Abstract

Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL or Batten disease) is a neurodegenerative disorder caused by mutation in CLN3. Defective autophagy and concomitant accumulation of autofluorescence enriched with mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c were previously discovered in Cln3 mutant knock-in mice. Here we show that treatment with lithium reduces numbers of LC3-positive autophagosomes and accumulation of LC3-II in Cln3 mutant knock-in cerebellar cells (CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8). Lithium, an inhibitor of GSK3 and IMPase, reduces the accumulation of mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c and autofluorescence in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, and mitigates the abnormal subcellular distribution of acidic vesicles in the cells. L690,330, an IMPase inhibitor, is as effective as lithium in restoring autophagy in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells. Moreover, lithium or downregulation of IMPase expression protects CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells from cell death induced by amino acid deprivation. These results suggest that lithium overcomes the autophagic defect in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells probably through IMPase, thereby reducing their vulnerability to cell death.

Introduction

Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL or Batten disease) is an autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder caused by various mutations in CLN3 gene. The clinical features of this disease usually appear in young children, around 6–10 years of age, with the onset of vision loss, seizures and motor neuron loss, and ultimately lead to death by 18–30 years of age (Santavuori, 1988). The pathological marker of JNCL is the accumulation of autofluorescence rich in subunit c of the mitochondrial ATP synthase complex within lysosomes and autophagosomes in central nerve system neurons (Cotman et al. 2002; Cao et al. 2006). In an earlier study, a Cln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 knock-in mouse model of JNCL exhibited a marked deficiency in motor coordination (Cotman et al. 2002). Moreover, atrophy within the cerebellum of JNCL patients, selective neuronal loss within the mature fastigial pathway and alterations within the developing cerebellum all suggest that deterioration within the cerebellum contributes to the deficits in motor coordination seen in JNCL patients (Autti et al. 1996; Weimer et al. 2009).

CLN3 is a multi-transmembrane protein mainly localized in lysosomes/endosomes and synaptic vesicles (Haskell et al. 2000). It is reportedly associated with various lysosomal events, including pH regulation (Pearce et al. 1999a; Pearce et al. 1999b; Golabek et al. 2000), arginine transport (Kim et al. 2003; Ramirez-Monteallegre and Pearce, 2005), autophagic maturation (Cao et al. 2006), regulation of the fodrin cytoskeleton and Na+-K+ ATPase (Uusi-Rauva et al. 2008) and cell death (Chang et al. 2007; Persaud-Sawin and Boustany, 2005). Despite extensive study, however, details of the molecular events involved in CLN3 function are not yet clear.

Macroautophagy, referred to hereafter as autophagy, is thought to be a major process by which damaged cellular compartments and protein aggregates are cleared from cells, and its malfunction is thought to be a cause of human disease (Rubinsztein, 2006). In particular, lysosomal events are important for maturation of autophagic vacuoles (Mizushima et al. 2002). In that regard, maturation of autophagic vacuoles in Cln3 mutant knock-in mice show defects that are likely associated with the predicted role of CLN3 in lysosomes (Cao et al. 2006). Moreover, autophagic immaturity caused by Cln3 deletion may result in accumulation of autofluorescence and may be linked to degeneration and death of the affected neurons (Cao et al. 2006). However, there have been no reports on how to ameliorate or reduce such pathologic accumulation within lysosomes.

Lithium compound exerts therapeutic or protective effects in a variety of neuronal disease models (Chuang, 2005), including brain ischemia (Cappuccio et al. 2005), Alzheimer’s disease (Phiel et al. 2003), affective bipolar disease (Manji and Lenox, 1998) and kainate-induced neuronal cell death (Busceti et al. 2007). Lithium is well known as an inhibitor of GSK-3β Also, lithium inhibits IMPase which dephosphorylates myo-inositol monophosphate to generate free myo-inositol in turn, decreasing the production of the PI-related second messengers, such as myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol (Berridge et al. 1989; Coyle and Duman, 2003). This inhibitory effect of IMPase by lithium increases the cellular clearance of mutant huntingtin fragments and protease-resistant prion protein by induction of autophagy (Sarkar et al. 2005; Heiseke et al. 2009). These observations prompted us to examine the effect of lithium, as an autophagy modulator, on the defective autophagy observed in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells, an in vitro model of JNCL. We found that lithium improves the defective autophagy in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells via IMPase inhibition.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), G418 (200 µg/ml) and 24 mM KCl at 33°C for maintenance of the immortal phenotype (Fossale et al. 2004). Stable SH-SY5Y transfectants were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were transfected with appropriate vectors [pcDNA, pCLN3 or pCLN3 AS (anti-sense)] using LipofectAMINE reagent (Invitrogen) and selected with G418 (1 mg/ml) for 2 weeks to generate stable clones as previously described (Chang et al. 2007). Lymphoblastoid cells from control and JNCL patients (homozygous 1.02-kb deletion) were kindly provided by Dr. D. Pearce (University of Rochester, USA) and were cultured in RPMI1640 (Life Technologies Inc.) supplemented with 15% FBS.

Plasmid construction

To construct IMPase1 and IMPase2 shRNAs, forward and reverse 64-nucleotide fragments containing the 19-nucleotide mouse IMPase1/2 dsRNA hairpin coding sequence (5'- AGC CAA AGA AAT TGA GAT A-3' corresponding to mouse IMPase1 840–858) or (5'-TGA AAG TAT TCC TGA GCA A-3' corresponding to mouse IMPase2 736–754) as an inverted repeat separated by a 9-nucleotide-long hairpin region were annealed and inserted into the BglII/HindIII sites of pSUPER vector (Oligo Engine). Vectors for pCLN3, pCLN3 AS (anti-sense), pCLN3 Δ1 (1–153), −Δ2 (1–263) and −Δ3 (154–438) were described previously (Chang et al. 2007).

RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was purified from CbCln3+/+ or CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells using TRIZOL® reagent (Invitrogen). After synthesis of cDNA, the following synthetic primer sets were used for PCR (25 cycles): IMPase1, 5'-TTG GGA TTG TGT ACA GCT GTG TGG-3' (forward, 410–433) and 5'-CAG GGA CAG CAA GGA TGA CAC T-3' (reverse, 913–934).

Western blot analysis

Cells were lyzed with sampling buffer (10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, pH 6.8) and same amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blotting using IMPase1 or IMPase2 antibodies (Ohnishi et al. 2007).

Live/Dead cell assay

Cells were loaded with the fluorescent dyes calcein-AM (0.5 µM) and ethidium homodimer (0.5 µM) for 15 min at 37°C (Live/Dead assay, Invitrogen) and then visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus). The percentage of dead cells (normalized to total) was calculated as (number of dead cells)/(total number of cells) × 100.

Whole brain extracts preparation

Whole brains from Cln3 knockout or aged-matched wild-type mice were kindly provided by Dr. D. Pearce (University of Rochester, USA). Tissue extraction was described previously (Chang et al. 2007).

Assessment of autophagy

SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with pGFP-LC3 using LipofectAMINE reagent and selected with G418 (1 mg/ml) for 2 weeks to generate stable transfectants (SH-SY5Y-LC3). To assay autophagy, the percentage of GFP-LC3-positive cells was determined by counting cells showing more than five GFP-LC3 dots per cell among the total number of GFP-positive cells and the percentage of red-only puncta (mCherry) was calculated by counting cells showing mCherry-only signal among the total fluorescent-positive cells [yellow (colocalization) + mCherry] (n > 30 cells). LC3-II levels were assessed by Western blotting using anti-LC3 antibody (Novus Biologicals) (Noh et al. 2009). LC3-II and Tubulin signals on Western blots were quantified by densitometric analysis using Gene Tools software (Syngene).

Mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c inclusion assay

CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells (2.5×105 cells/100 mm plate) were incubated at 33°C until they reached 70–75% confluence, after which cells were treated with or without LiCl in Cbc growth medium (without KCl) every 3rd or 4th day. On day 14, cells were replated in 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells/well and the incubation with or without LiCl was continued for an additional 24 h. Cells were then fixed and processed for immunostaining with anti-mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c antibody. Plates were imaged on an automated microscope (ImageXpress Micro high content imaging system from Molecular Devices) using 10× magnification. Replicates of at least 12 wells per treatment were used and each well was imaged in 3 areas. The mean numbers of small (1.5–3 µm) and large (3–8 µm) vesicles/cells were counted for each focused image using Transfluor module of MetaXpress Image Analysis software.

Fluorescence and confocal microscopy

CbCln3+/+, CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 and SH-SY5Y cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5×104 cells per well and grown overnight at 33°C (cerebellar cells) or 37°C (SH-SY5Y cells). The growth media were then exchanged with fresh pre-warmed media containing 500 nM Lysotracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen) and the cells were incubated for an additional 20 min. Once labeled, the cells were immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min and then visualized under an I×71 inverted fluorescence microscope using a 40× objective and DP Controller software (Olympus). For detection of the mCherry-GFP-LC3 or GFP-LC3 signal, cells grown on cover slips and transfected with the indicated plasmid were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then examined under an Eclipse TE 2000-U confocal microscope equipped with a 100× oil immersion objective (Nikon) and an UltraVIEW confocal imaging system (Perkin- Elmer). The autofluorescent signal was observed at excitation 488 nm/emission 520 nm under LSM 510 NLO confocal microscope using 40× magnification and Zeiss LSM image browser software (Carl Zeiss). To quantify the autofluorescence, the percentage of autofluorescence-positive cells was determined by counting at least 22 cells per image.

Reagents

Compounds used in cell culture were SB216763 (Tocris), LiCl (Sigma-Aldrich, purity > 99%), 0.2 µM rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and L-690,330 (Tocris).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot. All data are expressed as means ± S.D. Results comparing three or more samples were analyzed using ANOVA and Bonferroni tests; comparisons between two samples were analyzed using Student’s ttests. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Lithium reduces the accumulation of autophagic vacuoles caused by CLN3 deletion

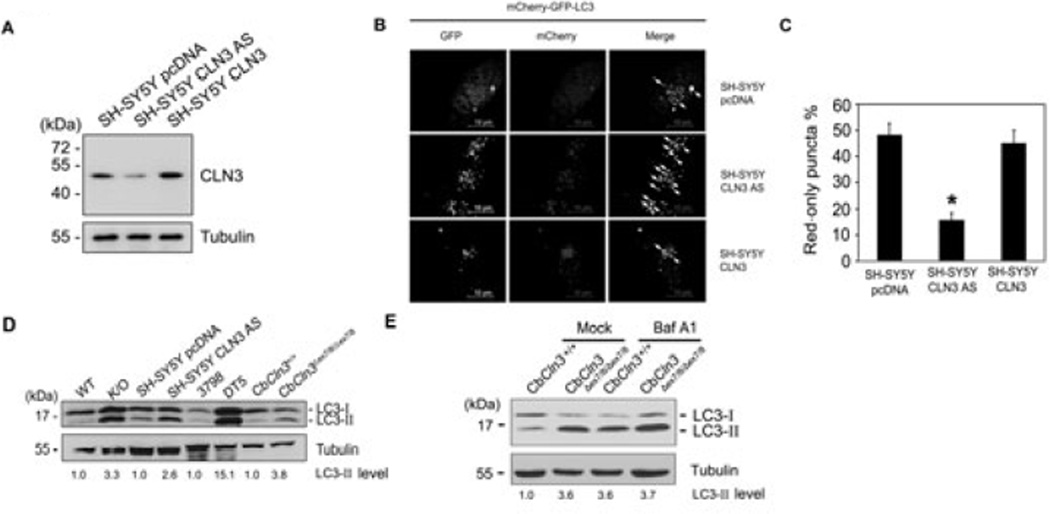

To investigate a role of CLN3 in autophagy of neuronal cells, we established stable human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y transfectants expressing anti-sense (AS) (SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells) or wild-type cDNA of CLN3 (SH-SY5Y CLN3 cells) (Fig. 1A). Autophagic processes were then examined in these cells after transient transfection with mCherry-GFP-LC3, a double fluorescent LC3 which is labeled with acid-labile GFP and acid-stable mCherry and is frequently used to differentiate autophagosome formation from maturation. For example, if autophagosomes are matured into autolysosomes, there is a significant number of mCherry-only puncta. On the other hand, if autophagic process is impaired at autophagy maturation, most puncta show both red and green signals (Kimura et al. 2007). We found that the downregulation of CLN3 expression seen in SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells enhanced both the mCherry and GFP signals, and increased colocalization of the two signals compared to control SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1B and C). Western blotting using anti-LC3 antibody also revealed that levels of LC3-II, an autophagosome-associated form of LC3, were elevated in extracts from SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells (Fig. 1D). Similar increases in LC3-II were observed in extracts of whole brain from Cln3 knock-out mice (K/O), lymphoblastoid cells from JNCL patients (DT5) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. Conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II is enhanced by CLN3 deficiency.

(A) Generation of CLN3 knockdown cells. SH-SY5Y cells were stably transfected with control pcDNA (SH-SY5Y pcDNA), pCLN3 AS (SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS; anti-sense cDNA of CLN3) or pCLN3 (SH-SY5Y CLN3), after which CLN3 expression was assessed by Western blotting with anti-CLN3 antibody. (B and C) Defective autophagic maturation in CLN3 knockdown cells. SH-SY5Y pcDNA, SH-SY5Y CLN3 or SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells were transiently transfected with mCherry-GFP-LC3 for 48 h and then examined under a confocal microscope. Arrows indicate cellular colocalization of mCherry and GFP (B). The numbers of cells showing only red fluorescence in B were quantified and are represented as bars (means ± S.D., n > 30 cells). Asterisk indicates a significant difference from control (p < 0.05) (C). (D) CLN3 deletion increases LC3-II levels. Whole brains extracts from Cln3 knock-out (K/O) mice and age-matched control (WT) mice, cell extracts from SH-SY5Y pcDNA and SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells, lymphoblastoid cell extracts of JNCL patients (DT5) and age-matched controls (3798), and cerebellar cell extracts from CbCln3+/+ (wild-type) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 (homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8) mice were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-LC3 and anti-Tubulin antibodies. LC3-II levels on the blot were quantified by densitometric analysis and normalized by those of Tubulin. Their relative ratios to the control (WT) are represented (LC3-II level). (E) Defective autophagic maturation in Cln3 knock-in cerebellar cells. CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were left untreated (Mock) or incubated with 20 nM bafilomycin A1 (Baf A1) for 2 h. Cell extracts were then prepared and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-LC3 antibody. The LC3-II signals on the blot were quantified as described in D.

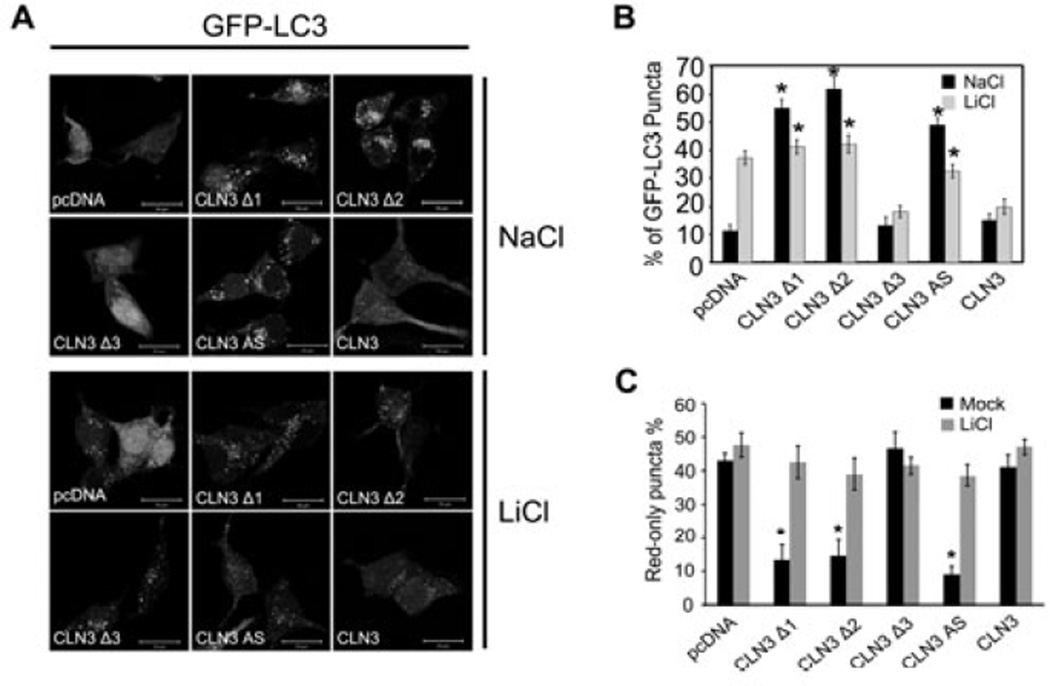

When we used bafilomycin A1, a V-ATPase inhibitor, to monitor autophagic flux, we found that bafilomycin A1 enhanced LC3 conversion in CbCln3+/+ cerebellar cells, but not much in CbCln3 Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells (Fig 1E), indicating that the increase of LC3-II level in CLN3-deficient cells is mainly due to the inhibition of autophagic degradation. In addition, we found that the formation of LC3 dots was induced by ectopic expression of CLN3 Δ1 or Δ2, two C-terminal deletion mutants frequently seen in JNCL, but not by expression of CLN3 Δ3, an N-terminal deletion mutant (Fig. 2A and B). Thus, CLN3 Δ1 and Δ2 may function as dominant negative mutant to increase LC3 dot formation. Consistent with the previous report (Cao et al. 2006), CLN3 deficiency and CLN3 mutations associated with JNCL appear to be linked to abnormal autophagic maturation.

Fig. 2. Lithium reduces the accumulation of LC3 dots resulting from CLN3 mutation.

(A) Photomicrograph showing the effect of CLN3 deletion on LC3 dot formation. SH-SY5Y-LC3 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA, pCLN3Δ1 (1– 153), pCLN3Δ2 (1–263), pCLN3Δ3 (154–438), pCLN3 AS or pCLN3 for 24 h and then examined for LC3 dot formation. (B) Inhibition of LC3 dot formation by lithium. SH-SY5Y-LC3 cells were transiently transfected as in (A) and then treated with 10 mM NaCl or 10 mM LiCl for 24 h. The formation of GFP-LC3-positive dots was assessed using a fluorescence microscope. Bars indicate means ± S.D. (n > 30 cells). Asterisks indicate significant difference from control (p < 0.05). (C) SH-SY5Y cells were transiently cotransfected with mCherry-GFP-LC3 and either pcDNA, pCLN3Δ1 (1–153), pCLN3Δ2 (1–263), pCLN3Δ3 (154–438), pCLN3 AS or pCLN3 for 24 h and then left untreated (Mock) or treated with 10 mM LiCl for 24 h. The numbers of cells showing only red fluorescence were counted under a confocal microscope as described in Materials and methods. Bars indicate means ± S.D. (n > 30 cells). Asterisks indicate significant difference from control (p < 0.05)

We tested the effect of lithium on autophagosome accumulation induced by CLN3 deletion. Lithium effectively induced GFP-LC3 dot formation in SH-SY5Y-LC3 cells expressing GFP-LC3 (Fig. 2A and B) (Sarkar et al. 2005). By contrast, treatment with lithium reduced the number of GFP-LC3 dots to the control levels in SH-SY5Y cells expressing CLN3 Δ1 or Δ2, or in SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells. This inhibitory effect of lithium was not observed in SH-SY5Y cells expressing wild-type CLN3 or CLN3 Δ3. We further investigated the effect of lithium on autophagic maturation by employing mCherry-GFP-LC3. Most of GFP-LC3 signals overlapped with those of mCherry-LC3 in SH-SY5Y cells expressing CLN3 Δ1 or Δ2, or in SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells, but not much in SH-SY5Y control cells and SH-SY5Y expressing CLN3 Δ3 (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Fig. 2C). Interestingly, treatment with lithium reduced the colocalization of GFP-LC3 and mCherry-LC3 and increased the numbers of red-only puncta in SH-SY5Y cells expressing CLN3 Δ1 or Δ2, or in SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells, which was similar to that observed in control cells.

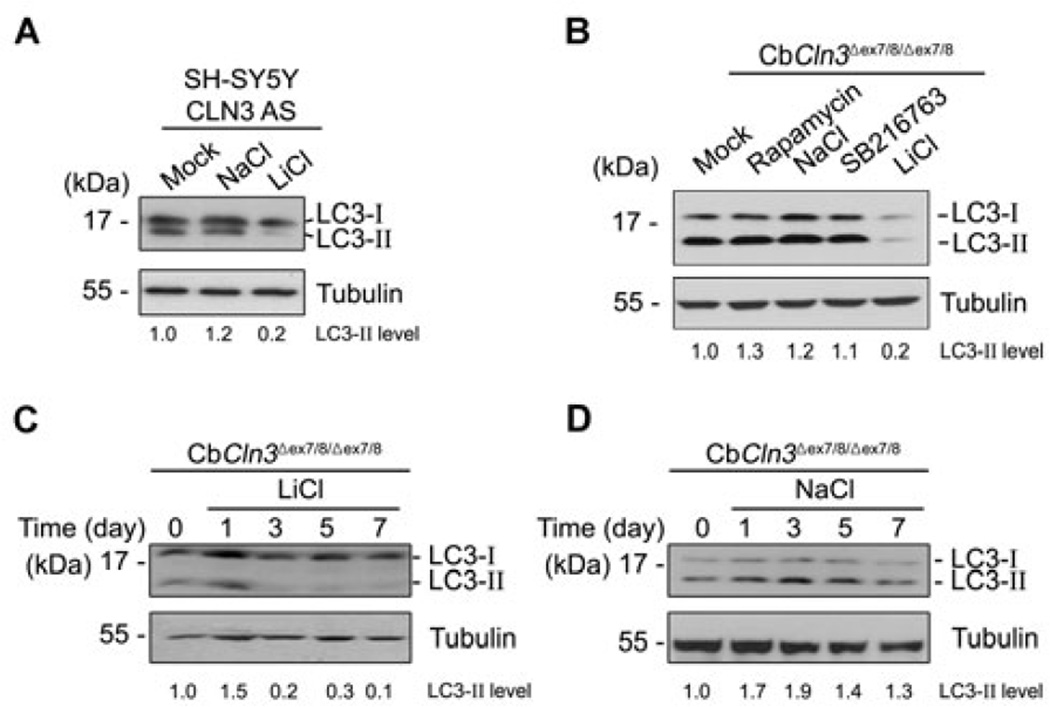

Western blot analysis showed that lithium reduced LC3-II levels in SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells (Fig. 3A) and CbCln3 Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells (Fig. 3B). Indeed, treatment with lithium completely eliminated LC3-II level in CbCln3 Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells within 3 days (Fig. 3C), while NaCl was used as a negative control and did not show such effects (Fig. 3D). Conversely, rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR, increased LC3-II levels in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, though SB216763, a GSK3 inhibitor, had no effect (Fig. 3B). We confirmed the inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin using Western blotting (Data not shown). Taken together, these findings suggest that lithium may function to modulate the maturation of autophagosomes in CLN3-deficient cells.

Fig. 3. Lithium reduces LC3-II level in SH-SY5Y CLN3 knockdown and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells.

(A) SH-SY5Y CLN3 AS cells were left untreated (Mock) or treated for 7 days with 10 mM NaCl (control) or 10 mM LiCl. Cell extracts were then prepared and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-LC3 antibody. (B) CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were left untreated (Mock) or treated for 7 days with 0.2 µM rapamycin, 10 mM NaCl (control), 10 µM SB216763 (GSK inhibitor) or 10 mM LiCl and then analyzed as in (A). (C and D) CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were treated with 10 mM LiCl (C) or 10 mM NaCl (D) for the indicated times and analyzed as in (A). The LC3-II signals on the blot were quantified as described in Fig. 1D.

Lithium restores perinuclear localization of acidic vesicles and autophagy maturation in CbCln3 Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells

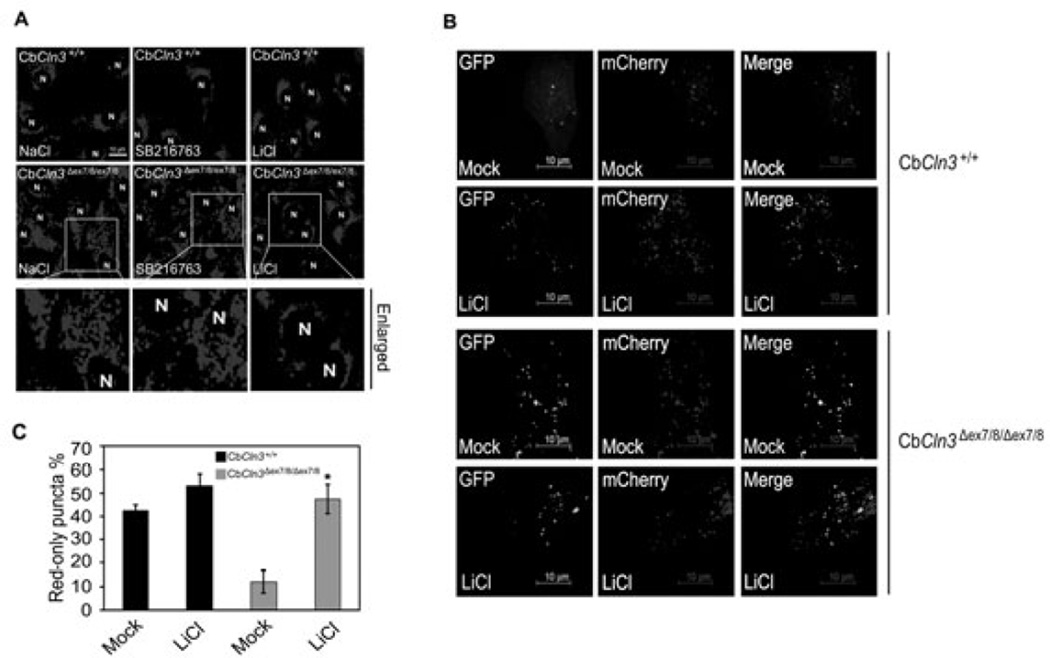

It was reported that autophagosomes and acidic vesicles are translocated into the perinuclear region of cells during autophagy (Jäger et al. 2004). We therefore tested whether lithium affects the subcellular distribution of acidic vesicles, such as lysosomes, in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells. By using Lysotracker, a lysosome marker, we were able to observe that acidic vesicles were widely distributed in the cytosol of CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells under growth conditions, whereas they were enriched near the nuclei of CbCln3+/+ cerebellar cells (Fig. 4A, left). Treatment with lithium, but not SB216763, altered the subcellular distribution of acidic vesicles in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells such that greater numbers of acidic vesicles were found in the perinuclear region (Fig. 4A, right). This distribution pattern is similar to that seen in CbCln3+/+ cells exposed to lithium.

Fig. 4. Lithium promotes perinuclear localization of acidic vesicles and autophagic maturation in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells.

(A) Effect of lithium on the subcellular distribution of lysosomes. CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were treated for 48 h with 10 mM NaCl, 10 µM SB216763 or 10 mM LiCl, incubated with Lysotracker (red), and then examined under a fluorescence microscope. “N” indicates the nucleus. (B and C) Effect of lithium on autophagic maturation. CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were left untreated (Mock) or pretreated with 10 mM LiCl. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with mCherry-GFPLC3 for 48 h in the absence or presence of 10 mM LiCl and then visualized under a confocal microscope (B). The numbers of cells showing only red fluorescence in B were counted as described in Fig. 2B (C).

We used mCherry-GFP-LC3 to further investigate the effect of lithium on the autophagic process in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells. Unlike in wild-type cells (Fig. 4B, upper), the subcellular distributions of GFP-LC3 mostly overlapped with those of mCherry in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Fig. 4B, lower). Treatment with lithium reduced the colocalization of GFP and mCherry in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells (Fig. 4B, lower), which was similar to that in control CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 4B, upper and Fig. 4C). These results suggest that as in SH-SY5Y cells expressing CLN3 Δ1 or Δ2, autophagic maturation is also restored by lithium treatment in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells.

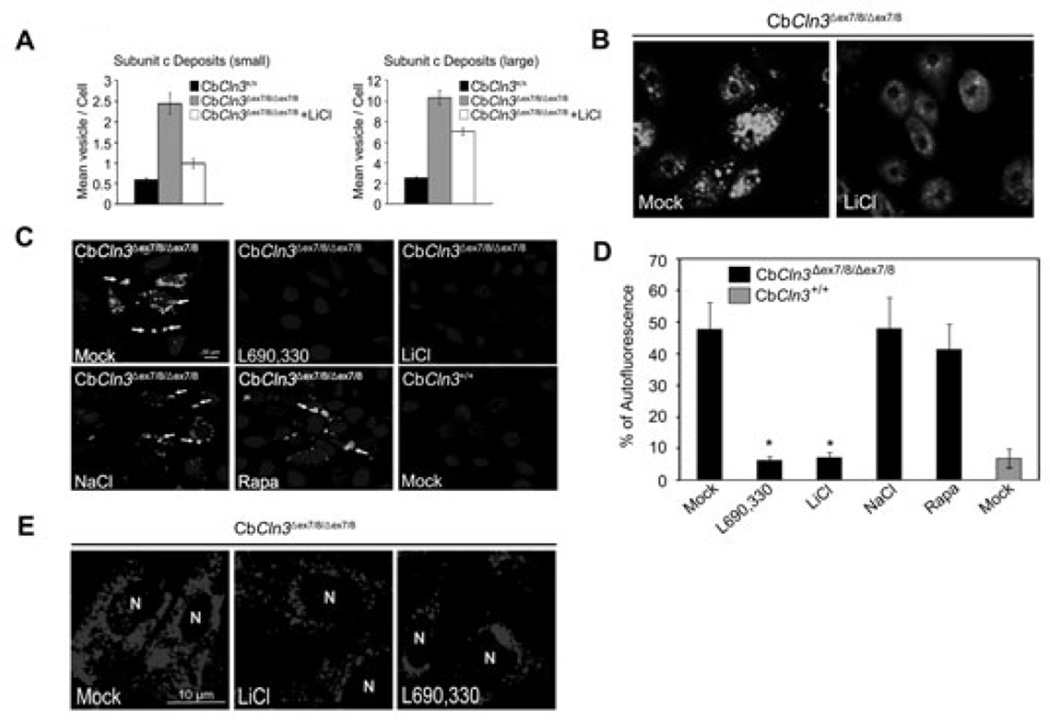

Lithium reduces autofluorescence and accumulation of mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells

Accumulation of autofluorescence enriched with mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c within autophagic vacuoles is a typical feature of JNCL (Cao et al. 2006; Fossale et al. 2004). We therefore examined the clearance of autofluorescence and ATP synthase subunit c in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells following exposure to lithium (Fig. 5). We found that immunoreactivity against mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c was readily detectable in cellular vesicles with punctuated structures and was about 4-to 5-fold higher in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells than in control CbCln3 +/+ cells, (Fig. 5A and B). Notably, treatment with lithium significantly reduced vesicular accumulation of mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c and autofluorescence in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Fig. 5A and B).

Fig. 5. Lithium or an IMPase inhibitor reduces accumulation of mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c and autofluorescence in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells.

(A and B) Effect of lithium on the deposition of mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c. CbCln3+/+ or CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were left untreated or incubated with 10 mM LiCl for 14 days and then immunostained using anti-mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c antibody. The numbers of vesicles per cell (mean vesicle count/cell) were counted under a fluorescence microscope (A) and a typical image is shown (B). (C and D) Effect of lithium on the accumulation of autofluorescence. CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were left untreated (Mock) or incubated with 10 mM NaCl, 100 µM L690,330, 0.2 µM rapamycin (Rapa) or 10 mM LiCl for 7 days. The autofluorescence (arrows) was visualized under a confocal microscope (C). Cells showing autofluorescence were counted and their percentage among total cell numbers are represented as bars (means ± S.D., n > 30). Asterisk indicates significant difference from control (p < 0.05) (D). (E) Effect of L690,330 on the subcellular distribution of lysosomes. CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were left untreated (Mock) or treated with 10 mM LiCl or 100 µM L690,330 for 48 h, incubated with Lysotracker (red) and then examined under a fluorescence microscope. “N” indicates the nucleus.

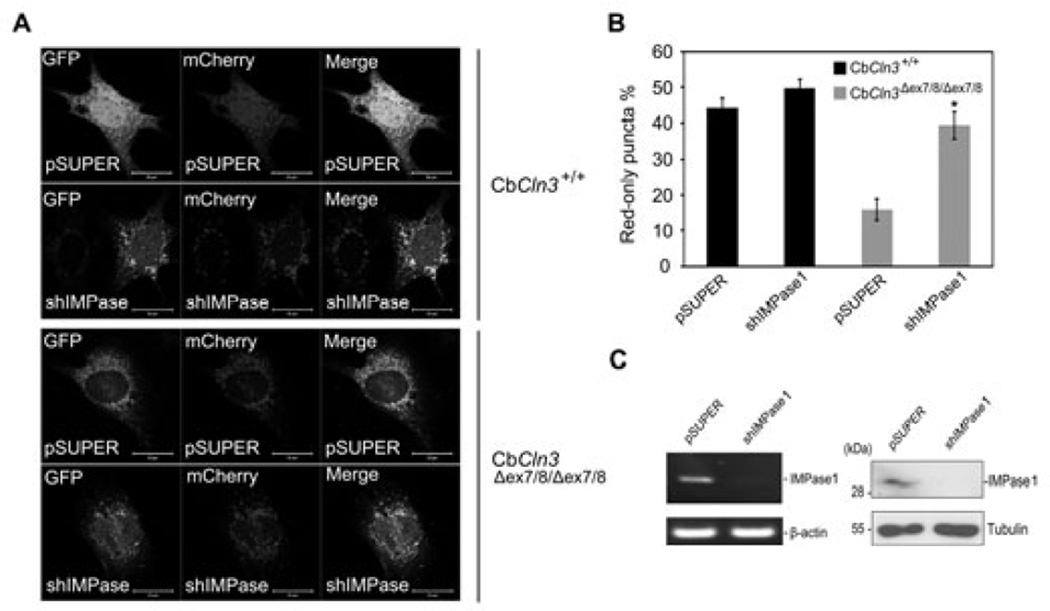

Interestingly, L690,330, an inhibitor of IMPase (Sarkar et al. 2005), very potently reduced the autofluorescence within CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, though rapamycin had no effect (Fig. 5C and D). In addition, L690,330 was as effective as lithium to induce perinuclear localization of acidic vesicles (Fig. 5E). Treatment with L690,330 also reduced the level of LC3-II and number of LC3 dots in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (data not shown). Further, we reduced the expression of IMPase1 using small hairpin RNA (shRNA) in homozygous CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Fig. 6C) and investigated its effect on autophagic maturation. By ectopic expression analysis of mCherry-GFP-LC3, we found that downregulation of IMPase1 expression in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells significantly decreased the colocalization pattern of mCherry and GFP signals and increased the numbers of red-only puncta to a level similar to that in control CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 6A and B). On the contrary, we could not observe these effects in CbCln3+/+ cells. Given that lithium is known to induce autophagy by inhibiting IMPase (Sarkar et al. 2008), these findings suggest that lithium reduces vesicular accumulation of mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, probably through inhibition of IMPase, which in turn restores autophagic maturation.

Fig. 6. Knockdown of IMPase1 increases autophagic maturation in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells.

(A–C) Effect of IMPase knockdown on autophagic maturation in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells. CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells were transiently co-transfected with mCherry-GFP-LC3 and either control shRNA (pSUPER) or IMPase1 shRNA (shIMPase1) for 48 h. Cells were then examined under a confocal microscope (A) and the numbers of cells showing only red fluorescence in A were counted (B). Bars indicate means ± S.D. (n > 20 cells) with significant difference from control (pSUPER) (p < 0.05). Expression level of IMPase1 was examined by quantitative RT-PCR (left) and Western blotting using IMPase1 antibody (right) (C).

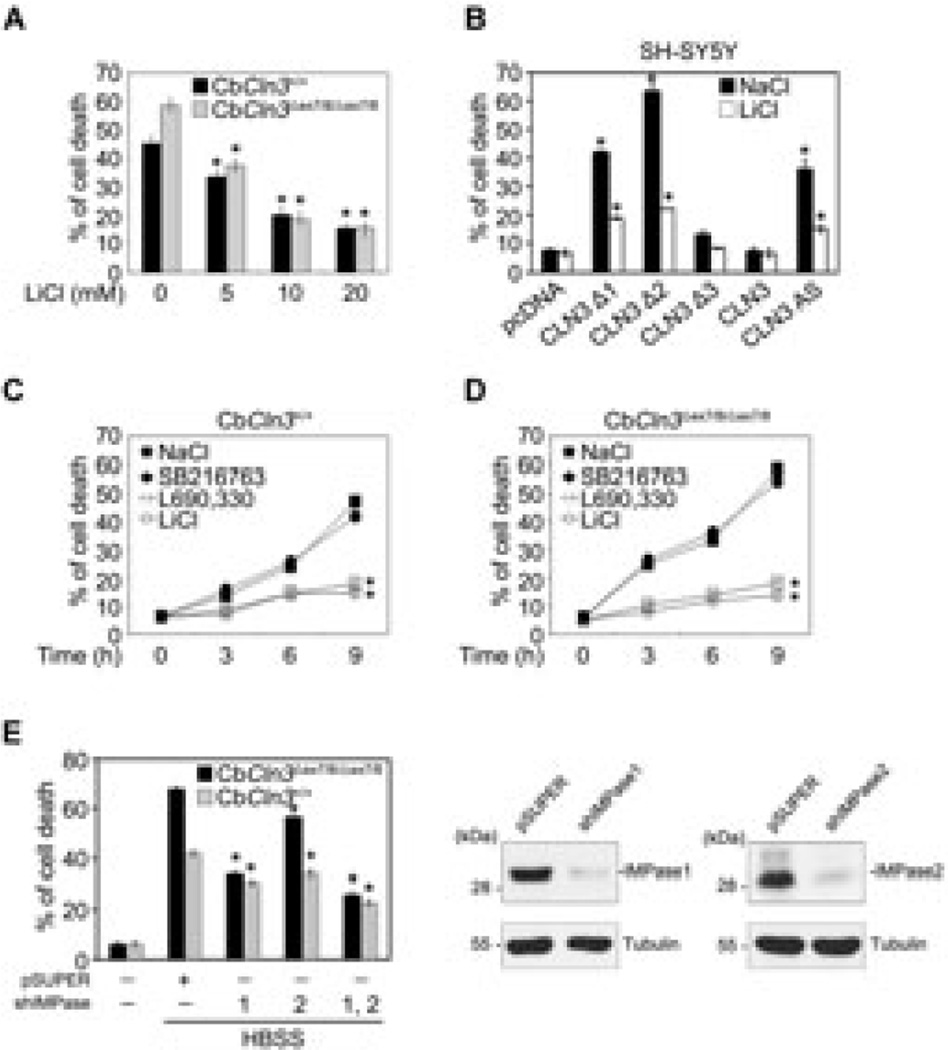

Lithium protects Cln3 mutant cells from starvation-induced cell death

The findings summarized so far led to hypothesize that if lithium rescues impaired autophagy in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells, lithium-treated cells might be more resistant to cell death triggered by autophagic stress than untreated cells. To test that idea, we initially incubated cells in amino acid-free medium, which induced cell death in 45% of CbCln3+/+ cells and 58% of CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells (Fig. 7A), which indicates the latter are more vulnerable to amino acid starvation-induced cell death. Treatment with lithium suppressed cell death in both Cln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells; moreover, the suppression was more pronounced in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells than in CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 7A, C, and D). In addition, cell death induced by ectopic expression of CLN3 Δ1 or Δ2, or CLN3 AS was significantly inhibited by lithium (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7. Lithium reduces the vulnerability of CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells to starvation-induced cell death.

(A) Effect of lithium on the sensitivity of CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells to starvation-induced cell death. CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells were incubated in amino acid-free medium for 12 h in the absence or presence of LiCl, after which the incidences of cell death were determined using a Live/Dead cell assay. Bars indicate means ± S.D. (n > 3). (B) Suppression of CLN3 mutation-induced cell death by lithium. SH-SY5Y cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA, pCLN3Δ1, pCLN3Δ2, pCLN3Δ3, pCLN3 AS or pCLN3, after which cells were treated for 24 h with 10 mM NaCl or 10 mM LiCl. Cell death assays were performed as in (A). (C and D) Suppression of amino aciddeprivation- induced cell death by L390,330 IMPase inhibitor. CbCln3+/+ (C) and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 (D) cerebellar cells were incubated for the indicated times in amino acid-free medium in the absence or presence of 10 mM NaCl, 10 µM SB216763, 10 µM L690,330 or 10 mM LiCl. Cell death assays were performed as in (A) and values indicate means ± S.D. (n = 3). (E) Reducing IMPase expression suppresses amino acid deprivation-induced cell death. CbCln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells were transiently transfected for 48 h with IMPase1 shRNA, IMPase2 shRNA or both, after which they were incubated for 9 h with complete medium or amino acid-free medium (HBSS). Cell death assays were performed as in (A) and values indicate means ± S.D. (n = 3) (left). Expression levels of IMPase1 and IMPase2 were determined by Western blotting using IMPase1 and IMPase2 antibodies (right). Asterisks indicate significant difference from control (p < 0.05).

Like lithium, treatment with L690,330 was effective to inhibit starvation-induced cell death in Cln3+/+ and CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells and the inhibition was more profound in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells than in CbCln3+/+ cells (Fig. 7C and D). Similarly, down-regulation of either IMPase1 or IMPase2 expression using isoform-specific shRNA suppressed amino acid starvation-induced cell death in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells, though IMPase1 knockdown was more potent to suppress cell death than IMPase2 knockdown (Fig. 7E). These results suggest that the vulnerability of CLN3-deficient neuronal cells or those harboring a CLN3 mutant, to autophagic stress is reduced by lithium or L690,330. We therefore propose that lithium may function to rescue autophagic clearance in the CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cell model of JNCL, most likely through IMPase inhibition.

Discussion

Autophagy is generally thought to be a survival function enabling cellular homeostasis to be maintained through degradation of damaged cellular organelles, such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, within autophagosomes (Levine and Yuan, 2005). The autophagosomes then eventually fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes for further degradation. Earlier reports showed that mTOR is downregulated and the trafficking of autophagic vacuoles is impaired in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells and in tissue samples from JNCL patients (Cao et al. 2006). This suggests that the increase in the number of autophagosomes and in the amount of autofluorescence seen in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells and Cln3 knockdown cells results from a defect in the autophagic process, most likely in the fusion of autophagic vacuoles with lysosomes (Cao et al. 2006). Thus, CLN3 appears to function in the trafficking of autophagic vacuoles to the perinuclear region for clearance during autophagy. Moreover, this function is apparently mediated by one or more domains in the C-terminal portion of the protein, as it is lost in cells expressing a CLN3 C-terminal deletion mutant (CLN3 Δ1 or Δ2).

By clearing the accumulated autofluorescence from CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells, lithium should compensate for or overcome the defective process in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells and Cln3 knockdown cells. On the basis of our observations that lithium reduced LC3-II levels and enhanced degradation of GFP-LC3 in mCherry-GFP-LC3 assays, we suggest that lithium compensates for CLN3 defects by modulating downstream mediators of CLN3 signaling, which may increase the fusion of autophagic vacuoles with lysosomes for autophagic maturation, or may activate an alternative pathway to increase autophagy. In either case, lithium likely enhances autophagic clearance in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells via IMPase which is distinct from the induction of autophagy induced by mTOR inhibition. Consistent with those ideas, rapamycin did not enhance the clearance of autofluorescence, suggesting there are at least two ways to induce or increase autophagy, which includes inhibition of mTOR or IMPase activity. In CLN3-deficient cells, IMPase-dependent or mTOR-independent autophagy could serve as an effective means of rescuing the otherwise impaired autophagic process. IMPase modulates cellular levels of IP3, which likely acts via its receptor to regulate autophagy (Vicencio et al. 2009).

During the autophagic process, autophagosomes are formed in the cytosol, after which their subcellular localization shifts to the perinuclear region, along with that of endosomal/lysosomal vesicles (Jäger et al. 2004; Yogalingam and Pendergast, 2008), which suggests autophagic maturation may be regionally restricted. We found that, as reported previously (Fossale et al. 2004), the subcellular distribution of acidic vesicles is more scattered in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells than in wild-type cells; however, treating CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells with lithium, an inhibitor of both GSK-3β and IMPase or IMPase inhibitor, but not with SB216763, another GSK-3β inhibitor, induced a redistribution of acidic vesicles into the perinuclear region. Collectively then, these findings suggest that lithium restores defective trafficking step during the autophagic process in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells and that a pathway to autophagic maturation is preserved and is regulated by IMPase, but not by GSK-3β, in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells.

It has been proposed that lithium directly inhibits IMPase in vivo and in vitro and that it reduces cellular myo-inositol, which in turn inhibits the production of PI-derived second messengers (Berridge et al. 1989; Deranieh and Greenberg, 2009). How this relates to the mechanism by which lithium modulates cell survival is not clearly understood, however. In simple terms, it may be that lithium mitigates the deteriorative effects of mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c accumulation in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells by increasing its clearance via IMPase-mediated autophagy, thereby reversing the autophagic defect and improving cell viability.

Lithium may also reduce aberrant increases in cytosolic calcium levels. We previously showed that CLN3 deletion increased cytosolic calcium in neuronal cells, increasing their vulnerability to cell death (Chang et al. 2007). In addition, calsenilin, a calcium-binding protein exhibiting proapoptotic activity (Jo et al. 2001), was upregulated in Cln3 knockdown cells and in the brains of Cln3 knock-out mice (Chang et al. 2007). Other studies have also shown that increases in intracellular calcium affect autophagy (Høyer-Hansen et al. 2007) and that lithium is able to suppress the rise in intracellular calcium caused by glutamate (Sourial-Bassilious et al. 2009). Thus, lithium may protect CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cells by modulating levels of intracellular calcium.

In summary, although we should further investigate the effect of lithium in mouse model of JNCL, our findings so far suggest that lithium rescues otherwise impaired trafficking of acidic vesicles in CbCln3Δex7/8/Δex7/8 cerebellar cells, perhaps thereby providing a new therapeutic target for the treatment of JNCL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. D. Pearce (University of Rochester, USA) for providing lymphoblastoid cell lines (homozygous 1.02-kb deletion) from JNCL patients and whole brains from Cln3 knock-out mice, Dr. T. Ohnishi (RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Japan) for providing IMPase1 and IMPase2 antibodies and Ms. P. Wolf (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston) for technical assistance. Dr. J. W. Chang was supported by a Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (MOEHRD) [KRF-2007-355-C00032]. This work was supported by grants from CRI-Acceleration Research, Brain Research of the 21C Frontier Research Program and Global Research laboratory funded by the Korea Research Foundation (to Y. K. Jung) and by the Harvard Neurodiscovery Center and the Massachusetts Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, USA (to S. L. Cotman).

References

- Autti T, Raininko R, Vanhanen SL, Santavuori P. MRI of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. I. Cranial MRI of 30 patients with juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:476–482. doi: 10.1007/BF00607283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Downes CP, Hanley MR. Neural and developmental actions of lithium: a unifying hypothesis. Cell. 1989;59:411–419. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busceti CL, Biagioni F, Aronica E, Riozzi B, Storto M, Battaglia G, Giorgi FS, Gradini R, Fornai F, Caricasole A. Induction of the Wnt inhibitor, Dickkopf-1, is associated with neurodegeneration related to temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48:694–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Espinola JA, Fossale E, Massey AC, Cuervo AM, MacDonald ME, Cotman SL. Autophagy is disrupted in a knock-in mouse model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:20483–20493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio I, Calderone A, Busceti CL, et al. Induction of Dickkopf-1, a negative modulator of the Wnt pathway, is required for the development of ischemic neuronal death. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:2647–2657. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5230-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JW, Choi H, Kim HJ, Jo DG, Jeon YJ, Noh JY, Park WJ, Jung YK. Neuronal vulnerability of CLN3 deletion to calcium-induced cytotoxicity is mediated by calsenilin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:317–326. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang DM. The antiapoptotic actions of mood stabilizers: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1053:195–204. doi: 10.1196/annals.1344.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman SL, Vrbanac V, Lebel LA, et al. Cln3 (Deltaex7/8) knock-in mice with the common JNCL mutation exhibit progressive neurologic disease that begins before birth. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:2709–2721. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.22.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Duman RS. Finding the intracellular signaling pathways affected by mood disorder treatments. Neuron. 2003;24:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deranieh RM, Greenberg ML. Cellular consequences of inositol depletion. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009;37:1099–1103. doi: 10.1042/BST0371099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossale E, Wolf P, Espinola JA, et al. Membrane trafficking and mitochondrial abnormalities precede subunit c deposition in a cerebellar cell model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. BMC Neurosci. 2004;10:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-5-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golabek AA, Kida E, Walus M, Kaczmarski W, Michalewski M, Wisniewski KE. CLN3 protein regulates lysosomal pH and alters intracellular processing of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta protein precursor and cathepsin D in human cells. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000;70:203–213. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskell RE, Carr CJ, Pearce DA, Bennett MJ, Davidson BL. Batten disease: evaluation of CLN3 mutations on protein localization and function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;5:735–744. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.5.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiseke A, Aguib Y, Riemer C, Baier M, Schätzl HM. Lithium induces clearance of protease resistant prion protein in prion-infected cells by induction of autophagy. J. Neurochem. 2009;109:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski P, et al. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol. Cell. 2007;25:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger S, Bucci C, Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E, Saftig P, Eskelinen EL. Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:4837–4848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo DG, Kim MJ, Choi YH, Kim IK, Song YH, Woo HN, Chung CW, Jung YK. Pro-apoptotic function of calsenilin/DREAM/KChIP3. FASEB J. 2001;15:589–591. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0541fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Ramirez-Montealegre D, Pearce DA. A role in vacuolar arginine transport for yeast Btn1p and for human CLN3, the protein defective in Batten disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;23:15458–15462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136651100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy. 2007;3:452–460. doi: 10.4161/auto.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Yuan J. Autophagy in cell death: an innocent convict? J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2679–2688. doi: 10.1172/JCI26390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manji HK, Lenox RH. Lithium: a molecular transducer of mood-stabilization in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19:161–166. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 2002;27:421–429. doi: 10.1247/csf.27.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh JY, Lee H, Song S, et al. SCAMP5 links endoplasmic reticulum stress to the accumulation of expanded polyglutamine protein aggregates via endocytosis inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:11318–11325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807620200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi T, Ohba H, Seo KC, Im J, Sato Y, Iwayama Y, Furuichi T, Chung SK, Yoshikawa T. Spatial expression patterns and biochemical properties distinguish a second myo-inositol monophosphatase IMPA2 from IMPA1. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:637–646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604474200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce DA, Ferea T, Nosel SA, Das B, Sherman F. Action of BTN1, the yeast orthologue of the gene mutated in Batten disease. Nat. Genet. 1999a;22:55–58. doi: 10.1038/8861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce DA, Nosel SA, Sherman F. Studies of pH regulation by Btn1p, the yeast homolog of human Cln3p. Mol. Genet. Metab. 1999b;66:320–323. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persaud-Sawin DA, Boustany RM. Cell death pathways in juvenile Batten disease. Apoptosis. 2005;10:973–985. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-0733-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phiel CJ, Wilson CA, Lee VM, Klein PS. GSK-3alpha regulates production of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta peptides. Nature. 2003;423:435–439. doi: 10.1038/nature01640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Montealegre D, Pearce DA. Defective lysosomal arginine transport in juvenile Batten disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:3759–3773. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein DC. The roles of intracellular protein-degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:780–786. doi: 10.1038/nature05291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santavuori P. Neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses in childhood. Brain Dev. 1988;10:80–83. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(88)80075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Floto RA, Berger Z, Imarisio S, Cordenier A, Pasco M, Cook LJ, Rubinsztein DC. Lithium induces autophagy by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170:1101–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Krishna G, Imarisio S, Saiki S, O'Kane CJ, Rubinsztein DC. A rational mechanism for combination treatment of Huntington's disease using lithium and rapamycin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:170–178. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourial-Bassillious N, Rydelius PA, Aperia A, Aizman O. Glutamate-mediated calcium signaling: a potential target for lithium action. Neuroscience. 2009;161:1126–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusi-Rauva K, Luiro K, Tanhuanpää K, Kopra O, Martín-Vasallo P, Kyttälä A, Jalanko A. Novel interactions of CLN3 protein link Batten disease to dysregulation of fodrin-Na+, K+ ATPase complex. Exp. Cell Res. 2008;314:2895–2905. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicencio JM, Ortiz C, Criollo A, et al. The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor regulates autophagy through its interaction with Beclin 1. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1006–1017. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer JM, Benedict JW, Getty AL, Pontikis CC, Lim MJ, Cooper JD, Pearce DA. Cerebellar defects in a mouse model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Brain Res. 2009;1266:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogalingam G, Pendergast AM. Abl kinases regulate autophagy by promoting the trafficking and function of lysosomal components. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:35941–35953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804543200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.