Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the relationship between self-perceived fatigue with different physical functioning tests and functional performance scales used for evaluating mobility-related disability among community-dwelling older persons.

Method:

This is a cross-sectional, population-based study. The sample was composed of older persons with 65 years of age or more living in Cuiabá, MT, and Barueri, SP, Brazil. The data for this study is from the FIBRA Network Study. The presence of self-perceived fatigue was assessed using self-reports based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living scale (IADL) and the advanced activities of daily living scale (AADL) were used to assess performance and participation restriction. The following physical functioning tests were used: five-step test (FST), the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), and usual gait speed (UGS). Three models of logistic regression analysis were conducted, and a significance level of α<0.05 was adopted.

Results:

The sample was composed of 776 older adults with a mean age (SD) of 71.9 (5.9) years, of whom the majority were women (74%). The prevalence of self-perceived fatigue within the participants was 20%. After adjusting for covariates, SPPB, UGS, IADL, and AADL remained associated with self-perceived fatigue in the final multivariate regression model.

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that there is an association between self-perceived fatigue and lower extremity function, usual gait speed and activity limitation and participation restriction in older adults. Further cohort studies are needed to investigate which physical performance measure may be able to predict the negative impact of fatigue in older adults.

Keywords: physical therapy, aging, functional capacity, fatigue

Introduction

Reports of fatigue are common in the older adult population1 , 2 and affect about 15-75% of community-dwelling older persons3 - 8, depending on the studied population. Fatigue is about twice as common in women and increases with age3 , 4, possibly reaching 70% among older persons 85 years of age and older9. Self-perceived fatigue is characterized as a subjective, conscious, and unpleasant symptom that involves the whole body and may be influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Under this perspective, a conscious report of tiredness is the most relevant information for fatigue evaluation2.

Self-perceived fatigue has a complex and multidimensional nature6. Different types of fatigue may coexist in the same person, thus hampering the identification of etiological factors. The most frequent types are mental fatigue, which may be subdivided into emotional and cognitive, and physical fatigue, which may be subdivided into sleepiness, low strength, and energy loss10. Studies highlight that there is a negative impact of self-perceived fatigue over mental and physical health and over functionality in older persons11 - 13.

Some studies have pointed out a substantial relationship between self-perceived fatigue, functional disability, and performance restriction in activities of daily living11 , 13. Older persons that reported fatigue presented less handgrip strength, slower walking speed, and poorer physical functionality of the lower limbs, even after comorbidity adjustment11. Ultimately, fatigue can be considered a complex health condition and it is associated with many domains of functionality among older adults, such as those related to body structure and function, activity limitation, and participation restriction, which encompass the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework (ICF)14.

Despite observed association between fatigue and physical function, the majority of studies have been carried out with older adults that have specific health states or diseases, such as older persons in pulmonary rehabilitation15 or suffering from cancer16or cardiac issues17. Besides, very few investigations addressed the magnitude of this association between fatigue in a comprehensive approach using physical functioning capacity and performance instruments among older persons living in the community. Therefore, a cross-sectional study was performed to investigate the relationship between self-perceived fatigue and different physical functioning tests and functional performance scales commonly used for evaluating mobility-related disability among community-dwelling older persons.

Method

This is a cross-sectional, population-based study conducted in two Brazilian cities with similar human development indexes in the FIBRA Network Study (Frailty in Brazilian Older Adults). Households were enrolled according to population density and to the number of community-dwelling older adults living in the census areas. Participants were evaluated from March 2009 to April 2010.

People were excluded if they: presented cognitive impairment assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination and adjusted by schooling18; had a permanent or temporary walking disability (canes and walkers were permitted, but not wheelchairs); presented a severe stroke or Parkinson's disease or terminal illness; or had a severe hearing and vision impairment hindering communication.

Study participants were evaluated in two phases. The first one consisted of face-to-face semi-structured interviews using a multidimensional questionnaire in a single session held by a trained health care professional, lasting 40 to 120 minutes. The second one consisted of a physical and functional data collection, lasting 20 to 30 minutes and using a battery of ten physical tests and anthropometric data, performed by physical therapists at public schools, community centers, and healthcare centers next to the older adults' residences.

All subjects signed an Informed Consent Form approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil under research protocol number 269/2007 for the FIBRA study in Barueri and by the Research Ethics Committee of Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto (HC/FMRP), Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil under protocol number 5018/2007 for the FIBRA study in Cuiabá, MT, Brazil.

The presence of self-perceived fatigue was evaluated using self-reports based on two questions from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale(CES-D)19. Participants answered questions regarding their fatigue experience in the two previous weeks: "Did you feel that you had to make an effort to cope with your activities of daily living?" and "Did you leave many of your interests and activities behind?" Possible answers were "never/rarely, a few times, mostly, always." Those who reported "mostly" and "always" in one of the questions were considered to have self-perceived fatigue11.

To characterize the sample, sociodemographic variables and physical/mental health conditions were investigated. Regarding physical and mental health variables, the following characteristics were evaluated: number of diseases diagnosed by a doctor within the last year and reported by the participants from a list (heart disease, lung disease, high blood pressure, stroke, diabetes, depression, malignant tumor), number of medications of continuous use taken within the last 3 months, falls within the last year, presence of health problems within the last year (urinary incontinence, falls, memory issues, trouble sleeping). The presence of depression was evaluated by the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15)20 and participants who presented five or more depressive symptoms were considered to have a positive screening for depression. Excessive sleepiness was evaluated using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (cutoff >11 points)21. Self-rated health was evaluated by asking the older adults how they perceived their own health in general (very good, good, regular, poor or very poor); the ones who answered "poor" or "very poor" were considered to have a poor health perception. Physical activity level was evaluated using the Minnesota Leisure Times Activities Questionnaire (MLTPA-Q)22 , 23. Older persons whose energy expenditure was inferior to 450 mets/week were considered to be sedentary24.

In order to investigate the association between fatigue and functional performance, we used the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale25. Social participation was measured using the advanced activities of daily living scale26. The physical-functioning tests conducted were: the Five-Step test27, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)28, and usual gait speed29.

The Five-Step Test measures the time (in seconds) it takes for the participant to go up and down a 10.1 cm wooden platform five times in a row. A cut-off point of 21 seconds was used27. Usual gait speed was measured from the time taken to walk a 4.6 meters long path, having 2 meters for acceleration and another 2 for deceleration. The test was carried out three times and the average was used. A cut-off point of 1.0 m/s was used.

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)28assesses the overall functionality of the lower limbs and consists of three parts: body stability balance test, usual gait speed, and the sit-to-stand test. Scores range from zero (worst performance) to 12 points (best performance). A cut-off point of 7 points or less was used30.

Comparison of older adults with and without fatigue regarding sociodemographics and clinical variables was carried out using the Chi-Square or Fisher's Exact tests. To compare both groups in terms of physical functioning capacity and functional performance, the T test or Mann-Whitney test was used, according to the adherence to normal distribution. Three models of logistic regression analysis were conducted in order to investigate the magnitude of association among fatigue and physical functioning capacity, functional performance, and social participation. Model 1 shows the crude logistic regression analysis. Model 2 was adjusted for the following covariates: number of diseases, memory difficulty, urinary incontinence, physical inactivity, and daytime excessive sleepiness. Model 3 was adjusted for covariates included in Model 2 plus arthritis, osteoporosis, hypertension, and depressive symptoms. The odds of presenting fatigue with confidence intervals of 95% (CI 95%) and p values were reported for each model. The adopted significance level was α<0.05. Statistical analyses were made using the program SPSS(r), version 19.0 or Windows.

Results

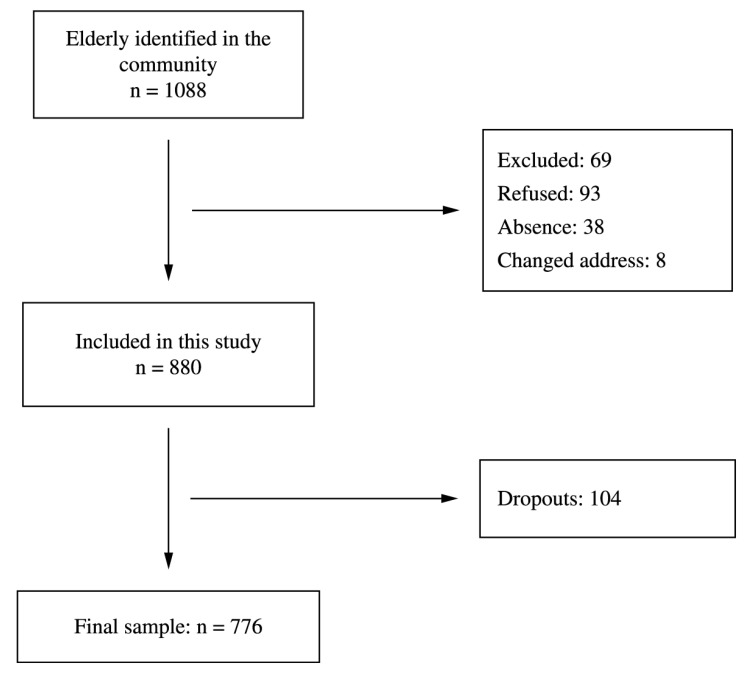

As shown in Figure 1, 776 older persons took part in this study, 391 of whom were from Cuiabá and 385 from Barueri. The mean age (SD) was 71.9 (5.9) years and from all participants 64% were women and 50% rated their health as poor. The prevalence of fatigue within the participants was 20.1%. The comparison between fatigued and non-fatigued older persons, according to sociodemographic variables, diseases, health conditions, depression, and sedentarism is shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Flow chart of study participants.

Table 1. Sociodemographics and clinical characteristics among non-fatigued and fatigued community-dwelling older adults, FIBRA study (n=776).

| Characteristics | Total Population n=776 | Non fatigued n=621 | Fatigued n=155 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female Sex | 497 (64.0) | 381 (62.2) | 116 (71.2) | 0.035 |

| 75 years old and over | 225 (29.0) | 173 (28.2) | 52 (31.9) | 0.382 |

| Schooling (0-4 years) | 577 (74.4) | 448 (73.1) | 129 (79.1) | 0.130 |

| Income (0-1 MW)* | 411 (54.7) | 316 (53.5) | 95 (59.4) | 0.210 |

| Diseases (≥4) | 153 (19.8) | 93 (15.2) | 60 (37.0) | <0.001 |

| Medication (≥4) | 220 (28.4) | 171 (27.9) | 49 (30.1) | 0.625 |

| Arthritis | 239 (30.8) | 164 (26.8) | 75 (46.0) | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 209 (26.9) | 155 (25.3) | 54 (23.1) | 0.047 |

| Hypertension | 521 (67.1) | 393 (64.1) | 128 (78.5) | <0.001 |

| Falls | 300 (38.7) | 217 (35.4) | 83 (50.9) | <0.001 |

| Memory problems | 381 (49.2) | 289 (47.2) | 92 (56.4) | 0.042 |

| Sleeping problems | 333 (43.0) | 260 (42.6) | 73 (44.8) | 0.656 |

| Excessive sleepiness | 162 (20.9) | 116 (18.9) | 46 (28.2) | 0.012 |

| Poor self-rated health | 393 (50.6) | 289 (47.1) | 104 (63.8) | <0.001 |

| Urinary incontinence | 157 (20.3) | 110 (17.9) | 47 (29.0) | 0.003 |

| GDS** | 194 (25.0) | 108 (17.6) | 86 (52.8) | <0.001 |

| Sedentary< 450 Mets | 199 (25.9) | 145 (24.0) | 54 (33.1) | 0.021 |

MW-Minimum Wage R$ 465.00 (four hundred and sixty five Reais) a month according to Law 11.944 of 200931.

GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale.

Older persons who reported fatigue had a poorer performance in physical-functioning tests and a greater restriction in advanced and instrumental activities of daily living when compared to non-fatigued older persons (Table 2). After adjusting for covariates, the SPPB, the usual gait speed and the advanced and instrumental activities of daily living remained significantly associated with fatigue in the final model (Table 3).

Table 2. Physical functioning limitation and participation restriction among non-fatigued and fatigued community-dwelling older adults. FIBRA study (n=776).

| Total Population n=776 | Non-fatigued n=621 | Fatigued n=155 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPPB <7 | 145 (18.7) | 98 (16.0) | 47 (28.8) | <0.001 |

| SPPB. median (IQI) | 10.0 (3.0) | 10.0 (3.0) | 9.0 (3.0) | <0.001‡ |

| UGS< 1m/s | 341 (44.0) | 235 (38.3) | 106 (65.4) | <0.001 |

| UGS. mean (SD) | 1.04 (0.29) | 1.07 (0.29) | 0.89 (0.26) | <0.001* |

| Five-step test >21s | 309 (39.9) | 222 (36.2) | 87 (53.7) | <0.001 |

| Five-step test. mean (SD) | 16.2 (6.2) | 15.7 (5.9) | 18.4 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| AADL >5 | 393 (50.7) | 350 (57.2) | 43 (26.4) | <0.001 |

| AADL. median (IQI) | 5.0 (5.0) | 5.0 (4.0) | 8.0 (5.0) | <0.001‡ |

| IADL >0 | 464 (59.8) | 406 (66.2) | 58 (35.6) | <0.001 |

| IADL. median (IQI) | 0.0 (2.0) | 0.0 (1.0) | 2.0 (4.0) | <0.001‡ |

SPPB: Short Physical Performance Battery; GS: Gait Speed; AAVD: Advanced Activity Daily Living; IADL: Instrumental Activity Daily Living.

Mann-Whitney test.

Student's t test.

Table 3. Multivariate models for the association of mobility-related disability measures and self-perceived fatigue among community-dwelling older adults. FIBRA study (n=776).

| Variables | OR | Model 1 | OR | Model 2 | OR | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95%-CI | p value | 95%-CI | p value | 95%-CI | p value | ||||

| SPPB <7 | 2.12 | 1.42-3.18 | <0.001 | 1.73 | 1.13-2.65 | 0.011 | 1.58 | 1.02-2.47 | 0.041 |

| UGS <1 m/s | 3.04 | 2.11-4.37 | <0.001 | 2.62 | 1.79-3.83 | <0.001 | 2.44 | 1.65-3.61 | <0.001 |

| Step Test >21 s | 1.98 | 1.28-3.09 | 0.002 | 1.44 | 0.89-2.32 | 0.133 | 1.44 | 0.87-2.39 | 0.150 |

| AADL >5 | 3.72 | 2.54-5.47 | <0.001 | 3.52 | 2.37-5.23 | <0.001 | 2.93 | 1.95-4.41 | <0.001 |

| IADL >0 | 3.55 | 2.47-5.09 | <0.001 | 3.06 | 2.10-4.46 | <0.001 | 2.53 | 1.71-3.73 | <0.001 |

SPPB: Short Physical Performance Battery; GS: Gait Speed; AADL: Advanced Activity Daily Living; IADL: Instrumental Activity Daily Living. Model 1: univariate analysis; Model 2: adjusted for covariates: number of diseases. memory difficulty. urinary incontinence. physical inactivity and daytime excessive sleepiness; Model 3: adjusted for covariates in Model 2 plus arthritis. osteoporosis. hypertension and depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The present study analyzed the prevalence of self-perceived fatigue and its association with physical-functioning capacity, functional performance, and participation restriction among a representative sample of community-dwelling older persons. We observed an independent relationship between self-perceived fatigue and the functionality of lower limbs, assessed by the SPPB, and usual gait speed. In addition, fatigue was also associated independently with functional performance and activity restriction identified by the older person's ability to perform instrumental and advanced activities of daily living. These associations remained significant even after the regression model was adjusted for covariates such as the number of comorbidities, the presence of diseases, specific health conditions, and depressive symptoms.

The negative effects of fatigue may contribute to a vicious cycle of low functionality with severe limitations in psychomotor skills, thus raising the risk of progressive physical functioning decline and activity restriction in older people. From this perspective, the assessment of physical-functioning tests may demonstrate more adequately the negative impact of fatigue on older people's health than considering only the presence of specific diseases32 , 33.

Fatigue in older adults can be classified into physical fatigue and mental fatigue10. It is common for older persons to experience more than one kind of fatigue and for conditions that relate to physical fatigue (muscle weakness, sleep disorders, and a low level of energy) and mental fatigue (depressed humor and poor focus) to interact concentrically and not in a linear fashion, ultimately demonstrating the multifactorial nature of fatigue within this population10 , 33.

Clinical evaluation, when performed properly, is a stage that optimizes eldercare. Choosing an evaluation instrument that accomplishes the main complaint is crucial for treatment planning, especially in a service with excessive patient turnover and absence of state-of-the-art technology. Physical functioning tests are objective measures that reflect functional limitations, whilst self-reported measures of functional performance may bring some bias related to gender and cultural differences, leading some authors to consider that functional capacity tests might predict disability more accurately than self-reported questionnaires. This leads to a wide acceptance of the use of physical-functioning tests to evaluate the functionality level of older people14. On the other hand, today there is also a relevant discussion towards the concept that disability should be considered an umbrella concept that includes the involvement of people in daily life situations and that the environment should be considered an important contextual factor that may influence how disability is experienced by the individual32.

Our results reveal that despite the adjustment for important covariates, there is a significant relationship between the SPPB, usual gait speed, and self-perceived fatigue. The SPPB has been recommended as an instrument to evaluate functional ability in older persons, essentially physical functionality of the lower limbs, and it is capable of predicting future functional decay29 , 30. SPPB comprises three dimensions: balance in static position, usual gait speed, and lower limb strength to sit down and rise from a chair. Muscle weakness in the lower limbs is frequently associated with physical fatigue and has an impact on the ability to generate isometric muscle contraction to maintain posture in a static position, which may negatively affect the performance in SPPB balance tests. Besides that, muscle weakness in the lower limbs may directly impair the ability to perform the test of sitting down and rising from a chair. It has been observed that there is a relationship between self-perceived fatigue and peak torque13, which represents the individual's maximum muscle strength, demonstrating the highest muscle performance level in the isokinetic test. A plausible explanation for this relationship may be the increased use of the oxidation pathway during muscle contraction and strength generation to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP)13 , 34.

Gait speed is described in the literature as a powerful predictor of survival, disability, hospitalization or institutionalization, dementia, and falls35. A substantial relationship between usual gait speed and self-perceived fatigue has been observed in this study. Although gait speed is a test that is also included in the SPPB, our results showed that the performance in the walking speed test alone presented a more significant relationship with fatigue. A plausible explanation for this would be that fatigued older persons would self-select their walking speed accordingly with their perception of functional reserve35. In addition, a decline in peak torque during muscle contraction was proved to negatively affect the walking speed34 , 35. The ability to maintain a steady position for only 10 seconds, a task that is also assessed in SPPB, is possibly less affected by the negative perception of being fatigued. However, the sit to stand task demands energy expenditure and the perception of being fatigued might influence this test. An explanation would be that the composite effect of the three tests would less influenced by perceived fatigue than the gait speed test alone.

Our study design restrains the use of gait speed and SPPB as predictors of disability due to fatigue. For physical therapists involved in clinical practice, it is important to observe that older people with fatigue may show a poor performance in these measures. Consequently, a further evaluation of its implications should be conducted among this population.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that there is an association between self-perceived fatigue and lower extremity function, usual gait speed and activity limitation and participation restriction in older adults. Further cohort studies are needed to investigate which physical performance measure may be able to predict the negative impact of fatigue in older adults.

Acknowledgments

We thank NAFIMES - Physical Capability, Computer Science, Metabolism, Sport and Health Center from Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso (UFMT), Cuiabá, MT, Brazil for the contribution in collecting data. The present study was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) through MCTCNPq/MS-SCTIE-DECIT notice number 17/2006, process number 555078/2006-0, and through FAPEMAT notice number 002/2007.

References

- 1.Schur E, Afari N, Goldberg J, Buchwald D, Sullivan PF. Twin analyses of fatigue. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10(5):729–733. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.5.729. http://dx.doi.org/10.1375/twin.10.5.729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahsberg E. Dimensions of fatigue in different working populations. Scand J Psychol. 2000;41(3):231–241. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vestergaard S, Nayfield SG, Patel KV, Eldadah B, Cesari M, Ferrucci L. Fatigue in a representative population of older persons and its association with functional impairment, functional limitation, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(1):76–82. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gln017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreh E, Jacobs JM, Stessman J. Fatigue, function, and mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(8):887–895. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq064. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glq064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong WS, Fielding R. Prevalence of chronic fatigue among Chinese adults in Hong Kong: a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1-3):248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander NB, Taffet GE, Horne FM, Eldadah BA, Ferrucci L, Nayfield S. Bedside-to-Bench conference: research agenda for idiopathic fatigue and aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(5):967–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02811.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02811.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avlund K. Fatigue in older adults: an early indicator of the aging process? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2010;22(2):100–115. doi: 10.1007/BF03324782. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03324782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy SE, Studenski SA. Fatigue and function over 3 years among older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(12):1389–1392. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.12.1389. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/63.12.1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avlund K, Schultz-Larsen K, Davidsen M. Tiredness in daily activities at age 70 as a predictor of mortality during the next 10 years. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(4):323–333. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00296-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00296-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy SE, Studenski SA. Qualities of fatigue and associated chronic conditions among older adults. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(6):1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vestergaard S, Nayfield SG, Patel KV, Eldadah B, Cesari M, Ferrucci L. Fatigue in a representative population of older persons and its association with functional impairment, functional limitation, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(1):76–82. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gln017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds KJ, Vernon SD, Bouchery E, Reeves WC. The economic impact of chronic fatigue syndrome. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2004;2(1):4–4. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-2-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-2-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva JP, Pereira DS, Coelho FM, Lustosa LP, Dias JMD, Pereira LSM. Clinical, functional and inflammatory factors associated with muscle fatigue and self-perceived fatigue in elderly community-dwelling women. Braz J Phys Ther. 2011;15(3):241–248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-35552011000300011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization - WHO . International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong CJ, Goodridge D, Marciniuk DD, Rennie D. Fatigue in patients with COPD participating in a pulmonary rehabilitation program. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:319–326. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S12321. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S12321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Pain, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling adults with and without a history of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32(2):118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.01.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreh E, Jacobs JM, Stessman J. Fatigue, function, and mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(8):887–895. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq064. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glq064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertolucci PHF, Brucki SMD, Campacci SR, Juliano YO. Mini-Exame do Estado Mental em uma população geral: impacto da escolaridade. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1994;52(1):1–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0004-282X1994000100001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batistoni SS, Neri AL, Cupertino AP. Validade da escala de depressão do Center for Epidemiological Studies entre idosos brasileiros. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41(4):598–605. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102007000400014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102007000400014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paradela EM, Lourenço RA, Veras RP. Validação da escala de depressão geriátrica em um ambulatório geral. Rev Saude Publica. 2005;39(6):918–923. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102005000600008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102005000600008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, Pedro VD, Menna Barreto SS, Johns MW. Portuguese-language version of the Epworth sleepiness scale: validation for use in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35(9):877–883. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132009000900009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132009000900009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor HL, Jacobs DR Jr, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31(12):741–755. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lustosa LP, Pereira DS, Dias RC, Britto RR, Parentoni AN, Pereira LSM. Tradução e adaptação transcultural do Minnesota Leisure Time Activities Questionnaire em idosos. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2011;5(2):57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR Jr, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(1):71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reuben DB, Laliberte L, Hiris J, Mor V. A hierarchical exercise scale to measure function at the Advanced Activities of Daily Living (AADL) level. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(8):855–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb05699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy MA, Olson SL, Protas EJ, Oberby AR. Screening for falls in community-dwelling elderly. J Aging Phys Act. 2003;11:66–80. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakano MM. Versão Brasileira da Short Physical Performance Battery - SPPB: adaptação cultural e estudo de confiabilidade [dissertação] Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW, Nicklas BJ, Simonsick EM, Newman AB. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people-results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1675–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasunilashorn S, Coppin AK, Patel KV, Lauretani F, Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S. Use of the Short Physical Performance Battery Score to predict loss of ability to walk 400 meters: analysis from the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(2):223–229. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gln022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brasil . Lei nº 11.944, de 28 de maio de 2009. Dispõe sobre o salário mínimo a partir de 1º de fevereiro de 2009. Diário Oficial da União; Brasília: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bean JF, Kiely DK, Herman S, Leveille SG, Mizer K, Frontera WR. The relationship between leg power and physical performance in mobility-limited older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):461–467. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50111.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Studenski S. Bradypedia: is gait speed ready for clinical use? J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(10):878–880. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0245-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12603-009-0245-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]