Abstract

Here we report a summary classification and the features of five anaerobic oral bacteria from the family Peptostreptococcaceae. Bacterial strains were isolated from human subgingival plaque. Strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 represent the first known cultivable members of “yet uncultured” human oral taxon 081; strain AS15 belongs to “cultivable” human oral taxon 377. Based on 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons, strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 are distantly related to Eubacteriumyurii subs. yurii and Filifactor alocis, with 93.2 – 94.4 % and 85.5 % of sequence identity, respectively. The genomes of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8 and AS15 are 2,541,543; 2,312,592; 2,594,242; 2,553,276; and 2,654,638 bp long. The genomes are comprised of 2277, 1973, 2325, 2277, and 2308 protein-coding genes and 54, 57, 54, 36, and 28 RNA genes, respectively. Based on the distinct characteristics presented here, we suggest that strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 represent a novel genus and species within the family Peptostreptococcaceae, for which we propose the name Peptoanaerobacter stomatis gen. nov., sp. nov. The type strain is strain ACC19aT (=HM-483T; =DSM 28705T; =ATCC BAA-2665T).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40793-015-0027-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Peptostreptococcaceae, Peptoanaerobacter stomatis, Uncultivable bacteria, Anaerobic oral bacteria, Human oral taxa

Introduction

The oral cavity is a major gateway to the human body [1] and one of the principle sites of interest to the Human Microbiome Project, which aims to characterize this microbiome and understand its role in health and disease.

The 16S rRNA surveys and metagenomic analyses indicate that the typical oral community is comprised of over 700 bacterial species [2–4], approximately half of which have been isolated in culture and formally named. The rest remain uncultivated or unclassified [1, 5]. Anaerobic species are of particular importance as they constitute approximately one half of the human oral microbiome [6–8] and likely play an important role in the function of the oral microbial community.

The Human Oral Microbiome Database, provides comprehensive information on currently known prokaryote species and presents a provisional “oral taxa” naming scheme for the presently unnamed cultivable and uncultivable species. HOMD also provides links to genome sequencing projects of oral bacteria [9]. There are annotated genomes for 381 oral taxa currently available at HOMD.

Five anaerobic strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, and AS15 from the family Peptostreptococcaceae were isolated earlier from the subgingival plaque obtained from two young African American and two young Caucasian females. Cultivation techniques were described before [10].

Family Peptostreptococcaceae currently is represented by five validly-named genera, Anaerosphaera,Filifactor,Peptostreptococcus,Sporacetigenium, and Tepidibacter [11, 12], and several unclassified species. At this time, genome sequences of oral bacteria from the family Peptostreptococcaceae are available for three strains of Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, one strain of P. stomatis, one strain of Filifactor alocis, and one strain of unclassified Eubacteriumyurii subsp. margaretiae.

According to HOMD, the genera Peptostreptococcus and Filifactor are represented by three oral taxa, while the other eleven Peptostreptococcaceae oral taxa remain formally unclassified. To date, only two unclassified oral taxa are represented by cultivable isolates, whereas nine stay “yet uncultured” and are known only by their molecular signatures. Strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 described here represent the first known cultivable members of “yet uncultured” human oral taxon 081; strain AS15 is classified as a member of “cultivable” oral taxon 377.

Here we report a summary classification and the features of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, and AS15 together with their genome sequence and annotation. Strains have been deposited in BEI Resources, ATCC and DSMZ under deposition numbers HM-483, DSM 28705, ATCC BAA-2665 (for ACC19a), HM-484, DSM 28703, ATCC BAA-2664 (for CM2), HM-485, DSM 28704 (for CM5), HM-765, DSM 28706 (for OBRC8), and HM-766, DSM 28702, ATCC BAA-2661 (for AS15) respectively.

Organism information

Classification and features

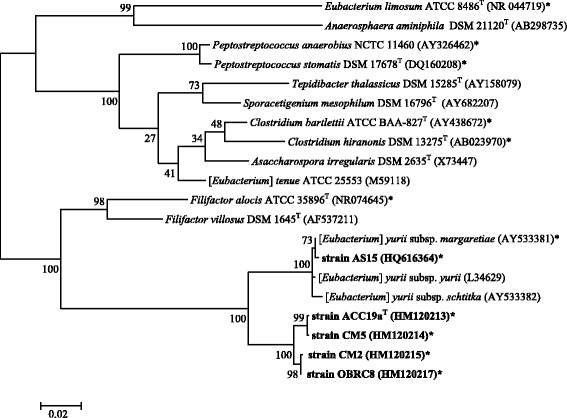

Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons showed that strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 were only distantly related to Eubacteriumyurii subs. yurii, E.yurii subs. schtitka,E.yurii subsp. margaretiae and Filifactor alocis, and formed a separate branch within the Peptostreptococcaceae, while strain AS15 was closely related E.yurii subsp. margaretiae (Fig. 1). The validly published species of E.yurii subs. yurii, E.yurii subs. schtitka and [E.] yurii subs. margaretiae have historically been misclassified and were included within the genus Eubacterium [13, 14], but according to 16S rRNA gene sequence phylogeny, [E.] yurii falls into the Peptostreptococcaceae [15].

Fig. 1.

Maximum-Likelihood phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, and AS15 (shown in bold) together with other representatives of the Peptostreptococcaceae family and other related human bacteria. The tree was derived based on Tamura-Nei model using MEGA 5 [39]. Bootstrap values > 50 % calculated for 1000 subsets are shown at branch-points. Bar 0.02 substitutions per position. Strains whose genomes have been sequenced are marked with an asterisk

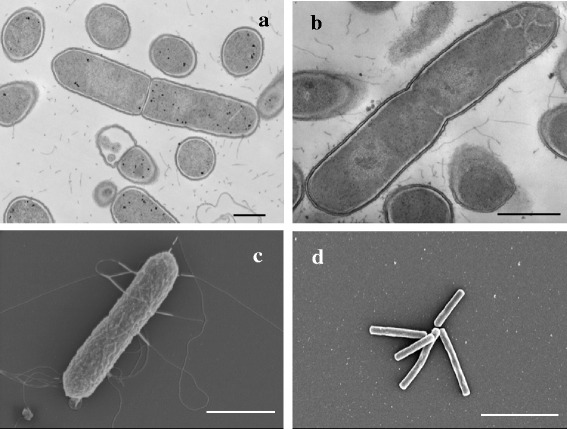

Cells of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 are non-spore-forming, highly motile, peritrichous rods with round ends; cells often form chains. Cells of strain AS15 are motile, monotrichous, straight rods with square ends that often form rosettes or brush-like aggregates (Table 1, Fig. 2). On liquid TY medium, cells of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 range from 1.0 to 3.4 μm in length and from 0.4 to 0.8 μm in width; cells of strain AS15 are 1.5 – 4.7 μm long and 0.4 - 0.5 μm wide (Table 1, Fig. 2). Cells are Gram-positive, structurally and by staining (Table 1, Fig. 2). After 48-72 h incubation on TY blood agar plates at 37 °C, strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 formed pin-point, beige, circular, convex, non-hemolytic colonies, approximately 0.5 mm in diameter. Colonies of strain AS15 are circular, umbonate, alpha-hemolytic, yellow-greenish in pigment, 1 mm in diameter after 48-72 h, and 2-3 mm in diameter after 168 h.

Table 1.

Classification and general features of the five oral isolates according to the MIGS recommendation [34]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strain ACC19a | strain CM2 | strain CM5 | strain OBRC8 | strain AS15 | |||

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | Domain Bacteria | Domain Bacteria | Domain Bacteria | Domain Bacteria | TAS [35] | |

| Phylum Firmicutes | Phylum Firmicutes | Phylum Firmicutes | Phylum Firmicutes | Phylum Firmicutes | TAS [36] | ||

| Class Clostridia | Class Clostridia | Class Clostridia | Class Clostridia | Class Clostridia | TAS [36] | ||

| Order Clostridiales | Order Clostridiales | Order Clostridiales | Order Clostridiales | Order Clostridiales | TAS [36] | ||

| Family Peptostreptococcaceae | Family Peptostreptococcaceae | Family Peptostreptococcaceae | Family Peptostreptococcaceae | Family Peptostreptococcaceae | IDA | ||

| Genus Peptoanaerobacter | Genus Peptoanaerobacter | Genus Peptoanaerobacter | Genus Peptoanaerobacter | Genus Eubacterium | IDA | ||

| Species Peptoanaerobacter stomatis | Species Peptoanaerobacter stomatis | Species Peptoanaerobacter stomatis | Species Peptoanaerobacter stomatis | Species Eubacterium yurii subspecies margaretiae | IDA | ||

| Type strain HM-483; DSM 28705; ATCC BAA-2665 | TAS [10] | ||||||

| Gram stain | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rods with round ends | Rods with round ends | Rods with round ends | Rods with round ends | Rods with square ends, forms rosettes | IDA | |

| Cell size, μm | 0.4-0.8 × 1.2-2.5 | 0.5-0.7 × 1.0-2.3 | 0.5-0.7 × 1.3-2.8 | 0.6-0.8 × 1.4-3.5 | 0.4-0.5 × 1.5-4.7 | IDA | |

| Motility/Flagella | +/peritrichous | +/peritrichous | +/ peritrichous | +/ peritrichous | +/single subpolar | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Does not form spores | Does not form spores | Does not form spores | Does not form spores | Does not form spores | IDA | |

| Temperature range | 30 – 42 oC | 30 – 42 oC | 30 – 42 oC | 30 – 42 oC | 30 – 42 oC | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 37 °C | 37 °C | 37 °C | 37 °C | 37 °C | IDA | |

| pH range; Optimum | 6.5-7.5; 7 | 6.5-7.5; 7 | 6.5-7.5; 7 | 6.5-7.5; 7 | 6.5-7.5; 7 | IDA | |

| Carbon source | Yeast extract | Yeast extract, Glucose, Sucrose, Maltose | Yeast extract | Yeast extract, Glucose, Sucrose, Maltose | Yeast extract, Glucose, Sucrose, Maltose | IDA | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Human oral cavity | TAS [10] | ||||

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Normal | IDA | ||||

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Strictly anaerobic | TAS [10] | ||||

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living | TAS [10] | ||||

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non pathogen | TAS [10] | ||||

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Boston, Massachusetts, USA | TAS [10] | ||||

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | March 1, 2010 | TAS [10] | ||||

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 42.34 | NAS | ||||

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | −71.09 | NAS | ||||

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 5.8 m above see level | NAS | ||||

aEvidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from Gene Ontology project [37, 38]

Fig. 2.

Transmission and scanning electron micrographs of anaerobic oral bacteria from the family Peptostreptococcaceae. General morphology and Gram-positive cell wall structure of strains CM5 (a) and ACC19a (b), peritrichous flagella of strain CM2 (c), rosettes or brush-like structures formed by strain AS15 (d). Bars, 500 nm (a, b), 1 μm (c) and 5 μm (d)

Isolated strains grew only under strict anaerobic conditions. Growth occurred from 30 to 42 °C, with optimum growth at 37 °C. All isolates were susceptible to discs containing 1 mg kanamycin, 2 units penicillin, 60 μg erythromycin, 30 μg chloramphenicol, 30 μg tetracycline and bile. Catalase, oxidase and urease activities were negative; nitrate reduction was not detected, gelatin was not liquefied, and aesculin was not hydrolyzed. Strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 did not produce indole, while strain AS15 did produce indole (Table 1). All strains were able to grow on 2.0 – 10 g l−1 of yeast extract, but not on casamino acids. No visible biomass was formed in medium with 0.5 – 2.0 g l−1 of yeast extract only. All five strains produced acid on API 20A media containing glucose, maltose and sucrose, but not lactose, arabinose, cellobiose, mannose, melezitose, raffinose, rhamnose, trehalose, xylose, glycerol, mannitol, salicin and sorbitol. All produced gas on TY liquid medium. In liquid medium, supplemented with 5.0 g l−1 of yeast extract, strains CM2, OBRC8 and AS15 fermented D-glucose, D-sucrose and D-maltose; strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5 and OBRC8 poorly fermented L-glutamine; strain CM2 fermented L-serine; strains ACC19a, CM5, and AS15 weakly fermented L-alanine; strains CM2, CM5, and AS15 poorly fermented L-valine. The major metabolic end products of strains ACC19a, CM2, and CM5 on TY medium were acetate and propionate (Table 1).

Cell biomass that was grown in TY liquid medium for 48 h was used for the whole-cell fatty acids analysis. Fatty acids were methylated, extracted, and analyzed by GC using the Sherlock Microbial Identification System at Microbial ID, Inc. Fatty acid methyl esters profile showed that strain ACC19a contained C12:0 (5.6 %), C14:0 (46.6 %), C16:0 (7.8 %), C16:1ω7c (9.4 %), and C16:1ω7c DMA (5.2 %) as major fatty acids; strain CM2 contained C 12:0 (5.2 %), C14:0 (47.1 %), C16:0 (5.7 %), C16:1ω7c (6.9 %), and C16:1ω7c DMA (7.2 %); and strain CM5 contained C14:0 (40.6 %), C16:0 (7.4 %), C16:1ω7c (11.5 %), and C16:1ω7c DMA (6.8 %) (Table 1). Genomic DNA G + C content of strains ACC19a, CM5, CM2 and OBRC8 was between 30.0 – 30.7 %, and of strain AS15 was 32.2 % (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genomes statistics

| Attribute | strain ACC19a | strain CM2 | strain CM5 | strain OBRC8 | strain AS15 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | %a | Value | %a | Value | %a | Value | %a | Value | %a | |

| Genome size (bp) | 254, 1543 | 100 | 231, 259, 2 | 100 | 259, 424, 2 | 100 | 255, 327, 6 | 100 | 265, 463, 8 | 100 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 215, 2064 | 85 | 196, 164, 0 | 85 | 219, 838, 6 | 85 | 217, 178, 3 | 85 | 220, 441, 4 | 83 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 771, 857 | 30 | 695, 842 | 30 | 790, 067 | 30 | 783, 396 | 31 | 855, 775 | 32 |

| DNA scaffolds | 59 | 100 | 19 | 100 | 106 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 52 | 100 |

| Total genes | 2, 331 | 100 | 2, 030 | 100 | 2, 379 | 100 | 2, 313 | 100 | 2, 336 | 100 |

| Protein coding genes | 2, 277 | 98 | 1, 973 | 97 | 2, 325 | 98 | 2, 277 | 98 | 2, 308 | 99 |

| RNA genes | 54 | 2 | 57 | 3 | 54 | 2 | 36 | 2 | 28 | 1 |

| Pseudo genes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Genes in internal clusters | 21 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 18 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Genes with function prediction | 1, 811 | 78 | 1, 618 | 80 | 1, 873 | 79 | 1, 868 | 81 | 1, 915 | 82 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1, 404 | 60 | 1, 362 | 67 | 1, 448 | 61 | 1, 422 | 61 | 1, 472 | 63 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 1, 856 | 80 | 1, 636 | 81 | 1, 917 | 81 | 1, 822 | 79 | 1, 851 | 79 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 129 | 6 | 120 | 6 | 130 | 6 | 131 | 6 | 174 | 7 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 531 | 23 | 455 | 22 | 505 | 21 | 514 | 22 | 616 | 26 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

a% - Percent of total. The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The genomes were selected for sequencing in 2010-11 by the HMP. For strains ACC19a, CM2, and CM5, sequencing, finishing, and annotation were performed by the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. For strains OBRC8 and AS15, sequencing, finishing, and annotation were performed by the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI). The genomes were deposited in the Genome On-Line Database [16]; the complete genome sequences were deposited in GenBank and are available in the RefSeq database [17–19]. Project information and association with MIGS version 2.0 is presented in Table 3. The genome finishing quality for all strains was High-Quality Draft.

Table 3.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strain ACC19a | strain CM2 | strain CM5 | strain OBRC8 | strain AS15 | ||

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | High-Quality Draft Genome Sequence | ||||

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Two 454 pyrosequencing libraries, one standard 0.6 kb fragment library and one 2.5 kb jump library | Two Illumina libraries, one standard 180 bp fragment library and one 3-5 kb jump library | Two 454 pyrosequencing libraries, one standard 0.6 kb fragment library and one 2.5 kb jump library | Standard Illumina paired-end library | Standard Illumina paired-end library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | 454 FLX Titanium | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 454 FLX Titanium | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | Illumina HiSeq 2000 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 40× | 282× | 39× | 32× | 31× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler v.2.3 | ALLPATHS v. R39099 | Newbler v.2.3 | Celera Assembler v.6.1 | Celera Assembler v.6.1 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | PRODIGAL | PRODIGAL | PRODIGAL | GLIMMER | GLIMMER |

| Locus Tag | HMPREF9629 | HMPREF9630 | HMPREF9628 | HMPREF1143 | HMPREF1142 | |

| GenBank ID | AFZE00000000 | AFZF00000000 | AFZG00000000 | ALNK00000000 | ALJM00000000 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | Dec 19, 2011 | Dec 14, 2011 | Dec 19, 2011 | Aug 27, 2012 | Aug 13, 2012 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi06852 | Gi06853 | Gi06851 | Gi09663 | Gi09662 | |

| BIOPROJECT | 49887 | 49889 | 49891 | 78565 | 78563 | |

| MIGS 13 | Source Material Identifier | HM-483; DSM 28705; ATCC BAA-2665 | HM-484; DSM 28703; ATCC BAA-2664 | HM-485; DSM 28704 | HM-765; DSM 28706 | HM-766; DSM 28702; ATCC BAA-2661 |

| Project relevance | Human Microbiome Project | |||||

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

Strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, and AS15 were cultivated on liquid TY anaerobic medium as previously described [10].

Genomic DNA was extracted from microbial biomass with the PowerMicrobial® Maxi DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc.) using phenol: chloroform in combination with bead beating cell lysis.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Strains ACC19a, CM2, and CM5 were sequenced using two 454 pyrosequence libraries on the 454 platform: one standard 0.6 kb fragment library and one 2.5 kb jump library [20]. Library construction and sequencing process details are available at www.broadinstitute.org and 454 technologies. For strain CM2, additional sequence data was generated using two Illumina libraries on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform: one standard 180 bp fragment library and one 3-5 kb jump library. Library construction and sequencing process details are available at www.broadinstitute.org. Strains ACC19a and CM5 454 data set was assembled using Newbler Assembler version 2.3 PostRelease-11/19/2009 and CM2 data sets were assembled using ALL-PATHS version R39099 (Table 3).

All three assemblies are considered High-Quality Draft and consist of: 59 contigs with a total size of 2,541,543 bases for strain ACC19a; 106 contigs with a total size of 2,594,242 bases for strain CM5; and 19 contigs with a total size of 2,312,592 bases for strain CM2. The error rates of the draft genome sequences for strains ACC19a and CM5 are estimated to be less than one in 10,000 (accuracy of ~ Q40) and less than 1 in 1,000,000 (accuracy of ~ Q60) for strain CM2. Average sequence coverage for strains ACC19a and CM5 is 40× and 39×, respectively, and 282× for strain CM2 (Tables 3, 4 and 2, Additional file 1: Table S1).

Table 4.

Summary of the genomes: one chromosome each and no plasmids

| Strain | Label | Size | Topology | INSDC identifier | RefSeq ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC19a | Chromosome | 2.54 | circular | AFZE00000000.1 | NZ_AFZE00000000.1 |

| CM2 | Chromosome | 2.31 | circular | AFZF00000000.2 | NZ_AFZF00000000.2 |

| CM5 | Chromosome | 2.59 | circular | AFZG00000000.1 | NZ_AFZG00000000.1 |

| OBRC8 | Chromosome | 2.55 | circular | ALNK00000000.1 | NZ_ALNK00000000.1 |

| AS15 | Chromosome | 2.65 | circular | ALJM00000000.1 | NZ_ALJM00000000.1 |

Strains OBRC8 and AS15 were sequenced using Illumina paired-end sequencing technology on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform: one standard Illumina paired-end library. Library construction and sequencing process details are available at www.jcvi.org. Strains OBRC8 and AS15 Illumina data sets were assembled using Celera Assembler version 6.1.

Both assemblies are considered High-Quality Draft and consist of: 40 contigs with a total size of 2,553,276 bases for strain OBRC8 and 52 contigs with a total size of 2,654,638 bases for strain AS15. The error rates of the draft genome sequences for strains OBRC8 and AS15 are estimated to be less than 0.03 or 3 %. Average sequence coverage for strains OBRC8 and AS15 is 32× and 31×, respectively (Tables 3, 4 and 2, Additional file 1: Table S1).

Assessment of coverage, GC content, contig BLAST and 16S rRNA gene classification was consistent with the expected organism for all five genomes.

Genome annotation

Strains ACC19a, CM2, and CM5 were annotated using PRODIGAL [21] with no additional manual curation performed. For strains OBRC8 and AS15, genes were identified using GLIMMER, also with no additional manual curation. Table 2 summarizes statistics for each genome, including gene count, according to the original annotations and the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) and Metagenomes website as of May 15, 2014 [22]. Additional annotations using RAST were performed for comparison [23].

Genome properties

Strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, and AS15 genomes include one circular chromosome of 2,541,543; 2,312,592; 2,594,242; 2,553,276; and 2,654,638 bp, respectively, with DNA G + C content of 30.0 – 32.2 % (Table 4 and 2). The genomes comprise 2277, 1973, 2325, 2277, and 2308 protein-coding genes, respectively, and 54, 57, 54, 36, and 28 RNA genes, respectively. The coding regions accounted for 83.0 – 85.1 % of the genomes for all isolates (Table 2). The total number of genes ranged between 2030 and 2379 and the percent of genes assigned to clusters of orthologous groups (COGs) ranged from 60.2 % - 67.1 % (Table 2). The isolate with the smallest genome size, strain CM2, had the least number of predicted total genes and protein-coding genes, but the highest percentage of genes assigned to COGs. The percentage of genes with signal peptides for strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 ranged between 5.5 – 5.9 %; for strain AS15 the percentage was 7.45 %. The percentage of genes with transmembrane helices for strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 ranged between 21.2 – 22.8 %; for strain AS15 the percentage was 26.4 % (Table 2).

COG values for the annotation data directly from the sequencing centers were found on the IMG website, as of May 15, 2014 (Table 5). The percentages in Table 5 are the number of COG proteins out of the total number of annotated genes. For all strains, 32.9 % - 39.8 % of the proteins were not predicted to be part of a COG category; strain ACC19a had the highest percentage of proteins unassigned (Table 5). Strain CM2 had the highest sequence coverage, at 282×, and the lowest percentage of unassigned proteins, at 32.9 % (Table 3 and 5).

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with general COG functional categories obtained from BROAD or JCVI pipelines

| Code | Description | strain ACC19a | strain CM2 | strain CM5 | strain OBRC8 | strain AS15 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | %a | Value | %a | Value | %a | Value | %a | Value | %a | ||

| J | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis | 136 | 5.8 | 132 | 6.5 | 136 | 5.7 | 136 | 5.9 | 142 | 6.1 |

| A | RNA processing and modification | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| K | Transcription | 105 | 4.5 | 97 | 4.8 | 105 | 4.4 | 106 | 4.6 | 105 | 4.5 |

| L | Replication, recombination and repair | 111 | 4.8 | 96 | 4.7 | 145 | 6.1 | 113 | 4.9 | 104 | 4.5 |

| B | Chromatin structure and dynamics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| D | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning | 23 | 1 | 22 | 1.1 | 23 | 1 | 22 | 1 | 21 | 0.9 |

| V | Defense mechanisms | 46 | 2 | 34 | 1.7 | 42 | 1.8 | 41 | 1.8 | 55 | 2.4 |

| T | Signal transduction mechanisms | 77 | 3.3 | 75 | 3.7 | 78 | 3.3 | 80 | 3.5 | 77 | 3.3 |

| M | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | 70 | 3 | 67 | 3.3 | 69 | 2.9 | 73 | 3.2 | 71 | 3 |

| N | Cell motility | 56 | 2.4 | 50 | 2.5 | 52 | 2.2 | 48 | 2.1 | 55 | 2.4 |

| U | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport | 40 | 1.7 | 33 | 1.6 | 35 | 1.5 | 37 | 1.6 | 41 | 1.8 |

| O | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | 52 | 2.2 | 54 | 2.7 | 52 | 2.2 | 55 | 2.4 | 60 | 2.6 |

| C | Energy production and conversion | 96 | 4.1 | 95 | 4.7 | 98 | 4.1 | 97 | 4.2 | 103 | 4.4 |

| G | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | 75 | 3.2 | 76 | 3.7 | 75 | 3.2 | 75 | 3.2 | 76 | 3.3 |

| E | Amino acid transport and metabolism | 138 | 5.9 | 147 | 7.2 | 142 | 6 | 146 | 6.3 | 146 | 6.3 |

| F | Nucleotide transport and metabolism | 54 | 2.3 | 54 | 2.7 | 54 | 2.3 | 55 | 2.4 | 54 | 2.3 |

| H | Coenzyme transport and metabolism | 69 | 3 | 67 | 3.3 | 69 | 2.9 | 72 | 3.1 | 79 | 3.4 |

| I | Lipid transport and metabolism | 40 | 1.7 | 39 | 1.9 | 41 | 1.7 | 41 | 1.8 | 38 | 1.6 |

| P | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | 77 | 3.3 | 76 | 3.7 | 72 | 3 | 81 | 3.5 | 87 | 3.7 |

| Q | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | 17 | 0.7 | 16 | 0.8 | 16 | 0.7 | 15 | 0.6 | 17 | 0.7 |

| R | General function prediction only | 155 | 6.6 | 171 | 8.4 | 167 | 7 | 170 | 7.3 | 166 | 7.1 |

| S | Function unknown | 125 | 5.4 | 118 | 5.8 | 131 | 5.5 | 120 | 5.2 | 128 | 5.5 |

| - | Not in COGs | 927 | 40 | 668 | 33 | 931 | 39 | 891 | 39 | 864 | 37 |

a% - Percent of annotated genes. The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the genome

Insights from the genome sequences

Metabolic network analysis

The metabolic Pathway/Genome Databases (PGDBs) for strains ACC19a, CM2, and CM5 were generated on February 10, 2013 from genomic data obtained from RefSeq [17–19] by the PathoLogic program using Pathway Tools software version 17.0 [24] and MetaCyc version 17.0 [25]. These PGDBs are categorized as Tier 3, meaning that they were generated computationally, have undergone no subsequent manual curation, and may contain errors [26]. In addition, the RAST annotations of the genomic data for all five strains were uploaded to a downloadable version of Pathway Tools version 17.5 [24].

According to the RAST annotations, for strains ACC19a, CM2, and CM5, complete “sucrose degradation III (sucrose invertase)” pathways were predicted in Pathway Tools, but were marked as not present based on the RefSeq data. Based on the RAST annotations, for strains OBRC8 and AS15, this pathway was also predicted in Pathway Tools. Based on biological testing, strains CM2, OBRC8, and AS15, but not ACC19a and CM5, used sucrose as a carbon source. Strains CM2, OBRC8, and AS15 were also able to use glucose and maltose as carbon sources (Table 1). In Pathway Tools, glucose is part of multiple pathways, including glycolysis I and III, glucose and xylose degradation, and heterolactic fermentation pathways. For all five strains, there was a complete glycolysis III pathway. In Pathway Tools, maltose is also part of multiple pathways, including, the starch degradation I through V and the glycogen degradation I pathways. In the starch degradation V pathway, a 4-α-glucanotransferase (EC 2.4.1.25) is required to degrade maltose into α-D-glucose. We confirmed that strains CM2, OBRC8, and AS15 have a gene for this protein.

Phenotypic and phylogenetic comparison

Based on 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons, strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 are closely related to each other, with 98.9 – 99.9 % sequence identity. These four novel isolates are only distantly related to [Eubacterium] yurii subs. yurii and [E.] yurii subs. schtitka, with 93.2 – 94.4 % 16S rRNA gene sequence identity, and to Filifactor alocis, with 85.5 % sequence identity (Figure 1). Strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 are sharing only 93.6 – 94.0 % of 16S rRNA gene sequence identity with strain AS15, which is below a ‘lower cut-off window’ of 95 % for the new genus differentiation [27, 28]. Predicted DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) values [29–31] between each of the novel strains, ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 and strain AS15 together with [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae vary between 13.8 % - 14.3 %, clearly indicating two separate taxa (Table 6).

Table 6.

Predicted values of DNA-DNA hybridizationa between strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, AS15 and related members of the family Peptostreptococcaceae

| Predicted value of DDH, % | Accession | strain ACC19a | stain CM2 | strain CM5 | strain OBRC8 | strain AS15 | [Eubacterium] yurii subsp. margaretiae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strain ACC19a | AFZE00000000 | ||||||

| strain CM2 | AFZF00000000 | 67.6 | |||||

| strain CM5 | AFZG00000000 | 84.5 | 68.7 | ||||

| strain OBRC8 | ALNK00000000 | 72 | 78.3 | 68.8 | |||

| strain AS15 | ALJM00000000 | 14.2 | 13.8 | 14.3 | 14.3 | ||

| [Eubacterium] yurii subsp. margaretiae | AEES00000000 | 13.9 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.2 | 91 | |

| Filifactor alocis | CP002390 | 14 | 13.1 | 13.8 | 13.9 | 13.2 | 13.1 |

Predicted DDH value between four strains, ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 varies between 67.6 and 84.5 % (Table 6), which is above or on the brink of the threshold of 70 %, the widely accepted value of relatedness used for species demarcation [28, 32, 27]. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) value between four strains varies from 95.51 to 98.31 %, which is above 95 %, the value of relatedness recommended for species delineation [33]. Both, DDH and ANI values suggest that four strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 belong to the same species.

Strain AS15 is closely related to [E.] yurii subs. yurii, [E.] yurii subs. schtitka and [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae with 98.8 - 99.3 % sequence identity. The predicted DDH value of 91.0 % between strains AS15 and [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae together with 16S rRNA gene sequence identity values indicates that strains AS15, [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae, [E.] yurii subs. yurii and [E.] yurii subs. schtitka represented the same species (Fig. 1, Table 6).

The number of genes identified by RAST [23] in biosynthetic pathway of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, AS15 and related organisms is shown in Table 7. Eight to nine genes associated with synthesis of teichoic and lipoteichoic acids, as annotated by RAST, were found in the genomes of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8; nine to eleven were found in the genomes of AS15 and [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae; and four were found in the genome of F. alocis (Table 7). We detected one gene associated with synthesis of benzoquinones or naphthoquinones in genomes of strain AS15, [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae only. There were no predicted gene sequences with recognizable homology to mycolic acids or lipopolysaccharides biosynthesis. Three and six RAST-annotated genes associated with diaminopimelic acid (DAP) synthesis were present in the genome of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, and AS15 and [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae, respectively. According to the RAST annotations, eight to nine genes associated with polyamines metabolism, and eleven to eighteen genes, that are associated with polar lipids metabolism, were present in the genomes (Table 7).

Table 7.

Number of genes identified in biosynthetic pathwaya from whole genome sequences of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, AS15 and related organisms from the family Peptostreptococcaceae

| Genes responsible for biosynthesis | strain ACC19a | strain CM2 | strain CM5 | strain OBRC8 | strain AS15 | [Eubacterium] yurii subsp. margaretiae | Filifactor alocis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accession number | AFZE00000000 | AFZF00000000 | AFZG00000000 | ALNK00000000 | ALJM00000000 | AEES00000000 | CP002390 |

| Teichoic and lipoteichoic acids | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| Benzoquinones or naphthoquinones | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Polar lipids | 13 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 18 | 14 |

| Lipopolysaccharides | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mycolic acids | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Polyamines | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Diaminopimelic acid | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

aIdentified by Rapid Annotation Subsystem Technology (RAST)

Physiological and genomic characteristics of four novel isolates ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 were considerably different from the properties of strain AS15 and [E.] yurii subs. yurii, [E.] yurii subs. schtitka, and [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae [13, 14]. Strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8 were represented by highly motile peritrichous rods with round ends, single or in short chains; while strain AS15, [E.] yurii subs. yurii, [E.] yurii subs. schtitka, and [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae were straight rods with single subpolar flagellum and square ends, that formed rosettes or brush-like aggregates. Contrary to strain AS15, [E.] yurii subs. yurii, [E.] yurii subs. schtitka and [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae, strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 did not produce indole. In addition, strain AS15 showed alpha-hemolytic activity on blood TY-agar medium, while strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 were non-hemolytic. Metabolic end products of glucose fermentation of [E.] yurii subs. yurii and [E.] yurii subs. schtitka and [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae were butyrate, acetate and propionate; strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 produced acetate and propionate only.

DNA G + C content of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 was 30 – 30.68 %, while G + C of strain AS15, [E.] yurii subs. yurii and [E.] yurii subs. schtitka and [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae was 32 -32.24 %.

Conclusions

Unique phenotypic, phylogenetic, and genomic features allow for the differentiation of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 from strain AS15, [E.] yurii subs. yurii, [E.] yurii subs. schtitka, [E.] yurii subsp. margaretiae and F. alocis. Based on the distinct characteristics presented, we suggest that strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8 represent a novel genus and species within the family Peptostreptococcaceae, for which we propose the name Peptoanaerobacter stomatis gen. nov., sp. nov. The type strain is strain ACC19aT (=HM-483T; =DSM 28705T; =ATCC BAA-2665T).

Description of Peptoanaerobacter gen. nov.

Peptoanaerobacter (Gr. v. peptô, cook, digest; Gr. pref. an-, not; Gr. masc. n. aer, air; N.L. masc. n. bacter, rod, staff; N.L. masc. n. anaerobacter, the digesting rod not [living] in air).

Cells are Gram-positive, structurally and after staining, motile peritrichous rods with round ends, about 1.2 – 2.5 μm long and 0.4 – 0.8 μm wide, often occurring in chains. No spores are formed. Strictly anaerobic. Catalase, oxidase and urease are negative. Nitrate is not reduced. Growth is supported by yeast extract but not Casamino acids. Yeast extract is required for growth on glucose, sucrose and maltose. The major metabolic end-products of glucose fermentation are acetate and propionate. Growth temperature range is 30–42 oC. Major fatty acids are C14:0, C16:0, C16:1ω 7c. Genes responsible for biosynthesis of teichoic and lipoteichoic acids, polar lipids, polyamines and DAP are present in the genome. There are no genes responsible for biosynthesis of respiratory benzoquinones or naphthoquinones, mycolic acids or lipopolysaccharides. The type species is Peptoanaerobacter stomatis.

Description of Peptoanaerobacter stomatis sp. nov. Gr. n. stoma stomatos, mouth; N.L. gen. n. stomatis, of the mouth

Cell morphology is as described for the genus. Colonies are pin-point, circular, convex beige, 0.5 mm in diameter, and non-hemolytic. Acid is produced from glucose, maltose and sucrose, but not lactose, arabinose, cellobiose, mannose, melezitose, raffinose, rhamnose, trehalose, xylose, glycerol, mannitol, salicin and sorbitol. Indole is not produced. Gelatin is not liquefied. Esculin is not hydrolyzed. The type strain is susceptible to discs containing 1 mg kanamycin, 2 units penicillin, 60 μg erythromycin, 30 μg chloramphenicol, 30 μg tetracycline and bile. The genome is 2,541,543-bp long and contains 2,277 protein-coding and 54 RNA genes. DNA G + C content is 30.37 mol %. The type strain ACC19a (=DSM 28705T; =HM-483T; =ATCC BAA-2665T) was isolated from the human subgingival dental plaque. Habitat: human mouth.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grants 1RC1DE020707-01 and 3 R21 DE018026-02S1 to SSE, 1U54 AI84844-01 to KEN, U54HG004969 to AME, and HHSN272200900017C to the Broad Institute. We thank Dr. K. Konstantinidis for advice on ANI values calculations, Dr. W. Fowle, and T. Hohmann for help with electron microscopy, Drs. N. Panikov, and M. Mandalakis for fermentation products analysis, and A. Hazen for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- HMP

Human Microbiome Project

- HOMD

Human Oral Microbiome Database

- DDH

DNA-DNA hybridization

- BEI Resources

Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository

- DSMZ

Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH)

- GOLD

Genome On-Line Database

- IMG

Integrated Microbial Genomes

- RAST

Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology

Additional file

Associated MIGS records of Peptostreptococcaceae spp. ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8, and AS15.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: MVS SSE. Performed the experiments: MVS AC SND MT. Analyzed the data: MVS AC AME PAM JMM ASD. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: MT JMM ASD KEN AME SSE. Wrote the paper: MVS AC AME SSE. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Maria V. Sizova, Email: m.sizova@neu.edu

Amanda Chilaka, Email: chilaka.a@husky.neu.edu.

Ashlee M. Earl, Email: aearl@broadinstitute.org

Sebastian N. Doerfert, Email: doerfert@gmail.com

Paul A. Muller, Email: muller.pa@husky.neu.edu

Manolito Torralba, Email: mtorralba@jcvi.org.

Jamison M. McCorrison, Email: jmccorri@jcvi.org

A. Scott Durkin, Email: anthony.durkin@nih.gov.

Karen E. Nelson, Email: kenelson@jcvi.org

Slava S. Epstein, Email: s.epstein@neu.edu

References

- 1.Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, Paster BJ, Tanner AC, Yu WH, et al. The human oral microbiome. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(19):5002–17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(11):5721–32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bik EM, Long CD, Armitage GC, Loomer P, Emerson J, Mongodin EF, et al. Bacterial diversity in the oral cavity of 10 healthy individuals. ISME J. 2010;4(8):962–74. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroes I, Lepp PW, Relman DA. Bacterial diversity within the human subgingival crevice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(25):14547–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paster BJ, Olsen I, Aas JA, Dewhirst FE. The breadth of bacterial diversity in the human periodontal pocket and other oral sites. Periodontol 2000. 2006;42:80–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brook I, Frazier EH, Gher ME. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of periapical abscess. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1991;6(2):123–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1991.tb00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniluk T, Tokajuk G, Cylwik-Rokicka D, Rozkiewicz D, Zaremba ML, Stokowska W. Aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in subgingival and supragingival plaques of adult patients with periodontal disease. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51(Suppl 1):81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paster BJ, Boches SK, Galvin JL, Ericson RE, Lau CN, Levanos VA, et al. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(12):3770–83. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.12.3770-3783.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T, Yu WH, Izard J, Baranova OV, Lakshmanan A, Dewhirst FE. The Human Oral Microbiome Database: a web accessible resource for investigating oral microbe taxonomic and genomic information. Database. 2010;2010:baq013. doi: 10.1093/database/baq013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sizova MV, Hohmann T, Hazen A, Paster BJ, Halem SR, Murphy CM, et al. New approaches for isolation of previously uncultivated oral bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(1):194–203. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06813-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezaki T, et al. Family VII. Peptostreptococcaceae fam. nov. In: De Vos P, Garrity GM, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, et al., editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology Second ed. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 1008–13. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parte AC. LPSN–list of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D613–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margaret BS, Krywolap GN. Eubacterium yurii subsp. yurii sp. nov. and Eubacterium yurii subsp. margaretiae subsp. nov.: test tube brush bacteria from subgingival dental plaque. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1986;36(2):145–9. doi: 10.1099/00207713-36-2-145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margaret BS, Krywolap GN. Eubacterium yurii subsp. schtitka subsp. nov.: test tube brush bacteria from subgingival dental plaque. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38(2):207–8. doi: 10.1099/00207713-38-2-207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wade WG, et al. Genus I. Eubacterium. In: De Vos P, Garrity GM, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, et al., editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. 2. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 865–91. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, et al. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D346–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI Reference Sequence (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33:501-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Tatusova T, Ciufo S, Federhen S, Fedorov B, McVeigh R, O’Neill K, et al. Update on RefSeq microbial genomes resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D599–605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tatusova T, Ciufo S, Fedorov B, O’Neill K, Tolstoy I. RefSeq microbial genomes database: new representation and annotation strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D553–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lennon N, Lintner R, Anderson S, Alvarez P, Barry A, Brockman W et al. A scalable, fully automated process for construction of sequence-ready barcoded libraries for 454. Genome Biology. 2010;11:1-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Hyatt D, Chen G, Locascio P, Land M, Larimer F, Hauser L. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:1-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Checcucci A, Mengoni A. The integrated microbial genome resource of analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1231:289–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1720-4_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karp PD, Paley SM, Krummenacker M, Latendresse M, Dale JM, Lee TJ, et al. Pathway Tools version 13.0: integrated software for pathway/genome informatics and systems biology. Brief Bioinform. 2010;11(1):40–79. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbp043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caspi R, Altman T, Dreher K, Fulcher C, Subhraveti P, Keseler I, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:742–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caspi R, Altman T, Billington R, Dreher K, Foerster H, Fulcher CA, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of Pathway/Genome Databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D459–71. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tindall BJ, Rossello-Mora R, Busse HJ, Ludwig W, Kampfer P. Notes on the characterization of prokaryote strains for taxonomic purposes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60(Pt 1):249–66. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.016949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yarza P, Richter M, Peplies J, Euzeby J, Amann R, Schleifer KH, et al. The All-Species Living Tree project: a 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of all sequenced type strains. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2008;31(4):241–50. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auch AF, Klenk HP, Goker M. Standard operating procedure for calculating genome-to-genome distances based on high-scoring segment pairs. Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;2(1):142–8. doi: 10.4056/sigs.541628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auch AF, von Jan M, Klenk HP, Goker M. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;2(1):117–34. doi: 10.4056/sigs.531120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk HP, Goker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC bioinformatics. 2013;14:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gevers D, Cohan FM, Lawrence JG, Spratt BG, Coenye T, Feil EJ, et al. Opinion: Re-evaluating prokaryotic species. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(9):733–9. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Prokaryotic taxonomy and phylogeny in the genomic era: advancements and challenges ahead. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10(5):504–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(5):541–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(12):4576–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H, Whitman WB, et al. Revised road map to the phylum Firmicutes. In: De Vos P, Garrity GM, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, et al., editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. 2. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Gene Ontology Consortium Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D1049–56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]