Abstract

Members of the cytochrome P450 CYP2J subfamily are expressed in multiple tissues in mice and humans. These enzymes are active in the metabolism of fatty acids to generate bioactive compounds. Herein we report new methods and results for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis for the seven genes (Cyp2j5, Cyp2j6, Cyp2j8, Cyp2j9, Cyp2j11, Cyp2j12, and Cyp2j13) of the mouse Cyp2j subfamily. SYBR Green primer sets were developed and compared with commercially available TaqMan primer/probe assays for specificity toward mouse Cyp2j cDNA, and analysis of tissue distribution and regulation of Cyp2j genes. Each TaqMan primer/probe set and SYBR Green primer set were shown to be specific for their intended mouse Cyp2j cDNA. Tissue distribution of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms confirmed similar patterns of expression between the two qPCR methods. Cyp2j5 and Cyp2j13 were highly expressed in male kidneys, and Cyp2j11 was highly expressed in both male and female kidneys. Cyp2j6 was expressed in multiple tissues, with the highest expression in the small intestine and duodenum. Cyp2j8 was detected in various tissues, with highest expression found in the skin. Cyp2j9 was highly expressed in the brain, liver, and lung. Cyp2j12 was predominately expressed in the brain. We also determined the Cyp2j isoform expression in Cyp2j5 knockout mice to determine whether there was compensatory regulation of other Cyp2j isoforms, and we assessed Cyp2j isoform regulation during various inflammatory models, including influenza A, bacterial lipopolysaccharide, house dust mite allergen, and corn pollen. Both qPCR methods detected similar suppression of Cyp2j6 and Cyp2j9 during inflammation in the lung.

Introduction

The cytochrome P450 (P450) gene superfamily includes enzymes that catalyze the metabolism of a wide range of xenobiotics and endogenous compounds (Nelson et al., 1996; Nebert and Russell, 2002; Kroetz and Zeldin, 2002). Arachidonic acid (AA) is a polyunsaturated fatty acid present in mammalian cell membranes that can be epoxygenated to bioactive epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) or hydroxylated to hydroxyeicosatraenoic acids by various P450 enzymes (Capdevila et al., 2000; Nebert and Russell, 2002; Kroetz and Zeldin, 2002). EETs exhibit potent vasodilatory (Campbell et al., 1996; Larsen et al., 2006), anti-inflammatory (Node et al., 1999), cardioprotective (Seubert et al., 2004, 2006), fibrinolytic (Node et al., 2001), and angiogenic (Wang et al., 2005) effects both in vitro and in vivo.

Mouse Cyp2j subfamily members are active in the metabolism of AA and other substrates (Ma et al., 1999; Qu et al., 2001; Ma et al., 2002; Graves et al., 2013). The majority of P450 enzymes are abundantly expressed in the liver, but the mouse Cyp2j subfamily members are predominantly found in extrahepatic tissues. Previous studies indicated that Cyp2j5, Cyp2j8, Cyp2j11, and Cyp2j13 are predominantly expressed in the kidney ( Ma et al., 1999; Graves et al., 2013), Cyp2j6 transcripts are primarily detected in the intestine (Scarborough et al., 1999), and Cyp2j8, Cyp2j9, and Cyp2j12 transcripts are highly expressed in the brain (Qu et al., 2001; Graves et al., 2013). These previous studies have all used nonquantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to detect the presence or absence of mouse Cyp2j transcripts in tissue.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) is a powerful and accurate tool to measure gene expression. While RT-PCR allows for the detection of a transcript, the ability of qPCR to monitor the amplification of target sequences in real time allows for the quantification of transcript levels. All qPCR assays rely on cDNA-specific primer pairs to amplify a unique target sequence from transcripts of interest. The real-time detection of the PCR reaction is typically quantified in one of two ways. One method relies on a double-stranded DNA-binding dye (e.g., SYBR Green) to serve as a reporter (Ponchel et al., 2003). The other common method of quantifying the PCR reaction in real time is the use of a fluorescently labeled transcript-specific oligo/probe (e.g., TaqMan and Quantifast assays). These primer/probe assays rely on the endonuclease activity of Taq polymerase to cleave the fluorophore from the probe, which has a covalently attached fluorescent quencher (Heid et al., 1996).

Both methods of detection have advantages and disadvantages. One drawback of both methods becomes evident in the quantification of evolutionarily related genes such as the Cyp2j subfamily members. SYBR Green–based assays report the abundance of double-stranded DNA, which is potentially confounded by homology between related transcripts and thus resulting in multiple off-target amplicons being produced. Conducting an end-point melting curve assay after a SYBR Green assay is critical to confirm that the fluorescence measured is due to a unique target sequence amplicon rather than multiple products being produced from unintended transcripts.

Primer/probe assays have increased sensitivity due to the target-specific fluorescent probe, but they lack the end-point confirmation that the measured fluorescence is due to amplification of the desired amplicon. This is especially problematic when quantitating highly conserved paralogs such as the Cyp2j subfamily members. Accurate qPCR of the mouse Cyp2j subfamily members will allow for assessment of their tissue distribution and aid in elucidating their biologic function and regulation. Developing specific primer sets for use with the SYBR Green reporter can be challenging due to nucleotide coding sequence homology (75%–88% identity) between the subfamily members (Graves et al., 2013).

This study developed primer sets for qPCR use with the SYBR Green dye based on the published and cloned cDNA sequence of the mouse Cyp2j subfamily members. These were compared with commercially available TaqMan primer/probe sets for qPCR. Each of the SYBR Green primer sets and the TaqMan primer/probes were found to be specific for their intended transcript. Similar tissue distributions were observed for both qPCR methods for all seven Cyp2j isoforms. In addition, both qPCR methods were used to quantify the expression of the Cyp2j subfamily members in the kidney of Cyp2j5 knockout (KO) mice to determine whether compensatory changes in Cyp2j expression exist. Lastly, the levels of Cyp2js were determined in several inflammatory models, including influenza A, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), house dust mite (HDM), and corn pollen.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Supplies.

SYBR Green primer set oligonucleotides were synthesized by BioServe BioTechnologies (Laurel, MD) and Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). TaqMan primer/probe assays, MicroAmp Optical 384-Well Reaction Plates, and an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System were from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA).

Animal Treatment.

All animal experiments were performed according to the National Institute of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee.

For tissue distribution assessment, total RNA was prepared from tissues collected from three female and three male wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice using RNeasy Midi or Mini Kits from Qiagen (Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For the experiments using Cyp2j5 KO mice, RNA was prepared from four female and four male Cyp2j5 KO and WT kidneys.

For the influenza exposure study, WT male and female C57BL/6 mice were infected with 200 plaque-forming units of influenza A/Hong Kong/8/68 (H3N2) in a total volume of 50 μl by intranasal instillation. Lungs were collected 4 days after infection, and the total RNA was isolated.

For the LPS studies, WT male C57BL/6 mice were given a single dose of 50 μg of LPS intranasally. After 4 hours, the mice were euthanized, the lungs were collected, and the RNA was isolated.

For the HDM experiments, male C57BL/6 mice were sensitized with 10 μg of HDM allergen in 50 μl of saline via oropharyngeal aspiration on days 1 and 8, followed by challenge on days 15, 16, and 17 with 2 μg of HDM in 50 μl of saline via oropharyngeal aspiration. Lungs were collected on day 18, and the total RNA was isolated.

For acute corn pollen exposure experiments, female BALB/C mice were given a single dose of 4 mg of corn pollen in 75 μl of phosphate-buffered saline by aspiration. At 24 hours after dosing, the mice were euthanized, the lungs were collected, and the RNA was isolated. For chronic corn pollen exposure experiments, female BALB/C mice were given 1 mg of corn pollen in 75 μl of phosphate-buffered saline by aspiration for 7 consecutive days. The mice were euthanized 24 hours after the last dose of corn pollen, the lungs were collected, and the total RNA was isolated. Saline controls were included in both acute and chronic corn pollen exposure experiments.

cDNA Synthesis.

For each experimental animal, 1 μg of total RNA was treated with 1 unit of DNase I (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 15 minutes. DNase I was inactivated by addition of 1 μl of 25 mM EDTA and heat treatment at 65°C for 10 minutes. RNase-free water was added to bring each sample to a total volume of 50 μl. The High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit from Life Technologies was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to produce cDNA from the DNase I–treated RNA. The final concentration of the cDNA was 10 ng/μl. The cDNA was diluted to a working concentration of 1 ng/μl with RNase-free water.

TaqMan qPCR.

TaqMan primer/probes for mouse Cyp2j subfamily members were purchased from Life Technologies and are listed in Table 1. For all qPCR reactions, 0.5 μl of the 20X primer/probes were used in a 10 μl total reaction volume. Maxima Probe/ROX qPCR Master Mix (2X) from Thermo Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) was used in the qPCR master mix. The PCR conditions used were as follows: 50°C for 2 minutes; 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 repeat cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, and 60°C for 1 minute. Samples were run in triplicate.

TABLE 1.

TaqMan primer/probes for the mouse Cyp2j subfamily

| Subfamily Member | TaqMan Primer/Probe |

|---|---|

| Cyp2j5 | Mm00487292_m1 |

| Cyp2j6 | Mm01268197_m1 |

| Cyp2j8 | Mm03412388_m1 |

| Cyp2j9 | Mm00466426_m1 |

| Cyp2j11 | Mm01268190_m1 |

| Cyp2j12 | Mm01262103_m1 |

| Cyp2j13 | Mm00523816_m1 |

| Gapdh | Mm99999915_g1 |

| 18s | Mm03928990_g1 |

SYBR Green qPCR.

Specific primer sets of oligonucleotides were designed, spanning exon/exon boundaries if possible, for the mouse Cyp2j subfamily members (Table 2). Some primer sets were those that had previously been published for use in nonquantitative RT-PCR (Ma et al., 1999; Graves et al., 2013). All primers were diluted to a concentration of 10 μM, and 0.5 μl was used in a total volume of 10 μl for the qPCR reactions. Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix from Applied Biosystems by Life Technologies was used for all the SYBR Green qPCR reactions. The PCR conditions used were as follows: 50°C for 2 minutes; 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 repeat cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, then 60°C for 1 minute. A dissociation stage of 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 15 seconds, and 95°C for 15 seconds was added. For the Cyp2j6, Cyp2j9, Cyp2j12, and Cyp2j13 primer sets an annealing/extension temperature of 64°C was used. All samples were run in triplicate.

TABLE 2.

SYBR Green primer set sequences for the mouse Cyp2j subfamily

| Transcript | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyp2j5 | ATCAGAGAAGCGAAAAGAATGTAG | CCATTTCCTCTGATTCTGACTCAT | Ma et al., 1999 |

| Cyp2j6 | GGACCTCTTCTTTGCTGGAACAG | GCAAGTCTTGCTGCCCTCTTCT | |

| Cyp2j8 | TTGGGGATCCAGCCGTTTGT | TGAGCCTCATCCTGTATGCGT | |

| Cyp2j9 | AACCGTTTCCCCAGTCAGTC | ATTGCACGCACTCTCTGTCA | |

| Cyp2j11 | ATTGGAGTATGCCCTGAAGAT | GTGATGGCCCATTACTTGAGG | Graves et al., 2013 |

| Cyp2j12 | AAGGAGGCTGACTGTCTTGTGG | GACTGTCCTCATACTCAAAGCGC | |

| Cyp2j13 | GTCACTGAGCCACTGCCCATA | GTCTCATCTTGGGCACGAACC | Graves et al., 2013 |

| Gapdh | TTGATGGCAACAATCTCCAC | CGTCCCGTAGACAAAATGGT | |

| 18s | TCGTATTGCGCCGCTAGAGGT | GGGTCATGGGAATAACGCCGC | |

| β-lactamases | CGCAGAAGTGGTCCTGCAAC | TCTGCTATGTGGCGCGGTAT |

qPCR Analysis.

Data generated from the qPCR reactions were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). All graphs were generated using the GraphPad Prism 6.0C program (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Most mouse tissue expression values were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh). The cloned cDNAs for SYBR Green were normalized to plasmid control β-lactamase levels. There were significant increases in the relative expression of Gapdh, β2-microglobulin (B2m), and β-actin in the influenza A–treated mice compared with saline controls; therefore, 18s rRNA was used as the housekeeping gene for this experiment (Supplemental Fig. 1).

For the HDM and corn pollen studies, the relative expression of Gapdh, B2m, actin, and 18s housekeeping genes were significantly decreased in the treated versus saline control (Supplemental Figs. 2 and 3). For these two studies all the CT values for the experiment were averaged and used to calculate individual sample ΔCT. The average ΔCT values of the control group were used to calculate the ΔΔCT values for individual samples. Samples below the limit of detection (CT > 38) were set to CT = 38. The reference/control group was set to 1 for all five experimental studies.

For the HDM and corn pollen studies, transcripts of several Cyp2j isoforms were below the limit of detection for all samples (CT > 38). In the figures, these data points are shown without error bars. Outliers were detected and removed using the Grubbs Outlier test (Grubbs, 1950). Significance was calculated by the Student’s t test. Multiple test comparisons are not reported because the primary focus of this study was the qPCR analysis of the seven Cyp2j subfamily members.

Results

Cyp2j TaqMan Primer/Probes and SYBR Green Primer Sets Specificity.

The mouse Cyp2j subfamily cDNAs were previously cloned in our laboratory (Ma et al., 1999; Qu et al., 2001; Ma et al., 2002; Graves et al., 2013). Each cDNA was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Life Technologies) or pBS-SK+ vector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). All seven of the mouse Cyp2j TaqMan primer/probe assays and the seven SYBR Green primer sets were specific for their intended mouse Cyp2j cDNA (Figs. 1–7; A and B). In addition, the Cyp2j TaqMan primer/probes and SYBR Green primer sets failed to amplify any of the 10 mouse Cyp2c cDNAs tested (data not shown). Cyp2c isoforms are a closely related gene subfamily with approximately 50% identity to the Cyp2j subfamily at the nucleotide level.

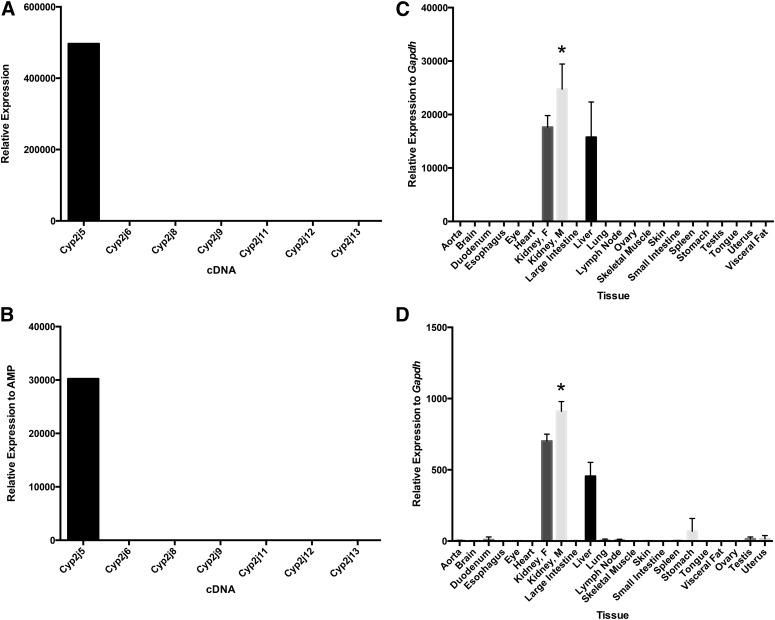

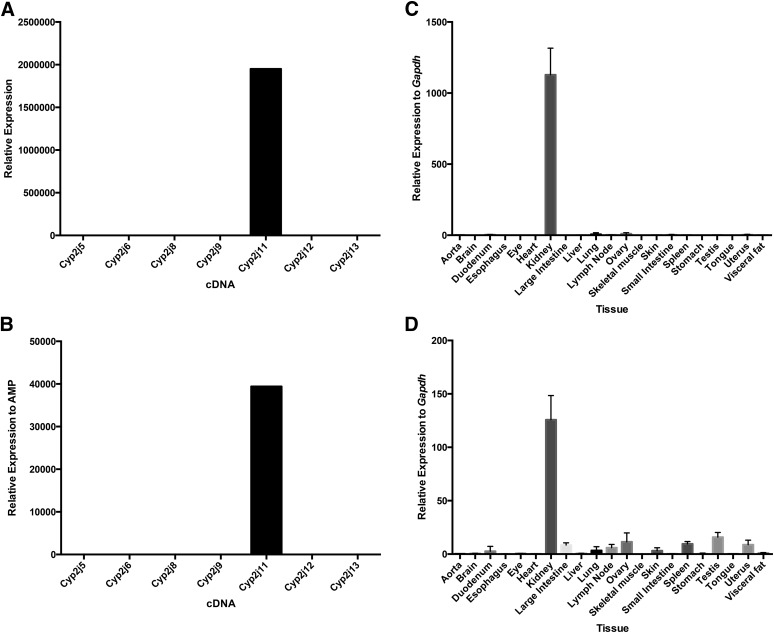

Fig. 1.

Specificity and tissue distribution of mouse Cyp2j5 using TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets. The Cyp2j5 TaqMan primer/probe (A) and the SYBR Green Cyp2j5 primer set (B) are specific for the Cyp2j5 cDNA. Both the Cyp2j5 TaqMan primer/probe (C) and SYBR Green primer set (D) show the highest expression of Cyp2j5 in male kidneys with lower expression in female kidneys and livers. Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 6 per group except for sex-specific tissues where n = 3 per group; *P < 0.05, male versus female kidney.

Fig. 7.

Specificity and tissue distribution of mouse Cyp2j13 using TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets. Both the Cyp2j13 TaqMan primer/probe (A) and the SYBR Green primer set (B) are specific for the Cyp2j13 cDNA. Expression was present only in male kidney using both the TaqMan primer/probe (C) and the SYBR Green primer set (D). Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 6 per group except for sex-specific tissues where n = 3 per group. *P < 0.05, male versus female kidney.

Tissue Distribution of Mouse Cyp2j mRNAs by qPCR.

Using both the TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets, Cyp2j5 was most abundant in male and female kidneys and in the liver (Fig. 1). The expression level of Cyp2j5 in the male kidney was significantly higher than in the female kidney and liver, measured using either qPCR method. This finding is in agreement with previously reported, nonquantitative RT-PCR results (Ma et al., 1999).

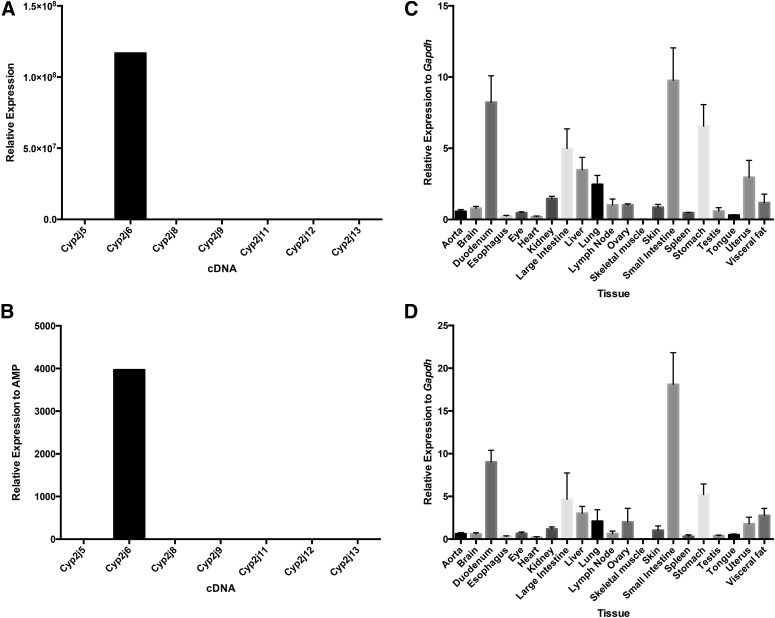

For Cyp2j6, the highest expression levels using both the TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer set were in the small intestine, in particular in the duodenum (Fig. 2). Cyp2j6 was also detected at low but detectable levels in the large intestine, stomach, liver, lung, ovary, uterus, skin, kidney, and visceral fat. This broad tissue distribution of Cyp2j6 was also observed previously by nonquantitative RT-PCR methods (Scarborough et al., 1999).

Fig. 2.

Specificity and tissue distribution of mouse Cyp2j6 using TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets. Both the Cyp2j6 TaqMan primer/probe (A) and SYBR Green primer set (B) are specific for the Cyp2j6 cDNA. Similar tissue distribution profiles were observed using both the TaqMan primer/probe (C) and SYBR Green primer set (D), with the highest expression in the small intestine, duodenum, stomach, and large intestine. Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 6 per group.

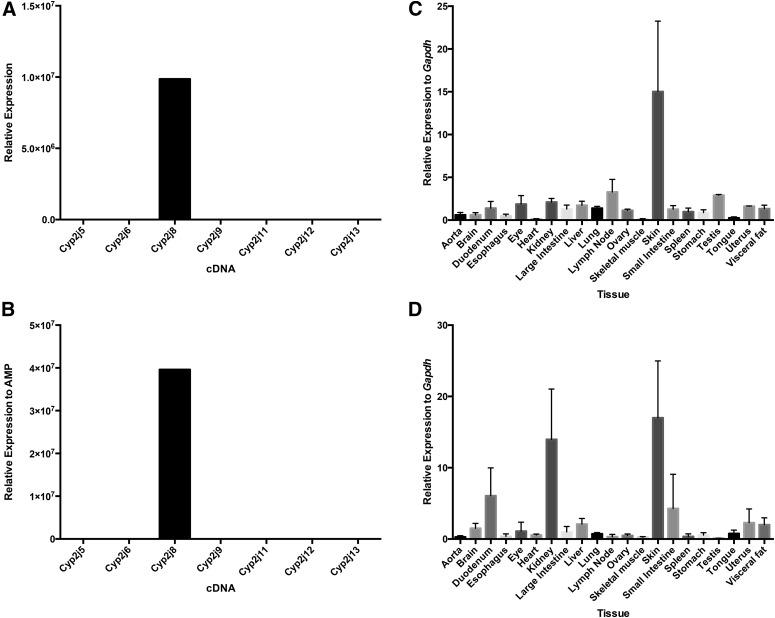

Examination of qPCR results from the Cyp2j8-specific TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer set revealed that Cyp2j8 expression was highest in skin and found at lower levels in a broad range of tissues including the liver, brain, and duodenum (Fig. 3). In addition, we observed abundant expression in the kidney only with the SYBR Green Cyp2j8 primer set. These findings are consistent with published results using nonquantitative RT-PCR methods (Graves et al., 2013), although skin was not included in the prior panel.

Fig. 3.

Specificity and tissue distribution of mouse Cyp2j8 using TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets. Both the Cyp2j8 TaqMan primer/probe (A) and SYBR Green primer set (B) are specific for Cyp2j8 cDNA. Expression was highest in the skin using both the TaqMan primer/probe (C) and the SYBR Green primer set (D). Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 6 per group.

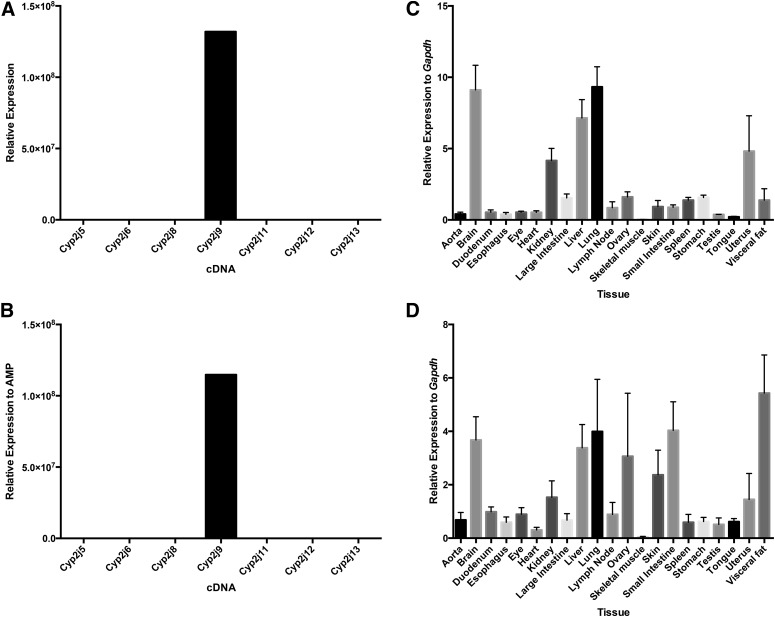

Cyp2j9 transcripts were detected in the brain, liver, and lung using either the TaqMan or SYBR Green qPCR methods (Fig. 4). Previous nonquantitative RT-PCR methods showed a similar pattern of expression in the brain and liver but not the lung (Qu et al., 2001). When using SYBR Green primers, high expression levels of Cyp2j9 were detected in the visceral fat, ovary, skin, and small intestine that were not detected by the TaqMan primer/probe. To address the apparent discrepancy between the two assays, we compared the SYBR Green dissociation curve for brain, liver, and lung with that of fat, ovary, and small intestine (Supplemental Fig. 4). The single observed peak with a nearly identical melting temperature is highly suggestive that the measured fluorescence in all six tissues is due to an amplicon derived from the Cyp2j9 transcript and not off-target amplification of unintended transcripts.

Fig. 4.

Specificity and tissue distribution of mouse Cyp2j9 using TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets. Both the Cyp2j9 TaqMan primer/probe (A) and SYBR Green primer set (B) are specific for the Cyp2j9 cDNA. The highest expression was in the brain, liver, and lung using both the TaqMan primer/probe (C) and the SYBR Green primer set (D). Abundant expression was also observed in the ovary, skin, small intestine, and visceral fat for the Cyp2j9 SYBR Green primer set. Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 6 per group.

A prominent Cyp2j11 transcript was detected in kidney samples using both TaqMan and SYBR Green qPCR methods (Fig. 5). Unlike Cyp2j5 and Cyp2j13, which have male-selective kidney expression, both male and female kidneys abundantly expressed Cyp2j11 transcripts. Previously published nonquantitative RT-PCR analysis detected abundant Cyp2j11 expression in the kidney and heart (Graves et al., 2013); however, robust expression was not observed in the heart with either qPCR method.

Fig. 5.

Specificity and tissue distribution of mouse Cyp2j11 using TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets. Both the Cyp2j11 TaqMan primer/probe (A) and SYBR Green primer set (B) are specific for the Cyp2j11 cDNA. Expression was highest in the kidney using both the TaqMan primer/probe (C) and the SYBR Green primer set (D). Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 6 per group.

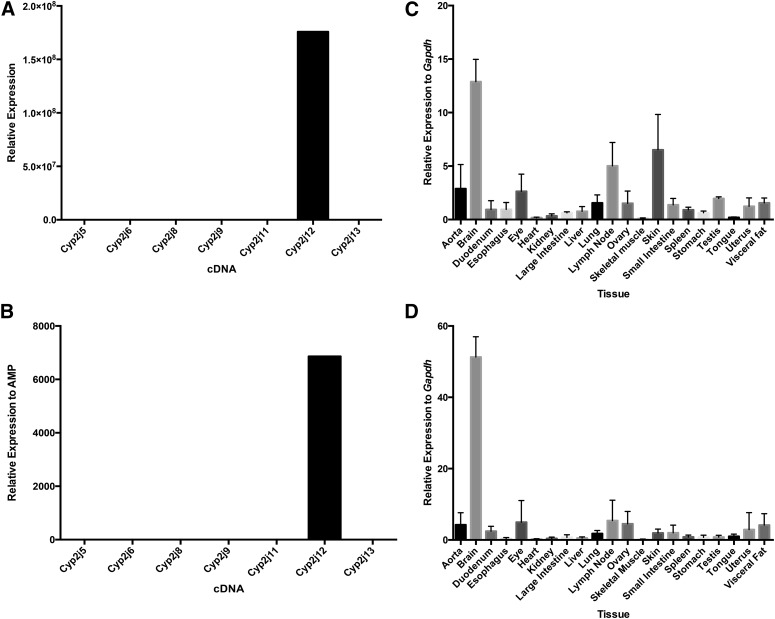

Prominent Cyp2j12 expression was detected in the brain with both the TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets (Fig. 6). Previously published nonquantitative RT-PCR methods also showed high transcript levels in the brain (Graves et al., 2013).

Fig. 6.

Specificity and tissue distribution of mouse Cyp2j12 using TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets. Both the Cyp2j12 TaqMan primer/probe (A) and SYBR Green primer set (B) are specific for the Cyp2j12 cDNA. The highest expression was in the brain using both the TaqMan primer/probe (C) and the SYBR Green primer set (D). Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 6 per group.

Cyp2j13 transcript expression is detected almost exclusively in male kidney by both the TaqMan primer/probe and SYBR Green primer sets (Fig. 7).

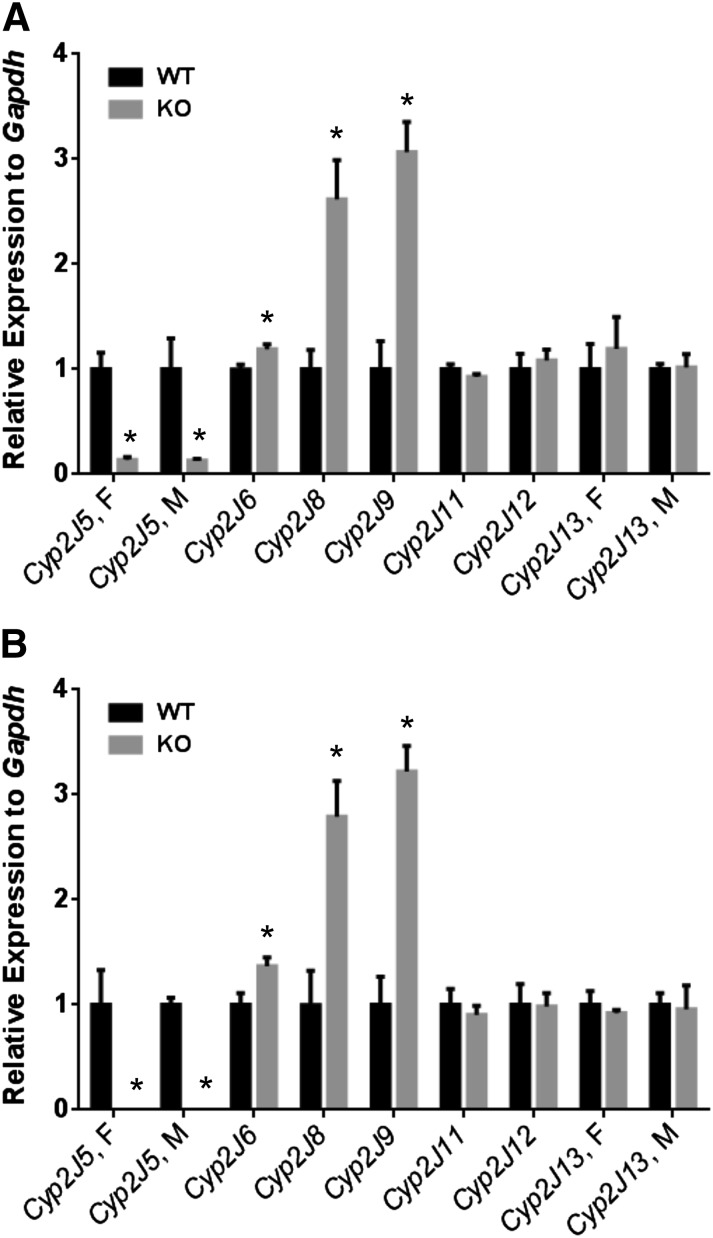

Expression of Mouse Cyp2j Isoforms in Kidneys of Cyp2j5 KO Mice.

Both TaqMan and SYBR Green qPCR were used to determine expression levels for the Cyp2j isoforms in Cyp2j5 KO and WT kidneys (Fig. 8). Consistent with previous data (Ma et al., 1999), Cyp2j5 transcript levels were below the level of detection (CT > 38) in CYP2J5 KO mice. Both qPCR methods showed that the expression levels of Cyp2j6, Cyp2j8, and Cyp2j9 in the kidney were significantly increased in Cyp2j5 KO mice relative to WT controls. In contrast, there were no compensatory changes in Cyp2j11 or Cyp2j13 expression in Cyp2j5 KO mice.

Fig. 8.

Detection of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms in Cyp2j5 WT and KO kidney. Both the Cyp2j5 TaqMan primer/probe (A) and the SYBR Green primer set (B) revealed significantly lower Cyp2j5 expression in the KO kidney. In contrast, Cyp2j6, Cyp2j8, and Cyp2j9 were increased in the Cyp2j5 KO kidney relative to WT using both the TaqMan primer/probe (A) and the SYBR Green primer sets (B). Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05 Cyp2j5 KO versus WT.

Expression of the Cyp2j isoforms was also examined in Cyp2j5 KO and WT livers (Supplemental Fig. 5). As in the kidney, Cyp2j5 disruption leads to compensatory up-regulation of Cyp2j8 and Cyp2j9. Cyp2j6 expression was slightly reduced in livers from Cyp2j5 KO mice relative to WT. This is in contrast to a modest induction of Cyp2j6 in kidneys from Cyp2j5 KO mice.

Expression of Mouse Cyp2j Isoforms in Lungs of Influenza A-Treated Mice.

Treatment of mice with 200 plaque-forming units of influenza A is typically lethal beyond 4 days; therefore, mice were euthanized on day 4 to assess Cyp2j isoform expression. Relative expression of Cyp2j isoforms in mice treated with influenza A was calculated separately for female and male mice due to known sex differences in response to infection (Carey et al., 2007; Larcombe et al., 2011).

Compared with saline-treated controls, influenza A–treated lungs showed a significant decrease in expression of Cyp2j9 (Fig. 9). This result was consistent using both qPCR methods and was similar in both males and females. In female mice there was also a trend toward reduction in levels of Cyp2j5 (P = 0.05), Cyp2j6 (P = 0.06), Cyp2j8 (P = 0.07), and Cyp2j11 (P = 0.07) isoforms with the TaqMan primer/probes. In contrast, with the SYBR Green primers only Cyp2j6 tended to be reduced in influenza A–treated females relative to saline-treated controls (P = 0.05).

Fig. 9.

Detection of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms in lungs of mice treated with influenza A virus. Similar expression profiles were observed in female mice with the use of both the Cyp2j TaqMan primer probes (A) and SYBR Green primer sets (B). For male mice the Cyp2j TaqMan primer/probe (C) and SYBR Green primer sets (D) also gave similar results. Cyp2j9 was significantly reduced in the influenza A–treated mice for both female and male mice with both qPCR methods. Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05, compared with saline control.

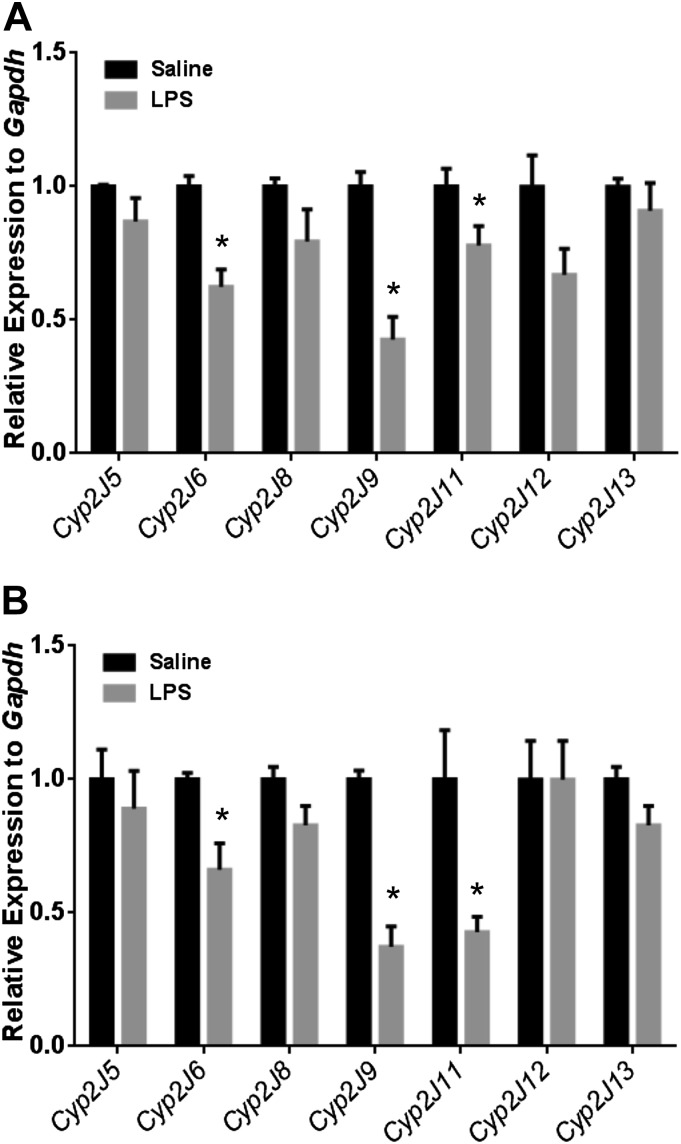

Expression of Mouse Cyp2j Isoforms in Lungs of LPS-Treated Mice.

Cyp2j isoform expression was measured in mouse lungs 4 hours after LPS or saline treatment. Compared with saline-treated controls, LPS treated mice showed significantly reduced lung expression of Cyp2j6, Cyp2j9, and Cyp2j11 (Fig. 10). There were no differences in expression of the other Cyp2j isoforms. These findings were consistent in both TaqMan and SYBR Green assays.

Fig. 10.

Detection of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms in lungs of LPS-treated mice. Similar profiles of expression were observed using the Cyp2j TaqMan primer/probes (A) and the SYBR Green primer sets (B). Cyp2j6, Cyp2j9, and Cyp2j11 were decreased in the LPS-treated lung. Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 6 per group; *P < 0.05, compared with saline control.

Expression of Mouse Cyp2j Isoforms in Lungs of HDM-Treated Mice.

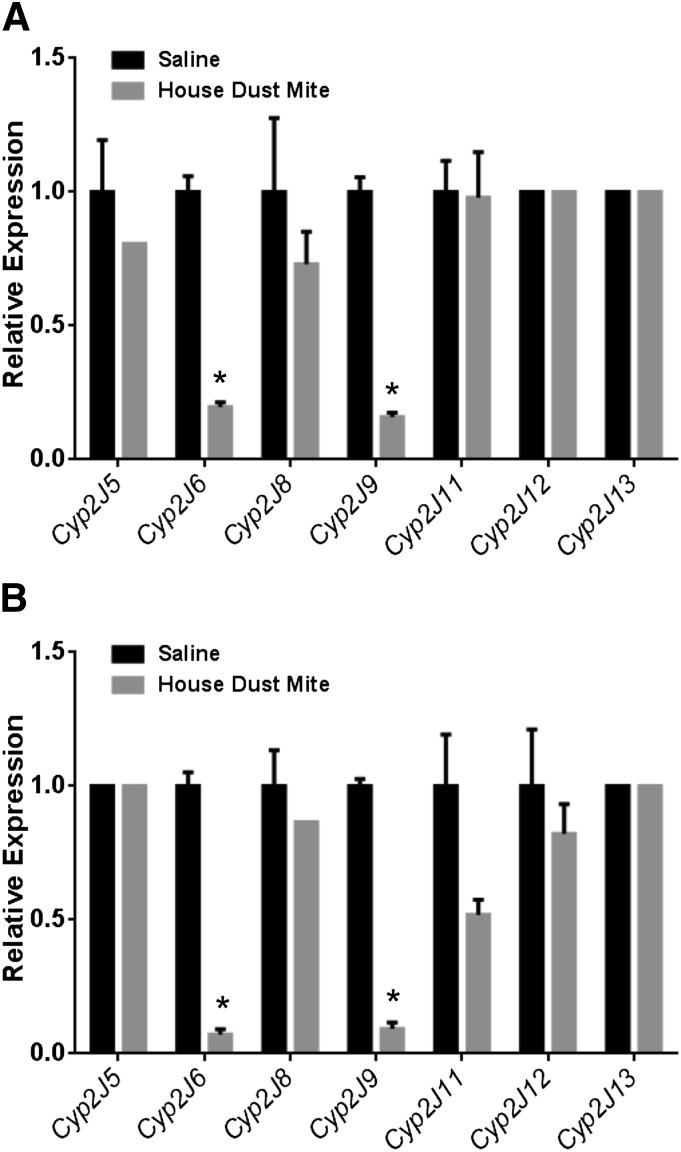

To assess Cyp2j isoform expression in a model of allergic asthma, mice were sensitized and exposed to HDM in an 18-day protocol as described in Materials and Methods. Both the TaqMan primer/probes and SYBR Green primer sets detected significantly reduced expression of Cyp2j6 and Cyp2j9 in the lungs of HDM-treated mice relative to saline-treated controls (Fig. 11). In addition, when using the SYBR Green primer set, there was a small reduction in Cyp2j11 expression in the HDM-treated lungs relative to saline-treated controls. None of the other isoforms exhibited differential expression patterns with either qPCR method.

Fig. 11.

Detection of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms in lungs from HDM-treated mice. Both the TaqMan primer/probes (A) and SYBR Green primer sets (B) showed decreased expression of Cyp2j6 and Cyp2j9 in the HDM-treated lungs. Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 6 per group for HDM-treated lungs and n = 5 per group for saline-treated lungs; *P < 0.05, compared with saline controls.

Expression of Mouse Cyp2j Isoforms in Lungs after Acute and Chronic Exposure to Corn Pollen.

Expression of Cyp2j isoforms was also assessed 24 hours after a single dose or 24 hours after the final consecutive daily dose of corn pollen. After acute exposure to corn pollen, Cyp2j6 and Cyp2j9 isoforms were significantly reduced compared with saline-treated controls (Fig. 12, A and B). Chronic corn pollen exposure also strongly reduced Cyp2j6 and Cyp2j9 transcript levels (Fig. 12, C and D). There was a smaller but statistically significant reduction in Cyp2j8 expression detected with the TaqMan primer/probe set (Fig. 12C). Because the corn pollen studies were conducted using BALB/C rather than C57BL/6 mice, we verified that the tissue expression profiles for the mouse Cyp2j isoforms were similar in both C57BL/6 and BALB/C mice. Examples of the BALB/C tissue profile expression for Cyp2j6 and Cyp2j9 are shown in Supplemental Fig. 6.

Fig. 12.

Detection of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms in lungs from corn pollen–treated mice. Using both qPCR methods, in acute (A and B) and chronic (C and D) exposure models, there was a significant decrease in expression of Cyp2j6 and Cyp2j9. With chronic exposure to corn pollen, the TaqMan primer/probe (C), also showed decreased expression of Cyp2j8. Data shown are mean ± S.E., n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05, compared with saline controls.

Discussion

Cytochromes P450 is a large gene superfamily of ubiquitous hemoproteins that have physiologically relevant hepatic and extrahepatic functions (Wu et al., 1996; Zou et al., 1996; Campbell and Harder, 1999; Node et al., 2001). Members of the CYP2J subfamily metabolize AA and linoleic acid into bioactive lipids (Ma et al., 1999; Qu et al., 2001; Ma et al., 2002; Graves et al., 2013). Identifying tissue expression patterns of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms and quantifying their expression levels after various treatments is important for determining the physiologic role of these enzymes. The tissue distribution of the seven members of the mouse Cyp2j subfamily had previously been determined by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis (Ma et al., 1999; Qu et al., 2001; Ma et al., 2002; Graves et al., 2013). In a recent study, reverse-transcription, multiplex, ligation-dependent probe amplification was used to measure mouse Cyp2j gene expression (Zhou et al., 2013); however, qPCR is a more widely available quantitative assay and provides an accurate expression profile across tissues.

In this report, the TaqMan and SYBR Green qPCR showed excellent specificity toward each of the mouse Cyp2j subfamily members. Our results provide a catalog of Cyp2j tissue expression that is in general agreement with previously published data. Moreover, we used these two qPCR methods to document compensatory Cyp2j transcript expression in Cyp2j5 KO mouse kidneys. We also quantified expression of Cyp2j genes in experimental models of lung inflammation induced by influenza A, LPS, HDM allergen, and corn pollen. The efficacy of the two qPCR methods to determine differences in expression of the various Cyp2j isoforms was comparable.

The Cyp2j TaqMan primer/probes and SYBR Green primer sets are highly specific to their respective Cyp2j isoform. The tissue expression profiles for all seven of the Cyp2j subfamily members were similar using both TaqMan and SYBR Green qPCR methods. Indeed, each Cyp2j tissue expression profile was consistent with previously reported nonquantitative RT-PCR results (Ma et al., 1999; Qu et al., 2001; Ma et al., 2002; Graves et al., 2013) with a few notable exceptions. For example, nonquantitative RT-PCR had detected Cyp2j8 in the mouse kidney and heart, whereas both qPCR methods confirmed abundant expression in the kidney but not the heart. In addition, we previously reported that Cyp2j8 was abundantly expressed in the brain (Graves et al., 2013); however, qPCR revealed the highest expression in the skin, a tissue that was not included in the previous analysis.

CYP2J metabolites, the EETs, act as cerebral vasodilators and are neuroprotective (Zhang et al., 2008). The Cyp2j9 and Cyp2j12 transcripts are present in the brain by both qPCR methods. These results are in agreement with our prior nonquantitative RT-PCR results (Qu et al., 2001; Graves et al., 2013). Cyp2j8 was previously reported by nonquantitative RT-PCR to be highly expressed in the brain (Graves et al., 2013); however, only low levels of Cyp2j8 was detected in the brain using either of the qPCR methods in our current study. Notably, the SYBR Green Cyp2j8 primer set used in this study is different than the ones used in the previous nonquantitative RT-PCR. Confirmation of the low expression levels of Cyp2j8 in the brain by the TaqMan primer/probe set suggests that Cyp2j8 is not highly expressed in the brain.

Cytochrome P450 enzymes located in the gastrointestinal tract may play a role in the biotransformation of dietary nutrients as well as xenochemicals (Kaminsky and Fasco, 1991). In the current study, Cyp2j6 was shown by both TaqMan and SYBR Green qPCR methods to have the highest expression in the small intestine, duodenum, stomach, and large intestine. This is in agreement with the published data on the expression of Cyp2j6 in the small intestine as measured by nonquantitative RT-PCR (Scarborough et al., 1999; Ma et al., 2002). It is noteworthy that in previous studies the stomach and large intestine were not included in the tissue panel used for nonquantitative RT-PCR (Graves et al., 2013).

CYP2J metabolites, the EETs, play an important role in the regulation of blood pressure in both rodents and humans (Wu et al., 1996; Holla et al., 1999; Ma et al., 1999; Oyekan et al., 1999). Indeed, Cyp2j5 KO mice develop spontaneous hypertension (Athirakul et al., 2008). Moreover, Cyp2j expression in the kidney is localized to the site of the nephron where EETs regulate the hormones that control blood pressure (Ma et al., 1999). Results from both qPCR methods indicated that all of the mouse Cyp2j subfamily members except Cyp2j12 were expressed in the kidney. In fact, Cyp2j5, Cyp2j11, and Cyp2j13 are most abundantly expressed in the kidney. Cyp2j11 has comparable expression in both male and female kidneys, Cyp2j5 has higher expression in male compared with female kidneys, and Cyp2j13 is almost exclusively expressed in male kidneys.

Cyp2j6, Cyp2j8, and Cyp2j9 also have detectable expression in the kidney by both qPCR methods. Regulation of kidney Cyp2js has not been extensively studied. In this regard, we found that there was compensatory upregulation of Cyp2j6, Cyp2j8, and Cyp2j9 in the kidneys of Cyp2j5 KO mice relative to WT controls. Interestingly, Cyp2j5 KO mice have increased blood pressure despite normal renal EET biosynthesis. Therefore, it is possible that either Cyp2j5 does not significantly contribute to renal EET biosynthesis or alternatively that up-regulation of Cyp2j6, Cyp2j8, and Cyp2j9 compensates for the loss of Cyp2j5 and normalizes renal EET levels. Notably, there is no difference in expression of Cyp2j11 in Cyp2j5 KO versus WT kidneys using either qPCR method, despite the fact that both isoforms are abundantly expressed in renal proximal tubules (Ma et al., 1999; Graves et al., 2013).

Further studies will be needed to determine whether there is redundancy of function between the mouse renal Cyp2j isoforms, and whether this contributes to the hypertensive phenotype in Cyp2j5 KO mice. In liver tissues, Cyp2j5 disruption also induced compensatory changes in Cyp2j8 and Cyp2j9 expression; however, although Cyp2j5 disruption induced Cyp2j6 expression in the kidney, it suppressed Cyp2j6 expression in the liver. Thus, compensatory changes in Cyp2j6 expression in Cyp2j5 KO mice appear to occur in a tissue-specific fashion.

EETs have been shown to possess significant anti-inflammatory properties (Campbell et al., 1996; Node et al., 1999; Larsen et al., 2006). Inflammation is known to affect the expression and metabolic capacity of hepatic and extrahepatic P450 enzymes (Morgan, 2001; Theken et al., 2011). P450 expression is usually suppressed in inflammatory states, but it may also be induced or unaffected (Morgan, 1997). In the current study, we examined expression of the Cyp2j isoforms in four lung inflammatory models. Influenza A infection induces inflammation in the lungs of mice (Virelizier et al., 1979; Dawson et al., 2000). LPS is part of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and induces airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness (Zeldin et al., 2001). HDM allergen is a well-studied inducer of allergic airway inflammation (Gandhi et al., 2013). In addition, both acute and chronic corn pollen exposure induces allergic airway inflammation (Card, J.W., et al., unpublished data).

The two qPCR methods revealed similar patterns of suppressed Cyp2j expression in the lung during inflammation in these inflammatory models. As EETs are anti-inflammatory, the reduction of CYP2J epoxygenases during inflammation may serve to amplify inflammatory signals so that organisms may mount an efficient defense against pathogens. Influenza A–infected mice showed a modest reduction of most Cyp2j isoforms; only the reduction in Cyp2j9 was statistically significant.

Sex differences in immune responses are well established (Carey et al., 2007). The reduction of Cyp2j9 expression was similar in males and females; however, we observed a trend for reduction of several other Cyp2j isoforms in female mice (P = 0.05–0.1). Interestingly, no significant change in any of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms was observed using a human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) model (Supplemental Fig. 7). This suggests that changes in the expression of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms may be virus specific.

Acute LPS treatment suppressed pulmonary expression of Cyp2j6, Cyp2j8, and Cyp2j9. This is very similar to previous reports that found no change in Cyp2j5 but found reduced Cyp2j9 expression after LPS exposure (Theken et al., 2011). We found that Cyp2j5, Cyp2j11, Cyp2j12, and Cyp2j13 are expressed at very low levels in the lung, so a lack of inflammatory suppression of these genes is not surprising. While the bacterial LPS model suppressed Cyp2j6, Cyp2j8, and Cyp2j9 expression, the influenza A virus only significantly reduced expression of Cyp2j9.

Different models of infection are known to affect different P450 enzymes in hepatic and extrahepatic tissues (Morgan, 1997). Further studies will be needed to determine the specific transcription factors responsible for suppression of the individual mouse Cyp2j isoforms in each of these models. The induction of allergy to HDM and the acute and chronic exposure of corn pollen yielded similar responses; both allergens induced a strong suppression of Cyp2j6 and Cyp2j9 expression in the lung. The other mouse Cyp2js are expressed at lower levels in the lung and are not significantly altered in these models. To our knowledge, the effect of allergens on Cyp2j expression has not previously been reported. Whether suppression of the mouse Cyp2js is a factor in allergic lung response remains to be determined.

In summary, we compared the tissue expression profiles of the seven mouse Cyp2j isoforms using two different qPCR methods: one method using the TaqMan primer/probe assay and the other using SYBR Green primer sets that we developed in our laboratory. Overall, similar expression profiles were observed for all seven isoforms with the two qPCR methods. We found compensatory up-regulation of several mouse Cyp2j isoforms in the kidneys of Cyp2j5 KO mice. In addition, the levels of several of the mouse Cyp2j isoforms were reduced in models of pulmonary inflammation. The SYBR Green qPCR primer sets we developed may be an accurate and less expensive alternative to TaqMan commercial primer/probe assays for the quantitative detection of expression of mouse Cyp2j subfamily members under normal and pathologic conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jacqui Marzec and Dr. Hye-Youn Cho for the RSV RNAs, and Lois Wyrick for graphic arts assistance.

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- EET

epoxyeicosatrienoic acid

- HDM

house dust mite

- KO

knockout

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- P450

cytochrome P450

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RT-PCR

reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

- WT

wild type

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Graves, Gruzdev, Edin, Zeldin.

Conducted experiments: Graves.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Bradbury, DeGraff, Li.

Performed data analysis: Graves, Gruzdev, Zeldin.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Graves, Gruzdev, Hoopes, House, Edin, Zeldin.

Footnotes

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Z01 ES025034].

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Athirakul K, Bradbury JA, Graves JP, DeGraff LM, Ma J, Zhao Y, Couse JF, Quigley R, Harder DR, Zhao X, et al. (2008) Increased blood pressure in mice lacking cytochrome P450 2J5. FASEB J 22:4096–4108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WB, Gebremedhin D, Pratt PF, Harder DR. (1996) Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res 78:415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WB, Harder DR. (1999) Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors and vascular cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in the regulation of tone. Circ Res 84:484–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Harris RC. (2000) Cytochrome P450 and arachidonic acid bioactivation. Molecular and functional properties of the arachidonate monooxygenase. J Lipid Res 41:163–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MA, Card JW, Voltz JW, Germolec DR, Korach KS, Zeldin DC. (2007) The impact of sex and sex hormones on lung physiology and disease: lessons from animal studies. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293:L272–L278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TC, Beck MA, Kuziel WA, Henderson F, Maeda N. (2000) Contrasting effects of CCR5 and CCR2 deficiency in the pulmonary inflammatory response to influenza A virus. Am J Pathol 156:1951–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi VD, Davidson C, Asaduzzaman M, Nahirney D, Vliagoftis H. (2013) House dust mite interactions with airway epithelium: role in allergic airway inflammation. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 13:262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves JP, Edin ML, Bradbury JA, Gruzdev A, Cheng J, Lih FB, Masinde TA, Qu W, Clayton NP, Morrison JP, et al. (2013) Characterization of four new mouse cytochrome P450 enzymes of the CYP2J subfamily. Drug Metab Dispos 41:763–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs FE. (1950) Sample criteria for testing outlying observations. Ann Math Stat 21:27–58. [Google Scholar]

- Heid CA, Stevens J, Livak KJ, Williams PM. (1996) Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res 6:986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holla VR, Makita K, Zaphiropoulos PG, Capdevila JH. (1999) The kidney cytochrome P-450 2C23 arachidonic acid epoxygenase is upregulated during dietary salt loading. J Clin Invest 104:751–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky LS, Fasco MJ. (1991) Small intestinal cytochromes P450. Crit Rev Toxicol 21:407–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroetz DL, Zeldin DC. (2002) Cytochrome P450 pathways of arachidonic acid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol 13:273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larcombe AN, Foong RE, Bozanich EM, Berry LJ, Garratt LW, Gualano RC, Jones JE, Dousha LF, Zosky GR, Sly PD. (2011) Sexual dimorphism in lung function responses to acute influenza A infection. Influenza Other Respi Viruses 5:334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen BT, Miura H, Hatoum OA, Campbell WB, Hammock BD, Zeldin DC, Falck JR, Gutterman DD. (2006) Epoxyeicosatrienoic and dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids dilate human coronary arterioles via BK(Ca) channels: implications for soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290:H491–H499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Bradbury JA, King L, Maronpot R, Davis LS, Breyer MD, Zeldin DC. (2002) Molecular cloning and characterization of mouse CYP2J6, an unstable cytochrome P450 isoform. Biochem Pharmacol 64:1447–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Qu W, Scarborough PE, Tomer KB, Moomaw CR, Maronpot R, Davis LS, Breyer MD, Zeldin DC. (1999) Molecular cloning, enzymatic characterization, developmental expression, and cellular localization of a mouse cytochrome P450 highly expressed in kidney. J Biol Chem 274:17777–17788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan ET. (1997) Regulation of cytochromes P450 during inflammation and infection. Drug Metab Rev 29:1129–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan ET. (2001) Regulation of cytochrome p450 by inflammatory mediators: why and how? Drug Metab Dispos 29:207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Russell DW. (2002) Clinical importance of the cytochromes P450. Lancet 360:1155–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DR, Koymans L, Kamataki T, Stegeman JJ, Feyereisen R, Waxman DJ, Waterman MR, Gotoh O, Coon MJ, Estabrook RW, et al. (1996) P450 superfamily: update on new sequences, gene mapping, accession numbers and nomenclature. Pharmacogenetics 6:1–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Node K, Huo Y, Ruan X, Yang B, Spiecker M, Ley K, Zeldin DC, Liao JK. (1999) Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science 285:1276–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Node K, Ruan XL, Dai J, Yang SX, Graham L, Zeldin DC, Liao JK. (2001) Activation of Galpha s mediates induction of tissue-type plasminogen activator gene transcription by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. J Biol Chem 276:15983–15989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyekan AO, Youseff T, Fulton D, Quilley J, McGiff JC. (1999) Renal cytochrome P450 omega-hydroxylase and epoxygenase activity are differentially modified by nitric oxide and sodium chloride. J Clin Invest 104:1131–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponchel F, Toomes C, Bransfield K, Leong FT, Douglas SH, Field SL, Bell SM, Combaret V, Puisieux A, Mighell AJ, et al. (2003) Real-time PCR based on SYBR-Green I fluorescence: an alternative to the TaqMan assay for a relative quantification of gene rearrangements, gene amplifications and micro gene deletions. BMC Biotechnol 3:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu W, Bradbury JA, Tsao CC, Maronpot R, Harry GJ, Parker CE, Davis LS, Breyer MD, Waalkes MP, Falck JR, et al. (2001) Cytochrome P450 CYP2J9, a new mouse arachidonic acid omega-1 hydroxylase predominantly expressed in brain. J Biol Chem 276:25467–25479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough PE, Ma J, Qu W, Zeldin DC. (1999) P450 subfamily CYP2J and their role in the bioactivation of arachidonic acid in extrahepatic tissues. Drug Metab Rev 31:205–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seubert J, Yang B, Bradbury JA, Graves J, Degraff LM, Gabel S, Gooch R, Foley J, Newman J, Mao L, et al. (2004) Enhanced postischemic functional recovery in CYP2J2 transgenic hearts involves mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels and p42/p44 MAPK pathway. Circ Res 95:506–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seubert JM, Sinal CJ, Graves J, DeGraff LM, Bradbury JA, Lee CR, Goralski K, Carey MA, Luria A, Newman JW, et al. (2006) Role of soluble epoxide hydrolase in postischemic recovery of heart contractile function. Circ Res 99:442–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theken KN, Deng Y, Kannon MA, Miller TM, Poloyac SM, Lee CR. (2011) Activation of the acute inflammatory response alters cytochrome P450 expression and eicosanoid metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos 39:22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virelizier JL, Allison AC, Schild GC. (1979) Immune responses to influenza virus in the mouse, and their role in control of the infection. Br Med Bull 35:65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wei X, Xiao X, Hui R, Card JW, Carey MA, Wang DW, Zeldin DC. (2005) Arachidonic acid epoxygenase metabolites stimulate endothelial cell growth and angiogenesis via mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314:522–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Moomaw CR, Tomer KB, Falck JR, Zeldin DC. (1996) Molecular cloning and expression of CYP2J2, a human cytochrome P450 arachidonic acid epoxygenase highly expressed in heart. J Biol Chem 271:3460–3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldin DC, Wohlford-Lenane C, Chulada P, Bradbury JA, Scarborough PE, Roggli V, Langenbach R, Schwartz DA. (2001) Airway inflammation and responsiveness in prostaglandin H synthase-deficient mice exposed to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 25:457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Otsuka T, Sugo N, Ardeshiri A, Alhadid YK, Iliff JJ, DeBarber AE, Koop DR, Alkayed NJ. (2008) Soluble epoxide hydrolase gene deletion is protective against experimental cerebral ischemia. Stroke 39:2073–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou GL, Beloiartsev A, Yu B, Baron DM, Zhou W, Niedra R, Lu N, Tainsh LT, Zapol WM, Seed B, et al. (2013) Deletion of the murine cytochrome P450 Cyp2j locus by fused BAC-mediated recombination identifies a role for Cyp2j in the pulmonary vascular response to hypoxia. PLoS Genet 9:e1003950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou AP, Drummond HA, Roman RJ. (1996) Role of 20-HETE in elevating loop chloride reabsorption in Dahl SS/Jr rats. Hypertension 27:631–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.