Abstract

Ectopic mineralization - inappropriate biomineralization in soft tissues - is a frequent finding in physiological aging processes and several common disorders, which can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Further, pathologic mineralization is seen in several rare genetic disorders, which often present life-threatening phenotypes. These disorders are classified based on the mechanisms through which the mineralization occurs: metastatic or dystrophic calcification or ectopic ossification. Underlying mechanisms have been extensively studied, which resulted in several hypotheses regarding the etiology of mineralization in the extracellular matrix of soft tissue. These hypotheses include intracellular and extracellular mechanisms, such as the formation of matrix vesicles, aberrant osteogenic and chondrogenic signaling, apoptosis and oxidative stress. Though coherence between the different findings is not always clear, current insights have led to improvement of the diagnosis and management of ectopic mineralization patients, thus translating pathogenetic knowledge (variome) to the phenotype (phenome). In this review, we will focus on the clinical presentation, pathogenesis and management of primary genetic soft tissue mineralization disorders. As examples of dystrophic calcification disorders Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Generalized arterial calcification of infancy, Keutel syndrome, Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification and Arterial calcification due to CD73 (NT5E) deficiency will be discussed. Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis will be reviewed as an example of mineralization disorders caused by metastatic calcification.

Keywords: Ectopic mineralization, Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like syndrome, Generalized arterial calcification of infancy, Keutel syndrome, Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification, Arterial calcification due to CD73 deficiency, Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis, Etiology, Phenotype

Core tip: Ectopic mineralization disorders represent a broad range of phenotypically heterogenous diseases, often leading to significant morbidity and mortality. Involving a complex interplay between different pro-osteogenic mediators and inhibitors of calcification, the mechanisms of ectopic mineralization are progressively being unveiled. Though current knowledge is beyond any doubt the tip of the proverbial iceberg, insights already have significant implications in the diagnosis and daily management of these patients. As such, ectopic mineralization diseases are a fine example of translating variome data to the clinic. Here, we will discuss prototype hereditary ectopic calcification diseases with respect to their presentation, diagnosis and management.

INTRODUCTION

Physiological biomineralization is a complex multifactorial metabolic process, which in normal conditions is restricted to the extracellular matrix (ECM) of specific body structures, namely the bones, teeth, hypertrophic growth plate cartilage and calcified articular cartilage[1,2]. The intracellular and extracellular mechanisms, underlying physiological biomineralization, rely on a balanced interplay between mineralization inhibitors and propagators (Figure 1)[2,3]. Although in physiological circumstances calcium and inorganic phosphate (Pi) concentrations exceed their solubility in most human tissues, this does not result in mineralization of soft tissues, suggesting that these tissues possess regulatory mechanisms preventing mineral deposition. Mineralizing tissues must be able to modulate these mechanisms to enable calcification[2], but should also contain anti-mineralizing factors to prevent escalation of the calcification process leading to excessive and uncontrolled mineral deposits[1,2]. When these regulatory mechanisms are inadequate, ectopic mineralization, i.e., inappropriate biomineralization in soft tissues, occurs and causes a spectrum of ectopic calcification disorders (Table 1)[2,4].

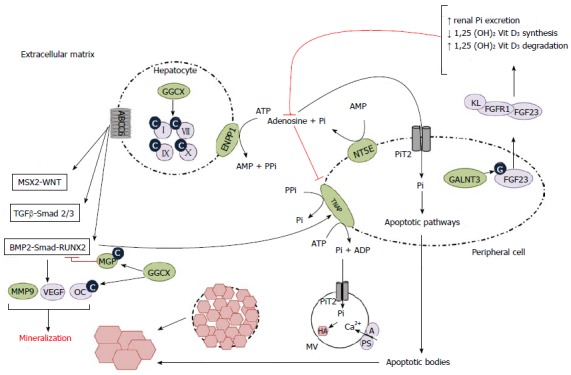

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to ectopic mineralization. Hepatocyte: Impairment of ABCC6 function leads to upregulation of pro-osteogenic pathways (MSX2-WNT, TGFβ-Smad 2/3, BMP2-Smad-RUNX2), upregulation of their downstream targets and eventually to ectopic mineralization. GGCX carboxylates and hence activates multiple targets, such as coagulation factors and MGP, the latter being a potent BMP2-inhibitor and hence mineralization inhibitor. When GGCX function is impaired, these targets stay inactive, leading to increased mineralization. ENPP1 converts ATP to AMP and PPi, the latter being a mineralization inhibitor. Impairment of this conversion and hence a decrease in the PPi level leads to increase in ectopic mineralization. Peripheral cell: After glycosylation by GALNT3, FGF23 forms a complex with FGFR1 and KL (coreceptor) which leads to increased renal excretion of Pi, a pro-mineralizing agent and decreased 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3, causing a decrease in intestinal Pi absorption. NT5E converts AMP to Pi and adenosine, which inhibits the pro-mineralizing TNAP. Impairment of NT5E function leads to increased TNAP activity and decreased PPi concentration, hence leading to ectopic mineralization. Pi is internalized into the peripheral cell by PiT2 and leaves the cell through apoptotic bodies, which cause ectopic mineralization through apoptotic pathways (not shown). In MVs an influx occurs of Pi via PiT2 and of Ca2+, which is facilitated by A and PS. This leads to an accumulation of growing hydroxyapatite crystals, eventually causing the MVs to burst and the crystals to grow in the extracellular matrix. A: Annexin A5; ABCC6: Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette, subfamily C, member 6; ADP: Adenosine diphosphate; AMP: Adenosine monophosphate; ATP: Adenosine triphosphate; BMP2: Bone morphogenetic protein 2; C: Carboxyl; Ca2+: Calcium 2+; ENPP1: Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1; FGF23: Fibroblast growth factor 23; FGFR1: Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1; G: Glycosyl-; GALNT3: UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine: Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 3; GGCX: Gamma-glutamyl carboxylase; HA: Hydroxyapatite; KL: Klotho; MGP: Matrix gla protein; MMP9: Matrix metalloproteinase; MSX2: Muscle segment homeobox, drosophila, homolog of, 2; MV: Matrix vesicle; NT5E: Ecto-5-prime nucleotidase or CD73; OC: Osteocalcine; Pi: Inorganic phosphate; SLC20A2: Solute carrier family 20 (phosphate transporter), member 2; PPi: Inorganic pyrophosphate; PS: Phosphatidyl serine; RUNX2: Runt-related transcription factor; Smad: Mothers against decapentaplegic, drosophila, homolog of; TGFβ: Transforming growth factor β; TNAP: Tissue-non-specific alkaline phosphatase; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; WNT: Wingless-type MMTV integration site family; II, VII, IX, X: Vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors; 1,25 (OH)2 Vit D3: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamine D3 (calcitriol).

Table 1.

Causes of metastatic/dystrophic calcification and ectopic ossification

| Metastatic calcification | Dystrophic calcification | Ectopic ossification | |

| Primary | Primary hyperparathyroidism Pseudo(pseudo)hypoparathyroidism HFTC | PXE PXE-like syndrome GACI Keutel syndrome IBGC ACDC AI | Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva |

| Secondary | Sarcoidosis Vitamin D intoxication Milk-Alkali syndrome Secondary hyperparathyroidism Renal failure Hemodialysis Tumor lysis Therapy with vitamin D and phosphate | Scleroderma Dermatomyositis SLE | Nonhereditary myositis ossificans |

ACDC: Arterial calcification due to CD73 deficiency; AI: Amelogenesis imperfecta; GACI: Generalized arterial calcification of infancy; HFTC: Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis; IBGC: Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification; PXE: Pseudoxanthoma elasticum; SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus.

Uncontrolled mineralization occurs frequently in response to tissue injury or a systemic mineral imbalance. This leads to the development of a calcified lesion, which can occur throughout the body, though tissues as articular cartilage, the cardiovascular (CV) tissues and kidneys seem particularly prone[3,5,6]. Unlike physiological mineralization deposits, which only contain calcium phosphate crystals such as hydroxyapatite, ectopic mineralization depositions may also contain other calcium salts, including calcium oxalates or octacalcium[4].

Regarding the initiation of and pathogenetic mechanisms underlying ectopic mineralization several hypotheses have been proposed (Figure 1): (1) increasing evidence is found that soft tissue calcification can be initiated in matrix vesicles (MVs), extracellular membrane particles (approximately 20-200 nm in diameter), which have a key role in the normal physiological mineralization process[3]. MVs contain calcium-binding non-collagenous matrix proteins, such as secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1; OMIM*166490), which can boost mineralization in vitro[7]. MVs initiate mineralization in 2 phases: (1) initial formation of hydroxyapatite in the MV itself: after budding from the plasma membrane, tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP; OMIM*171760) activity induces an increase of extracellular Pi concentration, which then enters the vesicles via sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate transporters (PiTs). This is followed by calcium influx into the MVs, which is enabled by annexin A5 (ANXA5; OMIM*131230) and phosphatidyl serine (PS), located at the MV inner membrane leaflet[1,3]; and (2) propagation of the calcium salts in the ECM: in the MVs hydroxyapatite crystals continue to grow, eventually rupturing the MV membrane. As a result, the crystals are exposed to the ECM, inducing their further expansion[3,8]; pathological calcification can also be influenced by ectopic osteogenic and chondrogenic signaling, leading to the activation of multiple pro-mineralization proteins[9]. This conversion of tissue-specific cells to bone-like cells has been mainly described in vascular calcification, and is probably due to the common mesenchymal origin of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and bone cells[1]; (3) apoptosis or programmed cell death is accompanied by the release of apoptotic bodies, which exteriorize PS to the outer membrane of the apoptotic body and therefore face the ECM. There, PS may bind calcium, resulting in an accumulation of calcium and phosphate, as is also seen in MVs, thus contributing to physiological and pathological mineralization[1,10]. Another potential apoptosis pathway includes elevated phosphate levels to induce VSMC apoptosis, a process that is possibly caused by downregulation of growth arrest-specific 6 (Gas6; OMIM*600441) and B-cell CLL/Lymphoma (BCL2; OMIM + 151430), with subsequent caspase 3 activation[11,12]; and (4) reactive oxygen species (ROS), highly reactive oxygen-containing molecules, are formed as byproducts of normal oxygen metabolism and has important roles in cell signaling and metabolism. Nonetheless, if ROS concentration surpasses a critical threshold, oxidative stress, accompanied by important cell damage, can occur[13]. Potential sources of ROS in soft tissues are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) (NAD(P)H) oxidase, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), xanthine oxidase, cytochrome P450 and cyclooxygenase; in addition, mitochondrial dysfunction may also lead to the formation of ROS. ROS possibly causes soft tissue mineralization through either the IκB-NF-κB pathway (inhibitor of κB - nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells), upregulation of the pro-osteogenic bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2; OMIM*112261) pathway and/or osteogenic conversion of soft tissue cells[1].

These pathophysiological mechanisms are however not mutually exclusive and display significant crosstalk[1].

Ectopic soft tissue mineralization is a common finding in aging and several common disorders, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and autoimmune diseases, and can be related to significant morbidity and mortality in each of these. It has been shown that vascular calcification correlates with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and that it is an independent risk factor for death in patients with coronary artery calcification[14,15]. However, in these complex, multifactorial disorders, multiple genes are likely to contribute, with each gene having only a small effect[16]. Contrary, in primary genetic mineralization disorders mutations in a single gene or few genes can cause an often extreme and life-threatening phenotype. Though individually rare, as a group they affect a considerable number of patients with important impact on quality of life and high morbidity and mortality rates.

Ectopic mineralization disorders are conventionally classified based on the mechanism through which the mineralization takes place: i.e., metastatic or dystrophic calcification or ectopic ossification (Table 1)[14]: (1) metastatic calcification, due to hyperphosphatemia and/or hypercalcemia; (2) dystrophic calcification, which occurs in diseased (metabolically impaired or dead) tissue under normal calcium and phosphate homeostasis[1]; and (3) ectopic or heterotopic ossification, leading to true bone formation[1,4,17,18].

For many of these disorders, important advances have been made in defining their clinical presentation (phenome), their (molecular) etiology (variome) and the correlation between both. This has led to novel insights and perspectives for the management and treatment of the patients, but also supports the complexity of the pathophysiology of soft tissue mineralization.

This review will focus on the clinical presentation, pathogenesis and management of primary genetic soft tissue mineralization disorders due to dystrophic (Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Generalized arterial calcification of infancy, Keutel syndrome, Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification, Arterial calcification due to CD73 deficiency) or metastatic calcification (Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis).

PSEUDOXANTHOMA ELASTICUM

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE; OMIM#264800) is a rare, autosomal recessive connective tissue disorder, resulting from ectopic mineralization and fragmentation of elastic fibers. The prevalence of PXE is estimated between 1/25000 and 1/100000 with a carrier frequency of 1/80, although this may be an underestimation due to the variability of the phenotype, which in some cases may hinder the diagnosis[19-21].

Clinical characteristics

PXE primarily affects 3 organ systems, i.e., the skin, the eyes and the CV system, albeit with important inter- and intrafamilial variability in severity[19,21,22]. Usually the skin symptoms are the first to arise, though they are not present in all patients, presenting as soft yellowish papules in flexural body areas (i.e., neck, axilla, elbow, groin and knees) (Figure 2A-E)[19]. These solitary papular lesions can coalesce into larger plaques. Loss of resilience may give the skin a wrinkled aspect and can cause an esthetic burden[1,19]. Less frequently, mucosal lesions (usually at the inner lower lip) are present (Figure 2F)[19]. The emergence of additional inelastic skin folds[1], especially in neck (and thigh) area(s) can also cause functional problems, e.g., when sleeping or riding a bicycle[1,19].

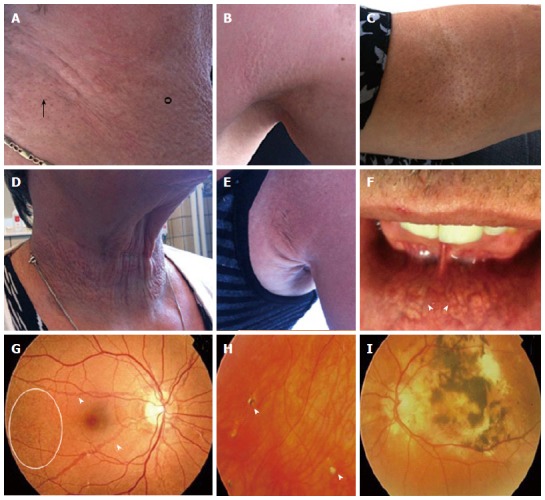

Figure 2.

Dermatological (A-F) and ophthalmological (G-I) manifestations of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. A, B: Flexural areas can show papular lesions (°) and coalesced plaques of papules (arrow); C: Cutaneous peau d’orange; D, E: Additional skin folds; F: Yellowish, reticular pattern on the mucosae of the lip (arrowed); G: Ocular fundi show peau d’orange (circle) and angioid streaks (arrowed); H: Comets and comet tails (arrowhead); I: Choroidal and subretinal hemorrhage.

The most common ocular features in PXE patients are peau d’orange and angioid streaks (AS), which themselves cause no functional impairment (Figure 2G). In later stages choroidal (subretinal) neovascularization (CNV) occurs and these neovessels may rupture, causing retinal hemorrhage (Figure 2I). Symptoms will include metamorphopsia and vision loss, which can be permanent if left untreated. More recently, chorioretinal atrophy, subretinal fluid independent from CNV, pattern dystrophy-like changes, debris accumulation under the retinal pigment epithelium, reticular drusen and a decreased fluorescence on late phase indocyanine green angiography were described[23].

CV symptoms, usually arising when patients are 30-40 years old, include accelerated coronary and peripheral artery disease (hypertension, myocardial infarction, intermittent claudication), diastolic cardiac dysfunction and gastrointestinal hemorrhage[24]. In 15% of PXE patients ischemic stroke may occur, at an average age of 49[1,24]. Heterozygous carriers usually develop neither skin nor eye symptoms but can suffer from accelerated atherosclerosis and (mild) diastolic dysfunction of the heart[24].

To date, no correlation has been established between the PXE phenotype and mutations in the main causal gene adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette, subfamily C, member 6 (ABCC6; OMIM*603234), which complicates the prediction of the evolution and severity of the symptoms in an individual patient[19,25]. The absence of a reliable genotype-phenotype correlation suggests that other genes, so-called modifier genes, may play an important role in influencing the disease course, apart from other factors such as lifestyle, environmental factors and - although less probable - dietary habits[19]. Thus far, only one promising modifier gene, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA; OMIM + 192240) has been identified for the PXE retinopathy[26].

Pathogenesis

PXE is caused by mutations in the ABCC6 gene, encoding an ATP-binding efflux transporter, the substrate and (patho)physiological role of which are yet to be elucidated[27]. The ABCC6 transporter is mainly expressed in the liver and kidneys while only minimally present in the organs affected by PXE[28,29]. This led to the hypothesis that PXE is a metabolic disorder in which a defective transporter causes inefficient transport of one or multiple substrates into the bloodstream[28,29]. As a result, a deficiency of vitamin K (VK) -dependent and -independent mineralization inhibitors occurs, favoring ectopic soft tissue mineralization[23,30,31]. The metabolic hypothesis was reinforced several times, until very recently Ziegler et al[32] reported that a conditional, liver-specific Abcc6-/- mouse model does not develop ectopic mineralization and concluded that mineralization in PXE occurs through a liver-independent mechanism. This would correspond with a second, so-called cellular, hypothesis which states that the local environment in the affected organ systems is altered; in this respect it was shown that PXE fibroblasts suffer mild chronic oxidative stress because of overexpression of oxidative stress-favoring mediators[31,33].

More recently, 3 pro-osteogenic pathways, i.e., BMP2-Smad (mothers against decapentaplegic, drosophila, homolog of; OMIM*601366)- runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2; OMIM*60021) and transforming growth factor β2 (TGFβ2; OMIM*190220)-Smad2/3 pathways and the MSX2 (muscle segment homeobox, drosophila, homolog of, 2; OMIM*123101)-canonical WNT (wingless-type MMTV integration site family; OMIM*164820) pathway which are associated with vascular mineralization, were found to be upregulated in the skin and eyes of PXE knock-out mice and in PXE patients (Figure 1)[34]. The relevance of BMP2-Smad-RUNX2 signaling was alluded on by previous observations in PXE, including the low levels of carboxylated (active) matrix gla protein (MGP; OMIM*154870)/gamma-carboxyglutamic acid, a potent inhibitor of BMP2, the upregulation of several target genes of RUNX2 such as SPP1, osteocalcin, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP9; OMIM*120361), TNAP and VEGFA, the influence of oxidative stress on BMP2 expression and the overexpression of RUNX2 in calcified cardiac tissue of the Abcc6-related dystrophic cardiac calcification mouse[34-36]. Furthermore, apoptosis was identified as an important process in PXE contributing to mineralization, by activation of BCL2 and multiple caspases[34].

Some insights in the dysfunction of pro- and anti-mineralizing factors in the PXE pathogenesis, have been described in the PXE murine model and/or PXE patients. Several local pro-mineralizing factors seem to be upregulated in vitro and/or in vivo (TNAP, BMP2) while mineralization inhibitors, such as ecto-5-prime-nucleotidase or CD73 (NT5E; OMIM*129190), SPP1, ankyrin (mouse, homolog of) (ANKH; OMIM*605145) and VK-dependent calcification inhibitors, were found to be less expressed[37-39].

Besides local factors, systemic inhibitors of mineralization such as Fetuin A and more recently inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi), were shown to be less abundant in PXE. PPi is a potent endogenous inhibitor of vascular calcification, both in vitro and in vivo, which was already shown to be downregulated in PXE fibroblasts, thus promoting pro-calcifying stimuli leading to tissue mineralization[40,41]. Jansen et al[42] found low PPi serum levels in both Abcc6-/- mice and PXE patients, and concluded that an impaired ABCC6 transporter negatively influences PPi efflux from hepatocytes to the hepatic circulation, though the exact mechanism is poorly understood.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PXE is a clinical one to begin with, based on the presence of typical skin and/ or fundus changes. While the skin lesions of PXE can be mimicked macroscopically by other disorders (Table 2), the presence of peau d’orange and/or AS in the ocular fundus can be considered pathognomonic. Diagnostic confirmation can be obtained by skin biopsy, showing shortened, fragmented elastic fibers as well as mineral deposits in the mid-dermis using H&E (hematoxylin and eosin) and von Kossa staining. Molecular analysis of the ABCC6 gene detects both causal mutations in approximately 95% of patients[1,33,43,44]. Sanger sequencing is still the gold standard, but should be complemented with multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, to detect larger deletions and insertions[45]. If no or only one ABCC6 mutation can be identified, it is worthwhile to screen for gamma-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX; OMIM*137167) mutations as digenic inheritance has been described[46]. Furthermore, the initial presentation of the GGCX-related PXE-like disorder with coagulation factor deficiency (see below) can be identical to PXE[47,48]. Sequencing of the ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (ENPP1; OMIM*173335) gene is useful when no ABCC6 mutations can be detected in a patient with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of PXE; digenic inheritance of an ABCC6 and ENPP1 mutation has so far not been reported[49]. This increasing number of genes which may cause PXE as well as the potential importance of modifier genes, brought about a gradual shift from Sanger sequencing towards the more recently introduced next generation sequencing[26,47,50-52].

Table 2.

| Disease | Distinct differences with PXE |

| Beta-thalassemia (PXE phenocopy) | Severe anemia Reduced production of hemoglobin |

| PXE-like syndrome (AR; GGCX gene) | More severe cutaneous phenotype not restricted to flexural areas Vitamin K-dependent coagulation factor deficiency |

| GACI (AR; ENPP1 gene) | Onset in infancy or early childhood Arterial stenosis Early-onset severe myocardial ischemia High mortality rate in early childhood |

| Fibroelastolytic papulosis, Treatment with D-penicillamine | No ophthalmological or CV phenotype |

| Buschke-Ollendorf syndrome (AD; LEMD3 gene) | Skeletal manifestations (osteopoikilosis, stiff joints, osteosclerosis) No ophthalmological or CV phenotype No mineralization |

| Solar elastosis | Dermatological features (lentigines, mottled pigmentation, actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, xerotic texture) No ophthalmological or CV phenotype No mineralization |

| Late-onset focal dermal elastosis | Onset in 7th to 9th life decade No ophthalmological or CV phenotype |

| Cutis laxa | No ophthalmological or CV phenotype Histopathology: scarce and mottled elastic fibers, no mineralization |

| A(R)MD (age-related macular degeneration) | No AS No CV or dermatological phenotype Less unique lesions (outer retinal tabulation or Bruch’s membrane undulation) |

| Presumed ocular histoplasmosis | No AS No CV or dermatological phenotype |

AD: Autosomal dominant; AR: Autosomal recessive; A(R)MD: Age-related macular degeneration; AS: Angioid streaks; CV: Cardiovascular; ENPP1: Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1; GACI: Generalized arterial calcification of infancy; GGCX: Gamma-glutamyl carboxylase; LEMD3: Lem domain-containing protein 3; PXE: Pseudoxanthoma elasticum.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of PXE manifestations is summarized in Table 2.

Management

To date, PXE management is mainly symptomatic, focusing on prevention and treatment of complications[19]. For ophthalmological complications, preventive measures include wearing glasses and avoiding sports and activities with a (relative) high risk of (head) trauma or increased pressure[19,21,60]. Once fundus changes have appeared, an annual control by an ophthalmologist is important, as well as weekly self-examination using the Amsler Grid. If distortion or metamorphopsia occurs, the patient should contact his/her ophthalmologist immediately[20,23]. Timely treatment with anti-VEGF antibodies, such as bevacizumab or ranibizumab, were shown to be successful in forcing back neovessels and preserving visual acuity[1,20,30]. Prophylactic anti-VEGF therapy has however not been proven to be advantageous[19].

The prevention of CV complications consists of controlling traditional CV risk factors (e.g., smoking, obesity, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes)[1]. Upon diagnosis, a baseline screening should be performed with measurement of blood pressure, assessment of biochemical CV risk factors, echocardiography, determination of the ankle-brachial index and duplex ultrasound of the arteries of the neck and lower extremities. If hypertension is found, further assessment with 24-h blood pressure monitoring and an exercise test should be done. Further CV management is tailored based on the results of this screening, usually comprising an annual checkup by a cardiologist and if necessary initiation of secondary prevention[24]. Since heterozygous carriers suffer CV complications more frequently compared to the general population, they should also undergo a baseline CV screening and regular checkups by a cardiologist[24]. Furthermore, the use of anticoagulants, aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided as they may elevate the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding[1]. When complications do occur, standard interventional or surgical procedures can usually be applied[24,61].

For the skin problems no prevention is possible and therapeutic options are scarce. When functional problems arise, mainly due to excessive skin folds, plastic surgery can be attempted[61]. Possible post-surgery complications include slower wound healing and apparition of skin lesions in the scars[61-63]. Recently, Salles et al[64] described a PXE patient in which skin lesions in the neck were successfully treated with fractional carbon dioxide laser therapy. The post-laser reaction - redness, pain, swelling and crusting - was the same as seen in normal skin. After a follow-up of 2 years, the treatment showed an overall satisfactory esthetic result, showing improvement of the skin texture, irregularity, volume and distensibility. Moreover, lipofilling to reduce esthetically disturbing skin folds, especially in the neck region, is being evaluated in an experimental setting[65].

PXE-LIKE SYNDROME WITH MULTIPLE COAGULATION FACTOR DEFICIENCY

In 2007, Vanakker et al[1,47] described a new autosomal recessive disorder which was closely related to PXE and coined it the PXE-like syndrome with multiple coagulation factor deficiency (OMIM#610842). To date, the disorder has been described in 12 patients, 8 of which had molecular confirmation of the clinical suspicion[47,48,66-68].

Clinical characteristics

The initial presentation of the PXE-like syndrome is nearly identical to that of PXE, making it often difficult to distinguish the two diseases in young adults. The natural evolution of the PXE-like disorder is however completely different and characterized by severe cutaneous symptoms with the development of thick and redundant skin folds, not restricted to flexural areas but variably expanding toward limbs and abdomen (Figure 3), a mild retinopathy and a deficiency of the VK-dependent coagulation factors (coagulation factors II, VII, IX, X)[1,47,48]. Furthermore, subclinical atherosclerosis and cerebral aneurysms have been described[47].

Figure 3.

Cutaneous features of a pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like patient with increased amount of generalized thick leathery skin folds.

Pathogenesis

Biallelic mutations have been described in the GGCX gene, encoding a gamma-carboxylase enzyme which performs an essential post-translational modification step of a number of so-called VK-dependent proteins, including clotting factors and mineralization inhibitors (Figure 1). It was shown that the PXE-like mutations result in a reduced activity of the enzyme, thus leading to inadequate carboxylation (or activation) of these VK-dependent proteins. This causes a deficiency of coagulation factors and creates an environment which favors ectopic mineralization[1].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PXE-like syndrome is relatively straightforward when typical skin lesions are seen in combination with a deficiency in the VK-dependent clotting factors. Biochemically, a prolonged prothrombin time can be found, though the coagulation factor deficiency can be very mild[47]. In young individuals, the diagnosis should be considered in every patient suspected of having PXE in whom no ABCC6 mutations are found. Histopathology shows fragmentation and calcification of the mid-dermal elastic fibers, being located in the periphery of the fiber[69]. Light microscopy will not allow differentiating with PXE, but on electron microscopy the elastic fibers are more ragged and the calcification is located in the periphery of the fibers (compared to fiber core mineralization in PXE). The diagnosis can be confirmed by GGCX sequencing[47].

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of PXE-syndrome is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

| Disease | Distinct differences with PXE-like syndrome |

| PXE (AR; ABCC6 gene) | More severe CV and ophthalmological manifestations Skin lesions are less severe and restricted to flexural areas No coagulation factor deficiency associated EM: mineralization in the core of the EF |

| Cutis laxa | No retinopathy No deficiency of coagulation factors Atherosclerosis and cerebral aneurysm are infrequent Histopathology: scarce and mottled elastic fibers, no mineralization |

ABCC6: Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette, subfamily C, member 6; AR: Autosomal recessive; CV: Cardiovascular; EF: Elastic fiber; EM: Electron microscopy; PXE: Pseudoxanthoma elasticum.

Management

The management of PXE-like patients is similar to that of patients with classic PXE. In most, treatment of the coagulation deficiency is not necessary, though the use of anticoagulants is not advised. In rare cases, supplementation with VK may be useful[47].

GENERALIZED ARTERIAL CALCIFICATION OF INFANCY

Generalized arterial calcification of infancy (GACI; OMIM#20800) is an early-onset, autosomal recessive disorder, which has only been described in approximately 100 mostly Caucasian patients[1,70]. The disease typically affects infants of less than 6 mo of age[71,72].

Clinical characteristics

GACI is characterized by arterial stenosis, resulting from myointimal proliferation of muscular arteries, and early-onset severe myocardial ischemia due to extensive deposition of hydroxyapatite in the inner elastic lamina of medium- and large-sized arteries[1,70,73]. Complications include myocardial infarction, hypertension and congestive heart failure, leading to early demise[1]. Other possible manifestations include dermatological and ophthalmological findings typical of PXE, extravascular (mostly periarticular) calcifications, hearing loss and development of hypophosphatemic rickets after infancy[49,70,71,74-77]. The majority of patients die before the age of 1, with the highest fatality rate in the first six months of life, most commonly due to myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, multiple organ failure or persistent arterial hypertension[71,72]. Recently, Rutsch et al[71] reported a mortality rate of 55%, with a marked decrease in the mortality of patients, which survived the first 6 mo. In some of these, spontaneous resolution of the mineralization was seen[78,79].

Pathogenesis

GACI is caused by inactivating mutations in the ENPP1 gene, which encodes ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1. Under normal conditions, ENPP1 is associated with the outer plasma membrane of VSMCs in arteries and generates extracellular PPi through hydrolysis of ATP to adenosine monophosphate (AMP)[2]. PPi is a potent calcification inhibitor, which was already shown to hinder mineral crystal growth by binding to the crystal surface in osteoblast cultures[1,2,17].

Diagnosis

Neonates with GACI can present with rather aspecific symptoms, such as poor feeding and respiratory distress. Consequently the diagnosis is often only established by detecting arterial calcification using plain radiography, ultrasound or computed tomography. Typically, diffuse vascular and periarticular ectopic mineralization is found. GACI should be considered antenatally when ultrasonographic anomalies include arterial calcifications, hydrops, abnormal cardiac contractility and/or hyperechoic kidneys[80]. Confirmation of the diagnosis is possible through molecular analysis of the ENPP1 gene which detects mutations in approximately 70% of cases[49,71,81,82]. When no mutations can be found in ENPP1, ABCC6 sequencing should be performed, due to an overlap in the phenotypes of both diseases[70,73]. An arterial biopsy shows fragmentation in the integral elastic lamina with calcium deposition and fibrointimal hyperplasia causing luminal narrowing, which can occur in places devoid of mineralization[72,83]. Conversely, mineralization can occur without luminal narrowing[84]. Apart from calcium, the depositions also contain iron and mucopolysaccharides[84,85]. The lesions are surrounded by a giant cell reaction[86].

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of GACI is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

| Disease | Distinct differences with GACI |

| PXE (AR; ABCC6) | GACI-like phenotype possible, however infrequent CV phenotype usually less severe No onset in infancy Dermatological and ophthalmological phenotypes more prominent |

| Singleton-Merten Calcification (AD; unknown causal gene) | Dental anomalies (delayed eruption and early loss of permanent teeth, alveolar bone erosion) Osteopenia Acroosteolysis |

| Metastatic calcification due to hypervitaminosis D, hyperparathyroidism or end-stage renal disease | Different distribution of extravascular calcification (renal tubules, bronchial walls and basal mucosa and muscularis mucosae of the stomach) Microscopic vascular changes in media instead of intima |

| Congenital syphilis | Only calcification of the (ascending) aorta Diagnosed mainly in adults Hutchinson teeth, interstitial keratitis, saber tibiae, saddle-shaped nose Histopathology: endarteritis obliterans of vasa vasorum with perivascular plasma cells, lymphocytic cuffing and adventitial fibrosis |

| Iliac artery calcification in healthy infants | Only calcification in the common and internal iliac arteries |

ABCC6: Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette, subfamily C, member 6; AD: Autosomal dominant; AR: Autosomal recessive; CV: Cardiovascular; GACI: Generalized arterial calcification of infancy; PXE: Pseudoxanthoma elasticum.

Management

The treatment options in GACI are limited and rely mostly on the use of bisphosphonates, such as etidronate and pamidronate, which are analogs of PPi. These bisphosphonates possibly act through decreasing bone turnover, inhibiting further growth of mineralized crystals and/or providing an alternative form of PPi that may influence the regulation of mineralization[91]. Vascular calcifications have been reported to disappear under bisphosphonate therapy within a variable time period (2, 5 wk to 2 years). Calcifications do not tend to reappear after cessation of the therapy, although arterial stenosis persists[92,93]. Since prolonged etidronate use in GACI patients has been linked to severe skeletal toxicity, bisphosphonate therapy should be closely monitored and according to some, should be stopped as soon as the calcifications have disappeared[94]. Nevertheless, the prognosis of patients remains poor with only few long-term survivors, the oldest GACI patient being 25[1,71,79,95]. Recently, Towler et al[96] suggested that restoring PPi levels by inhibition of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and/or upregulation of vascular ENPP1 or ANKH-mediated secretion of intracellular PPi may serve as possibilities to limit vascular calcification.

KEUTEL SYNDROME

Since its first identification by Keutel et al[97] in 1971, approximately 30 cases have been described of Keutel syndrome (OMIM#245150), which is an autosomal recessive multisystem disease with an age of onset in childhood (5-15 years)[97,98].

Clinical characteristics

Keutel syndrome is mainly characterized by peripheral pulmonary stenosis, abnormal cartilage ossification or calcification of typically (para)tracheal, bronchial and rib cartilages as well as auricular and nose cartilage[99]. Less frequently soft tissue calcification, i.e., of blood vessels, brain and kidneys, occurs[1]. Other clinical features include CV (ventricular septal defect, pulmonary artery hypoplasia, hypertension) respiratory (recurrent respiratory infections), skeletal (brachytelephalangism, typically sparing the 5th distal phalanx, height below the 25th percentile), neurological symptoms (subnormal intelligence quotient (IQ) in multiple cases) and recurrent otitis media causing inner ear or mixed deafness. Patients have a typical facial gestalt with mild midface hypoplasia, a depressed nasal bridge, small alae nasi and a deep philtrum[100-104]. A long-term follow-up of 4 sisters with Keutel syndrome showed that all clinical manifestations were progressive. Further, these patients developed skin lesions, i.e., multiple erythematous, irregularly bordered macular lesions without induration, typically after the age of 30. Skin biopsy of these lesions failed to show calcification or ossification and loss of elastic fibers was only seen in the papillary dermis[99]. Nevertheless, the prognosis of Keutel syndrome is good in the majority of patients, with life expectancy mainly depending on the severity of the pulmonary complications[99].

Pathogenesis

Keutel syndrome is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the MGP gene, encoding matrix gla protein[1]. MGP is an inhibitor of the pro-osteogenic BMP2-Smad-RUNX2 pathway, by inhibiting BMP2 to bind to its receptor. Consequently, MGP, expressed in chondrocytes, functions as a local mineralization inhibitor under physiological conditions (Figure 1)[105,106]. Impairment of its inhibitory function favors pro-mineralizing signaling, leading to ectopic mineralization[98]. Moreover, Cranenburg et al[107] reported a patient in whom the levels of carboxylated/uncarboxlated MGP were very low, unresponsive to VK supplementation, but in whom high levels of phosphorylated MGP were found. Phosphorylation is a VK-independent posttranslational modification of MGP which may allow binding of calcium crystals in the absence of optimal carboxylation. It was hypothesized that this phosphorylation-dependent residual MGP activity might be sufficient to prevent development of arterial calcification[108].

Diagnosis

The majority of Keutel syndrome patients are diagnosed during childhood based on clinical presentation and radiographic examinations, with abnormal cartilage calcification and brachytelephalangism as major signs. The clinical diagnosis can be confirmed by sequencing of the MGP gene, in which to date 7 loss-of-function mutations have been reported[98,104,109].

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of Keutel syndrome is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

| Disease | Distinct differences with Keutel Syndrome |

| X-linked chondrodysplasia punctata (XL; ARSE gene) | Ichtyosis Cataracts Microcephaly, intellectual disability ASD, VSD, PDA Failure to thrive in infancy Age at diagnosis: usually infancy |

| Warfarin embryopathy | Pectus carinatum Congenital heart defects different from those seen in Keutel syndrome (ASD, PDA, ventriculomegaly) |

| Combined Vitamin K-dependent coagulation factor deficiency | Easy bruising, mucocutaneous bleeding Osteoporosis with normal serum markers |

| Relapsing polychondritis | Age at diagnosis: 40-60 yr Cartilage inflammation, possibly progressing to destruction Aortic or mitral valvular disease Facies: saddle nose deformity, multifocal, tender chondritis, including variably floppy or calcified auricles Cranial neuropathies, hemiplegia |

ARSE: Arylsulfatase E; ASD: Atrial septal defect; PDA: Patent ductus arteriosus; VSD: Ventricular septal defect; XL: X-linked.

Management

No etiologic treatment exists for Keutel syndrome, hence management is merely symptomatic, including (angiographic) dilatation of peripheral artery stenosis and bronchodilating agents for respiratory symptoms (dyspnea and wheezing); the latter however can be inefficient in certain patients[99,108]. Most patients develop hypertension before the age of 20, which can be treated with antihypertensive medication such as perindopril, amlodipine or nifedipine[99].

IDIOPATHIC BASAL GANGLIA CALCIFICATION

Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (IBGC) is a rare neurodegenerative disorder with unknown prevalence. The disease is sometimes referred to as Fahr’s disease, although the the patient Fahr described primarily had mineralization in blood vessels of the white matter of the brain[113]. IBGC affects young to middle aged adults, with an average onset in the 3rd or 4th life decade; however the disease has also been described in childhood[114-116].

Clinical characteristics

IBGC is characterized by bilateral and (almost) symmetrical basal ganglia calcifications (Figure 4)[116]. Ectopic mineralization may also occur in other brain regions, including the nucleus dentatus, thalamus, cerebral cortex and centrum semiovale[116,117]. Neurological symptoms include neuropsychiatric (cognitive impairment, depression, hallucinations, delusions, manic symptoms, anxiety, schizophrenia-like psychosis, personality changes) and movement disorders (a.o. parkinsonism, ataxia due to cerebellar involvement, tremor and paresis), as well as headache, vertigo, stroke-like events, orthostatic hypotension, dysarthria, seizures and papilledema due to raised intracranial pressure[116,118]. Both sporadic and familial IBGC cases have been reported, the latter predominantly with autosomal dominant inheritance[116].

Figure 4.

Transverse computed tomography of the brain displaying symmetrical bilateral ganglia calcification in an idiopathic basal ganglia calcification patient.

Pathogenesis

To date, mutations in 3 genes have been associated with IBGC, i.e., solute carrier family 20 (phosphate transporter), member 2 (SLC20A2; OMIM*158378), the beta polypeptide of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFB; OMIM*190040) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, beta (PDGFRB; OMIM*173410). So far, no genotype-phenotype correlation has been found[119]. The SLC20A2 gene, encoding a Pi transporter (also known as PiT2 which belongs to the type III sodium-dependent phosphate transporter family), is expressed abundantly in a variety of tissues and likely plays a housekeeping role in cellular phosphate uptake (Figure 1)[119,120]. Mutations in the gene have been described in more than 40 IBGC families worldwide and in vitro resulted in impaired Pi transport, leading to accumulation of this pro-mineralizing factor[119,121,122].

More recently, a few IBGC patients were reported harboring mutations in PDGFB or PDGFRB[123-128]. In animal models, Pdgfrb has been identified as an essential mediator in the development of pericytes in brain vessels, which have a key role in the maintenance of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB is hypothesized to be defective in IBGC[123]. Moreover, Villa-Bellosta et al[129] found that the PDGFB-PDGFRB pathway seems to be involved in phosphate-induced calcifications in VSMCs by downregulating SLC20A2. All these data suggest that cerebral phosphate homeostasis plays a role in the development of vascular mineralization[129]. The mineralization generally develops within the vessel wall and in the perivascular space, ultimately extending to the neuron. Upon progression, the calcifications start to compress the vessel lumen, which causes impaired blood flow, starting off a vicious circle with further neural tissue damage and mineral deposition. The mineral depositions tend to vary in composition according to their anatomical site and the proximity to vasculature calcifications, containing components such as calcium phosphate and carbonate; other compounds including glyconate, mucopolysaccharide and metals (iron, copper, magnesium, zinc, aluminum, silver and cobalt) may also be found[116]. Abnormal iron metabolism in IBGC has been described in a single case, showing elevated serum ferritin, reduced levels of serum iron and iron-binding capacity. At autopsy iron depositions were found in the liver, the spleen, the bone marrow and the brain[130]. More recent reports confirm abnormalities in metal metabolism (iron, copper, zinc), although there is no consensus whether the metal levels are elevated (cerebrospinal fluid) or reduced (hair) in IBGC patients[131,132].

Diagnosis

IBGC diagnosis is supported by the following criteria: (1) bilateral calcification of basal ganglia; (2) progressive neurologic dysfunction; (3) absence of biochemical abnormalities; (4) absence of infectious, traumatic or toxic cause; and (5) a significant family history (although sporadic IBGC cases have also been described)[116].

However, the diagnosis can only be established by obtaining a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain, showing bilateral, almost symmetric calcifications of one or more of the affected brain regions, and ruling out other abnormalities (showing bilateral basal ganglia calcifications, and developmental defects)[116,133-136]. Other possible investigations, which are typically normal in IBGC patients, include blood and urine testing for hematologic and biochemical (ALP, serum creatinine, osteocalcin, serum lactic acid at rest and after exercise, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, serum calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, calcitonin, heavy metals and parathyroid hormone (PTH)) parameters and an Ellsworth Howard test (showing a 10-20 fold increase of urinary 3’-5’-cyclic AMP (cAMP) after stimulation with 200 U of PTH)[116,137-139]. Neurological tests are usually normal (electroencephalography, nerve conduction studies, pattern shift visual-evoked potential studies) or show mild abnormalities (brainstem auditory-evoked potentials)[116].

Genetic testing can confirm the IBGC diagnosis. Sequencing of SLC20A2 is the first choice, as well as deletion/duplication analysis if no mutation is found, with a mutation detection rate of 40%. If no mutations are found, PDGFRB and PDGFB sequencing can be performed; the precise mutation detection rate is currently unknown. If no molecular confirmation can be obtained, other (genetic) causes of brain calcification should be considered (Table 6), before establishing a clinical diagnosis of IBGC[116].

Table 6.

| Disease | Distinct differences with IBGC |

| Basal ganglia calcification as incidental finding on CT scans/ aging | In 1% of CT scans Usually benign No clear etiology, especially when in older patients Asymptomatic |

| Hypoparathyroidism | Early onset: childhood/adolescence Hypoparathyroidism, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia Alopecia, dry hair Dental dysplasia, caries Moniliasis Albright osteodystrophy symptoms (short stature, round facies, obesity, short metacarpals/metatarsals) |

| Pseudohypoparathyroidism (AD/maternal imprinting; GNAS, GNASAS1 and STX1A gene) | Early onset: childhood/adolescence Hyperparathyroidism, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia Baseline cAMP in urine low; after Ellsworth Howard test subnormal Intellectual disability Albright osteodystrophy symptoms |

| Pseudo- pseudohypoparathyroidism (AD/paternal imprinting; GNAS gene) | Similar phenotype as pseudohypoparathyroidism Normal serum PTH, calcium and phosphorus Intellectual disability (more obvious than in PHP) |

| Kenny-Caffey syndrome, type 1 (AR; TBCE gene) | Growth delay Cortical thickening of long bones Hypocalcemia, hypoparathyroidism |

| PKAN (AR; PANK2 gene) | Early onset (10% > 10 yr) Pigmentary retinopathy |

| DRPLA (AD; CAG expansion in DRPLA gene) | Phenotype similar to IBGC |

| Neuroferritinopathy (AD; FTL gene) | Dysphagia |

| PLOSL (AR; TYROBP and TREM2 gene) | Radiography: polycystic osseous lesions Frontal lobe syndrome |

| Cockayne syndrome; Aicardi- Goutières syndrome | Onset in infancy/early childhood |

AD: Autosomal dominant; AR: Autosomal recessive; CAG: Cytosine, adenine, guanine; cAMP: 3’-5’-cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CT: Computed tomography; DRPLA: Dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy; FTL: Ferritin light chain; GNAS: GNAS complex locus; GNASAS1: GNAS complex locus, antisense transcript 1; IBGC: Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification; PANK2: Panthothenate kinase 2; PHP: Pseudohypoparathyroidism; PKAN: Panthothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration; PLOSL: Polycystic lipomembranous osteodysplasia with sclerosing leukoencephalopathy); PTH: Parathyroid hormone; STX1A: syntaxin 1A; TBCE: Tubulin-specific chaperone E; TREM2: Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; TYROBP: Tyro protein tyrosine kinase-binding protein.

Differential diagnosis

Symmetrical calcifications of the basal ganglia are not specific to IBGC and a variety of familial and non-familial conditions should be considered. It should be noted that these calcifications can also be incidental findings on CT scan, especially in older individuals (Table 6)[116,140].

Treatment

Since no etiologic treatment is available, management and treatment options focus on symptomatic relief[116,117,120]. Pharmacologic treatment (e.g., anxiolytics and antidepressants) for the psychiatric and movement symptoms can be attempted[117,120]. Possibly, an early causative treatment may reverse the calcification process, causing complete recovery of mental functions, which was already described in hypoparathyroidism, another basal ganglia causing disorder, provided that an intervention target can be identified[116].

ARTERIAL CALCIFICATION DUE TO CD73 DEFICIENCY

Arterial calcification due to CD73 deficiency (ACDC), also referred to as calcifications of joints and arteries, is an autosomal recessive disease, which usually takes an onset in young adulthood[16,144].

Clinical presentation

ACDC is mainly characterized by prominent and often symptomatic calcification of the large arteries of the lower extremities (iliac, femoropopliteal and tibial arteries), typically sparing the coronary circulation[16,144]. Furthermore, periarticular calcifications of (large and smaller) joints of the lower extremities have been described[144]. Typical symptoms include claudication, hemodynamically significant peripheral obstructive artery disease of the lower limbs, joint swelling and pain[144]. The disease seems relatively rare, being only reported in 3 Caucasian families[144,145].

Pathogenesis

To elucidate the molecular etiology of ACDC, genome-wide homozygosity mapping was performed in three families, revealing homozygous and compound heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the NT5E gene[144,145]. NT5E encodes the glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked plasma membrane CD73 ecto-enzyme, which has 5’ ectonucleotidase activity and thus converts AMP to extracellular adenosine and Pi[146]. The enzyme is located on the plasma membrane of vascular cells, supplying adenosine to cell surface receptors[145]. Adenosine is produced immediately downstream of ENPP1 in the extracellular ATP-degradation pathway on the surface of vascular cells, and a lower adenosine level leads to impaired inhibition of TNAP[16,144]. St Hilaire et al[144] hypothesized that increased TNAP activity reduces PPi levels, allowing calcification to occur (Figure 1). Since the vascular calcification in ACDC seems to be limited to the lower extremities, it is likely that members of other ectonucleotidase families, such as ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 or CD39 (ENTPD1; OMIM*601752) and its isoforms or cardiac ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 6 or CD39L2 (ENTPD6; OMIM*603160) (members of the ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (E-NTPDase) family), may compensate NT5E activity in other vascular beds[16,147]. An alternative explanation for this predilection may be the particular distribution of adenosine receptors in these vascular beds[148].

Diagnosis

An ACDC diagnosis can be established based on clinical presentation and a full radiographic workup of the patients, as well as determination of the ankle-brachial index, which should be reduced. Plain radiography can visualize the vessel calcifications; magnetic resonance angiography and especially CT angiography can show diffuse and gross calcification of obstructing lesions. Biochemical indices, including serum electrolytes, cholesterol and vitamin D-levels, PTH, C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor and erythrocyte sedimentation rate should all be normal. The clinical suspicion can be confirmed by NT5E sequencing[144].

Differential diagnosis

Other - often not - hereditary causes of vascular calcification have to be excluded, e.g., diabetes mellitus type 2 and impaired renal function[144]. Since joint swelling and pain was present in all three described families, rheumatologic diseases should also be excluded[144].

Management

Because of the rarity of the disease, no treatment guidelines are available. Bisphosphonates, which were proven to be successful in GACI, possibly by restoring PPi levels, may also be a good treatment option in ACDC[91,144]. Adenosine deficiency could be addressed using dipyridamole, which inhibits its cellular reuptake in vitro and in vivo. Other possible therapeutic options include adenosine receptor agonists or direct TNAP inhibitors (e.g., lansoprazole), all of which need to be further investigated[144].

HYPERPHOSPHATEMIC FAMILIAL TUMORAL CALCINOSIS

Contrary to the disorders described above, autosomal recessive hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis (HFTC; OMIM#211900), is characterized by metastatic mineralization[1,149]. Patients usually show first signs in the first or second decade of life[150].

Clinical characteristics

The most prominent clinical manifestation of HFTC is periarticular mineralization of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, mainly affecting the upper limbs and hip regions, although involvement of other localizations (spine, temporomandibular joints, metacarpals/metatarsals and popliteal space) have also been reported[151]. The calcium salt depositions usually present as firm painful tumorlike masses, which may gradually enlarge over a period of years, causing functional problems including restricted joint mobility[149,151]. Complications of the overlying skin, including pain, infection and ulceration, can cause scarring and deformity[1,149,151]. Other possible manifestations of the disorder are dental abnormalities and retinal AS[152].

Pathogenesis

HFTC can be caused by mutations in UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 3 (GALNT3; OMIM*601756), fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23; OMIM*605380) or klotho (KL; OMIM + 604824), all of which are key regulators of the phosphate metabolism[1]. GALNT3 protects intact FGF23, a phosphaturia-causing protein, from proteolytic processing by O-glycosylation of Threonine residue 178 in a subtilisin-like proprotein convertase (SPC) recognition sequence motif. In this way, FGF23 is activated and enabled to secrete from the cell, while this glycosilation also competitively inhibits proteolytic FGF23 cleavage by proteases. Hence, this glycosylation step is proposed to be a posttranslational regulatory model. In the presence of (nonsense/missense/splice-site) GALNT3 mutations, intact FGF23 is cleaved prior to secretion which leads to an accumulation of fragmented FGF23 and a reduced amount of active FGF23, causing hyperphosphatemia[153,154]. In physiological conditions FGF23 binds to the FGF receptor 1, of which KL, a β-glucuronidase, is an important co-receptor, inducing high affinity interaction between FGF23 and its receptor. This activates the further downstream effects of this pathway, including the maintenance of serum phosphate levels within the normal range by increasing renal phosphate excretion and both a reduction of synthesis rate and acceleration of the degradation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 to reduce intestinal phosphate absorption (Figure 1)[155,156]. Moreover, KL works independently from FGF23 as an enzymatic inhibitor of renal NaPi-2a (sodium/phosphate cotransporter) transporter activity - which requires glucuronidase activity, subsequent proteolytic degradation and possibly internalization of the transporter - eventually leading to reduced renal expression of the transporter[157]. FGF23 fulfills its biological functions in a tissue-specific way, which is likely to be regulated by the limited local distribution of KL[155]. Inactivating mutations in FGF23 as well as missense mutations in KL cause FGF23 deficiency. Consequently renal phosphate reabsorption and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 synthesis is increased, leading to elevated serum concentrations of phosphate, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and calcium and ectopic mineralization[155].

Diagnosis

Next to clinical examination and family history, the diagnosis of HFTC is mainly based on a full radiographic workup: (1) Plain radiographs show the typical appearance of periarticular amorphous, multilobulated and cystic calcifications[158]; (2) CT, showing cystic loculi with fluid-fluid levels caused by calcium layering; (3) MRI imaging, showing lesions of inhomogeneous intensity, help to document the extent and interconnectivity of individual lesions and can help to determine possible surgical approaches; (4) scintigraphy, using a phosphate compound radiolabel (technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate) is helpful in determining the activity level of the disease; and (5) ultrasonography can help to localize fluid collections[149]. A typical feature of HFTC is the absence of erosion/bone destruction by adjacent soft-tissue masses[149]. Biochemically, hyperphosphatemia with normocalcemia, normal or slightly elevated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, hypoparathyroidism and low intact FGF23 proteins levels can be found[152]. A biopsy should be avoided, because of the risk of an infection and should only be done as a last resort. Histopathology shows that mineralization depositions fill up the cystic loculi (active stage), which causes them to become encapsulated by fibrous tissue, eventually ending the mineralization process (relative latent stage)[150].

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of HFTC is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

| Disease | Distinct differences with HFTC |

| Calcinosis universalis | Calcium depositions in tendons and muscle tissues Normophosphatemia High hemosedimentation Microcytic and hypochromic anemia |

| Calcinosis circumscripta | Adult onset Local calcinosis Fingers symmetrically affected |

| Calcific tendinitis | Adult onset Calcification limited to tendons |

| Synovial chondromatosis | Lesions arising from synovial tissue Widespread throughout the body Not all lesions are calcified |

| Osteosarcoma | Long bone malignant tumor 2nd life decade or late adulthood No subcutaneous/skin lesions |

| Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (AD; ACVR1 gene) | Hallux valgus, monophalangism and/or malformed first metatarsal Sporadic episodes of painful soft tissue swellings (flare-ups) in 1st life decade |

| Tophaceous gout | Severe form of gout Severe joint deformity, chronic pain and functional decline More prominent in Asian population (slow metabolizers) and in young men with strong genetic predisposition |

| Calcific myonecrosis | Post-traumatic (time interval of several years possible) Lower limbs only |

| NFTC (AR; SAMD9 gene) | Reddish-to-hyperpigmented skin lesions during the first year of life (preceding calcified nodules) Severe conjunctivitis and gingivitis Normophosphatemia |

| Secondary tumoral calcinosis | Renal insufficiency, hyperparathyroidism, or hypervitaminosis D |

| Rheumatological diseases | Usually normophosphatemia and - calcemia Possibly positive results in antinuclear, anti-Smith, anti-centromere and anti-scleroderma antibodies, which should all be negative |

ACVR1: Activin A receptor, type 1; AD: Autosomal dominant; AR: autosomal recessive; HFTC: Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis; NFTC: Normophosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis; SAMD9: Sterile alpha motif domain-containing protein 9.

Management

HFTC should be treated according to the location, size of the lesion and its relations to its environment. A first treatment option is medically reducing hyperphosphatemia through phosphate depletion, by dietary phosphorus restriction and/or the administration of phosphate binding chelating agents such as aluminum hydroxide. This method has a variable success rate, both in normo- and hyperphosphatemic cases. When combined with acetazolamide, which induces phosphaturia, a synergistic effect occurs, especially in the hyperphosphatemic form of familial tumoral calcinosis[149].

A second treatment option is early surgical resection of the lesions; however a considerable recurrence rate of the lesions, which have the tendency of growing faster, poses a major problem. Therefore it is very important that resections contain the lesion, and preferably should contain a wider perilesional area/band, including the hypervascular region beyond the periphery of the lesion. Broad resections can cause problems in case of voluminous lesions, which may require extensive reconstructive surgery[149]. Surgery is indicated when lesions are painful, recurrently infected, ulcerated or when functional impairment occurs[149]. Surgical complications include: (1) prolonged drainage of the wound, possibly leading to delayed wound healing and sinus tract formation; (2) secondary infections due to chronic wound problems, especially when the disease is extensive or when resection is incomplete; and (3) recurrence, which is more frequently seen after incomplete resection[167].

During the active stage of the disease, primary medical treatment of HFTC is justified and may even be recommended, because the postresection recurrence rate of lesions is even higher in this stage. In the relative latent stage, encapsulation occurs which hinders ion exchange, thus making surgery more advantageous[149]. Alternative treatment options, including steroids, bisphosphonates, calcitonin and radiotherapy, have not been proven to be effective[149].

CONCLUSION

Ectopic mineralization disorders comprise a wide range of heterogeneous diseases, which can affect a variety of tissues, causing important health problems. Insights in the mechanisms that cause these diseases have led to the observation that many - if not all - are closely related to one another from a mechanistic point of view. The considerable differences in clinical presentation and natural course however suggest that our current knowledge is merely the proverbial tip of the iceberg and that the subtle mechanisms which render each disease to be unique are still largely to be uncovered. Nevertheless, the pathophysiological knowledge to date has already led to several successful treatment options and a number of promising targets for the future. As such, ectopic mineralization diseases are a fine example for the interaction between the variome and the phenome.

Footnotes

Supported by The Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) (FWO14/ASP/084), Vanakker OM is a senior clinical investigator at the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders; Contract grant sponsor: FWO grant No G.0241.11N and Methusalem grant No. 08/01M01108.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: November 29, 2014

First decision: February 7, 2015

Article in press: May 18, 2015

P- Reviewer: Anis S, Shipman A S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Vanakker O, Hosen MJ, De Paepe A. Ectopic soft tissue calcification: process, determinants and health impact. Hauppauge, NY: Human Anatomy and Physiology; 2013. pp. 261–304. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirsch T. Biomineralization--an active or passive process? Connect Tissue Res. 2012;53:438–445. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2012.730081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golub EE. Biomineralization and matrix vesicles in biology and pathology. Semin Immunopathol. 2011;33:409–417. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0230-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giachelli CM. Ectopic calcification: gathering hard facts about soft tissue mineralization. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:671–675. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65313-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kornak U. Animal models with pathological mineralization phenotypes. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirsch T. Determinants of pathological mineralization. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:174–180. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000209431.59226.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahar NN, Missana LR, Garimella R, Tague SE, Anderson HC. Matrix vesicles are carriers of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and noncollagenous matrix proteins. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26:514–519. doi: 10.1007/s00774-008-0859-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean DD, Schwartz ZV, Muniz OE, Gomez R, Swain LD, Howell DS, Boyan BD. Matrix vesicles contain metalloproteinases that degrade proteoglycans. Bone Miner. 1992;17:172–176. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(92)90731-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanahan CM, Crouthamel MH, Kapustin A, Giachelli CM. Arterial calcification in chronic kidney disease: key roles for calcium and phosphate. Circ Res. 2011;109:697–711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.234914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scull CM, Tabas I. Mechanisms of ER stress-induced apoptosis in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2792–2797. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.224881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Son BK, Kozaki K, Iijima K, Eto M, Nakano T, Akishita M, Ouchi Y. Gas6/Axl-PI3K/Akt pathway plays a central role in the effect of statins on inorganic phosphate-induced calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;556:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collett G, Wood A, Alexander MY, Varnum BC, Boot-Handford RP, Ohanian V, Ohanian J, Fridell YW, Canfield AE. Receptor tyrosine kinase Axl modulates the osteogenic differentiation of pericytes. Circ Res. 2003;92:1123–1129. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000074881.56564.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, Giordano S, Zhang J. Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signalling. Biochem J. 2012;441:523–540. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Q, Uitto J. Mineralization/anti-mineralization networks in the skin and vascular connective tissues. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nitschke Y, Rutsch F. Genetics in arterial calcification: lessons learned from rare diseases. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2012;22:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutsch F, Nitschke Y, Terkeltaub R. Genetics in arterial calcification: pieces of a puzzle and cogs in a wheel. Circ Res. 2011;109:578–592. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Jiang Q, Uitto J. Ectopic mineralization disorders of the extracellular matrix of connective tissue: molecular genetics and pathomechanisms of aberrant calcification. Matrix Biol. 2014;33:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards DS, Clasper JC. Heterotopic ossification: a systematic review. J R Army Med Corps. 2014:Jul 11; Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2014-000277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finger RP, Charbel Issa P, Ladewig MS, Götting C, Szliska C, Scholl HP, Holz FG. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: genetics, clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:272–285. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgalas I, Tservakis I, Papaconstaninou D, Kardara M, Koutsandrea C, Ladas I. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, ocular manifestations, complications and treatment. Clin Exp Optom. 2011;94:169–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2010.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu X, Plomp AS, van Soest S, Wijnholds J, de Jong PT, Bergen AA. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a clinical, histopathological, and molecular update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:424–438. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(03)00053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christen-Zäch S, Huber M, Struk B, Lindpaintner K, Munier F, Panizzon RG, Hohl D. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: evaluation of diagnostic criteria based on molecular data. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:89–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gliem M, Zaeytijd JD, Finger RP, Holz FG, Leroy BP, Charbel Issa P. An update on the ocular phenotype in patients with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Front Genet. 2013;4:14. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campens L, Vanakker OM, Trachet B, Segers P, Leroy BP, De Zaeytijd J, Voet D, De Paepe A, De Backer T, De Backer J. Characterization of cardiovascular involvement in pseudoxanthoma elasticum families. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2646–2652. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanakker OM, Hosen MJ, Paepe AD. The ABCC6 transporter: what lessons can be learnt from other ATP-binding cassette transporters? Front Genet. 2013;4:203. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zarbock R, Hendig D, Szliska C, Kleesiek K, Götting C. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms as prognostic markers for ocular manifestations in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3344–3351. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szabó Z, Váradi A, Li Q, Uitto J. ABCC6 does not transport adenosine - relevance to pathomechanism of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104:421; author reply 422. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Saux O, Urban Z, Tschuch C, Csiszar K, Bacchelli B, Quaglino D, Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Pope FM, Richards A, Terry S, et al. Mutations in a gene encoding an ABC transporter cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:223–227. doi: 10.1038/76102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lefthériotis G, Omarjee L, Le Saux O, Henrion D, Abraham P, Prunier F, Willoteaux S, Martin L. The vascular phenotype in Pseudoxanthoma elasticum and related disorders: contribution of a genetic disease to the understanding of vascular calcification. Front Genet. 2013;4:4. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q, Jiang Q, Pfendner E, Váradi A, Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical phenotypes, molecular genetics and putative pathomechanisms. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchione R, Kim N, Kirsner RS. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: new insights. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:258. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziegler SG, Ferreira CR, Pinkerton , AB , Millan JL, Gahl WA, Dietz HC. Novel insights regarding the pathogenesis and treatment of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (2014) Available from: http://www.ashg.org/2014meeting/abstracts/fulltext/f140120885.htm.

- 33.Hosen MJ, Lamoen A, De Paepe A, Vanakker OM. Histopathology of pseudoxanthoma elasticum and related disorders: histological hallmarks and diagnostic clues. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012;2012:598262. doi: 10.6064/2012/598262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosen MJ, Coucke PJ, Le Saux O, De Paepe A, Vanakker OM. Perturbation of specific pro-mineralizing signalling pathways in human and murine pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:66. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sowa AK, Kaiser FJ, Eckhold J, Kessler T, Aherrahrou R, Wrobel S, Kaczmarek PM, Doehring L, Schunkert H, Erdmann J, et al. Functional interaction of osteogenic transcription factors Runx2 and Vdr in transcriptional regulation of Opn during soft tissue calcification. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuzaj P, Kuhn J, Michalek RD, Karoly ED, Faust I, Dabisch-Ruthe M, Knabbe C, Hendig D. Large-scaled metabolic profiling of human dermal fibroblasts derived from pseudoxanthoma elasticum patients and healthy controls. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanakker OM, Martin L, Schurgers LJ, Quaglino D, Costrop L, Vermeer C, Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Coucke PJ, De Paepe A. Low serum vitamin K in PXE results in defective carboxylation of mineralization inhibitors similar to the GGCX mutations in the PXE-like syndrome. Lab Invest. 2010;90:895–905. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miglionico R, Armentano MF, Carmosino M, Salvia AM, Cuviello F, Bisaccia F, Ostuni A. Dysregulation of gene expression in ABCC6 knockdown HepG2 cells. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2014;19:517–526. doi: 10.2478/s11658-014-0208-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bacchelli B, Quaglino D, Gheduzzi D, Taparelli F, Boraldi F, Trolli B, Le Saux O, Boyd CD, Ronchetti IP. Identification of heterozygote carriers in families with a recessive form of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) Mod Pathol. 1999;12:1112–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson K, Jung A, Murphy A, Andreyev A, Dykens J, Terkeltaub R. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is a downstream regulator of nitric oxide effects on chondrocyte matrix synthesis and mineralization. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1560–1570. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200007)43:7<1560::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boraldi F, Annovi G, Bartolomeo A, Quaglino D. Fibroblasts from patients affected by Pseudoxanthoma elasticum exhibit an altered PPi metabolism and are more responsive to pro-calcifying stimuli. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jansen RS, Duijst S, Mahakena S, Sommer D, Szeri F, Váradi A, Plomp A, Bergen AA, Oude Elferink RP, Borst P, et al. ABCC6-mediated ATP secretion by the liver is the main source of the mineralization inhibitor inorganic pyrophosphate in the systemic circulation-brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1985–1989. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuo FS, Berbert AL, Mantese SA, Loyola AM, Cardoso SV, de Faria PR. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum of the skin with involvement of the oral cavity. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:490785. doi: 10.1155/2013/490785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lebwohl M, Neldner K, Pope FM, De Paepe A, Christiano AM, Boyd CD, Uitto J, McKusick VA. Classification of pseudoxanthoma elasticum: report of a consensus conference. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81894-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costrop LM, Vanakker OO, Van Laer L, Le Saux O, Martin L, Chassaing N, Guerra D, Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Coucke PJ, De Paepe A. Novel deletions causing pseudoxanthoma elasticum underscore the genomic instability of the ABCC6 region. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:112–117. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Q, Grange DK, Armstrong NL, Whelan AJ, Hurley MY, Rishavy MA, Hallgren KW, Berkner KL, Schurgers LJ, Jiang Q, et al. Mutations in the GGCX and ABCC6 genes in a family with pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:553–563. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vanakker OM, Martin L, Gheduzzi D, Leroy BP, Loeys BL, Guerci VI, Matthys D, Terry SF, Coucke PJ, Pasquali-Ronchetti I, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like phenotype with cutis laxa and multiple coagulation factor deficiency represents a separate genetic entity. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:581–587. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]