Abstract

Hepatic tuberculosis (TB) is usually associated with pulmonary or miliary TB, but primary hepatic TB is very uncommon even in countries with high prevalence of TB. The clinical manifestation of primary hepatic TB is atypical and imaging modalities are unhelpful for differential diagnosis of the liver mass. Image-guided needle biopsy is the best diagnostic method for primary hepatic TB. In the cases presented here, we did not perform liver biopsy because we believed the liver masses were cholangiocarcinoma, but primary hepatic TB was ultimately confirmed by postoperative pathology. Here we report two cases of patients who were diagnosed with primary hepatic TB mimicking mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Hepatectomy, Cholangiocarcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is known to involve the liver in different ways. Hepatic involvement in TB as part of disseminated TB is seen in up to 50%-80% of cases. However, hepatic TB, particularly in the absence of miliary TB, is rare and represents less than 1% of all cases of TB [1]. Hepatic TB lacks typical clinical manifestations and can be difficult to differentiate from other malignancies such as hepatocellular carcinoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA), klatskin tumor, and liver abscess using imaging modalities. Therefore, primary hepatic TB can be easily misdiagnosed [2]. Here, we report two cases of primary hepatic TB mimicking mass-forming iCCA.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

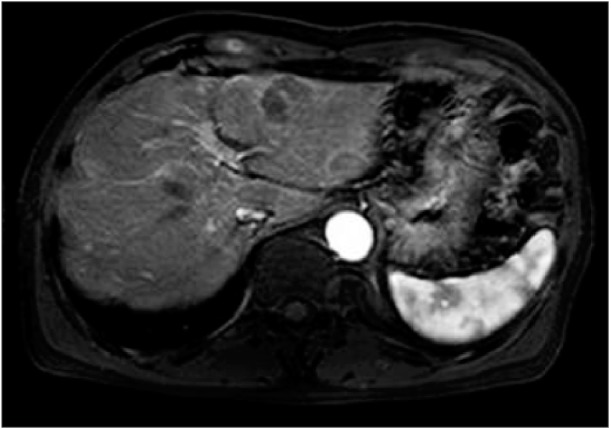

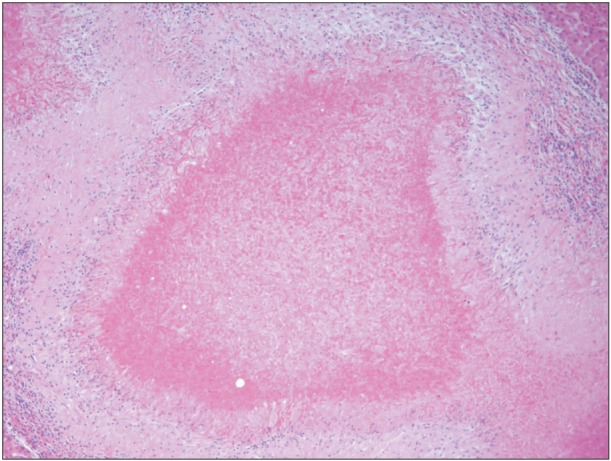

A 77-year-old male was referred to Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, for a liver mass on ultrasonography (US). His laboratory tests were all normal. His serum α-FP, CEA, and CA 19-9 levels were within normal limits. The patient had no previous history of TB. Chest x-ray showed no opacities and abdominal CT showed a 3-cm hypodense mass with weak peripheral enhancement in the arterial and portal phase with focal peripheral intrahepatic bile duct dilatation. Liver MRI showed a well-defined liver mass with peripheral rim enhancement on dynamic images in the lateral segment of the liver (Fig. 1). Mass-forming iCCA was highly suspected. He underwent left lateral sectionectomy of the liver. Histologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation with extensive caseating central necrosis (Fig. 2). Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear test and PCR assay for Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Quantiferon-TB test were all negative. We discussed antituberculous medication for this patient with a physician at the Division of Infectious Diseases. Thus, antituberculous treatment with isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide and levofloxacin was administered for 1 year. The patient is doing well now.

Fig. 1. MRI shows relatively well defined mass (3.0 cm × 2.7 cm) on arterial phase, peripheral rim like enhancement with mainly nonenhancing lesion.

Fig. 2. The presence of centrally necrotic caseating granuloma (H&E, ×40) in the liver parenchyma.

Case 2

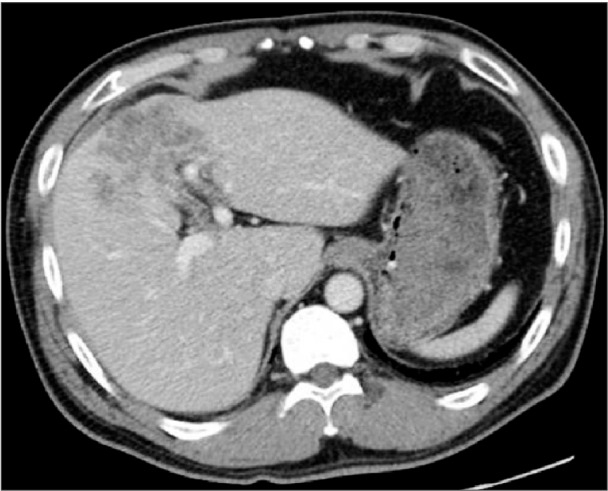

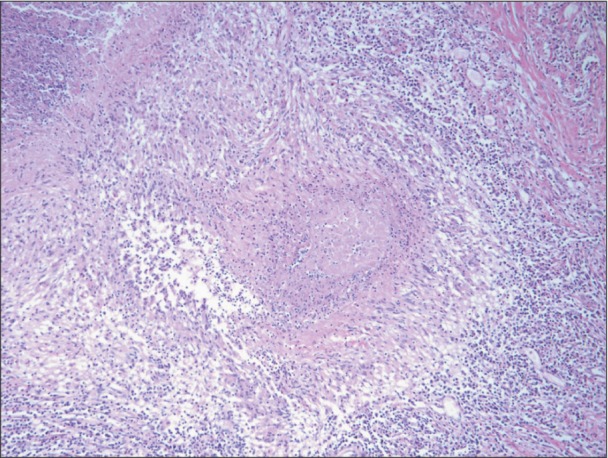

A 61-year-old male was admitted to Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, complaining of right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain that had started 1 month earlier. The patient had no previous history of TB. His laboratory tests were all normal except for leukocytosis (10,900/nm3) and an increased CRP level (5.17 mg/dL). His serum α-FP and CA 19-9 levels were within normal limits. His chest x-ray showed no lesions suggestive of TB. Abdominal CT showed a 7-cm hypodense lesion with slight peripheral enhancement in the portal phase with focal peripheral intrahepatic bile duct dilatation (Fig. 3). MRI showed a multilobulated liver mass with early arterial peripheral enhancement and delayed gradual enhancement in segment 4 of the liver as well as extrahepatic invasion to the adjacent transverse colon. Mass-forming iCCA was strongly suspected, so the patient underwent PET/CT to check for metastasis. PET showed a fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid mass and multiple hepatoduodenal lymph nodes. Based on the CT, MRI, and F-18 FDG PET/CT findings, we strongly suspected iCCA and consequently performed left hemihepatectomy and segmental resection of the transverse colon. Pathologic examination revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation with extensive caseating necrosis (Fig. 4). AFB smear test and M. tuberculosis DNA by PCR analysis were negative, but the Quantiferon-TB test was positive. Antituberculous treatment with isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide and levofloxacin was started and continues at this time. The patient is doing well after 9 months of follow-up.

Fig. 3. CT shows a large lobulated mass (7.0 cm × 3.5 cm) in segment 4 with mild heterogenous enhancement and focal peripheral intrahepatic duct dilatation.

Fig. 4. The presence of centrally necrotic caseating granuloma (H&E, ×40) in normal liver parenchyma.

DISCUSSION

TB in the liver is always secondary to TB elsewhere. Primary hepatic TB is used in the sense that a TB lesion in the liver may result from tubercle bacilli gaining access to the portal vein from a microscopic or small TB focus in the bowel, with subsequent healing taking place at the site of entry and leaving no trace of it [3]. The clinical classification and nomenclature of hepatic TB are confusing in the literature. Levine classified TB into: (1) miliary TB; (2) pulmonary TB with hepatic involvement; (3) primary liver TB; (4) focal tuberculoma or abscess; and (5) TB cholangitis [4]. The most common form of hepatic involvement is the miliary form of TB. It is believed that the route of transmission is different in miliary TB and primary hepatic TB. In the miliary form of TB, hematogenous dissemination of the bacteria seems to be the route of dissemination, while in primary hepatic TB, the tubercle bacillus reaches the liver through the portal vein from the intestine. Because low oxygen tension in the liver is unfavorable for mycobacteria growth [2], primary hepatic TB was observed in about 1% of hepatic TB cases. On the other hand, hepatic involvement can be seen in nearly 70% of disseminated cases of TB [1]. Hepatic TB lacks typical clinical manifestations as well as a typical imaging result. The most frequently presented clinical and laboratory findings in primary hepatic TB are fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, hepatomegaly and elevated alkaline phophaphatase level [1]. In our cases, one patient complained of RUQ pain and both patients were within normal limits of ALP levels. On CT scans, hepatic TB shows a nonenhancing, central, low density lesion owing to caseation necrosis with a slightly enhancing peripheral rim corresponding to surrounding granulation tissue. MRI of hepatic TB shows a hypointense nodule with a hypointense rim on T1-weighted imaging. T2-weighted imaging shows a hypointense, isointense or hyperintense nodule with a less intense rim [2]. However, imaging features of hepatic TB might be multiple lesions of varying density, indicating that there are lesions in different pathologic stages coexisting in hepatic TB, including TB granuloma, liquefaction necrosis, fibrosis or calcification [3]. Therefore, It is very difficult to differentially diagnose using imaging modalities primary hepatic TB from iCCA. Hepatic TB also shows FDG-avidity on F-18 FDG PET/CT similar to other malignant tumors [5]. F-18 FDG PET/CT is also less useful in differentiating hepatic TB from other hepatic necrotic masses because FDG-avidity can also been seen in necrotic tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma, iCCA, and metastatic carcinoma. Clinical manifestations, laboratory findings, and imaging studies are varied and nonspecific, so pathologic examination of liver lesions is essential to confirm hepatic TB. Therefore, percutaneous fine needle biopsy is an excellent diagnostic method. In our cases, we believed the hepatic mass was iCCA without doubt because both tumors showed typical imaging features of iCCA. Moreover, according to the guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic CCC, a presumed radiographic diagnosis is sufficient in noncirrhotic patients in whom a decision has been made to proceed with surgical resection [6]. In addition, after consideration of the risks associated with percutaneous needle biopsy such as bleeding and tumor dissemination, needle biopsy was not recommended for the two patients. Eventually, the patients were preoperatively misdiagnosed with iCCA, and we later confirmed primary hepatic TB by postoperative pathology. It is most ideal to demonstrate AFB in the liver biopsy specimen, because AFB is most easily found in caseaous necrosis. However, the sensitivity of staining for AFB is low (0%-45%) and culture is also low (10%-60%). PCR directly detects the presence of M. tuberculosis, which is more useful for diagnosis of TB, but the positivity rate is 57% [4,7,8]. For these reasons, the absence of AFB does not necessarily exclude TB, particularly in endemic areas of TB [8]. Therefore, even without finding tubercle bacillus, the presence of a caseating granuloma in histologic examination is diagnostic. In our cases, AFB smear test, culture, and PCR assay for M. tuberculosis were all negative. We performed the Quantiferon-TB test that was reported to more accurately determine the risk for latent TB infection [9], but only one patient showed a positive result in the Quantiferon-TB test. However, caseating granuloma was revealed in the liver specimens of both patients, so we were able to reach the diagnosis of hepatic TB. A review of 96 patients with hepatic TB revealed histological findings of granuloma (95.8%), caseation (83.3%), and AFB in association with granuloma (9%) [10]. As described earlier, because low oxygen tension in the liver is unfavorable for the growth of mycobacteria, tubercle bacilli are very rarely encountered in hepatic TB [2]. Even in situations where the patient has undergone a surgical procedure before diagnosis or where the PCR and staining are negative, a rationale exists for antituberculosis treatment for residual disease. In summary, primary hepatic TB is very uncommon, lacks typical symptoms, signs and laboratory findings. It is difficult to diagnose primary hepatic TB using imaging modalities because the imaging features of the hepatic TB are various and nonspecific. In patients with most frequent systemic manifestations of TB such as high fever, weight loss, RUQ pain and hepatosplenomegaly, suspicion of hepatic TB for differential diagnosis is important especially in endemic areas. For definite diagnosis of primary hepatic TB, percutaneous needle biopsy would be the most useful diagnostic tool.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Mert A, Ozaras R, Tabak F, Ozturk R, Bilir M. Localized hepatic tuberculosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2003;14:511–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, Wang WL, Zhu Y, Cheng JW, Dong J, Li MX, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic tuberculosis: report of five cases and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6:845–850. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hersch C. Tuberculosis of the liver: a study of 200 cases. S Afr Med J. 1964;38:857–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine C. Primary macronodular hepatic tuberculosis: US and CT appearances. Gastrointest Radiol. 1990;15:307–309. doi: 10.1007/BF01888805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang YT, Lu F, Zhu F, Qian ZB, Xu YP, Meng T. Primary hepatic tuberculoma appears similar to hepatic malignancy on F-18 FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34:528–529. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181abb6f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridgewater J, Galle PR, Khan SA, Llovet JM, Park JW, Patel T, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1268–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen HC, Chao YC, Shyu RY, Hsieh TY. Isolated tuberculous liver abscesses with multiple hyperechoic masses on ultrasound: a case report and review of the literature. Liver Int. 2003;23:346–350. doi: 10.1034/j.1478-3231.2003.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang WT, Wang CC, Chen WJ, Cheng YF, Eng HL. The nodular form of hepatic tuberculosis: a review with five additional new cases. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:835–839. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.11.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mardani M, Farshidpour M, Nekoonam M, Varahram F, Najafizadeh K, Mohammadi N, et al. Performance of QuantiFERON TB gold test compared with the tuberculin skin test for detecting latent tuberculosis infection in lung and heart transplant candidates. Exp Clin Transplant. 2014;12:129–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Essop AR, Posen JA, Hodkinson JH, Segal I. Tuberculosis hepatitis: a clinical review of 96 cases. Q J Med. 1984;53:465–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]