Abstract

While microRNAs have emerged as an important component of gene regulatory networks, it remains unclear how microRNAs collaborate with transcription factors in the gene networks that determines neuronal cell fate. Here, we show that in the developing spinal cord, the expression of miR-218 is directly upregulated by the Isl1-Lhx3 complex, which drives motor neuron fate. Inhibition of miR-218 suppresses the generation of motor neurons in both chick neural tube and mouse embryonic stem cells, suggesting that miR-218 plays a crucial role in motor neuron differentiation. Results from unbiased RISC-trap screens, in vivo reporter assays, and overexpression studies indicated that miR-218 directly represses transcripts that promote developmental programs for interneurons. Additionally, we found that miR-218 activity is required for Isl1-Lhx3 to effectively induce motor neurons and suppress interneuron fates. Together, our results reveal an essential role of miR-218 as a downstream effector of the Isl1-Lhx3 complex in establishing motor neuron identity.

Keywords: microRNA, miR-218, Isl1, Lhx3, NLI, LDB, motor neurons, hexamer, complex, spinal cord, development

INTRODUCTION

Throughout development of the central nervous system (CNS), a vast number of neuronal types are produced with striking precision. Understanding the intricate gene regulatory networks, which establish the unique identity of each neuronal cell type and eventually lead to the great cellular complexity in the CNS, is an important topic in neurobiology.

In the developing spinal cord, neuronal cell fate specification is initiated by the integration of morphogen gradients that direct the patterning of progenitor domains, each of which gives rise to a specific neuronal type1–3. The boundaries of the progenitor domains are sharpened by cross-repressive interactions between transcription factors that are expressed in neighboring progenitor domains2,4–6. As progenitor cells exit the cell cycle, transcription factors that promote the differentiation of distinct interneuron types and motor neurons are upregulated3,7. Two LIM-homeodomain factors, LIM homeobox 3 (Lhx3) and Islet-1 (Isl1) are co-expressed in differentiating motor neurons, while Lhx3, but not Isl1, is expressed in newly born V2 interneurons8–11. Isl1 and Lhx3 form a hexameric Isl1-Lhx3 transcription complex with nuclear LIM interactor (NLI) (Fig. 1a)12. The co-expression of Isl1 and Lhx3, along with neurogenic factors, triggers the generation of motor neurons in various cellular contexts, such as the dorsal spinal cord, embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells7,12–18. This potent activity of Isl1-Lhx3 that drives motor neuron fate specification is partly attributed to the fact that Isl1-Lhx3 directly binds and robustly upregulates a wide range of terminal differentiation genes, including a battery of cholinergic pathway genes that enable cholinergic neurotransmission13,17–19. Another critical factor is that the Isl1-Lhx3 complex inhibits the acquisition of non-motor neuron fates, as evident from the observation that Isl1-Lhx3 suppresses the interneuron programs in ESCs that are directed to differentiate into neurons13. However, the mechanisms by which Isl1-Lhx3 represses interneuron differentiation or progenitor fate remain unknown.

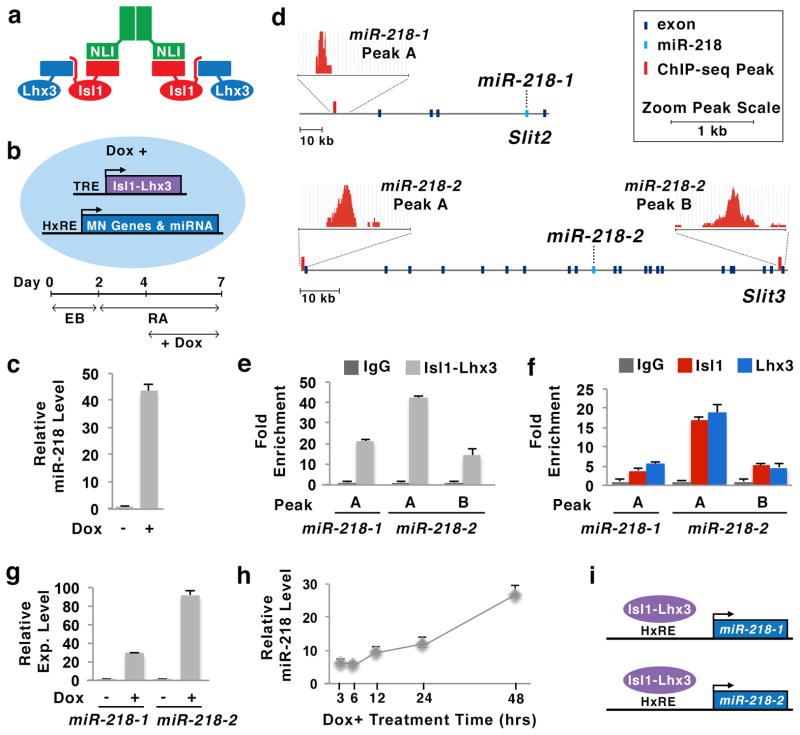

Figure 1. Identification of miR-218 as a direct target miRNA of Isl1-Lhx3 in motor neurons.

(a) Illustration of the Isl1-Lhx3 hexamer complex, consisting of two NLI, two Isl1 and two Lhx3 proteins.

(b) Schematic model of Isl1-Lhx3 embryonic stem cell (Isl1-Lhx3-ESC) line and the experimental design to differentiate Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs to neurons. Treatment with doxycycline (Dox) induces the expression of Isl1-Lhx3, which is controlled by tetracycline response element (TRE), in Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs. Then, Isl1-Lhx3 upregulates its direct target genes that have hexamer response element (HxRE), such as motor neuron (MN) genes and miRNAs. EB, embryoid bodies; RA, retinoic acid.

(c) Isl1-Lhx3 triggered the expression of mature miR-218 in Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs, as determined by qPCR using TaqMan probes. Error bars represent the standard deviation. n = 2, biological duplicates.

(d) Isl1-Lhx3-bound ChIP-seq peaks were identified near miR-218-1 and miR-218-2 genes, within the introns of Slit2 and Slit3, respectively.

(e) Isl1-Lhx3 bound to three Isl1-Lhx3-bound ChIP-seq peak regions near miR-218-1 and miR-218-2 genes in Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs. Error bars represent the standard deviation. n = 3.

(f) Both Isl1 and Lhx3 were recruited to three Isl1-Lhx3-bound ChIP-seq peaks near miR-218-1 and miR-218-2 genes in E12.5 mouse spinal cord. Error bars represent the standard deviation. n = 3.

(g) Isl1-Lhx3 induced the expression of pri-miR-218-1 and pri-miR-218-2 in Isl1-Lhx3-ESC-derived motor neurons, as determined by qPCR using TaqMan probes. Error bars represent the standard deviation. n = 2.

(h) Isl1-Lhx3 strongly upregulated miR-218 expression within 48 hours in Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs cultured in monolayer without retinoic acid, as determined by qPCR using TaqMan probes. Error bars represent the standard deviation. n = 3.

(i) Isl1-Lhx3 complex binds to hexamer response element (HxRE) near miR-218-1 and miR-218-2 genes and triggers the expression of miR-218 genes in differentiating MNs.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small RNA molecules that bind to target mRNAs and prevent translation or trigger degradation of their target transcripts20. A growing body of research has established that miRNAs serve as a crucial constituent of gene regulatory networks. Recent studies of miRNAs in the developing spinal cord have revealed that miR-124 and miR-17-3p play a role in neuronal differentiation and progenitor domain patterning, respectively21–23, and that miR-9 is involved in fine-tuning the differentiation of motor neuron subtypes24–26. However, it remains unclear how miRNAs are interconnected with cell fate-specifying transcription factors in the regulatory networks that determine neuronal cell fates in CNS development.

In this study, we investigated the role of miRNAs in the gene networks that specify motor neuron fate. We found that a single miRNA, miR-218, is highly and directly upregulated by Isl1-Lhx3 at the onset of motor neuron differentiation and that miR-218 is specifically expressed in motor neurons throughout spinal cord development. We also found that miR-218 is essential for the generation of motor neurons both in vitro and in vivo. Our RISC-trap screen revealed many miR-218 target transcripts whose primary function is to promote interneuron or neural progenitor characteristics in the spinal cord. Consistently, miR-218 was needed for Isl1-Lhx3 to efficiently suppress interneuron programs and promote motor neuron fate in neural progenitors. Together, our results suggest that miR-218 functions as a crucial downstream effector of the Isl1-Lhx3 complex in establishing motor neuron identity by downregulating genes that promote non-motor neuron fates. Our study highlights an intricate gene regulatory network in which cell fate-specifying transcription factors cooperate with downstream miRNAs to define the gene expression profile for an appropriate cell fate.

RESULTS

miR-218 is upregulated during motor neuron differentiation

To identify miRNAs that play a role in promoting motor neuron cell fate, we took advantage of Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs, which serve as a robust model of motor neuron differentiation13,19. Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs express an Isl1-Lhx3 fusion protein upon doxycycline (Dox) treatment, which forms the Isl1-Lhx3 hexamer complex with endogenous NLI (Fig. 1a, b). Upon treatment with Dox and retinoic acid (RA) following the formation of embryoid bodies (EBs), Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs differentiate into motor neurons, which express numerous motor neuron markers and form neuromuscular junctions with myotubes13. To systemically monitor the expression pattern of miRNAs during motor neuron differentiation in Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs in an unbiased manner, we determined the expression profiles of miRNAs in RA-treated Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs, incubated either with or without Dox (i.e. expression of Isl1-Lhx3), using a TaqMan miRNA array. Pairwise comparison of miRNA arrays revealed that 18 miRNAs are induced more than 3 fold (Table 1, Supplementary Data 1). Interestingly, a single miRNA, miR-218, showed a remarkable ~ 71 fold induction, while the next highest induced miRNA, miR-382, was upregulated by ~ 9 fold. Additionally, miR-218 was the fifth highest expressed miRNA in Dox-treated conditions, indicating that miR-218 is abundantly present in embryonic motor neurons. The expression levels of other miRNAs that are implicated in the development of motor neurons, such as miR-924–26, miR-12421,22, and the miR-17-92 cluster23, were unaltered between Dox-treated versus Dox-untreated conditions. Our independent TaqMan quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses confirmed the robust upregulation of miR-218 in Dox-treated conditions (Fig. 1c). These results suggest that miR-218 may play a role in motor neuron cell fate specification downstream of the Isl1-Lhx3 complex.

Table 1. Selected miR-218 RISC-trap target mRNAs.

A list of miRNAs that exhibit a significant induction by Dox treatment (> 3-fold, p < 0.05), as determined by TaqMan miRNA arrays. Expression rank (Exp. Rank) describes the rank of relative expression levels of each miRNA in Dox-treated conditions.

| microRNA | Fold Change | P-Value | Dox+ Exp. Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-218 | 70.76 | 0.006 | 5 |

| miR-382 | 8.89 | 0.034 | 87 |

| miR-203 | 6.57 | 0.045 | 142 |

| miR-200a | 4.30 | 0.043 | 114 |

| miR-376c | 4.15 | 0.047 | 62 |

| miR-411 | 3.28 | 0.048 | 34 |

| miR-26b | 3.27 | 0.044 | 54 |

| miR-28 | 3.27 | 0.049 | 110 |

| miR-495 | 3.24 | 0.046 | 82 |

| miR-106b | 3.23 | 0.047 | 32 |

| miR-224 | 3.23 | 0.049 | 166 |

| miR-34b-3p | 3.22 | 0.049 | 120 |

| miR-539 | 3.20 | 0.050 | 56 |

| miR-29a | 3.20 | 0.049 | 111 |

| miR-362-3p | 3.18 | 0.046 | 222 |

| miR-379 | 3.06 | 0.021 | 72 |

| miR-145 | 3.05 | 0.022 | 132 |

| miR-350 | 3.03 | 0.025 | 210 |

Isl1-Lhx3 directly upregulates miR-218-1 and miR-218-2 genes

miR-218 is an evolutionarily conserved miRNA that is encoded in introns of Slit2 and Slit3 genes, which produce miRNA precursor hairpins pri-miR-218-1 and pri-miR-218-2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). To test whether the Isl1-Lhx3 complex directly regulates the expression of miR-218 genes, we analyzed the genome-wide binding pattern of Isl1-Lhx3 using two independent ChIP-seq datasets13,17. Interestingly, Isl1-Lhx3-bound ChIP-seq peaks were found in the introns of both Slit2 and Slit3 genes (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 2,3). Our ChIP analyses in Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs further confirmed that Isl1-Lhx3 binds to the ChIP-seq peaks in Slit2 and Slit3 genes (Fig. 1e). Next, the ChIP assays in E12.5 mouse spinal cord using anti-Isl1 and anti-Lhx3 antibodies revealed that both Isl1 and Lhx3 are recruited to the ChIP-seq peaks in Slit2 and Slit3 genes in vivo (Fig. 1f).

The binding of Isl1-Lhx3 to miR-218-1 and miR-218-2 loci suggests that the upregulation of mature miR-218 by Isl1-Lhx3 is attributed to the direct induction of both miR-218 genes. Indeed, miR-218-1 and miR-218-2 pri-miRNAs were markedly upregulated during Isl1-Lhx3-directed motor neuron differentiation in ESCs (Fig. 1g). To further determine whether the upregulation of miR-218 genes is a direct outcome of transcriptional activation of the genes by Isl1-Lhx3 or an indirect outcome of motor neuron differentiation, we expressed Isl1-Lhx3 in ESCs without triggering motor neuron differentiation. When Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs are cultured in a monolayer without RA, the ESCs do not differentiate into neurons. In this condition, we treated Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs with Dox (i.e. expression of Isl1-Lhx3), collected cells at multiple time points and monitored the miR-218 levels. Interestingly, Isl1-Lhx3 expression still led to a drastic upregulation of miR-218 (Fig. 1h). These results suggest that Isl1-Lhx3 directly induces the expression of miR-218 independently of motor neuron differentiation.

Together, our data demonstrate that the Isl1-Lhx3 complex upregulates both miR-218-1 and miR-218-2 genes by directly binding to both genes during motor neuron differentiation (Fig. 1i).

miR-218 is specifically active in developing motor neurons

The robust upregulation of miR-218 in ESC-derived motor neurons prompted us to investigate the in vivo expression pattern of miR-218 in developing embryos. In situ hybridization analyses revealed that miR-218 is specifically upregulated in motor neurons during cell fate specification (Fig. 2a–c, Supplementary Fig. 4a). miR-218 maintains its motor neuron-specific expression pattern in the spinal cord throughout embryonic development (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 4a).

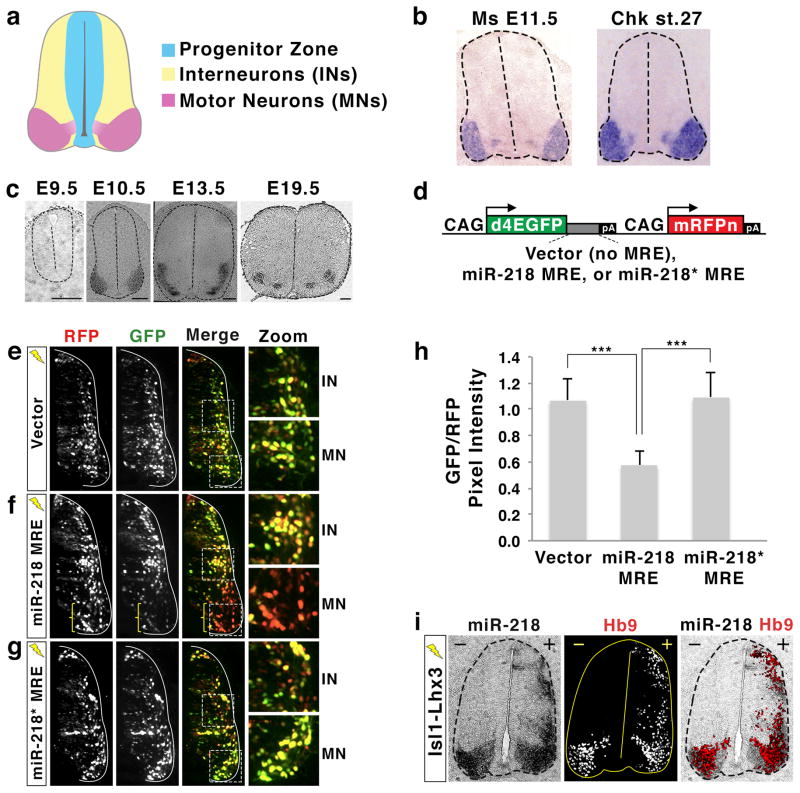

Figure 2. miR-218 is expressed and functional in embryonic motor neurons.

(a) Illustration of the developing spinal cord. Stereotypical locations of progenitor cells, interneurons (INs), and motor neurons (MNs) in mouse E11.5 and chicken HH St.27 embryos are shown.

(b) miR-218 is specifically expressed in motor neurons of mouse and chick embryos, as shown by in situ hybridization with a probe detecting mature miR-218.

(c) miR-218 is induced at the onset of motor neuron differentiation and continues to be expressed in motor neurons throughout mouse embryonic development, as shown by in situ hybridization with a probe detecting mature miR-218. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(d) Illustrations of miRNA sensor plasmids. The multimerized microRNA response element (MRE) for miR-218 or miR-218* was inserted between the destabilized EGFP (d4EGFP) gene and polyA (pA) sequences. The expression of both d4EGFP and mononuclear RFP (mRFPn) is driven by two separate, ubiquitously active CAG promoters.

(e–g) The expression pattern of GFP and RFP in the chick spinal cord electroporated with miRNA sensor vector (e), miR-218 MRE sensor (f) or miR-218* MRE sensor (g). Only electroporated side of the spinal cord is shown. GFP expression is regulated by endogenous miRNA that binds to the MREs present in 3′UTR of the GFP gene, while RFP expression depicts the electroporated cells. The areas of interneuron (IN) and motor neuron (MN) are magnified. The miR-218 MRE sensor shows drastically down-regulated GFP expression in motor neuron area (bracket in f), indicating that endogenous miR-218 in motor neurons suppresses the expression of GFP.

(h) Quantification of relative pixel intensity of GFP/RFP in motor neurons, as quantified using ImageJ program. Error bars represent the standard deviation. ***p < 0.0001 in two-tailed Student’s t-test. n = 5 embryos.

(i) Analyses using serial sections from the same chicken embryo electroporated with Isl1-Lhx3. In situ hybridization for miR-218 and immunohistochemical analyses with Hb9 antibody reveals that the expression of miR-218 was highly induced by Isl1-Lhx3 in the dorsal spinal cord, where Hb9+ ectopic motor neurons are formed. +, electroporated side; −, unelectroporated control side.

To determine where endogenous miR-218 actively suppresses target gene expression in vivo, we used miRNA sensor plasmids, in which a cytomegalovirus/chicken β actin (CAG) promoter drives the expression of a destabilized nuclear GFP with a half-life of 4 hours (d4EGFP) that is linked with complete complementary miRNA response elements (MREs) (Fig. 2d)21. The miRNA sensor plasmids also have another CAG promoter directing the expression of monomeric nuclear RFP (mRFPn). To assess the endogenous activity of miR-218 in embryonic spinal cord, we electroporated chick neural tubes with either miRNA sensor vector or miR-218 sensor, in which miR-218 MREs are inserted into the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the d4EGFP. We then monitored the expression levels of GFP compared to RFP, which labels all transfected cells, three days after electroporation. In ovo electroporation of miRNA sensor vector resulted in the expression of GFP and RFP in similar ratios throughout the spinal cord (Fig. 2e, h). In contrast, the miR-218 sensor showed a drastic downregulation of GFP specifically in motor neurons, compared to interneurons (Fig. 2f, h), indicating that endogenous miR-218 actively represses target genes with miR-218 MREs in developing motor neurons.

It is possible that both strands of an miRNA precursor hairpin are expressed and actively repress mRNA targets27. To test whether the complementary miR-218-3p “star” strand is also active in motor neurons, we generated a miR-218-star sensor. We did not observe any regional differences between motor neurons and interneurons in GFP/RFP pixel intensity in chick spinal cord electroporated with the miR-218-star sensor (Fig. 2g, h), suggesting that the miR-218-star strand is not functional in the developing spinal cord.

Together, our results demonstrate that miR-218, but not miR-218-star, is selectively expressed and actively represses its target genes with miR-218 MRE in motor neurons.

miR-218 is induced by Is1-Lhx3 in the embryonic spinal cord

The specific and robust upregulation of miR-218 in newly born motor neurons during spinal cord development, along with a marked and direct induction of miR-218 by Isl1-Lhx3 during motor neurogenesis of ESCs, point to the possibility that miR-218 functions downstream of the Isl1-Lhx3 complex in developing motor neurons. To test this possibility in vivo, we misexpressed Isl1-Lhx3 in the chick neural tube and monitored the expression patterns of miR-218 using in situ hybridization analyses. Isl1-Lhx3 ectopically induced the expression of miR-218 in the dorsal spinal cord, in a pattern that closely overlaps with the formation of ectopic Hb9+ motor neurons (Fig. 2i, Supplementary Fig. 4b). These results suggest that miR-218 is expressed downstream of the Isl1-Lhx3 complex in the course of motor neuron differentiation.

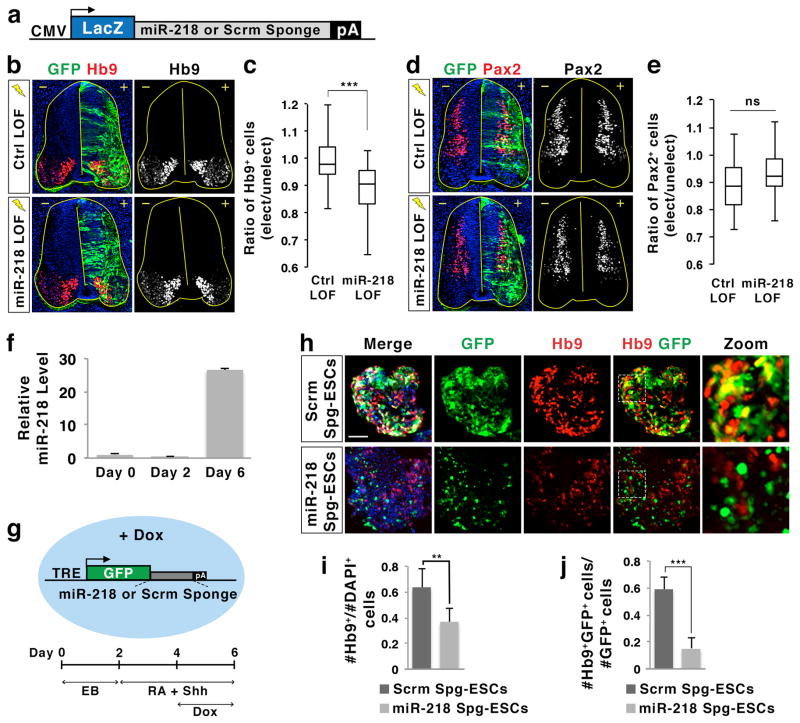

miR-218 is important for motor neuron fate specification

Next, to inhibit the action of endogenous miR-218, we designed miRNA bulge sponge inhibitors that function as stable and competitive miRNA inhibitors both in vitro and in vivo26,28. The miR-218 sponge inhibitor has multiple repeats of bulged miR-218 MRE sequences that are cloned into the 3′UTR of a CMV-promoter driven LacZ gene, whereas the control scrambled sponge has scrambled (scrm) bulge miR-218 MRE sequences (Fig. 3a). To enhance the inhibition of endogenous miR-218, we combined the miR-218 sponge inhibitor with 2′-O-methylated (2′Ome) antisense RNA inhibitors, which function as specific miRNA inhibitors29. Co-electroporation of the miR-218 sponge inhibitor with the 2′Ome-miR-218-inhibitor resulted in a significant 10% reduction of motor neuron generation in the developing spinal cord compared to the control condition (Fig. 3b, c). The miR-218 loss-of-function condition did not decrease the number of Pax2+ or Lhx1+ spinal interneurons or Olig2+ motor neuron progenitors (Fig. 3d, e, Supplementary Fig. 5a–d), suggesting that the inhibitory effect of miR-218 blockade is specific to motor neurons. In addition, there was no difference in the apoptotic cell death between miR-218 inhibition and control conditions, determined by immunohistochemical analyses with activated-Caspase3 antibody, indicating that the loss of motor neurons upon miR-218 inhibition is not due to increased cell death. Together, our data provide in vivo evidence that miR-218 plays an important role in the specification of motor neurons.

Figure 3. miR-218 is important for motor neuron differentiation.

(a) Illustration of bulge sponge inhibitor constructs, which have either bulged miR-218 MRE or control scrambled (Scrm) sequences in the 3′UTR of a CMV-promoter driven LacZ gene.

(b,d) Loss of function (LOF) analyses in chicks electroporated with control (Ctrl) LOF conditions (scrambled sponge inhibitor, 2′Ome-inhibitor control, and CMV-GFP) or miR-218 LOF conditions (miR-218 sponge inhibitor, miR-218 2′Ome-inhibitor, and CMV-GFP). Hb9 labels motor neurons, while Pax2 labels a broad population of interneurons in immunohistochemical analyses. +, electroporated side; −, unelectroporated control side.

(c,e) The effect of LOF conditions was quantified by the ratio of Hb9+ cells or Pax2+ cells on the electroporated (elect) side over the unelectroporated (unelect) control side. ***p < 0.0001 in two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant; n = 19–21 embryos for (b) Hb9 counts and n = 15–18 embryos for (d) Pax2 counts.

(f) The qPCR analysis using miR-218 TaqMan probe revealed that miR-218 expression is low in ESCs cultured in monolayer (day 0) or in embryoid bodies (day 2), but is highly induced in ESC-derived motor neurons (day 6). Error bars represent the standard deviation.

(g) Illustration of doxycycline (Dox)-inducible sponge mouse ESC lines, in which Dox induces the expression of either miR-218 sponge inhibitor or scrambled (Scrm) sponge inhibitor, and the experimental design to differentiate ESCs to motor neurons. TRE, tetracycline response element; EB, embryoid body; RA, retinoic acid; Shh, a sonic hedgehog agonist Purmorphamine.

(h) Immunohistochemical analyses in Dox-inducible sponge ESC-derived motor neurons cultured with Dox at differentiation day 6. Hb9 labels motor neurons, and GFP labels the cells, in which the expression of Scramble (Scrm) or miR-218 sponge inhibitor is induced by Dox. Zoom shows the magnified view of the areas marked by dotted lines in Hb9/GFP merged images. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

(i,j) The effect of Dox-inducible sponge inhibitors was quantified by the ratio of Hb9+ cells over all cells (DAPI+) (i), or by the ratio of Hb9 and GFP double-positive motor neurons over the total number of GFP+ cells (j). Error bars represent the standard deviation. **p < 0.001 and ***p < 0.0001 in two-tailed Student’s t-test. n = 15 embryoid bodies.

miR-218 is essential for motor neuron generation from ESCs

To further investigate whether miR-218 is important for motor neurogenesis, we sought a cellular context in which miR-218 might be inhibited more efficiently. ESCs differentiate into motor neurons when embryoid bodies are formed and treated with RA and a sonic hedgehog agonist30. We first monitored miR-218 levels in this motor neuron differentiation paradigm. The miR-218 level was low in ESCs and embryoid bodies, but miR-218 was upregulated ~27 fold when ESCs acquire motor neuron characteristics (Fig. 3f), consistent with the motor neuron-specific expression of miR-218 in the developing spinal cord (Fig. 2b, c).

To test whether robust upregulation of miR-218 is important for the specification of motor neuron fate, we generated a mouse ESC line, in which Dox induces the expression of miR-218 sponge inhibitor linked to the GFP gene, as well as a control ESC line that expresses scrambled sponge inhibitor in a Dox-dependent manner (Fig. 3g). The miR-218 sponge ESCs enabled us to control the precise timing of miR-218 inhibition when the endogenous miR-218 begins to be induced in newly born motor neurons by treating the cells with Dox. We drove motor neuron differentiation in miR-218 sponge and control ESCs in the presence or absence of Dox, and monitored the efficiency of motor neuron generation (Fig. 3h–j, Supplementary Fig. 5e). In the absence of Dox, both ESC lines exhibited effective motor neuron differentiation, as determined by the expression of motor neuron markers including Hb9 (Supplementary Fig. 5e). The miR-218 sponge inhibitor, which is induced by Dox in miR-218 sponge ESCs, strongly suppressed the generation of Hb9+ motor neurons, compared to the scrambled control inhibitor (Fig. 3h, i, Supplementary Fig. 5e). Furthermore, a majority of motor neurons produced under miR-218 inhibition condition lacked GFP expression (Fig. 3h, j), indicating that miR-218 sponge inhibitor-expressing cells are resistant to motor neuron differentiation.

Together, our data demonstrate that a high level of miR-218 activity at the onset of motor neurogenesis is critical for motor neuron specification.

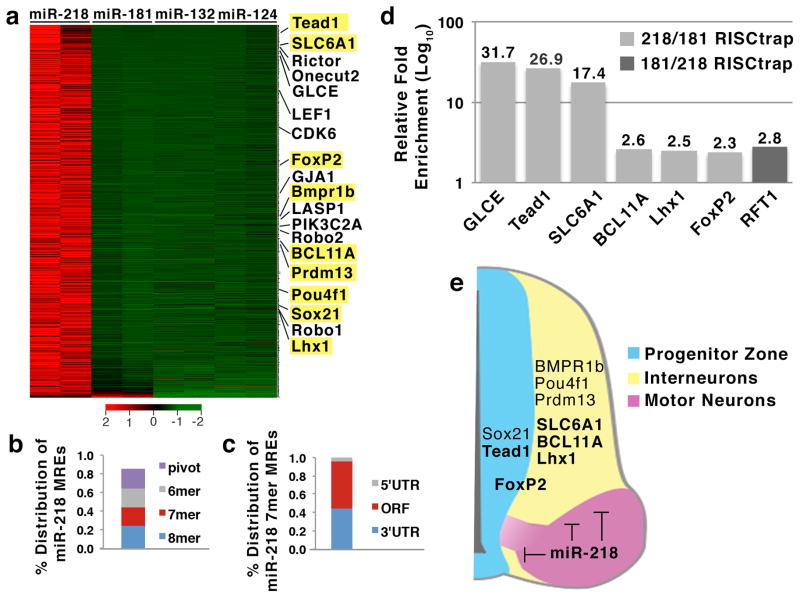

Identification of direct miR-218 target mRNAs

To understand the mechanisms by which miR-218 contributes to motor neurogenesis, it is important to determine miR-218 target mRNAs. To this end, we employed a RISC-trap assay, which effectively detects the interactions between a miRNA and its target transcripts, even when the target mRNAs are present at low abundance31. miRNAs regulate target mRNAs via a miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC), in which a mature miRNA directly binds to Argonaute that interacts with GW182, leading to destabilization of the mRNA transcripts (Supplementary Fig. 6a). We expressed miR-218 and a dominant negative form of Flag-tagged GW182 (Flag-dnGW182), which is incorporated into miRISC and stabilizes the RISC-miRNA-mRNA intereaction, in HEK293T cells. We then immunopurified RISC using anti-Flag antibodies and sequenced co-purified mRNAs on a HiSeq platform. To identify miR-218-specific target transcripts, the RISC-trap datasets for miR-218 were compared against previously generated RISC-trap datasets of three miRNAs, miR-181, miR-124 and miR-13231. This analysis revealed a high confidence list of 1178 target mRNAs, which satisfied the criteria for the significant enrichment in at least one pairwise comparison among RISC-trap datasets (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Data 2). Our list of miR-218 targets included previously identified miR-218 target transcripts, such as Rictor, CDK6, and GLCE (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 6b)32,33, validating our RISC-trap analyses. In addition, the list revealed many novel miR-218 target mRNAs with high fold enrichments (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Data 2).

Figure 4. Identification of direct miR-218 target mRNAs using RISC-trap screen.

(a) RISC-trap screens identified direct target genes for miR-218, when analyzed against RISC-trap screens for miR-181, miR-132, miR-12431. All identified miR-218 targets are sorted in a heatmap by fold-change and biological replicates, compared to miR-181 RISC-trap (FDR <0.05, fold enrichment ≥ 4). Previously published miR-218 targets identified in the RISC-trap screen are labeled, and selected miR-218 targets, which were newly identified by RISC-trap, are highlighted in yellow. Scale bar represents Z-score of row.

(b,c) Analyses for miR-218 MREs in 1178 genes targeted by miR-218. (b) Percent distribution of miR-218 MREs was classified by the inclusion of at least 1 MRE motif in the order of 8mer > 7mer > 6mer > pivot. Each transcript was counted only once. (c) Percent distribution of miR-218 7mer MRE motifs per target in the 5′UTR, ORF, and 3′UTR.

(d) Independent RISC-trap experiments followed by qRT-PCR analyses validated selected miR-218 target genes enriched against miR-181 RISC-trap. RFT1 is a miR-181 target mRNA identified in the RISC-trap screen. The qPCR results were shown as relative fold change in Log10 scale between miR-218 and miR-181 RISC-trap experiments.

(e) Schematic model of the expression patterns of selected RISC-trap miR-218 target mRNAs. These target mRNAs include genes that are important for the differentiation and function of spinal interneurons, such as Lhx1, BCL11A, SLC6A1, FoxP2, Pou4f1, Prdm13, Sox21, and Bmpr1b, as well as genes that play roles in spinal neural progenitors, including Tead1, FoxP2 and Sox21.

Direct MRE search analyses using our miR-218 target list from the RISC-trap revealed that the majority of targets contained miR-218 binding motifs (Fig. 4b). The RISC-trap target mRNAs contained an average of ~1.7 of 7mer miR-218 MREs per target and most MREs were located in both the 3′UTR and the open reading frame (ORF) (Fig. 4c). The equal distribution of miR-218 MREs in the 3′UTR and ORF suggest that de novo searches for miR-218 targets that utilize only 3′UTR sequence information may neglect potential targets with miR-218 MREs in the ORF. To assess the functional significance of the miR-218 target transcripts, we performed gene ontology (GO) term and cluster anlayses (Table 2, Supplementary Data 3). These analyses revealed that cell cycle and DNA stress response GO clusters were highly enriched for miR-218 targets, consistent with the previous reports that miR-218 functions as a tumor supressor miRNA33,34. Interestingly, the analyses also uncovered significant GO term clusters including transcription regulation and neuronal development related genes, suggesting that miR-218 targets identified via the RISC-trap contain a significant number of mRNAs that are relevant to neuronal differentiation and development.

Table 2. Gene ontology cluster analysis.

Biological process terms from selected significantly enriched clusters.

| Gene Ontology Analysis Term | % Genes | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription 3.65* | ||

| Regulation of transcription | 16.50 | 7.90E-04 |

| Transcription | 14.80 | 7.00E-06 |

| Transcription, DNA-dependent | 10.90 | 2.00E-02 |

| Cell Cycle 7.27* | ||

| Cell cycle | 8.10 | 9.50E-11 |

| Mitotic cell cycle | 4.30 | 1.00E-07 |

| Cell division | 3.90 | 1.70E-08 |

| DNA Stress Response 3.66* | ||

| Cellular response to stress | 5.00 | 9.40E-05 |

| DNA damage stimulus response | 4.00 | 4.70E-06 |

| DNA repair | 2.70 | 2.00E-03 |

| Neuron Development 2.09* | ||

| Cell projection organization | 3.50 | 3.50E-04 |

| Neuron differentiation | 3.50 | 7.70E-03 |

| Neuron development | 2.80 | 7.40E-03 |

GO Cluster score

miR-218 targets neural progenitor and interneuron mRNAs

A subset of miR-218 target genes from the RISC-trap screen are particularly relevant in the context of motor neuron development considering their expression pattern and previously reported functions in the developing spinal cord. These target mRNAs include genes that are important for the differentiation and function of spinal interneurons, such as Lhx1, BCL11A, SLC6A1, FoxP2, Pou4f1, Prdm13, Sox21, and Bmpr1b, as well as genes that play roles in spinal neural progenitors, including Tead1, FoxP2 and Sox21 (Fig. 4e, Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 7) 35–42. These genes are either weakly expressed in newly born motor neurons or are downregulated as progenitors differentiate into motor neurons (Supplementary Fig. 7). Thus, their expression pattern is roughly complementary with miR-218 expression during motor neurogenesis in the developing spinal cord, raising a possibility that miR-218 plays an important role to downregulate these non-motor neuron genes during motor neuron differentiation (Fig. 4e).

Table 3. Selected miR-218 RISC-trap target mRNAs.

RISC-trap fold change shows enrichment folds in miR-218 RISC-trap against RISC-trap screens with miR-181, miR-132, or miR-124. The number of miR-218 MRE shows the total number of miR-218 MRE in each gene from human, mouse and chicken. Note that for some genes, the full-length sequences of chicken gene are unavailable.

| miR-218 Target mRNA | RISC-trap Fold Change | # 218 MREs |

|---|---|---|

| Tead1 |

vs. miR-181: 37.3 vs. miR-132: 32.2 vs. miR-124: 14.5 |

Human - 10 Mouse - 7 *Chicken - 2 |

| SLC6A1 (GAT1) |

vs. miR-181: 18.3 vs. miR-132: 13.7 vs. miR-124: 17.9 |

Human - 4 Mouse - 4 *Chicken - 2 |

| BCL11A (Ctip1) |

vs. miR-181: 4.8 vs. miR-132: 6.8 vs. miR-124: 5.8 |

Human - 6 Mouse - 4 Chicken - 6 |

| Lhx1 |

vs. miR-181: 4.2 vs. miR-132: 4.9 vs. miR-124: 4.3 |

Human - 2 Mouse - 1 Chicken - 1 |

| FoxP2 |

vs. miR-181: 5.9 vs. miR-132: 4.9 vs. miR-124: 4.8 |

Human - 4 Mouse - 6 Chicken - 4 |

| Prdm13 |

vs. miR-181: 4.3 vs. miR-132: 5.9 vs. miR-124: 6.5 |

Human - 1 Mouse - 1 *Chicken: no seq |

| Sox21 |

vs. miR-181: 4.3 vs. miR-132: 5.9 vs. miR-124: 6.5 |

Human - 1 Mouse - 1 *Chicken: no seq |

| Pou4f1 |

vs. miR-181: 4.4 vs. miR-132: 4.8 vs. miR-124: 5.4 |

Human - 2 Mouse - 3 *Chicken: no seq |

| BMPR1b |

vs. miR-181: 5.2 vs. miR-132: 5.3 vs. miR-124: 4.8 |

Human - 2 Mouse - 2 *Chicken - 1 |

Only partial or provisional sequence available

The functional relevance and the presence of evolutionarily conserved miR-218 MREs on miR-218 target candidates led us to further validate five target mRNAs: Tead1, SLC6A1, BCL11A, Lhx1, and FoxP2. We performed independent RISC-trap experiments with miR-218 and miR-181 in HEK293T cells, and quantified the enrichment levels of the selected targets using qRT-PCR analyses (Fig. 4d). Tead1 and SLC6A1 were strongly enriched and BCL11A, Lhx1 and FoxP2 were also substantially enriched in the miR-218 RISC-trap samples, compared to the miR-181 RISC-trap samples (Fig. 4d). Conversely, RFT1, a miR-181 target mRNA identified in the RISC-trap screen, was enriched in miR-181 RISC-trap over miR-218 RISC-trap (Fig. 4d). This differential enrichment pattern of miRNA target transcripts in this RISC-trap assay was highly correlated with the RISC-trap datasets (Table 3).

Each of the Tead1, SLC6A1, BCL11A, Lhx1, and FoxP2 mRNAs has at least two putative miR-218 MREs in the 3′UTR region (Fig. 5a, Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 8). To test whether miR-218 regulates the expression of target transcripts via a miR-218 MRE, we constructed luciferase reporters, in which the 3′UTR region of each target containing one evolutionarily conserved miR-218 MRE is inserted between a luciferase gene and poly adenylation sequences (Fig. 5a–c). We then transfected luciferase reporters with either miR-218 or miR-181 in HEK293T cells, and monitored the luciferase expression levels. The expression of miR-218 led to significant repression in all five luciferase reporters linked with the 3′UTR of miR-218 targets, compared to miR-181 expression (Fig. 5c). The mutation in miR-218 MRE sequences within each luciferase reporter completely eliminated miR-218-dependent repression of the reporter activity (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 8f), indicating that a miR-218 MRE in the 3′UTR of target mRNAs triggers the miR-218-directed target gene suppression.

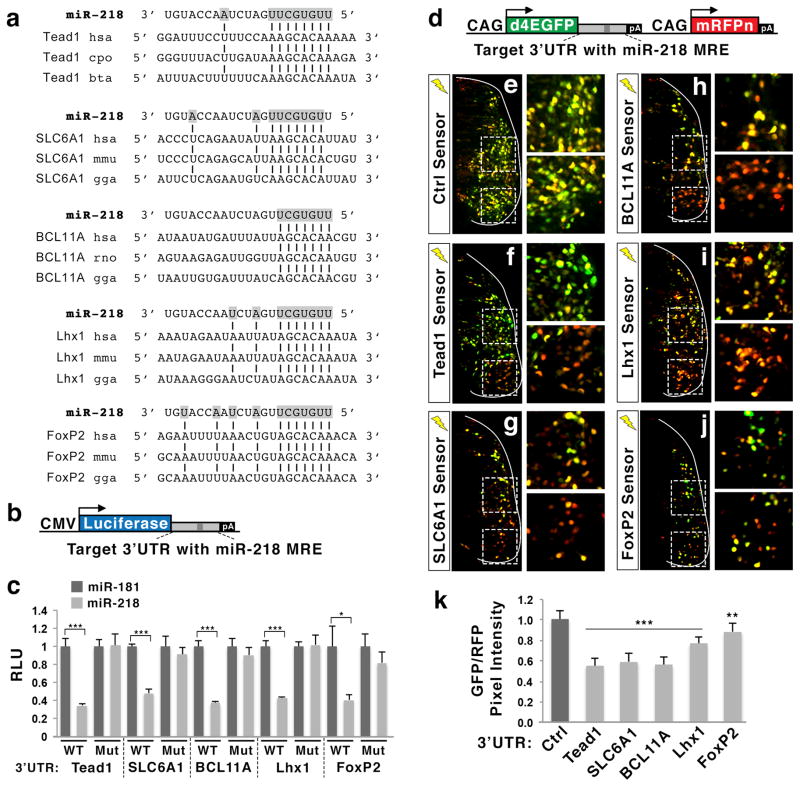

Figure 5. 3′UTR region of Tead1, SLC6A1, BCL11A, Lhx1 and FoxP2 mediates miR-218-directed gene repression via miR-218 MRE.

(a) Evolutionarily conserved miR-218 MREs in the 3′UTRs of selected RISC-trap target as identified by TargetScan.

(b) Illustration of miRNA luciferase reporter plasmids, in which the partial 3′UTR of miR-218 targets is cloned downstream of the luciferase gene.

(c) Luciferase assays using luciferase reporters linked with the 3′UTR of miR-218 targets in HEK293T cells. miR-218 inhibits the 3′UTRs in a miR-218 MRE-dependent manner. Each reporter was transfected with either miR-218 or miR-181. WT, luciferase reporters linked to the wild-type 3′UTR sequences of each gene; Mut, luciferase reporters linked to the mutated 3′UTR, in which miR-218 MRE is mutated to eliminate the binding of miR-218. RLU, relative luciferase unit. Error bars represent the standard deviation. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.0001 in two-tailed Student’s t-test. n = 3.

(d) Illustration of miRNA sensor plasmids, in which the partial 3′UTR of miR-218 targets is cloned downstream of d4EGFP. The expression of both d4EGFP and mononuclear RFP (mRFPn) is driven by two separate, ubiquitously active CAG promoters.

(e–j) The in vivo miRNA sensor analyses in the developing chick spinal cord electroporated with each miRNA sensor as indicated. Only the electroporated side of the spinal cord is shown. GFP expression is regulated by the 3′UTR of miR-218 target genes containing a miR-218 MRE, while RFP is ubiquitously expressed in all electroporated cells. Interneuron and motor neuron regions are magnified. The miRNA sensors show significant downregulation of GFP in motor neuron area compared to interneuron area.

(k) Quantification of relative pixel intensity of GFP/RFP in motor neurons, as quantified using ImageJ program. Error bars represent the standard deviation. ***p < 0.0001 and **p < 0.005 in two-tailed Student’s t-test. n = 6–8 embryos.

Together, our results suggest that miR-218 inhibits the expression of Tead1, SLC6A1, BCL11A, Lhx1, and FoxP2 by directly binding to their 3′UTR regions.

miR-218 represses target genes in motor neurons via 3′UTR

To test whether endogenous miR-218 in motor neurons downregulates each target mRNA via 3′UTR in vivo, we generated miRNA sensor plasmids in which the partial 3′UTR of Tead1, SLC6A1, BCL11A, Lhx1, or FoxP2 is cloned downstream of d4EGFP, and monitored the expression ratios of GFP and RFP in motor neurons and interneurons in the developing spinal cord three days after in ovo electroporation (Fig. 5d). The control miRNA sensor showed the same GFP/RFP ratio in interneurons and motor neurons (Fig. 5e, k). In contrast, the miRNA sensors with the 3′UTR of Tead1, SLC6A1, BCL11A, Lhx1, or FoxP2 transcripts showed varying degree of downregulation of GFP in motor neurons compared to interneurons. The 3′UTRs of Tead1, SLC6A1, and BCL11A directed ~ 45% downregulation of GFP in motor neurons, whereas the 3′UTRs of Lhx1 and FoxP2 led to 20% and 10% knockdown of GFP, respectively (Fig. 5f–k). These data suggest that endogenous miR-218 in developing motor neurons is capable of suppressing the expression of Tead1, SLC6A1, BCL11A, Lhx1, and FoxP2 via their 3′UTRs containing miR-218 MREs.

The partial 3′UTRs of each target gene were sufficient to respond to miR-218 in our luciferase and miRNA sensor analyses, showing that each miR-218 target transcript has at least one functional miR-218 binding site. However, it is notable that each of the selected miR-218 targets contains multiple 218 MREs throughout the gene body (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 8a–e). For example, the FoxP2 gene has three different miR-218 MREs in the 3′UTR, while the 3′UTR region that we tested contains only one miR-218 MRE. Thus, miR-218-directed suppression of the target genes in our reporter assays likely represents only a fraction of responsiveness of gene repression to miR-218 for each gene.

miR-218 suppresses interneuron differentiation

To test whether miR-218 is capable of suppressing spinal interneuron fate in the developing spinal cord, we misexpressed miR-218 in the dorsal spinal cord using in ovo electroporation of the miR-218 expression construct (Fig. 6a, b). miR-218 did not trigger ectopic generation of motor neurons in the dorsal neural tube (Fig. 6b, d), suggesting that miR-218 alone is not sufficient to drive motor neuron differentiation. However, miR-218 expression resulted in a substantial reduction of Lhx1+, Pax2+, or FoxP2+ interneurons, whereas it did not make a significant change in the number of Ngn2+ cells or Olig2+ motor neuron progenitors (Fig. 6c, d). These results are consistent with our finding that Lhx1 and FoxP2 are miR-218 targets. In addition, sequence analyses uncovered that Pax2 also has an evolutionarily conserved, strong miR-218 MRE in the 3′UTR (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b).

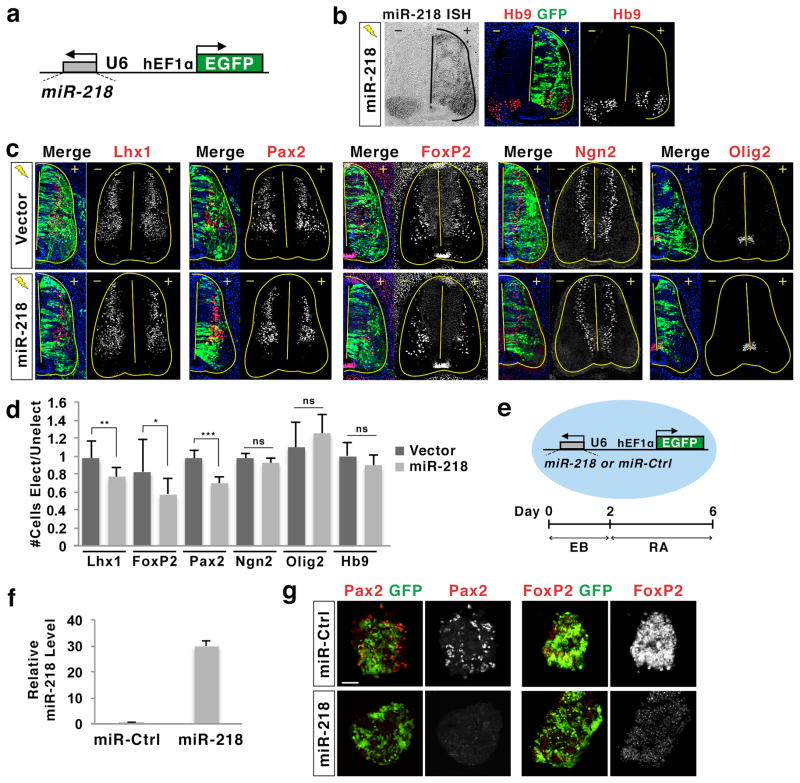

Figure 6. miR-218 represses differentiation of spinal interneurons.

(a) Illustration of miR-218 expression construct, in which the miR-218 sequence is cloned into the hairpin structure of the EFU6 shRNA plasmid. The expression of miR-218 is driven by the ubiquitously active U6 promoter, and the EGFP gene is regulated by a separate, ubiquitously active hEF1α promoter.

(b) Electroporation of the miR-218 construct results in robust and overlapping expression of miR-218 and GFP, as determined by in situ hybridization (ISH) with miR-218. miR-218 expression did not trigger ectopic formation of Hb9+ motor neurons. +, electroporated side; −, unelectroporated control side.

(c, d) Immunohistochemical analyses in chicks electroporated with miR-218 expression construct or vector. miR-218 expression led to the reduction of Lhx1+, Pax2+ and FoxP2+ interneurons, while it did not make a significant change in the number of Ngn2+ differentiating neurons, Olig2+ motor neuron progenitors, or Hb9+ motor neurons. +, electroporated (Elect) side; −, unelectroporated (Unelect) control side. ***p < 0.0001, **p < 0.001, and *p < 0.05 in two-tailed Student’s t-test. ns, not significant; n = 4–8 embryos.

(e) Illustration of miR-218 and miR-control (Ctrl) ESC lines, and the protocol to differentiate miRNA ESCs into Pax2+ and FoxP2+ spinal interneurons. In these ESCs, the expression of miR-218 or miR-Ctrl and EGFP are constitutively driven by U6 promoter and hEF1α promoter, respectively. EB, embryoid body; RA, retinoic acid.

(f) The miR-218 expression construct used to generate miR-218 ESCs triggers robust expression of miR-218 compared to the miR-Ctrl construct in HEK293T cells, as determined by qPCR analysis using miR-218 TaqMan probe.

(g) Immunohistochemical analyses of miRNA ESCs at interneuron differentiation day 6. miR-218 effectively inhibited the generation of Pax2+ and FoxP2+ interneurons. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

To further test the action of miR-218 in spinal interneuron differentiation, we generated ESC lines, in which either miR-218 or miR-control is constitutively expressed, and differentiated these ESCs to spinal interneurons by treating embryoid bodies with RA (Fig. 6e–g). In this condition, ESCs express spinal interneuron genes and acquire spinal interneuron characteristics13,30. miR-218 effectively blocked the expression of Pax2 and FoxP2, while the level of neuronal differentiation was comparable between miR-218 and miR-control ESCs as assessed by Tuj1 marker (Fig. 6g, Supplementary Fig. 9c). Similarly to the spinal cord, miR-218 was insufficient to trigger motor neuron generation (Supplementary Fig 9c).

Together, our data show that miR-218 serves as an efficient inhibitor of spinal interneuron differentiation, while miR-218 alone is incapable of inducing motor neuron fate.

miR-218 is needed for motor neuron generation by Isl1-Lhx3

Given our finding that miR-218 is upregulated by the Isl1-Lhx3 complex and directly targets a number of genes that control spinal interneuron differentiation, we hypothesized that miR-218 is a critical downstream effector of the Isl1-Lhx3 complex in suppressing non-motor neuron genes, thus ensuring the proper acquisition of motor neuron cell identity. To determine whether the Isl1-Lhx3 complex represses the differentiation of interneurons in vivo, we misexpressed Isl1-Lhx3 in the chick neural tube and monitored the differentiation of Pax2+ and Lhx1+ interneurons. Isl1-Lhx3 substantially suppressed the formation of Pax2+ and Lhx1+ interneurons in the developing spinal cord, compared to the unelectroporated control side (Fig. 7a–d), similar to its effect on interneuron genes in differentiating ESCs13. Notably, the ectopic miR-218/Hb9-expressing cells in the dorsal neural tube are mutually exclusive with Pax2+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 10), suggesting that Isl1-Lhx3 directs a complete fate transition from interneurons to motor neurons by strongly suppressing interneuron differentiation in the dorsal spinal cord. Next, to determine whether miR-218 is required for Isl1-Lhx3 to effectively trigger motor neuron differentiation, we electroporated Isl1-Lhx3 with either miR-218 sponge inhibitor or scrambled sponge control, and assessed the formation of ectopic motor neurons. Inhibition of miR-218 action suppressed Isl1-Lhx3-directed differentiation of motor neurons by ~ 50% (Fig. 7e, f), while significantly increasing the proportion of Lhx1-expressing cells among Isl1-Lhx3-electroporated cells (Supplementary Fig 11a, b). Likewise, the miR-218 sponge inhibitor reduced the efficiency of motor neuron production by the co-expression of Isl1 and Lhx3 by ~35% (Supplementary Fig. 11c, d). These results demonstrate that the activity of miR-218, which is induced by Isl1-Lhx3, is crucial for Isl1-Lhx3 to effectively suppress interneuron fate and to establish motor neuron identity.

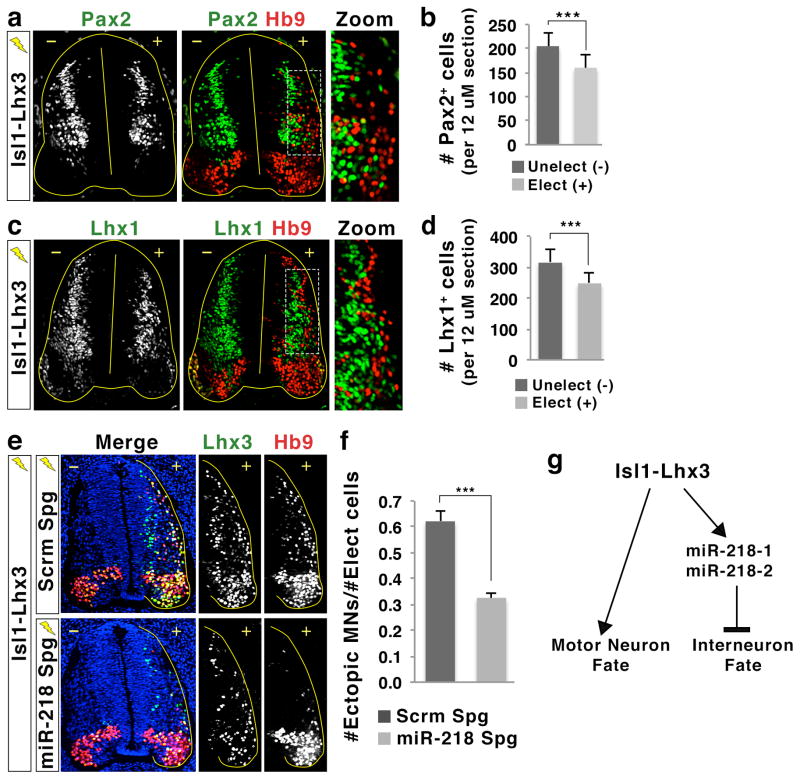

Figure 7. miR-218 is required for efficient generation of motor neurons by Isl1-Lhx3.

(a, c) Immunohistochemical analyses in the chick neural tube electroporated with Isl1-Lhx3. Isl1-Lhx3 suppresses the generation of Pax2+ or Lhx1+ interneurons, while promoting the formation of ectopic Hb9+ motor neurons in the dorsal spinal cord. The magnified images show that the Hb9+ motor neurons are largely exclusive with Pax2+ or Lhx1+ interneurons, suggesting that Isl1-Lhx3 drives motor neuron formation at the expense of interneurons. +, electroporated side; −, unelectroporated control side.

(b, d) Quantification of the number of Pax2+ or Lhx1+ interneurons on the electroporated (+) and unelectroporated (−) sides of the spinal cord. Isl1-Lhx3 expression resulted in a decrease in Pax2+ or Lhx1+ interneurons. Error bars represent the standard deviation. ***p < 0.0001 in two-tailed Student’s t-test. n = 3 embryos.

(e, f) The analyses of ectopic motor neuron formation by Isl1-Lhx3 in the presence of either miR-218 sponge inhibitor (miR-218 Spg) or scrambled sponge inhibitor (Scrm Spg) in the chick neural tube. +, electroporated side; −, unelectroporated control side. miR-218 inhibition reduces the efficiency of Isl1-Lhx3 in triggering ectopic motor neurons in dorsal neural tube. (f) The effect of miR-218 inhibition on Isl1-Lhx3-induced motor neuron differentiation was quantified by the ratio of ectopic Hb9+ motor neurons (MNs) over Lhx3-expressing transfected cells (Elect cells). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. ***p < 0.0001 in two-tailed Student’s t-test. n = 5 embryos.

(g) Model of the Isl1-Lhx3 and miR-218 gene regulatory network in motor neuron development. While triggering the expression of many motor neuron-specific genes required for motor neuron differentiation and maturation, Isl1-Lhx3 also directly induces the expression of miR-218-1 and miR-218-2, which are crucial to suppress unwanted interneuron genes in developing motor neurons.

DISCUSSION

During CNS development, neural progenitors undergo dramatic changes in gene expression to differentiate into diverse types of postmitotic neurons with distinct molecular and morphological phenotypes43. One of the fundamental challenges in development is to understand the molecular mechanisms that drive this drastic and thorough transformation of the gene expression profile as neural progenitors acquire a specific neuronal identity. In the last decade, there has been an increase in our understanding of the role of miRNAs in neuronal development, where miRNAs have been shown to be important regulators of neuronal differentiation in numerous model systems21,23,27,44,45. However, the role of miRNAs in directing the differentiation of distinct neuronal cell types remains ambiguous. Here we report that miR-218 acts as an essential regulator of motor neurogenesis as a direct downstream target of the Isl1-Lhx3 transcription complex (Fig. 7g).

Our comprehensive analyses of miR-218 expression, function and direct targets provide strong evidence that miR-218 plays a crucial role in motor neuron differentiation by repressing non-motor neuron fates (Fig. 7g). The generation of motor neuron progenitors (pMN), which give rise to motor neurons, has been attributed to the action of a sonic hedgehog morphogen gradient and the cross-repressive interactions between progenitor transcription factors, such as Olig2, Irx3 and Nkx2.21,2,6,46,47. However, pMN cells maintain plasticity in choosing their cell fates and have potential to generate non-motor neurons. Inactivation of Isl1, Hb9 or LMO4 in motor neurons leads to the aberrant upregulation of interneuron genes, and Olig2-lineage cells produce ventral interneurons in addition to motor neurons10,14,23,48,49. Thus, the mechanisms to suppress alternative cell fates need to operate continuously to block the erroneous gene expression during motor neuron differentiation. Our study demonstrates that miR-218 is induced during motor neurogenesis and plays an essential role to ensure the choice of motor neuron fate by suppressing interneuron genes. In addition, miR-218 is likely important to promote the timely transition of progenitor cells to postmitotic neurons by repressing target transcripts that promote neural progenitor characteristics. Interestingly, miR-218 does not appear to play an instructive role in motor neuron fate determination on its own, given that the misexpression of miR-218 alone is not sufficient to induce the formation of motor neurons in the spinal cord and differentiating ESCs. These results indicate that the activity of Isl1-Lhx3 to inhibit interneuron fate13 can be uncoupled from its activity to induce motor neuron generation. Our results also suggest that the miR-218-mediated action of Isl1-Lhx3 to suppress interneuron genes is important for Isl1-Lhx3 to efficiently trigger motor neuron differentiation. Together, our results support a model where miR-218, a downstream effector of Isl1-Lhx3, represses transcripts that promote interneuron and progenitor characteristics in differentiating motor neurons to ensure precise differentiation and the development of proper cellular phenotypes (Fig. 7g).

miR-218 expression is detected at the onset of motor neuron differentiation and the expression is maintained exclusively in motor neurons throughout embryonic spinal cord development. Thus, miR-218 is likely to have roles in mature motor neurons in addition to establishment of motor neuron fate. In this regard, it is interesting to note that many target transcripts identifed in the unbiased RISC-trap screen suggest a potential function for miR-218 in regulating neurite morphogenesis and synapse development. The miR-218 targets from our RISC-trap screen in this category include PTEN, NrCAM, CNTNAP2, EphA7, VCAN, MACF1, Clasp2, Robo1 and Robo2 (Dataset2 and Dataset3)50–58. Future research on the function of miR-218 in dendritogenesis, axogenesis and synaptogenesis of motor neurons may reveal crucial mechanisms in developing and maintaining proper motor neuron circuitry.

In addition to miR-218, our miRNA array study identified other miRNAs whose expression is significantly induced during Isl1-Lhx3-directed motor neuron differentiation (Table 1, Supplementary Data 1). Those upregulated miRNAs include three miRNAs that have been shown to play roles in reducing neural stem cell proliferation to stimulate neurogenesis: miR-26b, miR-200a, miR-22459–61. The co-expression of miRNAs in motor neurons raises the possibility that miR-218 functions in combination with other miRNAs, which are co-induced by Isl1-Lhx3, in controlling a subset of target genes. For example, miR-218 might cooperate with other miRNAs to repress genes that facilitate mitosis and proliferation. The combinatorial actions of miRNAs may be important for the selection or robust downregulation of targets that contain MREs for multiple miRNAs. This gene network consisting of Isl1-Lhx3 and multiple miRNAs during motor neuron development will provide an interesting platform to test the paradigm that a “transcription factor code” and “miRNA code” cooperate to direct the precise differentiation of neuronal subtypes62.

We also noted that several miRNAs implicated in neuronal development, such as miR-924,25,44,45 and miR-12421,22,27 are highly expressed in Isl1-Lhx3-ESC-derived motor neurons (Supplementary Data 1). miR-9 is an interesting candidate to cooperate with miR-218. miR-9 exhibits fluctuating spatiotemporal expression in the embryonic spinal cord, with a brief period of expression in a subset of postmitotic motor neurons24,25. In our miRNA array screen, the expression levels of miR-9 were high in both Dox-untreated and treated conditions, suggesting that miR-9 is not a direct target of the Isl1-Lhx3 complex. miR-9 is known to play multiple roles in CNS development, such as controlling the timing of neurogenesis, axon extension and branching, and regulates motor columnar formation25,44,45. While miR-218 expression was detected in all subtypes of motor neurons, it may control the differentiation of motor columns by collaborating with other miRNAs whose activity is specific to a motor neuron subtype. In light of this, it is notable that some of the miR-218 targets, such as Lhx1 and Onecut2, are known to have motor neuron subtype specific expression11,63. In the future, it will be interesting to further investigate the combinatorial actions of miRNA-218 with other miRNAs in motor neuron development.

In summary, our study provides important insights into how miRNAs contribute to the establishment of cell identity in CNS development and how they are interconnected with cell fate-determining transcription factors. The development of a unique cellular identity requires both activation and repression of genes, thereby building a gene expression profile that determines specific molecular and morphological characteristics. Our study suggests that employing miRNAs as downstream effectors of transcription activators to induce gene repression could be a prominent strategy in cell fate specification.

METHODS

DNA and RNA Constructs

Mammalian expression constructs for Isl1, Lhx3, Isl1-Lhx3, and GFP were previously described13. The generation of the miRNA sensor plasmid was previously described21. miRNA sensor MREs were cloned into the 3′UTR of sensor d4EGFP by multimerization of MRE-specific oligos that are listed in Supplementary Table 1. RISC-trap target miR-218 MRE containing 3′UTRs were amplified from HEK293T cell cDNA and two copies were cloned into the 3′UTR of sensor d4EGFP or luciferase reporter using primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. Target 3′UTR luciferase mutant reporters were generated using overlap extension PCR by combining the flanking primer sets and internal primers to mutate the miR-218 MREs. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Sponge inhibitor constructs were generated by multimerizing 10-repeated bulge sponge sequences that were ordered using GeneArt synthetic gene assembly (Life Technologies), followed by cloning these 40-repeats of sponge sequences into the 3′UTR of a CMV-LacZ reporter. The sequences ordered as synthetic genes are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The anti-2′Ome RNA constructs were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), oligo sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The miR-218 and miR-Control expression constructs were generated by annealing and cloning miR-218 or miR-Control sequences into the EFU6-300 hairpin vector, listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Isl1-Lhx3-ESC miRNA Array and Small RNA Quantitative RT-PCR

The generation and differentiation of Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs was previously described13,14. The miRNA microarray assays were performed with TaqMan® Array Rodent MicroRNA Card A (Life Technologies). The miRNA Array analyzes 380 miRNAs and contains five endogenous controls and one negative control assay. RNA extraction and cDNA amplification for TaqMan® miRNA array, miRNA and pri-miRNA assays were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions (http://www.lifetechnologies.com/us/en/website-overview/ab-welcome.html).

In Ovo Electroporation and Immunohistochemistry

In ovo electroporation was performed as described12. Briefly, constructs were injected into the lumen of the neural tube of HH stage 12 chick embryos, which were then electroporated. The embryos were harvested at HH stage 24–27, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and cryosectioned at 12 μm. Immunohistochemistry was performed using 0.1% Fish gelatin (Sigma) blocking buffer with overnight incubation at 4°C, using the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-Hb9/MNR2 (DSHB, 5C10; 1:300), rabbit anti-Pax2 (Life Technologies, Zymed 71-6000; 50% glycerol 1:500), rabbit anti-Lhx1/Lim1-211 (Homemade; 1:3000). rabbit anti-FoxP2 (Abcam, ab16046; 1:1000), rabbit anti-Lhx311 (Homemade; 1:2,000), rabbit anti-Olig213 (Homemade; 1:1000), rabbit anti-Ngn264,65 (Homemade; 1:5000), chicken anti-GFP (Aves Labs, GFP-1020; 1:2000), mouse anti-Tuj1 (Covance, MMS-435P, 1:2000). The n in quantification of chick electroporation data indicates the number of embryos included in the analyses. At least 2-6 sections per embryo were used for quantification. The methods used for statistical analyses are listed within each figure legend.

For the quantification of pixel intensity in miRNA sensor analyses, in ovo electroporation of miRNA sensor plasmids (1.2 μg/μl) was performed as described above. Unsaturated images were acquired on a Zeiss Axio Imager.Z2 microscope, maintaining the same exposure time ratio of GFP and RFP for each section. Pixel intensity was determined using ImageJ program (Supplementary Methods).

Luciferase Reporter Assays

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were plated in 48-well plate and incubated for 24 hr and transient transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). An actin-β-galactosidase plasmid was cotransfected for normalization of transfection efficiency and 20 nM of miRIDIAN microRNA mimics (Dharmacon) were used. Cells were harvested 24 hr after transfection. Cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity and the values were normalized with β-galactosidase activity, vector, and miR-181 treated reporter relative luciferase units. All transfections were repeated independently at least three times. Data are represented as the mean of triplicate values obtained from representative experiments. Error bars represent standard deviation.

In Situ Hybridization Assay

For in situ hybridization analysis, embryos were harvested at indicated stage, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, embedded in OCT, and cryosectioned at 18 μm. Locked nucleic acid (LNA)-modified miR-218 or miR-218* oligonucleotide probe (Exiqon) was labeled with digoxigenin according to the suppliers protocol (Roche) and use for in situ hybridization as described66.

RISC-trap, RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR

RISC-trap experiments and data analyses were performed as previously described, except that reads for each gene were counted by HTSeq (Simon.Huber.2013_HTSeq – A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data_BioRxiv002824)31. For independent miR-218 and miR-181 RISC-trap assays, transfections and immunoprecipitations were performed as previously described31 and Maxima H Minus (Thermo Scientific) used for reverse transcription. The levels of mRNA were determined with quantitative RT-PCR using SYBR-Green kit (Invitrogen) and Mx3000P (Stratagene).

Gene Ontology and MRE Analyses

The Gene Ontology (GO) functional analysis was carried out with the online tool DAVID using the default configurations67. For the MRE-directed search analyses, the 3′UTR, coding sequences (CDS), 5′UTR or the whole transcripts were directly searched by the miR-218 MREs, including 8mer (AAGCACAA), 7mer (AAGCACA), 6mer (AGCACA) and 7mer pivots (AAGgCACA or AAGcCACA).

Culture, Generation, and Differentiation of ESC lines

The A172LoxP ESC line was maintained in an undifferentiated state on 0.1% gelatin-coated dishes in the ESC growth media that consist of knockout DMEM, 10% FBS, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and recombinant leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (1,000 units/ml, Chemicon). GFP-miR-218 sponge inhibitor and GFP-scrambled sponge control inhibitor were cloned into Tet-inducible p2Lox plasmid. miR-218/GFP and miR-Control/GFP sequences were inserted into Tet-uninducible p2Lox vector. Then, these constructs were cotransfected with pSALK-Cre into A172LoxP ESCs by electroporation. Stable transfectant colonies were isolated by selection with neomycin (G418, 400 μg/ml) for 7 days. Dox-dependent induction of GFP-miR-218 sponge inhibitor or GFP-miR-scrambled sponge inhibitor was monitored by western blotting and immunohistochemical analyses using α-GFP antibody. For motor neuron differentiation assays, GFP-miR-218 sponge inhibitor and GFP-miR-scrambled sponge inhibitor ESCs were trypsinized and grown in the ESC growth medium without LIF in suspension as cell aggregates for 2 days. The ESC aggregates (embryoid bodies, EBs) were treated with all-trans RA (0.5 μM) and a Shh agonist Purmorphamine (1 μM, Calbiochem) for 2 days. Then, RA and Purmorphamine-treated EBs were cultured without or with Dox (2 μg/ml) in the presence of RA and Purmorphamine for another 2 days. For spinal neuronal differentiation of miR-218 and miR-Control ESCs, EBs were treated with all-trans RA (0.5 μM) for 4 days.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

ChIP was performed as described previously8,13,64,65 in Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs and mouse embryonic spinal cords. Isl1-Lhx3-ESCs were cultured on 0.1% gelatin-coated dishes in the ESC growth media lacking LIF in the presence or absence of Dox (2 μg/ml), which induces the expression of Flag-tagged Isl1-Lhx3, for 1 day. The spinal cords were microdissected from E12.5 mouse embryos and cells were dissociated and subjected to ChIP assays. Cells were washed with PBS buffer, fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, and quenched by 125 mM glycine. Cells were washed with Buffer I (0.25% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, pH 6.5) and Buffer II (200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Hepes, pH 6.5) sequentially. Then, cells were lysed with lysis buffer (0.5% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, protease inhibitor mixture) and were subjected to sonication for DNA shearing. Next, cell lysates were diluted 1:10 in ChIP buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, protease inhibitor mixture) and, for immunoclearing, were incubated with IgG and protein A agarose beads for 1 hr at 4°C. Supernatant was collected after quick spin and incubated with anti-Flag antibody (Sigma) and protein A agarose beads to precipitate Flag-Isl1-Lhx3/chromatin complex overnight at 4°C. After pull-down of Flag-Isl1-Lhx3/chromatin/antibody complex with protein A agarose beads, the beads were washed with TSE I (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl), TSE II (same components as in TSE I except 500 mM NaCl), and Buffer III (0.25 M LiCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0) sequentially for 10 min at each step. Then the beads were washed with Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer three times. Flag-Isl1-Lhx3/chromatin complexes were eluted in elution buffer (1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 M NaHCO3, 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0) and decrosslinked by incubating at 65°C overnight. Eluate was incubated at 50°C for more than 2 hr with Proteinase K. Next, DNA was purified with Phenol/chloroform and DNA pellet was precipitated by ethanol and resolved in water. Immunoprecipitation were performed using anti-IgG, anti-Isl1 and anti-Lhx3 antibodies for mouse embryonic spinal cord cells. The primers that were used for ChIP-seq analyses are listed in Supplementary Methods. All ChIP experiments were repeated independently at least two times. Data are represented as the mean of triplicate values obtained from representative experiments. Error bars represent standard deviation.

ChIP-seq Data Analysis

ChIP-seq datasets from previous publications17,19 were analyzed using MACS68. For the analysis of peak location, we collected gene annotation from the UCSC genome browser (mm9).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Fred H. Gage and Xinwei Cao for the miRNA sensor vector; to Dr. Greg Scott for creating the ImageJ GFP/RFP pixel intensity analysis script; to Younjung Park for the excellent technical support; to Lee laboratory members for discussions. This research was supported by grants from NIH/NINDS (R01 NS054941), the March of Dimes Foundation, and the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation (to S.-K. Lee), NIH/NIDDK (R01 DK064678) (to J. W. Lee), NIH/NIDDK (R01 DK103661) (to S.-K. Lee and J. W.L ee), NIH/NIMH (R01 MH094416) (to R. H. Goodman) and Basic Science Research Program (2012R1A1A1001749) and Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (2012M3A9C6050508) of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MEST) and National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (1220120), and Aspiring Researcher Program of Seoul National University in 2014 (to S. Lee).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.P.T. and S-K.L. conceived and designed the project. K.P.T. planned and performed most of the experiments. S.L., H.N., and H.C designed and performed ESC experiments in Fig. 1d–h, Fig. 3f–j, and Fig. 6e–g. X.A.C., R.S., and R.H.G. developed the RISC-trap assay and provided RISC-trap data. R.S. performed the bioinformatics analyses. S.M.G. provided preliminary miR-218 expression data. J.K. provided additional bioinformatics analyses. J.W.L. and S.L. provided advice and editing. S-K.L. supervised the study. K.P.T and S-K.L. wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jessell TM. Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:20–29. doi: 10.1038/35049541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SK, Pfaff SL. Transcriptional networks regulating neuronal identity in the developing spinal cord. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4 (Suppl):1183–1191. doi: 10.1038/nn750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helms AW, Johnson JE. Specification of dorsal spinal cord interneurons. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2003;13:42–49. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briscoe J, Pierani A, Jessell TM, Ericson J. A homeodomain protein code specifies progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell. 2000;101:435–445. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muhr J, Andersson E, Persson M, Jessell TM, Ericson J. Groucho-mediated transcriptional repression establishes progenitor cell pattern and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell. 2001;104:861–873. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novitch BG, Chen AI, Jessell TM. Coordinate regulation of motor neuron subtype identity and pan-neuronal properties by the bHLH repressor Olig2. Neuron. 2001;31:773–789. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SK, Pfaff SL. Synchronization of neurogenesis and motor neuron specification by direct coupling of bHLH and homeodomain transcription factors. Neuron. 2003;38:731–745. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshi K, Lee S, Lee B, Lee JW, Lee SK. LMO4 Controls the Balance between Excitatory and Inhibitory Spinal V2 Interneurons. Neuron. 2009;61:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma K, et al. LIM homeodomain factors Lhx3 and Lhx4 assign subtype identities for motor neurons. Cell. 1998;95:817–828. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81704-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thaler J, et al. Active suppression of interneuron programs within developing motor neurons revealed by analysis of homeodomain factor HB9. Neuron. 1999;23:675–687. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuchida T, et al. Topographic organization of embryonic motor neurons defined by expression of LIM homeobox genes. Cell. 1994;79:957–970. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thaler JP, Lee SK, Jurata LW, Gill GN, Pfaff SL. LIM factor Lhx3 contributes to the specification of motor neuron and interneuron identity through cell-type-specific protein-protein interactions. Cell. 2002;110:237–249. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S, et al. Fusion protein Isl1–Lhx3 specifies motor neuron fate by inducing motor neuron genes and concomitantly suppressing the interneuron programs. PNAS. 2012;109:3383–3388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114515109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, et al. A Regulatory Network to Segregate the Identity of Neuronal Subtypes. Developmental Cell. 2008;14:877–889. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hester ME, et al. Rapid and efficient generation of functional motor neurons from human pluripotent stem cells using gene delivered transcription factor codes. Molecular Therapy. 2011;19:1905–1912. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Son EY, et al. Conversion of mouse and human fibroblasts into functional spinal motor neurons. Stem Cell. 2011;9:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazzoni EO, et al. Synergistic binding of transcription factors to cell-specific enhancers programs motor neuron identity. Nature Neuroscience. 2013;16:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/nn.3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho HH, et al. Isl1 directly controls a cholinergic neuronal identity in the developing forebrain and spinal cord by forming cell type-specific complexes. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee S, et al. STAT3 promotes motor neuron differentiation by collaborating with motor neuron-specific LIM complex. PNAS. 2013;110:11445–11450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302676110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao X, Pfaff SL, Gage FH. A functional study of miR-124 in the developing neural tube. Genes & Development. 2007;21:531–536. doi: 10.1101/gad.1519207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visvanathan J, Lee S, Lee B, Lee JW, Lee SK. The microRNA miR-124 antagonizes the anti-neural REST/SCP1 pathway during embryonic CNS development. Genes & Development. 2007;21:744–749. doi: 10.1101/gad.1519107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen JA, et al. Mir-17-3p Controls Spinal Neural Progenitor Patterning by Regulating Olig2/Irx3 Cross-Repressive Loop. Neuron. 2011;69:721–735. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luxenhofer G, et al. MicroRNA-9 promotes the switch from early-born to late-born motor neuron populations by regulating Onecut transcription factor expression. Developmental Biology. 2014;386:358–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otaegi G, Pollock A, Hong J, Sun T. MicroRNA miR-9 Modifies Motor Neuron Columns by a Tuning Regulation of FoxP1 Levels in Developing Spinal Cords. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:809–818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4330-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otaegi G, Pollock A, Sun T. An Optimized Sponge for microRNA miR-9 Affects Spinal Motor Neuron Development in vivo. Front Neurosci. 2011;5:146. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoo AS, Staahl BT, Chen L, Crabtree GR. MicroRNA-mediated switching of chromatin-remodelling complexes in neural development. Nature. 2009;460:642–646. doi: 10.1038/nature08139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebert MS, Neilson JR, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: competitive inhibitors of small RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat Meth. 2007;4:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schratt GM, et al. A brain-specific microRNA regulates dendritic spine development. Nature. 2006;439:283–289. doi: 10.1038/nature04367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wichterle H, Lieberam I, Porter JA, Jessell TM. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into motor neurons. Cell. 2002;110:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cambronne XA, Shen R, Auer PL, Goodman RH. Capturing microRNA targets using an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC)-trap approach. PNAS. 2012;109:20473–20478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218887109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prudnikova TY, et al. miRNA-218 contributes to the regulation of D-glucuronyl C5-epimerase expression in normal and tumor breast tissues. epigenetics. 2012;7:1109–1114. doi: 10.4161/epi.22103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venkataraman S, et al. MicroRNA 218 Acts as a Tumor Suppressor by Targeting Multiple Cancer Phenotype-associated Genes in Medulloblastoma. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:1918–1928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tu Y, et al. MicroRNA-218 Inhibits Glioma Invasion, Migration, Proliferation, and Cancer Stem-like Cell Self-Renewal by Targeting the Polycomb Group Gene Bmi1. Cancer Research. 2013;73:6046–6055. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanotel J, et al. The Prdm13 histone methyltransferase encoding gene is a Ptf1a-Rbpj downstream target that suppresses glutamatergic and promotes GABAergic neuronal fate in the dorsal neural tube. Developmental Biology. 2014;386:340–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.John A, et al. Bcl11a is required for neuronal morphogenesis and sensory circuit formation in dorsal spinal cord development. Development. 2012;139:1831–1841. doi: 10.1242/dev.072850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pillai A, Mansouri A, Behringer R, Westphal H, Goulding M. Lhx1 and Lhx5 maintain the inhibitory-neurotransmitter status of interneurons in the dorsal spinal cord. Development. 2007;134:357–366. doi: 10.1242/dev.02717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rousso DL, et al. Foxp-Mediated Suppression of N-Cadherin Regulates Neuroepithelial Characterand Progenitor Maintenance in the CNS. Neuron. 2012;74:314–330. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandberg M, Källström M, Muhr J. Sox21 promotes the progression of vertebrate neurogenesis. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/nn1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wine-Lee L. Signaling through BMP type 1 receptors is required for development of interneuron cell types in the dorsal spinal cord. Development. 2004;131:5393–5403. doi: 10.1242/dev.01379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zou M, Li S, Klein WH, Xiang M. Brn3a/Pou4f1 regulates dorsal root ganglion sensory neuron specification and axonal projection into the spinal cord. Developmental Biology. 2012;364:114–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao X, Pfaff SL, Gage FH. YAP regulates neural progenitor cell number via the TEA domain transcription factor. Genes & Development. 2008;22:3320–3334. doi: 10.1101/gad.1726608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alaynick WA, Jessell TM, Pfaff SL. SnapShot: spinal cord development. Cell. 2011;146:178–178.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coolen M, Thieffry D, Drivenes Ø, Becker TS, Bally-Cuif L. miR-9 controls the timing of neurogenesis through the direct inhibition of antagonistic factors. Developmental Cell. 2012;22:1052–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dajas-Bailador F, et al. microRNA-9 regulates axon extension and branching by targeting Map1b in mouse cortical neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nn.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Briscoe J, et al. Homeobox gene Nkx2. 2 and specification of neuronal identity by graded Sonic hedgehog signalling. Nature. 1999;398:622–627. doi: 10.1038/19315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee SK. Olig2 and Ngn2 function in opposition to modulate gene expression in motor neuron progenitor cells. Genes & Development. 2005;19:282–294. doi: 10.1101/gad.1257105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arber S, et al. Requirement for the homeobox gene Hb9 in the consolidation of motor neuron identity. Neuron. 1999;23:659–674. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song AH, et al. A Selective Filter for Cytoplasmic Transport at the Axon Initial Segment. Cell. 2009;136:1148–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bai G, et al. Presenilin-dependent receptor processing is required for axon guidance. Cell. 2011;144:106–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long H, et al. Conserved roles for Slit and Robo proteins in midline commissural axon guidance. Neuron. 2004;42:213–223. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Araujo M, Piedra ME, Herrera MT, Ros MA, Nieto MA. The expression and regulation of chick EphA7 suggests roles in limb patterning and innervation. Development. 1998;125:4195–4204. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ashrafi S, et al. Neuronal Ig/Caspr recognition promotes the formation of axoaxonic synapses in mouse spinal cord. Neuron. 2014;81:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beffert U, et al. Microtubule plus-end tracking protein CLASP2 regulates neuronal polarity and synaptic function. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:13906–13916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2108-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duflocq A, Chareyre F, Giovannini M, Couraud F, Davenne M. Characterization of the axon initial segment (AIS) of motor neurons and identification of a para-AIS and a juxtapara-AIS, organized by protein 4.1B. BMC Biol. 2011;9:66. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goryunov D, He CZ, Lin CS, Leung CL, Liem RKH. Nervous-tissue-specific elimination of microtubule-actin crosslinking factor 1a results in multiple developmental defects in the mouse brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;44:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perrin FE, Rathjen FG, Stoeckli ET. Distinct subpopulations of sensory afferents require F11 or axonin-1 for growth to their target layers within the spinal cord of the chick. Neuron. 2001;30:707–723. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu Y, et al. Versican V1 isoform induces neuronal differentiation and promotes neurite outgrowth. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2004;15:2093–2104. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng C, et al. A Unilateral Negative Feedback Loop Between miR-200 microRNAs and Sox2/E2F3 Controls Neural Progenitor Cell-Cycle Exit and Differentiation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:13292–13308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2124-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]