Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess whether observed emotional frequency (the proportion of instances an emotion was observed) and intensity (the strength of an emotion when it was observed) uniquely predicted kindergartners’ (N = 301) internalizing and externalizing problems. Analyses were tested in a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework with data from multireporters (reports of problem behaviors from teachers and parents) and naturalistic observations of emotion in the fall semester. For observed positive emotion, both frequency and intensity negatively predicted parent- or teacher- reported internalizing symptoms. Anger frequency positively predicted parent- and teacher-reported externalizing symptoms, whereas anger intensity positively predicted parent- and teacher-reported externalizing and parent-reported internalizing symptoms. The findings support the importance of examining both aspects of emotion when predicting maladjustment.

Keywords: anger, externalizing, internalizing, positive emotion

Emotional expressivity has been associated with a range of socioemotional outcomes, including childhood maladjustment (Denham et al., 2012; Eisenberg et al., 1999). However, in most research, frequency and intensity of emotion have not been differentiated, although the distinction has theoretical and methodological significance (Fabes, Hanish, Martin, & Eisenberg, 2002). Frequency of emotion refers to how often a specific emotion is expressed, regardless of the strength that it is felt. In contrast, emotion intensity refers to the arousal level (usually as observed by others) of a specific emotion when it is present. For example, an individual may express only a few moments of anger, but these few instances may be high in arousal (intensity) outbursts, which is perhaps indicative of dysregulation and a propensity for aggression. In the present study, we tested whether intensity and frequency of anger or positive emotional expressivity provide unique prediction of aspects of child maladjustment. Understanding the nuances of emotional expression is critical to identifying emotional-behavioral patterns of maladjustment to inform basic mechanisms in the development of psychopathology.

There is reason to suggest that frequency and intensity are somewhat distinct aspects of emotion expression. Diener, Larsen, Levine, and Emmons (1985) found that among adults, average levels (intensity and frequency undistinguished) of self-reported positive and negative emotion were negatively correlated (only when intensity was controlled for; otherwise, they were not significantly correlated) whereas the intensities of positive and negative emotion were strongly and positively correlated. Similar patterns have been reported for children (Kim, Walden, Harris, Karrass, & Catron, 2007). In many questionnaires, emotion intensity and frequency are not typically differentiated, and it is unclear whether reporters are rating emotion dispositions, frequency, and/or intensity, yet emotional expression is a predictor of maladjustment across development (Denham et al., 2012; Eisenberg et al., 1999). Thus, a key goal of this study was to separate emotion frequency from intensity, and examine the unique and potentially differential prediction of kindergartners’ externalizing and internalizing problems by frequency and intensity of anger or positive emotion.

Emotion Expressivity, Externalizing, and Internalizing Problem Behaviors

Emotional expression is one foundation for externalizing and internalizing symptomatology. Depression, for example, is characterized by recurring and intense sadness; in children, depression and externalizing symptoms include irritable moods such as anger and frustration (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Furthermore, internalizing symptoms (with stronger effects for depression) have been characterized by an absence of self-reported positive affect (Clark & Watson, 1991; Lonigan, Phillips, & Hooe, 2003). To date, the research literature indicates that the associations of positive emotionality (usually undifferentiated in regard to intensity vs. frequency) to children’s internalizing or externalizing difficulties in nonclinical samples are typically nonsignificant (Eggum et al., 2012; Ghassabian et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2007) or negative (Dougherty, Klein, Durbin, Hayden, & Olino, 2010; Ghassabian et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2007; Stifter, Putnam, & Jahromi, 2008), but occasionally positive (when positive emotionality was characterized by exuberance; Putnam, 2012). Positive emotion also likely contributes to positive social interactions and competence (Jones, Eisenberg, Fabes, & MacKinnon, 2002; Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005). Thus, positive emotion frequency seemed likely to be associated with lower internalizing and externalizing problems, especially internalizing difficulties. Persons with intense positive emotion also seem unlikely to experience internalizing problems. However, because intense positive affect has been associated with impulsivity and low self-regulation (Kochanska, Aksan, Penney, & Doobay, 2007), positive emotion intensity might be inconsistently related to externalizing symptoms.

Mothers’ and teachers’ or self-reports of child negative emotion or anger (frequency and intensity often unspecified) have been positively related to internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Eggum et al., 2012; Eisenberg et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2007; Moran, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2013; Muris, Meesters, & Blijlevens, 2007). Similarly, observed frequency of anger reactions positively predicted later problem behavior (Eisenberg et al., 1999). Finally, children rated as high (vs. low) in negative emotional intensity exhibited sharper declines in social competence from kindergarten to third grade (Sallquist et al., 2009), as well as more problem behavior (Eisenberg et al., 1996). Thus, anger frequency and intensity were expected to predict more externalizing and internalizing problems, especially externalizing problems, but it was unclear whether frequency and intensity would provide unique prediction.

The Present Study

Researchers have seldom differentiated frequency from intensity of positive or negative emotion and examined their unique relations to maladjustment. Because we collected many observations of emotions that were rated for intensity, we could differentiate these two aspects of emotion and examine their unique relations to children’s maladjustment. We expected positive emotion frequency and intensity to both uniquely predict lower internalizing difficulties. Based on the literature, we were unsure if positive emotion frequency or intensity would predict externalizing symptoms. However, we expected anger emotion frequency and intensity to be associated with higher externalizing and internalizing behaviors, possibly with anger intensity being more predictive of externalizing difficulties.

Method

Participants

Participants were kindergarteners (N = 301, 52% girls, Mage = 5.5 years) from 26 classrooms in five schools recruited over 2 years (1 year apart). Fifty-three percent of children were Hispanic (34% non-Hispanic/white, 7% other, and 6% unknown). Mothers and fathers had varied education (30%, 39% ≤ high school degree, respectively; 31% and 24% some college; 39% and 37% college graduate) and household income (average = $50,000 to $69,999, range = ≤$9,999 to ≥$100,000).

Procedure

Data included teachers’ and parents’ ratings of children’s externalizing and internalizing symptoms and observations of children’s positive and anger emotions. Teachers received questionnaires for participating children early in the spring (95% response) and parents responded (in English or Spanish) in later autumn (79% response). Teachers and parents were paid for participation.

Measures

Externalizing and internalizing problems

Parents and teachers rated (1 = never/not true; 3 = often/very true), in late autumn and early spring, respectively, children’s externalizing and internalizing symptoms (Armstrong & Goldstein, 2003). Oppositional Defiant (nine items, αs = .81 [parent-reported], .89 [teacher-reported]) and Conduct Problems (10 items: αs = .82 [parent-reported], .84 [teacher-reported]) scales were significantly correlated (rs = .33, .30) and averaged across reporters. Depression (seven items, α = .66 [parent-reported]; six items, α = .82 [teacher-reported]) and Anxiety (eight items: αs = .66 [parent-reported], .78 [teacher-reported]) were rated on the same 3-point scale. Parents’ and teachers’ reports of anxiety had a low, nonsignificant correlation, and thus internalizing items were averaged within reporter.

Positive and anger emotion frequency and intensity

Observers scored children’s positive and anger emotions in classes, recess, and lunch in the fall semester, two to three times a week (approximately 9 to 12 weeks). Each child was observed by two or three different coders. Observers had a list and corresponding picture collage of participants for each class and rated (0 = no evidence; 3 = strong evidence) children’s positive (e.g., happiness, joy, excitement) and anger (e.g., anger, frustration) emotion after observing for 30 s (generally, children were not coded again until the entire list of present children was coded; Mtime-coded = 64 min, range = 16 to 133 min). There were eight cases that had a number of observations on the higher end (above 117 min); however, results in subsequent analyses remained the same with or without these eight cases. Prior to observing child interactions in participating schools, observers received several weeks of training, which included rating child interactions in pre-coded videos and/or in pilot preschool settings. Biweekly checks were made for agreement with the coding supervisor. Reliability ratings were obtained from a set of precoded videos (which were used for reliability purposes starting in the second year of the study) and randomly selected live scans, simultaneously rated by a second observer (Totaltime = 1,907 min) in the fall semester (intraclass correlation coefficient = .96 [positive], .88 [anger]).

For each child, emotional frequency was operationalized as the number of instances each emotion occurred, regardless of its intensity (a score of at least 1 [minimal evidence]) divided by the total number of scans per child for the given emotion (Mpositive-frequency = .41, range = .12 to .78; Manger-frequency = .02, range = .00 to .15; similar to Fabes et al., 2002). To assess emotion intensity, observers’ codes for a given child were averaged across all observations for each emotion with a score ≥ 1, when at least minimal emotion was observed (Mpositive-intensity = 2.25; Manger-intensity = 1.64).

Covariates

Covariates included age, ethnic minority status, sex, SES (standardized composite of family income and average parent education), and the percent of observations in classrooms versus other school settings.

Results

Correlations Among Study Variables

Positive emotion frequency and intensity were negatively correlated with teacher-reported depression (Table 1). Positive emotion intensity was negatively correlated with parent-reported depression and anxiety. Anger frequency and externalizing indicators were positively correlated.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Study Variables (N = 301)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | Min | Max | M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing Symptoms | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1. | Oppositional defiant disorder (PR, TR) | -- | 1.00 | 2.49 | 1.27 | 0.30 | |||||||||||||

| 2. | Conduct problems (PR, TR) | .72*** | -- | 1.00 | 2.22 | 1.10 | 0.19 | ||||||||||||

| Internalizing Symptoms | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. | Depression (TR) | .28*** | .26*** | -- | 1.00 | 2.67 | 1.23 | 0.36 | |||||||||||

| 4. | Anxiety (TR) | .11* | .07 | .52*** | -- | 1.00 | 2.63 | 1.32 | 0.33 | ||||||||||

| 5. | Depression (PR) | .39*** | .28*** | .30*** | .14** | -- | 1.00 | 2.29 | 1.20 | 0.25 | |||||||||

| 6. | Anxiety (PR) | .42*** | .25*** | .19*** | .11* | .68*** | -- | 1.00 | 2.75 | 1.36 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| Emotions in School | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. | Positive frequency (OB) | −.09 | −.08 | −.19*** | −.07 | −.08 | −.05 | -- | 0.12 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.11 | |||||||

| 8. | Positive intensity (OB) | −.08 | .00 | −.14** | −.05 | −.14** | −.14** | .23*** | -- | 1.30 | 2.88 | 2.25 | 0.26 | ||||||

| 9. | Anger frequency (OB) | .24*** | .18*** | .10* | .04 | −.01 | −.02 | −.01 | −.08 | -- | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||||

| 10. | Anger intensity (OB) | .10 | .04 | .02 | .01 | .06 | .12 | .01 | .33*** | .04 | -- | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.64 | 0.54 | ||||

| Covariates | |||||||||||||||||||

| 11. | SES | −.08 | −.14** | −.13** | −.12** | −.20*** | −.19*** | −.09 | −.02 | .00 | .10 | -- | −1.98 | 1.21 | −0.05 | 0.97 | |||

| 12. | Age | .04 | .00 | −.01 | −.04 | .00 | .06 | .05 | .04 | −.03 | −.05 | −.10* | -- | 4.27 | 6.81 | 5.48 | 0.35 | ||

| 13. | Ethnic Minority | −.05 | .05 | .17*** | .03 | −.02 | −.01 | .04 | −.06 | .03 | .02 | −.34*** | .10* | -- | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.48 | |

| 14. | Sex | .04 | −.01 | .08 | .06 | .01 | .00 | .07 | −.03 | −.03 | −.06 | .11* | .12** | −.07 | -- | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

Note. For Ethnic Minority category, Minority = 1; White, non-Hispanic = 0. For Sex category, Girl = 0; Boy = 1. Min = minimum; Max = maximum; PR = parent report; TR = teacher report; OB = observer report; SES = socioeconomic status (family income and average parent education).

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Preliminary Analyses: Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

We first evaluated the measurement properties of our study variables in a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014). To account for the clustering of data by classroom and missing data, we used the “Type=Complex” command and full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR).

The CFA for the latent variables showed good fit to the data: MLR χ2 (9) = 13.44, p >.10, comparative fit index (CFI) = .99, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .04, 90% CI [.00, .08]. Externalizing, composed of two indicators (i.e., composite scores of oppositional defiant and conduct problems across reporters; rs across reporters = .33 and .30, respectively), had significant standardized factor loadings (.92, .77). Internalizing, composed of two indicators (i.e., depression and anxiety), had significant standardized factor loadings for both the teacher-report construct (.91, .57) and the parent-report construct (.82, .83).

Structural Models

In the SEMs, covariates were correlated with one another and predicted emotion variables and outcomes. Tests of moderation showed that the models were equivalent across boys and girls and across ethnicity. Furthermore, cohort did not relate to the outcome study variables and, thus, we analyzed the proposed models with all participants in one group.

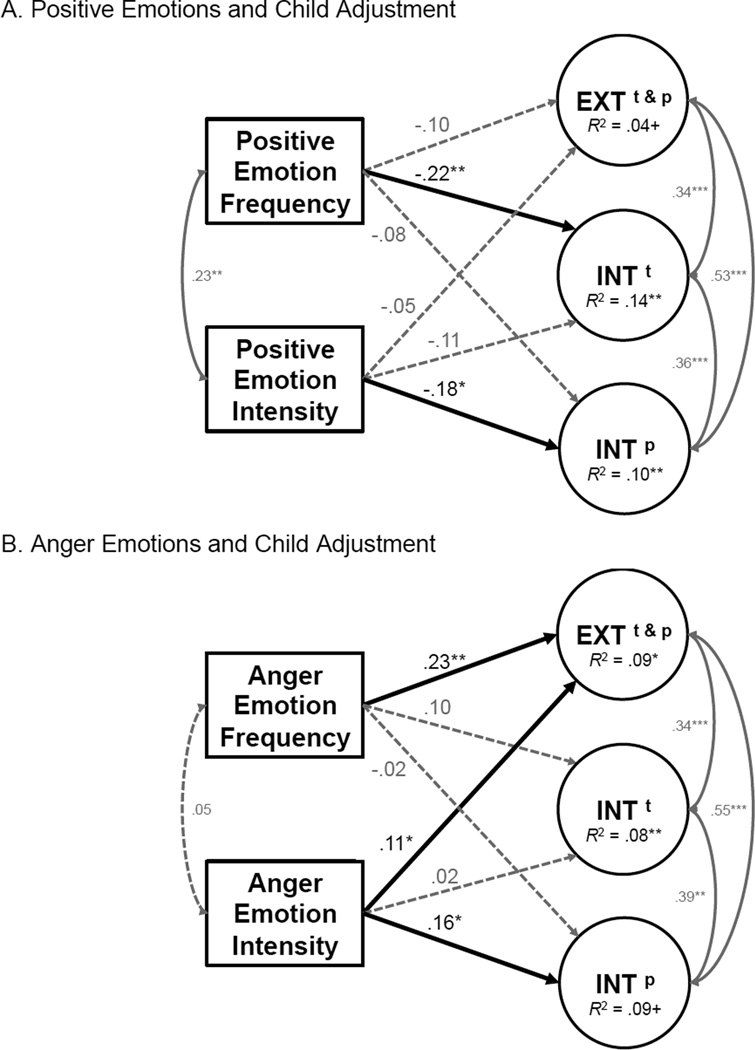

The model for positive emotion fit well (Figure 1a); positive emotion frequency and intensity both uniquely and significantly predicted lower internalizing (but not externalizing) symptoms. Although not shown, SES predicted lower externalizing and parent-reported internalizing (bs = −.15, −.26, ps < .05), ethnic minority status predicted lower parent-reported and higher teacher-reported internalizing (bs = −.12, .14, ps < .05), and boys had higher teacher-reported internalizing difficulties (b = .17, p < .01).

Figure 1.

SEM predicting child externalizing symptoms (EXT) reported by teachers and parents (EXTt & p) and internalizing symptoms (INT) reported by teachers (INTt) and parents (INTp). Standardized coefficients are presented. Dashed lines represent nonsignificant path coefficients. Covariates include age, ethnic minority status, sex, SES, and percent of classroom observations. Model A: MLR χ2 (30) = 36.20, p > .10, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03, 90% CI [.00, .05]. Model B: MLR χ2 (30) = 37.74, p > .10, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03, 90% CI [.00, .06]. +p < .05. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

In contrast, anger frequency was positively related to externalizing, but did not predict internalizing difficulties (Figure 1b). Anger intensity was positively related to externalizing and parent-reported, but not teacher-reported, internalizing problems. The covariates in this model had similar prediction patterns as the first model.

Discussion

The present study tested whether positive and anger emotion frequency and intensity predicted kindergartners’ maladjustment. Overall, the findings suggest that the frequency and intensity of emotions sometimes differentially and uniquely predict maladjustment, with more findings for intensity but slightly stronger effects for frequency.

Lyubomirsky et al. (2005) argued that it is the frequency, rather than the intensity, of positive affect that is a marker of happiness. Although we did not assess happiness per se, we found that frequency of positive affect expression was a predictor of lower teacher-reported internalizing difficulties. However, positive emotion intensity was negatively related to only parent-reported internalizing, suggesting that teachers and parents may be referencing different aspects of children’s positive affect to inform their reports of children’s internalizing problems. Our measures of emotion were observed only in the school context; perhaps frequency of positive emotionality at school, because it often is expressed with peers, differs from frequency of positive emotionality at home (where parents are present), or is associated with an increased likelihood of teachers’ viewing children’s positive emotion and/or parents may be more attuned to intensity of children’s emotion (because teachers must deal with many children and focus especially on disruptive emotions; Eisenberg et al., 1993). In addition, parents’ and teacher’ reports were assessed months apart; thus, positive emotion and anger intensity might have predicted parent- but not teacher-reported internalizing because of differences in timing of the reports, warranting further investigation.

The tripartite model of depression and anxiety suggests that lack of positive emotion characterizes depression but not anxiety (typically self-reported; Clark & Watson, 1991; Lonigan et al., 2003). In auxiliary analyses, we estimated and found that positive emotion intensity and frequency predicted depression and anxiety similarly; thus, we did not find support for the tripartite model. Our findings suggest that anxiety and depression were undistinguished, similar to research showing that they form a unitary internalizing construct rather than two separate constructs among younger children (Cole, Truglio, & Peeke, 1997). However, it is possible we did not find support for the model because we used adults’ reports of children’s depression and anxiety difficulties, for which it may be more difficult to distinguish depression from anxiety.

Neither positive emotion frequency nor intensity predicted externalizing symptoms. Children who show intense positive affect (exuberance, excitement) are prone to impulsivity and low self-regulation (Putnam, 2012). Thus, positive emotion intensity may not have predicted lower externalizing problems because intense positive emotion might be associated with low self-control and attention – qualities that are positively related to externalizing symptoms in some circumstances. Furthermore, we did not differentiate different aspects of positive emotion (e.g., awe, content) and perhaps positive emotions differ in their associations with externalizing symptoms.

Externalizing symptoms were uniquely predicted by observed intensity and frequency of anger, suggesting that attending to both provides better prediction of externalizing behaviors. In addition, consistent with some prior research (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2001; Muris et al., 2007) and diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), anger emotion intensity was positively related to parent-reported internalizing symptoms. Children who express intense anger may elicit rejection from peers and conflict with teachers that heighten internalizing symptoms. Anger more consistently predicted externalizing than internalizing difficulties, supporting research findings that anger and frustration accounts for more variance in externalizing than internalizing difficulties (e.g., Muris et al., 2007). Anger intensity may also be a common feature of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2001). Future research should assess emotion expression at home and school to examine emotion profiles and stability across settings, because this information could be informative regarding degrees of maladjustment risk. Future research should also examine emotion frequency and intensity in conjunction with emotion regulation in predicting externalizing symptoms, given previous research showing that negative emotion (typically undistinguished frequency and intensity) often predicts maladjustment particularly among children with low regulation (e.g., Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000; Moran et al., 2013).

Researchers previously have not typically distinguished emotion frequency from intensity (with very few exceptions) and examined how they uniquely relate to maladjustment. Emotion measures that examine both frequency and intensity may be capturing, to some extent, two different emotion profiles. Although further research is warranted, observed emotion intensity may reflect more salient, impactful, and lasting emotional experiences than emotion frequency (mild emotions may frequently be fleeting and/or emotional signals), which might explain why emotion intensity yielded one more significant prediction than emotion frequency. In any case, our findings suggest that the relations between positive emotion or anger and children’s maladjustment are more nuanced than is often credited.

Strengths of the study include extensive use of observational measures, as well as the use of multiple methods and reporters. Furthermore, measures of maladjustment were measured either after emotionality or toward the end of the assessment of emotion. Nonetheless, future research should consider bidirectional associations between emotional expression and various domains of maladjustment. In addition, relations of emotional intensity and frequency to adjustment might change with age (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005; Lengua, 2006); longitudinal research on these relations would clarify the generalizability of our results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01HD068522). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We thank the participating families, schools, staff, and research assistants who took part in this study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JM, Goldstein LH. Manual for the MacArthur health and behavior questionnaire (HBQ 1.0) MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Truglio R, Peeke L. Relation between symptoms of anxiety and depression in children: A multitrait-multimethod-multigroup assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:110–119. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Bassett HH, Thayer SK, Mincic MS, Sirotkin YS, Zinsser K. Observing preschoolers’ social-emotional behavior: Structure, foundations, and prediction of early school success. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2012;173:246–278. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2011.597457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Larsen RJ, Levine S, Emmons RA. Intensity and frequency: Dimensions underlying positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48:1253–1265. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Hayden EP, Olino TM. Temperamental positive and negative emotionality and children's depressive symptoms: A longitudinal prospective study from age three to age ten. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:462–488. [Google Scholar]

- Eggum ND, Eisenberg N, Reiser M, Spinrad TL, Michalik NM, Valiente C, Sallquist J. Relations over time among children's shyness, emotionality, and internalizing problems. Social Development. 2012;21:109–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children's externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Bernzweig J, Karbon M, Poulin R, Hanish L. The relations of emotionality and regulation to preschoolers' social skills and sociometric status. Child Development. 1993;64:1418–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Maszk P, Holmgren R, Suh K. The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC, Shepard S, Guthrie IK, Mazsk P, Jones S. Prediction of elementary school children's socially appropriate and problem behavior from anger reactions at age 4–6 years. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1999;20:119–142. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Losoya SH, Valiente C, Shepard SA. The relations of problem behavior status to children's negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:193–211. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Hanish LD, Martin CL, Eisenberg N. Young children's negative emotionality and social isolation: A latent growth curve analysis. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48:284–307. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassabian A, Szekely E, Herba CM, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Oldehinkel AJ, Tiemeier H. From positive emotionality to internalizing problems: The role of executive functioning in preschoolers. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;23:729–741. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0542-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, MacKinnon DP. Parents' reactions to elementary school children's negative emotions: Relations to social and emotional functioning at school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48:133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Walden T, Harris V, Karrass J, Catron T. Positive emotion, negative emotion, and emotion control in the externalizing problems of school-aged children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2007;37:221–239. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N, Penney SJ, Doobay AF. Early positive emotionality as a heterogeneous trait: Implications for children's self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:1054–1066. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ. Growth in temperament and parenting as predictors of adjustment during children's transition to adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:819–832. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM, Hooe ES. Relations of positive and negative affectivity to anxiety and depression in children: Evidence from a latent variable longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:465–481. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran LR, Lengua LJ, Zalewski M. The interaction between negative emotionality and effortful control in early social-emotional development. Social Development. 2013;22:340–362. doi: 10.1111/sode.12025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Blijlevens P. Self-reported reactive and regulative temperament in early adolescence: Relations to internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and "Big Three" personality factors. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP. Positive emotionality. In: Zentner M, Shiner RL, editors. Handbook of temperament. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sallquist JV, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Reiser M, Hofer C, Zhou Q, Eggum N. Positive and negative emotionality: Trajectories across six years and relations with social competence. Emotion. 2009;9:15–28. doi: 10.1037/a0013970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, Putnam S, Jahromi L. Exuberant and inhibited toddlers: Stability of temperament and risk for problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:401–421. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.