Abstract

By 2021, health care spending is projected to grow to 19.6% of the GDP, likely crowding out spending in other areas. The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) attempts to curb health care spending by incentivizing high-value care through the creation of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), which assume financial risk for patient outcomes. With this financial risk, health systems creating ACOs will be motivated to pursue innovative care models that maximize the value of care. Palliative care, as an emerging field with a growing evidence base, is positioned to improve value in ACOs by increasing high-quality care and decreasing costs for the sickest patients. ACO leaders may find palliative care input valuable in optimizing high-quality patient-centered care in the accountable care environment; however, palliative care clinicians will need to adopt new models that extrapolate their direct patient care skills to population management strategies. We propose that palliative care specialists take on responsibilities for working with ACO leaders to broaden their mission for systemwide palliative care for appropriate patients by prospectively identifying patients with a high risk of death, high symptom burden, and/or significant psychosocial dysfunction, and developing targeted, “triggered” interventions to enhance patient-centered, goal-consistent, coordinated care. Developing these new population management competencies is a critical role for palliative care teams in the ACO environment.

Introduction

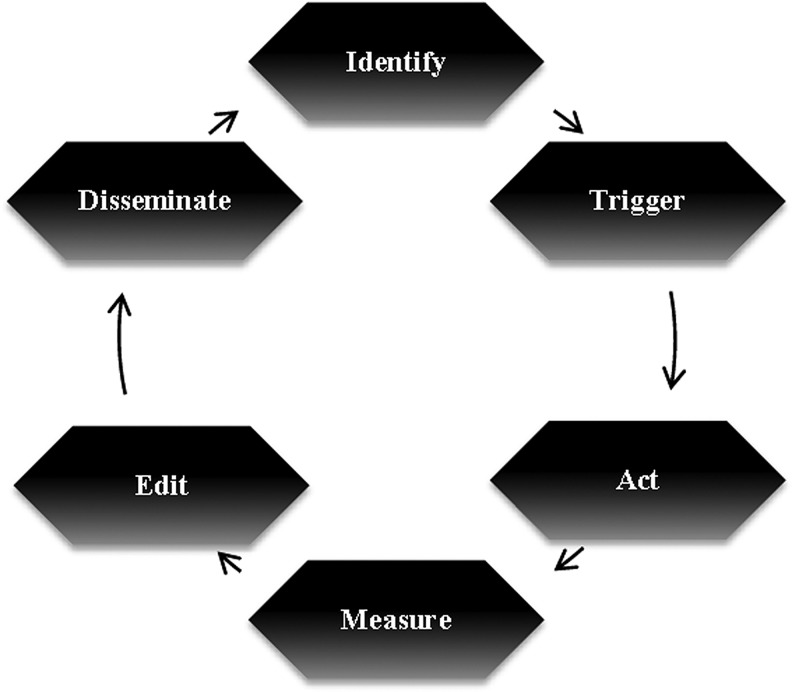

Improving value by increasing high-quality care and decreasing costs is one of the missions of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), and palliative care is uniquely poised to help achieve this aim for many of the sickest patients. However, this requires new palliative care strategies that extend beyond services to individual patients to taking on responsibilities in population-based management for seriously ill patients. In this paper we first outline the current environment that makes this approach necessary, and then propose six steps that are critical to any population-based health care delivery model: Identify, Trigger, Act, Measure, Edit, and Disseminate (iTAMED).

Current Health Care Spending Is Unsustainable

In 2012, the United States is estimated to have spent $2.8 trillion on health care, representing 17.2% of the GDP.4 With Medicare and Medicaid predicted to have an average annual growth rate of 6.0% over the next decade, health care spending is estimated to represent 19.3% of the GDP by 2023.5 Such spending may crowd out important investments in infrastructure and education, and other areas of the economy may also suffer as U.S. citizens and companies spend greater portions of income on health care.7

Spending Increases as People Approach the End of Life

Interventions aimed at reducing health care spending often focus on areas where health care dollars are spent disproportionately across a population. Because it accounts for approximately one-quarter of Medicare's spending, care provided during the last year of life has been cited as an area of potential intervention.8 However, simply targeting spending at the end of life because it is a significant portion of Medicare's spending risks underserving patients at their time of greatest need. The sickest patients need care that is often expensive and intensive, whether that is ICU care or hospice care. Yet, the considerable spending at the end of life on interventions that provide minimal or no benefit and that are not consistent with patient preferences offers a good target for intervention.

High Value Care Is an Appropriate Goal

The “value” of care, defined as the quality of care in relation to its cost, offers a framework that can identify appropriate, targeted interventions that align spending with desired patient-centered outcomes. On a national scale, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), through its creation of ACOs, attempts to promote and incentivize high-value patient care rather than solely focusing on the “cost” of care, which can erode patients' trust and confidence in the motivations of health care systems. High-value care and efficiency are incentivized in ACOs by aligning reimbursement with patient outcomes through capitated and/or aggregated payments. With ACOs taking on significant financial risk for patients, there is increasing pressure to maximize quality, minimize costs, and increase value.11

Quality of Care at the End of Life

Currently, many aspects of end-of-life care are of low value. Care is not well aligned with patient priorities and is frequently costly and without benefit.13 Many elements of care that are valued by patients (e.g., symptom control) are not routinely available.13 Family members' perceptions of end-of-life care for a loved one were that a quarter of family members perceived that patients with pain or dyspnea did not receive adequate symptom control and over half felt their loved one did not receive enough emotional support.14

Patterns of health care utilization at the end of life also diverge significantly from patient preferences. While the vast majority of patients approaching the end of life prefer to die at home, nearly 30% of advanced cancer patients die in a hospital, and there is relatively little correlation between patients' preferred and actual place of death.15,17 Recent data show that although a lower proportion of Medicare beneficiaries are dying in acute care hospitals, both ICU use and the rate of health care transitions in the last month of life are increasing.19 Patients dying in an ICU or hospital have lower quality of life, with more physical and emotional distress, compared to patients dying at home with hospice.17 Even patients with cancer who enroll in hospice do not fully realize its benefits given that they spend an average of only 8.7 days in hospice during the last month of life.13

Palliative Care Provides High-Value Care

Multiple randomized-controlled trials of specialist palliative care team interventions have shown improved outcomes, including improved quality of life,20–24 greater satisfaction with care,25,26 increased hospice utilization,20,26 reductions in family distress,24 and even improved survival.20 Inpatient palliative care services have been associated with improved communication between patients and doctors;27 enhanced patient perception of emotional support;27 higher patient satisfaction;26 and decreased pain,28–31 dyspnea,28,31 and nausea.28

The integration of palliative care into health systems has led to significant improvements in the quality of patient care while also reducing costs.32,33 Inpatient palliative care consultation has been associated with reduced hospital length of stay31 and length of stay in the ICU;26,34 and decreased readmission rates,31 use of the emergency department,29 and ICU admissions.26,35 Compared to matched controls, patients who had a palliative care consult demonstrated direct costs savings of $1,696 per admission, which has been estimated to be 19.2% lower total costs per admission.28,32 Studies looking at costs before and after launching an inpatient palliative care consult service in a large, academic medical center found an estimated savings of $2.2 million annually.31 In addition, home-based palliative care has been shown to be associated with reduced total number of hospitalizations and probability of 30-day readmission,36 and reduced costs, with savings ranging from 25% to 45% of usual care costs, representing savings from $4,172 to $11,325 per case.25,37,38 In addition to team-based specialist palliative care, a la carte palliative care interventions (e.g., effective discussions about code status, goals of care, or symptom management) are regularly carried out by nonpalliative care clinicians.39 Effectively meeting patient needs across an entire population requires specialist palliative care, using the entire team, and generalist palliative care interventions, often conducted by individual clinicians on focused problems.

Access to Specialized Palliative Care Is Limited

Despite the high value of palliative care, limited access has prevented the full realization of its benefits. Although the prevalence of palliative care programs in hospitals with 50 beds or more has increased from 658 hospitals (24%) in 2000 to 1692 hospitals (67%) in 2011, individuals living in the southern United States and populations receiving care from community-based and safety net hospital are especially limited in their access to specialized palliative care.40 While few data are available, access to palliative care in community or home settings is even more limited.41,42 A shortage of board-certified physicians in hospice and palliative medicine is a major barrier to access.43 Because of this shortage, generalist physicians will need to develop competencies to practice primary palliative care, with backup and support from palliative care specialists.44 The distinctions between primary palliative care and specialist palliative care are noted below:

Representative Skill Sets for Primary and Specialty Palliative Care34

| Primary palliative care |

| Basic management of pain and symptoms |

| Basic management of depression and anxiety |

| Basic discussions about |

| Prognosis |

| Goals of treatment |

| Suffering |

| Code status |

| Specialty palliative care |

| Management of refractory pain or other symptoms |

| Management of more complex depression, anxiety, grief, and existential distress |

| Assistance with conflict resolution regarding goals or methods of treatment |

| Within families |

| Between staff and families |

| Among treatment teams |

| Assistance in addressing cases of near futility |

The Role of Palliative Care in ACOs

In spite of the limited number of palliative care clinicians, the expansion of ACOs presents opportunities for both ACOs and palliative care teams to extend their impact. Palliative care is uniquely positioned to support value through both direct clinical care of individual patients and development of systems of care for populations of the sickest (and potentially most expensive) patients cared for within ACOs. “Population management” or “population-based management” have been used to describe many interventions and models, but have yet to be consistently defined.45–47

We define population management as a health care delivery model that strives to enhance clinical and financial outcomes for defined populations within health care networks. In the context of palliative care, we propose that population management should include: (1) identifying high-risk patients using data (e.g., risk score/stratification; greater than three hospitalizations in a year; negative answer to the “surprise question,” Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next year? etc.) and (2) selecting a “targeted” intervention to match patients' level of need. High-risk patients may be defined according to the priorities and agenda of the ACO institution and may include, for example, patients with limited prognoses, high health care utilization, elevated symptom burden, or multiple comorbidities.

A Process for Developing Population-Management Strategies

Adopting new responsibilities in population-based management requires a novel framework of practice in palliative medicine. We propose six steps that are critical to any population-based health care delivery model: Identify, Trigger, Act, Measure, Edit, and Disseminate (iTAMED).

Identify

Systematic identification of patients for whom specialist and/or primary palliative care interventions are likely to improve quality of life and reduce cost is essential in setting up a successful population management program. Unfortunately, widely accepted criteria for identifying patients who would most benefit from palliative care have not been developed. However, patients with limited prognosis, high health care utilization, or poorly controlled symptoms represent populations where palliative care interventions can have high impact.48

For example, hospitalization, in some populations (e.g., CHF, advanced gastrointestinal malignancies), often represents an inflection point in the disease trajectory, indicating a limited prognosis, and can be a useful indicator for patients at a high risk of mortality.49 The “surprise question” is a validated single-item method for identifying advanced cancer and dialysis patients at high risk of dying within a year.50,51 A physician answering “No” to the question “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next year?” confers an odds ratio of death of 7.9 for patients with cancer50,51 and 3.5 for dialysis patients.50

The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) has published criteria for initiating palliative care interventions for hospitalized patients.52 Such rubrics are helpful examples of integrating multiple pieces of clinical and administrative data to identify a high-risk population.

Risk prediction algorithms can be used to stratify patients into risk categories, which serve as a basis for deploying resources for complex patients. Private companies have proprietary models based on claims data to assist with risk stratification.43 Other criteria-based tools include the Cancer, Admissions, Residence in Nursing Home, Intensive Care Unit with Multiorgan Failure, Noncancer Hospice Guidelines (CARING) criteria44 and the palliative care screening algorithm used within the Veterans Affairs hospitals. Popular prognostic tools such as ePrognosis (2012) can also be utilized for appropriate populations.45

Electronic medical records (EMRs) with advanced analytics can flag patients at high risk of death or high resource utilization, thereby identifying patients where palliative care interventions can have impact. EMR-integrated risk models can be based on prognostic indicators such as number of hospitalizations within a year and the presence of advanced chronic disease (metastatic cancer,46 ESRD requiring dialysis,47–49 COPD requiring home oxygen,50–52 Stage D CHF,53 end-stage dementia,54 and functional decline54). Functional status, a consistent predictor of mortality in older adults, is another useful component for identifying mortality risk beyond that provided by diagnoses or utilization measures,55 but is frequently not evaluated or captured reliably in standard electronic records.

Trigger

Once an appropriate population of patients has been identified, a system for triggering or prompting clinicians to apply the appropriate interventions must be in place. While the precise method of triggering will depend on the intervention being delivered, implementing triggers requires working with experts in information technology (IT), quality improvement, and clinical operations to develop systems that work within existing clinical workflows.

Input and feedback from the clinicians who are triggered minimizes barriers and enhances adoption. The institutional changes in culture and incentives that occur under ACO models provide a key opportunity to align triggers with the priorities and values of institutions and individuals.

Processes for triggering can include e-mail reminders, flags integrated into the EMR, and in-person reminders. In a study of patients with incurable lung cancer, Temel et al. showed that electronic prompts for documenting code status at the time of initiating new chemotherapy increased code status documentation.56 Another successful model for increasing completion of advance directives utilized both physician and patient triggers.57

Act

Once at-risk patients have been identified and a triggering mechanism has been developed to activate the clinician, the team must deploy an evidence-based intervention. Several studies in the palliative care literature have described interventions that have improved the quality of patient care,12,16,27,58–60 reduced health care utilization,16,27,59,60 and reduced costs.16,27 However, it is important to note that most of these interventions are multifaceted, making it challenging to determine which components are responsible for positive outcomes.

Despite this limitation, some components have been present in several of the successful multifaceted interventions and thus may be effective interventions to consider in a population management model. These include IT and EMR innovation to identify patients and track outcomes,56,61 patient/family education focused on self-management at home,58 access to telephone nursing support for symptom management at home,12,13 interdisciplinary case review for care coordination,59 and home-based palliative care visits for acute symptom management.16

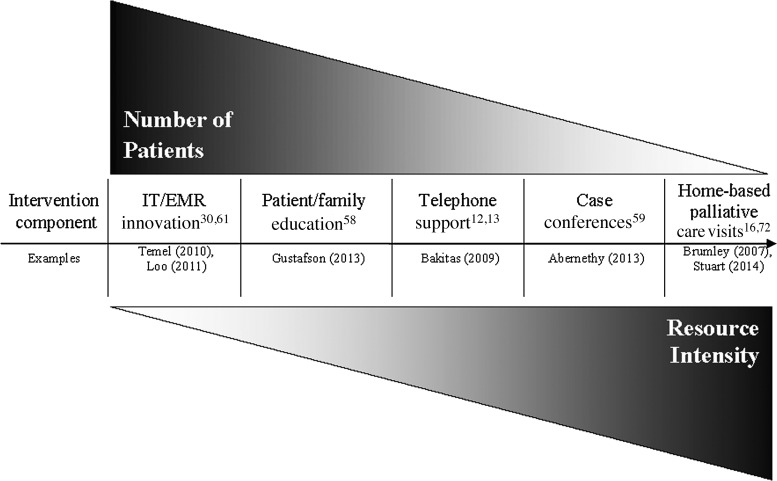

When deploying any of these intervention components, the number of patients an intervention component can reach is typically inversely related to intensity of the resources needed to provide the service. Figure 1 depicts this relationship and describes intervention components that might be included in a population management program in relationship to the number of patients they could serve and the resource intensity involved. The figure further describes the interventions and outlines outcomes that have been measured in these studies.

FIG. 1.

Spectrum of potential interventions for palliative care delivery in populations. IT, information technology; EMR, electronic medical record.

Measure

Establishing and monitoring appropriate, meaningful, and actionable metrics is essential in population management. Routine measurements, as much as possible, should focus on processes and outcomes that can be ascertained from existing databases. The National Quality Forum has published a strategy for performance measures that reflects a shift towards a population-based perspective in palliative care,62 identifying care coordination, appropriateness of care, and costs of care as essential aspects of evaluation.

Measured outcomes must incorporate both sides of the value equation, including both quality and costs. Established quality measures should reflect clinical outcomes (e.g., pain scores and quality of life measures) and patient- and family-reported outcomes (e.g., communication with the medical team, access to team and advice, and emotional support). Cost measures need to include both utilization (ED visits, ICU days, hospitalizations, chemotherapy in the last month of life, mean days of hospice) and health care spending. While such measures are difficult to obtain, they are crucial in measuring quality and are required in performance standards that ACOs must meet for shared savings.63

When data are available, they should be shared to promote change (e.g., ongoing provider performance reports, notifying outlier providers of their status and providing alternatives and coaching for clinicians who underperform). For example, a provider might be alerted when they have a disproportionate number of patients with hospice stays less than three days64 compared to other clinicians caring for similar populations. Systems such as these have been noted to improve outcomes (e.g., Intermountain Health Care), but require substantial investment in infrastructure.65

Edit

The ability to edit and adapt models in response to process and outcomes data is crucial in developing successful population management programs. Many interventions can be simplified as experience is gained, making them more usable and scalable. Process data can be used to jettison parts of the intervention that do not add value. This “honing” of the intervention is critical in building sustainable population management systems.

Because it is difficult to tease apart the degree to which any individual component of an intervention contributes to improved quality of care and reduced costs, it is important for ACOs to design programs that will work for their systems and prepare to alter them according to performance on process and outcome measures. For example, during a quality improvement project at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute66 investigating the impact of a serious illness care planning guide for cancer patients with a poor prognosis, we adapted our patient identification process in response to clinician preference, both to keep the clinicians engaged and to simplify the process. Clinicians who had initially wanted to identify patients using chemotherapy regimens as markers of prognosis found that not all of those patients were appropriate for the intervention; thus the clinicians asked to use the “surprise question” to identify patients. This flexibility and adjustment helped the identification process run more smoothly and improved buy-in from the oncologists.

FIG. 2.

iTAMED – identify, trigger, act, measure, edit, and disseminate.

Disseminate

As successful population management programs emerge, opportunities arise to replicate them in other populations, age groups, settings, and regions. In replicating programs, it is important to hone in on the key components of interventions that contribute to desired outcomes and to identify key benchmark measures that ensure a basic level of quality. The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is one example of a geriatric intervention that started as a program to treat a very specific population, elderly Chinese men in San Francisco, and has been successfully expanded into PACE programs across 30 states. Even as it has expanded, it has persistently been linked to lower hospitalization rates and 30-day readmission rates when compared to similar populations without PACE services.67 Geriatric and palliative care teams can plan together for population-based care for older patients.

Education to improve the primary palliative care skills of all physicians42,68,69 is an essential part of every step of population-based palliative care, and it is especially important in disseminating interventions. By investing in training nonpalliative care physicians to develop generalist-level palliative care competencies,34 palliative care teams will help assure broader access to palliative care services, and will be better able to focus on patients with complex needs; while direct, basic palliative care services are provided to most patients by primary physicians.34 Division of responsibility and appropriate resource allocation help reduce the inefficiencies that ACOs are meant to target.

Limitations and Caution

Caution in developing these programs is necessary. Ensuring that programs that work in one setting are carefully and systematically scaled to the next larger setting is critical. The Liverpool Care Pathway, perhaps the most widely used care pathway in palliative care, for example, was abolished after an independent review showed inadequacies in training and implementation of the pathway at different sites and public perception that it was not patient-centered.70,71 The failure of this initiative highlights the need for ongoing training and support, as well as regular auditing.

Focusing on population management may represent significant cultural change for palliative care programs and institutions and thus may be met with resistance in some settings. At the same time, some high-volume, mature palliative care teams may consider a focus on systemwide improvement in addition to patient-by-patient care; these teams may experience enhanced efficacy and purpose.

Our limited ability to reliably predict prognosis is also a challenge in identifying patients appropriate for palliative care intervention. Even with unreliable predictions, however, there are interventions for seriously ill patients that appear to improve outcomes, without adverse effects. Early discussion about end-of-life goals and preferences is one such intervention;11 the rationale for this intervention is that quality of life is enhanced when patients are engaged in discussions about serious illness care planning. There is no evidence that earlier discussions are harmful, even if the patient survives for longer than expected.

Ongoing resistance to palliative care among some specialists and the general population may also limit the ability to optimally integrate palliative care into ACOs. Focusing on ways palliative care improves quality of life and patient-centered care, rather than on financial outcomes, and on what palliative care offers (“an extra layer of support”) rather than what it takes away (“withdrawal of life-sustaining care”) may help ACOs view and present palliative care as a centerpiece of their approach to high-value care.

Conclusions

Palliative care clinicians and ACO leadership can partner together to change the way health care is delivered. The iTAMED model provides a structure for designing a population management program incorporating core principles from palliative care. While multiple studies have demonstrated that components of population-based palliative care interventions improve the quality of patient care, there is a dearth of research on utilization and cost outcomes. We do not yet have adequate data to make recommendations on which population management strategies are most effective. Rigorous trials with data about patient outcomes, costs, and utilization are critical to the next phase in the development of palliative care population management.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Bernacki is supported by Geriatric Academic Career Award K01HP20462.

Table 1.

Potential Population Management Interventions and Outcomes

| Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Population | Intervention components | Quality of patient care | Health care utilization | Cost |

| aTemel et al. 2013 Electronic prompt to improve outpatient code status documentation for patients with advanced lung cancer | Incurable lung cancer (NSCLC or small/large-cell neuro-endocrine) Within 8 weeks of receiving first dose of IV chemotherapy Had ECOG performance from 0–2 |

E-mail reminders sent 1) At the first outpatient visit after the patient had enrolled 2) On the day of an outpatient appointment immediately after the start of each new line of chemotherapy until a code status was documented in the EHR |

Greater number of documented code status modules completed† | No health care utilization analysis conducted | No cost analysis conducted |

| bLoo et al. 2011 Electronic medical record reminders and panel management to improve primary care of elderly patients | Patients 65 years of age or older Faculty PCP at site ≥1 visit to practice in 18 months prior to study |

1) Compared: Standard EMR EMR reminders for advance directives, aspirin chemoprevention, Beers medication alerts, fall screening, osteoporosis screening, and vaccinations EMR reminders+assistance from panel manager (assessed whether care had already been received, and if not, reminded the patient of recommended care) |

EMR reminder: -Increased influenza vaccination‡ -Increased pneumococcal vaccination* EMR reminder+panel manager: -Increased rate of designated health care proxy‡ -Increased rate of bone density screening† -Increased influenza vaccination‡ -Increased pneumococcal vaccination† |

No health care utilization analysis conducted | No cost analysis conducted |

| cGustafson et al. 2013 An eHealth system supporting palliative care for patients with non–small cell lung cancer | Multisite in East, Midwest, and Southwest U.S. NSCLC Stage IIIA-IV and primary caregiver willing to participate; life expectancy ≥4 months |

CHESS website 1) Provides lung cancer, care giving, and bereavement information 2) Serves as channel to communicate with peers, experts, clinicians 3) Provides feedback to users based on their input and established algorithms/pathways 4) Provides tools to improve caregiving experience Clinicians alerted if patients report poor health status and receive patient questions |

Caregivers reported lower physical symptom distress in patients† Improved patient survival† |

No health care utilization analysis conducted | No cost analysis conducted |

| dBakitas et al. 2009 Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer | Dartmouth Norris Cotton Cancer Center – Lebanon, NH Patients with a life-limiting cancer diagnosis with prognosis of approximately 1 year |

Nurse conducted telephone curriculum of 4 structured education sessions with patients Monthly telephone-based follow-up with distress assessment Monthly group shared medical appointments |

Higher quality of life* Less symptom intensity Less depressed mood* |

No difference in number of days in hospital or ICU No difference in number of ED visits |

No cost analysis conducted |

| eAbernethy et al. 2012 Delivery strategies to optimize resource utilization and performance status for patients with advanced life-limiting illness | South Australia Any patient referred to palliative care service who was experiencing pain in last 3 months and expected to live >48 hours with a life-limiting illness |

Compared: 1) Case conferences 2) GP education outreach 3) Patient/caregiver education 4) Standard care |

Case conference was associated with maintaining performance status* Case conference* and patient/caregiver education* associated with maintenance of performance status if the patient's initial performance status represented ≥70% decline from baseline. Reduction in total symptoms burden with patient/caregiver education* |

Significant reduction in number of hospitalizations with case conference† | No cost analysis conducted |

| fBrumley et al. 2007 Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care | Kaiser Permanente in Hawaii and Colorado Patients with CHF, COPD, or cancer and prognosis of ≤1 year plus ≥1 hospital or ED visits in last year |

Home-based interdisciplinary care Palliative care team coordinates care across all settings Patient and family education 24/7 telephone RN service |

Improved satisfaction at 30 days* and at 90 days* More likely to die at home‡ Note: There was a strong trend toward shorter survival for those in the palliative care group (196 days vs. 242 days) |

Fewer ED visits† Fewer hospitalizations‡ (Linear regression showed intervention reduced hospital days‡ and ED visits*) |

Reduction in total costs of care‡ Reduction in daily costs* Mean reduction of $7,552 (33%) for intervention group |

| gStuart et al. 2013 Advance care model honors dignity, integrated health system for seriously ill people and loved ones | Sutter Health Patients with advance disease who meet any following: -≥1 chronic dx -Questionable benefit from further aggressive treatment -Functional/nutritional decline in last 30 days -Hospice eligible but not ready for hospice -Frequent ED visits and hospitalizations in last 6 months |

1) Care managers assist in advance directives, personal health record tool, complete POLST 2) Care liaisons and social workers assist with discharge planning and transitional care 3) Home-based care when needed 4) Telephone calls to assess patient, trigger alerts to clinicians if problems 5) Transition to hospice if desired and appropriate |

High satisfaction with care | Increased use of hospice Fewer hospitalizations Fewer ICU days Reduced LOS for hospitalizations Reduction in physician office visits |

Cost savings of $760 per enrollee per month |

Statistically significant p<0.05

†Statistically significant p<0.01

‡Statistically significant p<0.001

CHESS, Center for Health Enhancement System Studies; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EMR, electronic medical record; LOS, length of stay; NSCLC, nonsmall cell lung cancer; PCP, primary care provider; POLST, physicians orders for life sustaining treatment.

References

- 1.Martin AB, Hartman M, Whittle L, Catlin A: National health spending in 2012: Rate of health spending growth remained low for the fourth consecutive year. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sisko AM, Keehan SP, Cuckler GA, et al. : National health expenditure projections, 2013–23: Faster growth expected with expanded coverage and improving economy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1841–1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sood N, Ghosh A, Escarse JJ: The Effect of Health Care Cost Growth on the U.S. Economy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley GF, Lubitz JD: Long-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. Health Serv Res 2010;45:565–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutler DM, Ghosh K: The potential for cost savings through bundled episode payments. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1075–1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Chang C, et al. : The Dartmouth Atlas Project, 2010. www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/Cancer_report_11_16_10.pdf (Last accessed October5, 2014.)

- 7.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. : Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA 2004;291:88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer S, Min SJ, Cervantes L, Kutner J: Where do you want to spend your last days of life? Low concordance between preferred and actual site of death among hospitalized adults. J Hosp Med 2013;8:178–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. : Place of death: Correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4457–4464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. : Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA 2013;309:470–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: Baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:75–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ: The comprehensive care team: A controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyers FJ, Carducci M, Loscalzo MJ, et al. : Effects of a problem-solving intervention (COPE) on quality of life for patients with advanced cancer on clinical trials and their caregivers: Simultaneous care educational intervention (SCEI): Linking palliation and clinical trials. J Palliat Med 2011;14:465–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. : Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. : Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized control trial. J Palliat Med 2008;11:180–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. : Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:593–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanson LC, Usher B, Spragens L, Bernard S: Clinical and economic impact of palliative care consultation. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:340–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Mahony S, Blank AE, Zallman L, Selwyn PA: The benefits of a hospital-based inpatient palliative care consultation service: Preliminary outcome data. J Palliat Med 2005;8:1033–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elsayem A, Smith ML, Parmley L, et al. : Impact of a palliative care service on in-hospital mortality in a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 2006;9:894–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciemins EL, Blum L, Nunley M, et al. : The economic and clinical impact of an inpatient palliative care consultation service: A multifaceted approach. J Palliat Med 2007;10:1347–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. : Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1783–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith TJ, Cassel JB: Cost and non-clinical outcomes of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:32–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, et al. : Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: Effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med 2007;35:1530–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. : Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med 2006;9:855–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukas L, Foltz C, Paxton H: Hospital outcomes for a home-based palliative medicine consulting service. J Palliat Med 2013;16:179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA: Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med 2003;6:715–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engelhardt JB, McClive-Reed KP, Toseland RW, et al. : Effects of a program for coordinated care of advanced illness on patients, surrogates, and health care costs: A randomized trial. Am J Manag Care 2006;12:93–100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. : Code status documentation in the outpatient electronic medical records of patients with metastatic cancer. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:150–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Center to Advance Palliative Care. Center to Advance Palliative Care, CAPC Growth Analysis, 2013. www.capc.org/capc-growth-analysis-snapshot-2013.pdf (Last accessed January23, 2013.)

- 32.Meier DE: Increased access to palliative care and hospice services: Opportunities to improve value in health care. Milbank Quarterly 2011;89:343–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lupu D: Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:899–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quill TE, Abernethy AP: Generalist plus specialist palliative care: Creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foote SM: Population-based disease management under fee-for-service Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). Suppl Web Exclusives 2003;W3:342–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen EH, Bodenheimer T: Improving population health through team-based panel management: Comment on “Electronic medical record reminders and panel management to improve primary care of elderly patients.” Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1558–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eggleston EM, Finkelstein JA: Finding the role of health care in population health. JAMA 2014;311:797–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes MT, Smith TJ: The growth of palliative care in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:459–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks GA, Abrams TA, Meyerhardt JA, et al. : Identification of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in patients with GI cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:496–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, et al. : Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:1379–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, et al. : Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2010;13:837–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weissman DE, Meier DE: Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: A consensus report from the center to advance palliative care. J Palliat Med 2011;14:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verisk Health. Enterprise Analytics. www.veriskhealth.com/solutions/enterprise-analytics/dxcg-intelligence (Last accessed September10, 2013.)

- 44.Fischer SM, Gozansky WS, Sauaia A, et al. : A practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: The CARING criteria. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;31:285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yourman LC, Lee SJ, Schonberg MA, et al. : Prognostic indices for older adults: A systematic review. JAMA 2012;307:182–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishnan M, Temel J, Wright A, et al. : Predicting life expectancy in patients with advanced incurable cancer. J Support Oncol 2013;11:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen LM, Ruthazer R, Moss AH, Germain MJ: Predicting six-month mortality for patients who are on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:72–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J, Huang Z, Gilbertson DT, et al. : An improved comorbidity index for outcome analyses among dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2010;77:141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. : Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1206–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Groenewegen KH, Schols AM, Wouters EF: Mortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD. Chest 2003;124:459–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elkington H, White P, Addington-Hall J, et al. : The health care needs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in the last year of life. Palliat Med 2005;19:485–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heffner JE, Fahy B, Hilling L, Barbieri C: Attitudes regarding advance directives among patients in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1735–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, et al. : The Seattle Heart Failure Model: Prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation 2006;113:1424–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, et al. : Prediction of 6-month survival of nursing home residents with advanced dementia using ADEPT vs hospice eligibility guidelines. JAMA 2010;304:1929–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, Covinsky KE: Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA 2006;295:801–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Temel JS, Greer JA, Gallagher ER, et al. : Electronic prompt to improve outpatient code status documentation for patients with advanced lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:710–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heiman H, Bates DW, Fairchild D, et al. : Improving completion of advance directives in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Med 2004;117:318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gustafson DH, Dubenske LL, Namkoong K, et al. : An eHealth system supporting palliative care for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A randomized trial. Cancer 2013;119:1744–1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Shelby-James T, et al. : Delivery strategies to optimize resource utilization and performance status for patients with advanced life-limiting illness: Results from the “palliative care trial” [ISRCTN81117481]. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:488–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Engelhardt JB, Rizzo VM, Della Penna RD, et al. : Effectiveness of care coordination and health counseling in advancing illness. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:817–825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loo TS, Davis RB, Lipsitz LA, et al. : Electronic medical record reminders and panel management to improve primary care of elderly patients. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1552–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Quality Forum: Performance Measurement Coordination Strategy for Hospice and Palliative Care. National Quality Forum, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quality Measurement & Health Assessment Group, Center for Clinical Standards & Quality, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid: Accountable Care Organization 2013 Progam Analysis: Quality Performance Standards Narrative Measure Specifications. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferrell BR: Late referrals to palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2588–2589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.James BC, Savitz LA: How Intermountain trimmed health care costs through robust quality improvement efforts. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1185–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernacki RE, Block SD: Serious illness communications checklist. Virtual Mentor 2013;15:1045–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Segelman M, Szydlowski J, Kinosian B, et al. : Hospitalizations in the program of all-inclusive care for the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.von Gunten CF: Who should palliative medicine be asked to see? J Palliat Med 2011;14:2–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.von Gunten CF: Secondary and tertiary palliative care in US hospitals. JAMA 2002;287:875–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chinthapalli K: The birth and death of the Liverpool care pathway. BMJ 2013;347:f4669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hawkes N: Liverpool care pathway is scrapped after review finds it was not well used. BMJ 2013;347:f4568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stuart B. Advanced care: Provider issues, health system buy-in, and best practices. Public Pol Aging Report 2014;24:102–104 [Google Scholar]