Abstract

Endothelial cells play a major role in the initiation and perpetuation of the inflammatory process in health and disease, including their pivotal role in leukocyte recruitment. The role of pro-inflammatory transcription factors in this process has been well-described, including NF-κB. However, much less is known regarding transcription factors that play an anti-inflammatory role in endothelial cells. Myocyte enhancer factor 2 C (MEF2C) is a transcription factor known to regulate angiogenesis in endothelial cells. Here, we report that MEF2C plays a critical function as an inhibitor of endothelial cell inflammation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibited MEF2C expression in endothelial cells. Knockdown of MEF2C in endothelial cells resulted in the upregulation of pro-inflammatory molecules and stimulated leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. MEF2C knockdown also resulted in NF-κB activation in endothelial cells. Conversely, MEF2C overexpression by adenovirus significantly repressed TNF-α induction of pro-inflammatory molecules, activation of NF-κB, and leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. This inhibition of leukocyte adhesion by MEF2C was partially mediated by induction of KLF2. In mice, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced leukocyte adhesion to the retinal vasculature was significantly increased by endothelial cell-specific ablation of MEF2C. Taken together, these results demonstrate that MEF2C is a novel negative regulator of inflammation in endothelial cells and may represent a therapeutic target for vascular inflammation.

Endothelial cells (ECs) play a major role in promoting the inflammatory response, including the recruitment of circulating leukocytes to the vessel wall and surrounding tissue at sites of inflammation (Cook-Mills and Deem, 2005; Pober and Sessa, 2007; Rao et al., 2007; Granger and Senchenkova, 2010; Kvietys and Granger, 2012). The adoption of a pro-inflammatory phenotype is a critical function of endothelial cells during the body’s protective response to harmful stimuli. Conversely, endothelial cell dysfunction characterized by inappropriate and excessive endothelial activation contributes to diverse diseases including sepsis, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and cancer. Drugs targeting endothelial responses to inflammation therefore have great clinical implications, highlighting the need to better understand how inflammation is regulated in endothelial cells (Pober and Sessa, 2007).

Endothelial activation leading to recruitment of leukocytes involves stimulation of ECs by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α (Pober and Sessa, 2007). Stimulated endothelial cells upregulate levels of cell surface adhesion molecules including E-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), which mediate rolling and attachment of leukocytes to the vascular wall (Rao et al., 2007). NF-κB is a major pro-inflammatory transcription factor activated in ECs by inflammatory cytokines (Oeckinghaus and Ghosh, 2009) and plays a central role in upregulating the expression of adhesion molecules and other pro-inflammatory genes (Collins et al., 1995; Blackwell and Christman, 1997; Zhou et al., 2007). There is much less known regarding transcription factors that play an anti-inflammatory role in endothelial cells.

The myocyte enhancer factor (MEF2) family of transcription factors plays a critical role in diverse developmental programs (Shore and Sharrocks, 1995; Potthoff and Olson, 2007). In adult tissues, MEF2 proteins are important regulators of cellular stress response and remodeling and have been implicated in cell survival, apoptosis, and proliferation (Potthoff and Olson, 2007). Of the MEF2 transcription factors, MEF2C plays a critical role in vascular cells (Potthoff and Olson, 2007); targeted deletion of mef2c in mice leads to severe vascular defects (Lin et al., 1997, 1998; Bi et al., 1999). MEF2C is involved in regulating endothelial integrity and survival (Potthoff and Olson, 2007). Our lab and others have demonstrated that MEF2C modulates VEGF regulation of endothelial cells, including gene expression changes (Maiti et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2011). We recently reported that MEF2C regulates endothelial cell angiogenesis; mice with endothelial-cell specific ablation of MEF2C exhibited marked increase in vascular regrowth under stress conditions (Xu et al., 2012). Knockdown of MEF2C in endothelial cells regulated endothelial cell survival and tube formation, further confirming the role of this transcription factor in the regulation of angiogenesis (Xu et al., 2012). Consistent with this, MEF2C was recently reported as a negative regulator of angiogenic sprouting of endothelial cells (Sturtzel et al., 2014).

The objective of the present study was to investigate whether MEF2C regulates endothelial cell inflammation, with particular focus on leukocyte adhesion. We found that knockdown of MEF2C increases endothelial cell adhesion to leukocytes, with increased NF-κB activity and expression of pro-inflammatory molecules. Conversely, adenovirus-mediated MEF2C overexpression strongly suppressed TNF-α-induced leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells by inhibiting NF-κB activation and TNF-α-induced pro-inflammatory gene expression, at least in part via induction of Krueppel-like factor 2 (KLF2). Endothelial cell-specific MEF2C conditional knockout mice exhibited significantly higher leukocyte adhesion to the retinal vasculature after LPS stimulation, as compared to wild-type mice. Our results indicate that MEF2C represents an important negative regulator of endothelial inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Human retinal endothelial cells (HRECs; Cell Systems, Kirkland, WA) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were cultured in EGM2-MV medium (Lonza) in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C, and medium was changed every 2–3 days. HRECs were grown in fibronectin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) coated dishes and were used at passages 6–10. For TNF-α treatment, cells were cultured in EGM2 without fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen) overnight and treated with TNF-α (Promega, Madison, WI) for 6 h. The human promyelocytic cell line HL-60 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection, and was cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS.

siRNA transfection

To inhibit MEF2C or KLF2 expression, HRECs and HUVECs were transfected with 25 nM of negative control siRNA (AM4611, Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA), MEF2C siRNA (#1: 106791, #2: 143535, Applied Biosystems) and KLF2 siRNA (s20271, Applied Biosystems) using siPORT Amine transfection reagent (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Knockdown efficiency was verified by real-time PCR and western blot analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from cells was isolated using TRIZOL (Invitrogen) or RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Single-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using an oligo (dT) 18-mer as primer and the MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) in a final reaction volume of 25 μl. Real-time PCR was performed with the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) and run on StepOnePlus Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystem). The primers were: MEF2C sense (5′AGTGGGTGGGAAAGGGTCATTACA-3′) and antisense (5′-TAGCCAAGGCTTCTGCTGGTACTT-3′); PLAU sense (5′-TCACCACCAAAATGCTGTGT-3′) and antisense (5′-CCAGCTCACAATTCCAGTCA-3′); HO-1 sense 5′-AACTTTCAGAAGGGCCAGGT-3′) and antisense (5′-GTAGACAGGGGCGAAGACTG-3′); VCAM1 sense (5′-AAAAGCGGAGACAGGAGACA-3′) and antisense (5′-AGCACGAGAAGCTCAGGAGA-3′); MCP1 sense (5′-CCCCAGTCACCTGCTGTTAT-3′) and antisense (5′-AGATCTCCTTGGCCACAATG-3′); E-selectin sense (5′-GCCTAAACCTTTGGGTGAAA-3′) and antisense (5′-CATAGCTTCCGTGGAGGTGT-3′); ICAM-1 sense (5′-CGCTGAGCTCCTCTGCTACT -3′) and antisense (5′-GATGACTTTTGAGGGGGACA -3′); IL-8 sense (5′-TAGCAAAATTGAGGCCAAGG-3′) and antisense (5′-AAACCAAGGCACAGTGGAAC-3′); KLF2 sense (5′-CACCAAGAGTTCGCATCTGA-3′) and antisense (5′-CGTGTGCTTTCGGTAGTGG-3′); GAPDH sense (5′-TCGACAGTCAGCCGCATCTTCTTT-3′) and antisense (5′-ACCAAATCCGTTGACTCCGACCTT-3′); β-actin sense (5′-AATGTGGCCGAGGACTTTGATTGC-3′) and antisense (5′-AGGATGGCAAGGGACTTCCTGTAA-3′). GAPDH or β-actin was used for normalization.

Western blot analysis

Cells after indicated treatments were washed with PBS and lysed in Laemmli sample buffer (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The protein samples from total cell lysates were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). After incubating with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies, the blots were detected with the Supersignal West Pico or Femto Chemiluminescent Substrates (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). For reprobing, the blots were washed in Western blot stripping buffer (Thermo Scientific) for 10 min before proceeding with new blotting. Rabbit monoclonal MEF2C antibody (1:1000), ICAM1 antibody (1:1000), monoclonal phosphos-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) antibody (1:1000) and rabbit monoclonal NF-κB p65 antibody (1:1000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). VCAM1 antibody (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA) was used at 1:1000 dilution. PLAU antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). HO-1 antibody was ordered from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). Anti-KLF2 antibody was kindly provided by Dr. Huck-Hui Ng (National University of Singapore). Monoclonal GAPDH antibody (1:2000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or lamin B antibody (1:400) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used for loading control normalization. Leukocyte adhesion assay

The leukocyte adhesion assay was performed as previously described (Harris et al., 2008). HL-60 cells were labeled with calcein AM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h and incubated with HREC for 30 min. The cells in culture plates were washed with serum-free EBM2 medium for 2–3 times to remove non-adherent cells. 6–8 random images per well were taken under 20 × objective with Zeiss Fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) and fluorescent HL-60 cells were counted using NIH Image J program (Schneider et al., 2012).

Nuclear extract preparation and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts from HREC were prepared using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (ThermoFisher Scientific) following the manufacturers’ instructions. Proteins were quantified by the BCA protein assay (BioRad) and protein extracts were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. NF-κB gel shift oligonucleotides (SC-2505: 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′ and mutant oligonucleotides (SC-2511: 5′-AGTTGAGGCGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. DNA probes were labeled with [γ-32P] ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Inc. lpswich, MA) and purified by on a Sephadex G-50 column (GE Healthcare). The reaction contained 2 μl of 5 × mobility shift buffer (125 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 300 mM KCl2, 5 mM DTT, 5 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol), poly-(dIdC) 0.1 μg/μl, (γ-32P)-ATP-labelled probe 1 μl and 7 μg of nuclear extracts in a total volume of 10 μl. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved by electrophoresis at 4°C on 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels in 0.5 × TBE. Gels were dried and detected by autoradiography.

Adenovirus preparation and infection

Replication-deficient adenovirus expressing mouse full-length MEF2C (Ad-MEF2C) and green fluorescent protein (GFP, Ad-GFP) were kindly provided by Dr. Jeffery Molkentin (Xu et al., 2006). HRECs were seeded in 12-well plate or 10 cm dish and were 75% confluent by the next day. Cells were incubated with Ad-GFP and Ad-MEF2C at 300 infection unit (IFU) per cell for 48 h. Before TNF-α treatment, cells were washed with PBS, and cultured in EGM2 without FBS overnight.

Immunofluorescence staining of NF-κB in HRECs

HRECs attached onto the fibonectin-coated coverglass were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, and washed with PBS for three times. After permeabilization in 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min, cells were washed with PBS for three times. Cells were then blocked in 4% BSA with PBS plus 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST), and incubated with anti-NF-κB p65 antibody (Cell signaling, 1:50) overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed with PBST and then were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa flour 594 (Invitrogen). DAPI (Vector labs) was used to stain nuclei. Photographs were taken with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

Mice and treatment

Endothelial cell-specific mef2c conditional knockout mice Tie2-cre+/mef2clox/Δ2 (referred to as mef2cΔEC) were generated as described (Xu et al., 2012). Littermate mice mef2c+/loxp were used as wild-type control mice. Adult (6–8 week old) mef2cΔEC and wild-type control mice were subjected to a model of acute retinal vascular inflammation (Al-Shabrawey et al., 2008; Nagai et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009) by a single intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 1mg/kg in PBS, from Escherichi coli, Sigma). Age-matched control mice received vehicle (PBS). Mice were killed 24 h later for leukocyte adhesion analysis. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and conducted in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals and in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Analysis of leukocyte adhesion in vivo

The adhesion of leukocytes to retinal vascular wall was analyzed by perfusing fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated concanavalin A lectin (ConA, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), in similar fashion to previous studies (Al-Shabrawey et al., 2008; Nagai et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). Under deep anesthesia, the chest cavity was carefully opened, and a 24-gauge perfusion cannula was inserted into the left ventricle. 15 ml PBS was perfused to wash out all nonadherent blood cells. To label adherent leukocytes, 15 ml ConA (40 μg/ml in PBS) was perfused followed by injection with PBS to remove residual ConA. The eyeballs were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The retinas were then dissected and observed at 20 × objective under fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy). The total number of adherent leukocytes per retina was counted in a masked fashion.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SD. The Student t-test and Wilcoxon rank test were used to perform statistical analysis. A value of P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

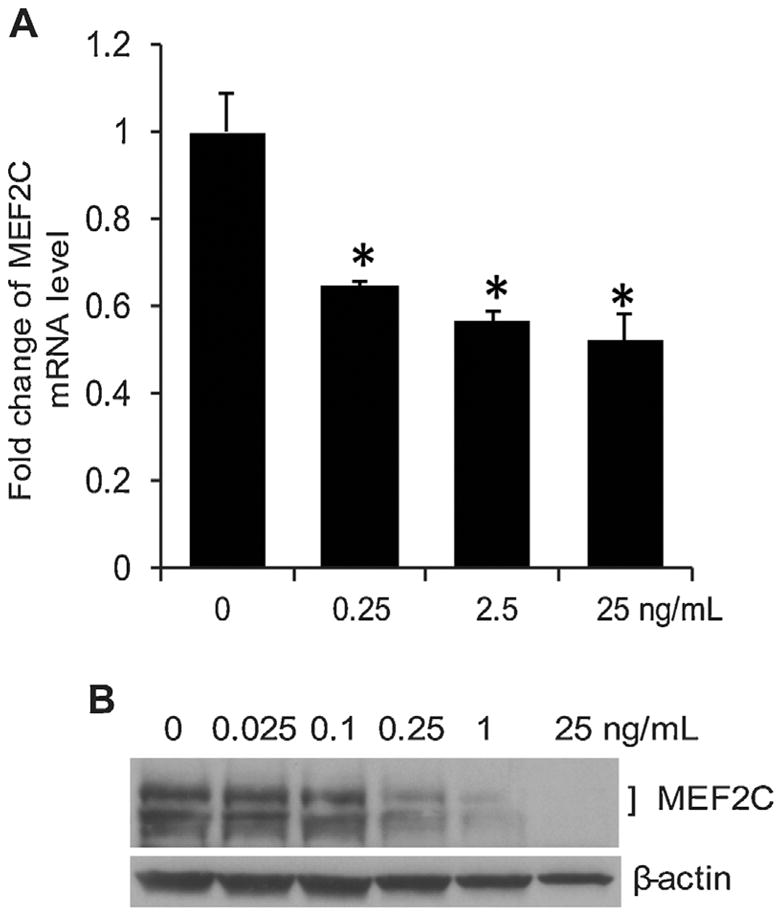

TNF-α inhibits MEF2C expression in endothelial cells

We previously demonstrated that the expression of MEF2C is up-regulated in endothelial cells by VEGF (Maiti et al., 2008). We were interested in determining whether the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α has any effect on the expression of MEF2C. After 8 h treatment of TNF-α at different doses from 0.25 ng/ml to 25 ng/ml, the mRNA level of MEF2C in endothelial cells was significantly decreased (Fig. 1A). The protein level of MEF2C was not appreciably affected by lower doses of TNF-α (0.025 and 0.1 ng/ml), but was dramatically downregulated by higher doses of TNF-α ranging from 0.25 to 25 ng/ml (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

TNF-α inhibits MEF2C expression at mRNA level (A) and protein level (B) in human endothelial cells. (A) Human retinal endothelial cells (HRECs) were treated with different doses of TNF-α for 8 h. Total RNA was isolated and reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg total RNA. Quantitative real-time PCR was used to detect the expression of MEF2C mRNA. *, P<0.05 compared with PBS-treated cells. (B) Western blot analysis of MEF2C protein in HRECs treated with different doses of TNF-α for 24 h. Total cell lysates were analyzed for the presence of MEF2C protein. The same membrane was blotted with anti-β-actin antibody for normalization. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

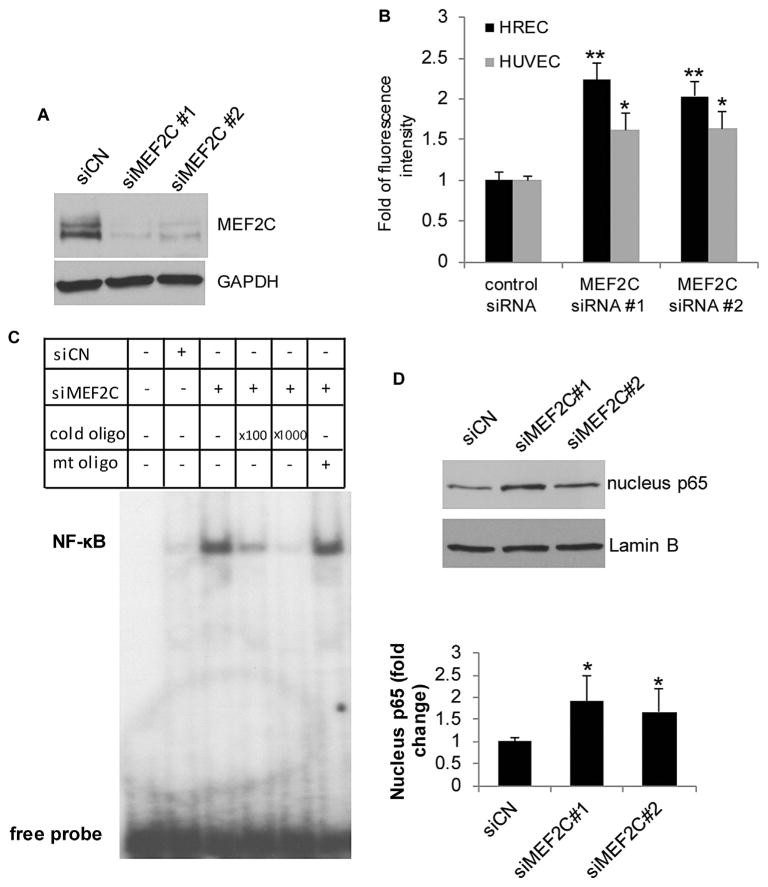

Knockdown of MEF2C increases leukocyte adhesion to human retinal and umbilical vein endothelial cells and NF-κB binding activity

The strong downregulation of MEF2C expression by TNF-α raised the question of whether MEF2C has any effect in regulating endothelial cell inflammation. We looked at whether endothelial MEF2C regulates leukocyte adhesion, since leukocyte recruitment is a critical function of endothelial cells during inflammation (Cook-Mills and Deem, 2005; Rao et al., 2007). We first determined whether knockdown of MEF2C in endothelial cells affects adhesion to leukocytes. We employed two separate siRNAs targeting MEF2C, and confirmed that both siRNAs significantly down-regulated the expression of MEF2C in endothelial cells (Fig. 2A). Transfection of human retinal endothelial cells with either MEF2C siRNA significantly increased leukocyte adherence, as compared to control siRNA (Fig. 2B). The quantified fluorescence intensity from calcein AM-labeled leukocytes was increased around two-fold in MEF2C siRNAs-transfected HRECs compared to control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2B). We also found the same effect in HUVECs, with MEF2C knockdown leading to significant increase in leukocyte adhesion (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Knockdown of MEF2C in endothelial cells increases leukocyte adhesion and the activity of NF-κB. HRECs were transfected with control siRNA and MEF2C siRNAs for 48 h. (A) Western blot analysis of MEF2C protein in MEF2C siRNA-transfected HRECs. (B) Leukocyte adhesion to HRECs and HUVECs were significantly increased after MEF2C siRNA transfection. *, P< 0.01 and **, P<0.001 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. (C) EMSA of NF-κB in MEF2C siRNA-transfected cells. Knocking down MEF2C increased nuclear binding activity of NF-κB. Nuclear extracts from control siRNA and MEF2C siRNA- transfected cells were prepared and incubated with [γ-32P] ATP labelled-NF-κB concensus and mutant oligonucleotides. 100 fold and 1000 fold excess of NF-κB wild-type probe or mutant (mt) probes were included where indicated to demonstrate specificity of binding. (D) Western blot analysis of NF-κB p65 in the nuclear extract of siRNA-transfected cells. *, P<0.05 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

The transcription factor NF-κB is known to be a pivotal mediator of the inflammatory response in endothelial cells (Pober and Sessa, 2007). Since MEF2C knockdown in endothelial cells promoted an inflammatory phenotype reflected by increased leukocyte adherence, we further investigated whether NF-κB activity was also affected in endothelial cells. Western blot analysis using nuclear extract from MEF2C siRNA-transfected HRECs showed increased nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 compared to control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2D). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) also showed that MEF2C knockdown also significantly enhanced DNA binding of NF-κB p65 in HRECs (Fig. 2C), consistent with the increase in nuclear translocation of p65.

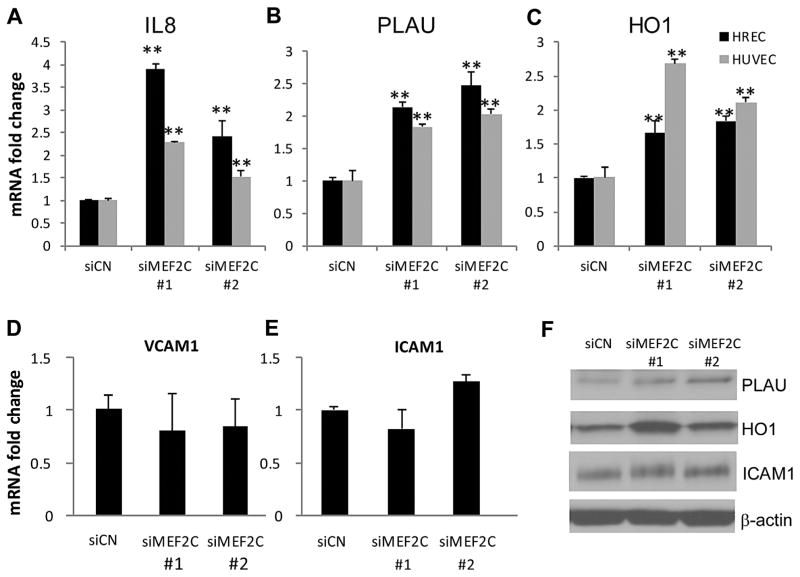

We also examined the effect of MEF2C knockdown on expression of pro-inflammatory genes and acute phase proteins. We specifically looked at genes known to be regulated by NF-κB, namely interleukin-8 (IL-8) (Hoffmann et al., 2002), urokinase-type plasminogen activator (PLAU) (Wang et al., 2000), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (Alam and Cook, 2007; Rushworth et al., 2011). As shown in Figure 3A–C, IL-8, PLAU, and HO-1 were all significantly upregulated by MEF2C knockdown in both HRECs and HUVECs. Western blot analysis also demonstrated upregulation of PLAU and HO-1 protein after MEF2C knockdown (Fig. 3F). However, some key genes playing important roles in the binding of endothelial cells to leukocytes, such as VCAM1 and ICAM1, were not affected by the knockdown of MEF2C at the RNA level 24 h after siRNA transfection (Fig. 3D and E). No change in ICAM1 protein level was found in cells subjected to MEF2C knockdown (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Effect of MEF2C knockdown on pro-inflammatory and adhesion molecule expression in endothelial cells. (A–E) HRECs (black bars) and HUVECs (gray bars) were transfected with control siRNA and two different MEF2C siRNAs for 24 h. Quantitative real-time PCR was used to detect the expression of MEF2C and several pro-inflammatory genes. (F) Western blot analysis of pro-inflammatory genes at 48 hours after siRNA transfection. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

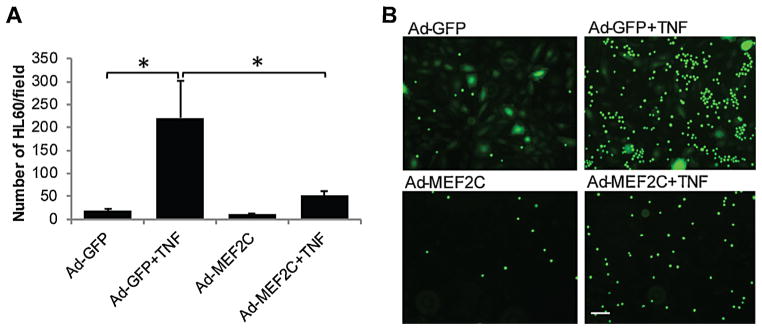

Overexpression of MEF2C inhibits TNF-α-induced leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells and expression of pro-inflammatory genes

Our MEF2C knockdown studies demonstrated that inhibition of MEF2C increases the inflammatory phenotype in endothelial cells, including leukocyte adhesion. We were therefore interested in examining the effect of MEF2C overexpression in endothelial cells. We first looked at TNF-α-induced leukocyte adhesion following adenovirus-mediated overexpression of MEF2C. Ad-MEF2C-transduction of endothelial cells successfully resulted in overexpression of MEF2C at the protein level (Supplemental Figure 1 A). TNF-α treatment strongly increased leukocyte binding to control (Ad-GFP-transduced) endothelial cells, as expected (Fig. 4A and 4B). In contrast, overexpression of MEF2C in HRECs significantly suppressed this TNF-α-induced leukocyte adhesion by 76.6% (Fig. 4A and B).

Fig. 4.

MEF2C overexpression inhibits TNF-α-induced leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. (A) HRECs were pre-infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-MEF2C, followed by treatment with TNF-α for 6 h. The number of leukocytes adhering to HRECs was counted in eight randomly-selected fields (10× objective). *, P<0.05. (B) Representative images of leukocyte adhesion to HRECs. Scale bar: 50 μm. Data are representative of four separate experiments.

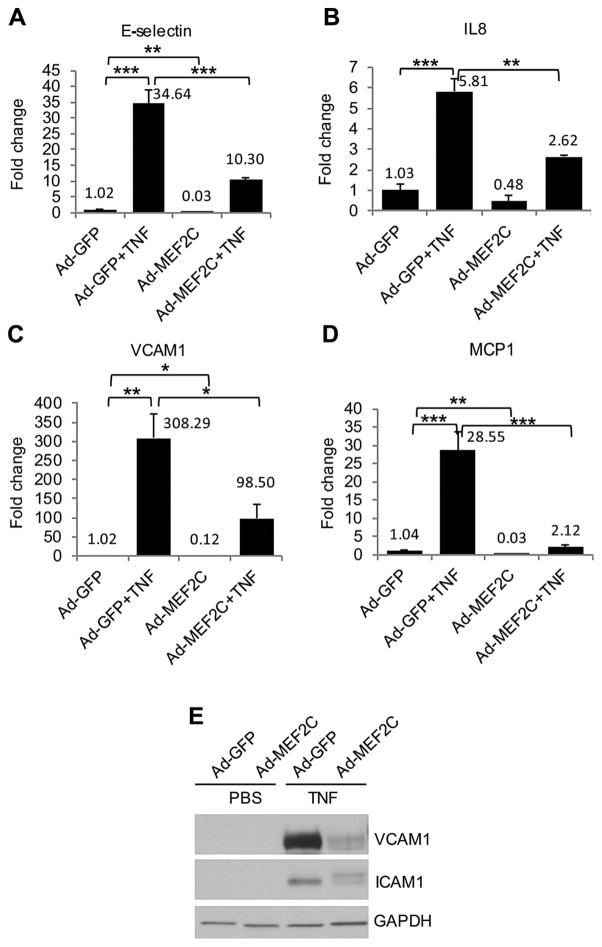

Overexpression of MEF2C inhibits TNF-α-induced pro-inflammatory gene expression

In light of the dramatic effect of endothelial MEF2C overexpression on leukocyte adhesion, we investigated whether this might occur via modulation of adhesion molecules and pro-inflammatory genes. We therefore measured the mRNA levels of IL-8, E-selectin, VCAM1 and MCP1 by q-PCR. TNF-α significantly increased the expression of IL-8, E-selectin, VCAM1 and MCP1 in Ad-GFP-infected HRECs. Transduction of HRECs with Ad-MEF2C significantly reduced the expression of E-selectin and VCAM1 by about 70% compared to TNF-α-treated control (Ad-GFP-transduced) cells. The expression of IL-8 and MCP1 were reduced by 55% and 92% respectively in Ad-MEF2C-infected cells, compared to Ad-GFP-infected cells (Fig. 5A–D). We also looked at protein levels of the adhesion molecules VCAM1 and ICAM1. These were expressed very low levels in HRECs in the basal state, and significantly upregulated by TNF-α (Fig. 5E). Ad-MEF2C transduction significantly suppressed TNF-α induction of VCAM1 and ICAM1 protein in HRECs (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

MEF2C overexpression inhibits TNF-α-induced proinflammatory molecules expression. 48 h after infection with Ad-GFP and Ad-MEF2C, HRECs were treated with TNF-α for 6 h. Quantitative real-time PCR (A–D) and Western blot were used to detect the expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules (E). *, P<0.05, **, P<0.01, and ***, P< 0.001. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

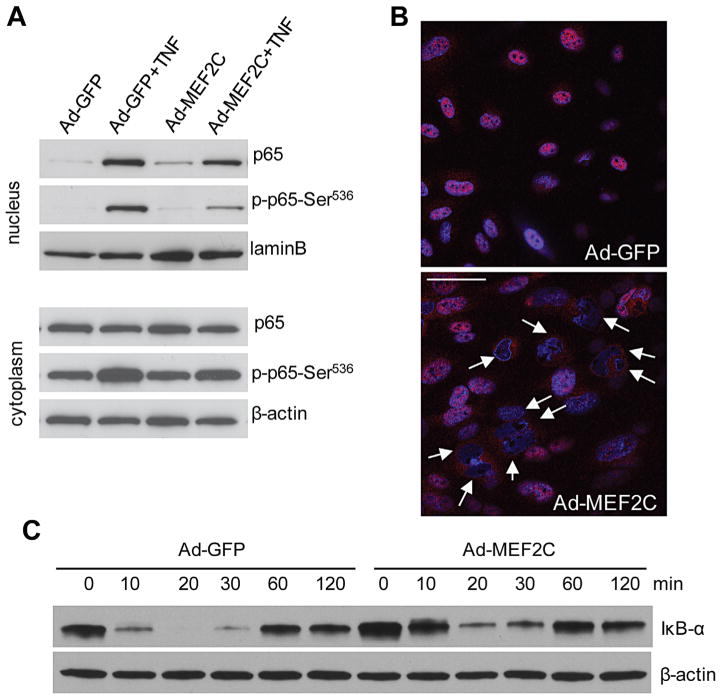

Overexpression of MEF2C in endothelial cells inhibits TNF-α-induced NF-κB translocation

The transcription factor NF-κB is active by TNF-α and serves as a major mediator of the pro-inflammatory effect of TNF-α, including its induction of various pro-inflammatory genes. We therefore speculated that overexpression of MEF2C might affect the activity of NF-κB. Western blot analysis using nuclear extracts clearly showed increased NF-κB p65 translocation into nucleus after TNF-α treatment. However, TNF-α-induced p65 nuclear translocation was significantly inhibited in Ad-MEF2C-transduced endothelial cells, as compared with Ad-GFP-transduced cells (Fig. 6A). Immunostaining of p65 confirmed that overexpression of MEF2C suppressed TNF-α-induced p65 nuclear translocation (Fig. 6B). Since the phosphorylation of Ser536 affects the transactivation ability of p65, we also investigated whether MEF2C affects the phosphorylation of p65 at Ser536. As shown in Figure 6A, overexpression of MEF2C significantly inhibited TNF-α-induced Ser536 phosphorylation.

Fig. 6.

MEF2C overexpression inhibits TNF-α-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation and its phosphorylation. (A) HRECs infected with Ad-GFP and Ad-MEF2C were treated with TNF-α for 30 min. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were analyzed by Western blot using anti-phospho p65 (Ser536) and anti-total p65 antibodies. (B) Nuclear localization of NF-κB p65 was suppressed after MEF2C overexpression. Arrows indicate cells lacking p65 in the nucleus. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA and analyzed by immunofluorescence with anti-NF-κB p65 (red) and DAPI for nuclei staining (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Western blot analysis of IκB-α expression in Ad-MEF2C and Ad-GFP- infected HRECs after treated with TNF-α for indicated durations. All experiments were performed at least twice independently.

IκB is an important regulator of NF-κB and binds to NF-κB in quiescent cells, thereby preventing it from entering nucleus to activate gene expression. IκB is phosphorylated upon TNF-α stimulation and degraded, thereby releasing NF-κB and enabling its nuclear translocation. We therefore asked whether MEF2C overexpression can modulate IκB in endothelial cells. As shown in Fig. 6C, IκB was quickly degraded in control cells, 10 min after TNF-α treatment. A similar degree of IκB degradation was observed 20 min after TNF-α treatment in cells with MEF2C overexpression. MEF2C overexpression therefore delayed IκB degradation, which may underlie the associated increase in NF-κB activity.

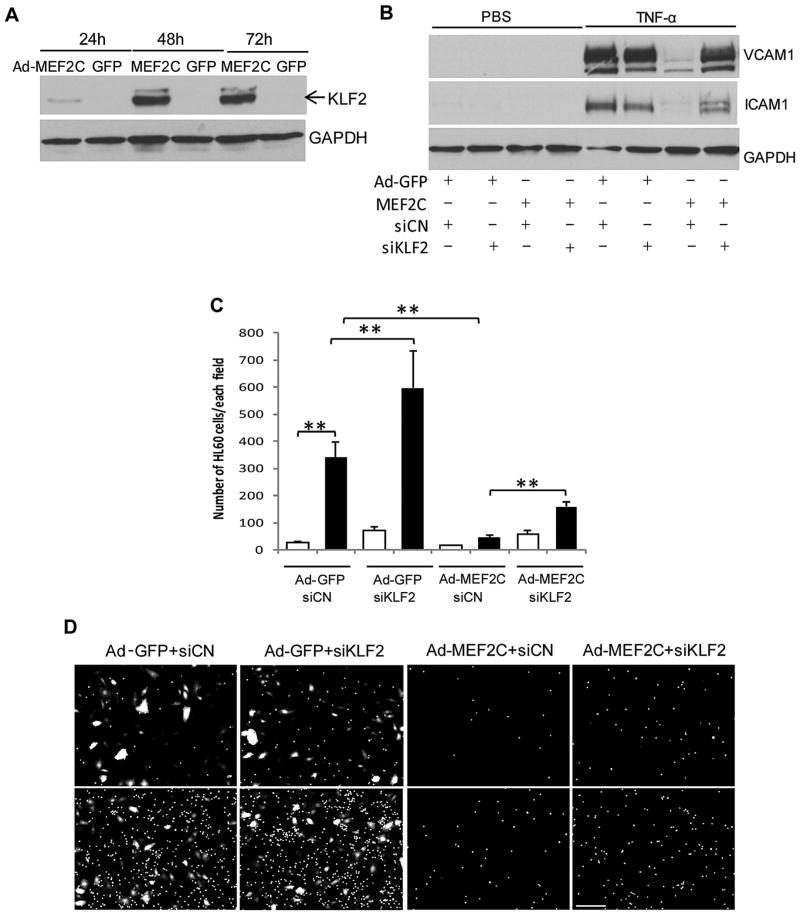

Inhibition of leukocyte adhesion by MEF2C is partially mediated by activation of KLF2 expression

KLF2 is an important anti-inflammatory transcription factor in endothelial cells (Rao et al., 2007), and its expression can be regulated by MEF2. We therefore considered KLF2 as a possible mediator of the anti-inflammatory effects of MEF2C. We found that MEF2C overexpression significantly increased KLF2 expression in endothelial cells (Fig. 7A). In order to determine whether KLF2 plays a role in mediating MEF2C inhibition of leukocyte adhesion, we used siRNA to knockdown KLF2 in MEF2C-overexpressing endothelial cells. The expression of KLF2 was effectively down-regulated by its siRNA as early as 24 h after siRNA transfection (supplemental Figure 1B). The downregulation of multiple pro-inflammatory genes by MEF2C overexpression, notably MCP1, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin (but not IL-8) was partially counteracted by KLF2 knockdown (Fig. 7B and Supplemental Figure 1B).

Fig. 7.

Knockdown of KLF2 rescues the inhibition of TNF-α-induced proinflammatory gene expression and leukocyte adhesion by MEF2C over-expression. (A) Western blot analysis of KLF2 after MEF2C over-expression. (B) 24 h after the infection of Ad-GFP and Ad-MEF2C, HRECs were transfected with siCN or siKLF2. Cells then were treated with TNF-α (black bar) or PBS (white bar) for 6 h. Total cell lysates were analyzed for the presence of VCAM1 and ICAM1 protein. (C) HRECs were pre-infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-MEF2C, followed by siRNA transfection for 48 h and treatment of 0.1 ng/mL TNF-α (black bar) or PBS (white bar) for 6 h. The numbers of leukocytes adherent to HRECs was counted in five randomly-selected fields (10× objective). **, P<0.01. (D) Representative images of HL-60 cell adhesion to HRECs. Scale bar: 50 μm. Data are representative of three separate experiments.

Consistent with its effects on inflammatory gene expression, KLF2 knockdown in endothelial cells also modulated leukocyte adhesion. The number of leukocytes adherent to siKLF2 transfected-endothelial cells was significantly higher than in control siRNA-transfected cells under both basal conditions and following TNF-α treatment (Fig. 7C and D). However, knockdown of KLF2 only partially attenuated the inhibitory effect of MEF2C overexpression on TNF-α-induced HL60 cell adhesion to HRECs.

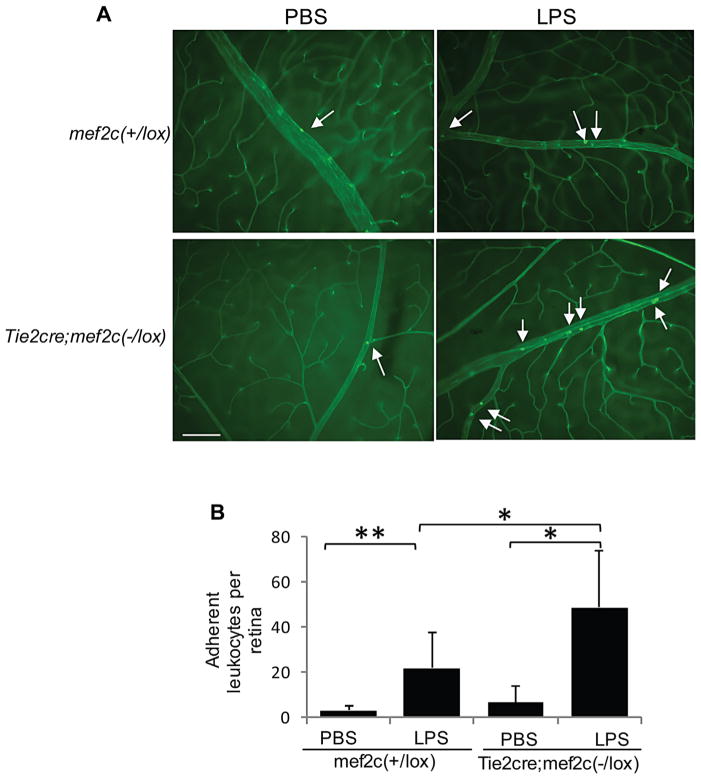

Endothelial cell-specific deletion of MEF2C in mice increases LPS-induced leukocyte adhesion to retinal vasculature

Leukocyte adhesion to the vascular wall is a hallmark of retinal vascular inflammation, serving as a critical step in leukocyte infiltration. Our in vitro studies strongly indicate that MEF2C regulates vascular endothelial cells with respect to leukocyte adhesion, playing an anti-inflammatory role. We investigated whether endothelial MEF2C regulates leukocyte adhesion in vivo during inflammation. For this purpose, we employed an endothelial cell specific-MEF2C conditional knockout mouse (Xu et al., 2012), which allows us to directly examine the role of MEF2C in this cell type in vivo. We used a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced retinal inflammation model (Al-Shabrawey et al., 2008; Nagai et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009), a system which allows easy assessment and visualization of leukocyte adhesion in vivo. As shown in Figure 8A, there were very few leukocytes adherent to the retinal vascular wall under normal conditions in both mef2cΔEC mice and wild-type control mice. LPS injection treatment increased the number of adherent leukocytes in both wild-type mice and mef2cΔEC mice. The number of adherent leukocytes was over two-fold higher in the endothelial cell-specific mef2c conditional knockout mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Deletion of mef2c in endothelial cells increases LPS-induced leukocyte adhesion to the retinal vasculature. (A) FITC-conjugated Con A staining of adherent leukocytes in the retinal vasculature of endothelial cell specific-mef2c conditional knockout mice and corresponding wild-type control mice. Leukostasis was analyzed 24 h after mice received intraperitoneal injection of LPS (1 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle (PBS). Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Quantification of adherent leukocytes in retinal vasculature of mef2c knockout mice (n =5 for PBS, n =7 for LPS) and wild-type mice (n =9 for PBS, n =14 for LPS). *, P<0.05, **, P<0.01.

Discussion

Endothelial cells play a critical role in the inflammatory response, altering their phenotype to support diverse aspects of this process, including the recruitment of leukocytes (Pober and Sessa, 2007; Rao et al., 2007). Although endothelial cell activation constitutes an appropriate and important part of the body’s response to infection and acute tissue injury, unchecked EC activation is now widely recognized to contribute to multiple disease processes, including atherosclerosis. This has led to the conception of endothelial cells as a therapeutic target; indeed, many anti-inflammatory agents already in use target endothelial cells as well as leukocytes (Pober and Sessa, 2007).

Much is known about the molecules and pathways promoting inflammation in endothelial cells, including the involvement of exogenous inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and the critical role played by the NF-κB signaling pathway in orchestrating a pro-inflammatory program in endothelial cells (Kempe et al., 2005; Pober and Sessa, 2007). Much less is known about transcription factors that counterbalance NF-κB and serve as controlling mechanisms against the inflammatory phenotype in ECs, although an inhibitory role has been found for the Krueppel-like factors, notably KLF2 (Rao et al., 2007) and recently KLF11 (Fan et al., 2012).

In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that MEF2C serves as an internal control mechanism in endothelial cells for leukocyte adhesion and the adoption of a pro-inflammatory phenotype. While MEF2C knockdown stimulated leukocyte adhesion and NF-κB activity in endothelial cells, overexpression of MEF2C strongly blocked TNF-α induction of leukocyte adhesion, NF-κB activity, and expression of multiple pro-inflammatory molecules. We therefore conceptualize TNF-α downregulation of MEF2C in endothelial cells (Fig. 1) to be part of the pro-inflammatory program of this cytokine, as our studies suggest that MEF2C can serve as an endogenous inhibitor against leukocyte adhesion under physiologic conditions (downregulation of MEF2C in endothelial cells significantly increases leukocyte adhesion). Importantly, we observed that endothelial-cell specific knockout of MEF2C results in a significant increase in LPS-induced leukocyte adhesion in vivo, highlighting the endothelial cell-specific function of MEF2C with respect to inflammation. This expands the role played by MEF2C in regulating endothelial cells, as we and others have previously demonstrated that MEF2C regulates angiogenic phenotype and program in these cells as well.

Strikingly, we found a strong effect of overexpressing MEF2C in suppressing TNF-α-induced leukocyte adhesion in endothelial cells, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting MEF2C. We examined the effect of MEF2C overexpression on VCAM1, E-selectin, and ICAM1, since leukocyte adhesion to ECs is known to be mediated by endothelial expression of these and other adhesion molecules. The expression of E-selectin, ICAM1 and VCAM1 were significantly inhibited by MEF2C overexpression under both basal conditions and following TNF-α stimulation. Overexpression of MEF2C also inhibited the expression of the pro-inflammatory chemokines IL-8 and MCP1, indicating a broader-based effect of MEF2C on the inflammatory genetic program. Interestingly, and somewhat surprisingly, we did not find an enhancement of ICAM1 and VCAM1 expression after MEF2C knockdown under basal conditions. Conceivably, MEF2C knockdown might result in upregulation of other MEF2 family transcription factors, such as MEF2A, MEF2B, and MEF2D, which might serve to diminish the effect of MEF2C knockdown. Alternatively, ICAM1 and VCAM1 may not be as important in MEF2C’s effect on leukocyte adhesion under basal conditions.

In looking for signaling pathways mediating the effect on these genes, NF-κB was a logical candidate, as it has long been appreciated to be a target of TNF-α and is a major mediator of the effects of this cytokine (Pahl, 1999; Kempe et al., 2005). A heterodimer of p65 and p50 is the major form of NF-κB, and it is preferentially localized in the cytoplasm with inhibitory IκB proteins under quiescent condition (Oeckinghaus and Ghosh, 2009). After stimulation by pro-inflammatory cytokines, IκBs are phosphorylated by IκB kinases and further degraded by proteasomes, causing NF-κB to be released and translocated into nucleus to activate target genes expression (Dekker et al., 2002; Oeckinghaus and Ghosh, 2009; Baker et al., 2011). Numerous studies have shown that the phosphorylation of Serine536 in the transcription activation domain of p65 promotes its nuclear translocation, interaction with CBP/p300, and transcriptional activity (Mattioli et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2005; Perkins, 2006; Wan and Lenardo, 2009). We found that MEF2C overexpression blocked TNF-α-induced nuclear translocation of p65, as well as phosphorylation at the Serine536 position. TNF-α-induced degradation of IκB-α was also attenuated by MEF2C overexpression, which together with inhibition of the phosphorylation of Ser536 likely contribute to the decreased NF-κB nuclear translocation and activation of target gene expression.

In addition to the effects of MEF2C overexpression on the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB, we also examined the effects on KLF2, which is known to play an anti-inflammatory role in ECs (Rao et al., 2007). Interestingly, MEF2 factors have previously been found to bind and transactivate KLF2 promoter (Kumar et al., 2005), and p65 can interact with histone deacetylases 4 to inhibit the ability of MEF2 factors to induce the KLF2 promoter. We found that MEF2C strongly increases KLF2 protein levels in endothelial cells. KLF2 knockdown partially attenuated MEF2C-inhibition of TNF-induced leukocyte adhesion by 39%. KLF2 knockdown had a similar effect in partially rescuing MEF2C’s inhibitory effect on TNF induction of adhesion molecules, including VCAM1 (20%), E-selectin (11%), and ICAM1 (37%). We only observed a partial rescue effect of siKLF2, even though KLF2 mRNA levels were completely inhibited back to control levels (Fig. 7). This indicates to us that MEF2C resides upstream of KLF2 in anti-inflammatory signaling in endothelial cells, and that KLF2 partially mediates MEF2C’s effects although other as yet unidentified MEF2C target genes likely play a role as well. Although KLF2 has received particularly extensive attention for its anti-inflammatory effects, other KLF family members including KLF11 can also regulate inflammation (Fan et al., 2012), and it will be interesting to determine whether these members might also be modulated by MEF2C.

In summary, this study identifies MEF2C as an important homeostatic transcription factor in the control of inflammation in vascular endothelial cells, inhibiting leukocyte recruitment, counterbalancing NF-κB activity, and regulating the expression of multiple pro-inflammatory genes including leukocyte adhesion molecules. These findings expand the current knowledge of the intracellular mechanisms that are available to limit the inflammatory response in endothelial cells. MEF2C therefore serves as a possible therapeutic target for multiple disease conditions characterized by endothelial cell dysfunction and inflammation, including atherosclerosis and diabetic complications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute;

Contract grant number: EY018138, EY022383 and EY022683.

Contract grant sponsor: Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation;

Contract grant number: 17–2011-271.

We thank Dr. Jeffery Molkentin (University of Cincinnati) for providing Ad-MEF2C and Ad-GFP, Dr. Huck-Hui Ng (National University of Singapore) for the KLF2 antibody and Dr. John Schwarz (Albany Medical College) for providing the mef2c conditional knockout mice. We also thank Jing Tian (Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, USA) for statistical analysis. This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (EY018138, EY022383 and EY022683; EJD), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, and a generous gift from Cindy and Jeong H. Kim, Ph.D. EJD is a recipient of an RPB Career Development Award.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

Literature Cited

- Al-Shabrawey M, Rojas M, Sanders T, Behzadian A, El-Remessy A, Bartoli M, Parpia AK, Liou G, Caldwell RB. Role of NADPH oxidase in retinal vascular inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3239–3244. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam J, Cook JL. How many transcription factors does it take to turn on the heme oxygenase-1 gene? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:166–174. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0340TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RG, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011;13:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi W, Drake CJ, Schwarz JJ. The transcription factor MEF2C-null mouse exhibits complex vascular malformations and reduced cardiac expression of angiopoietin 1 and VEGF. Dev Biol. 1999;211:255–267. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell TS, Christman JW. The role of nuclear factor-kappa B in cytokine gene regulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:3–9. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.1.f132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LF, Williams SA, Mu Y, Nakano H, Duerr JM, Buckbinder L, Greene WC. NF-kappaB RelA phosphorylation regulates RelA acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7966–7975. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.7966-7975.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins T, Read MA, Neish AS, Whitley MZ, Thanos D, Maniatis T. Transcriptional regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules: NF-kappaB and cytokine-inducible enhancers. FASEBJ. 1995;9:899–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Mills JM, Deem TL. Active participation of endothelial cells in inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:487–495. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker RJ, van Soest S, Fontijn RD, Salamanca S, de Groot PG, VanBavel E, Pannekoek H, Horrevoets AJ. Prolonged fluid shear stress induces a distinct set of endothelial cell genes, most specifically lung Kruppel-like factor (KLF2) Blood. 2002;100:1689–1698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Guo Y, Zhang J, Subramaniam M, Song CZ, Urrutia R, Chen YE. Kruppel-Like Factor-11, a Transcription Factor Involved in Diabetes Mellitus, Suppresses Endothelial Cell Activation via the Nuclear Factor-kappaB Signaling Pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2981–2988. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DN, Senchenkova E. Inflammation and the Microcirculation. San Rafael (CA): 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TA, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Mendell JT, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1516–1521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann E, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Holtmann H, Kracht M. Multiple control of interleukin-8 gene expression. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2002;72:847–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe S, Kestler H, Lasar A, Wirth T. NF-kappaB controls the global pro-inflammatory response in endothelial cells: Evidence for the regulation of a pro-atherogenic program. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5308–5319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Lin Z, SenBanerjee S, Jain MK. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated reduction of KLF2 is due to inhibition of MEF2 by NF-kappaB and histone deacetylases. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5893–5903. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.5893-5903.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvietys PR, Granger DN. Role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in the vascular responses to inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:556–592. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Lu J, Yanagisawa H, Webb R, Lyons GE, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Requirement of the MADS-box transcription factor MEF2C for vascular development. Development. 1998;125:4565–4574. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.22.4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Schwarz J, Bucana C, Olson EN. Control of mouse cardiac morphogenesis and myogenesis by transcription factor MEF2C. Science. 1997;276:1404–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti D, Xu Z, Duh EJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces MEF2C and MEF2-dependent activity in endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3640–3648. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli I, Sebald A, Bucher C, Charles RP, Nakano H, Doi T, Kracht M, Schmitz ML. Transient and selective NF-kappa B p65 serine 536 phosphorylation induced by T cell costimulation is mediated by I kappa B kinase beta and controls the kinetics of p65 nuclear import. J Immunol. 2004;172:6336–6344. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai N, Thimmulappa RK, Cano M, Fujihara M, Izumi-Nagai K, Kong X, Sporn MB, Kensler TW, Biswal S, Handa JT. Nrf2 is a critical modulator of the innate immune response in a model of uveitis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S. The NF-kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000034. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins ND. Post-translational modifications regulating the activity and function of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:6717–6730. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pober JS, Sessa WC. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:803–815. doi: 10.1038/nri2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff MJ, Olson EN. MEF2: a central regulator of diverse developmental programs. Development. 2007;134:4131–4140. doi: 10.1242/dev.008367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RM, Yang L, Garcia-Cardena G, Luscinskas FW. Endothelial-dependent mechanisms of leukocyte recruitment to the vascular wall. Circ Res. 2007;101:234–247. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151860b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth SA, Shah S, MacEwan DJ. TNF mediates the sustained activation of Nrf2 in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2011;187:702–707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore P, Sharrocks AD. The MADS-box family of transcription factors. Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtzel C, Testori J, Schweighofer B, Bilban M, Hofer E. The Transcription Factor MEF2C Negatively Controls Angiogenic Sprouting of Endothelial Cells Depending on Oxygen. PloS one. 2014;9:e101521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan F, Lenardo MJ. Specification of DNA binding activity of NF-kappaB proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000067. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Dang J, Wang H, Allgayer H, Murrell GA, Boyd D. Identification of a novel nuclear factor-kappaB sequence involved in expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:3248–3254. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Cao S, Wang L, Xu R, Chen G, Xu Q. VEGF promotes the transcription of the human PRL-3 gene in HUVEC through transcription factor MEF2C. PloS one. 2011;6:e27165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Gong NL, Bodi I, Aronow BJ, Backx PH, Molkentin JD. Myocyte enhancer factors 2A and 2C induce dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9152–9162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Gong J, Maiti D, Vong L, Wu L, Schwarz JJ, Duh EJ. MEF2C ablation in endothelial cells reduces retinal vessel loss and suppresses pathologic retinal neovascularization in oxygen-induced retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:2548–2560. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Baban B, Rojas M, Tofigh S, Virmani SK, Patel C, Behzadian MA, Romero MJ, Caldwell RW, Caldwell RB. Arginase activity mediates retinal inflammation in endotoxin-induced uveitis. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:891–902. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Connell MC, MacEwan DJ. TNFR1-induced NF-kappaB, but not ERK, p38MAPK or JNK activation, mediates TNF-induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression on endothelial cells. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1238–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.