To the Editor: Rickettsia felis, which belongs to the spotted fever group of rickettsiae, causes febrile illness in humans. The main vector of this bacterium is the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis). Since publication of reports of R. felis as a putative pathogen of humans in the United States in 1994, R. felis infection in humans worldwide has been increasingly described, especially in the Americas, Europe, Africa, and eastern Asia (1,2). R. felis infection is common among febrile patients (≈15%) in tropical Africa (3) and among apparently healthy persons in eastern coastal provinces of China (4). However, little is known about prevalence of R. felis infection of humans in southern Asia, although 3 serologically diagnosed cases in Sri Lanka have been described (5) and R. felis has been detected in rodent fleas in Afghanistan (6). Hence, we conducted a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh to explore the presence of rickettsial pathogens among patients with fever of unknown origin.

Study participants were 150 patients at Mymensingh Medical College (MMC) hospital in Mymensingh, north-central Bangladesh, from July 2012 through January 2014, and 30 healthy control participants from the staff at the same college. Selected patients met the following criteria: 1) fever (axillary temperature >37.5°C) for >15 days that did not respond to common antimicrobial drug therapy; 2) any additional clinical features including headache, rash, lymphadenopathy, myalgia, and eschars on skin; and 3) titer according to the Weil-Felix test (antibodies against any of 3 Proteus antigens) of >1:80. Patients with evident cause of fever (e.g., malaria diagnosed by blood smear or immunochromatography) were excluded from the study. This research was approved by the college institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from patients (or guardians) and healthy controls before their entry into the study.

Venous blood samples were aseptically collected from the patients, and DNA was extracted by conventional method by using proteinase K and sodium dodecyl sulfate. Nested PCR selective for the 17-kDa antigen gene was used to screen for rickettsiae according to the method described previously (7); ≈100 ng of DNA in a 50-μL reaction mixture was used. For each PCR, a negative control (water) was included and utmost care was taken to avoid contamination. Among the 150 samples tested, results were positive with a 232-bp amplified product for 69 (46%) and negative for all controls.

PCR products from 20 samples were randomly selected for sequence analysis. All nucleotide sequences from the 17-kDa antigen gene (186-bp) were identical to that of reference strain R. felis URRWXCa12 (GenBank accession no. CP000053). Among all 17-kDa–positive samples, positivity was further confirmed by PCR detection of the R. felis 16S rRNA gene and gltA in 95% and 75% of samples, respectively. Partial 16S rRNA gene sequences (305-bp) from 12 samples were 100% or 99% (10 and 2 samples, respectively) identical to that of R. felis URRWXCa12. The complete open reading frames of ompA (1773-bp), partial ompB (413-bp), and gltA (611-bp) sequences determined for 3, 3, and 5 samples, respectively, were also identical to those of R. felis URRWXCa12. The 5 gene sequences were determined for samples from 3 patients (2-year-old girl, 8-year-old boy, 17-year-old boy). The 5 gene sequences from the 2-year-old girl (strain Ric-MMC7) and 2 partial sequences of 16S rRNA (Ric-MMC71 and Ric-MMC133) were deposited in GenBank under accession nos. KP318088–KP318094.

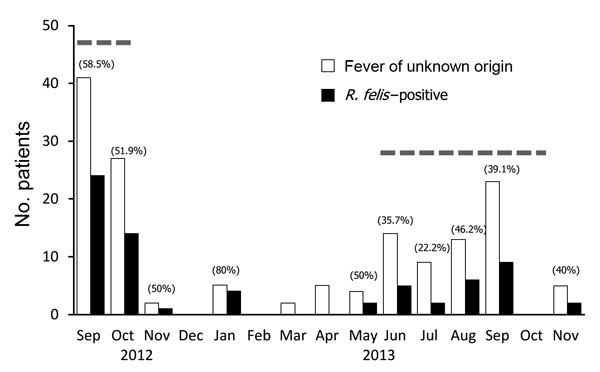

According to PCR, the positivity rate for the R. felis 17-kDa antigen gene was higher among male (54%, 40/74) than among female (38%, 29/76) patients and higher among patients in young and old age groups (0–15 years, 57%; 45–60 years, 62%) than among patients in other age groups (15–30 years, 41%; 30–45 years, 44%). During the study period, rates of R. felis positivity were highest during the late rainy season of 2012 (September [59%] and October [52%]) and lowest (0%) from December 2012 through April 2013 (Figure). The rate was significantly higher among farmers (76%, 13/17) than among persons of other occupations (e.g., housewives, teachers, students) (42%, 56/133); p = 0.016. Among the 69 rickettsiae-positive patients, headache and myalgia were reported by 29 (42%) and 17 (25%), respectively, whereas rash was detected in only 2 (3%) patients, both of whom were female.

Figure.

Number of patients with fever of unknown origin and Rickettsia felis–positive cases in the Mymensingh Medical College hospital, Bangladesh, 2012–2013. Numbers in parentheses indicate rates of R. felis positivity for each month; dashed lines indicate monsoon season (June–October).

This study demonstrated R. felis infection in patients in Bangladesh with unidentified febrile illness. The high prevalence (46%) of R. felis infection suggests that this infection is endemic to the north-central area of this country and might be associated with contact between humans of low socioeconomic status and the large number of stray cats and dogs. In contrast, the number of genetically confirmed cases of R. felis infection in humans reported to date in China, Taiwan, Thailand, and Laos have been very few (1,2,4,8–10), although widespread presence of this bacterium in cat fleas has been documented. For further confirmation of spread of this infectious disease, the prevalence of R. felis infections among humans, vectors, and reservoirs in other areas in Bangladesh and in other countries in southern Asia should be investigated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (grant no. 25305022) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Ferdouse F, Hossain A, Paul SK, Ahmed S, Mahmud MC, Ahmed R, et al. Rickettsia felis infection among humans, Bangladesh, 2012–2013 [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Aug [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2108.150328

References

- 1.Pérez-Osorio CE, Zavala-Velázquez JE, Arias León JJ, Zavala-Castro JE. Rickettsia felis as emergent global threat for humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1019–23 . . 10.3201/eid1407.071656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parola P. Rickettsia felis: from a rare disease in the USA to a common cause of fever in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:996–1000 . . 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mediannikov O, Socolovschi C, Edouard S, Fenollar F, Mouffok N, Bassene H, et al. Common epidemiology of Rickettsia felis infection and malaria, Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1775–83 . . 10.3201/eid1911.130361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Lu G, Kelly P, Zhang Z, Wei L, Yu D, et al. First report of Rickettsia felis in China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:682 . 10.1186/s12879-014-0682-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angelakis E, Munasinghe A, Yaddehige I, Liyanapathirana V, Thevanesam V, Bregliano A, et al. Detection of rickettsioses and Q fever in Sri Lanka. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:711–2 . . 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marié JL, Fournier PE, Rolain JM, Briolant S, Davoust B, Raoult D. Molecular detection of Bartonella quintana, B. elizabethae, B. koehlerae, B. doshiae, B. taylorii, and Rickettsia felis in rodent fleas collected in Kabul, Afghanistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:436–9. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schriefer ME, Sacci JB Jr, Dumler JS, Bullen MG, Azad AF. Identification of a novel rickettsial infection in a patient diagnosed with murine typhus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:949–54. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai CH, Chang LL, Lin JN, Tsai KH, Hung YC, Kuo LL, et al. Human spotted fever group rickettsioses are underappreciated in southern Taiwan, particularly for the species closely-related to Rickettsia felis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95810 . . 10.1371/journal.pone.0095810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edouard S, Bhengsri S, Dowell SF, Watt G, Parola P, Raoult D. Two human cases of Rickettsia felis infection, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1780–1 . . 10.3201/eid2010.140905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dittrich S, Phommasone K, Anantatat T, Panyanivong P, Slesak G, Blacksell SD, et al. Rickettsia felis infections and comorbid conditions, Laos, 2003–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1402–4 . . 10.3201/eid2008.131308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]