Abstract

Background

This study focuses on the large outdoor markets of the capital of Madagascar, Antananarivo. As the largest metropolitan area in Madagascar with a population of nearly two million, the region has great capacity for consumption of medicinal plant remedies despite numerous pharmacies. Medicinal plant use spans all socioeconomic levels, and the diverse metropolitan population allows us to study a wide variety of people who consume these plants for medical purposes. The purpose of this study is to identify and generate a list of medicinal plants sold in the traditional markets with a focus on those collected in the forests around Antananarivo, get an idea of the quantities of medicinal plants sold in the markets around Antananarivo, and assess the economy of the medicinal plant markets.

Methods

In order to determine which medicinal plants are most consumed in Antananarivo, ethnobotanical enquiries were conducted in the five main markets of the capital city. Ethnobotanical surveys were conducted with medicinal plant traders, suppliers, harvesters and cultivators, with voucher specimens created from the plants discussed. Trade circuit information was established and the income generated by the trade of some of the species was assessed.

Results

The inventory of the Antananarivo markets resulted in a list of 89 commercialized plant species. Ten of the 89 were mentioned by 60-100 % of vendors. Profitability for vendors is high and competitive with other salaried positions within Antananarivo. Transportation costs are also high and therefore lower profitability for other members in the supply chain.

Conclusions

The markets of Antananarivo have always played a vital cultural role in the lives of urban Malagasy, but our study shows they also play an economic role not only for urban residents but rural harvesters as well. Continued research and monitoring of the non-timber forest products trade in Antananarivo is needed to better understand the impact of trade on the wild plant populations.

Keywords: Madagascar, Urban market, Medicinal plants

Background

The use of plants for medical treatment and therapy is a practice as old as humanity, dating as far back as the oldest known written documents and found in nearly every known culture [1–3]. Traditional medicine is rich due to the diversity of human groups, languages, and customs, combined with the diversity of ecological regions, leading to innovative plant use and specialized knowledge [4]. The World Health Organization estimates that nearly 80 % of the population in developing countries depends mainly on traditional medicine for the treatment of ailments [5]. The dependence on remedies derived from medicinal plants is particularly important in developing countries where modern medicine is often absent or simply too expensive [6, 7]. Economic devaluation of the developing countries leads to higher prices of pharmaceuticals and makes medicinal plants and traditional medicine more attractive [8]. Additionally, some prefer traditional medicine for various reasons including familiarity, tradition and perceived safety [9, 10].

Medicinal plants can be of great importance in the daily lives of those who live near places where they grow, not only for their healing traditions but as a commodity to take to the urban areas where they are not locally found to be sold in the marketplace [11]. Trade of non-timber forest products (NTFP) has been a mainstay for rural economies with a large majority being sourced from wild populations [12]. Rural farmers and residents therefore have a financial interest to not only exploit and develop trade of these natural resources [13], but also to consider conservation measures [14, 15]. The domestic market of medicinal plants of Madagascar is not well documented, and the market for medicinal plants and derivatives only represents a small fraction compared to all internal and external trade of the country [16]. Our study focused on the city of Antananarivo and its medicinal plant markets. As the capital of Madagascar Antananarivo is the largest metropolitan area with a population of nearly 2 million, and the region has great potential for consumption of medicinal plant remedies despite numerous allopathic pharmacies [11]. Medicinal plant-use in Madagascar spans all socioeconomic levels and the diverse metropolitan population allowed to study a wide variety of people using plant products. The objective of this study was to identify and generate a list of medicinal plants sold in the traditional markets with a focus on those collected in the forests around Antananarivo, as well as getting information on the quantities of medicinal plants sold in the markets around Antananarivo, and to assess the economy of the medicinal plant markets. Interviews were started with the vendors at the major markets of Antananarivo, and continued with suppliers wherever possible. We then tried to elucidate who cultivated or harvested plants sourced by the suppliers and finally who held the knowledge of traditional plant medicine for the region.

Methods

Study area

Antananarivo is the capital of Madagascar, the fourth largest island in the world, and centrally located in the highlands at nearly 1,300 meters above sea level [17]. We conducted surveys in five major markets of Antananarivo: the Esplanade Analakely, Petite Vitesse, Pavilion Analakely, Isotry and Andravohangy. These markets were chosen based on the following criteria: market size and popularity, medicinal plant species sold on the premises, and knowledge of vendors regarding the use and sale of medicinal plants. Furthermore, markets in Antananarivo are housed in permanent buildings where vendors occupy permanent booths, which allowed for repeat visits to the same vendor to update lists and conduct further interviews.

Markets

The medicinal plant market includes two subsectors: the traditional medicinal plant market and the pharmaceutical market. The traditional plant market, known as raokandro, includes plants for public use with little to no processing (dried, raw material). The plants were sold either singularly or as a mix with other plants for a particular treatment. Other types of legal plant markets in Antananarivo are pharmaceutical, cosmetics and aromatherapy shops marked with HOMEOPHARMA and IRMA, selling mostly medicinal plants and medicinal plant products that have undergone extensive modification (liquid extract, cream, ointment). The present study focused on the medicinal plant trade within the raokandro. A variety of actors were involved in the sale of medicinal plants. These included operators, collectors, harvesters, and small retailers. The definitions we followed were taken from the ministerial decree number 2915/87 of 30 June 1987 and the Decree of 17 November 1930 mentioned in Articles 32 and 33 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of participants within the herbal market trade scheme. Types of collectors and their role within the trade as defined by the Madagascar government

| Operators | Persons who legally hold a license or an operating agreement to operate and collect medicinal plants and forest products to sell or use as raw materials. |

| Collectors | These are individuals who collect plants from those who harvest in the forest. They are authorized to carry out the grouping of plants with several collectors. |

| Harvesters | These are the persons authorized to conduct harvesting or gathering medicinal plants for commercial purposes |

| Rural harvesters | Those who come from the rural areas surrounding the city of Antananarivo to deliver medicinal species to the market sellers |

| Urban harvesters | people living in the vicinity of the capital, which also make deliveries to vendors of medicinal plants in the traditional market of Antananarivo |

| Public resellers (vendors) | These are the people who sell plants to the public. Called "tapa-mpivarotra kazo" or "mpivarotra raokandro” in Malagasy. |

Ethnobotanical surveys

To gather information about the market of medicinal plants, a series of semi-structured interviews were conducted with traders at the traditional markets (raokandro) of Antananarivo after obtaining oral prior informed consent. Questionnaires were used as a foundation for discussions with the collectors and traders. During market interviews we conducted our survey individually and iteratively [18]. All medicinal species that were discussed with the vendors were also purchased from the vendors at the regular price. Medicinal plants were then identified at the department of Plant Biology and Ecology at the University of Antananarivo and crosschecked with published ethnobotanical and floristic literature where available [19–22]. Plant names follow www. TROPICOS.org. Herbarium vouchers were deposited at the herbaria of Centre National de la Recherche Appliquée au Developement Rural (TEF), Parc de Tsimbazaza (TAN) and Missouri Botanical Garden (MO).

Statistical analysis

For each medicinal plant a Use Index (UI%) was calculated to give a ranking of the importance of the use and trade of medicinal species in markets of Antananarivo. The UI% is calculated from the formula, UI = (na/NA) x 100, where na is the number of interviewees who cite the species as useful and NA is the totally number of people interviewed [23]. In this case, na represents represent the number of vendors who sell a particular medicinal species. The following formulas were used to calculate the profit margin of the various intermediaries surveyed. For sellers, Bv = PV- PA where the benefit to vendors (Bv) is the difference between the sale price (PV) and the purchase price (PA). For harvesters (rural and urban), Bh = ΣR - ΣEx, where the benefit to harvesters (Bh) is the difference between the revenue (R) and expenditure costs (Ex). Profit margin (PM) was calculated with PM = B / ΣR, based on [23].

Results and discussion

We interviewed 86 people in the traditional markets of medicinal plants in Antananarivo. Table 2 summarizes the survey sites and the number of informants surveyed.

Table 2.

Market sites and number of informants surveyed

| Market | Number of vendors | Rural harvesters | Intermediaries or Urban harvesters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esplanade Analakely | 9 | 0 | 3 |

| Petite Vitesse | 21 | 15 | 7 |

| Andravoahangy | 21 | 5 | 0 |

| Pavilion Analakely | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Isotry | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 56 | 20 | 10 |

| Total interviewed | 86 | ||

We were able to identify 89 medicinal plant species from 56 vendors. A list of medicinal plants is presented in Table 3. The actual number of species sold is likely higher than what we were able to identify because of the study’s limited duration [24]. Furthermore, vendors spoke only about plants that at the time of the interview were available in their stalls. Other plants might be sold at other times, but if they were not available for purchase the sellers did not mention them.

Table 3.

List of medicinal plants sold at the Antananarivo medicinal markets. Scientific name, vernacular name, plant part used, disease treated and voucher number [MTR = Randriamiharisoa, Maria T.] for all 89 plants identified at the Antananarivo Markets. Use citations were compared with Madagascar ethnobotany published literature: [1] Boiteau P, Allorge- Boiteau L, 1993; [2] Samyn, JM, 1999; [3] Gurib-Fakim A, Brendler T, 2004

| Scientific name | Vernacular name | Part used | Application | Uses cited in literature | Voucher number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | |||||

| Avicennia marina (Forssk.) Vierh. | Afiafy | Leaf | Stomach ulcer | MTR142 | |

| Justicia sp. | Belohalika | Leaf | Neuralgia | MTR190 | |

| Amaranthaceae | |||||

| Cyathula uncinulata (Schrad.) Schinz | Tangogo | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis, diabetes, cardiac problems | MTR163 | |

| Anacardiaceae | |||||

| Anacardium occidentale L. | Mahabibo | Leaf | Diabetes, hemorrhoids, stomach ulcer, allergies, hepatitis, wounds, incontinence, anorexia | MTR127 | |

| Rhus taratana (Baker) H. Perrier | Andriambavimahery | Leaf | Wounds, stomach ulcer | MTR174 | |

| Apiaceae | |||||

| Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. | Talapetraka | Entire plant | Stomach ulcer, wounds | Wounds3, skin eczema3, accesses3, conjunctivitis3 | MTR138 |

| Apocynaceae | |||||

| Catharanthus lanceus (Bojer ex A. DC.) Pichon | Vonenina | Root | Cancer | Diuretic2, purgative2, vermifuge2, sores2 | MTR161 |

| Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don | Vonenina | Root | Cancer, appetite suppressant | Hypotensive1, antidepressant1, antitumoral1, purgative2, diabetes2, appetite suppressant2, vermifuge3, diarrhea3, dysentery3 | MTR162 |

| Cynanchum sp. | Vahamavo | Leaf | Asthenia, erectile dysfunction | MTR191 | |

| Pentopetia sp. | Tandrokosy | Leaf | Cough, hepatitis, neuralgia | MTR189 | |

| Araliaceae | |||||

| Schefflera bojeri (Seem.) R. Vig. | Tsingila | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis | MTR143 | |

| Schefflera sp. | Ramadio | Leaf | Neurasthenia, back pain | MTR144 | |

| Asteraceae | |||||

| Brachylaena ramiflora (DC.) Humbert | Ramanjavona | Leaf | Asthenia, stomach ulcer, | MTR173 | |

| Cynara scolymus L. | Artichaut | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis | MTR192 | |

| Distephanus polygalifolius (Less.) H. Rob. & B. Kahn | Ninginingina | Leaf | Syphilis, neuralgia, back pain, stomach ulcerm, hepatitis, albumin, incontinence | MTR136 | |

| Emilia citrina DC. | Tsiotsiona | Leaf | Asthenia, anorexia | MTR202 | |

| Helichrysum faradifani Scott- Elliot | Haihalala | Leaf | Gonorrhea, cough, asthenia, fever, stomach ulcer, hepatitis | MTR159 | |

| Helichrysum gymnocephalum (DC.) Humbert | Rambiazina | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, cough, wound, severe headache | Headaches1, bronchitis1, ulcers1, heartburn2, upset stomach2, fever2, diarrhea3, dysmenorrhea3, rheumatism3, gout3 | MTR160 |

| Inulanthera brownii (Hochr.) Källersjö | Kelimavitrika | Leaf | Immune system of children, erectile dysfunction, stiffness | MTR128 | |

| Psiadia altissima (DC.) Drake | Sakatavilotra | Leaf | Cough, wound, diarrhea | Fever3, abdominal pain3, antiseptic3, toothache3, boils3 | MTR220 |

| Senecio canaliculatus Bojer ex DC. | Ramijaingy | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, gastroenteritis, syphilis | MTR201 | |

| Vernonia appendiculata Less. | Ambiaty | Leaf | Fever, nerves | MTR193 | |

| Bignoniaceae | |||||

| Jacaranda mimosifolia D. Don | Zaharandaha | Leaf | Sinusitis, severe headache | MTR145 | |

| Phyllarthron bojeranum DC. | Zahana | Leaf | Asthenia, erectile dysfunction, severe headache, gonorrhea, cough, syphilis | MTR175 | |

| Symphytum orientale L. | Konsody ou Maseza | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis | MTR203 | |

| Cactaceae | |||||

| Cereus triangularis (L.) Haw. | Tsilo | Root | Kidney stones, urinary tract problems, syphilis, gonorrhea | MTR158 | |

| Canellaceae | |||||

| Cinnamosma madagascariensis Danguy | Mandravasarotra | Bark | Astenia, erectile dysfunction, stomach ulcer | Stomach pain3, colic3, analgesic3, indigestion3, stimulant3, cough3, dysentery3 | MTR194 |

| Celastraceae | |||||

| Mystroxylon aethiopicum (Thunb.) Loes. | Fanazava | Leaf | Neuralgia, hepatitis, albumin, erectile dysfunction, back pain, urinary tract problems, stomach ulcer, hypertension, immune deficiency | Fatigue3,neuralgia3, purgative3, vertigo3 | MTR126 |

| Combretaceae | |||||

| Combretum coccineum (Sonn.) Lam. | Tamenaka | Fruit | Intestinal parasites | Anthelmintic,3, liver problems3 | MTR200 |

| Terminalia catappa L. | Atafana | Leaf | Urinary tract problems | Astringent3, sudorific3, dysentery3 | MTR188 |

| Commelinaceae | |||||

| Commelina madagascarica C.B. Clarke | Nifinakanga | Leaf | Abortifacient, acne | MTR176 | |

| Crassulaceae | |||||

| Kalanchoe prolifera R. Hamet | Sodifafana | Leaf | Neurasthenia | Boils3, furuncles3, wounds3, rheumatism3 | MTR186 |

| Cyperaceae | |||||

| Cyperus papyrus subsp. madagascariensis (Willd.) Kük. | Fonjozoro | Stem | Emphysema, back pain | MTR146 | |

| Droseraceae | |||||

| Drosera madagascariensis DC. | Mahantanando | Leaf | Conjunctivitis, enurensis | Coughs3, toothpaste3, dyspepsia3, anemia3 | MTR129 |

| Ebenaceae | |||||

| Diospyros sp. | Bois de rose | Bark | Cysticercosis, intestinal parasites, taxoplasmosis, emphysema, diabetes, albumin regulation, allergies | MTR171 | |

| Equisetaceae | |||||

| Equisetum sp. | Tsitoatoana | Leaf | Constipation, urinary tract problems | MTR177 | |

| Euphorbiaceae | |||||

| Ricinus communis L. | Tanantanamanga | Leaf | Asthenia, hemorrhoids, wounds, intestinal parasites, cold | Galactagogue1,2, purgative1,2, laxative1,2, intestinal worms1, tapeworm1, headache2, rheumatism2, dental cavities2, wounds2, fevers2 | MTR164 |

| Fabaceae | |||||

| Caesalpinia bonduc (L.) Roxb. | Vatolalaka | Fruit | Hemorrhoids, appendicitis | MTR204 | |

| Phylloxylon xylophylloides (Baker) Du Puy, Labat & Schrire | Arahara | Leaf | Hepatitis, urinary tract problems, pharyngitis | MTR184 | |

| Senna septentrionalis (Viv.) H.S. Irwin & Barneby | Anjanajana | Leaf | Immune system children, gastroenteritis | MTR147 | |

| Senna occidentalis (L.) Link | Tsotsorinangatra | Stem | Syphilis, gonorrhea, prostate tumor, hypertension, hepatitis, rheumatism | MTR165 | |

| Tamarindus indica L. | Voamadilo | Leaf | Constipation, gastroenteritis, wounds | Laxative1,vermifuge1, stomach ache1, general wounds1 | MTR125 |

| Gentianaceae | |||||

| Tachiadenus longifolius Scott- Elliot | Tapabatana | Leaf | Diarrhea, stomach ulcer | MTR172 | |

| Gesneriaceae | |||||

| Streptocarpus hilsenbergii R. Br. | Mangavony | Enitre plant | Hepatitis, acne | MTR185 | |

| Hydrostachyaceae | |||||

| Hydrostachys stolonifera Baker | Tsilavondrina | Leaf | Asthenia | MTR187 | |

| Hypericaceae | |||||

| Harungana madagascariensis Lam. ex Poir. | Harongana | Leaf | Wounds, asthma, cough, stomach ulcer, hepatitis, gastroenteritis, albumin, allergies, insomnia | Scabies1,2, stomach ache1, flatulence1, anticatarrhal1,2, bladder infections2, syphilis2, menstruation regulation2, fever2, wounds2, diarrhea2,3, hemorrhoids2, skin diseases3 | MTR130 |

| Psorospermum sp. | Todihazo | Stem | Scabies, leprosy | MTR148 | |

| Psorospermum ferrovestitum Baker | Andriambolamena | Leaf | Female infertility, abortifacient, stomach ulcer, hypertension, intestinal parasites | MTR166 | |

| Lamiaceae | |||||

| Ocimum gratissimum L. | Romba | Leaf | Severe headache, albumin, wounds, abortifacient, cold, low calcium, dental problems | Digestion3, chest complaints3, diarrhea3, vomiting3, anticatarrh3, antiseptic3 | MTR205 |

| Tetradenia riparia (Hochst.) Codd | Borona | Leaf | Cough, wounds, hepatitis | MTR221 | |

| Lauraceae | |||||

| Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl | Ravitsara | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis, abortifacient, jaundice, hypertension, appendicitis, rheumatism | Fevers3, rheumatism3, abortifacient3 | MTR122 |

| Loganiaceae | |||||

| Anthocleista madagascariensis Baker | Landemy | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, diarrhea, malaria, constipation, abdominal colic, severe headache | Fever1,2, dysentery1,2, emetic1,2, laxative1,2 | MTR149 |

| Lycopodiaceae | |||||

| Lycopodium sp. | Karakaratoloha | Leaf | Hepatitis, hypertension, gastroenteritis, epilepsy | MTR157 | |

| Meliaceae | |||||

| Azadirachta indica A. Juss. | Nimo | Leaf | Asthenia, diabetes, albumin, rheumatism, pelvic pain, boils, hepatitis, kidney stones, burns, constipation, high cholesterol | MTR124 | |

| Cedrelopsis grevei Baill. | Katrafay | Bark | Asthenia, erectile dysfunction, neurasthenia, back pain | MTR141 | |

| Neobeguea mahafaliensis J.-F. Leroy | Andy | Bark | Asthenia, erectile dysfunction' | MTR183 | |

| Molluginaceae | |||||

| Mollugo nudicaulis Lam. | Aferotany | Entire plant | Cough, gastroenteritis | MTR178 | |

| Moraceae | |||||

| Ficus reflexa Thunb. | Nonoka | Leaf | Hepatitis, gastroenteritis, wounds, albumin, hemorrhoids | MTR167 | |

| Morus alba L. | Voaroihazo | Leaf | Low calium, anorexia | MTR209 | |

| Primulaceae | |||||

| Embelia concinna Baker | Tanterakala | Leaf | Intestinal parasites, erectile dysfunction | MTR206 | |

| Myrtaceae | |||||

| Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. | Kininina oliva | Leaf | Cold, severe headache | MTR210 | |

| Eucalyptus sp. | Kininimpotsy | Leaf | Cold, severe headache | MTR211 | |

| Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels | Rotra | Bark | Diarrhea, gastroenteritis | MTR131 | |

| Nymphaeaceae | |||||

| Nymphaea sp. | Betsimilana | Leaf | Female infertility, abortifacient, albumin, painful menstruation | MTR219 | |

| Onagraceae | |||||

| Ludwigia octovalvis (Jacq.) P.H. Raven | Volondrano | Leaf | Emphysema | Nose bleeds3, diarrhea3, malnourishment3 | MTR150 |

| Orchiaceae | |||||

| Vanilla madagascariensis Rolfe | Vahinamalona | Stem | Erectile dysfunction, asthenia | Aphrodisiac1, | MTR208 |

| Pedaliaceae | |||||

| Uncarina sp. | Farehitra | Leaf | Acne | Dandruff3, alopecia3 | MTR132 |

| Poaceae | |||||

| Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | Fandrotrarana | Entire plant | Syphilis, kidney stones | MTR168 | |

| Imperata cylindrica (L.) Raeusch. | Fakatenina | Root | Kidney stones | MTR182 | |

| Zea mays L. | Volokatsaka | Silk | Urinary tract problems, hepatitis, kidney stones | MTR156 | |

| Pteridaceae | |||||

| Adiantum capillus-veneris L. | Ampanga | Leaf | Allergies, cough | Respiratory problems1, diuretic1, chickenpox1, measles1 | MTR207 |

| Ranunculaceae | |||||

| Clematis mauritiana Lam. | Farimafy | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis, erectile dysfunction | Antiasthmatic3, rheumatism3, cough3, bronchitis3, abdominal pains3 | MTR179 |

| Rubiaceae | |||||

| Oldenlandia sp. | Ahipody | Leaf | Scabies, leprosy | MTR218 | |

| Paederia foetida L. | Vahamaibo, laingomaimbo | Leaf | Dental issues, wound, stomach ulcer, gastroenteritis | Diuretic1,3, diaphoretic1, purgative1, skin issues1,3, ulcers1, boils3, venereal diseases3, bladder issues3, gastric pains3 | MTR123 |

| Pauridiantha paucinervis (Hiern) Bremek. | Tamirova | Leaf | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis, hypertension, urinary tract problems, rheumatism, malaria, albumin, diabetes | MTR153 | |

| Rutaceae | |||||

| Toddalia asiatica (L.) Lam. | Fanala simba | Elaf | Syphilis, gonorrhea | Malaria3, digestive complaints3, fever3, cholera3, diarrhea3, rheumatism3, syphilis3 | MTR181 |

| Salicaceae | |||||

| Homalium parkeri Baker | Hazomby | Bark | Dental issues | MTR140 | |

| Salviniaceae | |||||

| Azolla sp. | Ramilamina | Lower | Cardiac arrest | MTR170 | |

| Smilacaceae | |||||

| Smilax anceps Willd. | Avotra | Leaf | Gastroenteritis, abdominal colic | Varicose veins3,eczema3, liver disorders3 | MTR180 |

| Solanaceae | |||||

| Brugmansia candida Pers. | Datroa | Leaf | Epilepsy, paraplegia | MTR152 | |

| Physalis peruviana L. | Voanantsindrana | Leaf | Rheumatism, urinary tract problems, syphilis, stomach ulcer, hepatitis | Eat berries before physical exertion1, diuretic1,3, kidney stones1, rheumatism1, abscess2, liver disease2, gout3, fever3, heart palpitations3, emollient3 | MTR137 |

| Solanum mauritianum Scop. | Seva | Leaf | Hepatitis, wound | General disinfectant1, Stomach ulcers2 | MTR151 |

| Stilbaceae | |||||

| Nuxia capitata Baker | Valanirana | Leaf | Gastroenteritis, asthenia, cough | MTR169 | |

| Urticaceae | |||||

| Urera acuminata (Poir.) Gaudich. ex Decne. | Sampy vato | Leaf | Kidney stones, abortifacient, hepatitis, stomach ulcer | Irritant to skin and eyes3, childbirth3 | MTR133 |

| Verbenaceae | |||||

| Lantana camara L. | Randriaka | Leaf | Hemorrhage, hypertension | MTR155 | |

| Xanthorrhoeaceae | |||||

| Aloe macroclada Baker | Vahona | Leaf | Cancer, allergies, acne, fungus | MTR139 | |

| Dianella ensifolia (L.) DC. | Erana | Leaf | Intestinal parasites, constipation, back pain, gonorrhea | Eczema3, dysentery3, stomach pains3 | MTR154 |

| Zingiberaceae | |||||

| Zingiber sp. | Tamotamo | Tuber | Cough | MTR135 | |

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Sakamalao | Tuber | Cough | MTR134 |

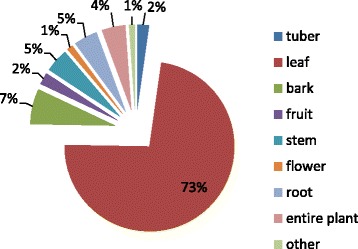

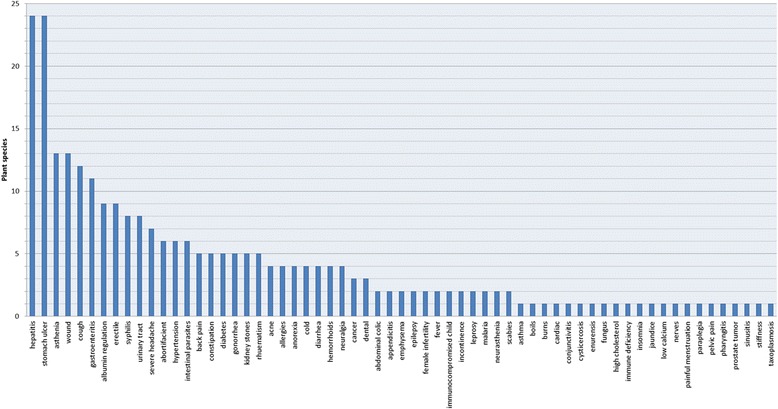

Among the medicinal species available at the major markets of the city of Antananarivo, we encountered nine plant part used: leaves (73 %), bark (7 %), stems (5 %), roots (5 %), entire plant (4 %), fruit (2 %), tuber (2 %), flower (1 %), other (1 %). (Fig. 1) Leaves were by far the most common plant material used, followed by bark. While leaves and bark were often well represented in other studies, only 50 % of the combined total in our study were leaves and bark, similar to in Sierra Leone [25]. These most common health complaints treated with plants were hepatitis, kidney stones, asthenia, wounds, coughs and gastroenteritis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Plant parts most commonly sold

Fig. 2.

Number of plant species sold for specific ailments

Most traded medicinal species

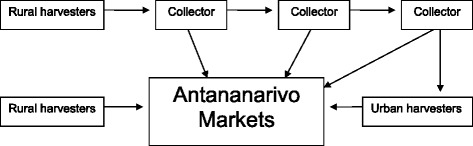

Table 4 lists the ten most traded species in the markets, including the Use Index calculated for each of these species, which varied from 61 % to 100 %. Prices are typically the main economic indicators about the supply and demand for a product, with higher prices indicating species with higher demand and lower supply. However, we found that the organization of economic actors within the regional medicinal plant trade was also a determinant of prices, often affecting the price based on who and how the species was sourced. Vendors bought their plants from rural harvesters, urban harvesters, and collectors, which is a common trade pattern found in other parts of Africa as well [26]. Increased number of intermediaries before a species reaches the sellers increased the price on the market. Two commercial channels could be distinguished: a short circuit, when harvesters moved to Antananarivo to be closer to the markets in order to sell their products directly themselves, and a long circuit, consisting of a long chain of intermediaries the products passed through before reaching sellers in Antananarivo (Fig. 3). The purchase price of medicinal plants varied widely depending on the species, but we found that prices were constant for a given species.

Table 4.

Use index calculated for the most traded species and their treatment associations

| Family | Scientific name | Vernacular name | Application | Use index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubiaceae | Pauridiantha paucinervis (Hiern) Bremek. | Tamirova | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis, high blood pressure, urogenital diseases, rheumatism, malaria, edema, diabetes | 100 % |

| Meliaceae | Cedrelopsis grevei Baill. | Katrafay | Asthenia, erectile dysfunction, back pain | 100 % |

| Meliaceae | Neobeguea mahafaliensis J.-F. Leroy | Andy | Asthenia, erectile dysfunction | 82 % |

| Cactaceae | Cereus triangularis (L.) Haw. | Tsilo | Kidney stones, dysuria, anuria, syphilis, gonorrhea | 78 % |

| Fabaceae | Senna occidentalis (L.) Link | Tsotsorinangatra | Syphilis, gonorrhea, enlarged prostate, high blood pressure, rheumatism, hepatitis | 70 % |

| Lamiaceae | Ocimum gratissimum L. | Romba | Intense headache, edema, wounds, repeated miscarriages, cold, hypocalcemia, dental pain | 65 % |

| Boraginaceae | Symphytum orientale L. | Konsody | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis | 65 % |

| Asteraceae | Cynara cardunculus subsp. flavescens Wiklund | Artichaut | Stomach ulcer, hepatitis | 64 % |

| Asteraceae | Distephanus polygalifolius (Less.) H. Rob. & B. Kahn | Ninginingina | Syphilis, neuralgia, back pain, stomach ulcer, hepatitis, edema, enuresis | 61 % |

| Urticaceae | Urera acuminata (Poir.) Gaudich. ex Decne. | Sampivato | Kidney stones, repeated miscarriages, hepatitis, stomach ulcer | 61 % |

Fig. 3.

Market chain of medicinal plants in sold in Antananarivo

However, product price increased with each change of hands as transportation costs or other fees incurred. As found in other parts of the world, the amount of time, energy and resources needed to transport medicinal plants to the market was considered extremely high [27]. In addition, the price also fluctuated depending on the customer's apparent wealth and the type of market (i.e.: tourist handicraft market). Medicinal plants were often supplied from a collector two to four times a week, while some species were only delivered once a month or once a year (in the case of plants came from other provinces of Madagascar). Urban harvesters could afford to bring small amounts of plants (a basket or box) as they sold their products almost daily. Table 5 summarizes the types of providers and delivery frequency by type of market.

Table 5.

Suppliers and frequency of deliveries at each market site

| Market | Frequency of delivery | Transportation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural harvesters | Urban harvesters | Collection | ||

| Andravoahangy | 2 times a week | Daily | 3x/month | By foot |

| Isotry | Irregular | Daily | Irregular | By foot |

| Petite vitesse | 4 times a week | Daily | 1- 2 / week | By foot |

| Esplanade Analakely | Irregular | Daily | Irregular | By foot |

Local markets worldwide are a thriving business for both rural and urban dwellers, with a steady demand for medicinal plants. To understand the possible benefits for rural harvesters, several factors needed to be taken into account: 1) the cost of transporting goods 2) the frequency of deliveries to the Antananarivo markets 3) the quantity and value of the species transported to the market. Transport costs from rural areas of Antananarivo depended greatly upon the state of the road and mode of transportation and varied from $ 0.45 - $ 1.34 per person transporting plants. The most common mode of transport was carrying plant products “on their backs”, or by hand, from the rural areas to the city market, with costs ranging from $ 0.08 – $ 0.15 per bag. Overall, transportation costs to deliver the goods to the vendors of medicinal plants in the major markets of the city of Antananarivo ranged anywhere from $ 3.39 - $ 8.57 per week. If four bags of medicinal plants (which was the standard weekly amount per vender) were sold at a price of $ 4 - $ 5 per bag, earnings were $ 12 - $ 20 a week. The profit margin ranged from 40 % - 81 %.

Case study: Pauridiantha paucinervis and Mystroxylon aethiopicium

To further analyze the trade value of the medicinal plants in Antananarivo, we used the most used single species, Pauridiantha paucinevris, and a species that was present in most of the mixtures, Mystroxylon aethiopicium for closer analysis.

In the market, Pauridiantha paucinervis was sold packaged in a sealed, labeled bags. We found that package was uniform in all markets. Collectors sold this product to vendors for an average of $ 0.06 per package, and the frequency of deliveries was based on fluctuating demand in the markets. The selling price of the product in the market ranged from $ 0.08 - $ 0.17. Thus, the selling price of this product was double or even triple compared to its purchase price. According to our surveys vendors sold an average of six bags of P. paucinervis each day. Thus, the average earnings for the sale of P. paucinervis amounted to $ 0.50 per day, and the monthly earnings could be upwards of $ 22.50.

Mystroxylon aethiopicium was sold at $ 0.10 - $ 0.20 per package, but this species was only rarely sold alone, but rather was packaged with other herbs to form a tea to treat specific ailments. Sellers bought from collectors once a week, and the order quantity, depending heavily on supply and demand, was often irregular. The purchase price of this species from suppliers was $ 0.03 – $ 0.30, depending on volume. The profit margin of sales was 100 % to 150 % if the plant was sold alone, and even higher if it was combined with other herbs. In the latter case, the sale price varied according to the type of disease and also the amount needed for treatment. Vendors sold an average of 10 packets of M. aethiopicium a day, yielding an average of $ 0.30. The average monthly income for a vendor selling M. aethiopicium was about $10. Therefore, the combined sale of only P. paucinervis and M. aethiopicium averaged a monthly gross income of $25. Considering that the professional monthly minimum wage guarantee in Madagascar is $25, the medicinal plant trade can be considered lucrative. However, given the limited amount of time, and limited number of interviews, we could not elucidate the exact quantity of plant material sold in the markets.

Conclusions

Market studies of non-timber forest products (NFTP) have in the past focused mostly on rural economies and export markets. Recently, increased interest in the domestic marketplace has resulted in more data about economic value of NFTP in the domestic medicinal plant trade. It is difficult to quantify the number of medicinal plants that circulate in the markets of a city like Antananarivo, because this number is highly dependent on market dynamics, which can be quite irregular even for a single plant species. But our estimates show that the sale of medicinal plants in the domestic market provided income for all players - vendors, collectors and harvesters - allowing them to supplement or fully supply their annual income. The impact of these urban traditional markets on the urban and rural economy can be substantial [28]. This booming business has real implications for conservation concerns, which should be researched further to fully explore the impact of the medicinal plant trade on the ecological well-being of the forests where the plants are sourced. Further research and monitoring of the Antananarivo markets will also be invaluable to chart the sustainable use of wild natural resources.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Missouri Botanical Garden and the Plant Biology and Ecology Department at the University of Antananarivo for their support and cooperation while carrying out this research. We thank our supervisors for their valuable advice, encouragement and methodological guidelines. We also thank the vendors in all of the markets of Antananarivo for freely giving their time and knowledge.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors designed the study and contributed to writing the manuscript. MNR conducted the interviews and completed the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Maria Nirina Randriamiharisoa, Email: randriamiharisoa.maria@yahoo.fr.

Alyse R. Kuhlman, Email: Alyse.Kuhlman@mobot.org

Vololoniaina Jeannoda, Email: vololoniaina.jeannoda@gmail.com.

Harison Rabarison, Email: rabarisonhr@yahoo.fr.

Nivo Rakotoarivelo, Email: nivo.rakotoarivelo@mobot-mg.org.

Tabita Randrianarivony, Email: tabita.randrianarivony@mobot-mg.org.

Fortunat Raktoarivony, Email: fortunat.rakotoarivony@mobot-mg.org.

Armand Randrianasolo, Email: armand.randrianasolo@mobot.org.

Rainer W. Bussmann, Email: rainer.bussmann@mobot.org

References

- 1.Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Natural products: a continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(6):3670–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowler MW. Plants, medicines and man. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006;86:1797–1804. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randimbivololona F. Research, valorization and exploitation of biological resources for medicinal purposes in the Malagasy Republic (Madagascar) J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;51:195–200. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01361-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultes RE. The Importance of Ethnobotany in Environmental Conservation. Am J Econ Sociol. 1994;53:202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1536-7150.1994.tb02586.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham AB. African Medicinal Plants: Setting Priorities at the Interface between Conservation and Primary Health Care. People and Plants Working Paper 1. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1993.

- 6.Randrianarivelojosia M, Rasidimanana VT, Rabarison H, Cheplogoi PK, Ratsimbason M, Mulholland DA, Mauclère P. Plants traditionally prescribed to treat tazo (malaria) in the eastern region of Madagascar. Malar J. 2003;2:25. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-2-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novy JW. Medicinal plants of the eastern region of Madagascar. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;55:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(96)01489-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ndoye O, Ruiz Perez M, Eyebe A. The markets of non-timber forest products in the humid forest zone of Cameroon. Rural Development Forestry Network 1998, Network Paper 22c. Center for International Forestry Research, Yaoundé, Cameroon.

- 9.Sheldon JW, Balick MJ, Laird SA. Medicinal plants: can utilization and conservation coexist? Adv Econ Bot. 1997;12:1–104. [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Andel T, Carvalheiro LG. Why Urban Citizens in Developing Countries Use Traditional Medicines: The Case of Suriname. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:687197. doi: 10.1155/2013/687197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ticktin T. The ecological implications of harvesting non-timber forest products. J Appl Ecol. 2004;41:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2004.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton A. Medicinal Plants and Conservation: Issues and Approaches. London: WWF UK report; 2003.

- 13.Augustino S, Gillah PR. Medicinal Plants in Urban Districts of Tanzania: Plants, Gender Roles and Sustainable Use. Int Forest Rev. 2005;7:44–51. doi: 10.1505/ifor.7.1.44.64157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ros-Tonen M. The role of non-timber forest products in sustainable tropical forest management. Holz als Roh-und Werkstoff. 2000;58(3):196–201. doi: 10.1007/s001070050413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnold MJE, Ruiz Perez M. Can non-timber forest products match tropical forest conservation and development objectives? Ecol Econ. 2001;39:437–447. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(01)00236-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Geneva: World Wide Fund for Nature; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Madagascar: Profil Urbain D’Antananarivo. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlement Program; 2012.

- 18.Ramamonjisoa BS. Méthodes d’enquêtes : manuels à l'usage des praticiens. Antananarivo: Manuel forestier n° 11 du Département Eaux et Forêts, École Supérieure des Sciences Agronomiques; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boiteau P, Allorge-Boiteau L. Plantes médicinales de Madagascar: Cinquante- huit plantes médicinales utilisées sur le marché de Tananarive (Zoma) à Madagascar. Paris: Karthala; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samyn JM. Plantes utiles des hautes terres de Madagascar. Antananarivo: Graphoprint; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schatz G. Generic Tree Flora of Madagascar. Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurib-Fakim A, Brendler T. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of Indian Ocean Islands: Madagascar, Comoros, Seychelles, and Mascarenes. Stuttgart, Germany: medpharm GmbH Scientific Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lance K, Kremen C, Raymond I. Extraction of forest Products: quantitative of a park and buffer zone and long-term monitoring. Antananarivo: Report to Park Delimitation Unit, WCS/PCDIM; 1994. pp. 549–563. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams V, Witkowski TF, Balkwill K. The use of incidence-based species richness estimators, species accumulation curves and similarity measures to appraise ethnobotanical inventories from South Africa. Biodivers Conserv. 2007;16:2495–2513. doi: 10.1007/s10531-006-9026-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jusu A, Cuni Sanchez A. Economic importance of the medicinal plant trade in Sierra Leone. Economic Botany. 2013;67:299–312. doi: 10.1007/s12231-013-9245-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jusu A, Cuni Sanchez A. Medicinal Plant Trade in Sierra Leone: Threats and Opportunities for Conservation. Economic Botany. 2014;68:16–29. doi: 10.1007/s12231-013-9255-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bussmann RW, Sharon D. Markets, Healers, Vendors, Collectors: The Sustainability of Medicinal Plant Use in Northern Peru. Mt Res Dev. 2009;29:128–134. doi: 10.1659/mrd.1083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shackleton S, Shanley P, Ndoye O. Invisible But Viable: Recognising Local Markets for Non-Timber Forest Products. Int Forest Rev. 2007;9(3):697–712. doi: 10.1505/ifor.9.3.697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]