Summary

In the past decade, population genetics has gained tremendous success in identifying genetic variations that are statistically relevant to renal diseases and kidney function. However it is challenging to interpret the functional relevance of the genetic variations found by population genetics studies. In this review, we discuss studies that integrate multiple levels of data, especially transcriptome profiles and phenotype data to assign functional roles of genetic variations involved in kidney function. Furthermore, we introduce state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms, Bayesian networks, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), which have been successfully applied to integrating genetic, regulatory, and clinical information to predict clinical outcomes. These methods are likely to be successfully deployed in the nephrology field in the near future.

Keywords: Gene regulation, SNP, clinical outcomes, predictions

Integrative Biology Gives Functional Interpretation of SNPs identified from population genetics studies

In the past decade, population genetics has gained tremendous success in identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are correlated to the clinical outcomes of the renal diseases. For example, Kopp et al. demonstrated that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a locus on chromosome 22 is correlated to the susceptibility of African Americans to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) [1, 2]. Later on, it was identified that APOL1 in this region is associated with FSGS in African Americans [3]. Additionally, a significant amount of studies have been published to identify SNPs related to diabetic nephropathy. For example, Pezzolesi and colleagues identified a total of 13 SNPs that are associated with Type 1 diabetes-related diabetic nephropathy with p < 1×10−5 [4]. The strongest associated gene FRMD3 was found to be expressed in human kidney [4].

Although genome-wide association studies have been widely used to understand the genetic basis of complex diseases, the follow-up functional studies of the relevant genes are not standardized. Typically, genome-wide association studies conclude by presenting a list of SNPs and their associated genes, leaving the functional analysis for future work. It has become clear that functional characterization of SNPs is fundamental for interpreting the genetic mechanism of diseases. A particular challenge in this regard is SNPs situated in non-protein coding regions of the genome that may impact regulatory function in a manner that is only evident in a certain functional context. One such context may be a biological signaling cascade or pathway determined by genes whose transcription is synchronized by common regulatory elements within their promoters.

Previous studies have employed elegant methods like luciferase reporter gene assays and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to identify those alleles that alter the promoter activity of cis-genes. Identifying promoter-activity-modifying alleles is usually the first step towards the identification of the underlying mechanisms that can be followed by bioinformatics analyses that allow for the identification of potential transcription factors that may be affected by a particular SNP. Several bioinformatics tools, such as TFBS_SEARCH [5], MATCH [6] (developed by the TRANSFAC team) can be used to scan the promoter region for potential binding sites, and then the SNP location can be correlated to the transcription factor binding sites (TFBS). Super-gel shift assays can then be used to verify these interactions if antibodies specific for that particular transcription factor are available. Additional studies could use immunoprecipitation plus massively parallel DNA sequencing (ChIP-Seq) to test whether these transcription factors are indeed involved in the formation of transcriptional complexes at a certain SNP site.

Complexes of several transcription factors often work in concert, in so-called ‘promoter modules’, linked to regulatory patterns or pathways involved in developmental, physiological and pathophysiological responses. Their binding results in an activation or inhibition of target gene expression. These functions are often executed via differentially regulated gene products. These gene products are regulated at the level of transcription initiation by transcription factors that physically and functionally interact with each other and with regulatory sequences within the DNA.

Defining the consequences of regulatory variants on gene expression in complex diseases is still in its infancy also because individual TFBS are often not sufficient for regulatory functions. Their contributions to transcriptional regulation can only be assessed in the appropriate regulatory context, i.e. the regulatory relationships may change across different tissues and diseases. Bioinformatics tools and techniques involving disease-relevant pathways [7, 8], transcriptional co-variance, protein-protein networks [9–12] and phylogenetic conservation [13] have helped to select genes belonging to a certain functional context. With genetic mapping of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) studies becoming available for complex renal diseases, these eQTLs will be linked directly to the physical location of transcripts differentially expressed in kidney diseases and support promoter modeling approaches as described in the following example.

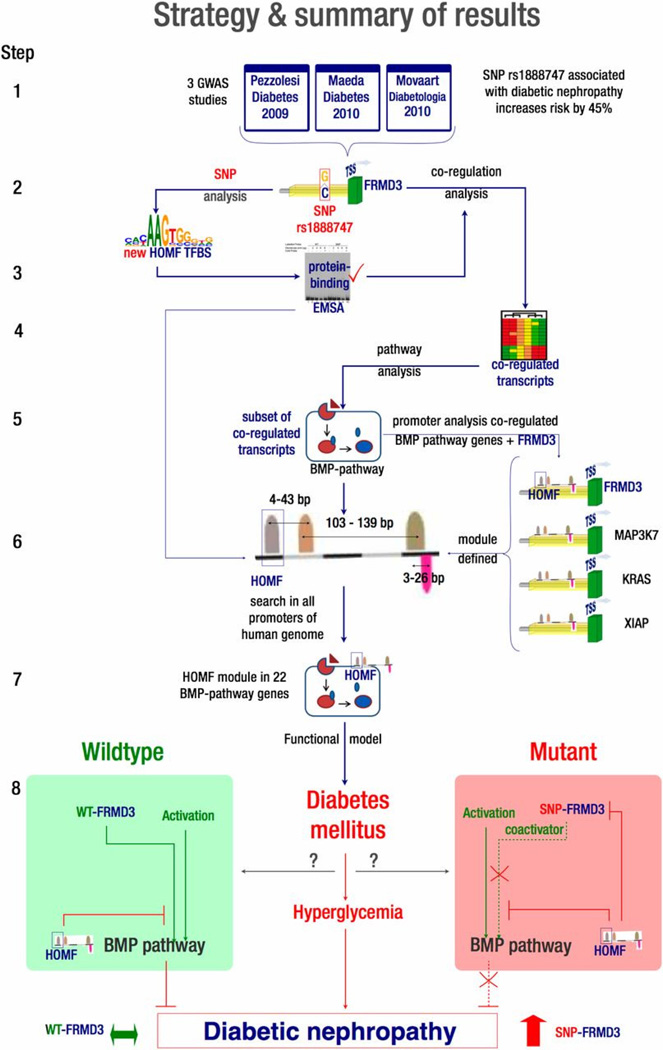

Bioinformatics tools help uncover the functional context of a diabetic nephropathy-associated SNP located in the promoter region of the gene FRMD3

Previous GWAS reported rs1888747 to be significantly associated with diabetic nephropathy [4]. This SNP is located at the non-coding region near FRMD3 and was found to be bound by transcription factors [14]. Using tubulointerstitial gene expression data from kidney biopsies also from patients with diabetic nephropathy, 581 mRNAs that co-express with FRMD3 were identified (Figure 1 for schematic of this study) [14]. These genes are strongly enriched in the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway. In parallel, in silico comparison of sequence variants with and without the risk allele identified a potential homeodomain factor TFBS covering the SNP position. As confirmed by EMSA, this homeodomain factor binding site was absent in the presence of the non-risk allele in the FRMD3 promoter. A set of 4 transcription factors including the homeodomain factor defined by a certain order and distance of each TF – the promoter module, was identified using in silico bioinformatics tools. A genome-wide search then revealed that the promoter framework was enriched among BMP genes as well as the FRMD3 promoter sequence with the risk allele. This led to the hypothesis that the DN risk allele rs1888747 brings FRMD3 under the control of a proposed transcriptional regulatory module and inhibits renal expression of FRMD3. These findings not only detect a transcriptional regulatory pattern affected by the candidate SNP but also connect known DN-associated pathways to the GWAS-derived candidate gene, providing further insight into the pathophysiology of DN that ultimately could lead to individual risk assessments and selection of targeted therapies.

Figure 1. (Courtesy of Diabetes) Strategy to identify the function of the SNP rs 11888747 related to diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes.

The SNP rs11888747 was originally identified through GWAS studies. Co-expression analysis helped to identify the pathways that this SNP might affect. The genes involved in the relevant pathways were then correlated with diabetic nephropathy.

The chronic kidney disease pathway network: crosstalk among multiple molecular mechanisms

Defining the pathophysiology of chronic kidney disease, which affects more than 20 million individuals in the U.S., is critical to identifying predictors of the disease course and potential therapeutic targets. While several mechanisms have been connected with the development of CKD, the CKDGen and CHARGE consortia were able to use GWAS to identify genetic risk factors for renal function decline. Expanding on the concept outlined in the previous paragraph of a single molecular pathway affected by a SNP driving the disease process, the following example provides insight into one possible systems genetics perspective on CKD, where multiple data types are integrated to identify a hierarchy relating candidate genes to co-expressed transcripts as functional relationships. This concept is in line with comprehensive studies in model organisms that show genes and pathways in dense interrelationships, with multiple genes mapping onto multiple pathways that are likely to be contributing or affected in CKD. Genotypic, transcriptomic and clinical data are linked by performing a pathway-crosstalk analysis of the gene sets linked to GFR.

The forty candidate genes identified by the meta-analysis by the CKDGen and CHARGE consortia were located in proximity (+/− 60 kb) of 16 SNPs strongly associated with renal function decline. The majority of these transcripts (29 in total) were found to be expressed above background in renal gene expression profiles of 157 subjects with one of the nine different chronic renal diseases (Focal and Segmental Glomerulosclerosis, Membranous Glomerulonephritis, Minimal-change Disease, Diabetic Nephropathy, Hypertensive Nephropathy, IgA-Nephritis, Lupus Nephritis, Thin-Membrane Disease, or were from histologically unaffected parts of Tumor Nephrectomies).

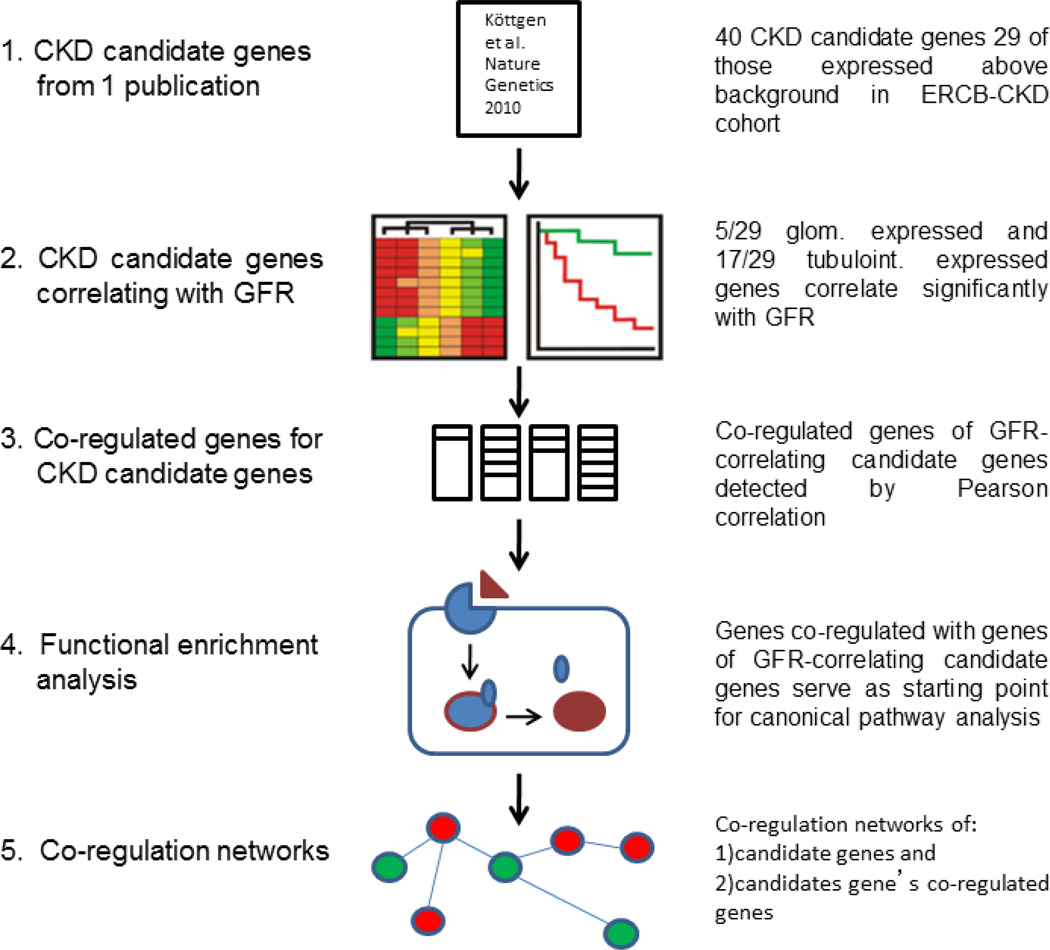

These overlapping genes from the genetic (GWAS) study and the transcriptomic study detected above were further examined for co-expression patterns [15] (Figure 2 for overview of the strategy). Thereby the 18 genes were used as ‘seeds’ to retrieve additional genes correlated with them, resulting in co-expressed gene sets. The biological signaling cascades or pathways enriched among the co-expressed gene sets were identified, and thus linking each gene from population enrichment to gene expression and eGFR correlation and a set of molecular pathways. In total 97 pathways were identified, 56 of them are directly linked to renal function decline, strongly supports that this sequential approach is capable of identifying biologically meaningful candidates. The same analysis was then done on an independent cohort (C-PROBE). 78 of the 97 pathways from the original cohort were re-identified. Finally, for each renal disease included in CKD study, the disease-specific interplay of CKD-related pathways was identified. A disease-disease similarity matrix was established to define the resemblance of the diseases at the molecular level.

Figure 2.

This figure details the strategy that was used to systematically select GFR-associated candidate genes. Those transcripts that share a similar expression pattern as GFR-associated candidate genes were selected. Then, pathway analysis was done on the co-regulated transcripts for biological functionality. Finally, a network of pathways was generated by connecting transcripts co-regulated with CKD-candidate genes.

Integrating large-scale functional genomic data including transcriptomic profiles into context-specific networks

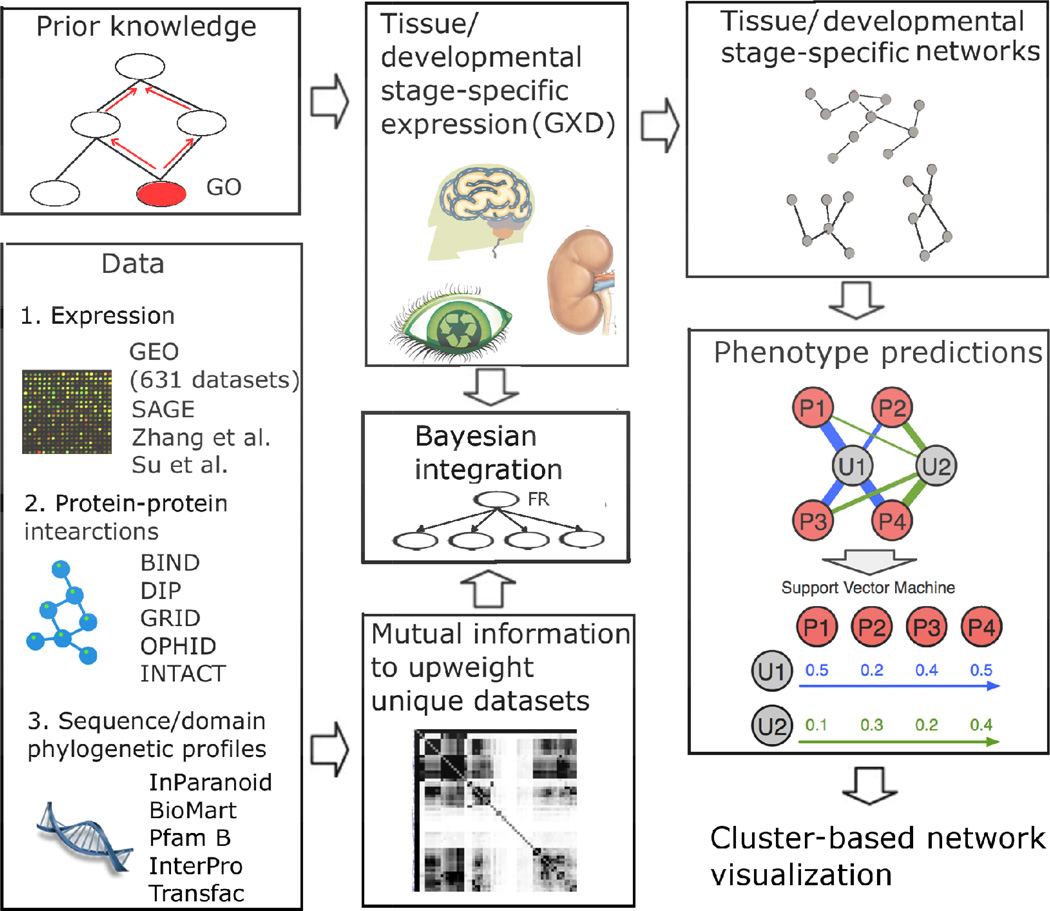

Transcriptomic data are growing exponentially. Diverse methods have been developed to integrate and mine these datasets. Functional relationship network integration is a field utilizing systems biology approaches to integrate the expanding genomic data to understand biology. It offers the potential to complement the reductionist focus of modern molecular biology and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the causal relationships leading to normal and abnormal phenotypes. These networks summarize the probability of co-functionality between any two genes in the genome, and thus offer a key path to systematically understand the biological processes in an organism. Functional networks can be generated through Bayesian classifiers [9–13, 16] or machine learning approaches [17]. Despite the differences in the exact methods used to infer probability, the methods used to generate functional relationship networks can be summarized into three steps (Figure 3). First, a ‘Gold Standard’ set is defined, which consists of protein pairs that are known to work in the same biological process or pathway. The ‘Gold Standard’ set is often defined through co-annotation to a specific Gene Ontology term [18], KEGG [7], NCI pathways [19] and/or BioCyc pathways [8]. These are standard databases that record annotations of gene functions. Annotations in Gene Ontology are typically arranged in a hierarchy, where very broad terms include many genes, and specific terms include fewer genes. Thus, to define co-functionality, often a cutoff in specificity of the GO terms is applied. Secondly, diverse genomic datasets are collected from public databases, including many expression datasets (typically hundreds), physical interactions, genetic interactions, phylogenetic profiles, phenotypes, and domain/sequence similarity. Because of the availability of RNA-seq data (in addition to microarray data), which is capable of profiling the expression at the alternatively splieced isoform level, similarly, such networks can be generated at the alternatively spliced isoform level [20], and thus functions inferred for isoforms [21–23]. The reliability of each dataset is quantified against the gold standard co-functional gene pairs through certain statistical measurement, such as Bayesian statistics. At this step, mutual information may be used to evaluate the overlap between datasets. Finally, probabilistic models are constructed to integrate diverse datasets based on how accurate they are in recovering the ‘gold standard’ set. Such networks can be used for prioritize disease-associated genes. Based on this global network, machine learning tools can be developed to mine this functional network to prioritize disease-related genes as a complementary approach to quantitative genetics. A widely used tool, Support Vector Machines, has been used to explore the network structure and predict the functions and disease associations of genes [9, 24]. In previous benchmark studies, SVM has been shown to be the top performing method in this field [25].

Figure 3. Overview of the strategies to model functional relationship networks and to use these networks to predict phenotypes and functions of genes.

A Bayesian framework can be used to integrate prior knowledge, a large number of genomic datasets, tissue and stage-specific expression data. Prior knowledge, i.e.gold standard pairs of functionally related pairs, can be gathered from Gene Ontology, KEGG and BioCyc pathways. For each tissue, the global gold standard pairs are restricted to pairs that both members are expressed in that tissue. Genome-scale data, including physical interactions [30–35], expression (GEO and SRA), sequence and domain information are collected and transformed into pairwise gene-gene scores. The overlap between different data sources can be quantified through mutual information calculation. A mutual information-regulated Bayesian network can thus be constructed to weigh and integrate all genome-scale datasets together to infer the final tissue and stage-specific networks. Support vector machine (SVM)-based algorithm can be used to mine the tissue specific networks to predict genes related to phenotypes. These networks can also be visualized through publicly available software so that biologists can explore these networks through interactive webpages.

Most interestingly, in human and mouse, it has been shown that tissue-specific expression data could be built into this Bayesian framework to generate tissue-specific networks that are more accurate in capturing space-specific events (Figure 3). The basic intuition is that for a specific tissue, proteins are co-present to function in the same biological process. Therefore, a gold standard pair for a specific tissue must satisfy two criteria: 1. the members of the pair are functionally related; 2. Both members must be expressed in this tissue under investigation. It has been shown that tissue-specific networks out-performed global network in predicting phenotype and functions of genes [9].

Such functional relationship networks have also been applied to longitudinal expression data to generate dynamic networks that capture the changes of the interactions between genes across a time-course. For example, an algorithm was recently developed to leverage both differentiation stage-specific expression data and large-scale heterogeneous functional genomic data to model dynamic changes of biological networks. This algorithm was applied to time-course RNA-Seq data for ex vivo human erythroid cell differentiation [12]. The networks correctly predict the (de)-activated functional connections between genes during erythropoiesis. Critical genes driving erythropoiesis and functional connections during erythropoiesis can be revealed using these dynamic networks. This interesting method of modeling dynamic networks is applicable to data collected at several stages of renal diseases such as diabetes, and should assist in generating greater understanding of the functional dynamics at play across the genome during disease progression.

Emerging techniques to integrate SNPs, transcriptome and clinical profiles to predict clinical outcomes

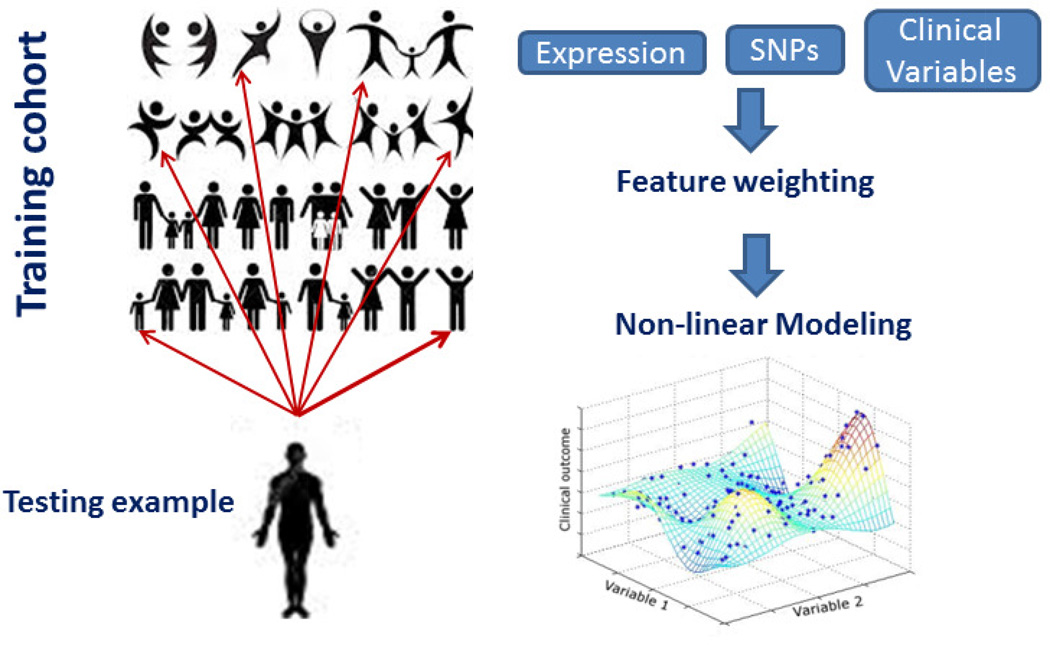

In the past decades, predicting the drug responses and prognosis based on multiple-levels of data integration has been a major focus of systems biology at large. These studies can help to define the disease uniquely for each patient and thus offer the possibility of precision medicine. For consecutive years, the Dialogue for Reverse Engineering Assessments and Methods (DREAM) challenges have devoted at least one challenge to predicting the clinical outcomes for complex diseases. DREAM is the largest, community-based, blind assessment for catalyzing the interaction between experiment and theory in the area of cellular network inference and quantitative model building in systems biology [26]. The sole evaluation criterion of DREAM is the accuracy of the algorithms submitted by different teams, evaluated on blind, previously unseen experimental test data. In the past years, a novel method, customized Gaussian Process Regression (cGPR) (Figure 4), has arisen as the best-performing method in multiple benchmark studies. In the 2014 DREAM Rheumatoid Arthritis drug responder challenge, this method achieved the top accuracy in both the genetics-only model and clinical and genetics information combined model, for all sub-challenges measuring different clinical prognoses in response to different drugs, and for all test sets [27]. In the 2014 DREAM Alzheimer’s Diseases Big Data challenge, cGPR was the best-performing method for identifying AD patients based on brain image data [28]. In all cases, multiple sources of data, including SNPs, transcriptomic data, clinical information and/or images were used in establish these models. cGPR can often quickly out-perform the state-of-the-art models in various field, making it a transformative technology in the clinical outcome prediction field. Below, we will describe the rationale, basic algorithms and unique properties of cGPR, which allows it to become a superior method compared to classical methods used in the clinical outcome prediction field.

Figure 4. Illustration of customized Gaussian Process Regression for clinical outcome prediction.

First, individual features, which can be individual gene expression patterns, clinical features, SNPs, are assigned a weight according to their correlation to the clinical outcome to be predicted (the ‘customized’ step). To predict the clinical outcome of a patient, his/her similarity to other patients in this weighted feature space will be measured through co-variance functions and the most similar patients in the training cohort will contribute more to the predicted score of this patient in the test cohort.

The fundamental property of cGPR is that unlike other mainstream regression methods that take all training examples into consideration simultaneously, GPR predicts the treatment response for an individual patient by computing a weighted average of one to several most similar examples in the training set. Thus the weighting of different training examples is 'personalized' to each test example. Compared to other regression/classification methods, GPR is capable of satisfying three key factors we often encounter in integrating multiple sources of data. First, the relationship between the clinical outcomes and the features, such as gene expression, SNPs, and other clinical parameters, cannot be modeled through a simple linear, logarithmic, power or polynomial function. Most of the current regression methods rely on a modeling function to fit the relationship between different clinical features and the outcome (e.g., linear regression, logistic regression). This assumption may often be incorrect, because real-world patient data may not have a simplified relationship.

Second, the relative importance of different SNPs and baseline clinical information in determining the outcome may vary between individuals. cGPR allows customized adjusting of individual factors by its importance in predicting clinical outcomes. This is a useful feature, since in many cases, a single biomarker may be extremely predictive for an outcome and thus its weight has to be adjusted higher than others. This feature can either be determined by data-driven approaches, such mutual information and correlation, or by biological expertise. For example, in the 2014 DREAM Alzheimer’s Disease Big Data Challenge, the winning team gave the most predictive feature, the volume of hippocampus half of the entire weight in the prediction model. Such customized weight is not achievable in other prevailing models.

Third, cGPR is robust to a heterogeneous population and to the disparity between different cohorts. When pooling data from several cohorts together, often the most significant SNPs identified using traditional methods reflect the disparity between cohorts rather than being predictive of the drug response. This is indeed observed in many models, in which densely sampled populations contribute more than the models that are less sampled. In cGPR, only the examples that manifest similar genetic and clinical characteristics should be considered for a specific patient to be predicted. The rest of the examples should be given much less weight due to intrinsic heterogeneity between individuals. Intrinsically, cGPR is an interpolation method, with only similar examples used. Another unique feature of cGPR is that it is capable of dealing with missing features, which is commonly seen in real-world clinical data. For patients with missing parameters, their predictions are generated with the other parameters re-weighted.

This cGPR approach has been shown tremendous success in numerous benchmark studies in other field. The above feature will likely become extremely important in predicting the clinical outcomes for kidney diseases. For example, we are actively deploying this technique to the data collected from the NEPTUNE cohort. The NEPTUNE cohort collects rich resources of molecular profiles, gene expression data, phenotypic and genetic data for nephrotic syndromes [29]. In nephrotic syndromes, often the most significant predictor of GFR slope is the baseline GFR, for which cGPR could give much more weight than other parameters. Additionally, the non-linear relationship between baseline and outcome can be easily modeled with cGPR.

Conclusions

The era of microarray and RNA-seq has allowed profiling of genome-wide expression patterns efficiently. This article reviews recent advances in integrating transcriptomic data as well as clinical data to identify relevant renal disease genes and predict clinical outcomes. We introduced several state-of-the-art integrative approaches that assign functional roles to SNPs identified through population genetics studies. We also introduced new development in algorithms of clinical outcome prediction in the bioinformatics field.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kopp JB, et al. MYH9 is a major-effect risk gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1175–1184. doi: 10.1038/ng.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kao WH, et al. MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1185–1192. doi: 10.1038/ng.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genovese G, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329(5993):841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pezzolesi MG, et al. Genome-wide association scan for diabetic nephropathy susceptibility genes in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58(6):1403–1410. doi: 10.2337/db08-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee C, Huang CH. Searching for transcription factor binding sites in vector spaces. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:215. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kel AE, et al. MATCH: A tool for searching transcription factor binding sites in DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3576–3579. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogata H, et al. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27( 1):29–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caspi R, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of Pathway/Genome Databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D459–D471. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan Y, et al. Tissue-specific functional networks for prioritizing phenotype and disease genes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(9):e1002694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong AK, et al. IMP: a multi-species functional genomics portal for integration, visualization and prediction of protein functions and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W484–W490. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guan Y, et al. A genomewide functional network for the laboratory mouse. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4(9):e1000165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu F, et al. Modeling dynamic functional relationship networks and application to ex vivo human erythroid differentiation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(23):3325–3333. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park CY, et al. Functional knowledge transfer for high-accuracy prediction of under-studied biological processes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(3):e1002957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martini S, et al. From single nucleotide polymorphism to transcriptional mechanism: a model for FRMD3 in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2013;62(7):2605–2612. doi: 10.2337/db12-1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martini S, et al. Integrative biology identifies shared transcriptional networks in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(11):2559–2572. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan Y, et al. Functional genomics complements quantitative genetics in identifying disease-gene associations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6(11):e1000991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chikina MD, et al. Global prediction of tissue-specific gene expression and context-dependent gene networks in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(6):e1000417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaefer CF, et al. PID: the Pathway Interaction Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D674–D679. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li HD, et al. Revisiting the identification of canonical splice isoforms through integration of functional genomics and proteomics evidence. Proteomics. 2014;14(23–24):2709–2718. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li HD, et al. The emerging era of genomic data integration for analyzing splice isoform function. Trends Genet. 2014;30(8):340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Omenn GS, Guan Y, Menon R. A new class of protein cancer biomarker candidates: differentially expressed splice variants of ERBB2 (HER2/neu) and ERBB1 (EGFR) in breast cancer cell lines. J Proteomics. 2014;107:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eksi R, et al. Systematically differentiating functions for alternatively spliced isoforms through integrating RNA-seq data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(11):e1003314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan Y, et al. Predicting gene function in a hierarchical context with an ensemble of classifiers. Genome Biol. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-s1-s3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pena-Castillo L, et al. A critical assessment of Mus musculus gene function prediction using integrated genomic evidence. Genome Biol. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-s1-s2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. http://dreamchallenges.org/.

- 27. https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn1734172/wiki/65264.

- 28. https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn2290704/wiki/70719.

- 29.Gadegbeku CA, et al. Design of the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE) to evaluate primary glomerular nephropathy by a multidisciplinary approach. Kidney Int. 2013;83(4):749–756. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alfarano C, et al. The Biomolecular Interaction Network Database and related tools 2005 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database issue):D418–D424. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aranda B, et al. The IntAct molecular interaction database in 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D525–D531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ceol A, et al. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D532–D539. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jayapandian M, et al. Michigan Molecular Interactions (MiMI): putting the jigsaw puzzle together. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D566–D571. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stark C, et al. The BioGRID Interaction Database: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D698–D704. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mewes HW, et al. MIPS: a database for genomes and protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):31–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]