Abstract

The hypothesis was tested that Cd2+ undergoes measureable reaction with the Zn-proteome through metal ion exchange chemistry. The Zn-proteome of pig kidney LLCPK1 cells is relatively inert to reaction with competing ligands, including Zinquin acid, EDTA, and apo-metallothionein. Upon reaction of Cd2+ with the Zn-proteome, Cd2+ associates with the proteome and near stoichiometric amounts of Zn2+ become reactive with these chelating agents. The results strongly support the hypothesis that Cd2+ displaces Zn2+ from native proteomic binding sites resulting in the formation of a Cd-proteome. Mobilized Zn2+ becomes adventitiously bound to proteome and available for reaction with added metal binding ligands. Cd-proteome and Zn-metallothionein readily exchange metal ions, raising the possibility that this reaction restores functionality to Cd-proteins. In a parallel experiment, cells were exposed to Cd2+ and pyrithione briefly to generate substantial proteome-bound Cd2+. Upon transition to a Cd2+ free medium, the cells generated new metallothionein protein over time that bound most of the proteomic Cd2+ as well as additional Zn2+.

Keywords: zinc proteome, cadmium, metallothionein, metal exchange

1. Introduction

Understanding how toxic metal ion (Mn+) cause cell injury requires that the intracellular sites of binding that cause the underlying changes in cell biochemistry be determined [1]. Considering the plethora of metal binding groups that adorn proteins (carboxylate, amine, thiolate, imidazole), nucleic acids (phosphate esters, purine and pyrimidine bases), and small molecules (e.g. glutathione thiol, carboxyl, and amine groups), multiple metal binding interactions can be proposed, in which L represents these ligands:

| (1) |

Despite decades of research into the biological toxicology of many metallic species, few sites have been identified that are causally linked to toxicity (e.g. M-Ln). In the case of Cd2+, the principal binding site that has dominated studies of this metal ion is metallothionein (MT) [2]. Among various functions, MT serves as a means of protection against this and other metal ions.

Cd2+ exposure causes the loss of function of a suite of Na+-dependent nutrient transporters in the kidney [3,4]. Recently, the Zn-finger transcription factor, Zn3-Sp1 has been shown to be the target of reaction with Cd2+ that leads to the down regulation of Na+-dependent glucose transporter mRNA and protein expression in the kidney proximal tubule [5,6]. In turn, cells lose their ability to transport glucose, a hallmark of human and rodent Cd2+ toxicity [7,8]. Direct metal ion exchange has been observed in vitro that may result in a rearrangement of finger structure and fully destroys function [9]:

| (2) |

Cd2+ causes a variety of other pathological effects in cultured cells [10,11]. Surely, all of these changes cannot be ascribed to reaction of Cd2+ with Zn3-Sp1 alone. Zn3-Sp1 is a member of the most common type of Zn-finger structure that contains Zn2+ binding sites involving two cysteine sulfhydryl and two histidine imidazole ligands [12,13]. There are hundreds of such proteins in mammalian cells and it may be expected that many react with Cd2+ as does Zn3-Sp1 [14]. Thus, to fully understand the determinants of toxicity, a proteomic approach is necessary, in which a number of sites may contribute to cell injury [15]. This paper begins a series of communications about new approaches to doing toxic metal proteomics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Zinquin acid (ZQ) was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA). The fluorophore was solubilized in DMSO and kept in the dark at 4 °C. Sephadex G-75 gel filtration chromatography beads were purchased from GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Chemical Companies and were reagent grade or highest purity available.

2.2. Cell culture

LLC-PK1 pig renal epithelial cells were purchased from the American Tissue Culture Company (ATCC CL101). Cells were grown in M199-Hepes culture media supplemented with 4% fetal calf serum (FCS), 50,000 units/l Penicillin, and 50mg/l Streptomycin and with 5% CO2 and 100% humidity at 37 °C.

2.3. Preparation of cell supernatant and proteome

Cells grown on 100mm diameter culture plates were rinsed three times with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution. Cells were scraped gently with a rubber cell scrapper and transferred to the cold (4 °C) Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) solution in a 50 ml centrifuge tube. Cells were then centrifuged at 640 × g for 4 minutes. The resulting cell pellet was transferred to a 12 × 80 mm thin walled tube with 4 mL of cold DPBS and recentrifuged at 1200 × g for 3 min. The supernatant was removed and 1 ml of cold Milli-Q (18MΩ resistant) purified water added. The suspension was sonicated at a power setting of 5 and a 40% pulse using the macro tip for 60 pulses. Cell supernatant was prepared by centrifugation of the sonicated mixture at 47000 × g for 20 min. at 4 °C. Supernatant was loaded onto a 0.7 cm × 80 cm Sephadex G-75 column equilibrated with degassed 20 mM Tris, 0.1 M KCl buffer, pH 7.4. Eluted fractions (1 ml) in the high molecular weight part of the separation profile were pooled, concentrated and designated as the proteome.

2.4. Treatment of supernatant and proteome with Zn2+ and Cd2+, gel filtration chromatography, and metal analysis

CdCl2 or ZnCl2 were reacted with cell supernatant and proteome for 60 min at room temperature. The mixture was loaded onto a Sephadex G-75 column as above. Fractions (1 ml) corresponding to high molecular weight proteins were collected and concentrated using an Amicon filtration device with 30 kDa cut off membrane. Concentrated Zn- or Cd-loaded proteome was either reacted immediately with competing ligands or stored in -80 °C for later use. Metal content of fractions was quantified using atomic absorption spectrophotometry (GBC 904) or inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Micromass Platform). Chromatographic results presented in the Figures are representative of at least 3 experiments.

2.5. Preparation and characterization of Zn7-MT and apo-MT

These proteins were prepared as described elsewhere [16]. For this study, rabbit liver MT-2 was used. It was fully characterized by metal, sulfhydryl, and protein analysis as Zn7-MT. The concentration of apo-MT was calculated as 7/20 of it thiol concentration. The rabbit MT-2 proteins have amino acid sequences that are nearly identical to that of porcine metallothionein, including invariant cysteine positioning and, in contrast to the pig proteins, have been extensively studied [2,17,18].

2.6. Cadmium pyrithione treatment of cell culture

Cells were exposed to 3 μM pyrithione and 60 μM CdCl2 for 30 min. Media was then removed and cells were washed 3 times with cold DPBS and either harvested for analysis or incubated for 6 h and 24 h in fresh media and FCS for further study. Cell supernatant was prepared using the above-mentioned procedure. Sephadex G-75 chromatography was employed as above to isolate the proteome from cell supernatant.

2.7. Fluorescence spectrophotometry

Fluorescence measurements were carried out on a Hitachi F-4500 fluorimeter. The excitation wavelength for Zinquin acid (ZQ) was 370 nm and emission spectra were obtained over the spectral range of 400 to 600 nm. All fluorescence spectra were recorded in arbitrary units at room temperature and corrected for the background fluorescence

3. Results

The hypothesis tested was that native Zn2+ binding sites within the proteome serve as major targets of reaction of Cd2+. Upon reaction, Cd2+ would displace Zn2+ and occupy a set of such binding sites. Collectively, these reactions can be described as

| (3) |

or they can be simplified by aggregating the sum of the reactive Zn-protein sites within the proteome as Zn-proteome:

| (4) |

The alternative hypothesis is that Cd2+ associates with other binding sites within the proteome as in reaction 1:

| (5) |

Reaction of Cd2+ with proteome

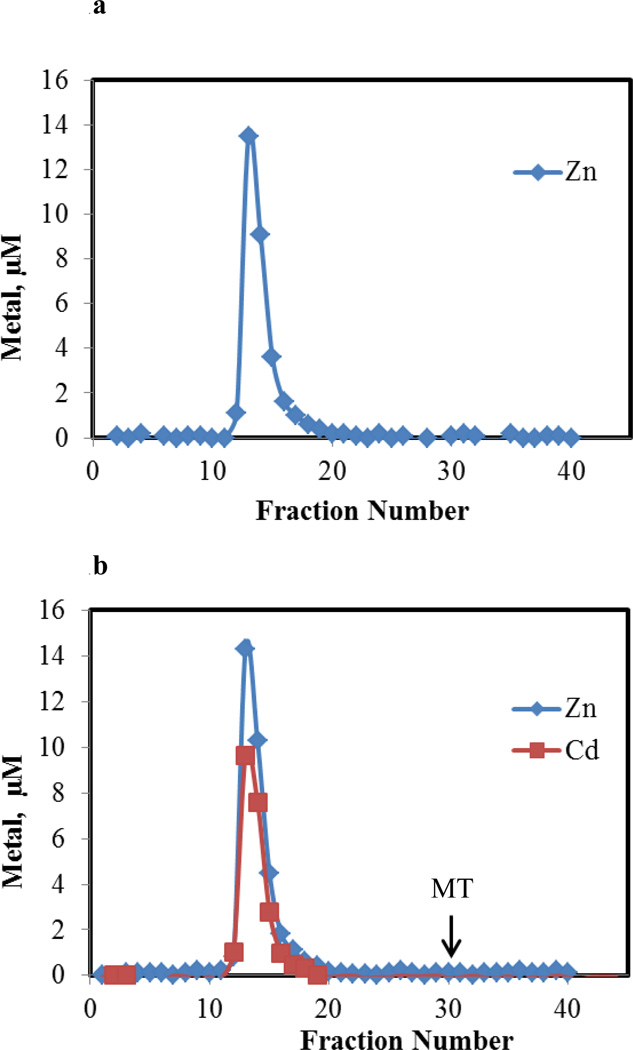

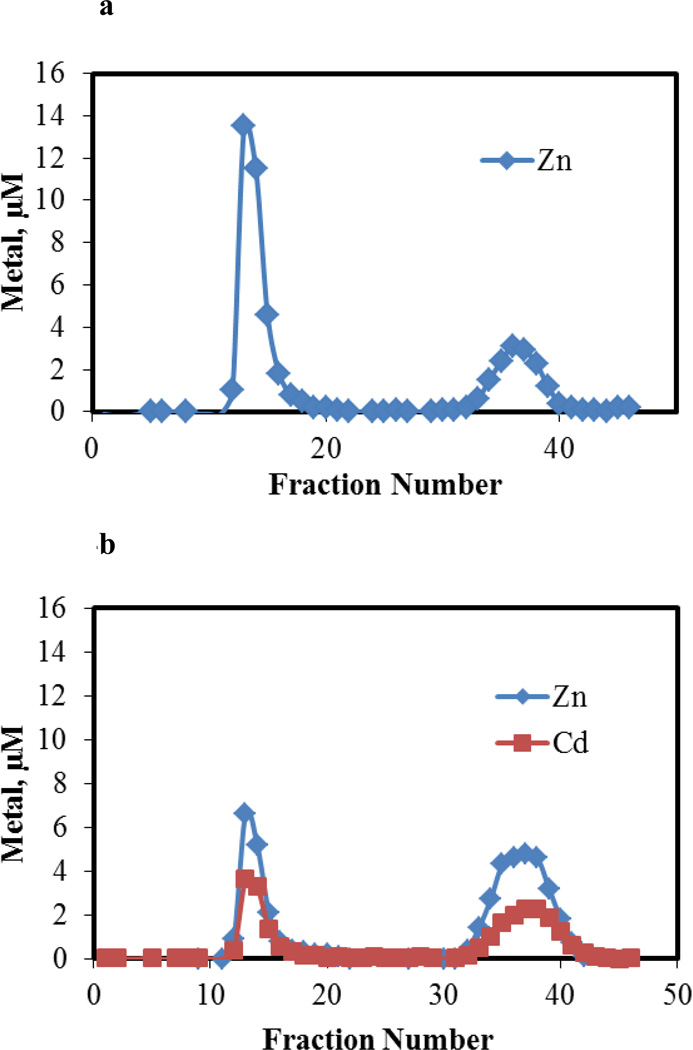

Proteome from pig kidney LLC-PK1 cells was isolated by Sephadex G-75 chromatography and analyzed for Zn2+ by ICP-MS (Figure 1a). A single band of high molecular weight Zn2+ constituted the proteome; no evidence of Zn-metallothionein was obtained (see arrow for location of Zn-MT). To 28 μM Zn2+ present as Zn-proteome, as isolated in Figure 1a and reconcentrated, 23 μM Cd2+ was added. Following gel filtration chromatography, all of the original Zn2+ in the sample plus the added Cd2+ migrated with the proteome (Figure 1b). No Cd-MT was observed. This result was consistent with reaction 4, assuming that the displaced Zn2+ binds to proteomic ligands. The data in Figure 1b were also in agreement with reaction 5. Thus, other experiments were needed to determine the nature of the reactions that had occurred.

Figure 1.

Sephadex G-75 chromatography of supernatant from 5×107 cells. a. Distribution of Zn2+ in sample containing 28 μM Zn2+. Arrow represents location at which Zn-MT elutes. b. Distribution of Zn2+ and Cd2+ after adding 23 μM Cd2+ to 28 μM Zn2+ present in Zn-proteome (a). Reaction time, 60 min.

Properties of the Zn-proteome

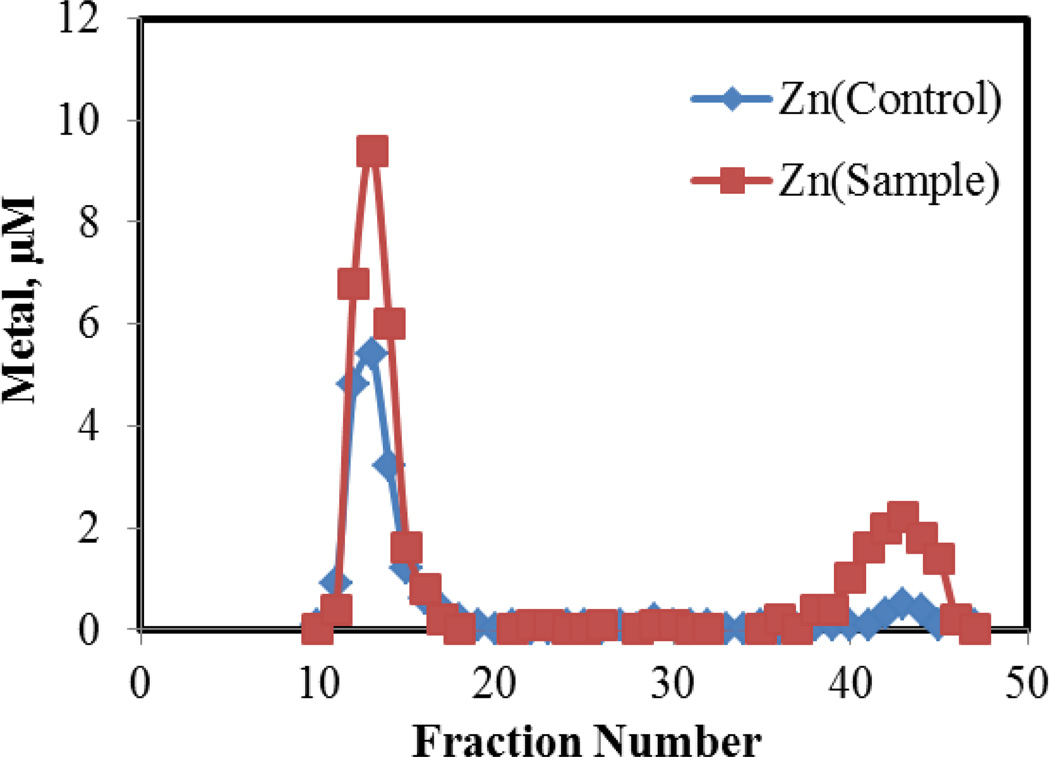

Properties of the native Zn-proteome in Figure 1a were determined as baseline information about the behavior of native-bound Zn2+ within the proteome. Incubation of 10 μM Zn-proteome with the 50 μM ZQ, a Zn2+ sensor, for 30 min followed by Sephadex chromatography revealed a small band of low molecular weight Zn2+ that was assumed to be Zn(ZQ)2 (7 % of proteomic Zn2+) (Figure 2). Upon addition of Zn2+ to Zn-proteome to form Zn-proteome•Zn, ZQ mobilized 60% of the extra Zn2+ as Zn(ZQ)2, which was identified by its fluorescence emission spectrum centered at 490 nm [19]. The reaction leading to the increased formation of Zn(ZQ)2 is described by reaction 6:

| (6) |

ZQ has a substantial, 2:1 (ligand to metal) stability constant for Zn2+ at pH 7 of 1013 [20]. For kinetic or thermodynamic reasons, it is largely unreactive with proteomic Zn2+ bound to native proteins. It does compete for much of the adventitiously bound Zn2+ to form Zn(ZQ)2 and also appears to bind the rest in the form of ternary complexes, which are revealed by a blue-shift in the fluorescence emission spectrum of Zn(ZQ)2 from 490 nm to 470 nm [19]:

| (7) |

Also, as documented in previous studies and below in Figure 5a, 4 μM apometallothionein, which provided 28 μM in Zn2+ binding sites, removed little if any Zn2+ from 28 μM Zn-proteome to form Zn-MT [21,22]. Thus, as with ZQ, Zn-proteome is mostly unreactive with an endogenous ligand, apo-MT, that also has a large binding constant for Zn2+, 1011.2 [16].

Figure 2.

Sephadex G-75 chromatography of Zn-proteome reacted with ZQ. Control (10 μM) Zn2+ as Zn-proteome) and Sample (10 μM Zn-proteome and 10 μM Zn2+ reacted with 50 μM ZQ). Reaction time, 60 min.

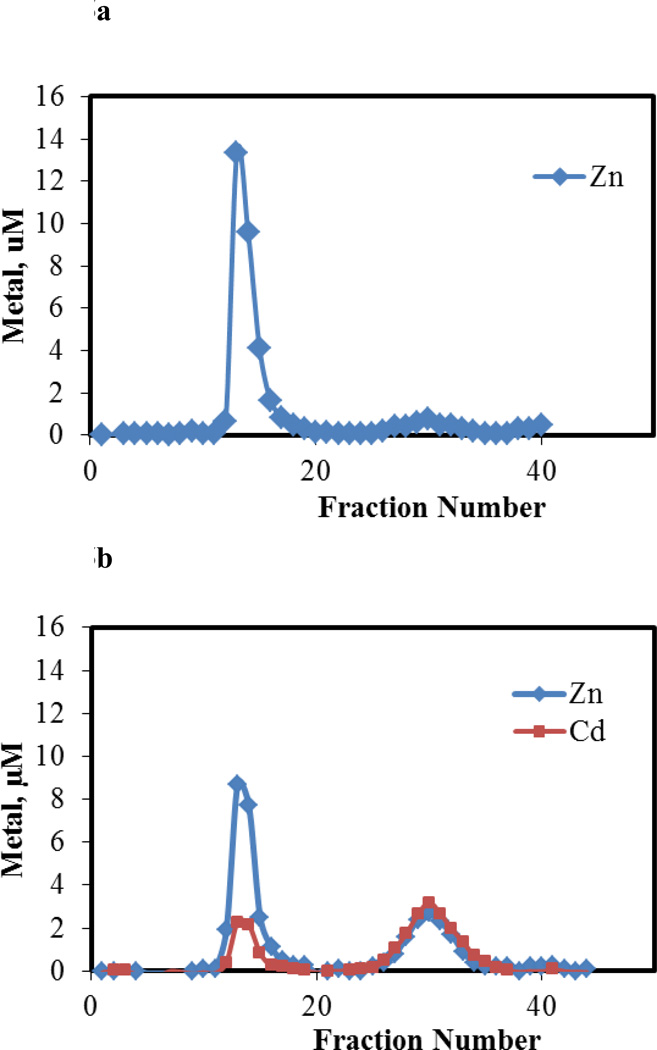

Figure 5.

Sephadex G-75 chromatography of the reaction mixture of apo-MT and Cd-loaded proteome. a. Proteome containing 28 μM Zn2+ and b. proteome with 28 μM Zn2+ and 23 nmoles μM Cd2+ reacted with 4 μM apo-MT (28 μM Zn2+ or Cd2+ binding capacity) in 20 mM Tris buffer, 0.1 M KCl, pH 7.4. Reaction time, 60 min.

Reaction of Cd2+-treated Zn-proteome with ZQ

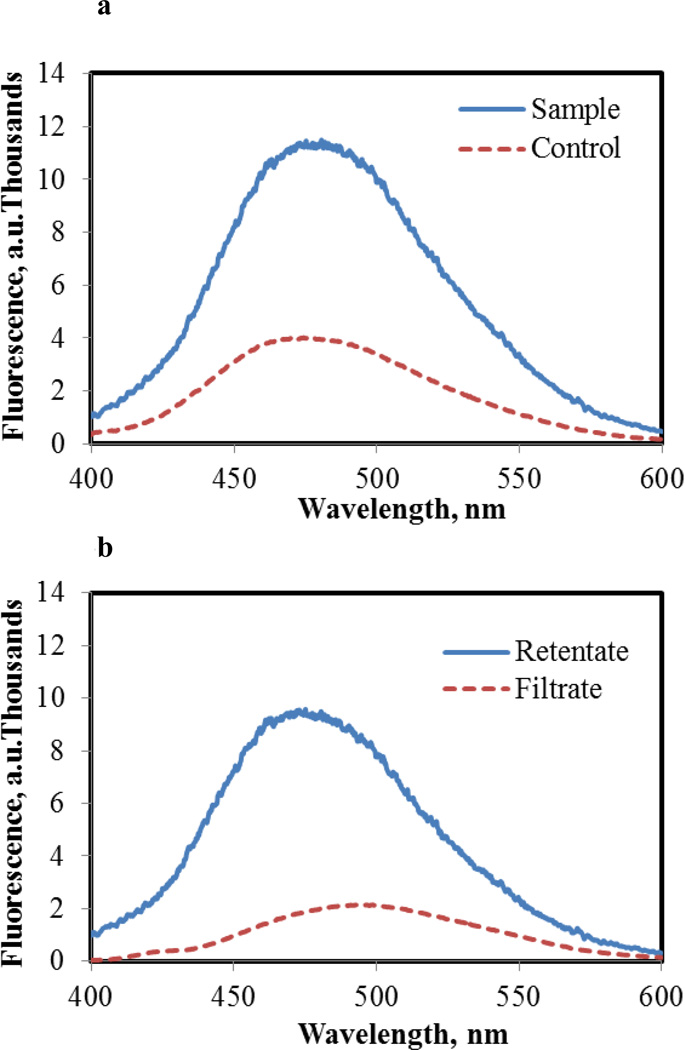

Zn-proteome containing 4.5 μM Zn2+ and 3.2 μM Cd2+ was reacted with 15 μM ZQ in order to determine whether Cd2+ had mobilized Zn2+ from its proteomic binding sites. According to Figure 3a, the presence of Cd2+ increased the emission intensity of ZQ fluorescence above control levels by 2.5 fold and shifted its wavelength maximum from 470 nm toward 480 nm, suggestive of the formation of Zn- or Cd(ZQ)2 which have emission maxima at 490 nm. Upon centrifugal filtration of the reaction mixture to separate proteomic and low molecular weight forms of Zn2+, 25% of the Zn2+ originally bound to the proteome (1.1 μM) appeared in the filtrate. Cd2+ was not detected in this isolate by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. The fluorescence spectrum of the filtrate displayed a wavelength maximum of 490 nm (Figure 3b), consistent with the presence of Zn(ZQ)2. Remaining in the retentate was protein-bound Zn2+ and Cd2+, characterized by a fluorescence spectrum centered at 470 nm (Figure 3b) with much greater intensity than that of the original ZQ-Zn-proteome (Figure 3a, control). As expected, the total fluorescence intensity of separated filtrate and retentate were equal to the initial reaction mixture.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence spectra of Zn-proteome and Cd2+ treated Zn-proteome reacted with ZQACID. a. Control spectrum of Zn-proteome containing 4.5 μM Zn2+ reacted with 15 μM ZQACID in 20 mM degassed Tris buffer pH 7.4 (dashed line). Sample spectrum of Cd2+ exposed Zn-proteome containing 4.5 and 3.2 μM Zn2+ and Cd2+, respectively, reacted with 15 μM ZQACID in 20 mM Tris buffer pH 7.4 (solid line). Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded after 60 minutes with an excitation at 370 nm. b. Fluorescence emission spectra of the filtrate (dashed line) and retentate (solid line) from centrifugal separation of Cd2+ exposed sample in a.

The implication of these results was that Cd2+ had initially displaced Zn2+ from some of its proteomic binding sites (reaction 4). Cd-proteins can form fluorescent ZQ-Cd-proteins with fluorescence spectral maxima similar to but substantially less intense than those of ZQ-Zn-proteins (data not shown). Possibly, ZQ-Cd-proteome structures may have been generated in situ. Moreover, proteome•Zn-ZQ adducts might account for much of the enhanced fluorescence, considering in control experiments that ZQ only mobilized 60% of the adventitiously bound Zn2+. Thus, the contributions that various products made to the fluorescence spectrum of the retentate remained ambiguous.

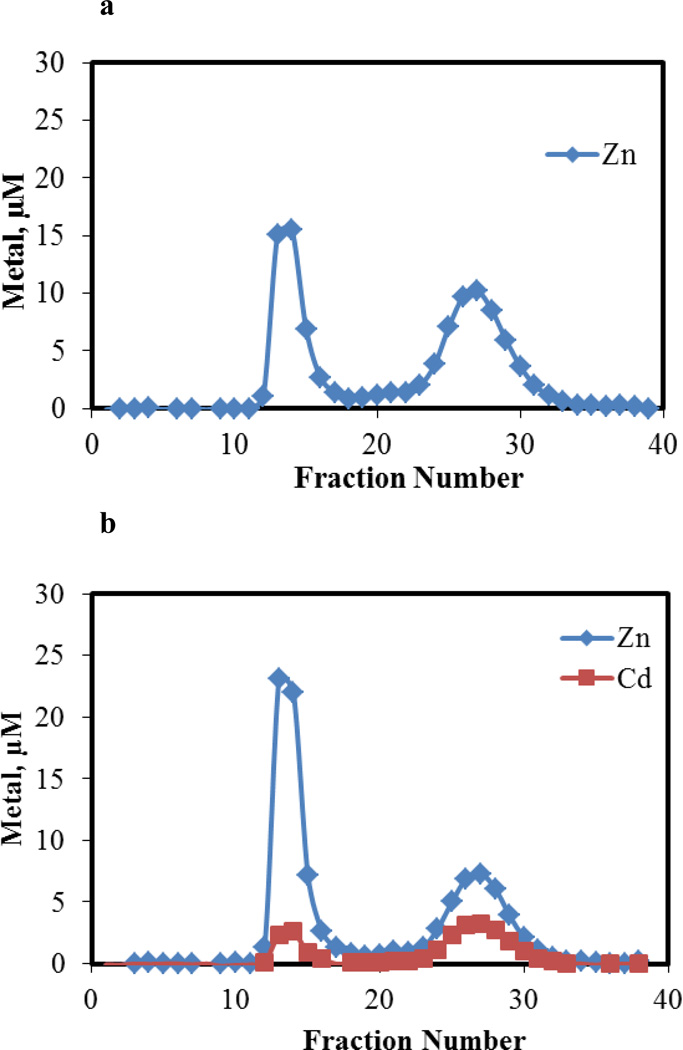

Reaction of Cd2+-treated proteome with EDTA

Another metal binding ligand, EDTA, was employed to probe the proteome modified by Cd2+. A previous study had shown that under approximately stoichiometric conditions EDTA reacts with LLC-PK1 Zn-proteome to extract about 30% of its Zn2+ [22]. That result was repeated in the present experiment. Upon reaction of Zn-proteome (44 μM) with Cd2+ (22 μM), the product was incubated with 86 μM EDTA for 60 min and chromatographed over Sephadex G-75 (Figure 4). The distribution of Zn2+ and Cd2+ within the effluent fractions showed that 60 % of the proteomic Zn2+ and Cd2+ were shifted into the low molecular weight region in association with EDTA. The increased lability of Zn2+ was attributed to reaction 4, consistent with the results obtained with ZQ. Appearance of low molecular weight Cd2+ meant that some but not all of the proteome-bound Cd2+ was also reactive with EDTA.

Figure 4.

Sephadex G-75 chromatography of the reaction mixture of EDTA and Cd-loaded proteome. a. Proteome containing 44 μM Zn2+ and b. Proteome with 44 μM Zn2+ and 22 μM Cd2+ reacted with 86 μM EDTA in 20 mM Tris buffer, 0.1 M KCl, pH 7.4. Reaction time, 60 min.

Reaction of Cd2+-treated Zn-proteome with apo-MT

The reactivity of the Cd2+ treated Zn-proteome was then probed with apo-MT. In this case, apo-MT served as the special, strong metal-binding ligand that is induced within cells upon exposure to Cd2+ [2]. Thus, apo-MT, which provides 28 μM Cd2+ or Zn2+ binding sites, was incubated in an anaerobic cell under nitrogen with the product of the reaction of Cd2+ (25 μM) with Zn-proteome (44 μM). After 60 min the mixture was chromatographed over Sephadex G-75. According to Figure 5b, apo-MT became fully saturated with metals as it sequestered 70% of the protein-bound Cd2+ (15 μM) and a nearly equivalent concentration of Zn2+ (14 μM). A minor fraction of the originally added Cd2+ remained bound to the proteome. These results were consistent with the conclusion that upon reaction with Zn-proteome, Cd2+ displaced Zn2+ in approximate 1 to 1 fashion. Subsequently, apo-MT garnered the liberated Zn2+ and also competed successfully for most of the Cd2+ that was presumably bound to native Zn2+ binding sites. In contrast to ZQ, which only captured labile Zn2+, apo-MT managed to bind both adventitious Zn2+ and Cd2+ that is hypothesized to occupy native Zn2+ binding sites.

| (8) |

These findings support the hypothesis that Cd2+ reacts with the Zn-proteome as shown in reaction 4. They also provide singular evidence that apo-MT can serve as a highly effective competing ligand for Cd2+ bound as Cd-protome.

Reaction of Cd2+-treated Zn-proteome with Zn-MT

The cellular reaction of Cd2+ with the Zn-proteome was further probed with Zn7-MT. The intent was to extend the results obtained with apo-MT to the principal metallo-form of MT that is found in cells. During a 30 min incubation of the reaction mixture with Zn-MT, the more complicated exchange of Cd2+ and Zn2+ between Cd-proteome•Zn and Zn-MT occurred with 1 to 1 stoichiometry with 18.2 μM Zn2+ shifting from Zn7-MT into the proteome band as 18.5 μM Cd2+ moved from the proteome into MT (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sephadex G-75 chromatography of the reaction of Zn-MT and Cd-loaded proteome. a. Proteome containing 44 μM Zn2+ and b. proteome with 44 μM Zn2+ and 25 μM Cd2+ reacted with Zn7-MT (56 μM Zn2+) in 20 mM Tris buffer, 0.1 M KCl, pH 7.4. Reaction time, 60 min.

Based on the quantitative exchange of Cd2+ and Zn2+, it is possible that MT mediated both the removal of Cd2+ from native protein binding sites and its replacement by Zn2+. If so, then, the long proposed hypothesis gains support that Zn-MT provides Zn2+ to reconstitute native Zn-protein functions as it displaces Cd2+ from these modified proteins [23]:

| (9) |

Reaction of cell supernatant with Cd2+

The cell supernatant differs from proteome in that it contains low molecular weight molecules as well as proteins. Principally, with respect to metal binding, it contributes a large concentration of glutathione, thought to be important in Cd2+ trafficking [24]. Cd2+ was reacted with lysate under conditions similar to those used for the reactions with Zn-proteome. As with Zn-proteome alone, Cd2+ reacted exclusively with the proteome; glutathione did not bind to a measureable fraction of the added metal ion (data not shown).

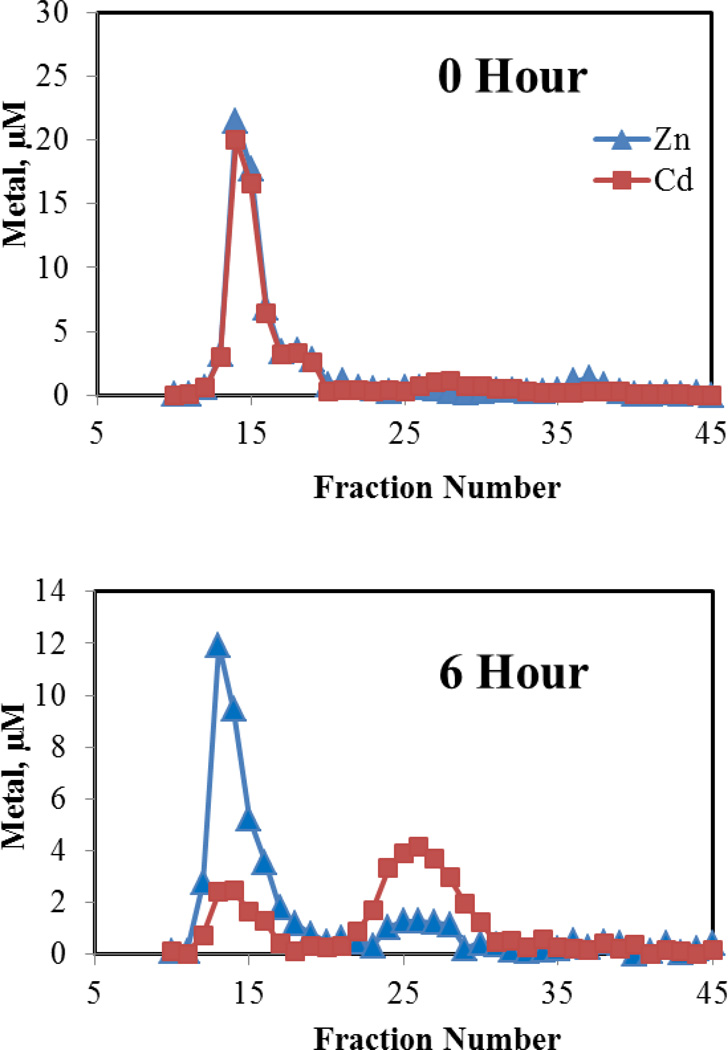

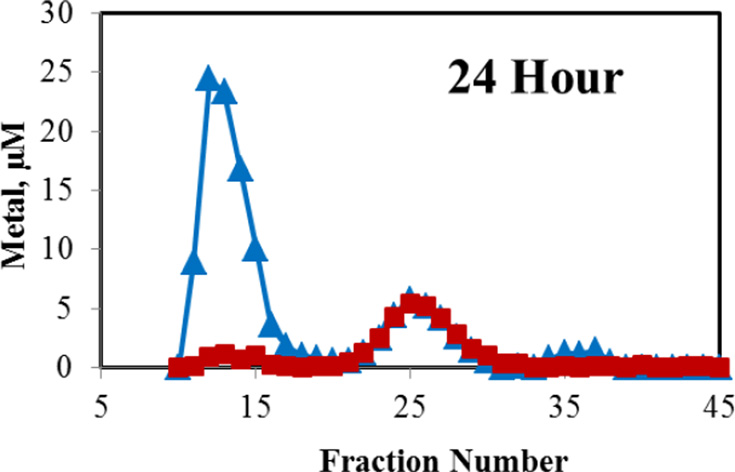

Time-dependent reaction of cells with Cd(pyrithione)2

The in vitro experiments described above demonstrate that upon contact, Cd2+ displaces Zn2+ from native Zn-protein binding sites and that both apo- and Zn-MT can compete to remove Cd2+ from these sites. This provides a model for the cellular behavior of Cd2+. To test this model in cells, the uptake of Cd2+ had to be uncoupled from its subsequent reactions with cellular components. Thus, instead of treating cells with Cd2+ for a lengthy time period such as 24 h, during which many reactions between Cd2+ and cell constituents might occur, cells were exposed for 30 min to Cd2+ and then allowed to respond over time in the absence of further exposure.

LLC-PK1 cells (ca. 108) were incubated with 60 μM Cd2+ in the presence of 3 μM pyrithione for 30 min to effect rapid intracellular accumulation of Cd2+. Pyrithione binds weakly to Cd2+, forming a 2:1, charge-neutral complex that readily diffuses into cells [25]. Then, the medium was replaced and cells were grown under control conditions for 24 h, during which the distribution of Cd2+ and Zn2+ between proteome and MT was determined. Immediate Sephadex G-75 chromatography of the cell supernatant revealed that initially intracellular Cd2+ was solely bound to the proteome (Figure 7a). By 6 h, a sizable peak of Cd2+ associated with MT was already evident (Figure 7b) and by 24 h, almost all of the proteome-bound Cd2+ had been transferred to a growing MT pool (Figure 7c). Notably, mixed metal, Cd,Zn-MT was the product as seen in cells and tissues exposed to Cd2+ [26]. The progressive appearance of Cd,Zn-MT over time parallels what is observed when cells are exposed continuously to Cd2+ for 24 h [27]. Thus, it appears that in cells as well as with isolated proteome, MT can react with Cd-proteome according to reaction 8 or 9.

Figure 7.

Sephadex G-75 chromatography of the intracellular distribution of Cd2+ and Zn2+ after exposure of cells to Cd2+ plus pyrithione. Incubation of about 108 cells with 60 μM Cd2+ and 3 μM pyrithione for 30 min, preparation of cell lysates, followed by chromatography at indicated times.

4. Discussion

Cell and tissue injury caused by toxic metals is commonly multi-faceted. In the case of Cd2+, a so-called Fanconi syndrome results from exposure [3,4]. This conglomerate of nephrotoxic effects involves the depression of a number of Na+-dependent nutrient transport processes that occur in the proximal tubule, including those that resorb glucose, amino acids, phosphate, and calcium from the glomerular filtrate as it is being converted to urine [3,4]. Potentially, a variety of biochemical sites may be involved in the production of these lesions. Generally, attempts to understand Cd2+-based toxicity have focused on one or another of the pathological issues or underlying biochemical outcomes of exposure [10,11]. Commonly, such studies have not defined the chemical sites of binding of Cd2+ that initiate observed perturbations in cellular function. As such, with some exceptions research on the mechanisms of toxicity caused by metals and metalloids lack a strong bioinorganic chemical foundation.

The present study begins an inquiry into approaches and methods that make possible proteomic-level analyses of the reactions of toxic metals and metalloids with cells. In this communication, we queried how Cd2+ interacts with the proteome taken as a whole. The proteome was considered as a chemical reactant and its reaction with Cd2+ characterized. The hypothesis was pursued that Cd2+ favors reaction with native Zn-binding sites within the proteome (reaction 4).

The displacement of Zn2+ from the Zn-proteome by Cd2+ was investigated by assessing whether Zn2+ was mobilized from the proteome upon incubation with Cd2+. The reaction of Cd2+-treated (Zn)-proteome with three competing ligands, ZQ, EDTA, and apo-MT, demonstrated that the presence of Cd2+ within the proteome labilized Zn2+ as measured by the production of Zn(ZQ)2, Zn-EDTA, and Zn-MT, respectively (Figures 3–5). Under stoichiometric conditions of reaction, Cd2+ displaced a large fraction of the Zn2+ contained in the proteome. In turn, this implied that the equilibrium affinity of these sites for Cd2+ exceeded their stability with Zn2+. Since stability constants favor Cd2+ over Zn2+ as the ligand coordination environment shifts from carboxylate, imidazole, and amine toward sulfhydryl groups, the results suggest that, quantitatively, sulfhydryl ligation is prominent within the Zn-proteome as seen in various types of Zn-finger proteins [13].

It was also interesting that the metal ion exchange reactions were kinetically facile. Such comparatively rapid reactions have been reported with Zn-MT and Zn-finger proteins [9,23,28,29]. But Zn-enzymes such as carboxypeptidase, superoxide dismutase, and carbonic anhydrase appear much more sluggish in their metal ion exchange chemistry [30–32].

Apo-MT demonstrates robust affinity for Zn2+ with an apparent stability constant at pH 7 of at least 1011.2 [16]. Nevertheless it only removed 0–10% of Zn2+ from the Zn-proteome (Figure 5a). This finding corroborated an earlier observation that apo-MT can co-exist with the Zn-proteome in vivo or in vitro [22]. In comparison, under similar conditions a variety of small metal chelating agents sequester 25–30% of proteomic Zn2+. The reactivity of the Cd-proteome with apo-MT was remarkable when contrasted with the inertness of the native Zn-proteome to reaction with this competing ligand. An earlier study showed that rabbit apo-MT readily extracted Cd2+ from Cd-carbonic anhydrase and did so faster than EDTA [33]. Moreover, a synthetic peptide containing residues 49–61 of MT and the last 4 cysteinyl sulfhydryl groups of the sequence rapidly and stoichiometrically extracted Cd2+ from the protein [33,34]. It was argued that this peptide might serve as a model for cellular reaction of apo-MT with Cd-proteins. Being at the C-terminus of the MT peptide, where there is least steric hindrance to ligand substitution reactions and containing the only four contiguous cysteinyl sulfhydryl groups that bind to the same Cd2+ in Cd7-MT, this end of the molecule is best suited to undergo direct reaction with sites that contain Cd2+.

Successful inter-protein metal ion exchange reaction between Cd-proteome•Zn and Zn-MT was observed for the first time in this study (Figure 6). Previously, it had been shown that reaction of Zn7-MT with Cd-tramtrack, a transcription factor, restored its capacity to bind to its cognate DNA sequence [35]. Conceivably, the reaction involves the direct exchange of Cd2+ and Zn2+,

| (10) |

If so, that would mean that protein functionality was restored to at least some of the proteins undergoing Cd2+-Zn2+ exchange. This is a long standing hypothesis, based on the finding in mixed metal Cdn,Zn7-n-MT that Cd2+ and Zn2+ tend to be segregated between the two metal-thiolate clusters [23,26,36]. It was contended that the C-terminal domain maintains Cd2+ in an inert form unavailable to sensitive sites in the cell and the N-terminal domain binds more reactive Zn2+ that might exchange metals with other sites. The present results do not discriminate between reaction 10 and another possible outcome,

| (11) |

followed possibly by

| (12) |

in which apo-Zn-proteins are reconstituted with Zn2+.

In principle, reactions 10 and 11 involve two fully coordinated sites that are associated with bulky proteins and are, thus, the most difficult to accomplish from a mechanistic stand point. Nevertheless, such reactions recall a signature reaction of MT in which these two metal ions are exchanged between different MT molecules and different domains according to the reaction (13) in order to achieve the mixed metal MT species observed in cells [36]:

| (13) |

The MT concentration-dependence of the reaction portrayed in Figure 6b was not determined. Still, under stoichiometric conditions, not all of the proteomic Cd2+ was shifted into the MT pool. It is likely that the residual Cd2+ bound within the proteome represents binding to sites that are unreactive with MT and contribute to cytotoxicity. As methods are developed to fractionate and analyze the Cd-proteome, attention will be focused on this pool of Cd2+.

Proteomic studies were also conducted with whole cell supernatant that differs from proteome by the presence of glutathione. GSH has been considered an important contributor to cellular protection against Cd2+ toxicity [22]. Its presence does not alter the capacity of Cd2+ to react with the proteome.

To complement the chemical studies with a comparable in vivo model of Cd2+ exposure, cells were incubated with Cd2+ and pyrithione for 30 min during which Cd2+ was transported efficiently from the extracellular medium into the cells by pyrithione, which forms a 2:1 complex with Cd2+ that is both charge neutral and lipophilic. At the end of this period, Cd2+ was associated with the proteome as seen in vitro (Figure 7). Over time, as MT synthesis was induced, an increasing concentration of Cd,Zn-MT appeared and the proteomic pool of Cd2+ declined. These results revealed for the first time that intracellular MT can compete directly and effectively with Cd2+ associated with the proteome just as it does in vitro. It has been widely hypothesized that this type of reaction occurs in cells, but heretofore it could not be distinguished from the possibility that newly synthesized MT only intercepted in-coming Cd2+ before it reacted with the proteome.

The cellular experiment matched porcine Cd-proteome and MT, whereas in the Cd-proteomic reactions, rabbit MT was employed. That the in vivo and in vitro reactions yielded qualitatively similar results both validates the choice of rabbit MT in this study and suggests that on a proteomic scale of analysis, small differences in non-cysteinyl amino acids within MTs do not play a major role in MT reactivity [17,18].

The cumulative results of this paper support the hypothesis that Cd2+ can undergo widespread reaction with the Zn-protein through metal ion exchange. In turn, it is hypothesized that facets of the diverse sorts of cell injury described for Cd2+ are rooted in this type of reaction. In addition, given the major role of sulfhydryl-containing sites in the trafficking of Cu1+, consideration needs to be given to perturbation of the Cuproteome by Cd2+ [37].

The lability of proteomic Zn2+ to metal ion substitution by Cd2+ suggests that other toxic metallic species might act through their reaction with elements of the Zn-proteome. For example, preliminary experiments such as those described above, indicate that Pb2+ can also undergo reaction 4 and replace Zn2+ in proteomic binding sites. Indeed, the apparent large role of cysteinyl sulfhydryl ligands in binding proteomic Zn2+ strengthen the hypothesis that heavy metal and metalloid species may target the Zn-proteome.

The analytical methodology used in this study, gel filtration chromatography in combination with metal analysis by atomic absorption spectrophotometry or inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry has been used widely to determine the concentration of metals bound collectively to the proteome [38]. In order to reveal metals bound to individual proteins, much more refined protein separation is required. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic (PAGE separation of proteome combined with laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry has shown promise [39]. But the lack of a PAGE technique that both provides high resolution protein separation and retains proteins in their native states with bound metals has hindered progress [39,40]. The authors have devised a modification of sodium dodecyl sulfate PAGE that meets both of these requirements and will soon report on its use in understanding the reaction of Cd2+ with the Zn-proteome.

Highlights of this manuscript include the following.

Novel experiments reveal the reaction of the Zn-proteome with Cd2+.

Cd2+ displaces Zn2+ from Zn-proteins in approximately stoichiometric fashion.

Much of the Zn-proteome can be converted to Cd-proteome.

Both apo-metallothionein (MT) and Zn7-MT bind Cd2+ from Cd-proteome.

Cellular Cd-proteome reacts with MT following the induction of MT.

Acknowledgements

the authors appreciate the support of NIH grants ES-04026, ES-04184 and GMS-85114.

Abbreviations

- Cd,Zn-MT

metallothionein with Cd2+ and Zn2+ bound to it

- DPBS

Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- ICP-MS

inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- MT

metallothionein

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- ZQ

Zinquin, acid form

- Zn-MT

metallothionein with Zn2+ bound to it

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Petering DH, Kothini R, Meeusen J, Rana U. In: Cellular and Molecular Biology of Metals. Zalups RK, Koropatnick J, editors. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2010. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petering DH, Krezoski S, Tabatabai N. Met. Ions in Life Sci. 2009;5:353–398. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johri N, Jacquillet G, Unwin R. Biometals. 2010;23:783–792. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9328-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thévenod F, Lee WK. Met. Ions Life Sci. 2013;11:415–490. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5179-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabatabai NM, Blumenthal SS, Petering DH. Toxicology. 2005;207:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kothinti RK, Blodgett AG, Petering DH, Tabatabai NM. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010;244:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi E, Okubo Y, Suwazono Y, Kido T, Nogawa K. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2002;22:431–436. doi: 10.1002/jat.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Liu Y, Habeebu SS, Klaassen CD. Toxicol. Sci. 1998:197–203. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kothinti R, Blodgett A, Tabatabai NM, Petering DH. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010;223:405–412. doi: 10.1021/tx900370u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thévenod F. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009;238:221–239. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao W, Liu Y, Templeton DM. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009;238:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laity JH, Lee BM, Wright PE. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Razin SV, Borunova VV, Maksimenko OG, Kantidze OL. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2012;77:217–226. doi: 10.1134/S0006297912030017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:196–201. doi: 10.1021/pr050361j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Namdarghanbari M, Wobig W, Krezoski S, Tabatabai MN, Petering DH. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2011;16:1087–1101. doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0823-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Namdarghanbari MA, Meeusen J, Bachowski G, Giebel N, Johnson J, Petering DH. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2010;104:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunziker PE, Kaur P, Wan M. Biochem. J. 1995;306:265–270. doi: 10.1042/bj3060265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang M-C, Pan PK, Zheng TF, Chen NC, Peng JY, Huang PC. Gene. 1998;211:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowakowski AB, Petering DH. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:10124–10133. doi: 10.1021/ic201076w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasir MS, Fahrni CJ, Suhy DA, Kolodsick KJ, Singer CP, O'Halloran TV. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1999;4:775–783. doi: 10.1007/s007750050350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petering DH, Zhu J, Krezoski S, Meeusen J, Kiekenbush C, Krull S, Specher T, Dughish M. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2006;231:1528–1534. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rana U, Kothinti R, Meeusen J, Tabatabai NM, Krezoski S, Petering DH. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otvos J, Petering DH, Shaw CF., III Comments on Inorg. Chem. 1989;9:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wimmer U, Wang Y, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5715–5727. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forbes IJ, Zalewski PD, Hurst NP, Giannakis C, Whitehouse MW. FEBS Lett. 1989;247:445–447. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otvos JD, Armitage IM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1980;77:7094–7098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumenthal S, Lewand D, Krezoski SK, Petering DH. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1996;136:220–228. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ejnik J, Shaw CF, 3rd, Petering DH. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:6525–6534. doi: 10.1021/ic1003148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quintal SM, dePaula QA, Farrell NP. Metallomics. 2011;3:121–139. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00070a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman JE, Vallee BL. J. Biol. Chem. 1961;236:2244–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carrico RJ, Deutsch HF. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:723–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coleman JE. Biochemistry. 1965;4:2644–2655. doi: 10.1021/bi00888a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ejnik J, Muñoz A, Gan T, Shaw CF, 3rd, Petering DH. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1999;4:784–790. doi: 10.1007/s007750050351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz A, Laib F, Petering DH, Shaw CF., 3rd J Biol Inorg Chem. 1999;4:495–507. doi: 10.1007/s007750050335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roesijadi G, Bogumil R, Vasák M, Kägi JH. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:17425–17432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nettesheim DG, Engeseth HR, Otvos JD. Biochemistry. 1985;24:6744–6751. doi: 10.1021/bi00345a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubino JT, Franz KJ. J Inorg Biochem. 2012;107:129–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gómez-Ariza JL, Jahromi EZ, González-Fernández M, García-Barrera T. J. Gailer. Metallomics. 2011;3:566–577. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00037c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sussulini A, Becker JS. Metallomics. 2011;3:1271–1279. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00116g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnett JP, Scanlan DJ, Blindauer CA. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012;402:3311–3322. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-5743-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]