Significance

The presence of cytosolic DNA in mammalian cells signifies microbial invasions and triggers the DNA sensor protein cGAS to produce the second messenger molecule 2′3′-cGAMP, which elicits innate immune responses by binding to and activating the homodimerized adaptor protein STING. Here we show that the high affinity of the asymmetric ligand 2′3′-cGAMP to the symmetric dimer of STING originates from its unique mixed phosphodiester linkages. 2′3′-cGAMP, but not its linkage isomers, adopts an organized free-ligand conformation that resembles the STING-bound conformation and pays low energy costs in changing into the active conformation. Whereas biological structural studies have focused on analyses of protein conformations, our results demonstrate that analyses of free-ligand conformations can be equally important in understanding protein–ligand interactions.

Keywords: cGAMP, STING, phosphodiester linkage, ligand conformation

Abstract

Cyclic GMP-AMP containing a unique combination of mixed phosphodiester linkages (2′3′-cGAMP) is an endogenous second messenger molecule that activates the type-I IFN pathway upon binding to the homodimer of the adaptor protein STING on the surface of endoplasmic reticulum membrane. However, the preferential binding of the asymmetric ligand 2′3′-cGAMP to the symmetric dimer of STING represents a physicochemical enigma. Here we show that 2′3′-cGAMP, but not its linkage isomers, adopts an organized free-ligand conformation that resembles the STING-bound conformation and pays low entropy and enthalpy costs in converting into the active conformation. Our results demonstrate that analyses of free-ligand conformations can be as important as analyses of protein conformations in understanding protein–ligand interactions.

The presence of cytosolic DNA in mammalian cells is a danger signal that triggers the production of second messenger cGAMP by the DNA sensor protein cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) (1, 2). cGAMP then activates the adaptor protein stimulator of IFN genes (STING, also known as TMEM173, MITA, ERIS, or MPYS) and induces the translocation of STING from the endoplasmic reticulum membrane to the Golgi, where it then recruits IκB kinase and TANK-binding kinase 1 (3, 4). The transcription factors nuclear factor κB and IFN regulatory factor 3 are subsequently activated, leading to the production of antiviral and proinflammatory cytokines, including type I interferons (IFNs). This cGAMP-mediated immune response is a fundamental defense mechanism against viral infection (5–7), making cGAMP and its structural derivatives potential vaccine adjuvants and immunotherapeutic agents against cancer (6, 8).

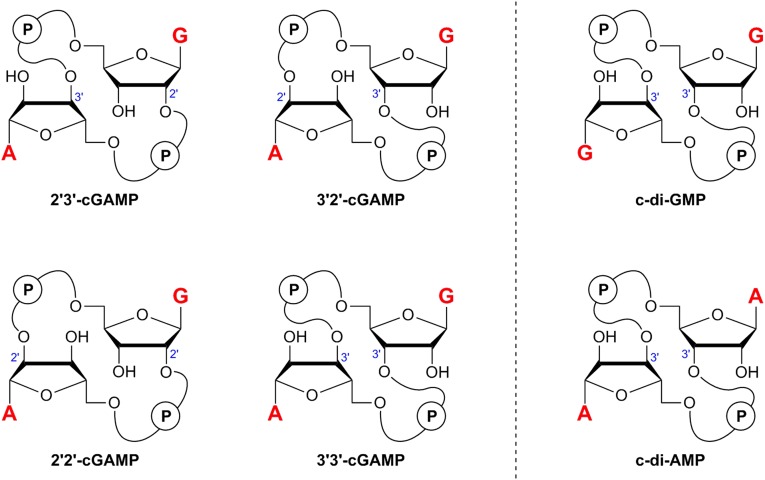

cGAMP is a hybrid cyclic dinucleotide that contains a guanosine unit and an adenosine unit joined by two phosphates in a macrocycle (Fig. 1). In contrast with the well-known bacterial signaling molecules cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) and cyclic di-AMP (c-di-AMP) that contain a pair of (3′→5′)-phosphodiester linkages, the endogenous cGAMP molecule in mammalian cells contains unprecedented mixed phosphodiester linkages (9–12). Its two phosphate groups connect the two nucleosides from the 2′- and 5′ positions of guanosine and the 3′- and 5′ positions of adenosine. Denoted as 2′3′-cGAMP, this asymmetric ligand binds to the symmetric dimer of STING with an affinity significantly higher than its linkage isomers 2′2′-cGAMP, 3′2′-cGAMP, and 3′3′-cGAMP (SI Appendix, Table S1) (9). Notably, 3′3′-cGAMP has been found to be produced by certain bacteria (13, 14), whereas 2′2′-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP have yet to be found in nature. Recent studies have revealed the molecular basis for the selective formation of the mixed 2′3′-phosphodiester linkages by cGAS (10, 14–18). However, the function of this linkage isomerism remained unclear and crystallographic studies of the STING/cGAMP complexes provided no insight (9, 19). Here we show that the preferred binding of 2′3′-cGAMP originates from its favorable free-ligand instead of protein-bound conformation. 2′3′-cGAMP, but not its linkage isomers, adopts an organized free-ligand conformation that resembles the STING-bound conformation and pays low energy costs in changing into the active conformation to bind to STING. The contribution of free-ligand conformation is commonly overlooked in biomolecular studies but plays an important role in the linkage selectivity of the STING/cGAMP complexes.

Fig. 1.

Structures of cyclic dinucleotides. cGAMP molecules are hybrid cyclic dinucleotides comprising a GMP and an AMP unit whereas c-di-GMP and c-di-AMP are homodimers of GMP and AMP, respectively. In contrast with the bacterial signaling molecules 3′3′-cGAMP, c-di-GMP, and c-di-AMP that contain a pair of homogeneous (3′→5′) phosphodiester linkages, the mammalian second messenger 2′3′-cGAMP contains unique G(2′→5′)/A(3′→5′) phosphodiester linkages.

Results and Discussion

2′3′-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP Bind to STING with Indistinguishable Binding Modes.

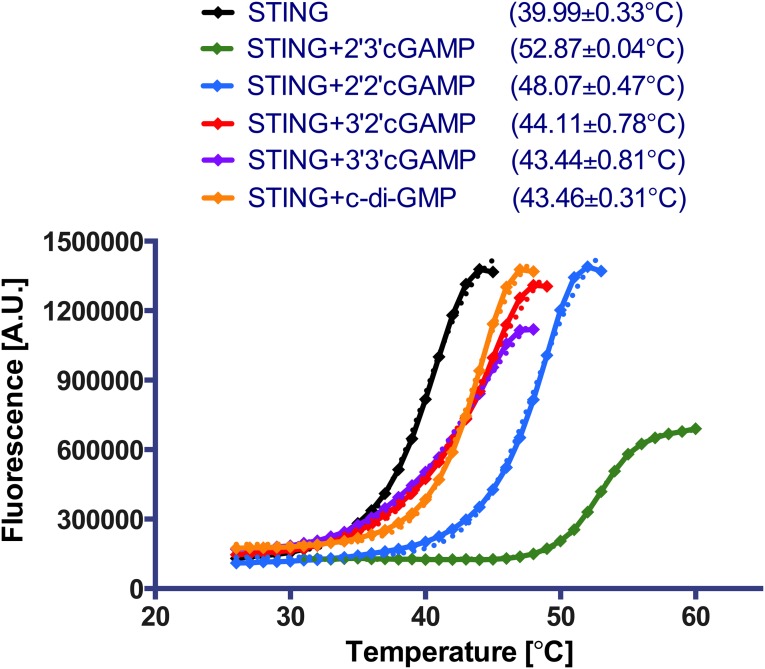

We used a combination of thermodynamic and structural approaches to understand the molecular basis for the selective binding of 2′3′-cGAMP by STING. We first corroborated the isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)-derived relative binding affinities of the cGAMP molecules toward STING (SI Appendix, Table S1) (9) by differential scanning fluorometry (DSF) [as the thermal stability and binding affinity generally correlate well for protein–ligand complexes (20, 21)]. We found that the melting temperature (Tm) of STING increases most significantly in the presence of 2′3′-cGAMP followed by 2′2′-cGAMP (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Consistent with the results of our previous ITC studies, the order of stabilization is 2′3′-cGAMP > 2′2′-cGAMP > 3′2′-cGAMP ∼ 3′3′-cGAMP ∼ c-di-GMP.

Fig. 2.

Thermostabilization of STING by different cyclic dinucleotides. The melting curves of STING (10 μM) were recorded in the absence and presence of 100 μM cGAMP isomers or c-di-GMP. The Tm values (shown with 95% confidence intervals) were determined by fitting the data to a Boltzmann sigmoidal equation. Representative results of three independent experiments are shown.

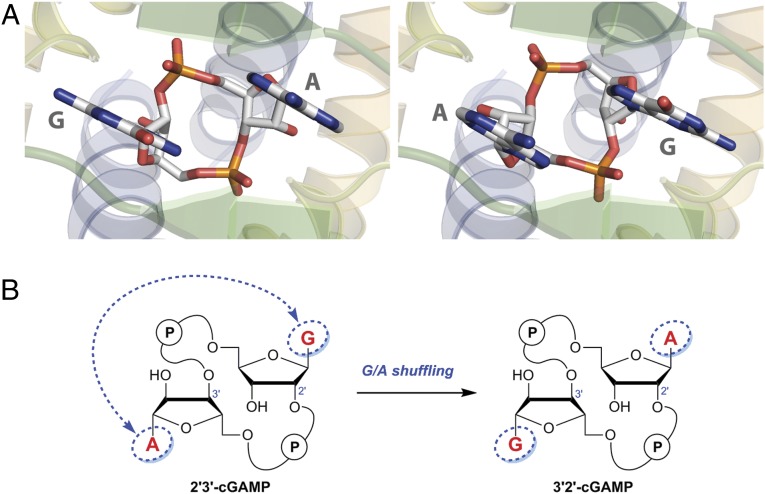

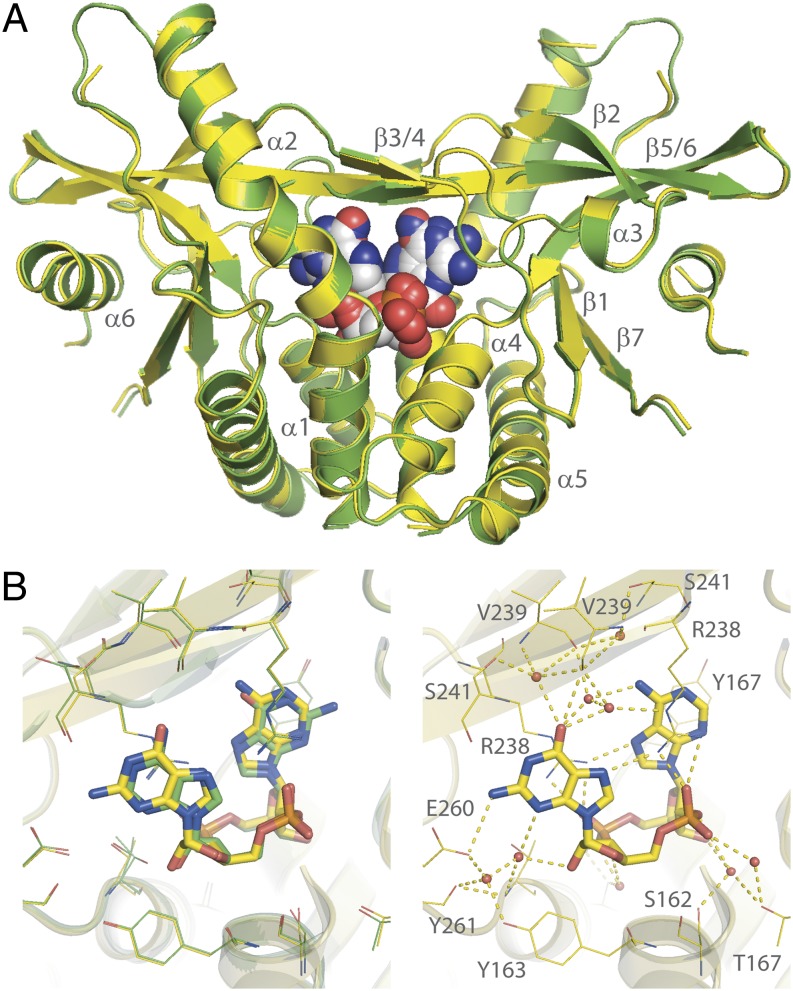

The preferred binding of 2′3′-cGAMP over 3′2′-cGAMP is particularly perplexing because the crystal structures of the STING/2′3′-cGAMP complexes [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID codes 4KSY and 4LOH)] suggest that 2′3′-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP would have the same binding interactions with STING. Specifically, the asymmetric nature of 2′3′-cGAMP renders it binding to the symmetric STING dimer in two alternative orientations (9, 19) (Fig. 3A). As the ligand and the protein share a C2 axis, the two purine base groups are placed at the same positions in these two orientations. An exchange of the guanine and adenine groups would result in essentially no change of the protein–ligand interactions but convert 2′3′-cGAMP into 3′2′-cGAMP (Fig. 3B). This prediction was confirmed by crystallographic studies of the STING/3′2′-cGAMP complex (SI Appendix, Table S2). 3′2′-cGAMP induces the same conformational changes for the C-terminal domain (CTD) of STING to convert it from the inactive “open” state into the active “closed” state. The crystal structures of STING in complex with 2′3′-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP are nearly identical (Fig. 4A). Both cGAMP molecules sit at the same position of the binding pocket, forming the same hydrogen bond network and π‒π stacking interactions with STING (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3.

Crystal structures of STING/2′3′-cGAMP complexes suggest that 2′3′-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP would have the same binding interactions with STING. (A) 2′3′-cGAMP binds to STING in two alternative orientations with the two purine base groups placed at the same positions (PDB ID code 4KSY) (9). (B) Shuffling the guanine and adenine groups converts 2′3′-cGAMP into 3′2′-cGAMP.

Fig. 4.

STING binds to 2′3′-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP with indistinguishable binding modes. (A) STING undergoes the same conformational change upon binding to 2′3′-cGAMP (green, PDB ID code 4KSY) (9) and 3′2′-cGAMP (yellow, PDB ID code 5BQX). (B) 2′3′-cGAMP (green) and 3′2′-cGAMP (yellow) bind to STING with nearly identical hydrogen bond networks.

2′3′-cGAMP Adopts an Organized Free-Ligand Conformation.

Analysis of the thermodynamic data provided useful information on the origin of the linkage selectivity. Although the total binding energy (ΔGtotal) is determined by enthalpy (ΔHtotal) and entropy (ΔStotal) terms (Eq. 1), our ITC data indicate that the binding of STING to 2′3′-cGAMP or 3′2′-cGAMP is entropy-driven and both bindings are nearly thermally neutral (SI Appendix, Table S1) (9). This observation is consistent with results of the crystallographic studies described above that 2′3′-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP interact with STING through essentially the same hydrogen bond networks, suggestive of ΔHSTING/2′3′-cGAMP ∼ ΔHSTING/3′2′-cGAMP.

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

We considered that the bindings of 2′3′-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP by STING are driven by the release of water molecules from the large binding pocket of STING. Because STING undergoes the same conformational change and both STING-bound ligands have the same volume (∼520 Å3), ΔSprotein and ΔSwater should be comparable in both cases. Consequently, the linkage selectivity must originate from differential ΔSligand (Eq. 2). Following the observation that 2′3-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP adopt the same STING-bound conformation (S2′3′-cGAMP(bound) ∼ S3′2′-cGAMP(bound)), we suspected that 2′3′-cGAMP exists in an organized and favorable free-ligand conformation that requires significantly less entropy cost to bind to STING (S2′3′-cGAMP(free) << S3′2′-cGAMP(free)) (Eq. 3).

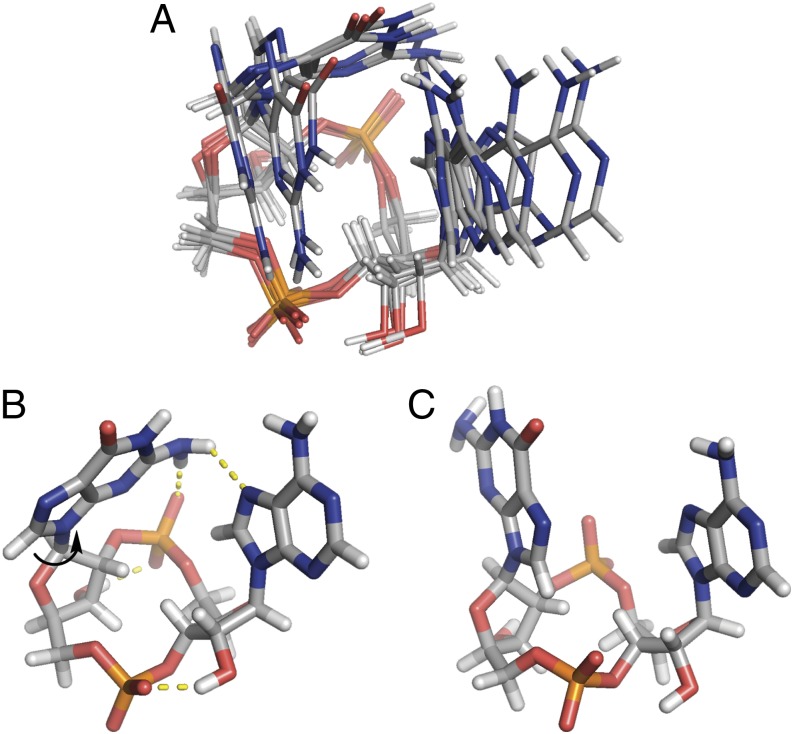

To test this hypothesis, we used NMR and computational analyses to determine the free-ligand structures of the cGAMP molecules (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S4 and Tables S3–S13). We found that 2′3′-cGAMP exists in six closely related conformations giving rise to an equilibrium geometry that highly resembles its STING-bound conformation (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Table S9). The G(2′→5′) phosphodiester linkage allowed for the formation of a strong hydrogen bond between the guanine amino group and the adenosine phosphate group and a weak hydrogen bond between the guanine amino group and the adenine group. These two hydrogen bonds hold 2′3′-cGAMP in a closed geometry that requires only a small conformational change to bind to STING. A rotation of the guanine group by ∼90° readily converts the inactive free-ligand conformation into the STING-bound conformation. Although this motion involves the disruption of the two guanine-derived hydrogen bonds, this process is kinetically accessible as evinced by the conformational analysis. The pyramidal geometry of the exocyclic amino groups is also in good accordance with the increasing evidence for the nonplanar hydrogen bond interactions of purines (22).

Fig. 5.

Conformational analyses of the mammalian 2′3′-cGAMP molecule. 2′3′-cGAMP exists in (A) a set of organized conformations in solution, leading to (B) a closed equilibrium geometry that highly resembles (C) the STING-bound conformation.

3′2′-cGAMP and 3′3′-cGAMP Adopt Highly Flexible Free-Ligand Conformations.

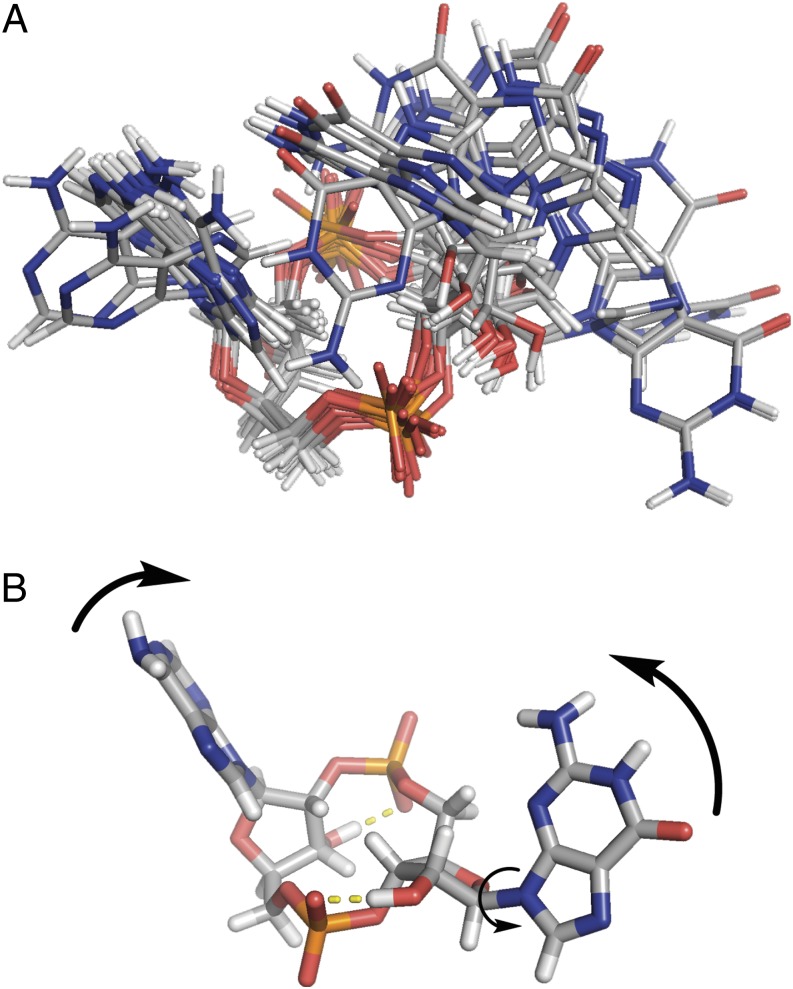

Unlike 2′3′-cGAMP, 3′2′-cGAMP adopts an open geometry comprising 14 more random conformations (Fig. 6 and SI Appendix, Table S10). Although 3′2′-cGAMP maintains the same hydrogen bond network within the carbohydrate macrocycle as 2′3′-cGAMP, it lacks the purine-base–derived hydrogen bonds to “fold” the molecule and consequently has high degrees of freedom. To bind to STING, 3′2′-cGAMP needs to undergo a large conformational change to bring the two purine bases into parallel positions. The unfavorable entropy change associated with this motion leads to the lower binding affinity of 3′2′-cGAMP to STING.

Fig. 6.

Conformational analyses of the linkage isomer 3′2′-cGAMP. (A) 3′2′-cGAMP has high degrees of freedom as a free ligand with (B) an open equilibrium geometry that requires a large conformational change to bind to STING.

For cGAMP molecules with symmetric phosphodiester linkages, 3′3′-cGAMP binds to STING weakly whereas 2′2′-cGAMP has a moderate affinity toward STING. A previous study revealed that STING undergoes the same conformational change upon binding to 2′2′-cGAMP and 3′3′-cGAMP and exerts the same protein‒ligand interactions (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) (PDB ID codes 4LOI and 4LOK) (19). Therefore, we expect that the bindings of 2′2′-cGAMP and 3′3′-cGAMP are largely influenced by their solution conformations as well.

The bacterial signaling molecule 3′3′-cGAMP contains a pair of homogeneous (3′→5′) phosphodiester linkages. The circular dichroism (CD) data (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) (9) suggest that it adopts an even more “open” conformation as a free ligand. ITC data also indicate that the binding of 3′3′-cGAMP by STING is less entropically favored than that of 3′2′-cGAMP. Although this observation is consistent with the hypothesis that a larger conformational change than 3′2′-cGAMP is involved in the binding of 3′3′-cGAMP by STING, the overlap of key proton NMR signals of 3′3′-cGAMP precludes its detailed structural studies.

2,2-cGAMP Adopts a Rigid Free-Ligand Conformation.

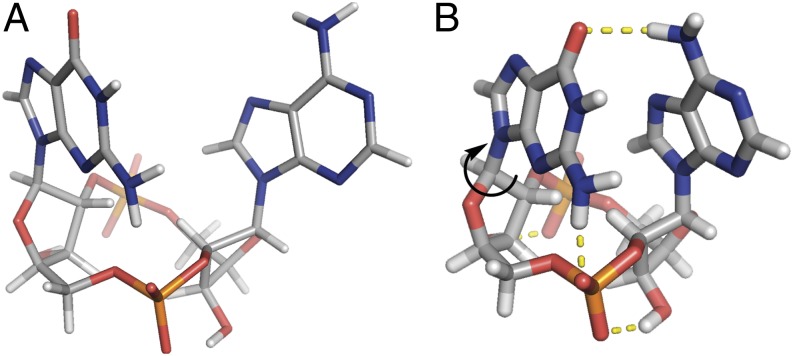

According to our NMR studies, 2′2′-cGAMP also adopts a closed conformation in solution. Its CD spectrum resembles that of 2′3′-cGAMP in the near-UV region where the purine base groups absorb (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) (9). However, NMR-based conformational studies indicate that the purine base groups of 2′2′-cGAMP establish an intramolecular hydrogen bond network different from that of 2′3′-cGAMP (Fig. 7). The guanine carbonyl group forms a strong hydrogen bond with the adenine amino group and the guanine amino group forms a strong hydrogen bond with the guanosine phosphate group to lock this purine base unit from two sides. The transition of 2′2′-cGAMP from solution into the binding pocket of STING involves disruption of these strong hydrogen bonds and the π‒π stacking interaction between the two purine base groups followed by a rotation of the guanine group by ∼180°. Consistent with the observed large entropy gain associated with the binding of 2′2′-cGAMP by STING, this cage-like structure is the only conformation both in solution and in gas phase. However, the associated enthalpy cost offsets the entropic advantage, rendering 2′2′-cGAMP a moderate ligand for STING.

Fig. 7.

Conformational analyses of the linkage isomer 2′2′-cGAMP. The strong hydrogen bond network holds 2′2′-cGAMP in a closed conformation as a free ligand both (A) in gas phase and (B) in solution.

Conclusion

Enthalpic factors are the common determinants of ligand specificity in protein binding. Current structural studies thus typically focus on the analysis of protein–ligand interactions. However, for STING/cGAMP binding, the entropic factors of the free ligands can provide a large difference in binding affinities even with the same protein–ligand interactions. The fine balance between the entropy gain and the enthalpy loss in converting the inactive free-ligand conformation into the active protein-bound conformation underlies the selective binding of STING to the mammalian cGAMP molecule that contains unusual mixed G(2′→5′)/A(3′→5′) phosphodiester linkages. Presently, there is tremendous interest in developing small molecule agonists of STING as immune therapeutics and vaccine adjuvants. Our results suggest that consideration of free-ligand conformations in conjunction with the protein–ligand interactions is important for developing cGAMP analogs as potent and specific STING ligands.

Materials and Methods

DSF Experiments.

Recombinant human STING CTD (139‒379) was expressed and purified as described previously (9). The purified hSTING CTD was then mixed with or without different concentrations of cGAMP isomers in each well of a 96-well plate, in the presence of SYPRO orange (Invitrogen) dye (1:1,000 dilution). Fluorescence signals were recorded on a ViiA7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with its SYBR mode using filters Ex/Em: 455–485/505–535nM. Samples were subjected to a temperature gradient from 15 to 80 °C, with an increment of 1 °C per step followed by holding at the same temperature for 15 s. The Tm values were determined by fitting the melting curves to a Boltzmann sigmoidal equation using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software.

Crystallographic Studies.

Recombinant hSTING CTD (139‒379) was concentrated to 12.5 mg/mL in buffer containing 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP; 3′2′-cGAMP was then mixed with STING CTD in a 1.2:1 molar ratio followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. Crystals were grown at 20 °C by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. The complex yielded needle-cluster crystals in buffer containing 0.2 M ammonium acetate, 0.1 M trisodium citrate (pH 5.8), and 25% (wt/vol) PEG 4,000. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by further optimization through microseeding. The crystals were cryoprotected with crystallization buffer plus 20% ethylene glycol before being flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Structural Biology Center (Beamline 19ID) at Argonne National Laboratory. Diffraction data were processed with the HKL 3000 package (23). The structure was solved by molecular replacement from the structure of the apo hSTING (PDB ID code 4F9E), using the program suite PHENIX (24) and Coot (25). Refinement was performed after excluding 10% of the data for the R-free calculation. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S2. The coordinates have been deposited in the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics protein data bank under PDB ID code 5BQX.

NMR Studies.

The cGAMP molecules were synthesized as described previously (9). All NMR experiments were performed on a Varian Inova-400 or Inova-600 spectrometer with a solution of cGAMP (9 mM) in deuterated pH 7.4 buffer (30 mM). The cGAMP molecules were dissolved in NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4/D2O, evaporated, and then redissolved in D2O. No aggregation was observed for all cGAMP molecules based on 1D 1H NMR and temperature-dependent UV spectra. The NMR peaks were assigned based on 1H/1H gradient correlation spectroscopy (gCOSY), 1H/13C heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy (HSQC), and 1H/13C heteronuclear multiple bond correlation spectroscopy (HMBC) experiments. The distance constraints used to calculate the free-ligand conformation of the cGAMP molecules were obtained from rotating-frame Overhauser spectroscopy (ROESY) experiments. The proper mixing time for the ROESY experiments was determined by monitoring the build-up curves for the intensities of significant cross-peaks in ROESY with a mixing time ranging from 50 to 600 ms (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S4). The mixing times used in the final ROESY experiments are 350, 300, and 250 ms for 2′3′-cGAMP, 3′2′-cGAMP, and 2′2′-cGAMP, respectively. For 2′3′-cGAMP and 3′2′-cGAMP, the guanosine methylene group was used as the reference with an interproton distance of 1.78 Å to calculate the distance constraints following (Intensity) α (distance)–6. For 2′2′-cGAMP, the adenosine methylene group was used as the reference.

Computational Studies.

All computational studies were carried out with Spartan '04 or '14. Conformational analyses were carried out by molecular mechanics force field (MMFF) with distance constraints obtained from the NMR studies. The geometries of the unique conformers were then optimized without distance constraints using Hartree‒Fock approximation with the 3–21G basis set. The resultant duplicated conformers were removed after alignment analyses with PyMOL 1.7. Equilibrium geometries were first calculated with distance constraints using the AM1 semiempirical method starting from the MMFF conformer geometry. The results were then optimized without distance constraints using density functional theory calculations with the Becke, three-parameter, Lee–Yang–Parr (B3LYP) functional and the 6–31G** basis set. The results were further refined by B3LYP/6–31+G* calculations. The computed geometries of the cGAMP molecules are consistent with the N/S conformations of the ribose units predicted by the observed coupling constants (26). The empirical and calculated interproton distances also agree with each other. The data for the dihedral angle-based conformation analyses are provided in SI Appendix, Tables S3–S5. The root-mean-square distances for the empirical and computed interproton distances are given in SI Appendix, Tables S6–S8. The relative energies and the statistics of the alignment of the conformers are listed in SI Appendix, Tables S9 and S10. The Cartesian coordinates of the computed equilibrium geometries of the cGAMP molecules are given in SI Appendix, Tables S11–S13.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yi-chun Kuo and Prof. Xuewu Zhang for assistance with X-ray data collection and Dr. Xu Zhang for the ITC data. Results shown in this report are derived from work performed at Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source. Argonne is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the US Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. Financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health through Grants R01-GM-079554 and R01-AI-093967 and the Welch Foundation through Grant I-1868. J.W. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research Fellow. Z.J.C. is an Investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute and C.C. is a Southwestern Medical Foundation Scholar in Biomedical Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 5BQX).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1507317112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339(6121):786–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1232458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu J, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. 2013;339(6121):826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1229963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai X, Chiu Y-H, Chen ZJ. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing and signaling. Mol Cell. 2014;54(2):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu J, Chen ZJ. Innate immune sensing and signaling of cytosolic nucleic acids. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:461–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao D, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science. 2013;341(6148):903–906. doi: 10.1126/science.1240933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X-D, et al. Pivotal roles of cGAS-cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. Science. 2013;341(6152):1390–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1244040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoggins JW, et al. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature. 2014;505(7485):691–695. doi: 10.1038/nature12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng L, et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing promotes radiation-induced type I interferon-dependent antitumor immunity in immunogenic tumors. Immunity. 2014;41(5):843–852. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP containing mixed phosphodiester linkages is an endogenous high-affinity ligand for STING. Mol Cell. 2013;51(2):226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao P, et al. Cyclic [G(2′,5′)pA(3′,5′)p] is the metazoan second messenger produced by DNA-activated cyclic GMP-AMP synthase. Cell. 2013;153(5):1094–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ablasser A, et al. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature. 2013;498(7454):380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diner EJ, et al. The innate immune DNA sensor cGAS produces a noncanonical cyclic dinucleotide that activates human STING. Cell Reports. 2013;3(5):1355–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies BW, Bogard RW, Young TS, Mekalanos JJ. Coordinated regulation of accessory genetic elements produces cyclic di-nucleotides for V. cholerae virulence. Cell. 2012;149(2):358–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kranzusch PJ, et al. Structure-guided reprogramming of human cGAS dinucleotide linkage specificity. Cell. 2014;158(5):1011–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, et al. The cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS forms an oligomeric complex with DNA and undergoes switch-like conformational changes in the activation loop. Cell Reports. 2014;6(3):421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Civril F, et al. Structural mechanism of cytosolic DNA sensing by cGAS. Nature. 2013;498(7454):332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is activated by double-stranded DNA-induced oligomerization. Immunity. 2013;39(6):1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kranzusch PJ, Lee AS-Y, Berger JM, Doudna JA. Structure of human cGAS reveals a conserved family of second-messenger enzymes in innate immunity. Cell Reports. 2013;3(5):1362–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao P, et al. Structure-function analysis of STING activation by c[G(2′,5′)pA(3′,5′)p] and targeting by antiviral DMXAA. Cell. 2013;154(4):748–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(9):2212–2221. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matulis D, Kranz JK, Salemme FR, Todd MJ. Thermodynamic stability of carbonic anhydrase: Measurements of binding affinity and stoichiometry using ThermoFluor. Biochemistry. 2005;44(13):5258–5266. doi: 10.1021/bi048135v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukherjee S, Majumdar S, Bhattacharyya D. Role of hydrogen bonds in protein-DNA recognition: Effect of nonplanar amino groups. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109(20):10484–10492. doi: 10.1021/jp0446231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: The integration of data reduction and structure solution—from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 8):859–866. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altona C, Sundaralingam M. Conformational analysis of the sugar ring in nucleosides and nucleotides. Improved method for the interpretation of proton magnetic resonance coupling constants. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95(7):2333–2344. doi: 10.1021/ja00788a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.