Abstract

We consider estimation of and inference for the mean outcome under the optimal dynamic two time-point treatment rule defined as the rule that maximizes the mean outcome under the dynamic treatment, where the candidate rules are restricted to depend only on a user-supplied subset of the baseline and intermediate covariates. This estimation problem is addressed in a statistical model for the data distribution that is nonparametric beyond possible knowledge about the treatment and censoring mechanism. This contrasts from the current literature that relies on parametric assumptions. We establish that the mean of the counterfactual outcome under the optimal dynamic treatment is a pathwise differentiable parameter under conditions, and develop a targeted minimum loss-based estimator (TMLE) of this target parameter. We establish asymptotic linearity and statistical inference for this estimator under specified conditions. In a sequentially randomized trial the statistical inference relies upon a second-order difference between the estimator of the optimal dynamic treatment and the optimal dynamic treatment to be asymptotically negligible, which may be a problematic condition when the rule is based on multivariate time-dependent covariates. To avoid this condition, we also develop TMLEs and statistical inference for data adaptive target parameters that are defined in terms of the mean outcome under the estimate of the optimal dynamic treatment. In particular, we develop a novel cross-validated TMLE approach that provides asymptotic inference under minimal conditions, avoiding the need for any empirical process conditions. We offer simulation results to support our theoretical findings.

Keywords: sequentially randomized controlled trial, cross-validation, dynamic treatment, optimal dynamic treatment, targeted minimum loss-based estimation

1 Introduction

Suppose we observe n in4dependent and identically distributed observations of a time-dependent random variable consisting of baseline covariates, initial treatment and censoring indicator, intermediate covariates, subsequent treatment and censoring indicator, and a final outcome. For example, this could be data generated by a sequentially randomized controlled trial (RCT) in which one follows up a group of subjects, and treatment assignment at two time points is sequentially randomized, where the probability of receiving treatment might be determined by a baseline covariate for the first-line treatment, and time-dependent intermediate covariate (such as a biomarker of interest) for the second-line treatment [1]. Such trials are often called sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (SMART). A dynamic treatment rule deterministically assigns treatment as a function of the available history. If treatment is assigned at two time points, then this dynamic treatment rule consists of two rules, one for each time point [1–4]. The mean outcome under a dynamic treatment is a counterfactual quantity of interest representing what the mean outcome would have been if everybody would have received treatment according to the dynamic treatment rule [5–11]. Dynamic treatments represent prespecified multiple time-point interventions that at each treatment-decision stage are allowed to respond to the currently available treatment and covariate history. Examples of multiple time-point dynamic treatment regimes are given in Lavori and Dawson [12, 13]; Murphy [14]; Rosthøj et al. [15]; Thall et al. [16, 17]; Wagner et al. [18]; Petersen et al. [19]; van der Laan and Petersen [20]; and Robins et al. [21], ranging from rules that change the dose of a drug, change or augment the treatment, to making a decision on when to start a new treatment, in response to the history of the subject.

More recently, SMART designs have been implemented in practice: Lavori and Dawson [12, 22]; Murphy [14]; Thall et al. [16]; Chakraborty et al. [23]; Kasari [24]; Lei et al. [25]; Nahum-Shani et al. [26, 27]; Jones [28]; Lei et al. [25]. For an extensive list of SMARTs, we refer the reader to the website http://methodology.psu.edu/ra/adap-inter/projects. For an excellent and recent overview of the literature on dynamic treatments we refer to Chakraborty and Murphy [29].

We define the optimal dynamic multiple time-point treatment regime as the rule that maximizes the mean outcome under the dynamic treatment, where the candidate rules are restricted to only respond to a user-supplied subset of the baseline and intermediate covariates. The literature on Q-learning shows that we can describe the optimal dynamic treatment among all dynamic treatments in a sequential manner [14, 30–33]. The optimal rule can be learned through fitting the likelihood and then calculating the optimal rule under this fit of the likelihood. This approach can be implemented with maximum likelihood estimation based on parametric models. It has been noted (e.g., Robins [32], Chakraborty and Murphy [29]) that the estimator of the parameters of one of the regressions (except the first one) when using parametric regression models is a non-smooth function of the estimator of the parameters of the previous regression, and that this results in non-regularity of the estimators of the parameter vector. This raises challenges for obtaining statistical inference, even when assuming that these parametric regression models are correctly specified. Chakraborty and Murphy [29] discuss various approaches and advances that aim to resolve this delicate issue such as inverting hypothesis testing [32], establishing non-normal limit distributions of the estimators (E. Laber, D. Lizotte, M. Qian, S. Murphy, submitted), or using the m out of n bootstrap.

Murphy [30] and Robins [31, 32] developed structural nested mean models tailored to optimal dynamic treatments. These models assume a parametric model for the “blip function” defined as the additive effect of a blip in current treatment on a counterfactual outcome, conditional on the observed past, in the counterfactual world in which future treatment is assigned optimally. Statistical inference for the parameters of the blip function proceeds accordingly, but Robins [32] points out the irregularity of the estimator, resulting in some serious challenges for statistical inference as referenced above. Structural nested mean models have also been generalized to blip functions that condition on a (counterfactual) subset of the past, thereby allowing the learning of optimal rules that are restricted to only using this subset of the past [32] and Section 6.5 in van der Laan and Robins [34].

An alternative approach, referenced as the direct approach in Chakraborty and Murphy [29], uses marginal structural models (MSMs) for the dynamic regime-specific mean outcome for a user-supplied class of dynamic treatments. If one assumes the marginal structural models are correctly specified, then the parameters of the marginal structural model map into a dynamic treatment that is optimal among the user-supplied class of dynamic regimes. In addition, the MSM also provides the complete dose–response curve, that is, the mean counterfactual outcome for each dynamic treatment in the user-supplied class. This generalization of the original marginal structural models for static interventions to MSMs for dynamic treatments was developed independently by Orellana et al. [35]; van der Laan and Petersen [20]. These articles present inverse probability of treatment and censoring weighted (IPCW) estimators and double robust augmented IPCW estimators based on general longitudinal data structures, allowing for right censoring, time-dependent covariates, and survival outcomes. Double robust estimating equation-based methods that estimate the nuisance parameters with sequential parametric regression models using clever covariates were developed for static intervention MSMs by Bang and Robins [36]. An analogous targeted minimum loss-based estimator (TMLE) [37–39] was developed for marginal structural models for a user-supplied class of dynamic treatments by Petersen et al. [40]. This estimator builds on the TMLE for the mean outcome for a single dynamic treatment developed by van der Laan and Gruber [41]. Additional application papers of interest are [42–44] which involve fitting MSMs for dynamic treatments defined by treatment-tailoring threshold using IPCW methods.

Each of the above referenced approaches for learning an optimal dynamic treatment that also aims to provide statistical inference relies on parametric assumptions: obviously, Q-learning based on parametric models, but also the structural nested mean models and the marginal structural models both rely on parametric models for the blip function and dose–response curve, respectively. As a consequence, even in a SMART, the statistical inference for the optimal dynamic treatment heavily relies on assumptions that are generally believed to be false, and will thus be expected to be biased.

To avoid such biases, we define the statistical model for the data distribution as nonparametric, beyond possible knowledge about the treatment mechanism (e.g., known in an RCT) and censoring mechanism. This forces us to define the optimal dynamic treatment and the corresponding mean outcome as parameters defined on this nonparametric model, and to develop data adaptive estimators of the optimal dynamic treatment. In order to not only consider the most ambitious fully optimal rule, we define the V-optimal rules as the optimal rule that only uses a user-supplied subset V of the available covariates. This allows us to consider suboptimal rules that are easier to estimate and thereby allow for statistical inference for the counterfactual mean outcome under the suboptimal rule. This is analogous to the generalized structural nested mean models whose blip functions only condition on a counterfactual subset of the past. In a companion article we describe how to estimate the V-optimal rule.

In Example 4 of Robins et al. [45], the authors develop an asymptotic confidence set for the optimal treatment regime in an RCT under a large semiparametric model that only assumes that the treatment mechanism is known. This confidence set is certainly of interest and warrants further consideration in the optimal treatment literature. They get this confidence set by deriving the efficient influence curve for the mean squared blip function. They propose selecting a data adaptive estimate of the optimal treatment rule by a particular cross-validation scheme over a set of basis functions, and show that this estimator achieves a data adaptive rate of convergence under smoothness assumptions on the blip function. Our work is distinct from this earlier work in that the earlier work does not directly consider the mean outcome under the optimal rule and only considers data generated by a point treatment RCT.

In this article we describe how to obtain semiparametric inference about the mean outcome under the two time point V-optimal rule. We will show that the mean outcome under the optimal rule is a pathwise differentiable parameter of the data distribution, indicating that it is possible to develop asymptotically linear estimators of this target parameter under conditions. In fact, we obtain the surprising result that the pathwise derivative of this target parameter equals the pathwise derivative of the mean counterfactual outcome under a given dynamic treatment rule set at the optimal rule, treating the latter as known. By a reference to the current literature for double robust and efficient estimation of the mean outcome under a given rule, we then obtain a TMLE for the mean outcome under the optimal rule. Subsequently, we prove asymptotic linearity and efficiency of this TMLE, allowing us to construct confidence intervals for the mean outcome under the optimal dynamic treatment or its contrast with respect to a standard treatment. Thus, contrary to the irregularity of the estimators of the unknown parameters in the semiparametric structural nested mean model, we can construct regular estimators of the mean outcome under the optimal rule in the nonparametric model.

In a SMART the statistical inference would only rely upon a second-order difference between the estimator of the optimal dynamic treatment and the optimal dynamic treatment itself to be asymptotically negligible. This is a reasonable condition if we restrict ourselves to rules only responding to a one-dimensional time-dependent covariate, or if we are willing to make smoothness assumptions. To avoid this condition, we also develop TMLEs and statistical inference for data adaptive target parameters that are defined in terms of the mean outcome under the estimate of the optimal dynamic treatment (see van der Laan et al. [46] for a general approach for statistical inference for data adaptive target parameters). In particular, we develop a novel cross-validated TMLE (CV-TMLE) approach that provides asymptotic inference under minimal conditions.

For the sake of presentation, we focus on two time point treatments in this article. In the appendices of our earlier technical reports [47, 48] we generalize these results to general multiple time point treatments, and develop general (sequential) super-learning based on the efficient CV-TMLE of the risk of a candidate estimator. In this appendix we also develop a TMLE of a projection of the blip functions on a parametric working model (with corresponding statistical inference, which presents a result of interest in its own right). We emphasize that this technical report is distinct from our companion paper in this issue, which focuses on the data adaptive estimation of optimal treatment strategies.

1.1 Organization of article

Section 2 defines the mean outcome under the optimal rule as a causal parameter and gives identifiability assumptions under which the causal parameter is identified with a statistical parameter of the observed data distribution.

The remainder of the paper describes strategies to estimate the counterfactual mean outcome under the optimal rule and related quantities. This paper assumes that we have an estimate of the optimal rule in our semiparametric model. In our companion paper we describe how to obtain estimates of the V-optimal rule.

The first part of this article concerns estimation of the mean outcome under the optimal rule. Section 3 establishes the pathwise differentiability of the mean outcome under the V-optimal rule conditions. A closed form expression for the efficient influence curve for this statistical parameter is given, which represents a key ingredient in semiparametric inference for the statistical target parameter. We obtain the surprising result that, under straightforward conditions, estimating the mean outcome under the unknown optimal treatment rule is the same in first order as estimating the mean outcome under the optimal rule when the rule is known from the outset. Section 4 presents the key properties of a TMLE for the mean outcome under the optimal rule, which is presented in detail in “TMLE of the mean outcome under a given rule” in Appendix B due to its similarity to TMLEs presented previously in the literature. Section 5 presents an asymptotic linearity theorem for this TMLE and corresponding statistical inference.

The second part of this article concerns statistical inference for data adaptive target parameters that are defined in terms of the mean outcome under the estimate of the optimal dynamic treatment, thereby avoiding the consistency and rate condition for the fitted V-optimal rule as required for asymptotic linearity of the TMLE of the mean outcome under the actual V-optimal rule. These results are of interest in practice because an estimated, possibly suboptimal, rule will be implemented in the population, not some unknown optimal rule. Section 6 presents an asymptotic linearity theorem for the TMLE presented in Section 4, but now with the target parameter defined as the mean outcome under the estimated rule. In Section 7 we present the CV-TMLE framework. A specific CV-TMLE algorithm is described in “CV-TMLE of the mean outcome under data adaptive V-optimal rule” in Appendix B due to its similarity to CV-TMLEs presented previously in the literature. The CV-TMLE provides asymptotic inference under minimal conditions for the mean outcome under a dynamic treatment fitted on a training sample, averaged across the different splits in training sample and validation sample. Both results allow us to construct confidence intervals that have the correct asymptotic coverage of the random true target parameter, and the fixed mean outcome under the optimal rule under conditions, but statistical inference based on the CV-TMLE does not require an empirical process condition that would put a brake on the allowed data adaptivity of the estimator.

Section 8 presents the simulation methods. The simulations estimate the optimal rule using an ensemble algorithm presented in our companion paper, and then given this estimate apply the estimators of the optimal rule presented in this paper. Section 9 presents the coverage and efficiency of the various estimators in our simulation. Appendix C gives analytic intuition as to why some of the simulation results may have occurred. Section 10 closes with a discussion and directions for future work.

All proofs can be found in Appendix A.

2 Formulation of optimal dynamic treatment estimation problem

Suppose we observe n i.i.d. copies of

where A(j) = (A1(j), A2(j)), A1(j) is a binary treatment, and A2(j) is an indicator of not being right censored at “time” j, j = 0, 1. That is, A2(0) = 0 implies that (L(1), A1(1), Y) is n ot observed, and A2(1) = 0 implies that Y is not observed. Each time point j has covariates L(j) that precede treatment, j = 0, 1, and the outcome of interest is given by Y and occurs after time point 1. For a time-dependent process X(·), we use the notation , where . Let be a statistical model that makes no assumptions on the marginal distribution Q0,L(0) of L(0) and the conditional distribution Q0,L(1) of L(1), given A(0), L(0), but might make assumptions on the conditional distributions g0A(j) of A(j), given , , j = 0, 1. We will refer to g0 as the intervention mechanism, which can be factorized in a treatment mechanism g01 and censoring mechanism g02 as follows:

In particular, the data might have been generated by a SMART, in which case g01 is known.

Let V(1) be a function of (L(0), A(0), L(1)), and let V(0) be a function of L(0). Let V = (V(0), V(1)). Consider dynamic treatment rules V(0) → dA(0)(V(0)) ∈ {0, 1} × {1} and (A(0), V(1)) → dA(1)(A(0), V(1)) ∈ {0, 1} × {1} for assigning treatment A(0) and A(1), respectively, where the rule for A(0) is only a function of V(0), and the rule for A(1) is only a function of (A(0), V(1)). Note that these rules are restricted to set the censoring indicators A2(j) = 1, j = 0, 1. Let be the set of all such rules. We assume that V(0) is a function of V(1) (i.e., observing V(1) includes observing V(0)), but in the theorem below we indicate an alternative assumption. For , we let

If we assume a structural equation model [7] for variables stating that

where the collection of functions f = (fL(0), fA(0), fL(1), fA(1)) is unspecified or partially specified, we can define counterfactuals Yd defined by the modified system in which the equations for A(0), A(1) are replaced by A(0) = dA(0)(V(0)) and A(1) = dA(1)(A(0), V(1)), respectively. Denote the distribution of these counter-factual quantities as P0,d, where we note that P0,d is implied by the collection of functions f and the joint distribution of exogeneous variables (UL(0), UA(0), UL(1), UA(1), UY). We can now define the causally optimal rule under P0,d as . If we assume a sequential randomization assumption stating that A(0) is independent of UL(1), UY, given L(0), and A(1) is independent of UY, given , A(0), then we can identify P0,d with observed data under the distribution P0 using the G-computation formula:

| (1) |

where p0,d is the density of P0,d and q0,L(0), q0,L(1), and q0,Y are the densities for Q0,L(0), Q0,L(1), and Q0,Y, respectively, where Q0,Y represents the distribution of Y given , . We assume that all densities above are absolutely continuous with respect to some dominating measure μ. We have a similar identifiability result/G-computation formula under the Neyman-Rubin causal model [8]. For the right censoring indicators A2(0) and A2(1), we note the parallel between the coarsening at random assumption and the sequential randomization assumption [49]. Thus here we have encoded our missingness assumptions in our causal assumptions.

More generally, for a distribution we can define the G-computation distribution Pd as the distribution with density

where qL(0), qL(1), and qY are the counterparts to q0,L(0), q0,L(1), and q0,Y, respectively, under P.

For the remainder of this article, if for a static or dynamic intervention d, we use notation Ld (or Yd, Od) we mean the random variable with the probability distribution Pd in (1) so that all of our quantities are statistical parameters. For example, the quantity EP0(Ya(0)a(1)|Va(0)(1)) defined in the next theorem denotes the conditional expectation of Ya(0)a(1), given Va(0)(1), under the probability distribution P0,a(0)a(1) (i.e., G-computation formula presented above for the static intervention (a(0), a(1)). In addition, if we write down these parameters for some Pd, we will automatically assume the positivity assumption at P required for the G-computation formula to be well defined. For that it will suffice to assume the following positivity assumption at P:

| (2) |

The strong positivity assumption will be defined as the above assumption, but where the 0 is replaced by a δ > 0.

We now define a statistical parameter representing the mean outcome Yd under Pd. For any rule , let

For a distribution P, define the V-optimal rule as

For simplicity, we will write d0 instead of dP0 for the V-optimal rule under P0. Define the parameter mapping . The first part of this article is concerned with inference for the parameter

Under our identifiability assumptions, d0 is equal to the causally optimal rule . Even if the sequential randomization assumption does not hold, the statistical parameter ψ0 represents a statistical parameter of interest in its own right. We will not concern ourselves with the sequential randomization assumption for the remainder of this paper.

The next theorem presents an explicit form of the V-optimal individualized treatment rule d0 as a function of P0.

Theorem 1. Suppose V(0) is a function of V(1). The V-optimal rule d0 can be represented as the following explicit parameter of P0:

where a(0) ∈ {0, 1} × {1}. If V(1) does not include V(0), but, for all (a(0), a(1)) ∈ {{0, 1} × {1}}2,

| (3) |

then the above expression for the V-optimal rule d0 is still true.

3 The efficient influence curve of the mean outcome under V-optimal rule

In this section we establish the pathwise differentiability of Ψ and give an explicit expression for the efficient influence curve [34, 50, 51]. Before presenting this result, we give the efficient influence curve for the parameter where Ψd(P) ≡ EPYd and the rule d = (dA(0), dA(1)) is treated as known. This influence curve has previously been presented in the literature [36, 41]. The parameter mapping Ψd has efficient influence curve:

where

| (4) |

Above (gA(0), gA(1)) is the intervention mechanism under the distribution P. We remind the reader that Yd has the G-computation distribution from (1) so that:

At times it will be convenient to write instead of , where Qd represents both of the conditional expectations in the definitions of and the marginal distribution of L(0) under P and g represents the intervention mechanism under P. We will denote these conditional expectations under P0 for a given rule d by . We will similarly at times denote D* (d, P) by D* (d, Qd, g).

Whenever D* (P) does not contain an argument for a rule d, this D* (P) refers to the efficient influence curve of the parameter mapping Ψ for which Ψ(P) = EPYdP, where the optimal rule dP under P is not treated as known. Not treating dP as known means that dP depends on the input distribution P in the mapping Ψ(P). The following theorem presents the efficient influence curve of Ψ at a distribution P. The main condition on this distribution P is that

| (5) |

where and are defined analogously to and in Theorem 1 with the expectations under P0 replaced by expectations under P. That is, we assume that each of the blip functions under P is nowhere zero with probability 1. Distributions that do not satisfy this assumption have been referred to as “exceptional laws” [32, 52]. These laws are indeed exceptional when one expects that treatment will have a beneficial or harmful effect in all V-strata of individuals. When one only expects that treatment will have an effect on outcome in some but not all strata of individuals then this assumption may be violated. We will make this assumption about P0 for all subsequent asymptotic linearity results about EP0Yd0, and we will assume a weaker but still not completely trivial assumption for the data adaptive target parameters in Sections 6 and 7.

Theorem 2. Suppose such that PrP(|Y| <M) = 1 for some M <∞ and the positivity assumption (2) and (5). Then the parameter is pathwise differentiable at P with canonical gradient given by

That is, D*(P) equals the efficient influence curve D*(dP, P) for the parameter ψd(P)≡EPYd at the V-optimal rule d = dP, where ψd treats d as given.

The above theorem is proved as Theorem 8 in van der Laan and Luedtke [48] so the proof is omitted here.

We will at times denote D*(P) by D*(Q, g), where Q represents QdP, along with portions of the likelihood which suffice to compute the V-optimal rule dP. We denote dP by dQ when convenient. We explore which parts of the likelihood suffice to compute the V-optimal rule in our companion paper, though Theorem 1 shows that and suffice for d0 (and analogous functions suffice for a more general dP). We have the following property of the efficient influence curve, which will provide a fundamental ingredient in the analysis of the TMLE presented in the next section.

Theorem 3. Let dQ be the V-optimal rule corresponding with Q. For any Q, g, we have

where for all

ψd(P) = EPYd is the statistical target parameter that treats d as known, and is the efficient influence curve of ψd at P0 as given in Theorem 2. In addition,

From the study of the statistical target parameter ψd in van der Laan and Gruber [41], we know that , where R1d is a closed form second-order term involving integrals of differences times differences g − g0.

The following lemma bounds R2. We note that this lemma, which concerns how well we can estimate d0 rather than how well we can make inference about EP0Yd0, does not require condition (5) to hold. We showed in Theorem 1 that knowing the blip functions and suffices to define the optimal rule d0. For general Q, we will let and represent the blip functions under this parameter mapping.

Lemma 1. Let R2 be as in Theorem 3. Let P0,(0,1) represent the static intervention-specific G-computation distribution where treatment (0, 1) is given at the first time point. Suppose there exist some β1, β2 > 1 such that:

| (6) |

where the expression in each expectation is taken to be 0 when the indicator is 0. Fix p ∈ (1, ∞] and define h : (1, ∞] × (1, ∞) as the function for which when p<∞ and h(p, β) = β + 1 otherwise. Then:

where ∥·∥p,P denotes the Lp,P norm for the distribution P and K1, K2 ≥ 0 are finite constants that respectively rely on p, P0, β1 and p, P0,(0,1), β2.

The conditions in (6) are moment bounds which ensure that and do not put too much mass around zero. To get the tightest bound, we should always choose β1, β2 to be as large as possible. We remind the reader that convergence in Lp,P implies convergence in Lq,P for all distributions P and 1 ≤ q ≤ p ≤ ∞. Hence there is a trade-off between the chosen bounding norm, Lp,P, and the rate we need to obtain with respect to that norm so that the term can be expected to be of order n−1/2. See Table 1 for some examples of rates of convergence that suffice to give R2A(0) = oP0 (n−1/2).

Table 1.

Convergence rates of estimators of which suffice for R2A(0) to be oP0(n−1/2) according to Lemma 1. The higher the moments of that are finite, the slower the estimator needs to converge. It is of course preferable to have an estimator which converges according to the Po essential supremum than just in L2,P0 but whether or not there is convergence in L∞,P0 depends on the estimator used and the underlying distribution P0.

| p | β 1 | Sufficient Lp,P0 convergence rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | oP0 (n−3/8) |

| 2 | oP0 (n−1/3) | |

| β1 large | oP0 (n−(1/4+ε))for small ε>0 | |

| 4 | 1 | oP0 (n−5/16) |

| 2 | oP0 (n−1/4) | |

| β1 large | oP0 (n−(1/8+ε))for small ε>0 | |

| ∞ | 1 | oP0 (n−1/4) |

| 2 | oP0 (n−1/6) | |

| β1 large |

|

Using the upper bound on and applying Cauchy-Schwarz inequality to eq. (15) in the proof of the lemma shows that:

Hence R2A(0) = oP0 (n−1/2) without any moment condition when , which occurs when one has correctly specified a parametric model for . In general it is unlikely that one can correctly specify a parametric model for . In these cases, Lemma 1 shows that the term R2A(0) will still be oP0 (n−1/2) if a moment condition holds and is estimated at a sufficient rate. The analogue holds for .

The bounds given in Lemma 1 are loose. It is not in general necessary to estimate the blip functions and correctly, only their signs. As an extreme example of the looseness of the bounds, one can have that as n → ∞ and still have that R2A(0)(Q, Qn) = 0 for all n. Nonetheless, these bounds give interpretable sufficient conditions under which the term R2 converges faster than a root-n rate. We consider methods that do not directly estimate the blip functions in our companion paper.

4 TMLE of the mean outcome under V-optimal rule

Throughout this and the next section we assume that condition (5) holds at P0. Our proposed TMLE is to first estimate the optimal rule d0, giving us an estimated rule dn(A(0),V) = dn,A(0)(V(0)),dn,A(1)(A(0),V(1)), and subsequently apply the TMLE of EYd for a fixed rule d at dn = dn as presented in van der Laan and Gruber [41]. This TMLE is an analogue of the double robust estimating equation method presented in Bang and Robins [36]: see also Petersen et al. [40] for a generalization of the TMLE to marginal structural models for dynamic treatments. In a companion paper we describe a data adaptive estimator of d0. In this paper we take dn as given. We review the TMLE for ψd(P0) = EP0Yd at a fixed rule d in “TMLE of the mean outcome under a given rule” in Appendix B. Observations which are only partially observed due to right censoring do not cause a problem for the TMLE. In particular, the TMLE only uses individuals who are not right censored at the first or second time point to obtain initial estimates of EP0[Yd|A(0) = dA(0)(V(0)),L(0)] and in (4), respectively. See the appendix for details.

Here we note some of the key properties of the TMLE. Let consist of the empirical distribution QL(0),n of L(0), a regression function that estimates EP0[Yd|L(0)], and a regression function

that estimates , where we note that v is a function of . In the appendix we describe our proposed algorithm to get the estimates in . The proposed TMLE for ψ0 = EP0Yd0 is given by

where we have applied the TMLE in the appendix to the case where d = dn, treating dn as known. Note that is a plug-in estimator in that it is obtained by plugging into the parameter mapping Qd ↦ ψd(Qd) for d = dn. We expect our plug-in estimator to give reasonable estimates in finite samples because it naturally respects the constraints of our model. In the next section we show that this estimator also enjoys many desirable asymptotic properties.

Recall that D*(d, Qd, g) is the efficient influence curve for the target parameter EP0Yd which treats d as fixed, and Theorem 2 showed that is the efficient influence curve of the target parameter EYd0 where d0 is the V-optimal rule. The TMLE described in the appendix solves the efficient influence curve estimating equation:

| (7) |

Further, one can show using standard M-estimator analysis that the targeted proposed in the appendix maintains the same rate of convergence as the initial estimator under very mild conditions. We do not concern ourselves with these conditions in this paper, and will instead state all conditions directly in terms of . The above will be a key ingredient in proving the asymptotic linearity of the TMLE for ψ0 = EP0Yd0.

5 Asymptotic efficiency of the TMLE of the mean outcome under the V-optimal rule

We now wish to analyze the TMLE of . We first give a representation that will allow us to prove the asymptotic linearity of the TMLE under conditions. The result allows to be misspecified, even though the intervention mechanism g0 and the rule dn are assumed to be consistent for g0 and d0, respectively.

Theorem 4. Assume Y ∈ [0,1], the strong positivity assumption, condition (5) at p0, falls in a P0-Donsker class with probability tending to 1, converges to zero in probability for some Qd0, and

where R2 is defined in Theorem 3 and an upper bound is established in Lemma 1. Then

| (8) |

where R1d is defined in Theorem 3.

The proof of the above theorem, which is given in the appendix, makes use of the fact that the TMLE satisfies (7). We now give two sets of conditions which control the remainder term R1dn in (8) to prove the asymptotic linearity of the TMLE. The first result is an immediate consequence of the fact that whenever gn = g0.

Corollary 1. Suppose the conditions of Theorem 4 further suppose that gn = g0 (i.e., RCT). Then:

That is, is asymptotically linear with influence curve D* (d0, Qd0, g0).

The next corollary is more general in that it applies to situations where the intervention mechanism g0 is estimated from the data. The above result emerges as a special case.

Corollary 2. Suppose all of the conditions of Theorem 4 hold, and that

for some Qdn. In addition, we assume the following asymptotic linearity condition on a smooth functional of gn:

| (9) |

for some function . Then,

| (10) |

If it is also know that gn is an MLE of g0 according to a correctly specified model G for g0 with tangent space Tg(P0) at P0, then (9) holds with

| (11) |

where Π(·Tg(P0)) denotes the projection operator onto in the Hilbert space .

Equation (11) is a corollary of Theorem 2.3 of van der Laan and Robins [34]. The rest of the theorem is the result of a simple rearrangement of terms, so the proof is omitted.

Condition (9) is trivially satisfied in a randomized clinical trial without missingness, where we can take gn = g0 and thus Dg(P0) is the constant function 0. Nonetheless, (11) suggests that it would be better to estimate g0 using a parametric model that contains the true (known) intervention mechanism. For example, at each time point one may use a main terms linear logistic regression with treatment and covariate histories as predictors. If consistently estimates , then D* (d0, Qd0, g0) is orthogonal to Tg(P0) and hence the projection in (11) is the constant function 0. Otherwise the projection will decrease the variance of without affecting asymptotic bias, thereby increasing the asymptotic efficiency of the estimator. One can then use an empirical estimate of the variance of D*(d0, Qd0, g0) to get asymptotically conservative confidence intervals for ψ0.

5.1 Asymptotic linearity of TMLE in a SMART setting

Suppose the data is generated by a sequential RCT and there is no missingness so that g0 is known. Further suppose that (5) holds at P0, that is, that treating at each time point has either a positive or negative effect with probability 1, regardless of the choice of the regimen at earlier time points. In addition, assume that V(0) and V(1) are both univariate scores, and assume condition (3) so that the optimal rule d0,A(1) based on (A(0), V(0), V(1)) is the same as the optimal rule d0,A(1) based on A(0), V(1): for example, V(1) is the same score as V(0) but measured at the next time point, so that it is reasonable to assume that an effect of V(0) on Y will be fully blocked by V(1). Suppose we want to use the data of the RCT to learn the V-optimal rule d0 and provide statistical inference for EP0Yd0. Further suppose that the moment conditions in Lemma 1 hold with β1 = β2 = 2. Since both V(0) and V(1) are one-dimensional, using kernel smoothers or sieve-based estimation to generate a library of candidate estimators for the sequential loss-based super-learner of the blip functions () described in our companion paper, we can obtain an estimator of that converges in L2 at a rate such as n−2/5 under the assumption that are continuously differentiable with a uniformly bounded derivative, or at a better rate under additional smoothness assumptions. As a consequence, in this case R2(Qn, Q0) = OP0 (n−3/5) = OPo(n−1/2) by Lemma 1. As a consequence, all conditions of Theorem 4 hold, and it follows that the proposed TMLE is asymptotically linear with influence curve D* (d0, Qd0, g0), where Qd0 is the possibly misspecified limit of Qdn* in the TMLE. To conclude, sequential RCTs allow us to learn V-optimal rules at adaptive optimal rates of convergence, and allow valid asymptotic statistical inference for EP0 Yd0. If V(j) is higher dimensional, then one will have to rely on enough smoothness assumptions on the blip functions and/or moment conditions on and from Lemma 1 in order to guarantee that .

If there is right censoring, then g0 = g01g02 factors in a treatment mechanism g01 and censoring mechanism g02, where g01 is known, but g02 is typically not known. Having a lot of knowledge about how censoring depends on the observed past might make it possible to obtain a good estimator of g02. In that case, the above conclusions still apply, but one now estimates the nuisance parameters of the loss function (e.g., one uses a double robust loss function in which g02 is replaced by an estimator, see our companion paper).

5.2 Statistical inference

Suppose one wishes to estimate the mean outcome under the optimal rule EP0 Yd0 and that (5) holds. Above we developed the TMLE for EP0 Yd0. By Corollary 1, if gn = g0 is known, this TMLE of ψ0 is asymptotically linear with influence curve IC(P0) = D* (d0, Qd0, g0). If gn is an MLE according to a model with tangent space Tg(P0), then the TMLE is asymptotically linear with influence curve

so that one could use IC(P0) as a conservative influence curve. Let ICn be an estimator of this influence curve IC(P0) obtained by plugging in the available estimates of its unknown components. The asymptotic variance of the TMLE of ψ0 can now be (conservatively) estimated with

An asymptotic 95% confidence interval for ψ0 is given by .

6 Statistical inference for mean outcome under data adaptively determined dynamic treatment

Let be an estimator that maps an empirical distribution into an individualized treatment rule. See our companion paper for examples of possible estimators . Let be the estimated rule. Up until now we have been concerned with statistical inference for EP0 Yd0, where d0 is the unknown V-optimal rule while dn is a best estimator of this rule. As a consequence, statistical inference for EP0 Yd0 based on the TMLE relied on consistency of dn to d0, but also relied on the rate of convergence at which dn converges to d0, that is, . In this section we present statistical inference for the data adaptive target parameter

That is, we construct an estimator of and a confidence interval so that

where is a consistent estimator of the standard error of . Note that in this definition of the confidence interval the target parameter is itself also a random variable through the data Pn.

We do not assume that (5) holds in this section, but we do implicitly make the weaker assumption that dn → d1 for some in assumption (12) of Theorem 5. Statistical inference will be based on the same TMLE of ψd(P0) at d = dn, and our variance estimator will also be the same, but since the target is not ψd0 (P0) but ψdn(P0), there will be no need for dn to even be consistent for d0, let alone converge at a particular rate. As a consequence, this approach is particularly appropriate in cases where V is high dimensional so that it is not reasonable to expect that dn converges to d0 at the required rate. Another motivation for this data adaptive target parameter is that, even when statistical inference for EP0 Yd0 is feasible, one might be interested in statistical inference for the mean outcome under the concretely available rule dn instead of under the unknown rule d0.

As shown in the proof of Theorem 3, . Further, , which yields

This relation is key to the proof of the following theorem, which is analogous to Theorem 4. Note crucially that the theorem does not have any conditions on the remainder term R2, nor does it require that dn converge to the optimal rule d0.

Theorem 5. Assume Y ∈ [0, 1]. Let with probability tending to 1, and assume the strong positivity assumption. Let ψ0n = ψdn(P0) = EP0 Yd|d=dn be the data adaptive target parameter of interest. Let R1d be as defined in Theorem 3.

Assume falls in a P0 -Donsker class with probability tending to 1,

| (12) |

for some and Qd1. Then,

If gn = g0 (i.e., RCT), then , so that is asymptotically linear with influence curve D* (d1, Q, g0).

The proof of the above theorem is nearly identical to the proof of Theorem 4 so is omitted. For general gn, under an analogous second-order term condition to the one assumed in Corollary 1. As in Corollary 2, the asymptotic efficiency may improve (and will not worsen) when a known intervention mechanism is fit using a correctly specified parametric model. See Theorem 11 in our online technical report for details [47].

7 Statistical inference for the average of sample-split specific mean counterfactual outcomes under data adaptively determined dynamic treatments

Again let be an estimator that maps an empirical distribution into an individualized treatment rule. Let Bn ∈ {0, 1}n denote a random vector for a cross-validation split, and for a split Bn, let be the empirical distribution of the training sample {i : Bn(i) = 0} and is the empirical distribution of the validation sample {i : Bn(i) = 1}. Consider a J-fold cross-validation scheme. In J-fold cross-validation, the data is split into J mutually exclusive and exhaustive sets of size approximately n/J uniformly at random. Each set is then used as the validation set once, with the union of all other sets serving as the training set. With probability 1/J, Bn has value 1 in all indices in validation set j ∈ {1; …, J} and 0 for all indices not corresponding to training set j.

In this section, we present a method that provides an estimator and statistical inference for the data adaptive target parameter

Note that is different from the data adaptive target parameter ψ0n presented in the previous section. In particular, this target parameter is defined as the average of data adaptive parameters, where the data adaptive parameters are learned from the training samples of size approximately n/J. In the previous section, the data adaptive target parameter was defined as the mean outcome under the rule dn which was estimated on the entire data set. Again the target parameter is a random quantity that relies on the sample of size n.

One applies the estimator to each of the J training samples, giving a target parameter value , and our target parameter is defined as the average across these J target parameters. Below we present a CV-TMLE of this data adaptive target parameter . As in the previous section, we will be able to establish statistical inference for our estimate without requiring that the estimated rules converge to d0, nor any rate condition on the estimated rules. Unlike the asymptotic linearity results in all previous sections, the results in this section do not rely on an empirical process condition (i.e., Donsker class condition). That means we obtain valid asymptotic statistical inference under essentially no conditions in a sequential RCT, even when dn is a highly data adaptive estimator of a V-optimal rule for a possibly high dimensional V. Under a consistency and rate condition (but no empirical process condition) on dn, we also get inference for EP0Yd0.

The next subsection defines the general CV-TMLE for data adaptive target parameters. We subsequently present an asymptotic linearity theorem allowing us to construct asymptotic 95% confidence intervals.

7.1 General description of CV-TMLE

Here we give a general overview of the CV-TMLE procedure. In “CV-TMLE of the mean outcome under data adaptive V-optimal rule” in Appendix B we present a particular CV-TMLE which satisfies all of the properties described in this section. Denote the realizations of Bn with j = 1, …, J, and let for some estimator of the optimal rule . Let

represent an initial estimate of based on the training sample j. Similarly, let l(0) ↦ Enj[Ydnj |L(0) = l(0)] represent an initial estimate of EP0[Ydnj |L(0)] based on the training sample j. Finally, let QL(0),nj represent the empirical distribution of L(0) in validation sample j. We then fluctuate these three regression functions using the following submodels:

where these submodels rely on an estimate gnj of g0 based on training sample j and are such that:

Let represent the parameter mapping that gives the three regression functions above fluctuated by ε≡(ε0, ε1, ε2). For a fixed ε, only relies on through the empirical distribution of L(0) in validation sample j. Let ϕ be a valid loss function for so that , and let ϕ and the submodels above satisfy

where 〈f〉 = {Σj βjfj : β} denotes the linear space spanned by the components of f. We choose εn to minimize over . We then define the targeted estimate of . We note that maintains the rate of convergence of Qnj under mild conditions that are standard to M-estimator analysis. The key property that we need from the εn and the corresponding update is that it (approximately) solves the cross-validated empirical mean of the efficient influence curve:

| (13) |

The CV-TMLE implementation presented in the appendix satisfies this equation with replaced by the 0. The proposed estimator of is given by

In the current literature we have referred to this estimator as the CV-TMLE [53–56]. We give a concrete CV-TMLE algorithm for in “CV-TMLE of the mean outcome under data adaptive V-optimal rule” in Appendix B, but note that other CV-TMLE algorithms can be derived using the approach in this section for different choices of loss function ϕ and submodels.

7.2 Statistical inference based on the CV-TMLE

We now proceed with the analysis of this CV-TMLE of . We first give a representation theorem for the CV-TMLE that is analogous to Theorem 5.

Theorem 6. Let gnj and dnj represent estimates of g0 and d0 based on training sample j. Let represent a targeted estimate of as presented in Section 7.1 so that satisfies (13). Let R1d be as in Theorem 3. Further suppose that the supremum norm of maxj is bounded by some M <∞ with probability tending to 1, and that

for some and possibly misspecified Qd1 and g. Then:

Note that d1 in the above theorem need not be the same as the optimal rule d0, though later we will discuss the desirable special case where d1 = d0. The above theorem also does not require that g0 is known, or even that the limit of our intervention mechanisms g is equal to g0. Nonetheless, we get the following asymptotic linearity result when g = g0 and gnj satisfies an asymptotic linearity condition on a smooth functional of gnj.

Corollary 3. Suppose the conditions from Theorem 6 hold with g = g0. Further suppose that:

for some Qdnj and that:

| (14) |

We can conclude that:

The proof of the above result is just a rearrangement of terms so is omitted. Consider our setting. Suppose g0 is known so we can have that gnj = g0 for all j. Consider the estimator

of the asymptotic variance of the CV-TMLE . An asymptotic 95% confidence interval for is given by . This same variance estimator and confidence interval can be used for the case that g0 is not known and each gnj is an MLE of g0 according to some model. In that case, it is an asymptotically conservative confidence interval (analogous to eq. (11) applied to Corollary 3).

Now consider the case where d1 from the above theorem is equal to the optimal rule d0 and condition (5) holds. For simplicity, also assume that g0 is known and gnj = g0. Then R1dnj is equal to 0 for all j, so Theorem 6 shows that the CV-TMLE for is asymptotically linear with influence curve . If

is second order, that is, oP0 (n−1/2), where Qnj is analogous to Qn but only estimated on the training sample j, then the CV-TMLE is consistent and asymptotically normal estimator of the mean outcome under the optimal rule. If , then the CV-TMLE is also asymptotically efficient among all regular asymptotically linear estimators. One can apply bounds like those in Lemma 1 for each of the J terms above to understand the behavior of . Note crucially that this result does not rely on the restrictive empirical process conditions used in the previous sections, although it relies on a consistency and rate condition for asymptotic linearity with respect to the non-data adaptive parameter EP0Yd0.

8 Simulation methods

We start by presenting two single time point simulations. In earlier technical reports we directly describe the single time point problem [47, 48]. Here, we instead note that a single time point optimal treatment is a special case of a two time point treatment when only the second treatment is of interest. In particular, we can see this by taking L(0) = V(0) = ∅, estimating without any dependence on a(0), and correctly estimating with the constant function zero. We note that, in this one time point formulation, we do not need (5) to hold for , so it may be more natural to view the single time point problem directly and use the single time point pathwise differentiability result in Theorem 2 of van der Laan and Luedtke [48]. We can then let I(A(0) = dn,A(0)(V(0))) = 1 for all A(0), V(0) wherever the indicator appears in our calculations. Because the first time point is not of interest, we only describe the second time point treatment mechanism for this simulation. We refer the interested reader to the earlier technical report for a thorough discussion of the single time point case. We then present a two time point data generating distribution to show the effectiveness of our proposed method in the longitudinal setting.

8.1 Data

8.1.1 Single time point

We simulate 1,000 data sets of 1,000 observations from an RCT without missingness. We have that:

where Y is a Bernoulli random variable and H is an unobserved Bern(1/2) variable independent of , . The above distribution was selected so that the mean outcomes under static treatments (treating everyone or no one at the second time point) have approximately the same mean outcome of 0.464.

We consider two choices for V(1). For the first we consider V(1) = L3(1), and for the second we consider V(1) to be the entire covariate history . We have shown via Monte Carlo simulation that the optimal rule has mean outcome EP0Yd0 ≈ 0.536 when V(1) = L3(1) and the optimal rule has mean outcome EP0Yd0 ≈ 0.563 when V(1) = (L1(1), L2(1), L3(1), L4(1)). One can verify that the blip function at the second time point is nonzero with probability 1 for both choices of V(1).

8.1.2 Two time point

We again simulate 1,000 data sets of 1,000 observations from an RCT without missingness. The observed variables have the following distribution:

where

Note that is contained in the unit interval by the bounds on and so that Y is indeed a valid Bernoulli random variable. We will let V(0) = L(0) and . One can verify that (5) is satisfied for this choice of V.

Static treatments yield mean outcomes EP0Y(0,1),(0,1) = 0.400, EP0Y(0,1),(1,1) ≈ 0.395, EP0Y(1,1),(0,1) ≈ 0.361, and EP0Y(1,1),(1,1) ≈ 0.411. The true optimal treatment has mean outcome EP0Yd0 ≈ 0.485.

8.2 Optimal rule estimation methods

For now suppose we have estimators of the optimal rule with reasonable convergence properties, by which we mean that the true mean outcome under the fitted rule is close to the mean outcome under the optimal rule. In our companion paper in this volume we describe these estimators and show precisely how close these estimators come to achieving the optimal mean outcome. Here we note that our estimation algorithms correspond to using the full candidate library of weighted classification and blip function-based estimators proposed in table 2 of our companion paper, with the weighted log loss function used to determine the convex combination of candidates. We provide oracle inequalities for this estimator in our companion paper, and argue that it represents a powerful approach to data adaptively estimate the optimal rule without over- or underfitting the data. For a sample size n, we denote the rule estimated on the whole sample by dn, and the rule estimated on training sample j by dnj.

8.3 Inference procedures

We use four procedures to estimate the mean outcome under the fitted rule. All inference procedures rely on the intervention mechanism g0. We always estimate the intervention mechanism with the true mechanism g0, as one may do in an RCT without missingness. We do not consider efficiency gains resulting from estimating the known treatment mechanism here.

The first method uses the TMLE described in “TMLE of the mean outcome under a given rule” in Appendix B. The second method uses the analogous estimating equation approach that uses the double robust inverse probability of censoring weighted (DR-IPCW) estimating equation implied by , where represents the unfluctuated initial estimates of . See van der Laan and Robins [34] for a general outline of such an estimating equation approach. This approach is valid whenever the TMLE is valid. We also use the CV-TMLE described in “CV-TMLE of the mean outcome under data adaptive V-optimal rule” in Appendix B, where we use a 10-fold cross-validation scheme. Finally, we use the CV-DR-IPCW cross-validated estimating equation implied by , where represents the unfluctuated initial estimates of . This approach is valid whenever the CV-TMLE is valid.

All inference procedures also rely on an estimate of for some estimated d. For the two time point case, we use the empirical distribution of L(0) to estimate the marginal distribution of L(0). We compare plugging in both of the true values of and EP0 [Yd|L(0, A(0) = dA(0)(V(0)) as initial estimates with plugging in the incorrectly specified constant function 1/2 as initial estimates.

For the single time point case, we compare plugging in the true value of with the incorrectly specified constant function 1/2. We always estimate EP0 [Yd|L(0), A(0) = dA(0)(V(0))] by averaging

over the empirical distribution of L(1) from the entire sample for non-cross-validated methods, and from the training sample for cross-validated methods. The empirical distribution of L(0) will not play a role for the single time point case because L(0) = ∅.

The procedures used to estimate the optimal rule rely on similar means, and we supply these estimation procedures with the incorrect value 1/2 for these conditional means whenever we supply the inference procedures with the incorrect values of the corresponding conditional means, and with the correct values of the conditional means whenever we supply the inference procedures with the corresponding correct values.

The simulation was implemented in R [57]. The code used to run the simulations is available upon request. We are currently looking to implement the methods in this paper and the companion paper in an R package.

8.4 Evaluating performance

We use the coverage of asymptotic 95% confidence intervals to evaluate the performance of the various methods. As we establish in the earlier parts of this paper, each inference approach yields two interesting target parameters with respect to which we can compute coverage. All approaches give asymptotically valid inference for the mean outcome under the optimal rule under conditions, and thus the coverage with respect to this parameter is assessed across all methods.

The TMLE and DR-IPCW estimating equation-based approaches also estimate the data adaptive target parameter ψ0n as presented in Section 6. Given a fitted rule dn, we approximate the expected value in this parameter definition using 106 Monte Carlo simulations for the single time point case and 5 × 105 Monte Carlo simulations for the two time point case. We then assess confidence interval coverage with respect to this approximation.

The CV-TMLE and cross-validated DR-IPCW estimating equation approaches estimate the data adaptive target parameter as presented in Section 7. Given the ten rules estimated on each of the training sets, the expectation over the sample split random variable Bn becomes an average over ten target parameters, one for each estimated rule. Again we estimate the expected value of P0 using 106 Monte Carlo simulations for each of the ten target parameters in the single time point case, and 5 × 105 Monte Carlo simulations in the two time point case.

9 Simulation results

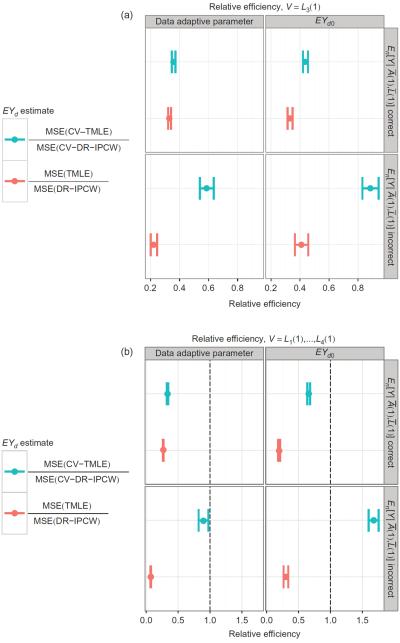

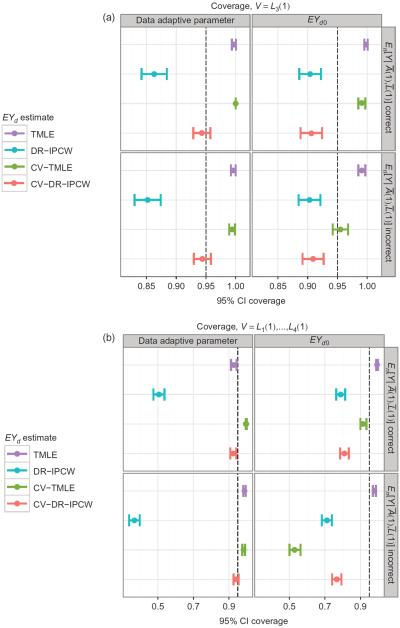

Figure 1 shows that the (CV-)TMLE is more efficient than the (CV-)DR-IPCW estimating equation methods in our single time point simulation, except for the cross-validated methods when V = L1(1),…, L4(1) and the regressions are misspecified. Note that the MSEs relative to EP0 Yd0 are the typical EP0(ψn − ψ0)2 for an estimate ψn, while the MSEs relative to the data adaptive parameter are the slightly less typical EP0(ψn − ψ0n)2 for the TMLE and DR-IPCW, and for the cross-validated methods. That is, the target parameters vary for each of the 1,000 data sets considered. We also confirmed that, as is typical in missing data problems, the methods in which the conditional means were correctly specified were more efficient than the methods in which the conditional means are incorrectly specified. Figure 2 shows that the (CV-)TMLE in general has better coverage than the (CV-)DR-IPCW estimating equation approaches in our single time point simulation, with the only exception being the CV-TMLE for EP0 Yd0 when the regressions are misspecified and V = L1(1),…, L4(1).

Figure 1.

Relative efficiency of TMLE and DR-IPCW methods compared to both EP0Yd0 and the data adaptive parameter EP0(ψn – ψ0n)2 for the TMLE and DR-IPCW, and for the cross-validated methods. Results are provided both for the cases where the estimate of is correctly specified and the case where this estimate is incorrectly specified with the constant function 1/2. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals to account for uncertainty from the finite number of Monte Carlo draws in our simulation. (a) V=L1(1), (b) V=L1(1), …, L4(1).

Figure 2.

Coverage of 95% confidence intervals from the TMLE and DR-IPCW methods with respect to both EP0 Yd0 and the data adaptive parameter ψ0n for the TMLE and DR-IPCW and for the cross-validated methods. Results are provided both for the cases where the estimate of is correctly specified and the case where this estimate is incorrectly specified with the constant function 1/2. The (CV-)TMLE outperforms the (CV-)DR-IPCW estimating equation approach for almost all settings. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals to account for uncertainty from the finite number of Monte Carlo draws in our simulation. (a) V=L1(1), (b) V=L1(1), …, L4(1).

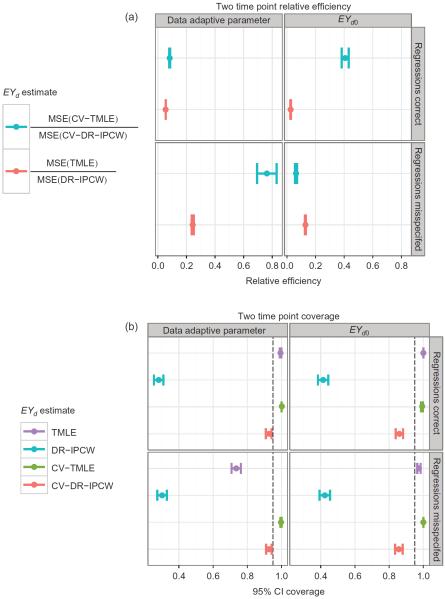

Figure 3a shows that the (CV-)TMLE is always more efficient than the (CV-)DR-IPCW estimating equation methods for our two time point simulation. Figure 3b shows that this increased efficiency does not come at the expense of coverage: the (CV-)TMLE always has better coverage than the (CV-) DR-IPCW estimators in our two time point simulation. In general, we see that the cross-validated methods always achieve approximately 95% coverage for the data adaptive parameter. This is to be expected because the cross-validated methods only learn the optimal rule on validation sets, and thus avoid finite sample bias when the conditional means of the outcome are averaged over the validation samples.

Figure 3.

(a) Relative efficiency of TMLE and DR-IPCW methods compared to both EP0 Yd0 and the data adaptive parameter EP0 (ψn – ψ0n)2 for the TMLE and DR-IPCW, and for the cross-validated methods. (b) Coverage of 95% confidence intervals from the TMLE and DR-IPCW methods with respect to both EP0 Yd0 and the data adaptive parameter ψ0n for the TMLE and DR-IPCW and for the cross-validated methods. Both (a) and (b) give results both for the cases where the estimates of and EP0[Ydn|L(0)] are correctly specified and the case where these estimates are incorrectly specified with the constant function 1/2. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals to account for uncertainty from the finite number of Monte Carlo draws in our simulation.

It may at first be surprising that the TMLE outperforms the DR-IPCW estimating equation method in a randomized clinical trial, especially given that the CV-TMLE and CV-DR-IPCW achieve similar coverage. In Appendix C we give intuition as to why this may be the case in a single time point randomized clinical trial. In short, this difference in coverage appears to occur because our proposed TMLE only fluctuates the conditional means for individuals who received the fitted treatment, thereby reducing finite sample bias that may result from estimating the optimal rule on the same sample that is used to estimate the mean outcome under this fitted rule.

We also looked at the average confidence interval width across Monte Carlo simulations for each method and simulation setting. For a given simulation setting, all four estimation methods gave approximately the same (±0:002) average confidence interval width: 0.08 for both single time point simulations, 0.12 for the multiple time point simulation. These average widths show that we can get informatively small confidence intervals from our relatively small sample size of 1,000 individuals. Unlike Figures 1 and 3a, these values should not be used to gauge the efficiency of the proposed estimators since they do not take the true parameter value into account.

10 Discussion

This article investigated semiparametric statistical inference for the mean outcome under the V-optimal rule and statistical inference for the data adaptive target parameter defined as the mean outcome under a data adaptively determined V-optimal rule (treating the latter as given).

We proved a surprising and useful result stating that the mean outcome under the V-optimal rule is represented by a statistical parameter whose pathwise derivative is identical to what it would have been if the unknown rule had been treated as known, under the condition that the data is generated by a non-exceptional law [52]. As a consequence, the efficient influence curve is immediately known, and any of the efficient estimators for the mean outcome under a given rule can be applied at the estimated rule. In particular, we demonstrate a TMLE, and present asymptotic linearity results. However, the dependence of the statistical target parameter on the unknown rule affects the second-order terms of the TMLE, and, as a consequence, the asymptotic linearity of the TMLE requires that a second-order difference between the estimated rule and the V-optimal rule converges to zero at a rate faster than . We show that this can be expected to hold for rules that are only a function of one continuous score (such as a biomarker), but when V is higher dimensional, only strong smoothness assumptions will guarantee this, so that, even in an RCT, we cannot be guaranteed valid statistical inference for such V-optimal rules.

Therefore, we proceeded to pursue statistical inference for so-called data adaptive target parameters. Specifically, we presented statistical inference for the mean outcome under the dynamic treatment regime we fitted based on the data. We showed that statistical inference for this data adaptive target parameter does not rely on the convergence rate of our estimated rule to the optimal rule, and in fact only requires that the data adaptively fitted rule converges to some (possibly suboptimal) fixed rule. However, even in a sequential RCT, the asymptotic linearity theorem still relies on an empirical process condition that limits the data adaptivity of the estimator of the rule. So, even though the assumptions are much weaker, they can still cause problems in finite samples when V is high dimensional, and possibly even asymptotically.

Therefore, we proceeded with the average of sample split specific target parameters, as in general proposed by van der Laan et al. [46], where we show that statistical inference can now avoid the empirical process condition. Specifically, our data adaptive target parameter is now defined as an average across J sample splits in training and validation sample of the mean outcome under the dynamic treatment fitted on the training sample. We presented CV-TMLE of this data adaptive target parameter, and we established an asymptotic linearity theorem that does not require that the estimated rule is consistent for the optimal rule, let alone at a particular rate. The CV-TMLE also does not require the empirical process condition. As a consequence, in a sequential RCT, this method provides valid asymptotic statistical inference without any conditions, beyond the requirement that the estimated rule converges to some (possibly suboptimal) fixed rule.

We supported our theoretical findings with simulations, both in the single and two time point settings. Our simulations supported our claim that it is easier to have good coverage of the proposed data adaptive target parameters than the mean outcome under the optimal rule, though the results for this harder mean outcome under the optimal rule parameter were also promising. In future work we hope to apply these methods to actual data sets of interest, generated by observational controlled trial as well as RCTs.

It might also be of interest to propose working models for the mean outcome EP0 [Yd0 |S] under the optimal rule, conditional on some baseline covariates S ⊂ W. This is now a function of S, but we would define the target parameter of interest as a projection of this true underlying function on the working model. It would now be of interest to develop TMLE for this finite dimensional pathwise differentiable parameter, and we presume that similar results as we found here might appear. Such parameters provide information about how the mean outcome under the optimal rule are affected by certain baseline characteristics.

Drawing inferences concerning optimal treatment strategies is an important topic that will hopefully help guide future health policy decisions. We believe that working with a large semiparametric model is desirable because it helps to ensure that the projected health benefits from implementing an estimated treatment strategy are not due to bias from a misspecified model. The TMLEs presented in this article have many desirable statistical properties and represent one way to get estimates and make inference in this large model. We look forward to future advances in statistical inference for parameters that involve optimal dynamic treatment regimes.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by an NIH grant R01 AI074345-06. AL was supported by the Department of Defense (DoD) through the National Defense Science & Engineering Graduate Fellowship (NDSEG) program. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and Erica Moodie for their invaluable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper. The authors would also like to thank Oleg Sofrygin for valuable discussions.

Funding: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, (Grant / Award Number: `R01 AI074345-06')

Appendix A

Proofs

Proof of Theorem 1. Let Vd = (V(0), Vd(1)). For a rule in , we have

For each value of a(0), Va(0) = (V(0), Va(0)(1)) and dA(0)(V(0)), the inner conditional expectation is maximized over dA(1)(a(0), Va(0)(1)) by d0,A(1) as presented in the theorem, where we used that V(1) includes V(0). This proves that d0,A(1) is indeed the optimal rule for assignment of A(1). Suppose now that V(1) does not include V(0), but the stated assumption holds. Then the optimal rule d0,A(1) that is restricted to be a function of (V(0), V(1), A(0)) is given by , where

However, by assumption, the latter function only depends on (a(0), v(0), v(1)) through (a(0), v(1)), and equals . Thus, we now still have that , and, in fact, it is now also an optimal rule among the larger class of rules that are allowed to use V(0) as well.

Given we found d0,A(1), it remains to determine the rule d0,A(0) that maximizes

where we used the iterative conditional expectation rule, taking the conditional expectation of Va(0), given V(0). This last expression is maximized over dA(0) by d0,A(0) as presented in the theorem. This completes the proof.

The following lemma will be useful for proving Theorem 2.

Lemma 1. Recall the definitions of and in Theorem 1. We can represent Ψ(P0) = EP0 Yd0 as follows:

where V(0,1)(1) is drawn under the G-computation distribution for which treatment (0, 1) is given at the first time point.

Proof of Lemma A.1. For a point treatment data structure O = (L(0), A(0), Y) and binary treatment A(0), we have for a rule with . This identity is applied twice in the following derivation:

Proof of Theorem 3. By the definition of R1d we have

Proof of Lemma 1. Below we omit the dependence of dQ,A(0), d0,A(0), , and on V(0):

The first term in the final equality is always 0 because dQ,A(0) = d0,A(0) whenever the indicator is 1. In the second term, dQ,A(0) ≠ d0,A(0) whenever the indicator is 1, so:

| (15) |

where the final inequality holds by Hölder's inequality. The above also holds when the limit is taken as p ≠ ∞, yielding the essential supremum result. The result for R2A(1) follows by the same argument.

Proof of Theorem 4. By Theorem 3, we have

where . Combining this with the fact that has empirical mean 0 yields

The Donsker condition and the mean square consistency of give

see, for example, van der Vaart and Wellner [58]. By assumption, R2(Qn, Q0) = oP0 (n−1/2). Thus:

as desired.

Proof of Theorem 6. For all j = 1,…, J, we have that:

Summing over j and using (13) gives:

We also have that:

The above follows from the first by applying the law of total expectation conditional on the training sample, and then noting that each only relies on through the finite dimensional parameter εn. Because GLM-based parametric classes easily satisfy an entropy integral condition [58], the consistency assumption on shows that the above is second order. We refer the reader to Zheng and van der Laan [55] for a detailed proof of the above result for general cross-validation schemes, including J-fold cross-validation.

It follows that:

Appendix B: Estimators of the mean outcome under the optimal rule

TMLE of the mean outcome under a given rule

This TMLE for a fixed dynamic treatment rule has been presented in the literature, but for the sake of being self-contained it will be shortly described here. The TMLE yields a substitution estimator that empirically solves the estimating equations corresponding to the efficient influence curve, analogous to Theorem 2 for general d. By substitution estimator, we mean that the TMLE can be written as the mapping Ψ applied to a particular Q.

Assume without loss of generality that Y ∈ [0, 1]. In this section we use lower case letters to emphasize when quantities are the values taken on by random variables rather than the random variables themselves, for example, our sample is given by (o1; …, on), where . The indicator for not being right censored at time j for individual i is given by a2(j)i.

Regress (yi : a2(0)i = a2(1)i = 1) on to get an estimate

| (16) |

Note that we have only used individuals who are not right censored at time 1 to obtain this fit. The above regression can be fitted using a data adaptive technique such as super-learning [59]. To estimate , use

where we remind the reader that we are treating the rule d = dn as a known function and that v is a function of that sets the indicators for not being censored to 1. Consider the fluctuation submodel

where

Let ε2n be the estimate for ε2 obtained by running a univariate logistic regression of (yi : i = 1, …, n) on (H2(gn)(oi) : i = 1, … n) using

as offset. This defines a targeted estimate

| (17) |

of the regression function, where we remind the reader that the targeted estimate is chosen to ensure that the empirical mean of the component is 0 when we plug in the estimate of the intervention mechanism and the targeted estimate of the regression function for the unknown true quantities.

We now develop a targeted estimator of the second regression function in to ensure that the substitution estimator of will have empirical mean 0. Regress

on (l(0)i; a(0)i : a2(0)i = 1) to get the regression function

| (18) |

One can estimate this quantity using the super-learner algorithm among all individuals who are not right censored at time 0. For honest cross-validation in the super-learner algorithm, the nuisance parameter should be fit on the training samples in the super-learner algorithm. We refer the reader to Appendix B of van der Laan and Gruber [41] for a detailed explanation of this procedure. The same strategy holds for estimating the nuisance parameter g0 when necessary (e.g., in an observational study).

For an estimate of EP0[Yd|L(0)], one can use the regression function above, but with a(0) fixed to dA(0)(v(0)), which is itself a function of l(0). We will denote this function by l(0) ↦ En[Yd|L(0) = l(0)]. We now wish to fluctuate this initial estimator so that the plug-in estimator of has empirical mean 0. In particular, we use the submodel

where

Let ε1n be the estimate for ε1 obtained by running a univariate logistic regression of

on (H1(gn)(oi) : i = 1, …, n) using (logitEn[Yd|L(0) = l(0)i : i = 1, …, n) as offset. A targeted estimate of EP0[Yd|L(0) is given by

| (19) |

Plugging the targeted regressions and gn into the expression for shows that this estimate of has empirical mean 0.

Let QL(0);n be the empirical distribution of L(0), and let be the parameter mapping representing the collection containing QL(0),n and the targeted regression functions in (17) and (19). This concludes the presentation of the components of the TMLE of EP0Yd. The discussion of properties of this estimator is continued in the main text.

CV-TMLE of the mean outcome under data adaptive V-optimal rule

Let be an estimator of the V-optimal rule d0. Firstly, without loss of generality we can assume that Y ∈ [0, 1]. Denote the realizations of Bn with j = 1, …, J, and let denote the estimated rule on training sample j. Let

| (20) |

represent an initial estimate of based on the training sample j, obtained analogously to the estimator in (16). Similarly, let gnj represent the estimated intervention mechanism based on this training sample , j = 1, …, J. Consider the fluctuation submodel

where

Note that the fluctuation ε2 does not rely on j. Let

where represents the fluctuated function in (20) and

| (21) |

for all . For each i = 1, …, n, let j(i) ∈ {1; …, J} represent the value of Bn for which element i is in the validation set. The fluctuation ε2n can be obtained by fitting a univariate logistic regression of (yi: i = 1, …, n) on (H2(gnj(i))(oi): i = 1, …, n) using

as offset. Thus each observation i is paired with nuisance parameters that are fit on the training sample which does not contain observation i. This defines a targeted estimate

| (22) |

of . We note that this targeted estimate only depends on Pn through the training sample and the one-dimensional ε2n.

We now aim to get a targeted estimate of EP0[Ydnj|L(0)]. We can obtain an estimate

| (23) |

in the same manner as we estimated the quantity in (18), with the caveat that we replace by and only fit the regression on samples that are not right censored at time 0 and are in training set j. For an estimate Enj[Ydnj|L(0)] of EP0[Ydnj|L(0)], we can use the regression function above but with a(0) fixed to dnj,A(0)(v(0)).

Consider the fluctuation submodel

where

Again the fluctuation ε1 does not rely on j. Let

where is defined in (21). For each i = 1, …, n, again let j(i) ∈ {1, …, J} represent the value of Bn for which element i is in the validation set. The fluctuation ε1n can be obtained by fitting a univariate logistic regression of

on (H1(gnj(i))(oi): i = 1, …, n) using

as offset. This defines a targeted estimate

| (24) |

of EP0[Ydnj|L(0)]. We note that this targeted estimate only depends on Pn through the training sample and the one-dimensional ε1n.

Let QL(0),nj be the empirical distribution of L(0)i for the validation sample . For all j = 1, …, J, let be the parameter mapping representing the collection containing QL(0),nj and the targeted regressions in (22) and (24). This defines an estimator of ψdnj0 = Ψdnj(P0) for each j = 1, …, J. CV-TMLE is now defined as . This CV-TMLE solves the cross-validated efficient influence curve equation:

Further, each only relies on through the univariate parameters ε1n and ε2n. This will allow us to use the entropy integral arguments presented in Zheng and van der Laan [55] which show that no restrictive empirical process conditions are needed on the initial estimates in (20) and (23).