–35 | 7.0 | 15.8 | 8.8 | 6.0 | 12.8 | 6.8 | 10.7 | 18.6 | 7.9 |

| Missing | 0.5 | 0.0 | −0.5 | 0.6 | 0.0 | −0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Case-mix groups‡ (%) | |||||||||

| 201 MotorWt§>53.36, Cog>23.5 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.1 | −0.6 |

| 202 44.25<MotorWt<53.35, Cog>23.5 | 1.8 | 5.0 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 4.9 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 4.8 | 2.9 |

| 203 MotorWt>44.25, Cog<23.5 | 13.8 | 10.7 | −3.1 | 15.7 | 16.9 | 1.2 | 6.7 | 4.9 | −1.8 |

| 204 40.65<MotorWt<44.25 | 4.3 | 8.1 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 8.5 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 7.9 | 3.8 |

| 205 28.75<MotorWt<40.65 | 20.3 | 28.4 | 8.1 | 19.0 | 23.5 | 4.5 | 25.3 | 32.6 | 7.3 |

| 206 22.05<MotorWt<28.75 | 13.2 | 14.6 | 1.4 | 12.4 | 11.5 | −0.9 | 16.2 | 17.7 | 1.5 |

| 207 MotorWt<22.05 | 43.8 | 30.7 | −13.1 | 43.7 | 30.9 | −12.8 | 44.2 | 31.1 | −13.1 |

| Missing | 0.5 | −0.1 | −0.6 | 0.6 | −5.2 | −5.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

N~57009 (2008–2010) based on US National TBI n=156447 (2001–2010) minus US National TBI n=99438 (2001–2007). Slight overlap TBI-PBE and 2009/2010 US TBI samples. TBI-PBE includes US facilities only.

approximately.

Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services case mix groups for payment of patients with TBI in rehabilitation centers.

Weighted FIM motor score from CMG definitions.

DISCUSSION

There is a significant need for evidence in TBI rehabilitation that delineates the extent that differences in outcomes are attributable to patients’ characteristics such as age, severity, time since injury, and pre-injury factors, and how much outcomes can be attributed to the timing and dose of specific rehabilitation interventions. Our large sample, 10-center, comparative effectiveness study using the PBE methodology provides information on a comprehensive set of patient prognostic factors; information on the types, intensity, and duration of key activities used in interdisciplinary rehabilitation using a separate taxonomy for each discipline; and outcomes at inpatient rehabilitation discharge and 3 and 9 months later.

Our sample of 2,130 was diverse with regard to demographics, injury (etiology, physiologic damage, and severity), and functioning (FIM Cognitive and Motor scores) at inpatient rehabilitation admission. Sample stratification into 5 levels of functional capacity based on admission FIM Cognitive scores resulted in sufficiently large subsamples (N range 339 to 504) for between group analyses. Strong evidence of differentiation between the 5 cognitive groups was observed with regard to acute brain injury severity (GCS scores), brain damage (midline shift and subarachnoid hemorrhage), nature of the acute care received (craniectomy, tracheotomy or ventilation, and length of stay), inpatient rehabilitation admission brain injury severity (CSI Brain Injury scores and presence of severe dysphagia, aphasia, and ataxia), and inpatient rehabilitation admission motor functioning.

Our POC forms developed as part of this study allowed clinicians to document a wide range of therapeutic activities potentially used within each discipline including PT (19 separate activities), OT (36), SLP (86), TR (43), PSY (8), and Social Work (6). ). In each discipline, significant heterogeneity in treatment activities delivered was observed within and between groups. For example, gait training was the most frequently delivered PT activity (about 80 minutes per week) across all subgroups but the consistently large SDs indicate that the average minutes per week of gait training ranged from 0 minutes to well over 3 hours within each group (table 3). Within and across subgroups, there is variation in whether or not patients get a particular treatment (%), and the average minutes they get per week. Across disciplines, persons in the highest functioning cognitive group participated in the most minutes of formal assessment/testing per week, likely reflecting a combination of short stays and greater ability to complete test requirements, resulting in less overall time in other activities.

Inpatient rehabilitation outcomes showed trends in the expected direction across the 5 admission cognitive categories. Patients admitted with more severe cognitive impairments had lower inpatient rehabilitation discharge cognitive and motor functional outcomes, higher inpatient rehabilitation discharge brain injury CSI scores, longer inpatient rehabilitation stay, and were more likely to be discharged to an institutional setting. Nine-month post discharge outcome data suggest that all patient subgroups had improved cognitive and motor functioning (table 6).

The quality of evidence to be derived from our prospective, multi-center, longitudinal study rests on standardized data collection tools, completeness of data collection, and very low attrition rates after inpatient rehabilitation discharge. The follow-up rate (79%) for one-year post-injury outcomes approached the benchmark of 80% for follow-up completeness. Examination of interactions and potential confounds as alternative explanations for the differences in outcomes between the 5 admission cognitive subgroups as well as evaluation of the effects of treatments on outcomes was beyond the scope of this introductory paper. Future analyses, including studies published in this supplement, will explore confounds when evaluating: (1) what percent of variation in treatment is accounted for by variation in patient characteristics, (2) what percent of variation in outcomes is accounted for by variation in treatment after controlling for patient and injury characteristics, and (3) what treatments and treatment patterns are most strongly related to positive outcomes for specific subgroups of patients.

Evidence from this study has important implications for future research as well as for the way that injury is categorized for persons with TBI receiving inpatient rehabilitation. The demographic, injury severity, and functional diversity of this large, multi-center sample along with the heterogeneity of both treatments delivered and outcomes observed within each of the cognitive subgroups increases the likelihood that statistical modeling will identify treatments that are associated with outcomes of interest. Preliminary evidence suggests that categorization of patients with TBI based on functional cognition at inpatient rehabilitation admission produces associations with injury characteristics, inpatient rehabilitation admission level of motor functioning and secondary conditions, rehabilitation discharge outcomes, and one-year post-injury outcomes. Historically, case-mix stratification in rehabilitation, e.g., Case Mix Groups 201–207, has focused on the physical dimension of functioning, differentiating 7 levels of FIM motor functioning within TBI admissions. Cognitive functioning (dichotomized as FIM Cognitive scores < or ≥23.5 is used only to differentiate among patients with a (weighted) Motor score of more than 44.25. Yet, our preliminary data show that cognition- and behavior-focused activities are common if not predominant in SLP, OT, and psychology interventions and that the current Case Mix Groups may undervalue the cognitive dimension. Our preliminary analysis indicates that additional levels of stratification by cognitive functioning in the TBI rehabilitation population yield important prognostic information. Further evidence that patients in specific cognitive subgroups substantially benefit from additional rehabilitation treatment not factored into current case-mix groups may argue for case-mix reform with more emphasis placed on the cognitive dimension in inpatient rehabilitation treatment.

Findings from the TBI-PBE study are likely to generalize to the US rehabilitation population of persons with TBI. A comparison of our sample to a concurrent group of U.S. patients, when dichotomized at age 65, indicated that persons in our sample were similar to persons in their respective age groups in the wider US TBI rehabilitation population.

CONCLUSIONS

This prospective, 10-center, comparative effectiveness study using the PBE methodology succeeded in developing a standardized treatment taxonomy and prospectively capturing naturally occurring variation within patients and treatments. This preliminary information offers a basis for subsequent papers from this study to investigate best treatments for specific patient impairments and groups.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Funding for this study came from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (grant 1R01HD050439-01), the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (grant H133A080023), and the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation (grant 2007-ABI-ISIS-525).

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of clinical and research staff at each of the 10 inpatient rehabilitation facilities represented in the study. The study center directors included: John D. Corrigan, PhD and Jennifer Bogner, PhD (Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH); Nora Cullen, MD (Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, Toronto, ON Canada); Cynthia L. Beaulieu, PhD (Brooks Rehabilitation Hospital, Jacksonville, FL); Flora M. Hammond, MD (Carolinas Rehabilitation, Charlotte, NC [now at Indiana University]); David K. Ryser, MD (Neuro Specialty Rehabilitation Unit, Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, UT); Murray E. Brandstater, MD (Loma Linda University Medical Center, Loma Linda, CA); Marcel P. Dijkers, PhD (Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY); William Garmoe, PhD (Medstar National Rehabilitation Hospital, Washington, DC); James A. Young, MD (Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL); Ronald T. Seel, PhD (Crawford Research Institute, Shepherd Center, Atlanta, GA). We also acknowledge the contributions of Michael Watkiss in data collector training and support during data collection.

Abbreviations

- ADM

Auxiliary Data Module

- CSI

Comprehensive Severity Index

- FIM

Functional Independence Measure

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Scale

- LOS

Length of stay

- OT

Occupational therapy

- PBE

Practice-Based Evidence

- POC

Point of care documentation forms

- PT

Physical therapy

- PTA

Post traumatic amnesia

- SLP

Speech Language Pathology

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

Appendix 1

TBI-PBE Physical Therapy Form v.3.19.09

TBI-PBE Occupational Therapy Form v.11.19.08

TBI-PBE Speech and Language Pathology Form v. 1.15.09

TBI-PBE Therapeutic Recreation Form v.10.6.08