Abstract

Our objective was to evaluate the progression and regression of cervical dysplasia in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive women during the late antiretroviral era. Risk factors as well as outcomes after treatment of cancerous or precancerous lesions were examined. This is a longitudinal retrospective review of cervical Pap tests performed on HIV-infected women with an intact cervix between 2004 and 2011. Subjects needed over two Pap tests for at least 2 years of follow-up. Progression was defined as those who developed a squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL), atypical glandular cells (AGC), had low-grade SIL (LSIL) followed by atypical squamous cells-cannot exclude high-grade SIL (ASC-H) or high-grade SIL (HSIL), or cancer. Regression was defined as an initial SIL with two or more subsequent normal Pap tests. Persistence was defined as having an SIL without progression or regression. High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) testing started in 2006 on atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) Pap tests. AGC at enrollment were excluded from progression analysis. Of 1,445 screened, 383 patients had over two Pap tests for a 2-year period. Of those, 309 had an intact cervix. The median age was 40 years and CD4+ cell count was 277 cells/mL. Four had AGC at enrollment. A quarter had persistently normal Pap tests, 64 (31%) regressed, and 50 (24%) progressed. Four developed cancer. The only risk factor associated with progression was CD4 count. In those with treated lesions, 24 (59%) had negative Pap tests at the end of follow-up. More studies are needed to evaluate follow-up strategies of LSIL patients, potentially combined with HPV testing. Guidelines for HIV-seropositive women who are in care, have improved CD4, and have persistently negative Pap tests could likely lengthen the follow-up interval.

Introduction

It is well established that women with HIV have higher rates of atypical Pap tests,1–3 higher rates of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection,4 faster progression of cervical dysplasia,5–7 and higher rates of cervical cancer.8,9 A recent systematic global review10 looking at the incidence and progression of cervical lesions in women with HIV showed that HIV-infected women had a median 3-fold higher incidence of cervical lesions compared to HIV-negative women. It also reported that HIV-positive women were at least twice as likely to have cervical lesions that progressed in severity to HIV-negative women, although this did not reach statistical significance due to sample size. This increased risk for cervical cancer has led to increased follow-up and closer screening recommendations.11,12 Most of these data came before antiretroviral medications were consistently in use4,13 and data in the combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) era are just emerging,14 particularly around progression and regression.15

The natural history of HPV infection and squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) in the cART era is not yet fully understood. With strong local and systemic T cell-mediated immune response to HPV, HPV replication could be expected to decrease locally and SIL to regress, resulting in a decreased incidence of anogenital cancers (AG).16–18 However, if cART does not result in enhanced control of HPV despite an increase in CD4 count and restoration of immunity to several opportunistic pathogens, then progression of HPV disease and an increased incidence of AG cancer would be expected. To date, lack of clearance of cervical HPV infection has been reported with cART.19 However, there are discrepant results on the association of cART and regression or progression of SIL.20

Our goal was to study the progression and regression of cervical dysplasia in HIV-positive women enrolled in care at an inner-city clinic in the United States during the late antiretroviral era. The role of high-risk HPV, sexually transmitted infections (STI), cigarette smoking, parity, CD4, and antiretroviral medication in the progression of cervical dysplasia was also examined. In addition, the outcomes after treatment of cancerous or precancerous lesions will be discussed.

Materials and Methods

Study population and study plan

This is a longitudinal retrospective review of cervical Pap tests performed on HIV-infected women with an intact cervix (i.e., without prior cervical surgery or excisional procedure) who were seen at the Infectious Diseases Program Ponce de Leon Center (IDP) of the Grady Health System between June 2004 and December 2011. Subjects had at least two documented cervical cytology tests over at least 2 years of follow-up. The IDP is a Ryan White funded outpatient clinic that provides care for more than 5,000 HIV-infected individuals annually, the majority with advanced AIDS.

Subjects were identified from a list of all cervical Pap tests performed from June 2004 to September 2010 at the IDP. For all patients, sociodemographic data and risk factors for HIV infection were collected; in addition, gynecologic and obstetric histories, CD4 cell counts, HIV viral load, and status of antiretroviral therapy were recorded. cART was defined as any combination therapy that included two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) combined with a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) or one or more protease inhibitor (PI). Cervical SILs were monitored according to protocols as follows: colposcopy-directed examination and biopsy for atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) HPV unknown or positive for high-risk HPV, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), and conization or loop electrosurgical excision (LEEP) for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) of grade II or greater.

Pap test collection

All cervical Pap tests were performed using liquid-based cytology. All Pap tests were reviewed initially by a cytotechnologist. Pap tests assessed as abnormal by the cytotechnologist were then reevaluated by a cytopathologist. Pap test results were classified using the Bethesda classification according to the 2001 consensus guidelines with the following categories: negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM) and those with epithelial abnormalities: ASCUS, atypical squamous cells–cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H), LSIL, HSIL, and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).21

Reflex testing for ASCUS Pap tests for high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) was introduced in January 2006, using the Digene (Qiagen) HC2 HPV DNA Test. Patients with cervical Pap test results showing ASCUS-positive hrHPV, LSIL, or HSIL were routinely referred for colposcopy.

Definition of progression and regression of cervical Pap tests

Pap test progression was based on cytology results and includes patients who had NILM or ASCUS followed by LSIL, ASC-H, or HSIL or those who had LSIL followed by ASC-H or HSIL or those who developed cancer in follow-up. Normal to ASCUS was not considered progression. Pap test regression was defined as an initial SIL (HSIL or LSIL) on cervical cytology followed by at least two subsequent normal cervical cytologies (NILM or ASCUS-negative hrHPV). Persistence is defined as having a Pap test showing SIL with no evidence of progression or regression. Patients with atypical glandular cells (AGC) at any time are not included in the progression analysis.22

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were compared using Fischer's exact test and continuous variables using paired sample two-sided t tests as appropriate using SAS statistical software, release 9.3 (SAS Institute). A p value<0.05 was considered significant.

Institutional approval

This work was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board and the Grady Research oversight committee.

Results

Out of 1,445 patients who underwent cervical cytology screening at IDP between June 2004 and September 2010, 383 patients had at least two Pap tests over a 2-year period. Among those, 309 had an intact cervix at enrollment. Demographic information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Data on Patients with HIV, Followed with Pap Tests and Have an Intact Cervix

| Number of patients with data | Demographic data | Mean (standard deviation) | Median (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 309 | Age at enrollment | 39.9 (9.5) | 40 (19–67) |

| 299 | CD4 cell count at enrollment | 322 (254) | 277 (1–1,146) |

| 305 | Average CD4 | 397 (235) | 364 (27–1,123) |

| 309 | Undetectable viral load during study (%) | 67% (31) | 75% (0–100) |

| 309 | Duration of follow-up in months | 58 (16) | 60 (24–94) |

| 309 | Years from HIV diagnosis to enrollment | 7 (5) | 6 (0–24) |

| 309 | Gravida at enrollment | 3 (2) | 3 (0–11) |

| 289 | Smoking status | 113 (39%) | |

| 302 | RPR status | 7 (2%) | |

| 306 | Gonorrhea/chlamydia | 5 (2%) | |

| 307 | Bacterial vaginosis | 136 (44%) | |

| 307 | Trichomonas | 58 (19%) | |

| 303 | Hepatitis C AB+ | 38 (13%) | |

| 300 | Hepatitis B Ag+ | 14 (5%) | |

| 299 | Detectable viral load at enrollment | 138 (47%) | |

| 299 | Antiretroviral use at enrollment | 209 (70%) | |

| 307 | Race - African American 288 (93%), White 6 (2%), Other 13 (4%) | ||

RPR, rapid plasma reagin.

The majority of the subjects in this study were African American (93%). Of these, 39% reported a smoking history, 13% had positive hepatitis C antibody, and 5% had positive hepatitis B surface antigen. Two percent had a positive RPR, 45% had bacterial vaginosis, and 19% had Trichomonas. The women had been pregnant on average three times prior to enrollment. Of the 309 patients 68% were on antiretroviral therapy at least intermittently during the study period and the median CD4 count at the start of the study period was 277. Half of the cohort had at least 5 years of follow-up. There was also a strong association between CD4 <200 cells/ml at entrance pap smear and initial pap smear being an SIL (OR=2.41, 95% CI=1.71–3.40).

Nearly half of the initial Pap tests (139 out of 309) were negative (NILM) at the beginning of the study as can be seen in Table 2. Of those, 71 (51%) Pap tests remained persistently negative. The remaining 68 (49%) patients developed ASCUS, ASC-H, LSIL, AGC, or HSIL (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Longitudinal Follow-up of Initial Pap Tests

| Initial Pap | Total | Negative | Regress | Persist | Progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NILM | 138 | 71 (51%) | 40 (29%) | ||

| ASCUS-negative HPV | 10 | 6 (60%) | |||

| ASCUS high-risk HPV | 14 | 10 (71%) 2 progressed to cancer | |||

| ASCUS unknown HPV | 50 | 23 (46%) | |||

| LSIL | 74 | 28 (38%) | 34 (46%) | 8 (11%) 1 progressed to cancer | |

| ASC-H | 8 | 4 (50%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (13%) | |

| HSIL | 10 | 5 (50%) | 5 (50%) | ||

| SCC | 1 |

Atypical glandular cells (ACG) on initial Pap test were excluded from longitudinal follow-up.

NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy; ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells–cannot exclude HSIL; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

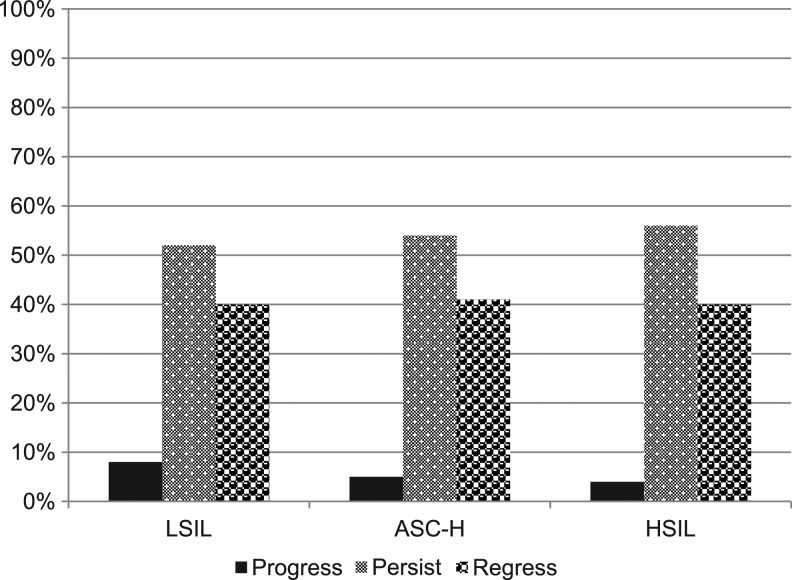

FIG. 1.

Evolution of all prevalent and incident squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) during follow-up (of those with follow-up data).

Of the 74 with initial Pap tests with ASCUS, 14 were positive for high-risk HPV, 10 were negative for high-risk HPV, and 50 did not have hrHPV reflex testing done. Of those, 17 progressed to LSIL, 12 to ASC-H or HSIL, and one to cancer.

Follow-up data from SILs are seen in Fig. 1. LSILs were detected in 74 subjects at study initiation. Of those 28 regressed, 34 persisted, and eight progressed, one to cancer. ASC-H was detected in eight women at the start of the study. Of those four regressed, two persisted, and one progressed. HSIL was detected in 10 patients at initiation; half regressed and half persisted. There were three who developed cancer and one who had cancer diagnosed with the initial Pap tests. The four patients who initially had AGC were not included in the longitudinal follow-up.

Evolution of all prevalent and incident SIL

We assessed the evolution of the cervical cytology among those with prevalent and incident SIL during the study period. As seen in Table 3, progression occurred in 8% of those with LSIL, 5% of ASC-H, and 4% of HSIL. Overall, 40% of all SIL regressed back to negative, 40% of LSIL, 41% of ASC-H, and 40% of HSIL without a surgical intervention. Persistence was observed in half of the SIL: 52% of LSIL, 54% of ASC-H, and 56% of HSIL.

Table 3.

Evolution of All Prevalent and Incident Squamous Epithelial Lesions During the Follow-up Period

| SIL | Total | Follow-up | Progress | Persist | Regress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSIL | 150 | 137 (91%) | 11 (8%)a | 71 (52%) | 55 (40%) |

| ASC-H | 51 | 37 (72%) | 2 (5%) | 20 (54%) | 15 (41%) |

| HSIL | 28 | 25 (89%) | 1 (4%) | 14 (56%) | 10 (40%) |

Out of those with follow-up data.

Prevalent and incident AGC

Of the 309, 22 had AGC during the study interval: four prevalent and 19 incident AGC. Eight AGC (62%) were positive for hrHPV among the 13 who were tested. This was similar to the rate for ASCUS where 93 (54%) were positive out of 172 tested.

Half of the AGC either progressed to SIL or underwent LEEP: two had ASC-H on follow-up and eight had LSIL. One underwent LEEP after she had three Pap tests showing AGC and the pathology was CIN1. Fifteen of 22 (68%) had colposcopy: four showed CIN1 and 11 had a negative biopsy. Seven did not have colposcopy: three had subsequent Pap tests with NILM, two with ASCUS, one with LSIL, and one with HSIL.

Factors based on progression

In a model controlling for 75 percent of undetectable viral load during follow up, average CD4+ cell count above 200 cells/mL, initial CD4+ count above 200 cells/mL, age above 40 years old, and initial Pap test category, only initial CD4+ count above 200 cells/mL was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of subsequent Pap tests regressing or remaining normal.

Colposcopy and intervention analysis

We compared the colposcopy results and the subsequent pathology seen on surgical resection, reported in Table 4. Of the 309 patients in the study, colposcopy and/or LEEP were performed on 171 (55%) of the cohort. Among those who underwent LEEP, 108 had high-risk HPV testing and 70 (65%) had high-risk HPV. There were 41 individuals who had an intervention (LEEP, cone, hysterectomy). Their initial Pap test consisted of four NILM, two ASCUS unknown HPV, two ASCUS hrHPV, three ASC-H, 16 LSIL, and eight HSIL. The first colposcopy was performed an average of 12 (SD: 13.4) months with a median of 6 (range: 0–42) months from the initial Pap test and the LEEP/cone procedure was performed an average of 20 months with a median of 18 (range: 0–60) months from the initial Pap test. Among those who had an HSIL prior to colposcopy, 50% had CIN3 or SCC at the time of LEEP, while 19% of LSIL Pap tests had CIN3 at the time of LEEP.

Table 4.

Pathologic Results Before Loop Electrosurgical Excision and Follow-up Cytology Post-Loop Electrosurgical Excision, Sorted by Referral Pap

| Pap at enrollment | Referral Pap | Colposcopy months | Colposcopy pathology | Months to LEEP | LEEP pathology | Months of follow-up | Post-procedure | Final Pap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGC | AGC | 1 | Unsatisfactory | 18 | CIN1 | 42 | ASCUS- | |

| HSIL | ASC-H | 3 | CIN1 | 6 | CIN2 | 24 | ASCUS+ | |

| LSIL | ASC-H | 6 | CIN2 | 18 | CIN1 | 6 | NILM | |

| ASCUS | ASC-H | 24 | CIN2 | 30 | CIS | 42 | NILM | |

| ASC-H | ASC-H | 0 | CIN3 | 3 | CIN1 | 39 | NILM | |

| LSIL | ASC-H | 36 | CIN3 | 42 | CIN2 | 12 | LSIL | |

| ASCUS+ | ASC-H | 12 | CIN3 | 42 | CIN3 | 0 | ASC-H | |

| LSIL | ASCUS+ | — | — | 12 | CIN3 | 48 | NILM | |

| ASCUS+ | ASCUS+ | 3 | CIN1 | 6 | CIN1 | 36 | ASCUS− | |

| ASCUS+ | ASCUS+ | 0 | CIN1 | 6 | CIN1 | 42 | Hysterectomya | NILM |

| HSIL | ASCUS+ | 3 | Negative | 12 | CIN1 | 54 | ASCUS− | |

| HSIL | ASCUS+ | 3 | Negative | 24 | CIN2 | 30 | NILM | |

| ASCUS+ | ASCUS+ | 6 | Negative | 54 | Negative | 0 | ASCUS+ | |

| NILM | HSIL | 24 | CIN1 | 60 | CIN2 | 18 | LSIL | |

| HSIL | HSIL | 12 | CIN1 | 24 | CIN3 | 30 | NILM | |

| LSIL | HSIL | 12 | CIN1 | 24 | CIN3 | 30 | LEEP CIN2 | NILM |

| ASC-H | HSIL | 24 | CIN2 | 30 | CIN1 | 30 | NILM | |

| HSIL | HSIL | 6 | CIN2 | 3 | CIN2 | 45 | ASCUS+ | |

| HSIL | HSIL | 0 | CIN2 | 12 | CIN2 | 36 | NILM | |

| HSIL | HSIL | 12 | CIN2 | 12 | CIN3 | 48 | NILM | |

| LSIL | HSIL | 12 | CIN3 | 18 | CIN1 | 60 | NILM | |

| HSIL | HSIL | 1 | CIN3 | 6 | CIN2 | 60 | Hysterectomyb | ASCUS− |

| HSIL | HSIL | 6 | CIN3 | 12 | CIN3 | 18 | Cone CIN2 | NILM |

| LSIL | HSIL | 30 | CIN3 | 36 | SCC | 18 | LSIL | |

| NILM | LSIL | — | — | 18 | CIN2 | 66 | Hysterectomya | NILM |

| LSIL | LSIL | — | — | 6 | Negative | 72 | Hysterectomya | NILM |

| LSIL | LSIL | 18 | CIN1 | 54 | CIN2 | 0 | LSIL | |

| ASC-H | LSIL | 30 | CIN1 | 36 | Negative | 0 | LSIL | |

| LSIL | LSIL | 6 | CIN2 | 12 | CIN1 | 24 | ASCUS− | |

| LSIL | LSIL | 6 | CIN2 | 18 | CIN1 | 36 | NILM | |

| HSIL | LSIL | 42 | CIN2 | 48 | CIN2 | 0 | LSIL | |

| NILM | LSIL | 9 | CIN2 | 12 | CIN2 | 30 | NILM | |

| LSIL | LSIL | 6 | CIN2 | 6 | CIN3 | 54 | LEEP at 12 months CIN3 | NILM |

| LSIL | LSIL | 3 | CIN2 | 6 | CIN3 | 36 | LSIL | |

| LSIL | LSIL | 18 | CIN3 | 18 | CIN1 | 18 | NILM | |

| ASCUS | LSIL | 12 | CIN3 | 24 | CIN2 | 12 | NILM | |

| LSIL | LSIL | 3 | CIN3 | 3 | CIN2 | 21 | LSIL | |

| LSIL | LSIL | 6 | CIN3 | 6 | CIN2 | 54 | ASCUS+ | |

| LSIL | LSIL | 3 | CIN3 | 6 | CIN3 | 24 | LSIL | |

| NILM | LSIL | 3 | Unsatisfactory | 30 | Negative | 60 | ASCUS− | |

| SCC | SCC | CIN3 | 0 | CIS | 36 | Excision showing CIS, then LEEP CIN1 | ASCUS+ |

Hysterectomy for bleeding or fibroids.

Hysterectomy for dysplasia.

Overall, among those who underwent LEEP, 0/1 (0%) AGC, 2/6 (33%) ASCUS-positive hrHPV, 4/6(67%) ASC-H, 10/16 (63%) LSIL, and 9/11 (82%) with HSIL had CIN2 or greater on LEEP pathology, and the one with SCC on cervical cytology had carcinoma in situ on LEEP. A cervical cytology of HSIL was associated with a high-grade CIN lesion on follow-up. Three developed SCC, one at the start of the study interval, one after 30 months, and one at 36 months. One adenocarcinoma was detected incidentally at 7 months during a hysterectomy for menorrhagia. Four of those with LEEPs had hysterectomies, two for bleeding, one for fibroids, and one for dysplasia.

The average time between colposcopy and LEEP for the individuals with similar histology at colposcopy and LEEP was 10.8±15 months. For those who had a lower grade in LEEP compared to colposcopy, the average time was 5.5±4.4 months and for those who had a higher grade in LEEP compared to colposcopy, the median times was 9.5±10.9 months. At the end of the study for these 41 individuals who had a surgical procedure, the cervical cytology showed NILM (49%), LSIL (22%), ASCUS hrHPV negative (15%), ASCUS hrHPV positive (12%), and ASC-H (2%). None had HSIL at the end of the follow-up.

There were also 44 patients who should have had a colposcopy but did not get the indicated follow-up. There were four patients with AGC: two with a final Pap test with AGC and two with a negative Pap test. There were seven patients with ASC-H: three with final Pap test of ASC-H and four with a negative Pap test. One had ASCUS unknown HPV with a final Pap test of ASCUS-positive hrHPV. There were seven patients who developed ASCUS-positive hrHPV: two with a final Pap test of ASCUS-positive hrHPV and two with negative Pap tests. Finally there were 25 patients who developed LSIL: five with a final pap of LSIL, one with ASCUS (who had had a negative hrHPV in the past), two with ASCUS-positive hrHPV, and 17 with a negative Pap test. Additionally there were 20 patients with ASCUS who may have had a Pap test indicated. Of those 19 had a final Pap test, which was negative, and one who had ASCUS unknown HPV as the final Pap test but had prior negative hrHPV testing.

Discussion

We present a longitudinal follow-up of 309 HIV-infected women undergoing cervical cytology screening in the antiretroviral era when cART is widely available and easily tolerated from our outpatient HIV clinic with a median follow-up of 5 years. Nearly half of (45%) of our cohort had normal Pap tests at the start of the study and nearly a quarter of our cohort (23%) had persistently negative Pap tests during the study period. Of note is that fact that 40% of LSIL, ASC-H, and HSIL regressed without intervention. This was a greater rate of regression than that reported by Ahdieh-Grant in 200423 from HIV-infected women before and after the introduction of antiretrovirals. Their reported rate of regression not on cART was 0% and for those on cART was 12.5%. In a model controlling for detectable viral load, only initial CD4+ above 200 cells/mL was significantly associated with regression or remaining normal.

Over a median of 60 months, progression occurred in 8% of those with LSIL, 5% of ASC-H, and 4% of HSIL. This represents a lower rate of progression compared to data from Soweto that reported that among 1,074 HIV-infected women with baseline normal or LSIL cytology and followed for 2.5 years, 10.5% (95% CI: 8.7–12.4) progressed to a higher lesion.21 This may be due to higher rates of viral load suppression and CD4+ cell counts among the women and improved and more aggressive gynecological care.

It is interesting that Fig. 1 shows such similar rates of progression, regression, and persistence among the SILs. This may be because those who had surgical intervention were not included in the follow-up analysis. Table 2 and Fig. 1 show the data including those with surgical data.

Among the individuals who underwent LEEP, approximately half had high-grade lesions (CIN 2 or higher), with three cancers diagnosed (the fourth was found incidentally on hysterectomy). Most of the preceding Pap tests were high-grade or ASCUS-positive hrHPV. This highlights the need for close follow-up of these patients. A previous Pap test with LSIL in contrast had few high-grade lesions and no cancers on follow-up. Of the 44 with a Pap test indicating the need for follow-up but who did not have a follow-up Pap test, two-thirds of those with high grade or ASCUS with hrHPV continued to have a lesion, indicating the need for colposcopy. But only 8/25 of those with LSIL persisted, which suggests LSIL may not need as close monitoring. The majority of our patients [23/39 (59%)] had a negative final follow-up Pap test, which is a higher rate of negative Pap tests than reported before cART was consistently in use.24

There are limitations in our study that are inherent to retrospective studies: the inability to control for certain confounders (e.g., the number of partners, condoms, or hormone therapy and incomplete HPV testing, the number of Pap tests before enrolling in the study, the age at first sexual activity). Although a thorough review of the records was performed, a few patients with prior procedures at other institutions could have been missed.

Conclusions

In our cohort that comprised women consistently attending an HIV follow-up clinic with long-term HIV infection and who had more than four Pap tests, we found that they are older than those in other studies reported in the literature. A quarter had persistently normal Pap tests; 64 of those 305 followed regressed and 50 progressed. This is likely because cART is associated with higher CD4 counts and therefore more regression. Of interest, at colposcopy among the patients with LSIL, only 12% showed premalignant lesions. More studies are needed to identify the colposcopy strategy for LSIL patients. Consideration of the combined use of HPV testing and Pap screening for LSIL patients given their otherwise low rates of progression seems warranted. Newer guidelines are needed for HIV-seropositive women who are in care, have improved CD4, and have persistently negative Pap tests. None of our patients with initial NILM or ASCUS-negative hrHPV developed cancer and likely those low-risk patients could have longer follow-up intervals, extending to every 2–3 years instead of yearly.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients, providers, and staff of the Ponce Clinic. This work was supported by the Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) at Emory University (P30AI05409). We appreciate the work done by our data abstractors Jamie Nguyen, Divien Nguyen, and Karen Chu.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Friedmann W, et al. : [HIV infections and cervical neoplasms]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 1989;49(11):997–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schafer A, et al. : The increased frequency of cervical dysplasia-neoplasia in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus is related to the degree of immunosuppression. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164(2):593–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright TC Jr, et al. : Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women infected with human immunodeficiency virus: Prevalence, risk factors, and validity of Papanicolaou smears. New York Cervical Disease Study. Obstet Gynecol 1994;84(4):591–597 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henry-Stanley MJ, et al. : Cervical cytology findings in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Diagn Cytopathol 1993;9(5):508–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adachi A, et al. : Women with human immunodeficiency virus infection and abnormal Papanicolaou smears: A prospective study of colposcopy and clinical outcome. Obstet Gynecol 1993;81(3):372–377 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anorlu RI, et al. : Prevalence of abnormal cervical smears among patients with HIV in Lagos, Nigeria. West Afr J Med 2007;26(2):143–147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris TG, et al. : Insulin-like growth factor axis and oncogenic human papillomavirus natural history. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17(1):245–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maiman M, et al. : Human immunodeficiency virus infection and cervical neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 1990;38(3):377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maiman M, et al. : Human immunodeficiency virus infection and invasive cervical carcinoma. Cancer 1993;71(2):402–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denslow SA, et al. : Incidence and progression of cervical lesions in women with HIV: A systematic global review. Int J STD AIDS 2014;25(3):163–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker DA: Management of the female HIV-infected patient. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1994;10(8):935–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denenberg R: Cervical cancer and women with HIV. GMHC Treat Issues 1997;11(7–8):10–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandelblatt JS, et al. : Association between HIV infection and cervical neoplasia: Implications for clinical care of women at risk for both conditions. AIDS, 1992;6(2):173–178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araujo AC, et al. : Incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in a cohort of HIV-infected women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;117(3):211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Firnhaber C, et al. : Highly active antiretroviral therapy and cervical dysplasia in HIV-positive women in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2012;15(2):17382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minkoff H, et al. : Influence of adherent and effective antiretroviral therapy use on human papillomavirus infection and squamous intraepithelial lesions in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Infect Dis 2010;201(5):681–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piketty C, et al. : Human papillomavirus-related cervical and anal disease in HIV-infected individuals in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2005;2(3):140–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massad LS, et al. : Effect of antiretroviral therapy on the incidence of genital warts and vulvar neoplasia among women with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190(5):1241–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrestha S, et al. : The impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on prevalence and incidence of cervical human papillomavirus infections in HIV-positive adolescents. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paramsothy P, et al. : The effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on human papillomavirus clearance and cervical cytology. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113(1):26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright TC Jr., et al. : 2001 Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Women with Cervical Cytological Abnormalities. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2002;6(2):127–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Omar T, et al. : Progression and regression of premalignant cervical lesions in HIV-infected women from Soweto: A prospective cohort. AIDS 2011;25:87–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahdieh-Grant L, et al. : Highly active antiretroviral therapy and cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96(14):1070–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massad LS, et al. : Outcomes after treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia among women with HIV. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2007;11(2):90–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]