NEPTUNE encourages collaborations for integrative biomedical research across disciplines, sub-specialties, institutions and geographies. Working together, researchers access, manipulate, transform, validate, and share data and knowledge for novel insights into molecular mechanisms of renal disease. With combined expertise they discover and confirm what none alone could have done. Yet collaborative research has many challenges. Some challenges have been closely examined by team science researchers, and they are mainly related to interpersonal and organizational dynamics for collaborative readiness [1]. Other challenges, however, are not so well researched, especially the challenge of achieving seamless flows of technology-enabled discovery-driven analyses within and across collaborating groups. A seamless flow of analysis calls for aligning collaborators’ research practices and evolving analytic reasoning to the technologies that best support them [2]. Supportive technologies are wide-ranging and may include databases and data management tools, security protocols, high throughput instrumentation, diverse software applications, algorithms, data transfer protocols, ontologies, and web resources and services. These technologies together with equipment, services, computational resources and domain tools make up a research infrastructure. In one survey, team scientists ranked adequate and appropriate resources and infrastructure as a top ten need for productive research [3].

Importantly, a research infrastructure involves more than the availability of enabling technologies and services. It requires combinations and configurations of them that will accomplish the “ultimate goal [of] ... allow[ing] scientists to enhance their collaborative problem solving capabilities through the improved and integrated usage of resources and tools” [4: 39]. A research infrastructure implements requirements for research capabilities. We define research capabilities as competencies for leveraging human, organizational and technical resources and services for purposes defined by the goals of a research project. Translational researchers note that when resources and infrastructures are insufficiently matched and configured to their needs and purposes, their research progress tends to be delayed. Moreover, they often have to re-invent the wheel in each project in terms of logistics, data exchanges, harmonization, databases, and interfaces. This fitness-to-purpose hinges on aligning technologies with analysts’ reasoning and behaviors, which, in turn, requires a good understanding of researchers’ goal-driven workflows and the challenges they encounter in them for their analytic needs [4 - 6].

In this article, we seek to advance this understanding. We describe a hypothetical workflow for integrative renal disease research. For each phase of the workflow we describe associated challenges. In practice, some challenges may recur across phases but for purposes of analysis we tie them to the phase in which they are most prominent. For the challenges, we propose technological supports and, at times, complementary organizational supports that may enhance researchers’ capabilities to address them. We categorize these supports by the type of research infrastructure requirement they connote. We strive to frame supports and categories in terms that will resonate with technology and organizational stakeholders. Toward this end, we adapt the language used in well-established capability maturity models and frameworks [5; 7-8]. Capability maturity models and frameworks address processes and resources that organizations and information technology units need to provide to meet business requirements.

Our adaptive uses of capability maturity models’ terms and categories for collaborative research infrastructures are distinct. To our knowledge little if any research centers – as we do – on the perspective of collaborating researchers’ flow of integrative biomedical analyses to identify unified sets of support for this research. From this perspective, we uncover combinations of technologies and organizational processes that need to be well-integrated to mitigate challenges that renal disease researchers may encounter in their systems-level analytic workflows. As a caveat, we do not provide “how to advice” - e.g. specific tool recommendations or configuration designs for solutions.

Our framing is preliminary and currently ongoing. By applying it here, we hope to help collaborating renal disease researchers recognize various connections between their workflows, technological challenges, necessary supports and categories of support in the research infrastructure. With this awareness, collaborating researchers may be better able to pre-emptively plan for and address these challenges. As neuroscience researchers have found in an outcome likely relevant to renal disease, “the growing importance of a complex, interoperable IT-based research infrastructure is underestimated in many research designs and could be optimized” [9: 6]. With this awareness researchers also may be better able to articulate and explain their research requirements to information technology (IT) units and together negotiate services and resources that enable collaborative research.

Overview: Research Workflow and Challenges

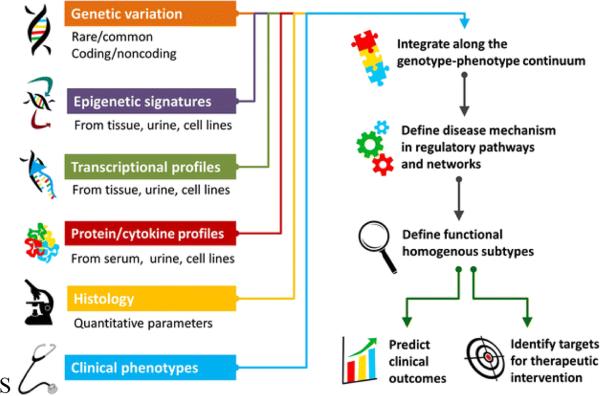

To construct the hypothetical workflow we synthesized studies from the research literature related to team science, computer-supported collaborative work, and analytical and visual analytic workflows in –omics inquiries [1- 3; 10-21]. We combined this synthesis with our own prior research on team science workflows and collaborations [22-27]. The workflow is generalized based on common patterns found in the research literature. Inescapably, workflows for systems-level renal disease research are idiosyncratic but certain phases, analytical purposes and practices are fairly common across cases [14]. For example, collaborating renal disease researchers often modularize their flows of analysis by structuring them into phases and by having specialists at specific biological scales conduct their parts of the analyses and then share them [24; 28]. The multiple scales that may come together are illustrated in Figure 1 [28-29].

Figure 1.

Multiple biological scales feeding into integrative renal disease research (courtesy of [29]).

Given the constraints of this article the scope of the sample workflow and associated challenges covers only collaborative analyses that concentrate on genetic variations, gene expression and clinical phenotypes. These analyses involve cross-disciplinary collaborations with biostatisticians and interactions with external members of the renal disease research network who specialize in histopathology and protein profiling. It also involves, at times, specialists within the institutional IT unit for obtaining necessary support. Other articles describe renal disease research workflows for levels of biology that are outside the scope of this essay [30]. In the workflow here investigators study large volumes of high quality data and ask such research questions as the following:

What genes and potentially novel pathways drive differences between patients with and without a risk haplotype?

What phenotypic traits and progression patterns of disease are correlated with genes found in animal models to affect Chronic Kidney Disease?

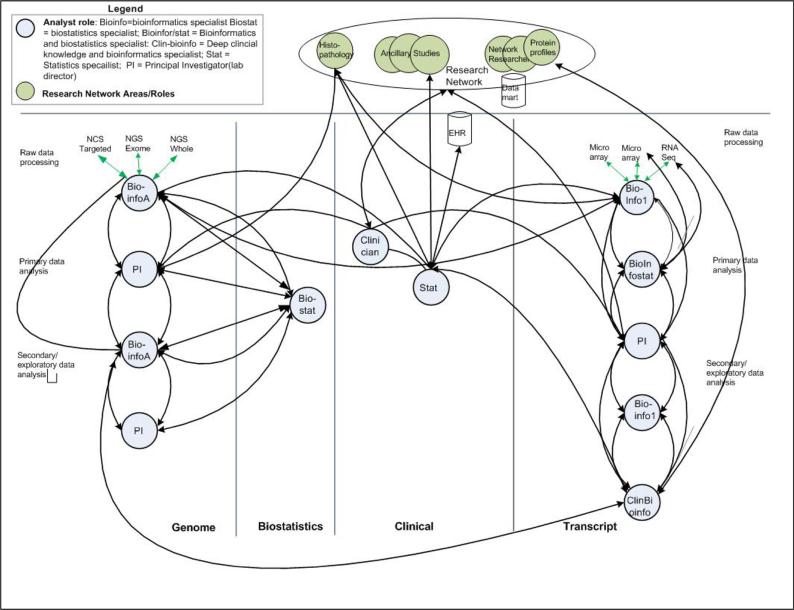

To address such questions collaborating researchers go through four phases: Raw data processing, primary analysis, integration and secondary analysis. We describe flows of analysis for each phase, highlight phase-specific challenges, and propose supports for addressing the challenges. Figure 2 represents a high level view of phase-specific analytic interactions among collaborators in genomics, transcriptomics, and biostatistics for clinical data. Interactions with a renal disease research network are included, as well.

Figure 2. Collaborative analyses within and across laboratories (bottom labels) and external network members.

The diagram shows the vertical flows of collaborative’ interactions in various sub-specialties and interactions across groups. The flows are structured by workflow phases (labeled as “rows”): raw data processing, primary analysis and secondary analysis. Circles represent collaborating researchers (abbreviations are defined in the Legend). Green circles represent members of the research network. Arrows signify collaborative interactions.

For this workflow collaborating researchers typically have many research capabilities in place for their investigations. For example, they have domain expertise, regularly used tools, some crucial processes in technical infrastructures and services, methodological know-how, and a good deal of support from organizational structures. Nonetheless challenges persist. They persist because it is a hard problem to align technologies to the flows of collaborating researchers’ integrative biomedical research. Complex collaborative flows of analysis require complex configurations of support.

The workflow suggests six challenges associated with collaborative analysis and sharing. They are: capacity for high volume data storage, processing and transfer; management of differently formatted data and/or files, data/file discoverability, integration and Identifier mapping; metadata; and unified tools for exploratory, ill-structured analysis. We describe challenges according to the phase in which collaborators frequently encounter them. We detail supports that may augment researchers’ capabilities to deal with them; and we tie supports to the relevant class of research infrastructure requirements

Raw data processing phase: Workflow, challenges and proposed support

Workflow description

For genomics data, collaborators conduct several types of next generation sequencing (NGS), e.g. exome sequencing, whole genome sequencing, and targeted sequencing. Researchers receive output of raw reads in FASTQ format but files may be formatted differently if they come from different instruments (e.g. Sanger vs Illumina). NGS processing time varies but two weeks is not an unusual length of time. For gene expression data, a different set of collaborators process microarray output files and RNA-Seq files. The processing of microarray data is done in a well-structured pipeline of procedures, often automated through workflow software (e.g. GenePattern or Taverna). In many laboratories, RNA-Seq processing is not yet similarly formalized. In genomics and transcriptomics, respectively, the researchers apply their expertise in renal disease, bioinformatics and computer science to reformat, as needed, and to determine the best analyses and complementary techniques to run for the research questions that the cross-disciplinary team is tackling. Choices of methods for normalizing, for example, affect later data interpretations.

Challenge. Capacity for high volume data storage, processing and transfer

High throughput techniques require high capacity equipment, special configurations of computing environments, and high speed networks with reliable protocols for data transfer. For the NGS runs and data transfer in the workflow, researchers typically depend on core facilities in their institutions. If capacities are not sufficient to return output within the time frame of researchers’ planned investigations, deadlines or commitments to collaborators suffer. Technology-related support that can help to augment collaborators’ capabilities in conduct research efficiently and effectively are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Supports for capacity for high volume data storage, processing and transfer.

| Support to augment research capabilities | Category of support |

|---|---|

| Dedicated storage | Technical infrastructure |

| Interoperable storage with other systems (common data model across networked partners) | ” |

| Good choices for data processing capacity and configurations | ” |

| Availability of high capacity data processing and configurations | ” |

| Adequate network protocols with high speed bandwidth | ” |

| Security | Data management |

| Sharable processing workflows/pipelines (QC) | ” |

Primary analysis phase: Workflow, challenges and proposed support Workflow description

During primary analysis the collaborators validate the quality of their respective genomics and transcriptomics datasets. Separately but similarly, they interpret high throughput outcomes; make the data sharable; and ultimately produce validated genotype-phenotype profiles to explore in secondary analysis.

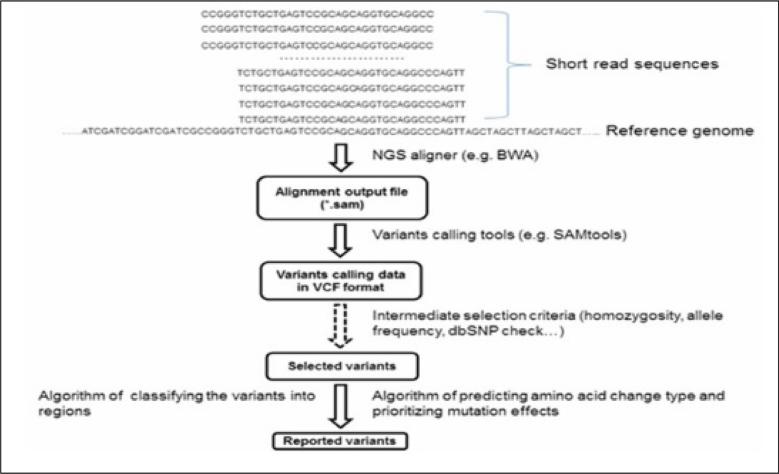

For the genomics data collaborators align sequences to confirm the variants for which the team is looking. The FASTQ reads are aligned using a program (e.g. BWA, http://biobwa.sourceforge.net/); and the aligned reads are stored in one BAM file per person. Researchers use BAM files as input to a variant caller (e.g. GATK, www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). Variant calling is performed in separate chromosome regions, and results are output in a VCF file. Researchers merge VCF files into one main file that contains all variants for all subjects in a cohort. (See Figure 3).

Figure 3. Overview of a variant calling pipeline and file outputs.

Programs for file transformation may be used to convert different formats between tools. (Courtesy of [31])

Collaborating researchers in genomics then perform quality assurance. A biostatistics specialist may work jointly with a bioinformatics expert to apply filters, remove low quality sites, run various quality tests (e.g. allelic balance), and quantify quality scores. At some point after confirming quality collaborators likely convert output to a spreadsheet, which they present to the Principal Investigator of the project to jointly discuss implications of the variants on protein or RNA function. Additional analyses include determining variable sites and the genotype for each individual for each site. Collaborators integrate risk genotypes/haplotypes to expression profiles and patient traits.

During primary analysis of gene expression data collaborators similarly assure quality. For example, they investigate if outliers are tied to microarray output file problems or to batch effects. They seek to identify transcripts for more in-depth study through unbiased and data-driven methods. Using unbiased methods, they run Principal Component Analysis (PCA), examine graphic and tabular output, and define unbiased clusters and subgroupings. They statistically correlate data, and run significant difference analyses (e.g. using such tools as R, ArrayTrack, or MultiExperiment Views (MeV)). Output is often in different formats. For data-driven methods collaborators draw on public sources to annotate and functionally characterize select subgroups of potential interest. They save lists with gene IDs and annotations; combine and re-compile them, as needed; and keep them in forms that can be read into successive programs

Throughout these analyses, as the researchers concentrate respectively on genomics and transcriptomics, the researchers record descriptions (metadata), e.g. of rationales for test choices, parameter settings, assumptions, analysis status of the data, version of tools and data resources, and evaluation criteria. They consult with Principal Investigators and other clinical specialists within and across laboratories at critical points throughout this phase. At some point during this phase, they exchange with each other some ready-to-analyze data to facilitate or enhance the other's analysis. At times, one or the other may ask for raw data. The outcomes of primary analysis are prioritized lists of high interest genetic and gene expression fingerprints associated with patients.

Challenges: Conversion combination, and access of multiple files or datasets

Primary analysis has many objectives – quality control, unbiased analysis, data-driven analysis, derivation of data values or coded variables, offline presentations and discussions, and data exchanges across groups for knowledge building. The number of files, datasets and annotations is often unwieldy. To move analysis and knowledge forward the primary analysts need to tackle the challenge of managing and monitoring data reformatting and file and data merging and conversion. Collaborators who benefit from their data output face the complementary challenge of being able to readily discover and access potentially relevant data/files. Details on both challenges follow.

Managing data and/or file reformatting, merging, and conversion

Frequent format conversions are necessary as researchers turn output from one tool into input for another. To give an idea of the frequency of this challenge, Table 2 encapsulates various tools that could be used in the workflow above and includes secondary analysis, as well. The need for reformatting may occur across many of them.

Table 2.

Tools for managing data/file reformatting, merging, and conversion

| Phase of analysis | Tools |

|---|---|

| Raw data processing | Sanger Illumina |

| Primary analysis-genomics | Sequence alignment tools – BAM output Variant calling - VCF output |

| Primary analysis-transcriptomics | Multiple statistics packages: e.g. R, Bioconductor, ArrrayTrack, MeV Annotation: e.g. Commercial software, DAVID |

| Clinical data | Patient records internally Patient records externally Histopathology outcomes Statistical program – commercial or open source Master file in an updatable form Master file in an archive form for collaborators' uses |

| Secondary analysis – genomics | Integrated file to run sophisticated statistics for logical modeling Input/output for computattional tools for eQTL |

| Secondary analysis – transriptomics | Statistical programs Commercial network programs Cytoscape |

In pipelined flows of analysis conversion may be done automatically. A good deal of analysis in this workflow, however, is not and cannot be pipelined. Computer-savvy bioinformatics researchers may write scripts that will be shared. Table 3 details supports that can mitigate challenges and associated classes of research infrastructure support.

Table 3.

Supports for managing data and/or file reformatting, merging, and conversion

| Support to augment research capabilities | Category of Support |

|---|---|

| Ready availability of shared and/or standard formats | Data management |

| Trustworthy data identifiers | ” |

| Sharable processing workflows | ” |

| Stable, documented application programming interfaces (API) | ” |

| Established and shared methods for combining and sharing data | Openness |

| Easy and timely access to technical expertise for developing/ customizing databases, assuring security, scripting, advanced computing | Service discoverability |

Access/discoverability

Collaborating researchers need mechanisms for efficiently discovering, accessing, and searching available data and files within and across laboratories. Saving files hierarchically on one's desktop or on a low-level share drive does not scale. Maintaining local databases is an improvement but constructing them presents other challenges – namely, finding resources and expertise for their design, development, loading, and testing as well as for the development of intuitive, non-command line user interfaces. For databases, researchers often have to collaborate with IT specialists, either by hiring them to work within the laboratory, by outsourcing, or by gaining services from central IT units.

Beyond accessibly located data collaborating researchers need low cost means for becoming aware of potentially relevant files, outcomes, scripts, pipelines, and algorithms produced in each other's laboratories. They need summary level information with pointers to details. They do not need to be overloaded by routinely receiving actual files, lists of files, or database schema. An awareness of outcome files and methods produced by one collaborating laboratory may trigger researchers in another collaborating laboratory to pursue a line of analysis that they otherwise would not have considered. Overall, many of these discoverability challenges could be met technologically. Data catalogues and indexed assets in searchable collaborative portals could help. So could smart, unobtrusive awareness mechanisms and alerts [15]. These technological approaches, however, are resource-intensive and require computing expertise and IT services. Such costs are rarely built into organization, laboratory or grant budgets as basic collaborative research needs.

Integration: Workflow, challenges and proposed support Workflow description

At some point collaborators across laboratories and institutions benefit by working from a common integrated “master file” or data mart of data generated by the different groups. Collaborators skilled in data integration and statistical analysis likely need to create this master file. To integrate data, these collaborators pull and clean relevant patient data from an institution's electronic record system and merge these records. They also retrieve and merge records from study participants who come from outside institutions. The data integrated into the master file also may include histopathology, genomics and transcriptomics data. Integrating genomics and transcriptomics data often falls to the specific collaborators who respectively analyzed them. They work closely to harmonize their respective files of data, consulting, as needed, with the collaborators who are creating the master file. The genomics and transcriptomics researchers define a structure for mapping the identifiers (IDs) of their data sets to the patient IDs from the clinical data. ID mapping can be time-consuming, with testing and troubleshooting often taking five times longer than writing the mapping script itself. With IDs successfully mapped, select –omics data are merged with clinical and histopathology data into a master file in a statistics package file (e.g SAS). Collaborators in charge of the master file run various statistical analyses on the data in the SAS file. They create an archived version as the master file for global use by collaborators and the renal disease research network.

To let members of a renal disease network community access and query the shared “master data” easily a shared data mart is likely needed. Building and maintaining this platform require collaborations with specialists in Information Technology units and a dedicated administrative “home.” If individual laboratories wish to customize the data mart for their own experiments and projects they may need to have their own computer science capability within the laboratory.

Challenge: Integration of multiple data resources across collaborating groups

Integration is a tedious and labor-intensive process, whether it pertains to pulling, cleaning, and merging patient and ancillary data or to developing and implementing ID mapping schemes. Collaborating researchers need to systematize and share procedures for pulling, cleaning, integrating, and regularly updating clinical data. Harmonizing –omics and patient data and ID mapping require rigorous validation. Moreover, unintentionally this integration may introduce another sort of challenge. Some collaborators may decide to use the master file or data mart for some analyses but rely on their own local database for other analyses. They may prefer their local database because it may be keyed on genomic loci rather than patient ID or because it may have built-in customized queries. This dual use runs the risk of human error. It also may introduce confusion or uncertainty about what information is available and accessible to collaborators, from where, and to whom.

For integration challenges, Table 5 details potentially helpful supports.

Table 5.

Supports for integrating data and datasets

| Support to augment research capabilities | Category of Support |

|---|---|

| Dedicated storage | Technical infrastructure |

| Interoperable databases | ” |

| Trustworthy data identifiers | ” |

| Sharable processing workflows | ” |

| Stable, documented application programming interfaces (API) | ” |

| Established and shared methods for combining/sharing data | Openness |

Secondary analysis phase: Workflow, challenges, and proposed support Workflow description

Researchers now move from descriptive profiling to genotype-phenotype explanations. That is, they seek to uncover possible mechanisms of renal disease by selectively exploring potential biomarkers for cohorts or subgroups and situating them in multiple interactions and functionally relevant contexts. Researchers rely on data from previous phases, and they need to know the processes performed on them and the extent of curation to which the data were subjected. They also may return to earlier files to verify their emerging interpretations and insights.

In the genomics laboratory, collaborators with bioinformatics and biostatistics expertise find and validate significant genotype-phenotype profiles, markers and covariates through such procedures as expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL) analysis and statistically sophisticated logical modeling. They annotate and filter variants. In the gene expression group, collaborators with bioinformatics expertise and deep clinical knowledge seek to uncover and explain a credible and plausible network of interacting genes affecting renal disease – ideally identifying previously unknown relationships. They use numerous exploratory analysis tools to uncover novel and promising gene interactions and pathways. Some tools are commercial (Ingenuity Pathway analysis and Genomatix), and some are open source (Cytoscape, cytoscape.org and The Connectivity Map, broadinstitute.org/cmap). Output from one tool may not be compatible with output from others. This analysis phase involves multidimensional analysis from a number of perspectives. Collaborators, for example, relate genes that are significantly co-regulated to patients with and without a risk allele; they compare unbiased and functional clusters of genes. They analyze transcriptional networks, pathway networks, co-citation networks, and protein-protein interaction networks. By some estimates, 90 per cent of secondary analysis in transcriptomics may be devoted to exploring various types of networks and relating these multiple perspectives for insights. These analyses are exploratory, often ill-structured, and opportunistic. For them, collaborators record metadata and document their analysis workflows/activity trails as best they can. Additionally, as collaborators progressively build knowledge, they may gain insights that lead them to new collaborators. For example, they may start to work with specialists in protein profiling if they find that a previously unknown protein seems to influence genes implicated in the disease.

Challenges: Metadata and unified bioinformatics tools are ill-structured for exploration

Two challenges recur and are particularly vexing in secondary analysis: (a) capturing, saving and sharing metadata; and (b) having unified exploratory tools for cumulatively generating explanations. Details on each follow.

Metadata

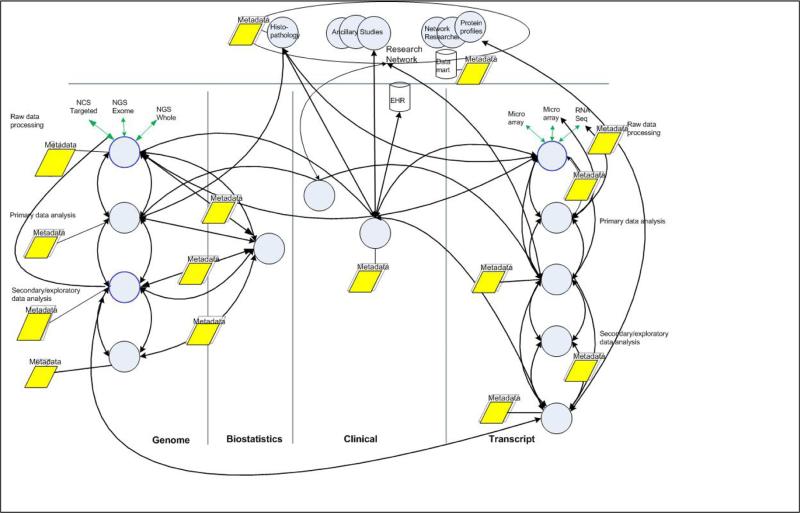

Throughout all phases of the workflow, collaborating researchers need to capture, save, and share readily meaningful metadata. Figure 4 shows at a high level, over a dozen instances of recording metadata occur across phases of analysis for files that researchers expect to share.

Figure 4.

Metadata and files produced in collaborative flows. Captured metadata is colored yellow.

Metadata is particularly vexing for secondary analysis because few bioinformatics tools for this phase have built-in mechanisms for capturing and intelligibly representing the flows of analysis or for tying annotations to series of unfolding analytic objectives and action. Metadata and the contextual content they provide are crucial for transparency, confidence in shared data and methods, facility in search and retrieval, replicability, and the progressive and joint production of credible, plausible knowledge. Relevant metadata content includes information on data provenance, versions, control rights, storage location, codes in the dataset, units of measure, data quality, and meanings of abbreviations [32]. Content may document instruments, algorithms, protocols, and other data science or computational methods. It may explain assumptions and criteria for coding, as well.

Sharing across domains is most productive when content or key terms are standardized for indexing, when definitions are commonly understood, when information is categorized in common, and when it is transformed into usable (machine-readable) form and is extensible [19]. Numerous technologies, software functionalities, mining techniques, IT architectures, and community standards initiatives support constructing such usable metadata for collaborators. But gaps and partial or mismatched functionality exist. For example, common standards and functions for capturing and sharing metadata are more advanced for gene expression than for NGS data or for exploratory and pathway analysis tools. When collaborating laboratories and cross-disciplinary partners do not use community standards or agreed upon taxonomies and terms, metadata often end up in discrete spreadsheets, text files, image files and/or presentation files.

In sum, metadata pose five large challenges for integrative renal disease researchers: (1) knowing prospectively what metadata to capture for collaborators’ needs and purposes; (2) defining jointly with collaborators relevant shared terms, semantic categories, and meanings that are flexible enough for local customizing and having the time to do so; (3) knowing what “technology enablers” for metadata are available institutionally and elsewhere, their comparative strengths and limitations and, most importantly, the combined sets of them that best meet collaborative or research network needs; (4) knowing how to construct workarounds for immediate needs that will adapt to longer range “standard” solutions; and (5) having the capabilities, capacities, and resources to integrate – at contained costs - sets of enablers that can be used and reused.

Addressing these challenges involves perhaps one of the most sweeping range of support needs [4; 9]. As Table 6 shows, supports span numerous categories of research infrastructure requirements and potential improvements.

Table 6.

Supports for metadata challenges across many research infrastructure categories

| Support to augment research capabilities | Category of Support |

|---|---|

| Tool/system with capabilities for data capture and sharing | Technical infrastructure |

| Tools to facilitate/expedite data curation | ” |

| Systems for discovering and accessing metadata | |

| Agreed upon schemes/standards for metadata descriptions | Data management |

| Agreed upon vocabularies, semantics, ontologies | ” |

| Availability of metadata services (e.g. st/repository; standards registry, web-based applications for creating, finding, monitoring reusable metadata, interoperable semantics based on a common data elements and information models) | |

| Stable, documented application programming interfaces (API) | ” |

| Sharable processing workflows | ” |

| Established and shared methods related to metadata | Openness |

| Shared processes for tracking reuse of existing data | ” |

| Interoperable metadata in uses of open source software | ” |

| Stable, documented application programming interfaces (API) | ” |

| Skills in metadata descriptions and identifications | Skill and/or training |

| Easy and timely access to technical expertise | Service/resource discoverability |

Unified tools for exploratory, ill-structured analysis

Tools that collaborators use for secondary analysis have to support a good amount of ill-structured exploratory analysis for drawing and validating explanatory inferences. Moreover, collaborators depend on interacting with multiple tools using various methods in order to examine and test relationships from diverse perspectives for novel insights [25]. For secondary analysis some commercial software enables collaborators to move through libraries of tools/perspectives to visually and statistically explore multi-dimensional and differently scaled relationships without getting overwhelmed. The cost of these applications, however, can be prohibitive for an individual laboratory. For open source bioinformatics tools, the development of useful and usable tools for this cognitively sophisticated level of analysis is only now becoming the next frontier [33]. Additionally, for open source tools little guidance in the bioinformatics literature, at present, directs researchers toward combined sets of tools that together effectively address such questions as “what genes drive differences between patients with different clinical traits, why, and how?” [23].

As challenges, researchers face a need for useful and affordable tools that are well-oriented to actual research questions and knowledge about which tool to use when. They need a relevant set of tools fashioned to a flow of research questions. They also need efficient means for learning to use the tools both individually and as a set; and they need interoperability between the tools themselves and between the tools and publicly available sources and web services. Additionally, researchers have to know what cautions to take when using sets of disparate tools to cumulatively build emerging knowledge. For example, in relating insights from different types of network programs, researchers need to take into account varying levels of curation that may underlie the data displayed by the tools or different built-in algorithms for judging strength of relationships. Similarly, across tools researchers need to know about each tool's reference databases and its methods for deriving concepts or for pre-computing such measures as co-expression or differential expression. Finally, the complexity of explanatory analyses across conceptually similar and disparate tools makes it challenging to capture and annotate workflows efficiently for reuse and sharing across domains, time, and space. Capturing and intelligibly representing activity trails are currently under-developed areas in bioinformatics tools [34]. Table 7 proposes supports for these challenges.

Table 7.

Supports for readily finding and using unified sets of exploratory tools

| Support to augment research capabilities | Category of Support |

|---|---|

| A good choice of complementary analytical tools for formulating hypotheses | Technical infrastructure |

| Services for finding, accessing, and integrating relevant data | ” |

| Knowledge representations and visualizations of relevant data that are sufficient for cumulatively building explanations | ” |

| Tightly coupled statistics, interactive visualizations, and domain knowledge | |

| Stable, documented application programming interfaces (API) | Data management |

| Capture and annotation of activity trails | ” |

| Openness/sharing of workflows/activity trails | Openness |

| Use of open source software | ” |

| Skill in using advanced technologies for exploration/explanation | Skill/ training |

| Discovery of relevant statistical and analytic tools, including interactive visualizations | Service/resource discoverability |

Implications of workflow challenges and associated infrastructural supports

For workflow challenges, the supports that we propose for the research infrastructure have three implications. First, as Tables 1 and 3-7 show, any one area of challenge requires integrated sets of technology-related supports. That is, supports function synergistically for systems level, multi-phase biomedical research. If implemented discretely they may be sub-optimal. Second, researchers often need the same means of support to meet many challenges (e.g. a need for APIs or systems to facilitate data/metadata discovery). Each challenge, however, also has distinct requirements for support. Collaborating researchers need to work with technologists to help them understand the commonalities and distinctions and, thereby, help them plan and ultimately implement research-centric support. Finally, the challenges and support described above reveal that aligning technical, organizational, and researchers’ capabilities is a highly intricate and complex undertaking. Necessary supports span many categories of research infrastructure requirements. Beyond technical infrastructure architectures and processes, these supports involve technical and complementary organizational support for data and information management, openness standards, discoverability of resources and services, and training. Different collaborative projects start with varying levels of research capability and resources, and they may need different types and levels of support. The need to strategically plan necessary support and support improvements cannot be underestimated. Strategic planning needs to include many stakeholders; it needs to provide opportunities for collaborating researchers to give feedback on prototypes and production-ready technologies; and it needs to account for the costs and resources of negotiating and making improvements.

Conclusions

The workflow and challenges described in this essay show that researchers collaborate within groups and across disciplines (e.g. statistics or IT support units). They interact with heterogeneous data and disparate output files, and they request and exchange information and knowledge locally and remotely. Collaborating researchers from specific sub-specialties and at distinct phases of analysis place different emphases on objects of study; but they need to use data and categories in common. Bioinformatics and biostatistics specialists play critical roles. Conversations between researchers and relevant computational and IT experts can help to align technologies to workflow needs and practices [25; 35]. Conversations with health science librarians, biomedical ontologists, and standards committees can do the same for information models [26].

Analysis challenges often outstrip the capacities of any one individual laboratory alone to tackle. Two-way bridges are needed between collaborating researchers and technologists and, by extension, relevant organizational services and the decision makers who set priorities and allocate resources. By and large, these bridges are underdeveloped [11]. This article has looked at one dimension of building bridges – developing an awareness of researchers’ workflows and corresponding challenges. Without stakeholders’ awareness, many wheels will continue to get reinvented; different laboratories will make parallel uses of their own local databases and disparate technologies without a plan in place for harmonizing.

We have proposed combined supports for synergistically addressing workflow challenges. Our continuing research is aimed at further developing our framework of research capabilities categorized by the dimension of the research infrastructure to which various capabilities (and challenges to them) pertain. In this framework, each capability will have a set of specifications (rubrics) describing its possible level of need. Specifications will be based on a scale of increasing collaborative sophistication in the level of activity a capability can enable. The more sophisticated the activity, the greater the capability and its associated support must be. Our vision is for collaborators, technologists, and other (cross-) institutional stakeholders to use this framework to profile collaborating researchers’ current capabilities (activity level) for a given project and to use these profiled requirements to design and develop appropriate technological and organizational supports.

Table 4.

Supports for accessing and discovering relevant data and files

| Support to augment research capabilities | Category of Support |

|---|---|

| Availability of easy to use/populate research network discovery system - with agreed upon access levels | Technical infrastructure |

| Systems for discovering and accessing project-specific resources | ” |

| Dedicated storage | ” |

| Interoperable databases | ” |

| Abilities to find, retrieve and repurpose existing datasets | Skill and/or training |

| Abilities to use and manage data in network discovery systems | ” |

| Established and shared methods for combining and sharing data | Openness |

| Easy and timely access to technical expertise for developing/customizing discovery systems, alerts, and assuring security | Service discoverability |

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: In part by NIH 1 P30 DK081943-01

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None

Contributor Information

Barbara Mirel, School of Education, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Airong Luo, MSIS Research IT, Medical School, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Marcelline Harris, School of Nursing, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

References

- 1.Börner K, Contractor N, Falk-Krzesinski H, Fiore S, Hall K, Keyton J, Spring B, Stokols D, Trochim W, Uzzi B. A multi-level systems perspective for the science of team science. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2:1–5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee ES, McDonald D, Anderson N, Tarczy-Hornoch P. Incorporating collaboratory concepts into informatics in support of translational interdisciplinary biomedical research. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2009;78:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falk-Krzesinski H, Contractor N, Fiore S, Hall K, Kane C, Keyton J, Klein J, Spring B, Stokols D, Trochim W. Mapping a research agenda for the science of team science. Research Evaluation. 2011 2011 Jun;20(2):145–158. doi: 10.3152/095820211X12941371876580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin G, Leung R, Schuchardt K, Garcio D. New paradigms in problem solving environments for scientific computing.. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces; New York. 2002; ACM; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartlidge A, Rudd C, Smith M, Wigzel, Rance S, Shaw S. Wright, TAn introductory overview of ITIL® 2011. itSMF; Norwich, UK: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pipek V, Wulf V. Infrastructuring: toward an integrated perspective on the design and use of information technology. Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 2009;10 [Google Scholar]

- 7.CMMI Product Team . CMMI® for services, Version 1.3: Improving processes for providing better services. Technical Report CMU/SEI-2010-TR-034. Carnegie Mellon University/Software Engineering Institute; Pittsburgh: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyon L, Ball A, Duke M, Day M. Community capability model framework for data-intensive research. [March 8, 2015];White paper. 2012 at: http://communitymodel.sharepoint.com/Documents/CCMDIRWhitePaper-v1-0.pdf.

- 9.Buckow K, Quade M, Rienhoff O, Nussbeck S. Changing requirements and resulting needs for IT-infrastructure for longitudinal research in the neurosciences. Neuroscience Research. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bozeman B, Boardman C. Research collaboration and team science: a state of the art review and agenda. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crowston K, Qin J. A capability maturity model for scientific data management: Evidence from the literature. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2011;48(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lochmuller H. [March 7, 2014];Infrastructural requirements for rare disease within IRDiRC. 2014 at: http://www.rare-diseases.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/0302_Hanns_LOCHM%C3%9CLLER.pdf.

- 13.Payne P, Embi P, Se C. Translational informatics: enabling high-throughput research paradigms. Physiology Genomics. 2009;39:131–140. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00050.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratt W, Reddy M, McDonald DC, Tarczy-Hornoch P, Gennari J. Incorporating ideas from computer-supported cooperative work. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2004;37:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribes D. Ethnography of scaling: Or, how to fit a national research infrastrcuture in the room. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW'14) ACM; New York: 2014. pp. 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ribes D, Finholt T. The long now of technology infrastructure: Articulating tensions in development. Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 2009;10:375–398. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silsand L, Ellingsen G. Generification by translation: designing generic systems in context of the local. Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 2014:15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ure J, Procter R, Lin Y, Hartswood M, Anderson S, Lloyd S, Wardlaw J, Ho K. The development of data infrastructures for eHealth: a socio-technical perspective. Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 2009:10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vertesi J. Seamful spaces: Heterogeneous infrastructures in interaction. Science, Technology & Human Values. 2014;39:264–284. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogel A, Stipelman B, Hall, Nebeling L, Stokols D, Spruijt-Metz D. Pioneering the transdisciplinary team science approach: lessons learned from National Cancer Institute grantees. Journal of Translational Medicine & Epidemiology. 2014;2:1027–1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson JS, Hofer E, Bos N, Zimmerman A, Olson GM. Cooney D, & Faniel IA. theory of remote scientific collaboration (TORSC). In: Olson G, Zimmerman A, Bos N, editors. Science on the internet. MIT Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirel B, Görg C. Scientists’ sense making when hypothesizing about disease mechanisms from expression data and their needs for visualization support. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirel B, Eichinger F, Keller BJ, Kretzler MA. cognitive task analysis of a visual analytic workflow: Exploring molecular interaction networks in systems biology. Journal of Biomedical Discovery and Collaboration. 2011;6:1–33. doi: 10.5210/disco.v6i0.3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirel B. Supporting cognition in systems biology analysis: findings on users' processes and design implications. Journal of Biomedical Discovery and Collaboration. 2009;4 doi: 10.1186/1747-5333-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirel B. Interaction design for complex problem solving: developing useful and usable software. Elsevier; San Francisco: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris MR, Langford L, Miller H, Hook M, Dykes P, Matneyh S. Harmonizing and extending standards from a domain-specific and bottom-up approach: an example from development through use in clinical applications. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association. 2015 doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocu020. Advanced access, http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org.proxy.lib.umich.edu/content/early/2015/02/09/jamia.ocu020.lon.g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Luo A, Zheng K, Bhavnani S, Warden M. Institutional infrastructure to support translational research.. Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Sixth International Conference on e-Science; Washington, DC. 2010; IEEE Computer Society; [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sampson M, Hodgin J, Kretzler M. Defining nephrotic syndrome from an integrative genomics perspective. Pediatric Nephology. 2015;30:51–63. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2857-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller BJ, Martini S, Sedor JR, Kretzler M. A systems view of genetics in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2012;81:14–21. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barisoni L, Nast V, Jennette C, Hodgin J, Herzanberg A, Lemley K, Conway C, Kopp J, Kretzler M, Lienczewski C, Avila-Casado C, Bagnaasco S, Sethi S, Jomaszewski J, Gasin A, Hewitt S. Digital pathology evaluation in the multicenter Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE). Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2013;8:1449–1459. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08370812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bai Y, Cavalcoli J. SNPAAMapper: An efficient genome-wide SNP variant analysis pip3line for next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformation. 2013;9:870–872. doi: 10.6026/97320630009870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenberg J. Metadata and digital information. In: Bates M, Maack M, Drake M, editors. Encyclopedia of library and information science. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gehlenborg N, O'Donoghue S, Baliga N, Goesmann A, Hibbs M, Kitano H, Kohlbacher O, Neuweger H, Schenider R, Tennbaum D, Gaavie A-C. Bisualization of omics data for systems biology. Nathure Methods Supp. 2010;7:556–568. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen C, Johnson CR, Pascucci V, Silva C. Visualization for data-intensive science. In: Hey T, Tansley S, Tolle K, editors. The fourth paradigm: data-intensive scientific discovery. Microsoft; Redmond, WA: 2009. pp. 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chakraborty S, Sarker S, Sarker S. An exploration into the process of requirements elicitation: a grounded approach. Association of Information Systems. Journal. 2010;11(4):212–249. [Google Scholar]