Abstract

Background

A study was conducted to investigate (1) the extent to which best-practice central line maintenance practices were employed in the homes of pediatric oncology patients and by whom, (2) caregiver beliefs about central line care and central line–associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) risk, (3) barriers to optimal central line care by families, and (4) educational experiences and preferences regarding central line care.

Methods

Researchers administered a survey to patients and families in a tertiary care pediatric oncology clinic that engaged in rigorous ambulatory and inpatient CLABSI prevention efforts.

Results

Of 110 invited patients and caregivers, 105 participated (95% response rate) in the survey (March–May 2012). Of the 50 respondents reporting that they or another caregiver change central line dressings, 48% changed a dressing whenever it was soiled as per protocol (many who did not change dressings per protocol also never personally changed dressings); 67% reported the oncology clinic primarily cares for their child’s central line, while 29% reported that an adult caregiver or the patient primarily cares for the central line. Eight patients performed their own line care “always” or “most of the time.” Some 13% of respondents believed that it was “slightly likely” or “not at all likely” that their child will get an infection if caregivers do not perform line care practices perfectly every time. Dressing change practices were the most difficult to comply with at home. Some 18% of respondents wished they learned more about line care, and 12% received contradictory training. Respondents cited a variety of preferences regarding line care teaching, although the majority looked to clinic nurses for modeling line care.

Conclusions

Interventions aimed at reducing ambulatory CLABSIs should target appropriate educational experiences for adult caregivers and patients and identify ways to improve compliance with best-practice care.

A typical pediatric central line–associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) costs up to $55,646 and increases length of stay by 19 days.1 Children with cancer diagnoses are at a 3.7-to-5 times greater risk of CLABSI than children without cancer, 1 and pediatric hematology/oncology patients and pediatric bone marrow transplant patients have higher CLABSI rates then almost all subsets of comparable adult oncology patients.2 Research suggests that three times as many CLABSIs occur in the ambulatory pediatric oncology setting than in the inpatient pediatric oncology setting and that these infections lead to appreciable morbidity.3–5 For example, 44% of central lines are removed and 13%–17% of patients have ICU admissions following ambulatory CLABSIs.3–5

Reduction of ambulatory pediatric oncology CLABSIs is challenging, as ambulatory central lines are maintained by a diverse group of providers, including clinic staff, home health care agencies, families, and patients. Decreased ambulatory CLABSI rates have been demonstrated after implementing central line maintenance care bundles that include families and patients as key participants.4 These maintenance care bundles, which are based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations6 and previous oncology CLABSI work,7,8 focus on (1) reducing entries into the line, (2) creating awareness of line problems, (3) aseptic entries into the line, and (4) aseptic procedures when changing line components.4 Bundles are currently regarded as “best practices” for reducing CLABSIs, although individual elements have not been tested for efficacy.

Prior work has suggested that home health care agencies’ policies vary from best-practice line care9 but that variation from and barriers to effective family implementation of best-practice central line maintenance care are unknown and must be investigated to maximize compliance by mostly nonmedically trained caregivers. For example, Møller et al. found that more than 85% of 42 patients were able to complete a central line care educational intervention; this intervention reduced CLABSIs by 50% in a small, single-center randomized controlled trial of adult patients with hematologic malignancies.10 A different group of adult oncology patients identified appreciable differences in clinic nurse central line care practices, and these patients reported variations in central line maintenance practices in their home setting.11 It is unclear if results for adults can be translated to the unique setting presented by pediatric oncology patients, where an adult caregiver and the patient together often provide central line care, and multiple stressors contribute to quality of life.12

Ambulatory CLABSI prevention is paramount as medical advances allow more children to live at home with long-term central lines, and yet little is known about how pediatric patients and their families take care of central lines and want to be educated about central line care. In the study reported in this article, we used researcher-administered surveys to investigate (1) the extent to which best-practice central line maintenance was employed in the pediatric oncology home and by whom, (2) caregiver beliefs about central line care and CLABSI risk, (3) barriers to best-practice family central line care, and (4) educational experiences and preferences regarding central line care. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining caregiver practices and perceptions of ambulatory pediatric oncology central line care, and these results can inform interventions aimed at eliminating CLABSIs in ambulatory pediatric oncology patients.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted at an urban, tertiary care, university-affiliated, pediatric hospital. The pediatric oncology division sees approximately 200 patients with new oncologic diagnoses, performs 35 stem cell transplants, and conducts 7,000 clinic visits annually. Approximately 110 to 140 pediatric oncology patients have central lines in place at any given time. The survey was conducted in the pediatric oncology clinic from March through May 2012.

An inpatient oncology CLABSI reduction effort was begun at our institution in November 2009,4,8 and an ambulatory oncology CLABSI reduction effort was begun in December 2010.4 Families were incorporated into both of these efforts by empowering them to stop inappropriate central line care by any staff member, educating them on best-practice care bundles, standardizing education across the inpatient and ambulatory arenas, and performing family return-demonstrations of central line maintenance care for those patients who regularly flushed central lines or delivered medications at home. Teaching efforts regarding central line care were focused on the central line maintenance care bundle as described, and at least quarterly meetings were held between inpatient, ambulatory, and home care nurses to standardize topics taught. Standard handouts and information packets were available to nurses for teaching patients and families, although no official, audited curriculum was implemented.

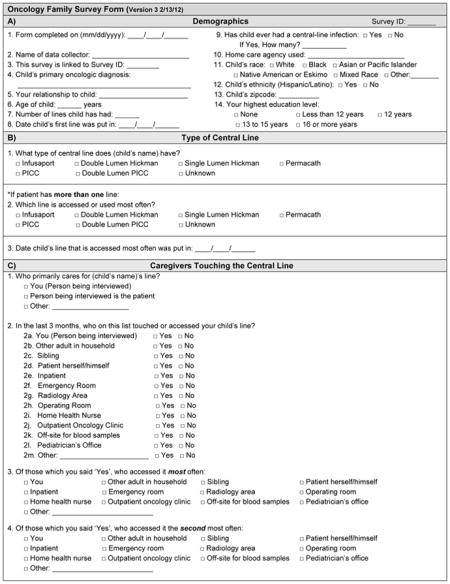

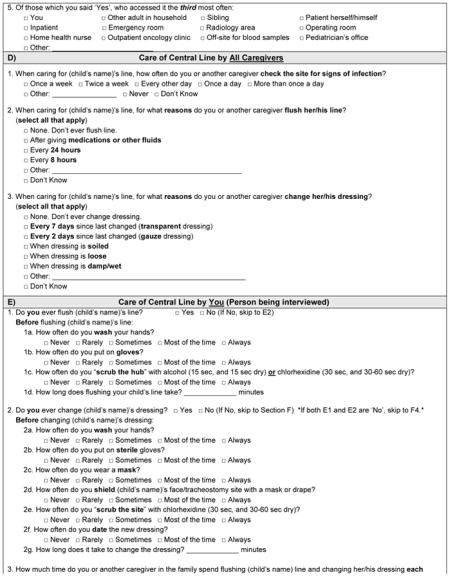

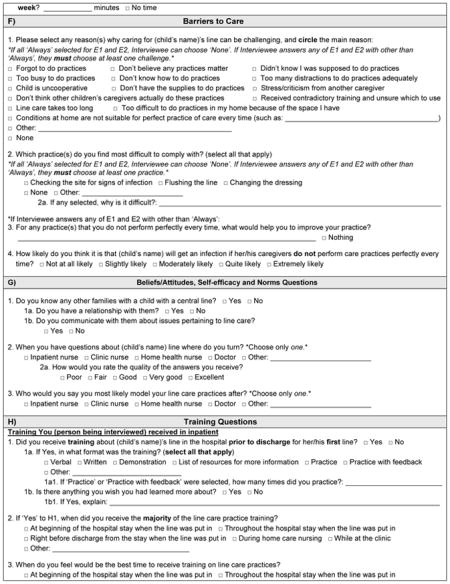

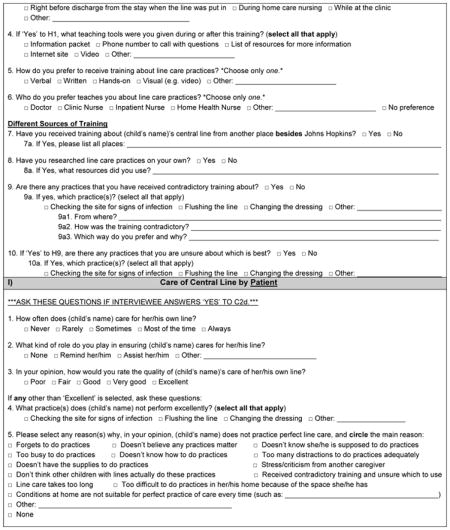

Survey Development and Administration

A 50-question survey was developed and pilot tested with nine pediatric oncology patient families. The pilot results were not included in the final results. During the researcher-administered survey, a research assistant verbally asked adult caregivers or patients older than 17 years of age about (1) demographics (patient’s age, race, ethnicity, oncologic diagnosis, central line type and infection history; respondent’s relationship to the child and educational level); (2) central line care by the adult caregiver and patient regardless of age, and caregivers touching the central line; (3) caregiver beliefs about central line care; (4) barriers to central line care; and (5) central line care education experiences and preferences. To target future educational efforts about central line care, it is important to understand who accesses and maintains central lines in the home setting and hence, the survey included questions on caregivers touching the central line. It also asked about self-reported central line care at home to understand the current practices of caregivers in the home setting. Finally, it asked about barriers to care and previous educational experiences to improve central line care education for family and patient caregivers.

Central line care items were based on the Children’s Hospital Association hematology/oncology central line maintenance care bundle,4,8 and had been standard practice in our clinic for more than one year.4 As part of the clinic’s efforts to reduce ambulatory CLABSIs, families who handled central lines in the home performed quarterly return-demonstrations of central line care.4 Five-point Likert scales were used to investigate frequency of central line care practices (never, rarely, sometimes, most of the time, always), likelihood of infection (not at all likely, slightly likely, moderately likely, quite likely, extremely likely), and quality of education and patient’s line care (poor, fair, good, very good, excellent). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Johns Hopkins University.13 The verbal survey took approximately 30 to 40 minutes to complete and was at a 5.0 Flesh-Kincaid grade level for readability. Large visual aids were presented to help participants understand, remember, and choose multiple-choice options. Participants received a $10 inducement in the form of a gift card. The complete survey is presented in Appendix 1 (available in online article).

Potential participants with central lines were identified by an oncology clinic charge nurse, and a research assistant approached participants following a predesigned script during downtimes in their clinic visit. The charge nurse was asked to identify any patient with a central line to the research assistant. To lessen the possibility of social desirability bias, the survey was administered by a research assistant from outside the pediatric oncology division, and emphasis was placed on informing potential participants that all responses were anonymous and would not affect their medical care in any way. A patient’s family could be surveyed only once, even if a different adult caregiver came to the clinic within the study window. After consent was obtained from adult caregivers, survey interviews were conducted in semiprivate areas, and questions to adult caregivers regarding a patient’s central line care were asked without the patient present.

Following the survey, respondents were asked if they had other questions about central line care and were offered either prepared written materials regarding line care or their primary clinic nurse for answers. Respondents who reported concerning answers during the survey were referred to their primary clinic nurse after obtaining permission from the respondent.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (means, medians, standard deviations) were used to analyze data. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess associations between perception of infection risk from central line care not performed perfectly “every time” and (1) previous self-reported central line infections and (2) respondent’s educational level. Patients with tunneled, externalized catheters were analyzed as a subgroup, as they are at higher risk of CLABSI5 and are responsible for accessing central lines at home more often. Data analyses were conducted in Stata 11.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). This project was approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Results

Respondent and Patient Demographics

Of the 110 patients and caregivers who were approached for participation, 106 agreed to participate, of whom 105 completed the entire survey (95% response rate). Eighty-seven respondents (83%) were parents of a patient, and most respondents (72%) had more than a high school education (Table 1, right). Patient demographics closely mirror a non–survey-based epidemiologic analysis of this oncology population.5 Forty-nine respondents (47%) reported the patient having more than one central line during the course of his or her treatment, and 15 (14%) reported that the patient had more than two central lines. Seven patients (7%) self-reported having one “central line infection,” 5 (5%) reported two “central line infections” and 2 (2%) reported more than two “central line infections.”

Table 1.

Respondent and Patient Demographics, Patient’s Central Line History, and Respondent’s Perception of Risk of Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI)

| Characteristic | No. of Respondents (%)N = 105 |

|---|---|

|

| |

|

Respondent’s Demographics

| |

| Respondent’s Relationship to the Patient | |

| Mother | 74 (70) |

| Self | 14 (13) |

| Father | 13 (12) |

| Grandparent | 3 (3) |

| Other | 1(1) |

|

| |

| Respondent’s Highest Educational Level | |

| 16 or more years | 48 (46) |

| 13–15 years | 28 (27) |

| 12 years | 23 (22) |

| Less than 12 years | 5 (5) |

| None | 1 (1) |

|

| |

| Patient’s Demographics | |

|

| |

| Mean Age of Patient in Years (SD) | 9 (5.9) |

|

| |

| Patient’s Race | |

| White | 71 (68) |

| Black | 19 (18) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 7 (7) |

| Mixed Race | 7 (7) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Native American or Eskimo | — |

|

| |

| Patient’s Ethnicity Not Hispanic | 96 (91) |

|

| |

| Patient’s Malignancy Type | |

| Hematologic | 61 (58) |

| Solid | 41 (39) |

| Nononcologic bone marrow transplant | 3 (3) |

|

| |

| Patients Not Using a Home Care Agency | 53 (50) |

|

| |

| Patient’s Central Line History | |

|

| |

| Median Number of Central Lines (IQR) | 1 (1, 2) |

|

| |

| Median Days Since Patient’s First Central Line Inserted (IQR) | 313 (163, 607) |

|

| |

| Current Central Line Type* | |

| Totally implantable devices | 91 (87) |

| Tunneled, externalized catheters | 14 (13) |

| Peripherally inserted central catheters | 3 (3) |

| Other | — |

|

| |

| Patients with a Self-Reported Central Line Infection | 14 (13) |

|

| |

| Respondent’s Perception of CLABSI Risk Without Perfect Line Care | |

| Extremely likely | 39 (37) |

| Quite likely | 27 (26) |

| Moderately likely | 25 (24) |

| Slightly likely | 13 (12) |

| Not at all likely | 1 (1) |

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

The percentages in this cell sum to > 100% because 3 patients had more than 1 central line: 1 totally implantable device and a peripherally inserted central catheter, and 2 totally implantable devices and tunneled, externalized catheters.

Best-Practice Central Line Care by All Caregivers

As per clinic protocol, 51 respondents (49%) reported that they or another caregiver check their child’s central line site for signs of infection daily, but 26 respondents (25%) reported checking for signs of infection twice a week or less frequently (Table 2, page 181). When asked for all reasons the respondent or another caregiver flushed the central line, 94 (90%) reported that they or another caregiver flush after medications or other fluids as per clinic protocol, but 5 (5%) were not sure when to flush. Of the 50 respondents who reported that they or another caregiver change their child’s central line dressing, 24 (48%) reported that they or another caregiver would change dressings when soiled, 28 (56%) when loose, 30 (60%) when wet/damp, as per our clinic’s protocol. Of note, many respondents who reported that they or another caregiver did not change dressings per protocol also reported that they personally never changed dressings: 24 respondents who did not change when soiled, 19 who did not change when loose, and 18 who did not change when wet/damp did not personally change dressings.

Table 2.

Central Line Practices by Reported Central Line Type*

| Totally Implantable Devices (TID)† | Tunneled, Externalized Catheters (TEC) | Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N = 89 (%) | N = 14 (%) | N = 2 (%) | |

|

| |||

| How often do you or another caregiver check the site for signs of infection? | |||

| Once a week or less frequently | 13 (15) | — | — |

| Twice a week | 12 (13) | — | — |

| Every other day | 9 (10) | 1 (7) | — |

| Once a day* | 40 (45) | 10 (71) | 1 (50) |

| More than once a day | 13 (15) | 3 (21) | 1 (50) |

| Never | 1 (1) | — | — |

| Don’t know | 1 (1) | — | — |

|

| |||

| For what reasons do you or another caregiver flush his or her line? (select all that apply) | |||

| None. Don’t ever flush line | — | — | — |

| After giving medications or other fluids* | 80 (90) | 12 (86) | 2 (100) |

| Every 24 hours (per protocol for TEC)* | N/A | 13 (93) | — |

| Every 8 hours (per protocol for PICC)* | N/A | — | 1 (50) |

| Don’t know | 5 (6) | — | — |

|

| |||

| For what reasons do you or another caregiver change his or her dressing? (select all that apply): Percentages based on number that “ever” change dressing | |||

| None. Don’t ever change dressing | 55 (62) | — | — |

| Every 7 days since last changed (transparent dressing) (per protocol for TEC and PICC)* | 14 (100) | ||

| 16 (47) | 2 (100) | ||

| Every 2 days since last changed (gauze dressing) | 1 (3) | — | — |

| When dressing is soiled* | 15 (44) | 8 (57) | 1 (50) |

| When dressing is loose* | 20 (59) | 7 (50) | 1 (50) |

| When dressing is damp/wet* | 20 (59) | 9 (64) | 1 (50) |

| Don’t know | 1 (3) | — | — |

|

| |||

| N = 11 (%) | N = 12 (%) | N = 2 (%) | |

|

| |||

| If respondent flushed his or her child’s line, before flushing the line: Answered “always” or “most of the time” | |||

| How often do you wash your hands?* | 11 (100) | 12 (100) | 2 (100) |

| How often do you put on gloves?* | 11 (100) | 9 (75) | 2 (100) |

| How often do you “scrub the hub” with alcohol (15-sec scrub and 15-sec dry) or chlorhexidine (30-sec scrub and 30–60-sec dry)?* | 10 (83) | ||

| 8 (73) | 1 (50) | ||

| How long does flushing your child’s line take? Mean in minutes (SD) | 4.3 (2) | 3.8 (3) | 4 (1) |

|

| |||

| N = 1 | N = 9 | N = 0 | |

|

| |||

| If respondent changed his or her child’s dressing, before changing the dressing: Answered “always” or “most of the time” | |||

| How often do you wash your hands?* | 1 (100) | 9 (100) | |

| How often do you put on sterile gloves?* | 1 (100) | 9 (100) | |

| How often do you wear a mask?* | 1 (100) | 9 (100) | |

| How often do you shield child’s face/tracheostomy site with a mask or drape?* | 1 (100) | 7 (78) | |

| How often do you “scrub the site” with chlorhexidine (30-sec scrub and 30–60-sec dry)?* | 1 (100) | 7 (78) | |

| How often do you date the new dressing?* | 1 (100) | 4 (44) | |

| How long does it take to change the dressing? Mean in minutes (SD) | 4 | 9.9 (8) | |

|

| |||

| How much time do you or another caregiver in the family spend flushing the child’s line and changing his or her dressing each week? Mean in minutes (SD) | 40.6 (32) | 92 (147) | 63 (59) |

SD, standard deviation.

Per clinic protocol.

As 3 patients had 2 central lines, these data are generated on the basis of the central line reported to be used most often.

Assessing the knowledge and understandings of caregivers who do not directly touch a child’s central line or dressing is of importance, as these caregivers serve as first responders in recognizing central line problems that could lead to a CLABSI; for example, if a patient’s dressing is soiled, these caregivers would choose whether to bring the patient in for a dressing change.

Best-Practice Central Line Care by Survey Respondents

Of the 25 respondents who reported that they personally flush their child’s central line, 22 (88%) always or most of the time wear gloves, and 19 (76%) always or most of the time scrub the hub with alcohol, all as per our clinic’s protocol (Table 2). Of the 10 respondents who reported that they personally change their child’s central line dressing, 8 (80%) always or most of the time scrub the site with chlorhexidine, and 5 (50%) always or most of the time date the dressing, all as per our clinic’s protocol. These respondents reported taking 4 minutes on average to flush their child’s central line, 9 minutes on average to change the dressing, and spending 66 minutes total per week flushing and/or changing dressings.

Best-Practice Central Line Care by Patient

Eight patients performed their own line care “always or most of the time,” and 7 of these patients were younger than 18 years of age (two 8-year-olds and one 11-, 12-, 15-, 16-, and 17-year-old each). Ten respondents’ children touched or accessed the central line at some point in the last three months, and 5 respondents saw their role in ensuring the child’s central line care as reminding the child, 4 saw their role as assisting their child, and 1 caregiver of an 11-year-old felt that she had no role in ensuring their child’s central line care. Of note, the clinic had no policy or standard regarding the role of parents in ensuring the child’s line care. Seven respondents felt that their child performs excellent central line care, including the caregivers of three 8-year-old patients. Of the 6 children who do not perform excellent line care, respondents reported that 1 does not perform excellently at checking the site, 2 do not perform excellently at flushing, 2 do not perform excellently at cleaning the site, and 1 reported “Other.”

Caregivers Touching the Central Line

Of 13 potential groups who could touch or access a child’s central line in the last three months, respondents reported that on average 4 different groups accessed the central line, with the most common responses being outpatient oncology clinic (98%), inpatient oncology (63%), the emergency department (49%), operating room (43%), and the home caregiver being surveyed (34%). Of the 13 respondents (12%) who reported that the patient touched or accessed the central line in the last three months, the mean patient age was 14 years, with 3 respondents reporting that their 8-year-olds touched or accessed the central line in the last three months. When asked who “primarily” cares for the child’s line, 70 respondents (67%) reported the oncology clinic, and 60 (86%) of those had totally implantable devices. Twenty-five respondents (24%) reported a parent “primarily” cares for the child’s line, 4 (4%) reported inpatient oncology, 4 (4%) reported the patient (ages 15, 17, 19 and 22), and 1 each (1%) reported a physician or grandmother.

Caregiver Beliefs About Central Line Care and Risk of Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infection

Fourteen respondents (13%) believed that it was slightly likely or not at all likely that their child will get an infection if caregivers do not perform line care practices perfectly every time (Table 1). Belief about CLABSI risk was not associated with self-report of previous central line infection (p = .98) or respondent’s educational level (p = .65).

Barriers to Best-Practice Home Central Line Care

The 27 respondents who flushed their child’s line or changed their child’s dressing cited a number of reasons why central line care can be challenging. The most common “main reason” for nonadherence with an element of the central line care bundle, cited by 7 respondents (26%), was that respondents did not believe that a specific element of the line care bundle matters. Four respondents (15%) cited “Forgot to do practices,” 3 (11%) cited “Didn’t know I was supposed to do practices,” and 2 each (7%) cited “Child is uncooperative,” “Too busy to do practices,” “Too many distractions to do practices adequately,” and “Don’t have the supplies to do practices.” Five additional respondents (19%) cited no reasons why line care can be challenging for them. No respondents cited “Don’t know how to do practices” as a reason for why line care can be challenging.

Of the 18 respondents who reported a set of practices that was most difficult to comply with, 13 reported dressing changes, 3 reported checking the site for infection, and 2 reported flushing the central line. When all 27 respondents were asked with an open-ended question what would help improve their practices, 19 cited “nothing,” while 3 asked for visual reminders and aids, 2 requested more training, and 1 each asked for dressing change kits, easier-to-access ports, or help getting their child to cooperate.

Central Line Care Training and Education Preferences

Twenty-four respondents (23%) reported they did not receive training on central line care prior to discharge for their first central line, and of those who did receive training, 33 (41%) did not perform line care practice as part of that training. Both of these responses may have been appropriate if patients were discharged with an unaccessed totally implantable device, and 31 of the 33 patients who reported not practicing as part of training, reported having a totally implantable device. Eighteen percent of respondents wished they learned more about line care, and 12% reported receiving contradictory training (Table 3, page 183). Respondents cited varied times for when they would prefer to receive line care training, although a majority (78%) preferred “hands-on” learning modalities.

Table 3.

Central Line Care Training and Education Preferences

| Characteristic | No. of Respondents (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Central Line Care Training Received | |

|

| |

| Received central line training prior to discharge for child’s first line: Yes( n = 105) | 81 (77) |

|

| |

| What kind(s) of training? (n = 81) | |

| Verbal | 79 (98) |

| Demonstration | 67 (83) |

| Written | 61 (75) |

| Practice | 48 (59) |

| Practice with feedback | 43 (53) |

| List of resources | 41 (51) |

| Other | 3 (4) |

|

| |

| If practiced, how many times did you practice? Median (IQR) (n = 47)* | |

| Totally implantable devices (n = 36) | 2 (1,4) |

| Tunneled, externalized catheters (n = 11) | 5 (2,5) |

| Peripherally inserted central catheters (n = 2)† | 2 (1,3) |

|

| |

| Something you wish you learned more about? Yes (n = 79)* | 14 (18) |

|

| |

| Are there any [line care] practices that you have received contradictory training about? (n = 105) | |

| Yes | 13 (12) |

| Flushing | 10 (10) |

| Dressing changes | 3 (3) |

| Checking the site for infection | — |

| Other | 4 (4) |

|

| |

| Central Line Care Education Preferences | |

|

| |

| Best time to receive training on line care? (n = 104)* | |

| Throughout hospital stay | 31 (30) |

| Right before discharge | 22 (21) |

| At the beginning of the hospital stay | 21 (20) |

| While at clinic | 10 (10) |

| During home care nursing | 10 (10) |

| Before admission | 6 (6) |

| Other | 4 (4) |

|

| |

| Preferred training method? (n = 105) | |

| Hands-on | 82 (78) |

| Visual (for example, video) | 11 (10) |

| Written | 7 (7) |

| Verbal | 5 (5) |

|

| |

| Preferred teacher? (n = 105) | |

| No preference | 41 (39) |

| Clinic nurse | 34 (32) |

| Inpatient nurse | 13 (12) |

| Any nurse | 10 (10) |

| Doctor | 3 (3) |

| Home health nurse | 3 (3) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

|

| |

| Who do you approach with questions about the line? (n = 105) | |

| Clinic nurse | 82 (78) |

| Doctor | 14 (13) |

| Inpatient nurse | 5 (5) |

| Other | 2 (2) |

| Home health nurse | 1 (1) |

| Any nurse | 1 (1) |

|

| |

| Who do you model your line care after? (n = 105) | |

| Clinic nurse | 76 (72) |

| Inpatient nurse | 18 (17) |

| Home health nurse | 5 (5) |

| Other | 3 (3) |

| Doctor | 2 (2) |

| Any nurse | 1 (1) |

IQR, interquartile range.

n changes, as 1 2 respondents elected to skip these questions.

Two patients had more than 1 central line.

Discussion

In a tertiary care oncology population whose inpatient service participated in a rigorous effort to reduce CLABSIs for more than two years and whose clinic participated in a rigorous effort to reduce CLABSIs for more than one year, a survey with a 95% response rate revealed concerning responses regarding home caregiver central line care practices and beliefs. Although compliance with best-practice bundles is challenging for trained health care providers,4,7,14 this study suggests that family and patient home central line care also needs continued focus from an implementation science standpoint to ensure that every child receives perfect central line care every time. Barriers for caregivers performing best-practice home central line care varied and included a lack of belief regarding the importance of some practices. It could be important to assess families and patients regarding which practices they believe are more and less important to target key items for completion in often extensive CLABSI prevention bundles. Educational preferences regarding central line care also varied, as respondents cited a number of preferences regarding when to receive line care, although the vast majority looked to clinic nurses for modeling, suggesting these nurses could be a focus of future interventions aimed at improving home central line care. Finally, of the 10 respondents who reported their minor patient cared for their own central line at some point in the last three months, 8 reported the patient cared for the line “always” or “most of the time,” including two 8-year-olds. These data further suggest that pediatric patients, and not just adult caregivers, may benefit from increased focus on line care education and best-practice implementation.

Central line maintenance care is increasingly being recognized as key to preventing pediatric CLABSIs.4,7,8,15,16 Similar to the findings of the current study, a survey of adult patient central line care also demonstrated practice variation and patient uncertainty over appropriate central line maintenance care techniques.11 As 34% of respondents in the current survey reported that they touch or access their child’s central line, and 8% reported that another adult in the household touches or accesses their child’s central line, this study suggests the need for effective educational interventions and auditing of home caregiver central line practices. Our institutional experience suggests auditing and observations of family line care is feasible, can be positively received by families, and can be associated with reduced CLABSIs,4 although it clearly needs to be augmented to achieve consistent central line care. In addition, as family caregivers can act as best-practice central line care advocates when a patient is seen at an outside institution,4,7 it is important that all caregivers, not just those who directly change dressings or flush lines, understand proper central line care maintenance procedures. Providers may want to assess caregivers’ knowledge regarding critical central line processes, even for caregivers who do not directly touch a patient’s central line or dressing. Additional family participation in quality improvement interventions may be beneficial,17 as integration of family caregivers into CLABSI prevention teams could yield new avenues for intervention and decreased CLABSI rates.

An additional avenue of research and emphasis stemming from this study is the importance of assessing the capacity of pediatric patients for central line care education and training. Children as young as 8 years of age were reported to be taking care of their own central lines, but educational materials and practice experiences have not been aimed at this age group or children and adolescents in general. Although an alternative approach could be to discourage young children from handling central lines, this could decrease patient interest in and feeling of control over their medical course.18 In data not shown, some adolescents qualitatively reported risky central line care behaviors, an expected finding, although one not often asked about by clinic staff. Patients could benefit from clear clinic protocols that ask caregivers who takes care of the child’s central line and the creation of targeted educational and auditing materials toward many pediatric age groups. Furthermore, a discussion among clinicians, adult caregivers, and children about when a child is ready to care for his or her central line, both physically and mentally,18 could contribute to reduced infection risk without removing childhood autonomy. Finally, involving child life practitioners, who specialize in explaining complex medical topics to children, could improve central line care education for children without scaring already vulnerable patients.

Involving families and pediatric patients in central line care is likely integral to reducing ambulatory CLABSIs. Engaging pediatric patients in this type of care is challenging, given the triadic nature of communication,19 but models exist to suggest how it can be accomplished.20–22 Barriers to this engagement and family best-practice care included respondents not believing that a specific element of the line care bundle matters, forgetting to do practices, and not knowing that they were supposed to do practices. Dressing changes were the most commonly cited “difficult to comply with” practice. Although it is easier to understand why a dressing change is perceived as more challenging than the simpler and quicker line flush, understanding why families do not believe certain practices are important is more difficult. Reasons for these beliefs may derive from parents’ witnessing varied line care practices by different clinicians and the challenge inherent in linking a specific practice to an infection that may occur days or even weeks later. Our own clinic has been trying to implement all the suggestions from these data in the busy oncology clinic setting. Standardizing central line care across all the inpatient, ambulatory, and home spheres should help overcome many barriers to family central line care. This research draws attention to the importance of engaging children in their own care in both the acute and subacute settings.

A limitation of this study is its single-center nature, which could reduce its generalizability. Although our clinic and oncology population are unique, discussions with other oncology groups at national conferences suggest the issues presented are likely occurring at many similar sites. Further research is needed to determine the generalizability of these findings. Social desirability bias is also a concern in this study. One would expect that caregivers would report performing central line care practices correctly more often than they actually do them, suggesting that actual caregiver practices may be worse than the data reported here. Studies involving direct observation of parents in home settings would improve our ability to understand this potential bias. In addition, many respondents in this survey were not the primary person to provide central line care for their child. It is still important to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of all family members because prior studies suggest that family empowerment can influence the central line care of health care practitioners4,7 and therefore reduce CLABSI. Finally, this study has a potential for recall bias, as respondents were asked to remember who accessed their child’s central line in the last three months, which reasons they “or another caregiver” flush or change the central line dressing, and how they were trained on central line care. It is unclear how recall bias affected our study, but future work could include central line patient registries, which could detail which modalities were used to teach certain patient groups, record direct observation of line care techniques, and report exact central line access patterns.

Conclusion

This survey of caregiver practices and perceptions of home-based pediatric oncology central line care identified appreciable discrepancies between recommended best practices and self-reported central line care at home. Future interventions aimed at reducing ambulatory pediatric oncology CLABSIs should target appropriate educational experiences and assessments for adult caregivers and patients and identify ways to improve compliance with best-practice care, particularly among pediatric patients themselves.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Rinke was supported by Grant Number K08HS021282 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Rinke was also supported by Grant Number 5KL2RR025006 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health and the Roadmap for Medical Research. Drs Miller and Bundy were supported by the Children’s Hospital Association for their work.

Appendix 1. Oncology Family Survey Form

References

- 1.Goudie A, et al. Attributable cost and length of stay for central line–associated bloodstream infections. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1525–1532. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudeck MA, et al. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Report, data summary for 2010, device-associated module. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(10):798–816. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downes KJ, et al. Polymicrobial bloodstream infections among children and adolescents with central venous catheters evaluated in ambulatory care. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Feb 1;46(3):387–394. doi: 10.1086/525265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinke ML, et al. Central line maintenance bundles and CLABSIs in ambulatory oncology patients. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1403–1412. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinke ML, et al. Ambulatory pediatric oncology CLABSIs: Epidemiology and risk factors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(11):1882–1889. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Grady NP, et al. Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(4 Suppl 1):S1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rinke ML, et al. Implementation of a central line maintenance care bundle in hospitalized pediatric oncology patients. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):e996–1004. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bundy DG, et al. Children’s Hospital Association Hematology/Oncology CLABSI Collaborative. Preventing CLABSIs among pediatric hematology/oncology inpatients: National collaborative results. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1678–1685. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinke ML, et al. Bringing central line-associated bloodstream infection prevention home: CLABSI definitions and prevention policies in home health care agencies. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(8):361–370. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(13)39050-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Møller T, et al. Patient education—A strategy for prevention of infections caused by permanent central venous catheters in patients with haematological malignancies: A randomized clinical trial. J Hosp Infect. 2005;61(4):330–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weingart SN, et al. Standardizing central venous catheter care by using observations from patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(3):321–326. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.321-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klassen AF, et al. Parents of children with cancer: Which factors explain differences in health-related quality of life. Int J Cancer. 2011 Sep 1;129(5):1190–1198. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flodgren G, et al. Interventions to improve professional adherence to guidelines for prevention of device-related infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Mar 28;3:CD006559. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006559.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson MZ, et al. Reduction of central line-asssociated bloodstream infections in a pediatric hematology/oncology population. Am J Med Qual. 2014;29(6):484–490. doi: 10.1177/1062860613509401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller MR, et al. Decreasing PICU catheter-associated bloodstream infections: NACHRI’s quality transformation efforts. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):206–213. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurer M, et al. Guide to Patient and Family Engagement: Environmental Scan Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. [Accessed Mar 3, 2015]. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/finalreports/ptfamilyscan/ptfamilyscan.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuther TL. Medical decision-making and minors: Issues of consent and assent. Adolescence. 2003;38(150):343–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cahill P, Papageorgiou A. Triadic communication in the primary care paediatric consultation: A review of the literature. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(544):904–911. doi: 10.3399/096016407782317892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han E, et al. Survey shows that fewer than a third of patient-centered medical home practices engage patients in quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):368–375. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landers T, et al. Patient-centered hand hygiene: The next step in infection prevention. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(4 Suppl 1):S11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert V, Glacken M, McCarron M. Using a range of methods to access children’s voices. J Res Nurs. 2013;18(7):601–616. [Google Scholar]