Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper was to undertake a review of literature on trigeminocardiac reflex in oral and maxillofacial online data-base and discuss the pathophysiology, risk factor assessment, presentation of the reflex, prevention, management with emphasis on the role of the attending anaesthetist and the maxillofacial surgeon.

Materials and Methods

The available literature relevant to oral and maxillofacial surgery in online data-base of the United States National Library of Medicine: Pubmed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) was searched. The inclusion criterion was to review published clinical papers, abstracts and evidence based reviews on trigeminocardiac reflex relevant to oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Results

Sixty-five articles were found with the search term "trigeminocardiac reflex" in the literature searched. Eighteen articles met the inclusion criteria for this study. The relevant data was extracted, tabulated and reviewed to draw evidence based conclusions for the management of trigeminocardiac reflex.

Conclusions

Conclusions were drawn and discussed based on the reviewed maxillofacial literature with emphasis on the anaesthetist’s and the surgeon’s role in the management of this detrimental event in maxillofacial surgical practice.

Keywords: Trigeminocardiac reflex, Oculocardiac reflex, Maxillofacial surgery, Vagus induced bradycardia, Bradycardia, Achener phenomenon, Trigemino-vagal reflex

Introduction

Stimulation of the trigeminal nerve sets off an arc inducing a cardiac depressor response via vagal stimulation. This could be a detrimental event in maxillofacial surgical practice both for the anaesthetist and the surgeon. Trigeminal nerve is the largest of the cranial nerves, and it provides sensory supply to the face, scalp, and mucosa of the nose and mouth [1]. Any surgical intervention in the distribution of trigeminal nerve poses a risk of precipitating trigeminocardiac reflex. This paper reviews literature on trigeminocardiac reflex in oral and maxillofacial online pubmed data-base and discusses the patho-physiology, risk factor assessment, presentation of the reflex, prevention, management with emphasis on the role of the attending anaesthetist and the maxillofacial surgeon.

Materials and Methods

A systematic search of the literature was carried out to identify eligible articles. The investigators searched the literature using the term ‘‘trigeminocardiac reflex’’ in the online databases of the United States National Library of Medicine: Pubmed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), accessed on Dec 2012. The only inclusion criterion was to review published reports, abstracts and studies with clinical cases and evidence based reviews on trigeminocardiac reflex occurring with maxillo-mandibular surgical procedures and facial trauma. The reports on neurosurgical and ENT procedures have been excluded. As this study included only the online database search and review of published data, it was exempt from Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) approval.

Results

Sixty-five articles were found with the search terms “trigeminocardiac reflex” in the online Pubmed database. Eighteen out of 65 articles met the inclusion criteria for this study. The relevant data was extracted and tabulated. (Table 1). Conclusions were drawn and discussed based on the reviewed maxillofacial literature with emphasis on the anaesthetist’s and the surgeon’s role in the management of this detrimental event in maxillofacial surgical practice.

Table 1.

Literature searched in the pubmed data-base for articles on trigeminocardiac reflex in maxillofacial literature

| Sl. No | Author(s) | Years | Comments (surgical procedure, facial injury etc.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lang et al. [8] | 1991 | Three patients, Maxillofacial surgery which did not include any manipulation of orbital structures |

| 2 | Roberts et al. [5] | 1999 | Temporomandibular joint arthroscopy in a 29-year-old white woman |

| 3 | Lynch and Parker [27] | 2000 | Bilateral penetrating ocular injuries |

| 4 | Yilmaz et al. [28] | 2006 | Trigeminocardiac reflex developed 48 h after orbital trauma due to intraorbital metallic foreign body in a 17-year-old male patient |

| 5 | Schaller and Buchfelder [29] | 2006 | Delayed trigeminocardiac reflex induced by an intraorbital foreign body |

| 6 | Webb and Unkel [30] | 2007 | Reflection of a palatal flap for removal of a mesiodens in a 5-year-old white girl |

| 7 | Bohluli et al. [15] | 2009 | Maxillofacial review on trigeminocardiac reflex |

| 8 | Arakeri and Arali [31] | 2010 | Hypothesis : trigeminocardiac reflex during extraction of teeth |

| 9 | Lübbers et al. [10] | 2010 | Repositioning of the zygoma, manipulations at the optic nerve. Authors have presented a review of records in University Hospital in Zurich between 2003 and 2008 |

| 10 | Bohluli et al. [32] | 2010 | Le Fort I osteotomy. Authors conducted a case-crossover study which included 25 Le Fort I osteotomy candidates |

| 11 | Arakeri and Brennan [33] | 2010 | Trigeminocardiac reflex as a potential risk factor for syncope in exodontia |

| 12 | Krishnan [34] | 2011 | Recommendation on use of suitable regional nerve blocks to prevent trigeminocardiac reflex in maxillofacial surgery |

| 13 | Bohluli et al. [35] | 2011 | Trigeminocardiac reflex, bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy, Gow-Gates block: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Study included 20 candidates for bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy |

| 14 | Puri et al. [36] | 2011 | TCR in Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma embolization |

| 15 | Potti et al. [37] | 2011 | TCR in percutaneous injection of ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx) into a juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma |

| 16 | Yorgancilar et al. [38] | 2012 | Rhinoplasty. TCR was detected in 8.3 % study patients following lateral osteotomies and nasal pyramid in fracture procedures. |

| 17 | Wartak et al. [39] | 2012 | Facial injury in a 56-year-old healthy male |

| 18 | Schames et al. [40] | 2012 | Sleep bruxism as a cause for trigeminal cardiac reflex |

Discussion

The trigeminocardiac reflex is reflexive response of bradycardia, hypotension, and gastric hypermotility induced with mechanical stimulation in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve [2]. Kumada et al. [3] were the first to describe the reflex bradycardia through their neurostimulation experiments on rabbits. Surgical manipulation of the eye causing cardiac dysrhythmia is well documented in ophthalmology literature [4]. Bernard Aschner and Guiseppe Dagnini in 1908 described pressure-induced neural reflex causing cardiac depression through vagal stimulation and the phenomenon was labelled oculocardiac reflex [5]. Currently, it is well known that reflex bradycardia, hypotension, apnea, and increased gastric motility may be induced with manipulation or stimulation of any of the peripheral branches or the central component of the trigeminal nerve [6]. Shelly and Church [7] introduced the nomenclature ‘trigeminocardiac reflex’.

Pathophysiology

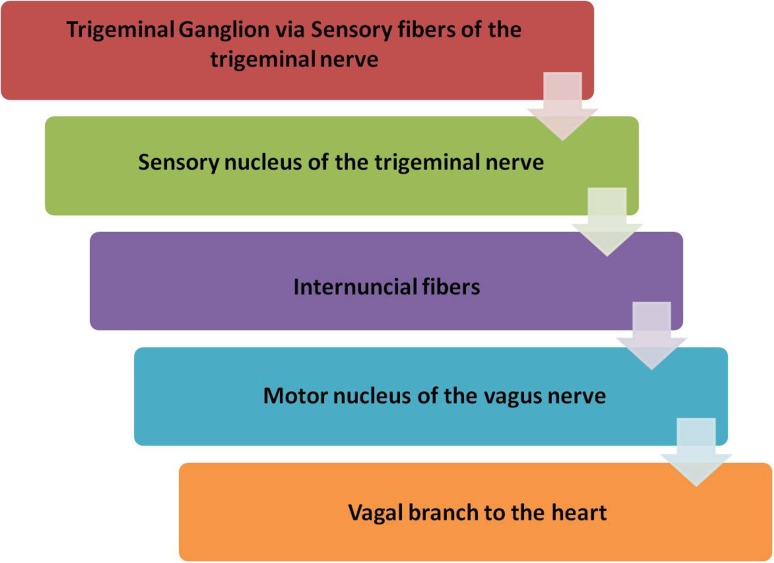

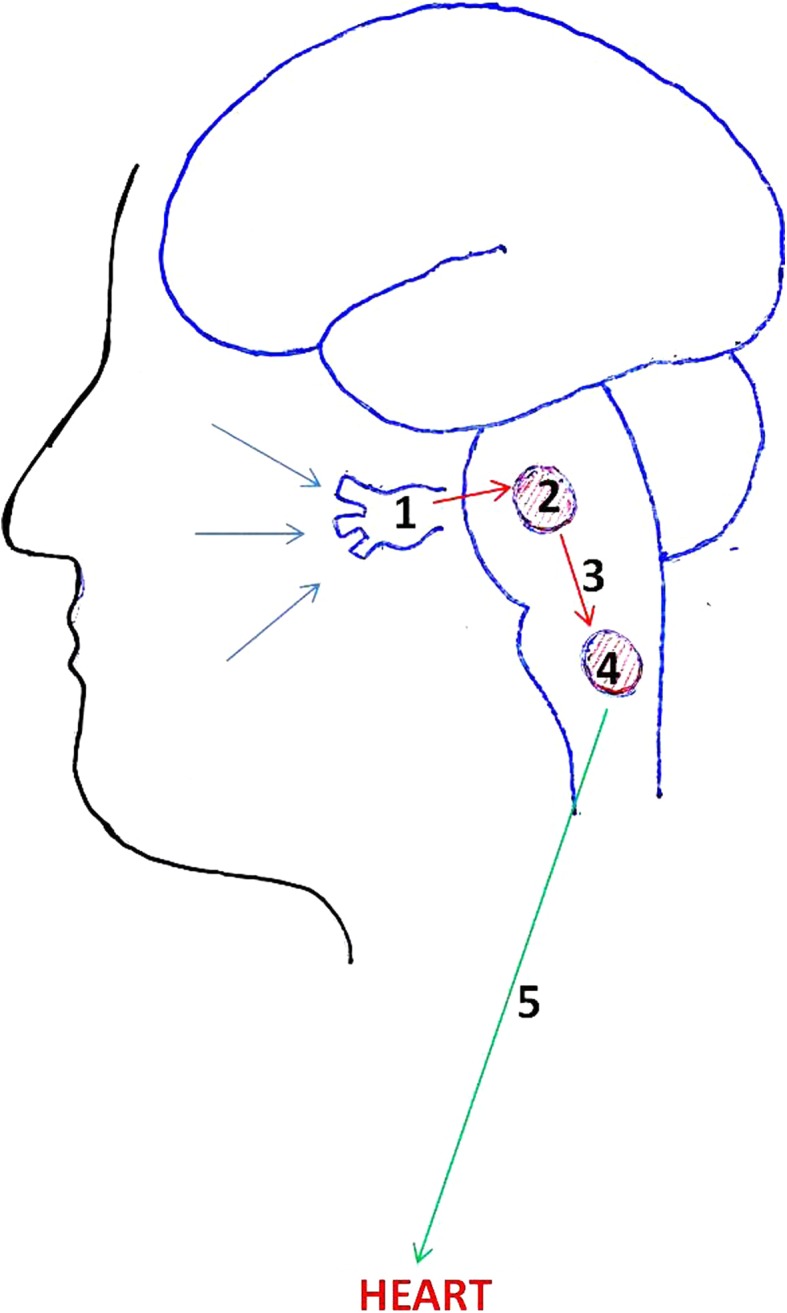

The afferent arm of the trigeminocardiac reflex arc is formed by the sensory nerve endings of the fifth cranial nerve which sends neuronal signals via the Gasserian ganglion to the trigeminal sensory nucleus. Further from the sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve afferent reflex arm is connected to the efferent pathway via the short internuncial fibres in the reticular formation, connecting the motor nucleus of the vagus nerve. Cardioinhibitory efferent fibres arise from the motor nucleus of the vagus nerve and end in the myocardium imposing the vagus mediated negative chronotropic and inotropic responses on the heart (Figs. 1 and 2) [8, 9].

Fig. 1.

Trigeminocardiac reflex arc

Fig. 2.

Pathway of trigemino-vagal innervations to the heart. (1 Gasserian ganglion. 2 Sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve. 3 Short internuncial fibers. 4 Motor nucleus of the vagus nerve. 5 Vagus Nerve)

Predisposing and Risk Factors

Lübbers et al. [10] have classified the various craniomaxillofacial surgical procedures into low (temporomandibular joint surgery, Le Fort I osteotomy, elevation of zygomatic fractures), medium (skull base surgery) and high risk procedures (ophthalmic surgery, strabismus surgery, orbital extenteration, fractures in children with cardiac disease) for precipitation of the trigeminocardiac reflex. Campbell, Rodrigo and Cheung have highlighted the various potential predisposing factors for trigeminocardiac reflex, summarized in Table 2 [11]. Apart from maxillofacial surgery, clinicians involved in dealing with the patients requiring ophthalmic and neurosurgical intervention should also be familiar with the occurrence of this reflex.

Table 2.

Predisposing and risk factors for trigeminocardiac response

| 1 | Children |

| 2 | Males |

| 3 | High sympathetic activity |

| 4 | Hypoxemia |

| 5 | Hypercarbia |

| 6 | Light anesthesia |

| 7 | Neuromuscular blocking agents |

| 8 | Opioids |

| 9 | β-Adrenergic blockers |

| 10 | Strength and duration of stimulus |

Maxillofacial Surgery and Trigeminocardiac Reflex

Precious and Skulsky [12] have reported the incidence of reflex bradycardia during maxillofacial surgical procedures to be as high as 1.6 %. The highest incidence of 32–90 % has been reported in strabismus surgery followed by blepharoplasty (25 %) [10]. Bainton and Lizi [13] reported a case of cardiac asystole in a patient undergoing surgery for zygomatic arch fracture. Loewinger et al. [14] also reported a case of bradycardia during elevation of a zygomatic arch fracture in the same year. Eversince there have been numerous reports of reflex bradycardia or asystole confirming the involvement of all the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve in the occurrence of the trigeminocardiac reflex [15]. Various reports and reviews on trigeminocardiac reflex during maxillofacial surgery or facial trauma have been summarized in Table 1.

Prevention and Management

Arasho et al. [1] have summarized the management of the trigeminocardiac reflex into the following points : (1) Identification of the risk factors and their modification; (2) Prophylactic treatment using vagolytic drugs and/or peripheral nerve blocks in procedures involving manipulations of the trigeminal nerve; (3) Cardiovascular monitoring during anaesthesia particularly in cases with risk of reflex precipitation; (4) In case of an event, cessation of the manipulation of the nerve with consideration of administration of vagolytic agents or adrenaline in cases on asystole. Prophylactic preoperative administration of intramuscular atropine or glycopyrollate is debatable since it has been found to be ineffective in some cases, but is administered by most anaesthetists in practice [16]. The depth of anaesthesia should be adequate, as the deeper planes have been observed to obviate the cardio vascular depressive responses to stimulation of the trigeminal nerve.

Controlled ventilation is the norm, along with monitoring of arterial oxygen saturation and end tidal carbon dioxide to prevent both hypoxemia and hypercarbia, which are adjuvant contributing factors to triggering the reflex. Continuous intraoperative cardiovascular monitoring should be practiced, which provides a safety feature, ensuring prompt detection of any adverse event and rapid management. Abrupt and sustained manipulation of the trigeminal nerve should be avoided. Clinical studies point out that the nature of the stimulus is the most important risk factor in inducing this reflex—abrupt and sustained traction is more reflexogenic than smooth and gentle traction [17].

Communication between operating surgeon and anaesthetist, specially during sensitive portions like elevation of the zygoma or manipulation of the orbit/orbital muscles, should be maintained. Use of potentially bradycardic and hypotensive drugs like potent narcotics, B-blockers, and calcium channel blockers should be avoided, as is the use of inhalational anesthetics like halothane [18–20].

In the event of bradycardia occurring, surgical manipulation should immediately be stopped. Though most authors concede to the fact that trigeminal cardiac response is a transient response to manipulation of the trigeminal nerve, which recovers on cessation of the stimulus [8, 21], there are numerous reports of severe bradycardia and asystole, where the additional administration of anticholinergic agents is warranted. The use of intravenous atropine/glycopyrollate has been advocated. Local infiltration or peripheral nerve block may be tried, especially if controlled arterial hypotension is to be practiced, as is usual in these cases [22]. It has been reported that nerve block taken in conjunction with anticholinergics, completely abolished the occurrence of the occulocardiac reflex in extraoccular muscle surgery [23]. In cases refractory to vagolytic agents epinephrine has been advocated [24]. Sudden asystole without preceding bradycardia has also been reported which has responded to simple cessation of insult [25].

Conclusion

For the effective management of this complication it is necessary that the concerned anaesthesiologist and the maxillofacial surgeon be aware of the potential for its occurrence in maxillofacial surgeries due to the stimulation of the branches of trigeminal nerve [26] as well as the provoking factors which include patient physiology, anaesthetic technique and the surgical procedure.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Contributor Information

Darpan Bhargava, emaildarpan@gmail.com.

Shaji Thomas, Email: shajihoss@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Arasho B, Sandu N, Spiriev T, Prabhakar H, Schaller B. Management of the trigeminocardiac reflex: facts and own experience. Neurol India. 2009;57(4):375–380. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.55577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer DF, Youkilis A, Schenck C, Turner CR, Thompson BG. The falcine trigeminocardiac reflex: case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2005;63(2):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumada M, Dampney RA, Reis DJ. The trigeminal depressor response: a novel vasodepressor response originating from the trigeminal system. Brain Res. 1977;119:305–326. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moonie GT, Ress EL, Elton D. The oculocardiac reflex during strabismus surgery. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1964;11:621. doi: 10.1007/BF03004107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts RS, Best JA, Shapiro RD. Trigeminocardiac reflex during temporomandibular joint arthroscopy: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57(7):854–856. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90829-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prabhu VC, Bamber NI, Shea JF, Jellish WS. Avoidance and management of trigeminocardiac reflex complicating awake-craniotomy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110(10):1064–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelly MP, Church JJ. Bradycardia and facial surgery [letter] Anaesthesia. 1988;43:422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1988.tb09042.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang S, Lanigan DT, van der Wal M. Trigeminocardiac reflexes: maxillary and mandibular variants of the oculocardiac reflex. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38:757–760. doi: 10.1007/BF03008454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cha ST, Eby JB, Katzen JT, Shahinian HK. Trigeminocardiac reflex: a unique case of recurrent asystole during bilateral trigeminal sensory root rhizotomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002;30(2):108–111. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2001.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lübbers HT, Zweifel D, Grätz KW, Kruse A. Classification of potential risk factors for trigeminocardiac reflex in craniomaxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(6):1317–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell R, Rodrigo D, Cheung L. Asystole and bradycardia during maxillofacial surgery. Anesth Prog. 1994;41(1):13–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Precious DS, Skulsky FG. Cardiac dysrhythmias complicating maxillofacial surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;19:279. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bainton R, Lizi E. Cardiac asystole complicating zygomatic arch fracture. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64:24–25. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loewinger J, Cohen M, Levi E. Bradycardia during elevation of a zygomatic arch fracture. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45:710–711. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(87)90315-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohluli B, Ashtiani AK, Khayampoor A, Sadr-Eshkevari P. Trigeminocardiac reflex: a MaxFax literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(2):184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prabhakar H, Rath GP, Arora R. Sudden cardiac standstill during skin flap elevation in a patient undergoing craniotomy. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2007;19:203–204. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31804e45e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanc VF, Hardy JF, Milot J, Jacob JL. The oculocardiac reflex: a graphic and statistical analysis in infants and children. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1983;30:360–369. doi: 10.1007/BF03007858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivard JC, Lebowitz PW. Bradycardia after alfentanil-succinylcholine. Anesth Analg. 1988;67(9):907. doi: 10.1213/00000539-198809000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starr NJ, Sethna DH, Estafanous FG. Bradycardia and asystole following the rapid administration of sufentanil with vecuronium. Anesthesiology. 1986;64(4):521–523. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198604000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmeling WT, Kampine JP, Warltier DC. Negative chronotropic actions of sufentanil and vecuronium in chronically instrumented dogs pretreated with propranolol and/or diltiazem. Anesth Analg. 1989;69(1):4–14. doi: 10.1213/00000539-198907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shearer ES, Wenstone R. Bradycardia during elevation of zygomatic fractures. A variation of the occulocardiac reflex. Anaesthesia. 1987;42:1207–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1987.tb05231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanc VF. Trigeminocardiac reflexes. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38(6):696–699. doi: 10.1007/BF03008444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misurya VK, Singh SP, Kulshrestha VK. Prevention of oculocardiac reflex (O.C.R) during extraocular muscle surgery. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1990;38:85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prabhakar H, Ali Z, Rath GP. Trigemino-cardiac reflex may be refractory to conventional management in adults. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2008;150:509–510. doi: 10.1007/s00701-008-1516-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prabhakar H, Anand N, Chouhan RS, Bithal PK. Brief report of special case: sudden asystole during surgery in the cerebellopontine angle. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:699–700. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0712-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morey TE, Bjoraker DG. Asystole during temporomandibular joint arthrotomy. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:1488–1491. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199612000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch MJ, Parker H. Forensic aspects of ocular injury. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2000;21(2):124–126. doi: 10.1097/00000433-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yilmaz T, Erol FS, Yakar H, Köhle U, Akbulut M, Faik Ozveren M. Delayed trigeminocardiac reflex induced by an intraorbital foreign body. Case report. Ophthalmologica. 2006;220(1):65–68. doi: 10.1159/000089277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaller BJ, Buchfelder M. Delayed trigeminocardiac reflex induced by an intraorbital foreign body. Ophthalmologica. 2006;220(5):348. doi: 10.1159/000094629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webb MD, Unkel JH. Anesthetic management of the trigeminocardiac reflex during mesiodens removal—a case report. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):7–8. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2007)54[7:AMOTTR]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arakeri G, Arali V. A new hypothesis of cause of syncope: trigeminocardiac reflex during extraction of teeth. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74(2):248–251. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohluli B, Bayat M, Sarkarat F, Moradi B, Tabrizi MH, Sadr-Eshkevari P. Trigeminocardiac reflex during Le Fort I osteotomy: a case-crossover study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110(2):178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arakeri G, Brennan PA. Trigeminocardiac reflex: potential risk factor for syncope in exodontia? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(11):2921. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnan B. Re: classification of potential risk factors for trigeminocardiac reflex in craniomaxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(4):960. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bohluli B, Schaller BJ, Khorshidi-Khiavi R, Dalband M, Sadr-Eshkevari P, Maurer P. Trigeminocardiac reflex, bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy, Gow-Gates block: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(9):2316–2320. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puri AS, Thiex R, Zarzour H, Rahbar R, Orbach DB. Trigeminocardiac reflex in a child during pre-Onyx DMSO injection for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma embolization. A case report. Interv Neuroradiol. 2011;17(1):13–16. doi: 10.1177/159101991101700103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potti TA, Gemmete JJ, Pandey AS, Chaudhary N. Trigeminocardiac reflex during the percutaneous injection of ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx) into a juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a report of two cases. J Neurointerv Surg. 2011;3(3):263–265. doi: 10.1136/jnis.2010.003723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yorgancilar E, Gun R, Yildirim M, Bakir S, Akkus Z, Topcu I. Determination of trigeminocardiac reflex during rhinoplasty. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41(3):389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wartak SA, Mehendale RA, Lotfi A. A unique case of asystole secondary to facial injury. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:382605. doi: 10.1155/2012/382605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schames SE, Schames J, Schames M, Chagall-Gungur SS. Sleep bruxism, an autonomic self-regulating response by triggering the trigeminal cardiac reflex. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2012;40(8):670-1–674-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]