Abstract

Objective

Many patients with cancer search out information about their cancer on the internet, thus affecting their relationship with their oncologists. An in-depth analysis of patient–physician communication about information obtained from the internet is currently lacking.

Methods

We audio-recorded visits of patients with breast cancer and their oncologists where internet information was expected to be discussed. Inductive thematic text analysis was used to identify qualitative themes from these conversations.

Results

Twenty-one patients self-reported discussing cancer-related internet information (CRII) with their oncologists; 16 audio recordings contained detectable discussions of CRII and were analyzed. Results indicated that oncologists and patients initiated CRII discussions implicitly and explicitly. Oncologists responded positively to patient-initiated CRII discussions by (1) acknowledging their limited expertise/knowledge, (2) encouraging/approving using the internet as an information resource, (3) providing information/guidance on the proper use of internet searches, (4) discussing the pros and cons of relevant treatment options, or (5) giving information. Finally, patients reacted to the CRII discussions by (1) indicating that they only used reputable sources/websites, (2) asking for further explanation of information, (3) expressing continued concern, or (4) asking for the oncologist’s opinion or recommendation.

Conclusions

These results indicate that the majority of patients introduce internet information implicitly, in order to guard against any threat to their self-esteem. Physicians, in turn, seem to respond in a supportive fashion to reduce any threat experienced. Future interventions may consider providing prescription-based guidance on how to navigate the internet as a health information resource and to encourage patients to bring these topics up with their oncologist.

Background

According to the 2013 Pew Internet and American Life Project [1], 72% of American adults report using the internet to look up health information. Studies examining internet use among populations of patients with cancer have shown that 31–60% of patients with cancer and survivors as well as their caregivers have used the internet to look up cancer-related health information (CRII) [2–7], and this number is increasing [7]. Many patients with cancer (36–40%) indicate that they intend to discuss or have discussed this information with their physicians [8,9].

The increasing ability to access CRII of patients with cancer has the potential to affect patient–physician communication profoundly. Up to 44% of oncologists have reported having difficulty with these discussions [10]. Patients’ increasing ability to access disease and/or treatment information that was previously either unavailable or difficult to obtain may introduce a leveling effect on the power imbalance in the patient–physician relationship [11,12]. This leveling effect may increase patients’ abilities to be self-reliant. Alternatively, it could cause patients to question the physicians’ expertise and ability to diagnose and recommend certain treatments [13]. Moreover, access to CRII may lead to increases in patients’ levels of confusion and anxiety [10]. For instance, after reading CRII, some patients become overwhelmed, aware of conflicting medical information, and more nervous, anxious, and confused [8,9,14]. Additionally, access to CRII can lead to longer consultations [10]. While longer consultations may lead to better communication between patients and physicians, it can often frustrate physicians as a result of the limited time available to meet with each patient. Further, extended consultations may include unnecessary discussions that create additional tension within the patient–physician relationship [13].

A well-established literature on patient–physician communication has demonstrated that good patient–physician communication can improve patient satisfaction [15] and reduce patient anxiety [16]; yet, little research has focused on the impact that introduction of CRII can have on patient–physician communication processes. As such, it is important to understand how patients and physicians bring up and discuss these topics. Noting the importance of this research, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) recently highlighted the necessity for future research to investigate how the internet affects clinical communication [17].

Examining these patient–physician interactions from an interpersonal communication framework perspective can illuminate the communication occurring in these consultations. Facework theories [18–20], a set of interpersonal communication theories, provide a good conceptual framework for examining the patient–physician interactions in which CRII is introduced. Face is defined as ‘the conception of self that each person displays in particular interactions with others’ [21]. According to this theory, an individual’s communication may threaten his or her face, which is called a face-threatening act [19]. In turn, the conversational partner may respond in a manner that helps reduce this threat by supporting the other person’s face or they may further threaten the other person’s face. Following this framework, the patient’s introduction of CRII into the patient–physician consultation may threaten a patient’s face [22]. Then, physicians’ responses may serve to either support the patient’s face (by validating the patient’s efforts or taking the information seriously) or further threaten the patient’s face (by warning the patient about the dangers of the internet or disagreeing with the patient without validating his or her efforts). Supporting the use of this framework, prior research has indicated that patients with cancer have listed face-saving concerns as a reason for avoiding introduction of CRII [23].

To examine these interactions within a facework theoretical framework, it is necessary to observe patient–physician communication directly. Previous research has primarily examined the effect of internet information on patient–physician communication through surveys and interviews. Although informative, these research approaches are susceptible to biased recall. Direct observation of patient–physician communication about CRII would be a first step in helping to improve communication surrounding internet information and to establish effective communication strategies that facilitate these discussions. The goal of the present study was to observe the processes of patient–physician communication when CRII was discussed.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

In the present analyses, audio recordings of clinical consultations were examined in which CRII was discussed between an oncologist and a patient with breast cancer. Data from the audio-recorded patient–physician consultations included in the present study were part of a larger study examining patient–physician communication about CRII [24–26], which was approved by the institution’s IRB. In the larger study, patients were approached by a research assistant in the waiting room of breast medical oncology and surgery clinics at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between July 2008 and January 2010. Eligible patients for this study (1) had a breast cancer diagnosis, (2) were female, (3) were 21 years or older, and (4) spoke English.

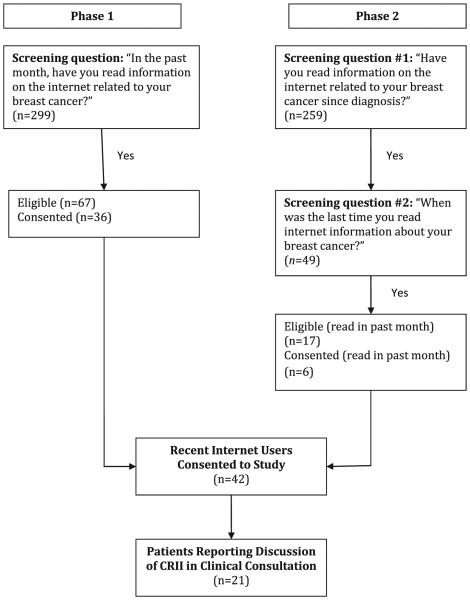

Recruitment occurred in two phases. In the first phase, 299 patients were approached. Of these, 67 patients responded that they had read about internet information in the past month and 36 (54%) consented to the study. In the second phase, recruitment strategies were broadened to include patients with a history of obtaining CRII, regardless of whether it was in the past month. Of the 259 patients approached, 49 acknowledged a history of CRII, and 17 patients indicated that they had read internet information related to their breast cancer within the past month. Of these 17 patients, 6 (35%) consented to the study. Combining both phases, a total of 42 patients were recruited to the portion of the study in which patient–physician clinical consultations were recorded. Of these 42 patients, 21 (50%) of the patients reported discussing CRII in their clinical consultations (refer to Figure 1). These were the 21 audio recordings analyzed for this study.1

Figure 1.

Patient flowchart for recruitment

Procedure

After consenting to the study, each participant completed questionnaires pre-consultation and post-consultation. Prior to their scheduled appointments, participants completed a questionnaire assessing sociodemographic information, intention to discuss internet information, topics intended to discuss, anxiety level, and physician reliance. The results on anxiety and physician reliance are reported elsewhere [24]. Patients had previously consented to have their clinical encounter audio recorded. On the day of the appointment, a research study assistant set up an audio recorder at the beginning of the appointment to record the clinical consultation. After the consultation, participants completed a questionnaire assessing whether they had discussed CRII with their oncologist. Finally, breast and surgical oncologists reported whether or not they were aware of a discussion occurring about CRII during the clinical consultation.

Data analysis

Data included 21 audio-recorded consultations of which the patient reported (post-consultation) that CRII was discussed. Each consultation was reviewed using inductive thematic text analysis in which conceptual findings emerge through an iterative process of transcript review, interpretation, and consensus discussions among coders [27–31]. The analysis procedure consisted of several phases and was completed by a pair of study investigators (MJS, RCD). Before coding, each analysis team member listened to the audio-recorded consultations and marked the time stamps for when discussions about CRII started and stopped. Analysts noted when more than one CRII discussion occurred within a single consultation and created separate time stamps for each. Patients’ pre-consultation questionnaires were utilized in identifying CRII discussions as they assessed topics that patients intended to discuss. The analysis team met to discuss differences in identifying CRII discussions and to reach consensus on time stamps. The analysis team then analyzed the transcripts of the CRII discussions.

In phase 1 of coding, analysis team members read each transcript individually, highlighting content deemed important and noting personal reactions and reflections in the margins of the text [32]. In phase 2, analysis team members transferred key findings and supporting quotes into an analysis template created for each transcript. In phase 3, team members met to share their independent thoughts, reflections, and observations and collectively generated a set of findings for each transcript. This iterative process was repeated until all transcripts of all consultations had been coded and synthesized into a summary of findings. In phase 4, the analysis team members reviewed the synthesized findings produced for each transcript and generated higher order descriptive and interpretive themes that represented prominent findings observed across all transcripts.

The salience of the findings identified in phase 4 was assessed in two ways. First, there was consideration of whether both analysis team members had reached similar conclusions regarding patient–physician communication tactics [33,34]. Second, the degree to which thematic findings recurred across consultations was assessed. The themes that were evident across the majority of the consultations were included in this study [33,35].

Results

The final sample included 21 audio-recorded patient–physician consultations. The analysis team could not detect CRII discussions for five of the consultations, even with the assistance of patients’ reported intended conversation topics. In two out of the five consultations in which discussion of CRII could not be detected, oncologists also did not detect the discussion. The majority (80%) of patients in this group were coming to a first time visit.

The 16 audio-recorded consultation transcripts in which discussions could be detected were qualitatively analyzed. Participants were predominantly Caucasian, married, and highly educated, with early stage, non-recurrent disease. They ranged between 27.5 and 73.2 years old (refer to Table 1 for all relevant demographic and clinical characteristics). The majority of patients (87.5%) reported intent to discuss CRII prior to their appointment. Oncologists detected discussion of CRII in these 16 consultations the majority of the time (75%). The majority of these patients (81.3%) were at a follow-up appointment. Qualitative analysis of the 16 consultations in which CRII was discussed revealed four broad themes: patient-initiated discussions of CRII, physician-initiated discussions of CRII, physician reactions to the initiation of a CRII discussion, and the patient reactions to the CRII discussion. Refer to Table 2 for a detailed description of each of these themes, which are discussed in detail in the succeeding texts.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics (N= 16)

| Study variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age | M = 55.5 years (SD = 10.7) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 14 (87.5%) |

| African American | 2 (12.5%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 2 (12.5%) |

| Married | 12 (75.0%) |

| Other | 2 (12.5%0 |

| Education level | |

| High school/technical degree | 4 (25.0%) |

| Undergraduate degree | 2 (12.5%) |

| Graduate degree | 10 (62.5%) |

| Disease characteristics | |

| Disease stage | |

| Stage I | 10 (62.5%) |

| Stage II | 2 (12.5%) |

| Stage III | 1 (6.3%) |

| Stage IV | 2 (18.8%) |

| Recurrent disease | 3 (18.8%) |

| Time since diagnosis | M = 5.0 years (SD = 5.9) |

| Visit characteristics | |

| Visit type | |

| Follow-up | 13 (81.3%) |

| New visit | 3 (18.8%) |

| Number of visits | M = 14.0 (SD = 16.9) |

| Time since first visit | M = 2.5 years (SD = 2.6) |

| Consultation characteristics | |

| Patient reported intent to discuss cancer-related internet information |

|

| Yes | 14 (87.5%) |

| No | 2 (12.5%) |

| MD report of patient discussing cancer-related internet information |

|

| Yes | 12 (75%) |

| No | 4 (25%) |

Table 2.

Definition of qualitative themes

| Theme | Definition |

|---|---|

| Introduction of cancer-related internet information | |

| Physician introduction of information | |

| Implicitly | Physicians implicitly refer to questions patients previously brought up or ask where patients found their source of information in order to bring up cancer-related internet information. |

| Explicitly | Physicians explicitly ask patients if they have any questions about cancer-related internet information. |

| Patient introduction of information | |

| Implicitly | Patients refer to cancer-related internet information (e.g. ask questions, confirm validity of information) without mentioning the source. |

| Explicitly | Patients directly ask questions or make statements referring to information that they self-disclose came from the internet. |

|

Physician response to the patient’s introduction of

cancer-related internet information |

|

| Acknowledge limited expertise/defer to someone else | Physicians respond to patient’s questions by indicating that the question is outside of their area of expertise. Most physicians then refer patients to speak with a specialist (e.g. radiologist) about their concerns and questions. |

| Encourage use of internet as information tool | Physicians praise patients’ initiative to look up cancer-related internet information and encourage them to keep doing so. |

| Provide information on proper use of internet sources | Physicians guide patients on how to utilize the internet as an information source by recommending specific websites, how to interpret findings, etc. |

| Reassure patient/give clarifying information | When patients indicate concern about negative side effects or outcomes they read about on the internet, physicians give additional information to clarify the benefits of treatment. |

| Ask follow-up questions | Physicians ask patients follow-up questions about the information they present (e.g. source of information, specific concerns, etc.) |

| Patient response to information given by physician | |

| Indicates that she only used reputable sources | Patients clarify that they only used reputable sources (e.g. Johns Hopkins, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) to look up information. |

| Asks for further explanation of information | Patients ask the physicians to explain further the information they presented. |

| Expresses continued concern | If concerned about the information being discussed, patients express concern. |

| Asks for doctor’s opinion or recommendation | Patients specifically ask physicians for specific recommendations or opinions about the cancer-related internet information discussed. |

Patient-initiated discussions of cancer-related internet information

In the majority of consultations (62.5%), patients introduced CRII either explicitly or implicitly. When introducing information explicitly, patients presented information they had read on the internet and then either asked the oncologist a question about the validity of that information (asking direct question) or left the discussion topic open for the oncologist to decide if he or she wanted to respond (direct statement).

I want just to reference online research, which I would have done anyway [laughs]. But I was reading about someone who had, you know who was talking about their symptoms for the Arimidex. And someone said that they weren’t, like, actually symptomatic for the first two years or so. Does that seem like too long? (Patient 03002)

Yeah I just put down…googled or whatever Lupron, you know? And it’s a lot. A lot of pages. Like how they [other patients] are suffering too bad to get Lupron…But I thought to myself maybe I made a mistake to go off Lupron just because…if hundreds and hundreds of ladies are complaining, you know, all like in pain and stuff. I don’t complain about hot flashes. I was just scared about bone density or whatever (Patient 01008).

When patients introduced information implicitly, they often introduced a cancer-related topic they had read about on the internet but did not overtly mention that this information came from the internet. Patients often vaguely referred to the experience of others when introducing information implicitly. Generally, these discussions were detected by coders’ mapping the discussion in the consultation on to the patients’ reported topic(s) they intended to discuss at their next appointment. This approach allowed patients to introduce information and ask questions without self-disclosing the information that came from the internet, which indicates that they engaged in a face-saving technique.

Ok, first of all, is it possible to get ovarian cancer if your ovaries have been removed? (Patient 01003)

Can I ask…If it turns out that I have lung damage from radiation, there is an experiment. I don’t know if you’ve heard of it. I think Duke University was doing it, that reduces damage after radiation (Patient 01007).

Physician-initiated discussions of cancer-related internet information

Although patients introduced CRII the majority of the time, physicians introduced CRII in a subset of 6 out of 16 consultations. Some oncologists introduced information implicitly, by referring back to a patient’s earlier comments that seemingly referenced the internet as an information source. This may have been done in an effort to address the question without threatening patient’s face through a direct confrontation about the source of the information.

Are you reading online chat sites? (Physician of patient 03002)

Ok. But…and then you were telling me that you read somewhere or you accessed? (Physician of patient 01008)

The second way oncologists introduced information was explicitly by directly asking patients if they had any questions about the internet. These encounters were more straightforward and most likely influenced by oncologists’ knowledge of the study’s focus on CRII. As such, this approach may be used less commonly in ordinary clinical encounters.

The other thing they asked me, too was if you had some internet information? (Physician of patient 07001)

…have you accessed the internet regarding questions? (Physician of patient 01001)

Physician response to the cancer-related internet information discussion

Once CRII was introduced into the conversation, physicians had an opportunity to respond to patients’ questions and statements regarding internet information. Most of the responses oncologists engaged in utilized techniques designed to strengthen the patient–physician relationship and help prevent patients from being embarrassed, indicating that physicians engaged in face-saving techniques. First, some oncologists simply acknowledged that they had limited expertise or knowledge on the topic being discussed and often referred the patient to a specialist.

Well, I actually can’t comment very much on, you know, those issues because it’s more, I think, surgical or plastic surgery more than our area (Physician of patient 01001).

I’m not familiar mainly because I’m not a radiation oncologist…So what you need to do is discuss these things with a radiation therapist (Physician of patient 01007).

A second way oncologists responded to the internet information was by promoting use of the internet by encouraging and/or approving the use of the internet as a resource for cancer-related information. For instance, in the following encounter, the oncologist encourages the patient to check information online about the medications she was taking:

Yes, checking even what we say…It’s very important, it’s very important (Physician of patient 03005).

Third, in order to improve the validity of the information patients received from the internet, oncologists provided guidance on the proper use of internet searches and tools in accessing CRII. For instance, the following oncologist gave explicit advice on how best to use the internet to look up CRII:

So when you’re looking at things on the internet, you have to really know the sites and know like what sites are at the top of the list just depends on the number of people who hit that particular link and so forth (Physician of patient 01008).

Fourth, the majority of oncologists attempted to reassure patients by giving clarifying information. Often, patients indicated that when they looked up symptoms or side effects of treatments, the outcome looked negative. To counter the extremely negative information patients often received via the internet, oncologists reminded them of the benefits that come with those treatment options. For example, in the following encounter, a patient initiated a discussion about internet information regarding potentially negative side effects of the hormone treatment she was on and expressed concern about experiencing these side effects. In response, the oncologist reassured the patient by telling her that although there are negative side effects to her hormone treatment, the overall benefit of having this treatment is increasing her chances at survival:

So yes it’s not pleasant to have hot flashes, it’s not pleasant to have vaginal dryness, and dry skin and all of those things. And many patients will say, ‘You’ve made an old woman out of me.’ But I think, keeping in mind, your age…the reason we started it is because of your young age – under 30. Having an estrogen-receptor positive tumor means that it’s hormone driven. And when you’re pre-menopausal, you’ve got a lot of estrogen around. And it may enhance the tamoxifen. I mean there’s European data saying that ovarian suppression and tamoxifen is better than tamoxifen alone (Physician of patient 01008).

Finally, in some cases, oncologists simply gave patients information or asked follow-up questions. In these encounters, oncologists seemed most concerned with exchange of information.

Patient reaction to the cancer-related internet information discussion

Patients responded to oncologists in a variety of ways that were seemingly aimed at avoiding threats to their face by appearing well-informed or seeking to gain additional information. First, several patients noted that the information they obtained came from a reputable source or website, reflecting a face-saving technique:

Well, I use Google, but then I only went to like NIH or…Sloan Kettering or something websites that came up on Google (Patient 05001).

Second, some patients asked for additional information and/or for the oncologist’s recommendation or opinion. In these cases, patients seemed concerned with clarifying the information they got from the internet and getting the oncologist’s expert opinion on the topic. These questions were very general as can be seen in the following examples in which patients followed up with information the oncologist gave in response to their original question.

So I don’t have to worry about ovarian cancer? You don’t think I have ovarian cancer? (Patient 01003)

So the fact that I’m tolerating it [treatment] is a, it’s a good sign? (Patient 03002)

Finally, instead of asking the oncologist for feedback or recommendations, some patients vocalized continued concern about the CRII they read. For instance, in the following example, the patient responds to the oncologist indicating that the treatment did not improve survival but improved response rates by stating continued concern over the treatment’s ability to prolong her life:

Well, it didn’t show improvement in the survival but they showed an improvement in the response rates, which is important (Physician of patient 01008).

But it doesn’t prolong your life (Patient 01008).

But I told you before prolonging your life also depends on what you have after that. So it’s not just that (Physician of patient 01008).

Conclusions

The present study provides detailed insight into patient–physician communication processes surrounding the introduction of CRII into clinical consultations. Analyses of the audio recordings revealed that patients (rather than oncologists) generally initiate CRII discussions. Specifically, in line with facework theories [18–20], the present study indicates that patients commonly engage in face-saving techniques, such as introducing CRII implicitly or explicitly noting that the information they looked up came from reputable sources. Oncologists, in turn, respond in ways that reduce this face threat by providing patients with information, encouraging them in their use of the internet, and taking the information introduced seriously [22]. For instance, many oncologists encouraged patients to access cancer-related information on the internet. Validating patients’ efforts to seek out information has been shown to be associated with higher patient satisfaction, validation, and reduced concern [22]. Similarly, encouraging patients’ use of CRII may lead to similar benefits.

Oncologists also attempted to improve patient care and aid in the decision-making process by providing detailed information. In line with past research, oncologists guided patients to appropriate internet health sources, in order to ensure that they were getting accurate and reliable information. This process has been referred to as ‘internet prescription’ [36]. In cases in which oncologists did not have direct answer to patients’ questions, they used these conversations as an opportunity to refer patients to the proper expert outlet. Finally, oncologists gave guidance and reassured patients who had looked up negative side effects of various drugs and/or treatments by highlighting the positive outcomes also associated with their treatment regimen.

Similar to oncologists, patients engaged these conversations positively. Although prior research indicates that providing patients with access to internet information may introduce a power leveling effect [11,12], the present study showed that patients approached oncologists as experts who could advise them about the information they found on the internet. Rather than directly challenging the oncologists [13], most patients approached them collaboratively and asked for their expert opinions and recommendations. This finding fits in line with previous research indicating that patients who discuss internet health information with their physicians report a reliance on their providers for decision-making [11]. Patients also often explicitly expressed that the information they looked up was from a reputable website. This strategy may have been used as a face-saving technique designed to overcome patients’ concerns about oncologists’ attributions about the source of information [23].

Limitations and directions for future research

One limitation of this study is the lack of diversity in this sample. It was a predominately Caucasian, well-educated, and higher income patient population that was composed of female patients. Future studies should examine more diverse patient populations to determine how these communication processes vary across race, gender, and socioeconomic status. It is possible, for instance, that men do not approach these communication topics in the same way that women do. For instance, men are more likely to report a positive seeking experience when looking up health information on the internet than women [37]. As such, there may be less anxiety and concern surrounding these conversations among men.

Another limitation of the present study is that the data are qualitative and thus cannot be used to formally test hypotheses. Although the qualitative analyses in the present study allowed for the detailed exploration of themes, they are not confirmatory in nature. As such, the results of the present study are limited in generalizability. Despite this limitation, the present results provide data that allow for the continued development of a communication process framework on the topic of CRII. Future work can build on this framework by utilizing content analysis systems and observer checklists to determine how frequently patients introduce CRII implicitly. Additionally, this research could examine which responses (by the physician) best addresses patients’ questions and concerns while also reducing the level of face threat experienced by patients in this situation. This research could help guide ‘best practice’ for how to discuss CRII with patients.

Finally, despite our best efforts to recruit patients, there was difficulty in recruiting patients who had read CRII. Of those who had read it, only 30% of them reported actually discussing CRII during their appointment. As such, the patient population in the present study was limited by a self-selection bias. As the amount of internet users searching for health information on the web continues to increase [7], up to 72% of all American internet users in 2013 [1], it is possible that these conversations have also become more commonplace. As such, future research should examine how these conversations have evolved and determine best practices for addressing this with patients.

Clinical implications

Because patients engaged in communication tactics indicative of face-saving techniques, oncologists should be sensitive to respond in ways that reduce face threat such as validating patients’ efforts and taking the information seriously [22]. Additionally, the present results also indicate that patients may be looking up CRII as a way to be actively involved in the treatment decision-making process rather than as a way to defy the oncologist’s power. As such, these conversations provide an excellent opportunity for oncologists to give their expert guidance and opinions. Rather than responding defensively, oncologists who elicit and validate CRII may help empower patients to be actively involved in their care [11,12,22]. Finally, the present study indicates that patients commonly introduce internet information implicitly, indicating that it may be advisable for oncologists to probe and ask patients if they have any questions about information they read on the internet. By providing a script in which patients can respond, oncologists may allow for a more formal and guided process of addressing inaccurate CRII. In conclusion, the discussions about CRII provide an opportunity in which oncologists can respond empathically, improve patient–provider communication, increase patient satisfaction, reduce anxiety, and clarify inaccurate information.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R03-CA130591 and T32-CA009461).

Footnotes

Note

Findings regarding the sources of the CRII discussed among the patients who discussed CRII with their physicians are published elsewhere [21], but the most commonly reported sources included government websites (e.g. NCI) (50%), hospital/cancer center websites (50%), and cancer organization websites (46%). As such, the majority of the information addressed in the present analyses refers to CRII coming from a reputable health website with accurate and reliable sources of information.

No listed authors have conflicts of interest associated with the work reported here.

References

- 1.Pew Forum Pew Internet and American Life Project. 2013 (Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/health-fact-sheet/

- 2.Basch EM, Thaler HT, Shi W, Yakren S, Schrag D. Use of information resources by patients with cancer and their companions. Cancer. 2004;100(11):2476–2483. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monnier J, Laken M, Carter CL. Patient and caregiver interest in internet-based cancer services. Cancer Pract. 2002;10(6):305–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.106005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranson S, Morrow GR, Dakhil S, et al. Internet use among 1020 cancer patients assessed in community practices: a URCC CCOP study. Paper presented at: Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metz JM, Devine P, DeNittis A, et al. A multi-institutional study of internet utilization by radiation oncology patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56(4):1201–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bylund CL, Gueguen JA, D’Agostino TA, Li Y, Sonet E. Doctor–patient communication about cancer-related internet information. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010;28(2):127–142. doi: 10.1080/07347330903570495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou W-yS, Liu B, Post S, Hesse B. Health-related internet use among cancer survivors: data from the Health Information National Trends Survey, 2003–2008. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(3):263–270. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabel MS, Strecher VJ, Schwartz JL, et al. Patterns of internet use and impact on patients with melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5):779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helft PR, Eckles RE, Johnson-Calley CS, Daugherty CK. Use of the internet to obtain cancer information among cancer patients at an urban county hospital. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):4954–4962. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helft PR, Hlubocky F, Daugherty CK. American oncologists’ views of internet use by cancer patients: a mail survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology members. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(5):942–947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bylund CL, Sabee CM, Imes RS, Aldridge SA. Exploration of the construct of reliance among patients who talk with their providers about internet information. J Health Commun. 2007;12(1):17–28. doi: 10.1080/10810730601091318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akoul GM. Perpetuating passivity: reliance and reciprocal determinism in physician-patient interaction. J Health Commun. 1998;3(3):233–259. doi: 10.1080/108107398127355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broom A. Medical specialists’ accounts of the impact of the internet on the doctor/patient relationship. Health. 2005;9(3):319–338. doi: 10.1177/1363459305052903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleisher L, Bass S, Ruzek S, McKeown-Conn N. Relationships among internet health information use, patient behavior and self-efficacy in newly diagnosed cancer patients who contact the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Atlantic Region Cancer Information Service (CIS) Paper presented at: AMIA Annual Fall Symposium. 2002 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewin S, Skea Z, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4(10):1–62. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):371–371. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein R, Street RL. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller K. Communication theories. McGraw-Hill; Boston: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown P. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goffman E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday; Garden City, NY: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cupach WR, Metts S. Facework. Vol. 7. London. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bylund CL, Gueguen JA, Sabee CM, Imes RS, Li Y, Sanford AA. Provider–patient dialogue about Internet health information: an exploration of strategies to improve the provider–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imes RS, Bylund CL, Sabee CM, Routsong TR, Sanford AA. Patients’ reasons for refraining from discussing internet health information with their healthcare providers. Health Commun. 2008;23(6):538–547. doi: 10.1080/10410230802460580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Agostino TA, Ostroff JS, Heerdt A, Dickler M, Li Y, Bylund CL. Toward a greater understanding of breast cancer patients’ decisions to discuss cancer-related internet information with their doctors: an exploratory study. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(1):109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bylund CL, D’Agostino TA, Ostroff J, Heerdt A, Li Y, Dickler M. Exposure to and intention to discuss cancer-related internet information among patients with breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(1):40–45. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maloney E, D’Agostino T, Heerdt A, et al. Sources and types of online information that breast cancer patients read and discuss with their doctors. Palliat Support Care. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000862. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard H. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. AltaMira; Lanham, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:1189–1208. 5 Pt 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren CA, Karner TX. Discovering Qualitative Methods: Field Research, Interviews, and Analysis. Roxbury; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guba EG. Toward a Methodology of Naturalistic Inquiry in Educational Evaluation. Center for the Study of Evaluation, UCLA Graduate School of Education, UCLA; Los Angeles, CA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMullan M. Patients using the internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient–health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(1):24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ybarra M, Suman M. Reasons, assessments and actions taken: sex and age differences in uses of Internet health information. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(3):512–521. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]