ABSTRACT

Infection with Streptococcus pyogenes is associated with a breadth of clinical manifestations ranging from mild pharyngitis to severe necrotizing fasciitis. Elevated levels of intracellular copper are highly toxic to this bacterium, and thus, the microbe must tightly regulate the level of this metal ion by one or more mechanisms, which have, to date, not been clearly defined. In this study, we have identified two virulence mechanisms by which S. pyogenes protects itself against copper toxicity. We defined a set of putative genes, copY (for a regulator), copA (for a P1-type ATPase), and copZ (for a copper chaperone), whose expression is regulated by copper. Our results indicate that these genes are highly conserved among a range of clinical S. pyogenes isolates. The copY, copA, and copZ genes are induced by copper and are transcribed as a single unit. Heterologous expression assays revealed that S. pyogenes CopA can confer copper tolerance in a copper-sensitive Escherichia coli mutant by preventing the accumulation of toxic levels of copper, a finding that is consistent with a role for CopA in copper export. Evaluation of the effect of copper stress on S. pyogenes in a planktonic or biofilm state revealed that biofilms may aid in protection during initial exposure to copper. However, copper stress appears to prevent the shift from the planktonic to the biofilm state. Therefore, our results indicate that S. pyogenes may use several virulence mechanisms, including altered gene expression and a transition to and from planktonic and biofilm states, to promote survival during copper stress.

IMPORTANCE Bacterial pathogens encounter multiple stressors at the host-pathogen interface. This study evaluates a virulence mechanism(s) utilized by S. pyogenes to combat copper at sites of infection. A better understanding of pathogen tolerance to stressors such as copper is necessary to determine how host-pathogen interactions impact bacterial survival during infections. These insights may lead to the identification of novel therapeutic targets that can be used to address antibiotic resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as group A Streptococcus (GAS), is a Gram-positive obligate human pathogen and the causative agent of a wide variety of diseases ranging from relatively mild clinical illnesses such as pharyngitis, cellulitis, and impetigo to life-threatening puerperal sepsis, myositis, toxic shock syndrome, and necrotizing fasciitis (1, 2). In some instances, S. pyogenes infections can lead to postinfectious sequelae, such as acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (1–3).

Several factors, including micronutrients such as trace elements, metal ions, and vitamins as well as cytokines produced by inflammatory cells, are thought to play a role in the progression and severity of S. pyogenes disease (4). Homeostatic systems involved in regulating intracellular levels of iron, manganese, zinc, cobalt, and heme play a critical role in S. pyogenes survival, as demonstrated in a wide variety of animal models (5–7). However, the mechanism(s) that prevents copper toxicity in S. pyogenes has not been previously described. In view of the ability of copper to promote the generation of toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) (8–10), bacteria have evolved mechanisms to tightly regulate copper levels (11, 12). Copper-regulating systems have been identified in Gram-positive organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (13), Streptococcus mutans (14), Lactococcus lactis (15), and Enterococcus hirae (16). In each of these organisms, the cop operon encodes a copper-transporting CPx-type ATPase (CopA/CopB), a copper-responsive repressor that represses the operon under conditions of low copper concentrations (CopY/CopR), and a copper chaperone that shuttles copper intracellularly (CopZ) (8, 13–17). Animal studies have demonstrated that deletion of a copper-transporting ATPase results in decreased survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (18), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19), Listeria monocytogenes (20), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (21), and S. pneumoniae (13, 22).

In view of the importance of protective mechanisms against copper in a broad range of pathogenic bacterial species, we hypothesized that S. pyogenes utilizes a similar mechanism(s) to enhance its survival in an infected host. S. pyogenes infection results in a severe inflammatory response that involves the production of a number of effectors, including ROS, cytokines, and a spectrum of acute-phase reactants (23). Strikingly, S. pyogenes lacks common oxidative stress resistance factors such as catalase (24). Therefore, tight regulation of copper, a promoter of ROS generation, is likely to be of extreme importance at sites of infection (11, 12, 25, 26). Therefore, we set out to define the mechanism(s) by which S. pyogenes controls intracellular copper levels and, thus, copper toxicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

This study utilized S. pyogenes MGAS5005, a clinical M1T1 strain isolated from a case of invasive S. pyogenes disease (27, 28). Planktonic and biofilm cultures were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (Becton-Dickinson) supplemented with 2% yeast extract (THY) (Fisher Scientific). Before the addition of CuSO4 (Sigma-Aldrich), bacteria were centrifuged at 4,400 × g for 15 min, and the bacterial pellets were washed twice and suspended in chemically defined medium (CDM) (29). Cultures were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2, serially diluted, and plated onto THY agar. Heterologous expression assays were performed by using Escherichia coli W3110, a K-12 wild-type strain (30), and a mutant strain, W3110ΔcopA (31). E. coli strains were grown (with shaking) in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Amresco) at 37°C before and after the addition of CuSO4. Following incubation with copper, the cultures were serially diluted and plated onto LB agar.

Planktonic assays.

S. pyogenes cultures were grown to logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of ∼0.5), centrifuged, suspended in CDM (29), and diluted to 103 CFU/ml prior to the addition of CuSO4. Triplicate cultures were then incubated for 24 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. At 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h, aliquots were removed, serially diluted, plated onto THY agar, and then incubated in 37°C overnight prior to colony counts.

Biofilm assays.

For biofilm growth, S. pyogenes cultures were grown to logarithmic phase (OD600 of ∼0.5), centrifuged, suspended in CDM (29), and diluted prior to aliquoting into 24-well tissue culture-treated polystyrene plates (Corning Costar) for biofilm growth. Cultures were incubated with 0, 50, 75, or 100 μM CuSO4 for 24 h at 37°C. For experiments with established biofilms, S. pyogenes cultures were incubated for 24 h prior to the exchange of medium with copper-containing medium and then incubated for an additional 24 h. Biofilms were serially diluted and plated onto THY agar for viable counts. Biofilm formation was assessed by using a crystal violet assay, as previously described (32).

ICP-OES analysis.

All samples were analyzed by using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Teledyne Leeman Labs). The wavelengths for the detection of each metal were as follows: 324.754 and 327.396 nm for Cu and 257.610 and 259.372 nm for Mn. Samples were centrifuged and washed with 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 0.5 mM EDTA, followed by two washes with 10 ml of PBS. After a final wash, bacteria were suspended in 2 ml PBS prior to the addition of 10 mg/ml lysozyme. After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, 1 ml of 6% HNO3 plus 0.1% Triton X-100 was added, and samples were incubated at 95°C for 30 min. Following centrifugation for 10 min at 15,700 × g, supernatants were removed, added to tubes containing 3.2 ml 1% HNO3, and stored at 4°C until ICP-OES analysis was performed. Intracellular copper levels were calculated by using metal standard solutions and normalized to optical densities.

Sequence alignment.

For sequence identity analysis, we utilized the following S. pyogenes strains of multiple M serotypes: MGAS5005 (M1) (GenBank accession number CP000017.2), MGAS315 (M3) (accession number AE014074.1), MGAS10750 (M4) (accession number CP000262), Manfredo (M5) (accession number NC_009332.1), MGAS2096 (M12) (accession number NC_008023), MGAS8232 (M18) (accession number AE009949), and MGAS6180 (M28) (accession number CP000056). Additional streptococcal strains included S. mutans JH1005 (GenBank accession number AF296446.1), S. pneumoniae D39 (accession number CP000410.1), and E. hirae ATCC 9790 (accession number CP003504.1). ClustalW2 analysis was used to perform a multiple DNA sequence alignment of a 200-bp region upstream of the annotated copY genes of each strain (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/). ClustalW2 and BLAST were performed to align and assess the similarity of features as well as to determine the percent identity of CopA sequences of E. coli W3110 (GenBank accession number WP_000083955.1) and S. pyogenes MGAS5005 (accession number AAZ52023.1). All sequences are available in the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/index.htm).

RNA isolation.

Bacteria exposed to CuSO4 were pelleted by centrifugation at 15,700 × g for 10 min at 4°C. To isolate RNA, culture pellets were suspended in 1 ml of RNA Pro solution (MP Biomedicals), transferred to a Lysing Matrix B FastPrep-24 tube (MP Biomedicals), and then processed with a FastPrep EP120 instrument for 40 s at a setting of 6.0. Samples were centrifuged at 15,700 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Approximately 750 μl of the supernatant was transferred to a sterile 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and incubated for 5 min at room temperature, after which 300 μl of chloroform was added. The samples were incubated for 5 min at room temperature, transferred to a phase lock tube (2 ml, heavy gel; 5 Prime), and then centrifuged at 15,700 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The top layer was transferred to a second phase lock tube (2 ml, heavy gel; 5 Prime), and 300 μl of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) was added prior to centrifugation at 15,700 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The aqueous layer was transferred to an RNase-free 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube, 500 μl of ice-cold 100% ethanol was added, and samples were incubated for a minimum of 30 min at −20°C. RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 15,700 × g for 30 min at 4°C and washed with 500 μl of ice-cold 75% ethanol, followed by air drying. RNA was suspended in 100 μl of nuclease-free water and measured on a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. Samples were treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) for 45 min at room temperature. A Qiagen RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (Qiagen) was used to clean up RNA, according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was stored at −80°C until it was reverse transcribed into cDNA by using the Superscript III first-strand synthesis system for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

RT-PCR.

Cultures in CDM were incubated with 25 μM CuSO4 at 37°C for 45 min. RNA and cDNA were prepared as described above. Primers for the intergenic regions between copY and copA (primers RT copY FWD and RT copA REV) and between copA and copZ (primers RT copA FWD and RT copZ REV) (Table 1) were used for PCR.

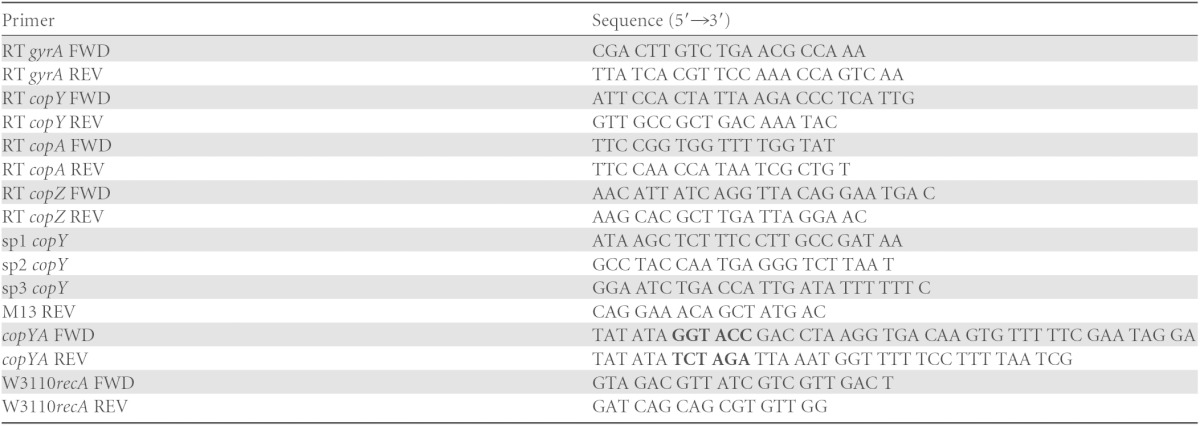

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this studya

Restriction sites are in boldface type.

Real-time quantitative PCR.

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed on a 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using SYBR Select master mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative PCRs were run by using standard curve setting and ramp speed, according to the manufacturer's protocol. The critical threshold cycle (CT) is defined as the cycle at which fluorescence becomes detectable above the background and is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the initial concentration of the template. A standard curve was plotted for each reaction with CT values obtained from the amplification of known quantities of genomic MGAS5005 DNA. The standard curves were used to transform CT values of the experimental samples into the relative number of DNA molecules. The quantity of cDNA for each experimental gene was normalized to the quantity of the constitutively transcribed control gene (gyrA) in each sample. The fold change in transcript levels was calculated by determining the ratio of the levels of copY and copA cDNAs from MGAS5005 incubated with CuSO4 to the levels of copY and copA cDNAs from unexposed samples.

5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends.

Cultures in CDM were incubated with 25 μM CuSO4 at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 45 min. RNA was isolated from these cultures as described above. A second-generation 5′/3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) kit (Roche) was used with primers sp1, sp2, and sp3 (Table 1), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Extension products were run on 2% agarose gels, ligated into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and then transformed into DH5α chemically competent cells by using standard molecular cloning techniques (33). Extension products were sequenced (Genewiz) from the vector by using the standard M13 REV primer (Table 1) to map the transcriptional start site.

Cloning of the cop operon of S. pyogenes.

The copYA primers (Table 1) were used to amplify the promoter of copY, as well as the complete copY and copA genes from MGAS5005, by using 5 Prime HotMasterMix. The PCR product was purified by using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). The purified product as well as pSU18 (15) were double digested with KpnI (NEB) and XbaI (NEB) and then ligated together, resulting in pSU18::copYcopA. Standard molecular cloning techniques were performed for making chemically competent E. coli W3110ΔcopA cells and for transformations (33). The plasmid was constructed by using SnapGene 2.6.1.

Complementation assays.

Cultures of E. coli W3110, E. coli W3110ΔcopA, E. coli W3110ΔcopA with pSU18::copYcopA, and E. coli W3110ΔcopA with pSU18 (vector control) grown overnight were diluted 1:100 in LB broth (Amresco) and grown (with shaking) for 1 h at 37°C. After 1 h, cultures were either streaked onto plates containing copper or exposed to copper in liquid culture for 8 h. For plates, 10 μl of each subculture was streaked as a lawn onto LB agar containing 0, 1, 2, or 3 mM CuSO4 and grown overnight at 37°C. For liquid cultures, cultures were incubated with 0.5, 1, 1.5, or 2 mM CuSO4 with shaking at 37°C for 8 h. After 8 h, the optical density (OD600) was measured by using a BioPhotometer instrument (Eppendorf). For verification of the expression of the MGAS5005 cop operon in E. coli W3110ΔcopA containing pSU18::copYcopA, RNA was isolated from E. coli W3110ΔcopA, E. coli W3110ΔcopA with pSU18::copYcopA, and E. coli W3110ΔcopA with pSU18 (vector control) after 8 h in the presence of 1 mM CuSO4. RNA and cDNA were prepared as described above, and the MGAS5005 copA primers and the E. coli W3110 recA primers (Table 1) were used for PCR.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed by using GraphPad Prism, version 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Experiments were repeated three times in triplicate, and significance was determined by using an unpaired t test. All P values were two tailed at a 95% confidence interval, and values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

S. pyogenes clinical isolates contain a cop operon-like locus.

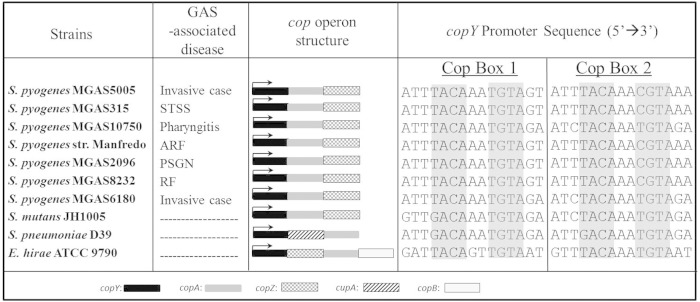

Genes involved in copper homeostasis are best characterized in E. hirae (16, 34–39) but have also been studied in other streptococcal organisms, including S. mutans (14, 36) and S. pneumoniae (13, 40). In these organisms as well as in other pathogenic bacteria, the genes are located within a cop operon and represent an important virulence mechanism (13, 18–21). Therefore, the presence of a cop operon-like locus would be consistent with a potential role of this locus in S. pyogenes pathogenesis. To determine whether cop operon-like regions are conserved among S. pyogenes strains, we analyzed the genomes of clinical isolates from patients with noninvasive and invasive diseases. Each S. pyogenes strain contained a putative Cu-responsive transcriptional repressor, copY; a heavy metal CPx-type ATPase, copA; and a copper chaperone protein, copZ (17, 41) (Fig. 1). Compared to E. hirae, S. pyogenes CopY exhibited 34% identity, CopA exhibited 44% identity, and CopZ exhibited 35% identity. However, unlike E. hirae, none of the S. pyogenes strains contained CopB, an additional CPx-type ATPase. In E. hirae, CopB acts as a copper exporter, and although initial evidence was consistent with a role for CopA in copper import (42), recent reports support the notion that this subgroup of P-type ATPases acts in copper efflux (16, 43, 44). S. pyogenes proteins shared the highest percent sequence similarity to S. mutans, with 51% identity to CopY, 59% to CopA, and 46% to CopZ. S. pyogenes also shared sequence identity with S. pneumoniae cop operon-encoded proteins (38% identity to CopY and 44% to CopA) but lacked CupA. CupA, which plays a role in copper resistance in S. pneumoniae (13, 22), has 33% identity to a hypothetical protein, Spy_0115, of unknown function in S. pyogenes MGAS5005.

FIG 1.

S. pyogenes clinical isolates contain a cop operon-like locus. Shown are annotated cop operons of S. pyogenes clinical isolates, S. mutans, S. pneumoniae, and E. hirae. For each strain, the sequences upstream of the copY translational start site were aligned for conserved cop boxes (shaded gray), which represent putative CopY binding sites. STSS, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome; ARF, acute rheumatic fever; PSGN, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis; RF, rheumatic fever. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: CP000017.2 for S. pyogenes MGAS5005 (M1), AE014074.1 for S. pyogenes MGAS315 (M3), CP000262 for S. pyogenes MGAS10750 (M4), NC_009332.1 for S. pyogenes strain Manfredo (M5), NC_008023 for S. pyogenes MGAS2096 (M12), AE009949 for S. pyogenes MGAS8232 (M18), CP000056 for S. pyogenes MGAS6180 (M28), AF296446.1 for S. mutans JH1005, CP000410.1 for S. pneumoniae D39, and CP003504.1 for E. hirae ATCC 9790.

Next, we examined the region upstream of the copY open reading frame (ORF) for conserved cop boxes. In order to repress cop operon expression, CopY binds two cop boxes upstream of the copY translational start site at the sequence T/GACANNT/CGTA (15, 16, 39, 41). cop box 1 represents the conserved CopY binding site furthest upstream from the copY translational start site, and cop box 2 represents the closest binding site to the copY ORF. Alignment revealed two cop boxes in the upstream region of the copY ORF in each of the clinical strains. Our results indicate that the gene orientation and copY promoters of S. pyogenes cop operon-like loci were highly conserved among a range of clinical isolates.

Characterization of the S. pyogenes cop operon.

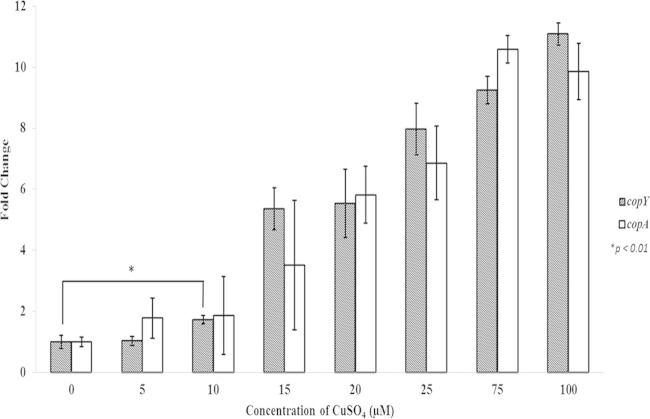

Given that the S. pyogenes cop operon locus has homology to established cop operons of other species and that these operons play a role in tightly regulating intracellular copper levels, we assessed whether expression of this locus was responsive to copper. S. pyogenes cultures were incubated with a range of copper concentrations (5, 10, 15, 25, 75, and 100 μM) for 45 min, followed by real-time quantitative PCR to quantitate the levels of copY and copA mRNA expression. Gene expression was induced in a copper concentration-dependent manner, with copper concentrations as low as 10 μM resulting in a statistically significant 2-fold increase of copY and copA gene expression levels (Fig. 2). In the presence of 75 to 100 μM copper, the enhancement of specific gene expression appeared to plateau at ∼10-fold.

FIG 2.

Real-time quantitative PCR measurement of copYA mRNA expression in response to copper. Cultures of S. pyogenes grown in CDM to logarithmic phase were incubated with the indicated concentrations of CuSO4 for 45 min. RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed to make cDNA, and cop operon mRNA levels were determined by real-time quantitative PCR with copY and copA primers directed against their respective genes. These data are representative of the fold increases in gene expression levels ± standard deviations from three independent experiments (P values were determined by an unpaired t test).

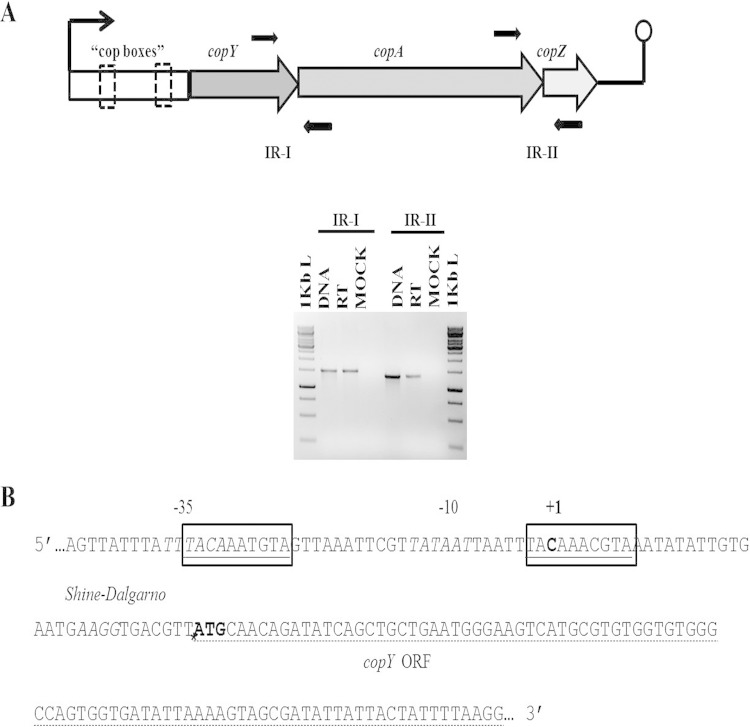

Established cop operons in other species are transcribed in a polycistronic manner. In view of this observation, we determined whether the transcription of the S. pyogenes copYAZ genes was also polycistronic and, if so, the location of the transcriptional start site. To assess the polycistronic nature of the copY, copA, and copZ genes, we exposed S. pyogenes to 25 μM copper for 45 min and isolated RNA. We reverse transcribed RNA to cDNA and amplified the intergenic regions between copY and copA as well as those between copA and copZ. PCR products run on an agarose gel confirmed the expression of the intergenic regions, indicating that these genes are polycistronic (Fig. 3A). Next, we exposed S. pyogenes to 25 μM copper and prepared RNA for 5′ RACE to amplify the copY promoter and map the transcriptional start site. Our results indicated that a transcriptional start site is located at a cytosine 34 nucleotides upstream of the copY translational start site. The start site was located within the inverted repeats of one of the cop boxes (Fig. 3B). Our results demonstrate the polycistronic nature of the S. pyogenes copYAZ genes, map the location of the transcriptional start site within a conserved cop box, and raise the possibility that the S. pyogenes cop operon, as with other cop operon-containing pathogens, plays a role in S. pyogenes susceptibility to copper.

FIG 3.

Organization of the S. pyogenes cop operon promoter. (A) Cultures of S. pyogenes in CDM were induced in logarithmic phase with 25 μM CuSO4 for 45 min. RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed to make cDNA. As indicated, primers (black arrows) in the intergenic regions (intergenic region I [IR-I] and IR-II) of the cop operon genes were amplified by using PCR. The PCR products of IR-I and IR-II are 1,535 bp and 1,357 bp, respectively. (B) The transcriptional start site of the S. pyogenes cop operon was mapped by 5′ RACE. Features (5′→3′) are indicated as follows: conserved cop boxes are outlined and underlined, −35 and −10 regions are in italic type, the transcriptional start site is in boldface type and indicated by a +1, a potential Shine-Dalgarno sequence is in italic type, the translational start site of the copY open reading frame is indicated by an asterisk and ATG in boldface type, and the copY ORF is underlined with a dashed line. Sequenced 5′ RACE products consisted of 5/5 products (400 bp) that matched at C (position −34), 2/2 (420 bp) that matched at A (position −35), and 0/2 (300 bp) that did not match. It was hypothesized that the potential start site is the C residue located at position −34 from the copY ORF, because 400 bp accounted for 70% of the PCR product sizes.

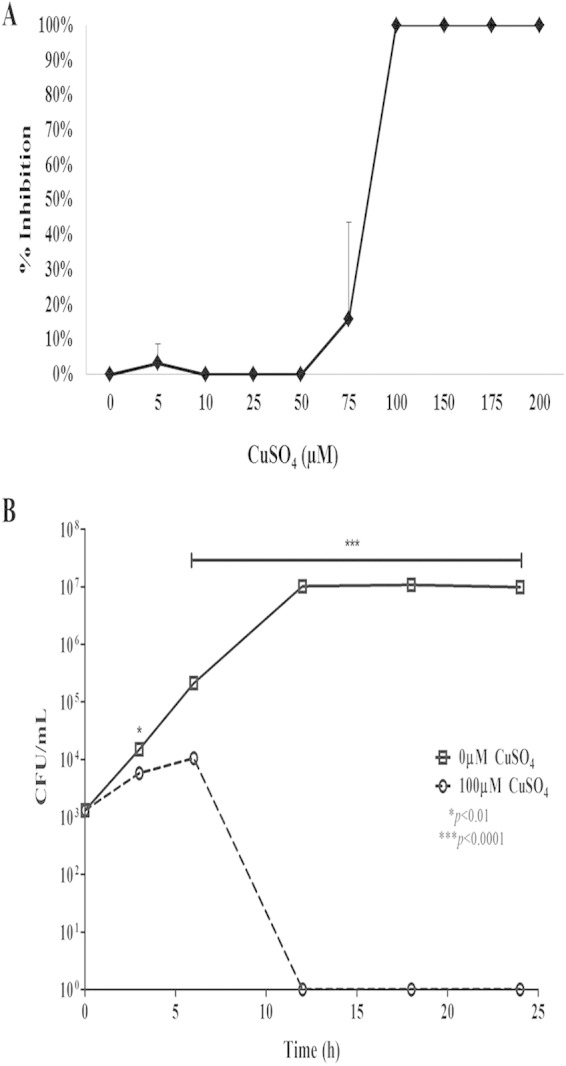

Copper is toxic to S. pyogenes growth.

Considering that S. pyogenes is likely to encounter copper in vivo (25), we determined whether copper was toxic for S. pyogenes and, if so, at what concentration. S. pyogenes cultures were incubated with increasing concentrations of copper for 24 h, after which viable cell counts were obtained. We observed that a concentration of 75 μM had considerable variability in the toxic effect on S. pyogenes, as seen by the large standard deviation associated with 20% growth inhibition (Fig. 4A). Concentrations of >75 μM were toxic to S. pyogenes, with complete killing of bacteria after 6 h of incubation with 100 μM copper (Fig. 4B). Thus, it is quite likely that 75 μM copper represents the tipping point for toxicity. As shown in Fig. 2, we observed a plateau in the expression levels of copY and copA in cultures incubated with either 75 μM or 100 μM copper. Based on these results, we suggest that maximal cop operon expression is insufficient to limit toxicity at concentrations of copper of >75 μM.

FIG 4.

Growth of S. pyogenes in the presence of copper. (A) S. pyogenes cultures were incubated with increasing concentrations of copper for 24 h. Bacteria were serially diluted and plated for viable counts. Results are graphed as copper concentration versus percent inhibition of growth compared to the unexposed samples. (B) S. pyogenes cultures were incubated with 0 or 100 μM copper for 24 h. At 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h, cultures were serially diluted and plated onto THY agar, and viable bacteria were counted. Data represent means ± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments (P values were determined by an unpaired t test).

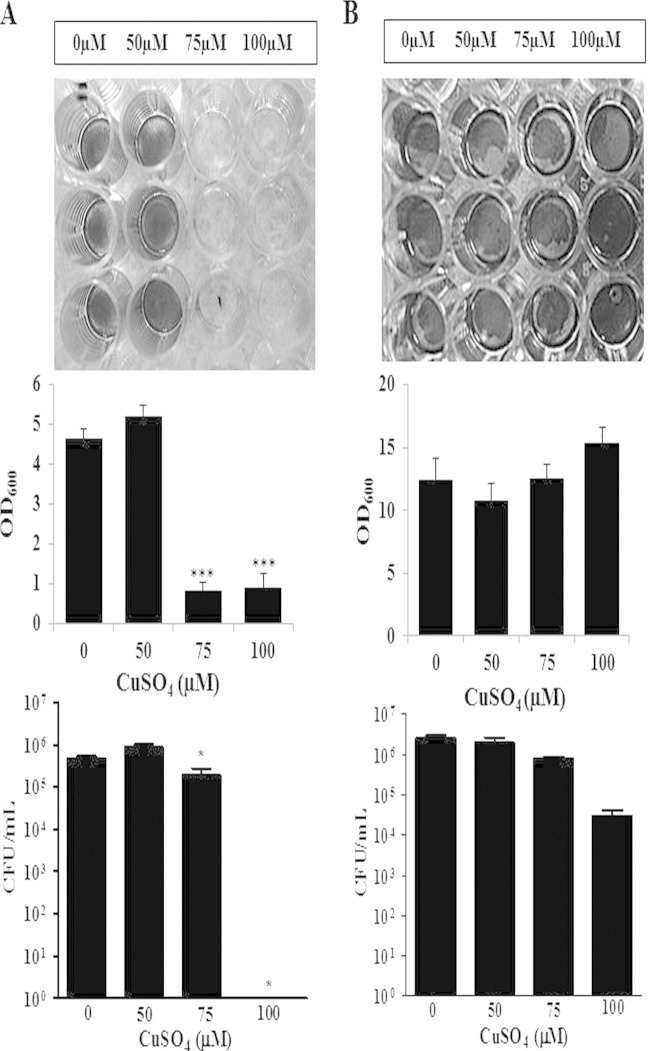

The ability of GAS to form complex bacterial biofilm communities is thought to be an important mechanism for its survival and persistence in human carriage and invasive infections (45–47). Given the central role of biofilms in S. pyogenes pathogenesis, it was important to determine if copper had the same effects on S. pyogenes in a biofilm state as with planktonic bacteria. S. pyogenes cultures were incubated with increasing copper concentrations (0 to 100 μM) for 24 h, after which the bacteria were assessed for viability and biofilm formation. As shown in Fig. 5A, biofilm formation was inhibited in the presence of copper at 75 μM but not at lower concentrations. However, a decrease in cell viability was not associated with the lack of biofilm formation. Thus, the ability to form a biofilm appears to be more sensitive to copper than do growth and survival of planktonic bacteria in the presence of copper (Fig. 4).

FIG 5.

Copper inhibits biofilm formation. For biofilm experiments, S. pyogenes was seeded into wells in which copper was added initially (A) or copper was added into wells with biofilms that were established after a 24-h incubation (B). Serial dilutions and plating techniques were used to count viable bacteria. Biofilm formation was assessed by crystal violet staining and optical density measurements. Photographs of crystal violet-stained biofilms were taken for visualization. Assays were performed in triplicate, and means ± standard errors of the means were graphed and used for statistical analysis. These data are representative of data from three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001 [determined by an unpaired t test]).

We next investigated the potential effect of copper on established biofilms. S. pyogenes cells were cultured in wells for 24 h, after which increasing copper concentrations were added (0 to 100 μM), and incubation was continued for an additional 24 h. Viability and biofilm formation were then assessed. As shown in Fig. 5B, bacterial viability and biofilm stability were unaffected by concentrations of copper of up to 100 μM. These results are in striking contrast to the toxic effect of high concentrations of copper on the growth and survival of planktonic S. pyogenes (Fig. 4).

The S. pyogenes cop operon plays a role in copper resistance.

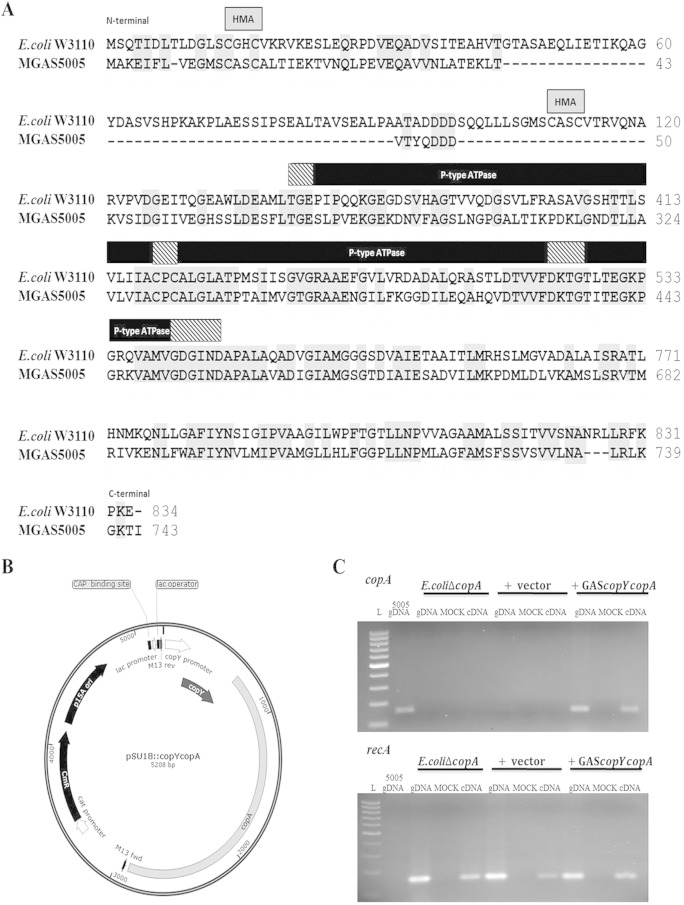

To formally prove that the S. pyogenes cop operon can confer copper resistance, we performed complementation assays in which a CopA-deficient E. coli W3110 strain was complemented with a plasmid harboring the S. pyogenes cop operon. Previous studies performed by Rensing et al. (31) showed that E. coli W3110ΔcopA contains a disrupted copA gene, making it deficient in a Cu(I)-translocating efflux pump, thus increasing its sensitivity to copper. S. pyogenes and E. coli W3110 CopA proteins exhibit ∼42% sequence identity and share conserved functional domains (Fig. 6A). Both CopA proteins have all the elements common to P-type ATPases as well as the distinct features of the heavy metal subgroup of CPx-type ATPases (17). Conserved features of these CopA proteins include a heavy metal-associated (HMA) domain characterized by an N-terminal CXXC sequence for copper binding. Also conserved are the following P-type ATPase functional components: a phosphatase domain (TGES), a putative copper channel (CPC), a phosphorylation domain (DKTGT), and an ATP binding region (GDGIN) (31). Although not highlighted in our sequence alignment, an additional feature common to all copper ATPases is the presence of eight transmembrane domains, which are necessary for anchorage of the protein in the cytoplasmic membrane (43). Sequence analysis (ClustalW2) revealed eight hydrophobic regions in S. pyogenes CopA with similarity to the eight transmembrane domains in E. coli CopA described previously (31). We cloned the cop operon promoter, copY, and copA into a plasmid backbone, pSU18::copYcopA, providing a functional copy of the copA gene (Fig. 6B). The promoter and copY gene were also provided to deal with the polycistronic nature of the S. pyogenes cop operon. PCR products from the complemented strain confirmed that S. pyogenes copA gene expression is responsive to copper exposure (Fig. 6C).

FIG 6.

CopA sequence alignment and expression of the S. pyogenes copA gene in a CopA-deficient E. coli mutant. (A) Conserved functional regions of the CopA amino acid sequences of E. coli W3110 (GenBank accession number WP_000083955.1) and MGAS5005 (accession number AAZ52023.1). Conserved residues (gray shading) and domains are shown (hatched boxes, heavy metal-associated domain [HMA]; black boxes, ATPase domains, with specific domains highlighted by black strips). E. coli CopA amino acids 121 to 232, 414 to 472, and 534 to 710 and S. pyogenes amino acids 51 to 263, 325 to 382, 444 to 621, and 683 to 678 were removed to focus on conserved regions. (B) To construct pSU18 containing the S. pyogenes cop operon, pSU18 was double digested (KpnI/XbaI) and ligated with PCR-amplified MGAS5005 copY and copA genes plus a 211-bp region upstream of copY, creating pSU18::copYcopA. E. coli W3110ΔcopA with pSU18::copYcopA was transformed prior to heterologous expression assays. Other features depicted on the plasmid include the chloramphenicol (cat) promoter, chloramphenicol resistance gene (CmR), origin of replication (p15A ori), catabolite activator protein (CAP) binding site, lactose (lac) promoter, lac operator, and M13 FWD/REV primer sequences. (C) PCR of E. coli W3110ΔcopA, E. coli W3110ΔcopA containing the control vector pSU18, and E. coli W3110ΔcopA containing pSU18::copYcopA. S. pyogenes MGAS5005 copA internal FWD/REV primers (159 bp) (top) and internal E. coli W3110 recA FWD/REV primers (159 bp) (bottom) were used to verify the expression of MGAS5005 copA in the E. coli mutant strain transformed with pSU18::copYcopA. L, 100-bp ladder; gDNA, genomic DNA.

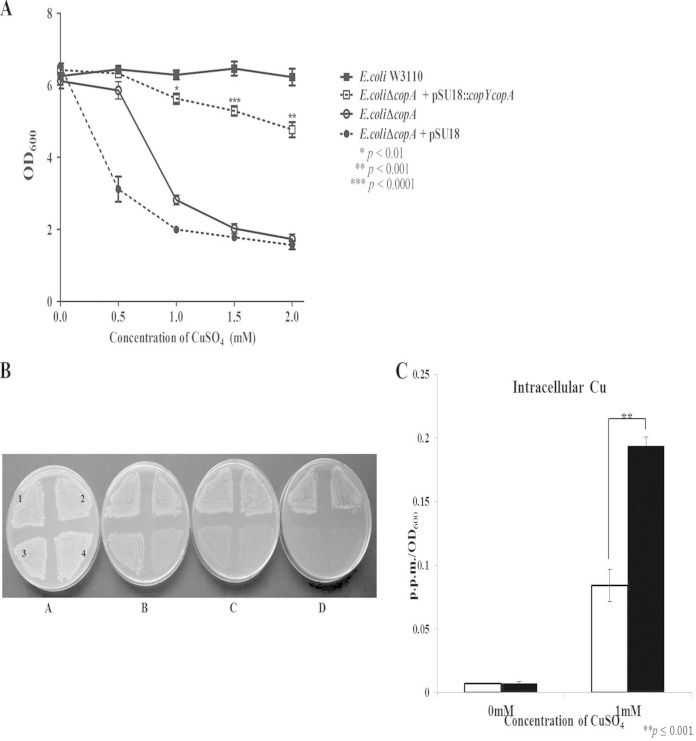

E. coli W3110ΔcopA containing the S. pyogenes cop operon had significantly increased resistance to copper compared to the CopA-deficient E. coli strain when grown in liquid culture or on plates (Fig. 7A and B) and had an ∼2-fold-lower total intracellular copper content than did the vector-only strain (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that S. pyogenes CopA may have a key role in controlling intracellular copper levels, by either promoting export or decreasing import.

FIG 7.

The S. pyogenes cop operon provides protection in a copper-sensitive E. coli W3110ΔcopA mutant. (A) Subcultures of wild-type E. coli W3110, W3110ΔcopA, and W3110ΔcopA containing pSU18::copYcopA or the vector control were incubated with CuSO4 at the indicated concentrations and grown aerobically for 8 h. Results are presented as means ± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments (P values represent the comparison of W3110ΔcopA containing pSU18::copYcopA to W3110ΔcopA at their respective CuSO4 concentrations; P values were determined by an unpaired t test). (B) Strains were plated onto LB plates containing increasing concentrations of CuSO4 (A, 0 mM; B, 1 mM; C, 2 mM; D, 3 mM). Section 1, wild-type E. coli W3110; section 2, E. coli W3110ΔcopA containing pSU18::copYcopA; section 3, E. coli W3110ΔcopA; section 4, E. coli W3110ΔcopA containing the control vector pSU18. The photograph is a representative image from three independent experiments. (C) Intracellular copper concentrations were measured via ICP-OES for E. coli W3110ΔcopA containing pSU18::copYcopA (white bars) and E. coli W3110ΔcopA containing the control vector pSU18 (black bars). Strains were grown for 8 h in the absence or presence of 1 mM CuSO4. Intracellular copper was measured in parts per million, and values were normalized to the optical densities of the samples. Data are representative of means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments (P values were determined by an unpaired t test).

DISCUSSION

The major goal of this study was to determine the mechanism(s) by which S. pyogenes protects against the toxic effects of copper. S. pyogenes is a member of the Firmicutes, a family in which only half of the members are thought to encode copper-containing enzymes (8, 48). Solioz et al. termed the members of this family that contain these cuproenzymes “users” and the members without these cuproenzymes “nonusers” (8). As there are no known users in Firmicutes of the order Lactobacillales (8), we hypothesized that the S. pyogenes copper system might actually be a method of copper resistance. Our studies revealed that growth in the presence of low copper levels is temporarily impaired, yet compensatory mechanisms are set in motion, which return growth to normal levels. However, higher concentrations of copper result in bacterial death. These results are consistent with the notion that an elevation of extracellular copper levels initiates a protective program in S. pyogenes that reaches maximum capacity as the concentration of copper reaches a critical level (>75 μM). In studies involving Mycobacterium tuberculosis macrophage infections, copper levels increased up to several hundred micromoles per liter within the phagolysosome (49). The induced expression of the S. pyogenes cop operon was well within this range.

Data from complementation assays utilizing an E. coli CopA-deficient strain strongly support the conclusion that S. pyogenes CopA can play a role in the control of intracellular copper levels by either mediating copper export or impairing copper entry. S. pyogenes CopA and E. coli CopA shared 42% sequence identity, and both proteins possessed the domains necessary for ATPase function. A critical feature of CopA function is the presence of transmembrane domains, which allow the protein to anchor in the cytoplasmic membrane (43). Sequence analysis revealed eight hydrophobic regions in S. pyogenes CopA with similarity to the eight transmembrane domains previously identified in E. coli CopA (31). The conserved nature of these domains suggests that S. pyogenes CopA expressed in an E. coli CopA-deficient mutant can function by anchoring in the cytoplasmic membrane and regulating intracellular copper levels in a manner similar to that of E. coli CopA.

We observed a significant increase in total intracellular copper levels in an E. coli CopA-deficient mutant compared to CopA-expressing strains. Given that bacteria are known to tightly regulate the amount of free cytoplasmic copper, it would be interesting in future studies to quantify free versus chelated cytoplasmic copper in a CopA-deficient strain compared to its parent strain. One would predict that as a CopA-deficient strain is exposed to increasing levels of copper, the amount of free cytoplasmic copper would increase in comparison to the amount chelated copper as the bacterium's defense mechanisms reach capacity and are unable to handle excess copper.

We recognize that this assay is not as definitive as directly testing the copper sensitivity of a GAS copA mutant. Although we used a range of methods to obtain a copA mutant of MGAS5005 (including standard GAS transformation techniques [50] as well as a new protocol involving the transformation of GAS in biofilms [51]), we were unable to obtain an appropriate mutant. However, Dao et al. reported the construction of a copA mutant in a different strain of GAS, HSC5 (52). Given that GAS has several metal transporters with potential redundancy in function with that of CopA (for example, PmtA [Spy_1167] [26], MtsABC [Spy_0368 to Spy_0370] [53], CutC [Spy_0337] [54, 55], and CzcD [Spy_0653] [56]), if the expression of one of these proteins is dominant in a given strain, isolation of a mutant for this dominant protein may be unlikely if the function of this protein is critical to the growth and survival of the organism. In view of our inability to obtain a copA mutant, we hypothesized that CopA may be such a dominant protein in MGAS5005. To address this notion, we searched two independent transposon mutant libraries containing single mutants that were prepared by K. S. McIver for strain 5448 (M1T1) (57) and by M. N. Neely for HSC5 (M14) (58). In strain 5448, a copA mutant was identified, whereas in strain HSC5, a copA mutant was not present. Even within a strain maintained in independent laboratories, there is potential for variability in the expression of specific genes. This strain variation may be responsible for the reported differences in the ability to generate copA mutants of HSC5 (52, 58). Nonetheless, we accept the possibility that copA mutants are present in a given library but have not yet been identified or that the technique used did not provide full genome coverage and thus was insufficient for targeting copA. Further supporting the possibility that strain variation accounts for these differences, there is a mutation in the covS gene in MGAS5005 (59) that is not present in strains 5448 (60) and HSC5 (61). Considering that a mutation in the CovRS two-component system has been shown to alter the transcriptome pattern of at least 10% of the genes in the genome of MGAS5005 (59), this background may be responsible for the difference in CopA as a putative dominant transporter in this strain.

Although GAS CopA shows homology to other copper exporters, how copper enters the bacterium has not been fully characterized. Studies involving copper users indicate the presence of specific importers in these bacteria (8, 62). To date, importers have not been identified in nonusers (8). Since we hypothesize that S. pyogenes is a nonuser of copper, copper may gain entry by one or more importers involved in the translocation of other metal ions. Once inside the cell, copper sequestration may operate in a manner that protects against inappropriate interactions with specific cellular components (63). CopZ, a copper chaperone, is a copper binding protein that shuttles copper to CopY or CopA for changes in gene expression or efflux (34, 38). In this regard, our analysis of the MGAS5005 genome revealed two genes located at chromosomal regions separate from the cop operon that were homologous to copper proteins. One gene encodes a putative “copper chaperone” (Spy_1403), and the second encodes a putative “copper homeostasis chaperone,” annotated cutC (Spy_0337). Spy_1403 encodes a short, 56-amino-acid protein that contains no relevant conserved domains, such as the heavy metal binding domain found in CopZ (64). Currently, the functions of Spy_1403 and S. pyogenes CutC are unknown. In E. coli, cutC has been shown to be one of the six genes (cutA to cutF) involved in copper transport and encodes a cytoplasmic protein of 146 amino acids (54). Furthermore, a cutC mutant strain of E. coli accumulates intracellular copper, making it more sensitive to copper-mediated killing (54). S. pyogenes CutC has 35% amino acid identity to E. coli CutC. These proteins in S. pyogenes require additional studies to determine whether they play a critical role in copper regulation. Although it is not known if S. pyogenes possesses a mechanism for sequestering copper, CutC might be a reasonable candidate. Additional sequestering mechanisms include siderophores, small molecules used to acquire iron (65), and the antioxidant glutathione (GSH) (66, 67). S. pyogenes is not known to produce siderophores and does not appear to have genes encoding homologues of siderophore production systems (68–70). S. pyogenes does not appear to synthesize GSH but, similar to other streptococcal species, may obtain it from the local environment (71, 72). Additional studies on the potential involvement of GSH in the protective anticopper response of S. pyogenes are clearly merited. These sequestering systems are highly important in the virulence of bacteria, as the host has its own mechanisms to synergistically induce ROS, deplete thiols, and increase concentrations of copper, which are sufficient for efficient killing of bacteria (73).

Our studies demonstrate that copper inhibits S. pyogenes biofilm formation, but established biofilms protect S. pyogenes from copper-mediated killing. These results raise several important questions. For example, how does copper repress biofilm formation? How do biofilms provide protection against copper-mediated killing of S. pyogenes? The copper-mediated repression of biofilm formation has been seen with other Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus (74) and S. mutans (75). The addition of as little as 1 μM copper is able to inhibit S. aureus biofilm formation (74). The authors of that study suggested that the effect was due to copper repression of the positive biofilm regulators Agr and Sae (74). In S. mutans, copper exposure alters the expression of glucosyltransferase, a key enzyme necessary for the adhesion and formation of biofilms on the tooth surface (75). Although regulators such as Mga (76), Srv (32, 77–80), CodY (81), and the CovRS two-component system (76) have been implicated in S. pyogenes biofilm formation, the direct and indirect effects of copper on their regulation have not yet been evaluated. With regard to the effect of copper on biofilm initiation and copper sensitivity within biofilms, we favor the notion that during initial exposure to copper, the biofilm matrix may act as a constraint on copper accumulation either via the nonspecific binding of copper by biofilm components or, perhaps, by modulating the rapid expression of copper-protective mechanisms within the bacteria. Alternatively, one could argue that biofilm formation results in the downregulation of one or more copper-protective expression programs in S. pyogenes. For example, in biofilms, S. pyogenes downregulates ∼40% of the genes involved in energy production and conversion compared to planktonic cultures grown to exponential phase (76). The reduced production of energy could negatively affect the ability of CopA, a CPx-type ATPase, to export copper and thus severely limit the ability of the bacteria to prevent intracellular copper levels from reaching a toxic threshold. We favor the notion that the combination of protection from biofilm matrix components and an altered program of gene expression is responsible for the overall protection of S. pyogenes biofilms against increasing concentrations of extracellular copper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all members of the Reid laboratory for their assistance and helpful comments. In addition, we thank the following individuals for their contributions to this research: Kevin McIver (University of Maryland) for supplying the chemically defined medium, allowing us to search his transposon library, and reviewing the manuscript; M. N. Neely (Wayne State University) for allowing us to search her transposon library and for reviewing the manuscript; Christopher Rensing (University of Copenhagen) and Barry Rosen (Florida International University) for donating the E. coli W3110 strains; Marc Solioz (University of Berne) for providing the pSU18 vector; and Patricia Dos Santos (Department of Chemistry) for guidance with ICP-OES. We also thank Steven B. Mizel (Department of Microbiology and Immunology) for his help in the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Affiliate grant 11GRNT7980017.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cunningham MW. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 13:470–511. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.3.470-511.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham MW. 2008. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections and their sequelae. Adv Exp Med Biol 609:29–42. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73960-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisno AL, Brito MO, Collins CM. 2003. Molecular basis of group A streptococcal virulence. Lancet Infect Dis 3:191–200. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00576-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erickson KL, Medina EA, Hubbard NE. 2000. Micronutrients and innate immunity. J Infect Dis 182(Suppl 1):S5–S10. doi: 10.1086/315922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricci S, Janulczyk R, Bjorck L. 2002. The regulator PerR is involved in oxidative stress response and iron homeostasis and is necessary for full virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun 70:4968–4976. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.4968-4976.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weston BF, Brenot A, Caparon MG. 2009. The metal homeostasis protein, Lsp, of Streptococcus pyogenes is necessary for acquisition of zinc and virulence. Infect Immun 77:2840–2848. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01299-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahesh S, Nizet V, Cole JN. 2012. Study of streptococcal hemoprotein receptor (Shr) in iron acquisition and virulence of M1T1 group A streptococcus. Virulence 3:566–575. doi: 10.4161/viru.21933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solioz M, Abicht HK, Mermod M, Mancini S. 2010. Response of gram-positive bacteria to copper stress. J Biol Inorg Chem 15:3–14. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magnani D, Solioz M. 2007. How bacteria handle copper, p 259–285. In Nies DH, Silver S (ed), Molecular microbiology of heavy metals. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frausto da Silva JJR, Williams RJP. 1993. The biological chemistry of the elements, 2nd ed Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker KW, Skaar EP. 2014. Metal limitation and toxicity at the interface between host and pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Rev 38:1235–1249. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porcheron G, Garenaux A, Proulx J, Sabri M, Dozois CM. 2013. Iron, copper, zinc, and manganese transport and regulation in pathogenic enterobacteria: correlations between strains, site of infection and the relative importance of the different metal transport systems for virulence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:90. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shafeeq S, Yesilkaya H, Kloosterman TG, Narayanan G, Wandel M, Andrew PW, Kuipers OP, Morrissey JA. 2011. The cop operon is required for copper homeostasis and contributes to virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 81:1255–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vats N, Lee SF. 2001. Characterization of a copper-transport operon, copYAZ, from Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 147:653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnani D, Barre O, Gerber SD, Solioz M. 2008. Characterization of the CopR regulon of Lactococcus lactis IL1403. J Bacteriol 190:536–545. doi: 10.1128/JB.01481-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solioz M, Stoyanov JV. 2003. Copper homeostasis in Enterococcus hirae. FEMS Microbiol Rev 27:183–195. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solioz M, Vulpe C. 1996. CPx-type ATPases: a class of P-type ATPases that pump heavy metals. Trends Biochem Sci 21:237–241. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(96)20016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward SK, Abomoelak B, Hoye EA, Steinberg H, Talaat AM. 2010. CtpV: a putative copper exporter required for full virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 77:1096–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwan WR, Warrener P, Keunz E, Stover CK, Folger KR. 2005. Mutations in the cueA gene encoding a copper homeostasis P-type ATPase reduce the pathogenicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice. Int J Med Microbiol 295:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis MS, Thomas CJ. 1997. Mutants in the CtpA copper transporting P-type ATPase reduce virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Microb Pathog 22:67–78. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osman D, Waldron KJ, Denton H, Taylor CM, Grant AJ, Mastroeni P, Robinson NJ, Cavet JS. 2010. Copper homeostasis in Salmonella is atypical and copper-CueP is a major periplasmic metal complex. J Biol Chem 285:25259–25268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson MD, Kehl-Fie TE, Klein R, Kelly J, Burnham C, Mann B, Rosch JW. 2015. Role of copper efflux in pneumococcal pathogenesis and resistance to macrophage-mediated immune clearance. Infect Immun 83:1684–1694. doi: 10.1128/IAI.03015-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsatsaronis JA, Walker MJ, Sanderson-Smith ML. 2014. Host responses to group A streptococcus: cell death and inflammation. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004266. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Condon S. 1987. Responses of lactic acid bacteria to oxygen. FEMS Microbiol Rev 46:269–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1987.tb02465.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiSilvestro RA. 1989. Effects of inflammation on copper antioxidant enzyme levels. Adv Exp Med Biol 258:253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenot A, Weston BF, Caparon MG. 2007. A PerR-regulated metal transporter (PmtA) is an interface between oxidative stress and metal homeostasis in Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol 63:1185–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid SD, Hoe NP, Smoot LM, Musser JM. 2001. Group A Streptococcus: allelic variation, population genetics, and host-pathogen interactions. J Clin Invest 107:393–399. doi: 10.1172/JCI11972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musser JM, Krause RM. 1998. The revival of group A streptococcal diseases, with a commentary on staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, p 185–218. In Krause RM. (ed), Emerging infections, vol 1 Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gera K, McIver KS. 2013. Laboratory growth and maintenance of Streptococcus pyogenes (the group A Streptococcus, GAS). Curr Protoc Microbiol 30:Unit 9D.2. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc09d02s30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen KF. 1993. The Escherichia coli K-12 “wild types” W3110 and MG1655 have an rph frameshift mutation that leads to pyrimidine starvation due to low pyrE expression levels. J Bacteriol 175:3401–3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rensing C, Fan B, Sharma R, Mitra B, Rosen BP. 2000. CopA: an Escherichia coli Cu(I)-translocating P-type ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:652–656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doern CD, Roberts AL, Hong W, Nelson J, Lukomski S, Swords WE, Reid SD. 2009. Biofilm formation by group A Streptococcus: a role for the streptococcal regulator of virulence (Srv) and streptococcal cysteine protease (SpeB). Microbiology 155:46–52. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.021048-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed, vol 1 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magnani D, Solioz M. 2005. Copper chaperone cycling and degradation in the regulation of the cop operon of Enterococcus hirae. Biometals 18:407–412. doi: 10.1007/s10534-005-3715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Portmann R, Magnani D, Stoyanov JV, Schmechel A, Multhaup G, Solioz M. 2004. Interaction kinetics of the copper-responsive CopY repressor with the cop promoter of Enterococcus hirae. J Biol Inorg Chem 9:396–402. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portmann R, Poulsen KR, Wimmer R, Solioz M. 2006. CopY-like copper inducible repressors are putative ‘winged helix’ proteins. Biometals 19:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s10534-005-5381-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pecou E, Maass A, Remenik D, Briche J, Gonzalez M. 2006. A mathematical model for copper homeostasis in Enterococcus hirae. Math Biosci 203:222–239. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cobine P, Wickramasinghe WA, Harrison MD, Weber T, Solioz M, Dameron CT. 1999. The Enterococcus hirae copper chaperone CopZ delivers copper(I) to the CopY repressor. FEBS Lett 445:27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strausak D, Solioz M. 1997. CopY is a copper-inducible repressor of the Enterococcus hirae copper ATPases. J Biol Chem 272:8932–8936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.8932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fu Y, Tsui HC, Bruce KE, Sham LT, Higgins KA, Lisher JP, Kazmierczak KM, Maroney MJ, Dann CE III, Winkler ME, Giedroc DP. 2013. A new structural paradigm in copper resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nat Chem Biol 9:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reyes A, Leiva A, Cambiazo V, Mendez MA, Gonzalez M. 2006. Cop-like operon: structure and organization in species of the Lactobacillale order. Biol Res 39:87–93. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602006000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Odermatt A, Suter H, Krapf R, Solioz M. 1993. Primary structure of two P-type ATPases involved in copper homeostasis in Enterococcus hirae. J Biol Chem 268:12775–12779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raimunda D, Gonzalez-Guerrero M, Leeber BW III, Arguello JM. 2011. The transport mechanism of bacterial Cu+-ATPases: distinct efflux rates adapted to different function. Biometals 24:467–475. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9404-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez-Guerrero M, Raimunda D, Cheng X, Arguello JM. 2010. Distinct functional roles of homologous Cu+ efflux ATPases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 78:1246–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts AL, Connolly KL, Kirse DJ, Evans AK, Poehling KA, Peters TR, Reid SD. 2012. Detection of group A Streptococcus in tonsils from pediatric patients reveals high rate of asymptomatic streptococcal carriage. BMC Pediatr 12:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hidalgo-Grass C, Dan-Goor M, Maly A, Eran Y, Kwinn LA, Nizet V, Ravins M, Jaffe J, Peyser A, Moses AE, Hanski E. 2004. Effect of a bacterial pheromone peptide on host chemokine degradation in group A streptococcal necrotising soft-tissue infections. Lancet 363:696–703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15643-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takemura N, Noiri Y, Ehara A, Kawahara T, Noguchi N, Ebisu S. 2004. Single species biofilm-forming ability of root canal isolates on gutta-percha points. Eur J Oral Sci 112:523–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2004.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ridge PG, Zhang Y, Gladyshev VN. 2008. Comparative genomic analyses of copper transporters and cuproproteomes reveal evolutionary dynamics of copper utilization and its link to oxygen. PLoS One 3:e1378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner D, Maser J, Lai B, Cai Z, Barry CE III, Honer Zu Bentrup K, Russell DG, Bermudez LE. 2005. Elemental analysis of Mycobacterium avium-, Mycobacterium tuberculosis-, and Mycobacterium smegmatis-containing phagosomes indicates pathogen-induced microenvironments within the host cell's endosomal system. J Immunol 174:1491–1500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Breton Y, McIver KS. 2013. Genetic manipulation of Streptococcus pyogenes (the group A Streptococcus, GAS). Curr Protoc Microbiol 30:Unit 9D.3. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc09d03s30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marks LR, Mashburn-Warren L, Federle MJ, Hakansson AP. 2014. Streptococcus pyogenes biofilm growth in vitro and in vivo and its role in colonization, virulence, and genetic exchange. J Infect Dis 210:25–34. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dao TH, Johnson MD, Rosch JW. 2014. Role of copper homeostasis in the pathogenesis of Streptococcus pyogenes, p 148 Abstr 114th Gen Meet Am Soc Microbiol, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janulczyk R, Pallon J, Bjorck L. 1999. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes ABC transporter with multiple specificity for metal cations. Mol Microbiol 34:596–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta SD, Lee BT, Camakaris J, Wu HC. 1995. Identification of cutC and cutF (nlpE) genes involved in copper tolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 177:4207–4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Latorre M, Olivares F, Reyes-Jara A, Lopez G, Gonzalez M. 2011. CutC is induced late during copper exposure and can modify intracellular copper content in Enterococcus faecalis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 406:633–637. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anton A, Grosse C, Reissmann J, Pribyl T, Nies DH. 1999. CzcD is a heavy metal ion transporter involved in regulation of heavy metal resistance in Ralstonia sp. strain CH34. J Bacteriol 181:6876–6881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Le Breton Y, Mistry P, Valdes KM, Quigley J, Kumar N, Tettelin H, McIver KS. 2013. Genome-wide identification of genes required for fitness of group A Streptococcus in human blood. Infect Immun 81:862–875. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00837-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kizy AE, Neely MN. 2009. First Streptococcus pyogenes signature-tagged mutagenesis screen identifies novel virulence determinants. Infect Immun 77:1854–1865. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01306-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sumby P, Whitney AR, Graviss EA, DeLeo FR, Musser JM. 2006. Genome-wide analysis of group A streptococci reveals a mutation that modulates global phenotype and disease specificity. PLoS Pathog 2:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kansal RG, Datta V, Aziz RK, Abdeltawab NF, Rowe S, Kotb M. 2010. Dissection of the molecular basis for hypervirulence of an in vivo-selected phenotype of the widely disseminated M1T1 strain of group A Streptococcus bacteria. J Infect Dis 201:855–865. doi: 10.1086/651019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kang SO, Wright JO, Tesorero RA, Lee H, Beall B, Cho KH. 2012. Thermoregulation of capsule production by Streptococcus pyogenes. PLoS One 7:e37367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim HJ, Graham DW, DiSpirito AA, Alterman MA, Galeva N, Larive CK, Asunskis D, Sherwood PM. 2004. Methanobactin, a copper-acquisition compound from methane-oxidizing bacteria. Science 305:1612–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.1098322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harrison MD, Jones CE, Solioz M, Dameron CT. 2000. Intracellular copper routing: the role of copper chaperones. Trends Biochem Sci 25:29–32. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arnesano F, Banci L, Bertini I, Cantini F, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Huffman DL, O'Halloran TV. 2001. Characterization of the binding interface between the copper chaperone Atx1 and the first cytosolic domain of Ccc2 ATPase. J Biol Chem 276:41365–41376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104807200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garenaux A, Dozois CM. 2012. Metals: ironing out copper toxicity. Nat Chem Biol 8:680–681. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gopal S, Borovok I, Ofer A, Yanku M, Cohen G, Goebel W, Kreft J, Aharonowitz Y. 2005. A multidomain fusion protein in Listeria monocytogenes catalyzes the two primary activities for glutathione biosynthesis. J Bacteriol 187:3839–3847. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.11.3839-3847.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Masip L, Veeravalli K, Georgiou G. 2006. The many faces of glutathione in bacteria. Antioxid Redox Signal 8:753–762. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beres SB, Sylva GL, Barbian KD, Lei B, Hoff JS, Mammarella ND, Liu MY, Smoot JC, Porcella SF, Parkins LD, Campbell DS, Smith TM, McCormick JK, Leung DY, Schlievert PM, Musser JM. 2002. Genome sequence of a serotype M3 strain of group A Streptococcus: phage-encoded toxins, the high-virulence phenotype, and clone emergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:10078–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152298499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smoot JC, Barbian KD, Van Gompel JJ, Smoot LM, Chaussee MS, Sylva GL, Sturdevant DE, Ricklefs SM, Porcella SF, Parkins LD, Beres SB, Campbell DS, Smith TM, Zhang Q, Kapur V, Daly JA, Veasy LG, Musser JM. 2002. Genome sequence and comparative microarray analysis of serotype M18 group A Streptococcus strains associated with acute rheumatic fever outbreaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:4668–4673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062526099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ferretti JJ, McShan WM, Ajdic D, Savic DJ, Savic G, Lyon K, Primeaux C, Sezate S, Suvorov AN, Kenton S, Lai HS, Lin SP, Qian Y, Jia HG, Najar FZ, Ren Q, Zhu H, Song L, White J, Yuan X, Clifton SW, Roe BA, McLaughlin R. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:4658–4663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071559398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Janowiak BE, Griffith OW. 2005. Glutathione synthesis in Streptococcus agalactiae. One protein accounts for gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase and glutathione synthetase activities. J Biol Chem 280:11829–11839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Potter AJ, Trappetti C, Paton JC. 2012. Streptococcus pneumoniae uses glutathione to defend against oxidative stress and metal ion toxicity. J Bacteriol 194:6248–6254. doi: 10.1128/JB.01393-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kashyap DR, Rompca A, Gaballa A, Helmann JD, Chan J, Chang CJ, Hozo I, Gupta D, Dziarski R. 2014. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins kill bacteria by inducing oxidative, thiol, and metal stress. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004280. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baker J, Sitthisak S, Sengupta M, Johnson M, Jayaswal RK, Morrissey JA. 2010. Copper stress induces a global stress response in Staphylococcus aureus and represses sae and agr expression and biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:150–160. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02268-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen PM, Chen JY, Chia JS. 2006. Differential regulation of Streptococcus mutans gtfBCD genes in response to copper ions. Arch Microbiol 185:127–135. doi: 10.1007/s00203-005-0076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cho KH, Caparon MG. 2005. Patterns of virulence gene expression differ between biofilm and tissue communities of Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol 57:1545–1556. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Connolly KL, Braden AK, Holder RC, Reid SD. 2011. Srv mediated dispersal of streptococcal biofilms through SpeB is observed in CovRS+ strains. PLoS One 6:e28640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Connolly KL, Roberts AL, Holder RC, Reid SD. 2011. Dispersal of group A streptococcal biofilms by the cysteine protease SpeB leads to increased disease severity in a murine model. PLoS One 6:e18984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roberts AL, Connolly KL, Doern CD, Holder RC, Reid SD. 2010. Loss of the group A Streptococcus regulator Srv decreases biofilm formation in vivo in an otitis media model of infection. Infect Immun 78:4800–4808. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00255-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roberts AL, Holder RC, Reid SD. 2010. Allelic replacement of the streptococcal cysteine protease SpeB in a Deltasrv mutant background restores biofilm formation. BMC Res Notes 3:281. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McDowell EJ, Callegari EA, Malke H, Chaussee MS. 2012. CodY-mediated regulation of Streptococcus pyogenes exoproteins. BMC Microbiol 12:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]