Abstract

Acute administration of the stress hormone corticosterone enhances memory consolidation in a manner that is dependent upon the modulatory effects of the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA). Posttraining administration of corticosterone increases expression of the activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein (Arc) in hippocampal synaptic-enriched fractions. Interference with hippocampal Arc expression impairs memory, suggesting that the corticosterone-induced increase in hippocampal Arc plays a role in the memory enhancing effect of the hormone. Blockade of β-adrenoceptors in the BLA attenuates the corticosterone-induced increase in hippocampal Arc expression and blocks corticosterone-induced memory enhancement. To determine whether posttraining corticosterone treatment affects Arc protein expression in synapses of other areas of the brain that are involved in memory processing, a memory-enhancing dose of corticosterone was administered to rats immediately after inhibitory avoidance training. As seen in the hippocampus, Arc protein expression was increased in synaptic fractions taken from the prelimbic region of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Blockade of Arc protein expression significantly impaired memory, indicating that the protein is necessary in the mPFC for long-term memory formation. To test the hypothesis that blockade of β-adrenoceptors in the BLA would block the effect of systemic corticosterone on memory and attenuate mPFC Arc expression, as it does in the hippocampus, posttraining intra-BLA microinfusions of the β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol were given concurrently with the systemic corticosterone injection. Although this treatment blocked corticosterone-induced memory enhancement, it increased corticosterone-induced Arc protein expression in mPFC synaptic fractions. These findings suggest that the BLA mediates stress hormone effects on memory by participating in the negative or positive regulation of corticosterone-induced synaptic plasticity in efferent brain regions.

Keywords: BLA, Cortisol, Avoidance learning, Norepinephrine, Stress, Immediate early gene, Memory consolidation, Synaptic plasticity

1. Introduction

Adrenal stress hormones modulate memory consolidation in human and non-human animals (Cahill, Prins, Weber, & McGaugh, 1994; de Quervain, Aerni, Schelling, & Roozendaal, 2009; Gold, van Buskirk, & McGaugh, 1975). Extensive evidence indicates that the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA) plays a critical role in this hormonal regulation of memory (McGaugh, 2004). For example, glucocorticoids interact with the noradrenergic system in the amygdala to enhance memories for emotionally arousing events in both humans and rats (Roozendaal, Barsegyan, & Lee, 2008; van Stegeren et al., 2007). In rodents, memory-enhancing corticosterone treatment increases norepinephrine levels in the amygdala (McReynolds et al., 2010). Studies performed in humans and rodents demonstrate that the amygdala interacts with multiple efferent brain regions, such as the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), during the memory consolidation period and this interaction is correlated with memory performance (Dolcos, LaBar, & Cabeza, 2004; Hayes et al., 2010; Murty, Ritchey, Adcock, & LaBar, 2010) for review see (McGaugh, 2004). A potential mechanism of BLA modulation of memory consolidation is through an influence on synaptic plasticity (Ikegaya, Saito, & Abe, 1994) and expression of plasticity-related proteins (Holloway-Erickson, McReynolds, & McIntyre, 2012; McIntyre et al., 2005) in efferent brain regions.

The protein product of the activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated immediate early gene (Arc/Arg 3.1) is necessary for maintenance of hippocampal LTP and long-term memory of an aversive task (Guzowski et al., 2000; Holloway & McIntyre, 2011; McIntyre et al., 2005; Ploski et al., 2008). Our findings indicate that the BLA influences Arc protein expression in efferent brain regions. Posttraining intra-BLA infusions of the β-adrenergic agonist clenbuterol enhance memory and increase Arc protein expression in the hippocampus in a post-transcriptional manner (McIntyre et al., 2005). Arc mRNA is found in the stimulated regions of dendrites and can undergo local protein translation in vitro, suggesting regulation of Arc expression may occur at the synapse (Steward, Wallace, Lyford, & Worley, 1998; Yin, Edelman, & Vanderklish, 2002). Indeed, Arc protein expression is increased in dorsal hippocampal synapses when training on an aversive memory task is followed by memory-enhancing systemic injections of the stress hormone corticosterone. Antagonism of β-adrenoceptors in the BLA blocks corticosterone-induced enhancement of memory consolidation and attenuates the increase in hippocampal synaptic Arc protein expression (McReynolds et al., 2010). It is not yet determined that the role of the BLA as a mediator of stress hormone modulation of synaptic protein expression is conserved across brain regions.

The mPFC has a high density of glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) and has substantial anatomical connections with the BLA (McDonald, 1991; Meaney & Aitken, 1985; Reul & de Kloet, 1985). The prelimbic region of the mPFC is critically involved in the expression of conditioned fear and consolidation of aversive memories (Barsegyan, Mackenzie, Kurose, McGaugh, & Roozendaal, 2010; Corcoran & Quirk, 2007). Infusions of a GR agonist into either the BLA or the mPFC enhance the consolidation of long-term memory whereas inhibiting the MAPK cascade in either region prevents the memory-enhancing effect of a GR agonist infused into the other. This suggests that the mPFC and BLA must function as a circuit to modulate memory consolidation (Roozendaal et al., 2009).

If the role of the BLA as a mediator of stress hormone modulation of synaptic protein expression is conserved across brain regions, memory-enhancing glucocorticoids should exert their effects through noradrenergic actions in the BLA which, in turn, increase synaptic plasticity-associated proteins such as Arc in regions of the brain that support long-term memory. According to evidence that the prelimbic (PL) region of the mPFC is critically involved in the consolidation of conditioned fear and aversive memory, memory-enhancing corticosteroid administration should increase expression of Arc protein in synapses of the PL and inactivation of the noradrenergic system within the BLA should attenuate that Arc effect. The present study examined the effect of posttraining administration of corticosterone on memory and synaptic Arc protein expression in synaptoneurosomes taken from the rat mPFC. In order to determine whether Arc protein expression in the mPFC was a critical component of memory consolidation, Arc translation to protein was blocked with intra-mPFC microinfusions of Arc antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. Finally, to test the hypothesis that BLA norepinephrine interacts with corticosterone-induced Arc protein expression in the mPFC, intra-BLA infusions of the β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol were administered immediately following training and administration of corticosterone. In order to target the consolidation phase of memory processing while avoiding performance effects, all interventions were given immediately after training.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Two hundred and two male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–275 g upon arrival), purchased from Charles River Breeding Laboratories, were housed individually in a temperature-controlled (22 °C) colony room, with food and water available ad libitum. Animals were maintained on a 12 h light–12 h dark cycle (7:00–19:00 h, lights on) and kept in the animal colony for one week before commencement of surgical or behavioral procedures. All experimental procedures were in compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (University of Texas at Dallas).

2.2. Surgery

For implantation of infusion guide cannulae, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (1% in O2) (Western Medical Supply) and the skull was positioned in a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting Inc). For animals used in the intra-BLA infusion experiment, two 15-mm-long guide cannulae (23 gauge; Small Parts) were implanted bilaterally with the tips 2 mm above the BLA [coordinates: anteroposterior (AP), −2.7 mm from Bregma; mediolateral (ML), ±5.2 mm from midline; dorsoventral (DV), −6.4 mm below skull surface; incisor bar, −3.3 mm from interaural line (Paxinos & Watson, 2005)]. The guide cannulae were fixed in place with acrylic dental cement and two small anchoring screws. Stylets (15-mm long insect dissection pins) were inserted into each cannula to maintain patency. For animals used in the intra-mPFC infusion experiment, two 12-mm-long guide cannulae (23 gauge; Small Parts) were implanted bilaterally with the tips 1.5 mm above the prelimbic region of the mPFC (AP, +3.6 mm; ML, ±0.5 mm; DV, −2.5 mm). The guide cannulae were fixed in place with acrylic dental cement and two small anchoring screws. Stylets (12-mm long insect dissection pins) were inserted into each cannula to maintain patency. After surgery, rats were given 2.0 mL of saline to facilitate clearance of the drugs. Rats were allowed to recover for a minimum of 7 days before training.

2.3. Inhibitory avoidance

In order to habituate rats to the experimental procedures, they were handled for 2 min per day, five consecutive days before training. They were then trained on an inhibitory avoidance task. The inhibitory avoidance apparatus consisted of a trough-shaped alley (91 cm long, 15 cm deep, 20 cm wide at the top and 6.4 cm wide at the floor) that was divided into two compartments, separated by a manually controlled sliding door that opened by retracting into the floor. The starting compartment (31 cm long) was white and illuminated, whereas the shock compartment (60 cm long) was made of two dark electrifiable metal plates and was not illuminated. The rats were placed in the light “safe” compartment and allowed to cross to the dark “shock” compartment. After a rat stepped completely into the dark compartment, the sliding door was closed and a single inescapable footshock (0.32 mA, 1 s) was delivered. This footshock value was chosen because it does not increase norepinephrine levels in the BLA. However, a significant elevation of norepinephrine and memory enhancement were observed when IA training with a 0.32 mA footshock was paired with an immediate posttraining systemic injection of corticosterone (3 mg/kg, i.p.; McReynolds et al., 2010). For rats that were used in the intra-BLA infusion experiment, the footshock value was 0.38 mA for 1 s. For rats that were used in the intra-mPFC infusion experiment, the footshock value was 0.45 mA for 1 s to ensure that the control animals showed sufficient memory. Rats were removed from the dark compartment 15 s after footshock administration and, after drug treatment, returned to the home cage. Some rats were given a retention test 48 h after training. During the retention test, rats were returned to the light compartment of the inhibitory avoidance apparatus and the latency to reenter the dark compartment with all four paws (maximum latency 600 s) was measured. Memory of the training experience was inferred from longer crossing latencies on the retention test. No shock or drug was delivered during retention testing. Other animals were sacrificed 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, 1 h, 3 h, or 6 h after training and drug treatment, and brains were used for analysis of Arc protein expression.

2.4. Drug treatment

The adrenocortical hormone corticosterone (3 mg/kg, i.p.; Sigma–Aldrich) or vehicle was injected immediately after inhibitory avoidance training. Corticosterone was first dissolved in 100% ethanol and then diluted in 0.9% saline to reach its final concentration. The final concentration of ethanol was 5%. The vehicle solution contained 5% ethanol in saline only. This dose of corticosterone was chosen based on previous experiments showing a significant enhancing effect on memory (de Quervain, Roozendaal, & McGaugh, 1998; Hui et al., 2004; McReynolds et al., 2010; Roozendaal, Okuda, Van der Zee, & McGaugh, 2006).

In some rats, the β-adrenoceptor antagonist DL-propranolol (0.5 μg per 0.2 μL; Sigma–Aldrich) or vehicle was infused into the BLA after training and corticosterone injection. Propranolol was dissolved in a vehicle of 0.9% saline. The infusion needles were 30-gauge microinfusion needles that were attached to 10-μL Hamilton microsyringes by polyethylene tubing (PE-20). The drug solution was backfilled into the needle and the infusion was driven by a minipump (Harvard Instruments). The injection needle protruded 2.0 mm beyond the cannula tip and a 0.2-μL injection volume was infused over the course of 32 s. The needles were left in place for an additional 30 s to allow for diffusion. For rats receiving a retention test, propranolol or vehicle was infused bilaterally into the BLA. For rats that were used for Arc protein expression analysis, propranolol or vehicle was infused unilaterally into either the left or right BLA (and vehicle always in the other hemisphere; Fig. 7) or vehicle was infused bilaterally. Drug and vehicle infusions were counterbalanced across hemispheres in a randomized fashion.

Fig. 7.

Intra-basolateral amygdala infusions of propranolol or vehicle. (A) For rats receiving a memory test, bilateral vehicle or propranolol was infused into the BLA. (B) Representative image of cannula track and needle placement within the BLA. (C) For rats used for analysis of Arc protein expression, vehicle was infused into the BLA of one hemisphere and propranolol was infused into the BLA of the opposite hemisphere. The location of the drug infusion was counter-balanced. For the control group, vehicle was infused bilaterally into the BLA. (D) Injection needle tips of all rats included in the intra-BLA experiment. Black circles represent rats that were used for the behavioral experiment and gray circles represent rats that were used for analysis of Arc protein expression. Adapted from Paxinos and Watson (2005).

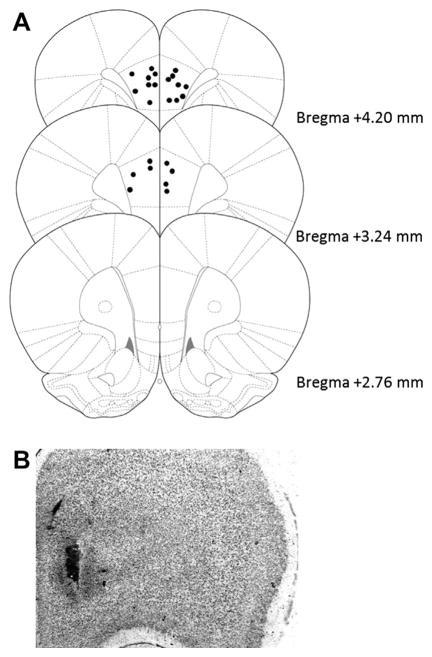

2.5. Tissue preparation

Rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane (Western Medical Supply) 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, or 1 h after training and drug treatment and brains were rapidly removed and flash frozen by submersion for 2 min in a beaker filled with 2-methylbutane sitting in a dry-ice ethanol bath. Cage control animals that were not trained were processed identically. The brains from rats that received intra-BLA infusions were cut horizontally just above the rhinal fissure and several 40-μm thick sections were taken with a Cryostat, mounted on glass slides and stained with thionin. For the intra-mPFC infusion experiment, several 40-μm thick sections were taken at the level of the mPFC with a Cryostat, mounted on glass slides and stained with thionin. Brain sections were analyzed under a light microscope to identify needle placement and the location of infusion. Only brains with needle tracks terminating in the BLA or prelimbic region of the mPFC were used for analysis (Figs. 4, 6 and 7). For Arc comparisons, a Cryostat was used to make 3 500-μm-thick coronal sections from frozen brain tissue at the level of the medial prefrontal cortex (+4.2 mm to +2.5 mm from Bregma) and tissue punches were taken from the prelimbic region of the prefrontal cortex using a tissue punch kit (1.00 mm in diameter), and pooled into one sample for each hemisphere/rat. The tissue punches were stored at −80 °C for later Western blot analysis.

Fig. 4.

Intra-medial prefrontal cortex infusions of Arc scrambled or antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. (A) Injection needle tips of all rats included in the intra-mPFC experiment. Adapted from Paxinos and Watson (2005). (B) Representative image of cannula track and needle placement within the mPFC.

Fig. 6.

Intra-medial prefrontal cortex infusions of Arc antisense oligodeoxynucleotides reduces Arc protein expression. The spread of the infusion was analyzed using a biotinylated ODN which was visualized using a nickel ABC-DAB reaction kit. (A) The spread of the infusion was greatest at 1 h. The spread of the infusion is outlined in the figure of the mPFC. Light grey represents the smallest spread of the infusion at 1 h after the infusion. Dark grey represents the largest spread of the infusion at 1 h after the infusion. The injection needle tips are represented by black circles. Adapted from Paxinos and Watson (2005). (B) Light grey represents the smallest spread of the infusion at 3 h after the infusion. Dark grey represents the largest spread of the infusion at 3 h after the infusion. (C) Light grey represents the smallest spread of the infusion at 6 h after the infusion. Dark grey represents the largest spread of the infusion at 6 h after the infusion. (D) Representative western blot images from the quantification of Arc protein reduction. Arc is the top band and actin is the bottom band. At 1 h after the infusion, Arc protein was reduced by 14.21% in the hemisphere that received the antisense ODN. At 3 h after the infusion, Arc protein was reduced 43.68% in the hemisphere that received the antisense ODN. At 6 h after the infusion, Arc protein was reduced by 52.64% in the hemisphere that received the antisense ODN. (E) In order to quantify Arc protein reduction as a result on intra-mPFC infusions of Arc antisense ODN, the antisense ODN was infused into the mPFC of one hemisphere and the scrambled ODN was infused into the mPFC of the other hemisphere. SCR = scrambled, AS = antisense.

2.6. Synaptoneurosome preparation

The tissue punches from one hemisphere were homogenized with a nylon pestle, 16 strokes, in 70 μL homogenization buffer solution [in mM: NaCl, 124; KCl, 5; CaCl2·2 H2O, 0.1; MgCl2·6 H2O, 3.2; NaHCO3, 26; glucose, 10; pH 7.4, containing 20% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich), and 10% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail II (Sigma–Aldrich)]. After homogenization, the total volume was brought to 500 μL with the homogenization buffer. The homogenate was backfilled into a 1 ml syringe then filtered through 3 layers of nylon mesh with a pore size of 100 μm (Small Parts) positioned inside a 13 mm syringe filter holder (Pall Life Sciences). The filtered solution was backfilled again into a 1 ml syringe and filtered through a 0.9-μm pore nitrocellulose filter (Sigma–Aldrich) inside a 13 mm syringe filter holder. The final filtered solution was centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was resuspended in 50 μL cold resuspension buffer [in mM: Tris base, 65.2; NaCl, 150.0; EDTA, 2.0 mM; NaH2PO4, 50.0; Na4P2O7, 10.0 mM, pH 7.4 containing 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Sodium deoxycholate, 20% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich) and 10% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail II (Sigma–Aldrich)].

2.7. Protein assay and immunoblotting

Total protein concentrations from synaptoneurosome tissue were determined using a Qubit fluorometer and Qubit protein assay kit (Invitrogen). After purification, those synaptoneurosome samples containing 15 μg or more of total protein were heated in a sample buffer with a reducing agent (Invitrogen), loaded, and then run on 8% Bis-Tris MIDI gels (Invitrogen). Tissue from each condition was loaded into adjacent wells in each gel. The proteins were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using an iBlot dry-blotting system (Invitrogen). Membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS: 150 mM NaCl/100 mM Tris base, pH 7.5) and incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution (5% Carnation nonfat dry milk in TBS-Tween) overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies were anti-Arc (rabbit polyclonal; 1:3000, Synaptic Systems) and anti-actin (rabbit; 1:2000, Sigma–Aldrich). On the next day, the membranes were incubated with a secondary HRP-linked antibody (goat anti-rabbit; 1:6000, Millipore) for 1 h. Immunoreactivity was detected using chemiluminescence (ECL Western Blot Kit; Pierce). Invitrogen markers were run on all gels to determine the relative mobility of the immunoreactive bands. For densitometric quantification of these results, the films were scanned and converted into TIF files for analysis with NIH Image J software.

2.8. Oligodeoxynucleotides

The oligodeoxynulceotides (ODNs) that were used had an encoded sequence for Arc mRNA near the translation start site. The ODNs were chimeric phosphorothioate/phosphodiester ODNs as previous studies indicate that these ODNs retain biochemical specificity, are more stable than unmodified phosphodiester ODNs, and less toxic than full phosphorothioate ODNs (Hooper, Chiasson, & Robertson, 1994; Widnell et al., 1996). Either Arc antisense or scrambled control oligodeoxynucleotides (Antisense: GTCCAGCTCCATCTGCTCGC; Scrambled: CGTGCACCTCTCGCAGCTTC; Midland Certified Reagant Company) were delivered through bilateral guide cannulae directed at the mPFC immediately after training on the IA task. Infusions of ODNs were given immediately after training to target the consolidation phase of memory processing and to avoid the potential for misleading non-memory-related performance effects of the drug. The infusion needles were 30-gauge microinfusion needles that were attached to 10-μL Hamilton microsyringes by polyethylene tubing (PE-20). The ODNs were backfilled into the needle and the infusion was driven by a minipump (Harvard Instruments). The injection needle protruded 1.5 mm beyond the cannula tip and a 0.5-μL injection volume was infused. Both scrambled and antisense ODNs (2.0 mM in 0.5 μL PBS) were infused at a rate of 0.2 μL/min and allowed an additional 2 min for diffusion.

2.9. Verification of ODN diffusion and knockdown

In order to determine the spread of the ODN infusion, a biotinylated Arc ODN was infused into the mPFC with the same dose used in behavioral experiments (2.0 mMin 0.5 μL PBS), at the same infusion rate and diffusion time. Rats were sacrificed 1, 3, and 6 h after the infusion for biotinylation analysis. Frozen brains were sectioned with a cryostat at 20-μm as described previously. The sections were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde and a standard nickel ABC-DAB reaction (Vector Laboratories) and thionin stain were used to visualize the spread of the infusion. To quantify the knockdown of Arc protein expression in the mPFC, Arc antisense ODNs were infused into the mPFC in one hemisphere and scrambled ODNs were infused into the mPFC of the other hemisphere with the infusion location being counterbalanced. Rats were sacrificed 1, 3, and 6 h after infusion. Three 500-μm sections were taken from frozen tissue with a cryostat and tissue punches were taken from the prelimbic region of the mPFC as described above. The frozen tissue punches were sonicated in a buffer containing 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 [containing 10% glycerol, 20% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich), and 10% protease inhibitor cocktail II (Sigma–Aldrich)]. Arc protein expression was measured using immunoblotting. In order to determine the specificity of the Arc As ODN, c-fos (rabbit; 1:250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and neurogranin (rabbit; 1:2000; Millipore) were also analyzed.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Inhibitory avoidance latencies to enter were analyzed with two-sample t-tests to make pair-wise comparisons between the vehicle-injected and corticosterone-injected groups. For Western blot densitometry results, Arc was normalized to actin and this ratio was then normalized to that from a cage control sample run on the same gel to account for film variation. Finally, those ratios were expressed as a percentage of the corresponding vehicle control group. For rats receiving BLA infusions, the western blot densitometry results were expressed as a ratio of Arc to actin and were then expressed as a ratio of the drug-infused hemisphere to the vehicle-infused hemisphere (or a ratio of the left hemisphere to the right hemisphere, or vice versa with analysis counterbalanced, if the rat received a bilateral vehicle infusion). Finally, those ratios were expressed as a percentage of the bilateral vehicle control group. The percentages were then analyzed using a two-factor ANOVA. For the behavioral intra-BLA propranolol experiment, inhibitory avoidance latencies to enter were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with Fischer’s post hoc tests. A probability level of p < .05 was considered significant. Data are presented as means + SEM.

3. Results

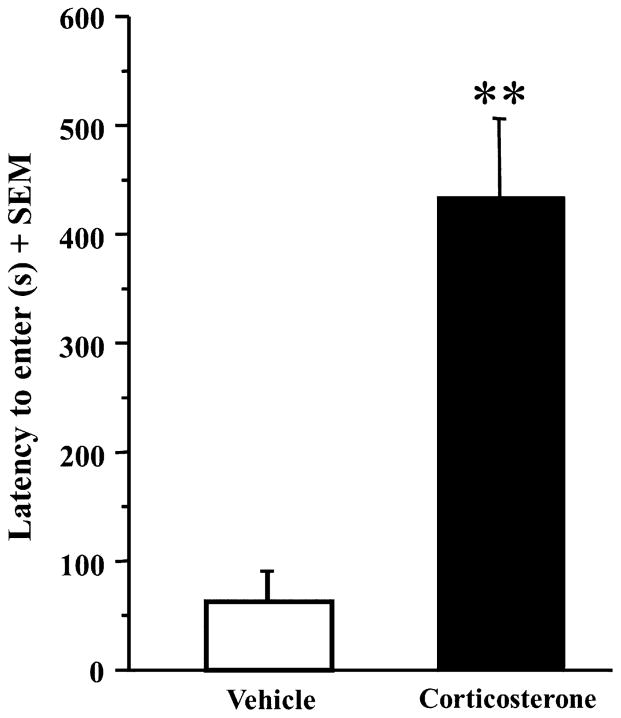

3.1. Immediate posttraining systemic injections of corticosterone enhance memory consolidation for the inhibitory avoidance task

Rats were trained on the inhibitory avoidance task and given immediate posttraining systemic injections of corticosterone (3 mg/kg) or vehicle. Training latencies did not significantly differ between corticosterone treated rats (mean training latency ± SEM: 23.71 s ± 7.04) and vehicle treated rats (mean training latency ± SEM: 17.13 s ± 3.49; t(13) = −.873; p = .40). However, a two-sample t-test revealed that the rats given posttraining corticosterone injections had a significantly higher latency to enter 48-h after training than vehicle-injected rats (Fig. 1; t(13) = −5.023; p < .001). Mean latencies for the corticosterone-injected rats (n = 7) were 435.14 s ± 30.90 and mean latencies for the vehicle-injected rats (n = 8) were 61.25 s ± 71.62.

Fig. 1.

Posttraining corticosterone enhances memory consolidation for the IA task. Rats that received immediate posttraining systemic injections of corticosterone (n = 7; 3 mg/kg) had significantly higher latency to enter than did vehicle-treated rats (n = 8; **p < .001). Data are presented as mean + SEM.

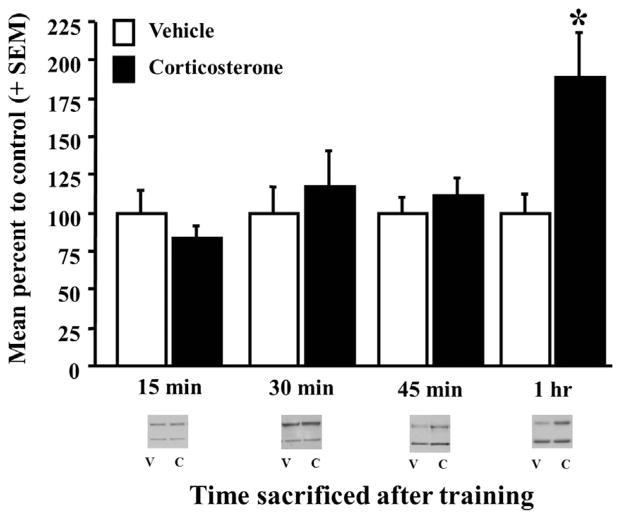

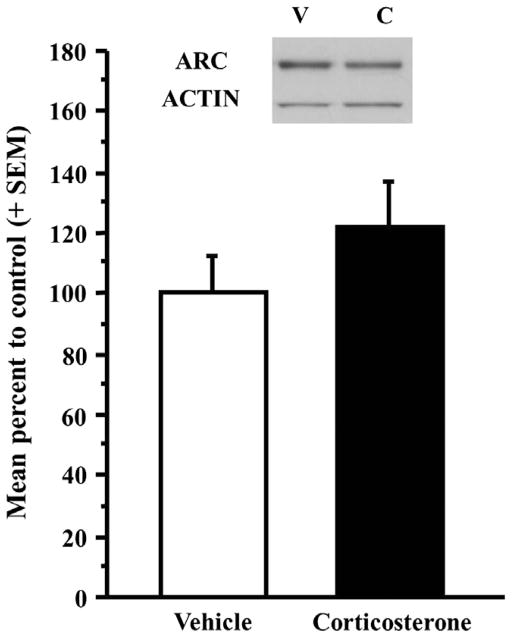

3.2. Immediate posttraining systemic injections of corticosterone increase Arc protein expression in medial prefrontal cortical synaptic tissue

In order to determine the effect of corticosterone on Arc protein expression in the medial prefrontal cortex, rats were trained on the inhibitory avoidance task, received immediate posttraining injections of either vehicle or corticosterone, and were sacrificed 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, or 1 h after training and drug treatment. To test the hypothesis that corticosterone influences synaptic expression of Arc in the mPFC, a synaptoneurosome preparation was used to assess Arc protein expression in synapses of the mPFC. A two-way ANOVA for percentage Arc protein expression showed a significant interaction effect between the two factors corticosterone and time (F(3,75) = 4.518, p < .01). Further analyses with Fisher’s post hoc tests did not reveal a significant difference in Arc protein expression in mPFC synaptic-enriched tissue between the vehicle- and corticosterone-injected rats at 15 min (Fig. 2: vehicle, n = 16, corticosterone, n = 21; p > .05), 30 min (Fig. 2: vehicle, n = 5, corticosterone, n = 6; p > .05), or 45 min (Fig. 2: vehicle, n = 6, corticosterone, n = 9; p > .05) after training and drug treatment but did reveal a significant difference at 1 h (Fig. 2: vehicle, n = 8, corticosterone, n = 12; p < .05). Because the significant increase was seen 1 h after training, all subsequent experiments examined Arc protein expression 1 h after training and drug treatment. In order to determine the effect of corticosterone on Arc expression in the mPFC in the absence of training, some rats were given systemic injections of either vehicle or corticosterone (3 mg/kg), sacrificed 1 h after the injection, and Arc protein expression was examined in mPFC synaptic enriched fractions. A two-sample t-test did not reveal a significant difference in Arc protein expression in mPFC synaptoneurosomes between vehicle-injected (n = 13) and corticosterone-injected rats (n = 13) when corticosterone was administered in the absence of training (Fig. 3; t(24) = −1.15, p = 0.26).

Fig. 2.

Posttraining corticosterone increases Arc protein expression in medial prefrontal cortical (mPFC) synaptoneurosome fractions. Western blot analysis of Arc protein expression at different time points following training and drug treatment. Memory-enhancing corticosterone (3 mg/kg) did not influence Arc protein expression in mPFC synaptoneurosome fractions at 15 min (vehicle: n = 16, corticosterone: n = 21), 30 min (vehicle: n = 5, corticosterone: n = 6), or 45 min (vehicle: n = 6, corticosterone: n = 9) after training. Posttraining systemic injections of corticosterone increased Arc protein expression 1 h after training (vehicle: n = 8, corticosterone: n = 12, p < .04). Representative western blot images are shown below each time point. Arc is the top band and actin is the bottom band. V = vehicle, C = corticosterone. Densitometry values for Arc bands were normalized to actin and to cage control and then presented as a percentage of the control vehicle group. Data are presented as mean + SEM.

Fig. 3.

Systemic injections of corticosterone do not increase Arc protein expression in the absence of training. Rats given systemic injections of corticosterone (3 mg/kg; n = 13) in the absence of training did not show a significant difference from vehicle-treated rats (n = 13). Densitometry values for Arc were normalized to actin and to cage control and then presented as a percentage of the control vehicle group. Representative western blot images are shown above the graph. V = vehicle, C = corticosterone. Data are presented as mean + SEM.

3.3. Post-training blockade of Arc protein expression in the mPFC using antisense oligodeoxynucleotides prevents long-term memory formation for the inhibitory avoidance task

To determine whether Arc protein expression is required in the mPFC for proper formation of long-term memories, as it is in the hippocampus, amygdala, and rostral anterior cingulate cortex, rats were trained on the inhibitory avoidance task and received immediate posttraining intra-mPFC infusions of Arc antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (As), or the control, scrambled (Scr), ODNs. A retention test was given 48 h after training. Only rats whose infusion needles terminated in the prelimbic region of the mPFC were used for analysis (Fig. 4). A two-sample t-test revealed that rats given intra-mPFC infusions of the Arc As ODNs showed significantly lower latencies to enter when compared to rats given intra-mPFC infusions of control Scr ODNs (Fig. 5; t(10) = 2.57, p < .05). Mean latency to enter for the Scr-infused group (n = 7) was 316.29 s ± 70.68 and the mean latency to enter for the As-infused group (n = 5) was 91.4 s ± 26.41, indicating that blockade of Arc protein expression in the mPFC significantly impaired long-term memory formation for the aversive inhibitory avoidance task.

Fig. 5.

Posttraining intra-mPFC infusions of Arc antisense oligodeoxynucleotides impairs memory consolidation of the inhibitory avoidance task. Rats that received immediate posttraining intra-mPFC infusions of the antisense ODN (n = 5; 2.0 mM in 0.5 μL PBS) had significantly lower latency to enter than did rats receiving intra-mPFC infusions of the scrambled ODN (n = 7; *p < .03). Data are presented as mean + SEM.

In order to assess the efficacy of the Arc As ODN infusions, some rats were given infusions of the As ODN into the mPFC of one hemisphere and the Scr ODN into the mPFC of the other hemisphere (Fig. 6E), and were sacrificed either 1 h, 3 h, or 6 h after training and drug treatment. These time points were selected because it has been demonstrated that 3 and 6 h after training are time points of maximal knockdown of Arc protein (Holloway & McIntyre, 2011; Ploski et al., 2008). When sacrificed 1 h after training and drug treatment, a 14% reduction of Arc protein was measured as a result of As ODN treatment (Fig. 6D). When sacrificed 3 h after training and drug treatment, a 44% reduction of Arc protein was measured as a result of As ODN treatment (Fig. 6D). When sacrificed 6 h after training and drug treatment, a 53% reduction in Arc protein was measured as a result of As ODN treatment (Fig. 6D). In order to assess the boundaries of the infusion, biotinylated As or Scr ODNs were infused into the mPFC after training on the IA task and rats were then sacrificed 1 h, 3 h, or 6 h after training and drug treatment. The area of diffusion was found to be limited to the prelimbic region of the mPFC and maximal diffusion was observed 1 h after training and drug treatment (Fig. 6A–C).

3.4. Posttraining blockade of basolateral amygdala norepinephrine blocks corticosterone-induced memory enhancement

Multiple studies indicate that glucocorticoid enhancement of memory is dependent upon noradrenergic activation in the BLA (Ferry, Roozendaal, & McGaugh, 1999; Quirarte, Roozendaal, & McGaugh, 1997; Roozendaal et al., 2006a; Roozendaal, Okuda, Van der Zee, & McGaugh, 2006b). In order to examine the influence of BLA noradrenergic activation on memory and Arc protein expression, rats were trained on the inhibitory avoidance task, received immediate posttraining systemic injections of corticosterone or vehicle and intra-BLA infusions of the β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol or vehicle. Rats (n = 17) were only used for analysis if the needle tips terminated in the BLA (Fig. 7). Fig. 8 shows the latency to enter in rats that received vehicle or corticosterone injections and intra-BLA infusions of either vehicle or propranolol. A two-way ANOVA for latency to enter showed a significant interaction effect between the two factors, injection (vehicle or corticosterone) and infusion (vehicle or propranolol; F(2,17) = 9.89, p < .01). Further analyses with Fisher’s post hoc tests showed that intra-BLA infusions of vehicle did not block the enhancing effect of corticosterone on latency to enter (p < .01, compared to vehicle-injected). Systemic vehicle injections together with intra-BLA propranolol administration had no significant effect on latency to enter (p = .45, compared to vehicle-infused). However, intra-BLA propranolol significantly attenuated the corticosterone-induced increase in latency to enter (p < .01, compared to vehicle-infused). Therefore, intra-BLA propranolol administration did not influence memory alone but did block corticosterone-induced enhancement of memory.

Fig. 8.

Posttraining blockade of BLA norepinephrine blocks corticosterone-induced memory enhancement. Rats given immediate posttraining intra-BLA infusions of vehicle and systemic injections of corticosterone (n = 3; 3 mg/kg) had significantly higher latency to enter than did vehicle-injected rats (n = 4; **p < .003). Rats from the vehicle-injected group given intra-BLA propranolol infusions (n = 6; 0.5 μg/0.2 μL) did not show any significant difference in latency to enter when compared to rats given intra-BLA infusions of vehicle (n = 4, p = .45). However, rats administered immediate posttraining corticosterone injections and intra-BLA infusions of propranolol (n = 4) showed significantly lower latency to enter than rats given corticosterone injections and intra-BLA infusions of vehicle (n = 3, p < .005). Data are presented as mean + SEM.

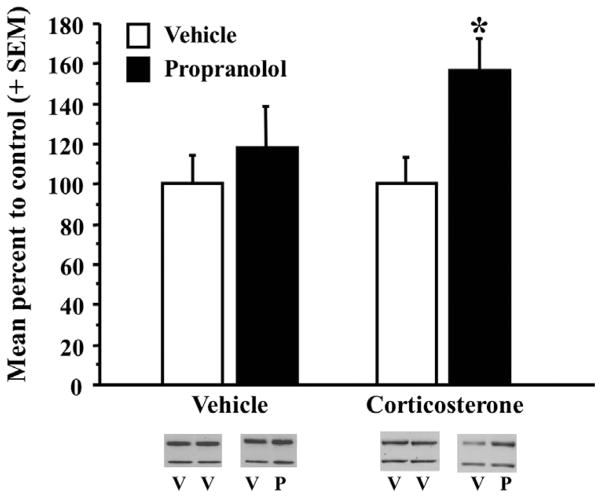

3.5. Posttraining blockade of basolateral amygdala norepinephrine increases corticosterone-induced Arc protein expression in mPFC synaptic enriched tissue

In order to determine whether blockade of BLA norepinephrine modulates Arc protein expression in the mPFC, rats were trained on the inhibitory avoidance task, given an immediate posttraining systemic injection of vehicle or corticosterone immediately followed by an infusion of propranolol into the BLA of one hemisphere and vehicle into the BLA of the opposite hemisphere or vehicle infused bilaterally into the BLA. Rats were sacrificed 1 h after training and drug treatment and Arc protein expression was examined in the mPFC ipsilateral to the hemisphere that received the propranolol infusion. Arc protein expression in the mPFC ipsilateral to the intra-BLA propranolol infusion was compared to expression in the mPFC ipsilateral to the intra-BLA vehicle infusion. Left vs. right hemispheres were also compared in rats given bilateral intra-BLA vehicle infusions. This design was used because it allows each animal to serve as its own control and limits the variability when comparing between animals (McIntyre et al., 2005). Arc was normalized to actin, then the drug-infused hemisphere was normalized to the vehicle-infused hemisphere (or randomly counterbalanced left-to-right or right-to-left for the bilateral vehicle-infused group), and was finally expressed as a percentage of the corresponding bilateral vehicle-infused group.

A two-way ANOVA for Arc expression showed a significant effect of the intra-BLA infusion (Fig. 9: vehicle/vehicle, n = 8, vehicle/propranolol, n = 8; corticosterone/vehicle, n = 6, corticosterone/propranolol, n = 9; F(1,27) = 4.971, p < .05) but no significant effect of injection (F(1,27) = 1.347, p = 0.25) or a significant interaction between the two (F1,27) = 1.347, p = 0.25). Further planned comparisons using a two-sample t-test did not reveal a significant difference in Arc protein expression in mPFC synaptic-enriched tissue between the propranolol-infused rats and the corresponding bilateral vehicle-infused rats from the systemic vehicle-injection group (Fig. 9: vehicle, n = 8, propranolol, n = 8; t(14) = −.72, p = .48). However, a two-sample t-test did reveal a significant increase in the percentage of Arc protein expression in mPFC synaptic-enriched tissue from the propranolol-infused rats as compared to the corresponding bilateral vehicle-infused rats when given posttraining systemic corticosterone (Fig. 9: vehicle, n = 6, propranolol, n = 9; t(13) = −2.58, p < .05). While blockade of BLA norepinephrine attenuated corticosterone-induced Arc protein upregulation in the dorsal hippocampus (McReynolds et al., 2010), the same treatment augmented the corticosterone-induced increase in Arc protein expression in the mPFC.

Fig. 9.

Posttraining blockade of BLA norepinephrine increases corticosterone-induced Arc protein expression in the mPFC. Western blot analysis of Arc protein expression from mPFC synaptic-enriched tissue 1 h after training and drug treatment. Rats administered immediate posttraining injections of corticosterone (3 mg/kg) and intra-BLA infusions of propranolol (n = 9; 0.5 μg/0.2 μL) had significantly greater Arc protein expression in mPFC synaptoneurosomes than did bilateral intra-BLA vehicle-infused rats (n = 6; *p < .05). Rats from the vehicle-injected group given intra-BLA propranolol (n = 8) did not show a significant difference in Arc protein expression when compared to rats administered bilateral intra-BLA infusions of vehicle (n = 8, p = .48). Representative western blot images are shown below each group. Arc is the top band and actin is the bottom band. V = vehicle, P = propranolol. Densitometry values for Arc were normalized to actin, then normalized to the vehicle infused hemisphere (or normalized to the opposite hemisphere in the case of bilateral vehicle infusions) and are presented as a percentage of the corresponding control vehicle group. Graph represents mean + SEM.

4. Discussion

The main finding of this study is that posttraining systemic administration of corticosterone increases Arc protein expression in synaptic-enriched fractions of the mPFC and Arc protein expression in the mPFC is necessary for consolidation of long-term memory for the aversive inhibitory avoidance task. Results are consistent with the previously observed effect in the hippocampus and support the hypothesis that corticosterone influences memory consolidation through an influence on expression of plasticity-related proteins in multiple memory-related brain regions. Interestingly, posttraining blockade of BLA norepinephrine prevented the corticosterone-induced enhancement of memory but increased Arc protein levels in the mPFC beyond those seen with posttraining corticosterone administration alone. In contrast, the same treatment resulted in attenuation of corticosterone-induced Arc protein expression in the hippocampus. The unexpected increase in mPFC Arc protein expression when memory enhancement and BLA β-adrenergic receptors were blocked suggests that the BLA is involved in the tight regulation of Arc protein to modulate plasticity and memory (McReynolds et al., 2010). These findings, taken together, support the conclusion that memory and Arc protein expression at the synapse is affected by stress and supports a role for the BLA in modulation of both memory and Arc protein expression in efferent brain regions.

Corticosterone is a memory-modulating stress hormone that crosses the blood–brain-barrier and binds to receptors in multiple brain regions, including the BLA, hippocampus, and mPFC (Meaney & Aitken, 1985; Rhees, Grosser, & Stevens, 1975; Roozendaal, 2002). In fact, acute stress increases corticosterone levels in the mPFC and dendritic remodeling occurs in the mPFC following exposure to mild stress (Brown, Henning, & Wellman, 2005; Garrido, De Blas, Gine, Santos, & Mora, 2012) suggesting that the mPFC plays a role in the stress response. Stress and corticosterone influence the consolidation of memory and the hippocampus and amygdala have been extensively studied for their role in this effect (Roozendaal et al., 2008). While there has long been an established role for the mPFC in the formation of working memory, which can be disrupted by stress, a proposed role has more recently emerged for the mPFC in stress effects on memory consolidation (Arnsten, 2009; Roozendaal, McReynolds, & McGaugh, 2004). The prelimbic region of the mPFC is critical for expression of conditioned fear and consolidation of inhibitory avoidance memory (Barsegyan et al., 2010; Corcoran & Quirk, 2007). In addition, exposure to a conditioned stimulus following an aversive conditioning task increases levels of the monoamines norepinephrine and dopamine in the mPFC and training on the aversive inhibitory avoidance task increases expression of the plasticity-related immediate-early gene Arc (Feenstra, Vogel, Botterblom, Joosten, & de Bruin, 2001; Zhang, Fukushima, & Kida, 2011). The present findings are consistent with evidence that the mPFC is involved in stress hormone enhancement of memory as we observed an increase in Arc protein expression in the prelimbic region of the mPFC when rats were trained on the inhibitory avoidance (IA) task and given posttraining injections of corticosterone. The increase in Arc protein was only seen when corticosterone was paired with training on the IA task. Consistent with previous findings, corticosterone administered alone did not result in an increase in Arc protein (McReynolds et al., 2010). Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that stress and stress hormones influence the brain on a systems level by influencing the mPFC, in addition to the BLA and hippocampus, to modulate the consolidation of aversive memories.

Arc protein expression is critical for some forms of long-term plasticity and memory. Arc protein expression in the hippocampus is necessary for the maintenance of LTP and consolidation of spatial memories (Guzowski et al., 2000). Furthermore a role for Arc has been established in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex, lateral amygdala, and hippocampus in the consolidation of aversive memories while having no effect on acquisition or retrieval (Holloway & McIntyre, 2011; McIntyre et al., 2005; Ploski et al., 2008). Arc mRNA is trafficked out to the dendrites where it may undergo local translation at the synapse (Steward et al., 1998; Yin et al., 2002). Previous findings indicate that adrenal hormones influence expression of Arc mRNA in the mPFC (Mikkelsen & Larsen, 2006). The increase in Arc protein expression seen here in synaptic-enriched mPFC fractions, suggests that stress may also affect local translation of Arc, and thereby modulate synaptic plasticity in the mPFC, to influence memory consolidation. Though the mPFC is involved in the consolidation of memory for the IA task it was unknown whether Arc protein expression in the mPFC was necessary for memory. Here we showed that blockade of Arc protein in the mPFC impairs long-term formation of memory for the IA task. We did not directly test the role of corticosterone-induced elevation of Arc on memory consolidation because intra-mPFC administration of antisense ODNs impaired memory consolidation on its own, making a potential blockade of corticosterone enhancement of memory, by a memory impairing treatment, difficult to interpret. However, the present findings support the hypothesis that Arc protein expression is not merely an activity marker, but serves a functional role in long-term formation of memory in multiple memory-related brain regions.

Glucocorticoid effects on memory require noradrenergic activation in the BLA for a multitude of learning and memory tasks (Quirarte et al., 1997; Roozendaal et al., 2004; Roozendaal et al., 2006a; Roozendaal et al., 2006b) and these findings are corroborated by human studies (de Quervain et al., 2009; van Stegeren et al., 2007). Moreover, memory-enhancing posttraining systemic injections of corticosterone increase norepinephrine levels in the BLA, further demonstrating an interaction between the two systems (McReynolds et al., 2010). The present findings reaffirm the critical role of BLA norepinephrine in the glucocorticoid influence on memory. Here we show that posttraining intra-BLA administration of the β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol blocks corticosterone-induced enhancement of memory consolidation without influencing memory when administered alone. This BLA treatment attenuated corticosterone-induced Arc protein expression in enriched synaptic tissue in the hippocampus, indicating a role for BLA norepinephrine in stress-induced neuroplasticity (McReynolds et al., 2010). However, posttraining intra-BLA infusions of propranolol augment the corticosterone-induced increase in Arc protein expression in mPFC synaptic-enriched tissue. These divergent findings may reflect differential roles of the mPFC and the hippocampus in memory and/or a difference in connectivity with the BLA. One influence the BLA exerts on the mPFC is inhibitory, either directly through glutamatergic projection neurons terminating on mPFC interneurons, or indirectly through the mediodorsal thalamus (Bacon, Headlam, Gabbott, & Smith, 1996; Rotaru, Barrionuevo, & Sesack, 2005). Stimulation of the BLA reduces spontaneous firing in the mPFC (Floresco & Tse, 2007; Perez-Jaranay & Vives, 1991). Because systemic administration of the β-adrenoceptor antagonist, propranolol, decreases spontaneous firing within the BLA (Buffalari & Grace, 2007), it is possible that the increase observed in mPFC Arc protein expression following intra-BLA propranolol administration is a result of decreased BLA activity and subsequent disinhibition of the mPFC. In a highly relevant previous study, van Stegeren and colleagues found that, although successful encoding of emotional material was related to increased activity in the mPFC, combined administration of the noradrenergic stimulant yohimbine and the corticosteroid hydrocortisone enhanced memory and, when combined, produced a different pattern of activity. Notably, drug-induced elevations of noradrenaline and cortisol decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex (van Stegeren, Roozendaal, Kindt, Wolf, & Joëls, 2010). This result is consistent with the present finding that the combination of corticosterone with blockade of noradrenaline receptors in the BLA increased expression of a marker of synaptic activity and plasticity in the mPFC when compared with administration of corticosterone alone. The present findings suggest that BLA norepinephrine plays a role in stress-induced neuroplasticity in the mPFC, though the direction of the modulation appears to differ between the hippocampus and mPFC.

Arc expression requires tight regulation and disruption in this regulation results in aberrant plasticity (Shepherd & Bear, 2011). For example, in mice lacking the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), a negative regulator of Arc, Arc protein expression is upregulated and animals exhibit cognitive dysfunction (Brennan, Albeck, & Paylor, 2006; McNaughton et al., 2008; Ventura, Pascucci, Catania, Musumeci, & Puglisi-Allegra, 2004; Zalfa et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2005). Disruption of regulation of Arc also occurs in mice lacking the Ube3A protein, an ubiquination ligase enzyme that targets Arc protein for degradation. In these mice, Arc protein remains upregulated and animals show abnormal synaptic plasticity (Dindot, Antalffy, Bhattacharjee, & Beaudet, 2008; Greer et al., 2010; Mardirossian, Rampon, Salvert, Fort, & Sarda, 2009). These studies support the emerging hypothesis that tight regulation of Arc expression is necessary for normal plasticity and memory. This may explain why, under conditions where memory enhancement is blocked, we observed an increase in Arc protein expression in the mPFC. Though parallel effects on memory and Arc expression have been observed, the relationship between the two is not necessarily linear. These data support the hypothesis that the BLA participates in the negative or positive regulation of Arc protein expression in efferent brain regions.

5. Conclusion

Results support a role for stress and stress hormone effects on neuroplasticity, particularly synaptic expression of the plasticity-associated protein Arc, in the consolidation of emotionally arousing memories. Arc protein expression plays a critical role in the consolidation of long-term memories. Here, it is evident that stress-induced modulation of Arc expression occurs in the mPFC as well as in the hippocampus. A negative relationship between Arc expression in the mPFC and memory performance, following intra-BLA infusions of propranolol, suggests that amygdala modulation of Arc is not necessarily unidirectional. The BLA may act to optimize memory consolidation processes by increasing or decreasing Arc protein expression in synapses in efferent regions of the brain.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jon Ploski for helpful feedback on a draft of this manuscript. This research was funded by the Department of Behavioral and Brain Sciences at The University of Texas at Dallas.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(6):410–422. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648. nrn2648 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon SJ, Headlam AJ, Gabbott PL, Smith AD. Amygdala input to medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) in the rat: A light and electron microscope study. Brain Research. 1996;720(1–2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00155-2. 0006-8993(96)00155-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsegyan A, Mackenzie SM, Kurose BD, McGaugh JL, Roozendaal B. Glucocorticoids in the prefrontal cortex enhance memory consolidation and impair working memory by a common neural mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academic Science United States of America. 2010;107(38):16655–16660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011975107. 1011975107 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan FX, Albeck DS, Paylor R. Fmr1 knockout mice are impaired in a leverpress escape/avoidance task. Genes Brain Behavior. 2006;5(6):467–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00183.x. GBB183 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Henning S, Wellman CL. Mild, short-term stress alters dendritic morphology in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15(11):1714–1722. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi048. bhi048 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, Grace AA. Noradrenergic modulation of basolateral amygdala neuronal activity: Opposing influences of alpha-2 and beta receptor activation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(45):12358–12366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2007-07.2007. 27/45/12358 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Prins B, Weber M, McGaugh JL. Beta-adrenergic activation and memory for emotional events. Nature. 1994;371(6499):702–704. doi: 10.1038/371702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Quirk GJ. Activity in prelimbic cortex is necessary for the expression of learned, but not innate, fears. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(4):840–844. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5327-06.2007. 27/4/840 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ, Aerni A, Schelling G, Roozendaal B. Glucocorticoids and the regulation of memory in health and disease. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2009;30(3):358–370. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.03.002. S0091-3022(09)00003-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Stress and glucocorticoids impair retrieval of long-term spatial memory. Nature. 1998;394(6695):787–790. doi: 10.1038/29542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dindot SV, Antalffy BA, Bhattacharjee MB, Beaudet AL. The Angelman syndrome ubiquitin ligase localizes to the synapse and nucleus, and maternal deficiency results in abnormal dendritic spine morphology. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008;17(1):111–118. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm288. ddm288 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcos F, LaBar KS, Cabeza R. Interaction between the amygdala and the medial temporal lobe memory system predicts better memory for emotional events. Neuron. 2004;42(5):855–863. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00289-2. S0896627304002892 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra MG, Vogel M, Botterblom MH, Joosten RN, de Bruin JP. Dopamine and noradrenaline efflux in the rat prefrontal cortex after classical aversive conditioning to an auditory cue. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;13(5):1051–1054. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01471.x. ejn1471 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry B, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Basolateral amygdala noradrenergic influences on memory storage are mediated by an interaction between beta- and alpha1-adrenoceptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19(12):5119–5123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-05119.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Tse MT. Dopaminergic regulation of inhibitory and excitatory transmission in the basolateral amygdala-prefrontal cortical pathway. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(8):2045–2057. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5474-06.2007. 27/8/2045 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido P, De Blas M, Gine E, Santos A, Mora F. Aging impairs the control of prefrontal cortex on the release of corticosterone in response to stress and on memory consolidation. Neurobiology Aging. 2012;33(4):827 e821–829. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.011. S0197-4580(11)00228-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold PE, van Buskirk RB, McGaugh JL. Effects of hormones on time-dependent memory storage processes. Progress in Brain Research. 1975;42:210–211. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63665-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer PL, Hanayama R, Bloodgood BL, Mardinly AR, Lipton DM, Flavell SW, et al. The Angelman Syndrome protein Ube3A regulates synapse development by ubiquitinating arc. Cell. 2010;140(5):704–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.026. S0092-8674(10)00061-9 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Lyford GL, Stevenson GD, Houston FP, McGaugh JL, Worley PF, et al. Inhibition of activity-dependent arc protein expression in the rat hippocampus impairs the maintenance of long-term potentiation and the consolidation of long-term memory. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(11):3993–4001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-03993.2000. 20/11/3993 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JP, Morey RA, Petty CM, Seth S, Smoski MJ, McCarthy G, et al. Staying cool when things get hot: Emotion regulation modulates neural mechanisms of memory encoding. Front Human Neuroscience. 2010;4:230. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway CM, McIntyre CK. Post-training disruption of Arc protein expression in the anterior cingulate cortex impairs long-term memory for inhibitory avoidance training. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2011;95(4):425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.02.002. S1074-7427(11)00028-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway-Erickson CM, McReynolds JR, McIntyre CK. Memory-enhancing intra-basolateral amygdala infusions of clenbuterol increase Arc and CaMKIIalpha protein expression in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex. Front Behavior Neuroscience. 2012;6:17. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper ML, Chiasson BJ, Robertson HA. Infusion into the brain of an antisense oligonucleotide to the immediate-early gene c-fos suppresses production of fos and produces a behavioral effect. Neuroscience. 1994;63(4):917–924. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90559-2. 0306-4522(94)90559-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui GK, Figueroa IR, Poytress BS, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL, Weinberger NM. Memory enhancement of classical fear conditioning by post-training injections of corticosterone in rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2004;81(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2003.09.002. S1074742703001126 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegaya Y, Saito H, Abe K. Attenuated hippocampal long-term potentiation in basolateral amygdala-lesioned rats. Brain Research. 1994;656(1):157–164. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91377-3. 0006-8993(94)91377-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardirossian S, Rampon C, Salvert D, Fort P, Sarda N. Impaired hippocampal plasticity and altered neurogenesis in adult Ube3a maternal deficient mouse model for Angelman syndrome. Experimental Neurology. 2009;220(2):341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.08.035. S0014-4886(09)00384-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Organization of amygdaloid projections to the prefrontal cortex and associated striatum in the rat. Neuroscience. 1991;44(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90247-l. 0306-4522(91)90247-L [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. The Amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CK, Miyashita T, Setlow B, Marjon KD, Steward O, Guzowski JF, et al. Memory-influencing intra-basolateral amygdala drug infusions modulate expression of Arc protein in the hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academic Science United States of America. 2005;102(30):10718–10723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504436102. 0504436102 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton CH, Moon J, Strawderman MS, Maclean KN, Evans J, Strupp BJ. Evidence for social anxiety and impaired social cognition in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008;122(2):293–300. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.2.293. 2008-03769-005 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McReynolds JR, Donowho K, Abdi A, McGaugh JL, Roozendaal B, McIntyre CK. Memory-enhancing corticosterone treatment increases amygdala norepinephrine and Arc protein expression in hippocampal synaptic fractions. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2010;93(3):312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.11.005. S1074-7427(09)00215-9 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Aitken DH. [3H]Dexamethasone binding in rat frontal cortex. Brain Research. 1985;328(1):176–180. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91340-x. 0006-8993(85)91340-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen JD, Larsen MH. Effects of stress and adrenalectomy on activity-regulated cytoskeleton protein (Arc) gene expression. Neuroscience Letters. 2006;403(3):239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.04.040. S0304-3940(06)00427-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murty VP, Ritchey M, Adcock RA, LaBar KS. FMRI studies of successful emotional memory encoding: A quantitative meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(12):3459–3469. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.07.030. S0028-3932(10)00335-0 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 5. San Diego: Academic Press; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Jaranay JM, Vives F. Electrophysiological study of the response of medial prefrontal cortex neurons to stimulation of the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala in the rat. Brain Research. 1991;564(1):97–101. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91357-7. 0006-8993(91)91357-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploski JE, Pierre VJ, Smucny J, Park K, Monsey MS, Overeem KA, et al. The activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein (Arc/Arg3.1) is required for memory consolidation of pavlovian fear conditioning in the lateral amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(47):12383–12395. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1662-08.2008. 28/47/12383 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirarte GL, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoid enhancement of memory storage involves noradrenergic activation in the basolateral amygdala. Proceedings of the National Academic Science United States of America. 1997;94(25):14048–14053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JM, de Kloet ER. Two receptor systems for corticosterone in rat brain: Microdistribution and differential occupation. Endocrinology. 1985;117(6):2505–2511. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-6-2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhees RW, Grosser BI, Stevens W. The autoradiographic localization of (3H)dexamethasone in the brain and pituitary of the rat. Brain Research. 1975;100(1):151–156. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90251-6. 0006-8993(75)90251-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B. Stress and memory: Opposing effects of glucocorticoids on memory consolidation and memory retrieval. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2002;78(3):578–595. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4080. S1074742702940803 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Barsegyan A, Lee S. Adrenal stress hormones, amygdala activation, and memory for emotionally arousing experiences. Progress in Brain Research. 2008;167:79–97. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67006-X. S0079-6123(07)67006-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Hui GK, Hui IR, Berlau DJ, McGaugh JL, Weinberger NM. Basolateral amygdala noradrenergic activity mediates corticosterone-induced enhancement of auditory fear conditioning. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2006a;86(3):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.03.003. S1074-7427(06)00032-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, McReynolds JR, McGaugh JL. The basolateral amygdala interacts with the medial prefrontal cortex in regulating glucocorticoid effects on working memory impairment. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(6):1385–1392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4664-03.2004. 24/6/1385 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, McReynolds JR, Van der Zee EA, Lee S, McGaugh JL, McIntyre CK. Glucocorticoid effects on memory consolidation depend on functional interactions between the medial prefrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(45):14299–14308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3626-09.2009. 29/45/14299 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Okuda S, Van der Zee EA, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoid enhancement of memory requires arousal-induced noradrenergic activation in the basolateral amygdala. Proceedings of the National Academic Science United States of America. 2006b;103(17):6741–6746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601874103. 0601874103 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotaru DC, Barrionuevo G, Sesack SR. Mediodorsal thalamic afferents to layer III of the rat prefrontal cortex: Synaptic relationships to subclasses of interneurons. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;490(3):220–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.20661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JD, Bear MF. New views of Arc, a master regulator of synaptic plasticity. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14(3):279–284. doi: 10.1038/nn.2708. nn.2708 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Wallace CS, Lyford GL, Worley PF. Synaptic activation causes the mRNA for the IEG Arc to localize selectively near activated postsynaptic sites on dendrites. Neuron. 1998;21(4):741–751. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80591-7. S0896-6273(00)80591-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stegeren AH, Roozendaal B, Kindt M, Wolf OT, Joëls M. Interacting noradrenergic and corticosteroid systems shift human brain activation patterns during encoding. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2010;93(1):56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stegeren AH, Wolf OT, Everaerd W, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, Rombouts SA. Endogenous cortisol level interacts with noradrenergic activation in the human amygdala. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2007;87(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura R, Pascucci T, Catania MV, Musumeci SA, Puglisi-Allegra S. Object recognition impairment in Fmr1 knockout mice is reversed by amphetamine: Involvement of dopamine in the medial prefrontal cortex. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2004;15(5–6):433–442. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200409000-00018. 00008877-200409000-00018 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widnell KL, Self DW, Lane SB, Russell DS, Vaidya VA, Miserendino MJ, et al. Regulation of CREB expression: In vivo evidence for a functional role in morphine action in the nucleus accumbens. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1996;276(1):306–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Edelman GM, Vanderklish PW. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances synthesis of Arc in synaptoneurosomes. Proceedings of the National Academic Science United States of America. 2002;99(4):2368–2373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042693699. 042693699 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalfa F, Giorgi M, Primerano B, Moro A, Di Penta A, Reis S, et al. The fragile X syndrome protein FMRP associates with BC1 RNA and regulates the translation of specific mRNAs at synapses. Cell. 2003;112(3):317–327. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00079-5. S0092867403000795 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Fukushima H, Kida S. Induction and requirement of gene expression in the anterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex for the consolidation of inhibitory avoidance memory. Molecular Brain. 2011;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-4. 1756-6606-4-4 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao MG, Toyoda H, Ko SW, Ding HK, Wu LJ, Zhuo M. Deficits in trace fear memory and long-term potentiation in a mouse model for fragile X syndrome. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(32):7385–7392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1520-05.2005. 25/32/7385 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]