Abstract

Objectives

Our objectives were to assess the magnitude of the disparity in lumbar spine bone mineral density (LSBMD) Z-scores generated by different reference databases and to evaluate whether the relationship between LSBMD Z-scores and vertebral fractures (VF) varies by choice of database.

Patients and Design

Children with leukemia underwent LSBMD by cross-calibrated dual energy x-ray absorptiometry, with Z-scores generated according to Hologic and Lunar databases. VF were assessed by the Genant method on spine radiographs. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between fractures and LSBMD Z-scores. Net reclassification improvement (NRI) and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were calculated to assess the predictive accuracy of LSBMD Z-scores for VF.

Results

For the 186 children from 0–18 years of age, 6 different age ranges were studied. The Z-scores generated for the 0 to 18 group were highly correlated (r ≥ 0.90), but the proportion of children with LSBMD Z-scores ≤ −2.0 among those with VF varied substantially (from 38 to 66%). Odds ratios (OR) for the association between LSBMD Z-score and VF were similar regardless of database (OR = 1.92, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.44, 2.56 to OR = 2.70, 95% CI: 1.70, 4.28). AUC and NRI ranged from 0.71 to 0.75 and −0.15 to 0.07 respectively.

Conclusions

Although the use of a LSBMD Z-score threshold as part of the definition of osteoporosis in a child with VF does not appear valid, the study of relationships between BMD and VF is valid regardless of the BMD database that is used.

Key Terms: Bone mineral density Z-scores, Prevalent vertebral fractures, Pediatric reference databases

Introduction

Children with a variety of chronic conditions are at risk for bone fragility and reductions in bone mineral density (BMD) due to osteoporosis, resulting either from the underlying conditions (such as leukemia, inflammatory conditions, and disorders which impede ambulation), or their treatment (for example, glucocorticoid therapy) (1–5). Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the most widely-used technique for the evaluation of BMD in children at risk for fractures, given the rapidity of scan acquisition, minimal radiation dose, the excellent precision and accuracy of the measurement, and broad availability. Interest in the clinical utility of DXA-based BMD measurement in children has heightened over recent years, because a growing number of pediatric studies have shown a clear relationship between low BMD and the risk of vertebral (6–8) and non-vertebral (9) fractures. As a result, the optimal use of DXA-based BMD to identify which children are in need of bone health monitoring is an ongoing point of focus for pediatric bone health care providers, with the ultimate goals being to predict individuals at risk of overt bone fragility and to intervene to prevent fractures.

One of the challenges facing clinicians in the use of DXA for assessing BMD in children is choosing the normative database that will be used to convert raw BMD scores to gender-and age-specific Z-scores. Over a dozen published normative databases are available for children on different DXA machines, with Hologic-based studies confirming that Z-scores vary significantly in children depending upon the normative reference database that is used to generate the Z-scores (10, 11). This issue is particularly relevant given that the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) pediatric osteoporosis definition includes a BMD threshold of −2.0 standard deviations (SD) or lower along with a clinically significant fracture history; recently, the ISCD has proposed that the exception to this is the presence of a low trauma vertebral fracture (VF), in which case the BMD threshold criteria do not apply (12). The use of the BMD Z-score to define osteoporosis in children raises the importance of understanding the clinical significance of the BMD Z-score variability generated by different normative databases and the relationship between Z-scores and the risk of fragility fractures.

We have previously shown in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) that 16% had prevalent VF around the time of diagnosis, and that every 1.0 standard deviation reduction in lumbar spine bone mineral density (LSBMD) Z-score was associated with 80% increased odds of VF at that time-point (6). We further showed that 16% of children had incident (i.e. new) VF at 12 months following chemotherapy initiation and that LSBMD Z-score predicted incident VF, with 40% increased likelihood of a new VF at 12 months for every 1 SD reduction in LSBMD Z-score at diagnosis (7).

It is important to note that these observations are based on the use of a specific LSBMD reference database to generate the Z-scores (6, 7). Because it has been previously shown (using Hologic instruments) that LSBMD Z-scores vary considerably depending on the normative database that is used (10, 11), we sought to more fully understand the clinical and research implications of the disparities in Z-scores generated by different BMD reference databases, through study of the relationship between LSBMD Z-scores and a key clinical endpoint in the pediatric chronic illness population, ie VF. Specifically, our goals were to: (1) assess the magnitude of the disparities in LSBMD Z-scores generated by different published normative references using both Hologic and Lunar instruments, and (2) evaluate whether the relationship between LSBMD Z-scores and VF varies depending on the LSBMD reference databases used to generate the Z-scores.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects and clinical data

Patients were recruited through pediatric oncology clinics in 10 children’s hospitals across Canada as part of the STeroid-associated Osteoporosis in the Pediatric Population (STOPP) research program (6, 7, 13). The study was approved by the Ethics Board in each institution and informed consent/assent was obtained, as appropriate. Children from 1 month to 17 years of age with ALL were enrolled from 2005 to 2007 with the baseline bone health assessment targeted within 30 days of glucocorticoid therapy initiation (median 20 days; interquartile range (IQR) 11 to 26 days). Among the 186 children enrolled in the study, 108 (58%) were boys and 140 (75%) were Caucasian. The ethnicities for the other 25% of the cohort were as follows: Native/Aboriginal people of North America (North American Indian, Métis, Inuit/Eskimo) (7%), South Asian (e.g., East Indian, Pakistani, Punjabi, Sri Lankan) (5%), Black (4%) and other (9%).

Standard demographic data including age, gender, and ethnicity were recorded (6). Children were treated according to the Children’s Oncology Group (6) (nine sites) or the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (one site) protocols. A comprehensive clinical description of this cohort has been published in two reports elsewhere (6, 7).

BMD (g/cm2) was measured in the anterior-posterior projection at the LS (L1 to L4) by DXA using cross-calibrated Hologic (Hologic, Bedford, MA) or Lunar Prodigy (GE Lunar Corporation, Madison, WI) systems to generate an areal LSBMD raw value. Details on Hologic and Lunar machine cross-calibration methodology have been described in previous reports (6, 7). All scans were analyzed centrally by one technologist using Hologic QDR (version 12.0) software.

Lateral thoracolumbar spine radiographs were scored independently by two pediatric radiologists according to the modified Genant semi-quantitative method (14) and a third radiologist adjudicated discrepancies. Vertebral bodies were graded according to the extent of the difference in height ratios from 100% when the anterior vertebral height was compared to the posterior height, the middle height to the posterior height, and the posterior height to the posterior height of adjacent vertebral bodies, with the following grade definitions: grade 0 (normal), 20% or less; grade 1 (mild), more than 20% to 25%; grade 2 (moderate), more than 25% to 40%; grade 3 (severe), more than 40%. Grade 1 or higher scores were considered to represent prevalent VF.

Pediatric reference data for generation of LSBMD Z-scores

A literature search was performed for pediatric LSBMD reference data that had been generated utilizing either Hologic or Lunar machines. These two machines were chosen because they are currently used across Canada and are the most commonly employed machines as reported in the pediatric literature. Normative reference databases that satisfied the following criteria were included in this study: (1) comprised of primarily Caucasian children because this was the composition of our cohort; (2) reference data that spanned a minimum age range of 5 years to less than 18 years or reference data for infants and toddlers (0 to 3 years); (3) sufficient methodological detail to permit calculation of age-and gender-specific LSBMD Z-scores; and (4) published in English. In addition, the Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) database, an unpublished database generated by the Hologic manufacturer, was also included in this study given its frequent use in clinical practice. In some cases, related databases were combined in order to generate a single database that spanned the age relevant to this pediatric ALL cohort (0 to 18 years).

LSBMD Z-score calculations

LSBMD Z-scores (for either L1 to L4 or L2 to L4, depending upon the parameter that was given by the normative reference database) were calculated using the selected published normative reference databases. The databases provided either “LMS” parameters (the power in the Box-Cox transformation (L), the median (M), the generalized coefficient of variation (S)), mean and standard deviation (M/SD) parameters, or gender-and age-specific formulae. Linear interpolation was applied to determine Z-scores for ages that were intermediate to age-related values provided in the normative reference databases. Ethnicity was taken into account for the LSBMD Z-score calculation when race-specific reference databases were available. Specifically, black children were analyzed on black reference data where available, and caucasian/non-black reference data were applied to Caucasian children. For the other ethnicities in this cohort, Caucasian/non-black reference data were applied to generate the LSBMD Z-scores due to lack of race-specific data.

Based on the age ranges available in the various normative reference databases, we defined six age groups for comparison of LSBMD Z-scores:

0 to 18 years (N = 186; 108 (58%) male; mean±SD age 6.6±4.0 years; 29 (16%) with VF)

0 to 5 years (n = 86; 53 (62%) male; age 3.3±0.9 years; 10 (12%) with fractures)

3 to 18 years (n = 153; 87 (57%) male; age 7.5±3.9 years; 26 (17%) with fractures)

5 to 18 years (n = 100; 56 (56%) male; age 9.4±3.5 years; 19 (19%) with fractures)

8 to 16 years (n = 51; 26 (51%) male; age 11.8±2.1 years; 10 (20%) with fractures), and

9 to 14 years (n = 37; 19 (51%) male; age 11.7±1.5 years; 7 (19%) with fractures).

Height Z-score-adjusted LSBMD Z-scores for children in the groups aged 5 to 18 years, 8 to 16 years and 9 to 14 years were also calculated, according to the method and reference data provided by Zemel et al. (16). The height adjustment was limited to these three different age ranges, because this was the age range available in the Zemel publication. Note that the original reference data published by Zemel et al. (16) was subsequently revised using updated software (17); this revised data was used to calculate the height Z-score-adjusted LSBMD Z-scores in the current report (17).

Statistical analysis

LSBMD Z-scores generated by various reference databases were reported as means and SD, and were compared using the Friedman test. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between LSBMD Z-scores generated using any pair of normative reference databases were calculated. Based on the cut-off threshold of −2, LSBMD Z-scores were categorized as low (≤−2) or normal (> −2) (12). A logistic regression model with VF as the outcome and LSBMD Z-score as the continuous risk factor was developed for each normative reference database. The model was adjusted for height and weight Z-scores when LSBMD Z-score was used in the model. The model was adjusted for weight Z-score only, when the height-adjusted LSBMD Z-score was used.

The odds ratios (OR) expressed the risk of VF for every 1 SD decrease in LSBMD Z-score. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), which measures how well LSBMD Z-scores can distinguish between children with and without VF, was determined. Cochran’s Q test (18) was conducted to assess the heterogeneity/variation in the OR and AUC within each age group across different normative reference databases. Continuous net reclassification improvement (NRI) (19) was calculated to assess the improvement in prediction of VF risk for every 1 SD decrease in LSBMD Z-score gained by using any other normative reference database in comparison to Hologic version 12.3 (chosen as the reference because this is the normative database used in the STOPP study) (20). Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, 2011). Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Results

Vertebral fractures

There were a total of 75 VF (53 thoracic, 22 lumbar) in 29/186 patients (16%), as previously described (6). Of the children with VF 48% had mild fractures as the worst grade, and 52% had moderate or severe VF. Additional details on the distribution of VF that were found in this cohort of children with ALL around the time of diagnosis have been previously published (6). There was no significant difference in the mean (SD) spine areal BMD raw scores (after cross-calibration) for those children with lumbar fractures (N=12) when the fractured vertebrae were included in the L1 to L4 BMD results (0.43 g/cm2 (0.14)) compared with when the fractured vertebrae were excluded (0.44 g/cm2 (0.13), p = 0.75 according to an independent two-sample t-test).

Correlations among LSBMD Z-scores derived on different normative reference databases

Our literature search yielded 15 databases that met the criteria outlined in the methods section. Table 1 shows the age ranges encompassed by each of these reference data, the nationalities of the children, and the parameters/calculations used for Z-score generation. Two additional normative reference databases encompassing the full pediatric age range (0 to 18 years) were constructed by combining reference data from different sources. The first was compiled by combining the Hologic Apex 3.1 database (15) with the published Hologic data from Kalkwarf et al (21). The second was constructed by combining the published Hologic data from Zemel et al (16) with those from Kalkwarf et al (21). These databases were combined to allow evaluation of the entire study population, given the similarity in methodological approaches between the two databases and the paucity of published databases covering the age range of our cohort.

Table 1.

Published Pediatric LSBMD Normative Reference Databases

| Reference | Manufacturer and machine | Software | Country, Year | Age range (years) | Number of subjects (female/male) | Study design# | Skeleta l site | Format$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hologic 12.3 (20) | Hologic | 12.3 | NA | 1–18 | NA | NA | L1-4 | M/SD |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) | Hologic | 3.1 | NA | 3–85 | NA | NA | L1-4 | LMS |

| Zemel 2011 (16) | Hologic QDR 4500A, QDR 4500W, Delphi A, Apex models | 11.1–12.7 | USA | 5–23 | 2014 (992/1022) | MP | L1-4 | LMS |

| Kalkwarf 2013 (21) | Hologic Discovery A | 12.7 | USA | 0–3 | 307 (149/158) | SX | L1-4 | LMS |

| Lunar (BMDCS) 2010 (27) | Lunar DPX, DPX-L, Prodigy | Argentina, Australia, Northern Europe | 7–16 | 2510 (1354/1156) | MP | L1-4 | M/SD | |

| Lunar (USA) 2010 (27) | Lunar DPX, DPX-L, Prodigy | USA | 5–19 | 675(420/255) | MP | L1-4 | M/SD | |

| Bachrach 1999 (22) | Hologic QDR 1000W | 6.10 | USA 1992–1996 | 8.8–25.9 | 423 (230/193) | SP | L2-4 | M/SD |

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | Lunar DPX-L | 3.4 and 3.5 | Spain 1993 | 0.25 –21 | 471 (215/256) | SP | L2-4 | M/SD |

| Faulkner 1996 (28) | Hologic QDR 2000 | 4.42A | Canada 1993–1996 | 8–17 | 234 (124/110) | SP | L1-4 | M/SD |

| Fonseca 2001 (32) | Lunar DPX | Brazil 1995–1998 | 6–14 | 255 (135/120) | SP | L2-4 | M/SD | |

| Kalkwarf 2007 (33) | Hologic QDR 4500A, QDR 4500W, Delphi A | 11.1–12.3 | USA 2002–2003 | Girls: 6–15 Boys: 6–16 | 1554 (793/761) | MP | L1-4 | LMS |

| Kelly 2005 (34) | Hologic QDR 4500A, Delphi A | USA 2005 | 3–20 | 1444 (942/502) | MX | L1-5 | M/SD | |

| Pludowski 2005 (26) | Lunar DPX-L | Poland | 5–18 | 562 (278/284) | SP | L2-4 | M/SD | |

| van der Sluis 2002 (25) | Lunar DPX-L/PED | Netherlands 1994–1995, 1998–1999 | 4–20 | 444 (256/188) 198 (114/84) | SP | L2-4 | M/SD | |

| Webber 2007 (23) | Hologic QDR 4500A, Discovery A | 8.26, 12.3 | Canada 2007 | 3–18 | 179 (91/88) | SP | L1-4 | Formula |

Note:

P: prospective design; X: cross-sectional design; S: single-center study; M: multicenter study.

LMS: Power in the Box-Cox transformation (L), median (M), and generalized coefficient of variation (S). When LMS are provided, Z-score = [(X/M)L-1]/LS, where X is the raw BMD score. M/SD: mean (M) and standard deviation (SD). When M/SD are provided, Z-score = (X–M)/SD, where X is the raw BMD score.

Correlations of LSBMD Z-scores generated on each pair of normative reference databases within each age group ranged from r = 0.90 to 0.99 for the age group 0 to 18 years, 0.95 to 0.99 for the age group 3 to 18 years, 0.90 to 0.99 for the age group 5 to 18 years, 0.88 to 0.99 for the age group 8 to 16 years, 0.85 to 0.99 for the age group 9 to 14 years, and r = 0.92 for the 0 to 5 years group. Most coefficients (94%) were above 0.90. The lowest were 0.85 between the Hologic 12.3 (20) and Bachrach 1999 (22) in the age group 9 to 14 years. The high correlation coefficients indicated a strong linear correlation between the LSBMD Z-scores generated using different normative reference databases.

The mean LSBMD Z-scores generated by the normative reference databases varied from −2.0 to −0.5 for the age group 0 to 18 years, −2.0 to −1.4 for the age group 0 to 5 years, −2.1 to −0.3 for the age group 3 to 18 years, −2.0 to −0.1 for the age group 5 to 18 years, −1.9 to 0.1 for the age group 8 to 16 years, and −2.0 to 0 for the age group 9 to 14 years (Table 2). The mean LSBMD Z-scores were < 0 for all databases, with the exception of the Webber database (23) (used for age group 8 to 16 years and age group 9 to 14 years). The Del Rio (24) normative reference database produced the lowest mean Z-scores within each age group. Overall, the mean LSBMD Z-scores were significantly different within each age group for the various reference databases (p < 0.001). The maximum disparity in the mean LSBMD Z-score was 2.0 SD (between the Webber (23) and the Del Rio databases (24) for the age groups 8 to 16 years and 9 to 14 years).

Table 2.

Proportion of Study Subjects Assigned LSBMD Z-scores ≤ −2

| Age Group (proportion of children with fractures) | Reference database | LSBMD Z-score (mean (SD§)) | LSBMD Z-scores ≤−2 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–18 years (29/186) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | −1.2 (1.3) | 46 (25) |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15)+Kalkwarf 2013 (21) | −0.5 (1.5) | 28 (15) | |

| Zemel 2011(16)+Kalkwarf 2013 (21) | −0.6 (1.6) | 31 (17) | |

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | −2.0 (1.1) | 90 (48) | |

|

| |||

| 0–5 years (10/86) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | −1.4 (1.2) | 22 (26) |

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | −2.0 (1.0) | 37 (43) | |

|

| |||

| 3–18 years (26/153) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | −1.2 (1.3) | 39 (25) |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) | −0.5 (1.5) | 21 (14) | |

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | −2.1 (1.2) | 81 (53) | |

| Kelly 2005 (34) | −0.6 (1.4) | 21 (14) | |

| Webber 2007 (23) | −0.3 (1.3) | 15 (10) | |

|

| |||

| 5–18 years* (19/100) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | −1.0 (1.3) | 24 (24) |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) | −0.3 (1.4) | 9 (9) | |

| Zemel 2011 (16) | −0.3 (1.4) | 9 (9) | |

| Lunar (USA) 2010 (27) | −0.9 (1.2) | 16 (16) | |

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | −2.0 (1.2) | 53 (53) | |

| Kelly 2005 (34) | −0.4 (1.3) | 9 (9) | |

| Pludowski 2005 (26) | −1.4 (1.1) | 29 (29) | |

| van der Sluis 2002 (25) | −1.9 (1.2) | 50 (50) | |

| Webber 2007 (23) | −0.1 (1.3) | 7 (7) | |

|

| |||

| 8–16 years* (10/51) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | −0.8 (1.4) | 9 (18) |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) | −0.1 (1.3) | 3 (6) | |

| Zemel 2011 (16) | −0.1 (1.2) | 3 (6) | |

| Lunar (BMDCS) 2010 (27) | −0.4 (1.3) | 5 (10) | |

| Lunar (USA) 2010 (27) | −0.6 (1.2) | 5 (10) | |

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | −1.9 (1.3) | 25 (49) | |

| Faulkner 1996 (28) | −0.2 (1.5) | 4 (8) | |

| Kalkwarf 2007 (33) | −0.1 (1.3) | 4 (8) | |

| Kelly 2005 (34) | −0.3 (1.2) | 3 (6) | |

| Pludowski 2005 (26) | −1.4 (1.2) | 14 (27) | |

| van der Sluis 2002 (25) | −1.6 (1.1) | 17 (33) | |

| Webber 2007 (23) | 0.1 (1.3) | 2 (4) | |

|

| |||

| 9–14 years* (7/37) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | −0.9 (1.3) | 8 (22) |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) | −0.2 (1.2) | 2 (5) | |

| Zemel 2011 (16) | −0.2 (1.2) | 2 (5) | |

| Lunar (BMDCS) 2010 (27) | −0.5 (1.2) | 4 (11) | |

| Lunar (USA) 2010 (27) | −0.7 (1.1) | 4 (11) | |

| Bachrach 1999 (22) | −1.2 (1.1) | 9 (24) | |

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | −2.0 (1.1) | 20 (54) | |

| Faulkner 1996 (28) | −0.3 (1.5) | 3 (8) | |

| Fonseca 2001 (32) | −1.7 (1.3) | 14 (38) | |

| Kalkwarf 2007 (33) | −0.2 (1.2) | 3 (8) | |

| Kelly 2005 (34) | −0.4 (1.1) | 2 (5) | |

| Pludowski 2005 (26) | −1.5 (1.1) | 11 (30) | |

| van der Sluis 2002 (25) | −1.7 (1.0) | 13 (35) | |

| Webber 2007 (23) | 0.0 (1.3) | 1 (3) | |

Note:

SD = standard deviation

Summary statistics are calculated using height Z-score-adjusted LSBMD Z-score for this age group (based on the ages available for this calculation according to Zemel et al (16)

Proportion of children assigned LSBMD Z-scores ≤ −2 SD

Overall, the numbers and percentages of children with LSBMD Z-scores at or below −2.0 SD differed substantially depending upon the database used for the Z-score calculation (Table 2). Among the entire cohort of 186 children with ALL from 0 to 18 years of age, the discrepancy between databases ranged from 15% of children ≤ −2.0 SD for the Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) + Kalkwarf (21) combined database, to 48% of children for the Del Rio database (24). Among the normative reference databases studying children 5 to 18 years of age, the Del Rio database (24) designated spine BMD Z-score at or below −2.0 in 53% of the study subjects compared with 7% on the Webber database (23).

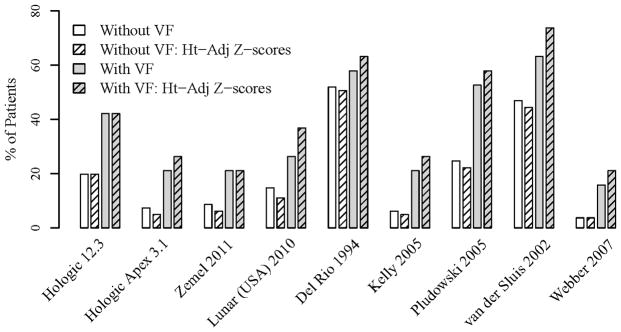

Among the 29 children with ALL from 0 to 18 years of age who had VF, the percentages of children with LSBMD Z-scores ≤ −2.0 SD on the various databases were as follows: 52% for the Hologic 12.3 database (20), 38% for the Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) and Kalkwarf (21) combined database, 38% for the Zemel (16) and Kalkwarf (21) combined database, and 66% for the Del Rio database (24). Among the 19 children in the 5 to 18 years of age group who had VF, the proportion with height-adjusted LSBMD Z-scores worse than −2 ranged from 21% for the Webber (23) and Zemel databases (16) to 74% for the van der Sluis database (25) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients aged 5 to 18 years with height-adjusted and non-adjusted LSBMD Z-score ≤ −2

Association between LSBMD Z-score and vertebral fracture

For the age group 0 to 18 years, OR for the association between LSBMD Z-score and VF were similar and ranged from 1.92 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.44, 2.56) to 2.70 (95% CI: 1.70, 4.28) per SD decrease in Z-score (Table 3); the non-significant p value from the Cochran’s Q test confirmed that these differences were statistically insignificant. These results also confirmed that lower LSBMD Z-scores were significantly associated with increased risk of VF. Results for other age groups showed similar patterns, i.e. similar OR for the relationship between LSBMD Z-scores and VF, regardless of the normative database used to generate the Z-scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationships between LSBMD Z-Score and Vertebral Fractures

| Age Group (proportion of children with fractures) | Reference database | Odds ratio$ (95% CI*) | p-value from Cochran’s Q test | AUC# (95% CI*) | p-value from Cochran’s Q test | NRI+ (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–18 years (29/186) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | 2.36 (1.58, 3.53) | 0.61 | 0.74 (0.63, 0.85) | 0.98 | Reference | |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) +Kalkwarf 2013 (21) | 2.05 (1.49, 2.82) | 0.73 (0.61, 0.84) | −0.06 (−0.45, 0.33) | 0.75 | |||

| Zemel 2011 (16) + Kalkwarf 2013 (21) | 1.92 (1.44, 2.56) | 0.71 (0.60, 0.83) | −0.15 (−0.54, 0.25) | 0.46 | |||

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | 2.70 (1.70, 4.28) | 0.75 (0.63, 0.86) | 0.07 (−0.32, 0.47) | 0.72 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 0–5 years (10/86) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | 11.36 (2.78, 46.40) | 0.98 | 0.95 (0.89, 1.00) | 0.61 | Reference | |

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | 11.66 (2.93, 46.38) | 0.92 (0.80, 1.00) | −0.67 (−1.31, −0.03) | 0.04 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 3–18 years (26/153) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | 2.22 (1.47, 3.35) | 0.99 | 0.73 (0.60, 0.85) | >0.99 | Reference | |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) | 2.08 (1.46, 2.97) | 0.72 (0.60, 0.84) | 0.29 (−0.13, 0.71) | 0.18 | |||

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | 2.40 (1.49, 3.86) | 0.72 (0.60, 0.85) | −0.15 (−0.56, 0.27) | 0.49 | |||

| Kelly 2005 (34) | 2.17 (1.49, 3.17) | 0.72 (0.60, 0.84) | 0.41 (0.00, 0.83) | 0.05 | |||

| Webber 2007 (23) | 2.23 (1.47, 3.39) | 0.71 (0.58, 0.83) | −0.02 (−0.44, 0.40) | 0.92 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 5–18 years§ (19/100) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | 1.66 (1.07, 2.60) | >0.99 | 0.67 (0.52, 0.82) | >0.99 | Reference | |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) | 1.69 (1.14, 2.52) | 0.68 (0.53, 0.83) | 0.28 (−0.21, 0.77) | 0.27 | |||

| Zemel 2011 (16) | 1.63 (1.10, 2.42) | 0.67 (0.52, 0.82) | 0.10 (−0.39, 0.59) | 0.69 | |||

| Lunar (USA) 2010 (27) | 1.71 (1.08, 2.73) | 0.67 (0.52, 0.82) | −0.10 (−0.59, 0.38) | 0.69 | |||

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | 1.68 (1.04, 2.69) | 0.67 (0.51, 0.82) | 0.11 (−0.38, 0.61) | 0.65 | |||

| Kelly 2005 (34) | 1.68 (1.10, 2.55) | 0.68 (0.52, 0.83) | 0.13 (−0.36, 0.62) | 0.61 | |||

| Pludowski 2005 (26) | 1.89 (1.11, 3.21) | 0.68 (0.52, 0.84) | 0.24 (−0.25, 0.74) | 0.33 | |||

| van der Sluis 2002 (25) | 1.59 (1.01, 2.50) | 0.66 (0.52, 0.80) | −0.37 (−0.86, 0.11) | 0.13 | |||

| Webber 2007 (23) | 1.65 (1.07, 2.55) | 0.66 (0.51, 0.81) | 0.21 (−0.28, 0.71) | 0.40 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 8–16 years§ (10/51) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | 2.31 (1.16, 4.59) | >0.99 | 0.76 (0.57, 0.95) | >0.99 | Reference | |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) | 2.52 (1.25, 5.08) | 0.81 (0.65, 0.98) | 0.67 (0.03, 1.31) | 0.04 | |||

| Zemel 2011 (16) | 2.45 (1.22, 4.92) | 0.79 (0.62, 0.96) | 0.42 (−0.26, 1.10) | 0.22 | |||

| Lunar (BMDCS) 2010 (27) | 2.63 (1.27, 5.44) | 0.80 (0.63, 0.98) | 0.47 (−0.21, 1.14) | 0.17 | |||

| Lunar (USA) 2010 (27) | 2.78 (1.25, 6.19) | 0.80 (0.62, 0.98) | 0.57 (−0.07, 1.21) | 0.08 | |||

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | 2.05 (1.05, 3.99) | 0.76 (0.55, 0.96) | −0.57 (−1.21, 0.07) | 0.08 | |||

| Faulkner 1996 (28) | 2.09 (1.14, 3.83) | 0.76 (0.55, 0.96) | 0.02 (−0.67, 0.72) | 0.94 | |||

| Kalkwarf 2007 (33) | 2.41 (1.21, 4.79) | 0.79 (0.62, 0.96) | 0.42 (−0.26, 1.10) | 0.22 | |||

| Kelly 2005 (34) | 2.56 (1.24, 5.31) | 0.80 (0.62, 0.97) | 0.52 (−0.12, 1.17) | 0.11 | |||

| Pludowski 2005 (26) | 2.58 (1.25, 5.34) | 0.78 (0.58, 0.98) | 0.77 (0.19, 1.35) | 0.01 | |||

| van der Sluis 2002 (25) | 2.87 (1.25, 6.56) | 0.81 (0.62, 1.00) | 0.47 (−0.17, 1.12) | 0.15 | |||

| Webber 2007 (23) | 2.09 (1.10, 4.00) | 0.76 (0.58, 0.95) | −0.07 (−0.76, 0.62) | 0.84 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 9–14 years§ (7/37) | Hologic 12.3 (20) | 4.27 (1.36, 13.44) | 0.97 | 0.85 (0.66, 1.00) | >0.99 | Reference | |

| Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) | 6.00 (1.46, 24.63) | 0.90 (0.73, 1.00) | 0.61 (−0.19, 1.41) | 0.13 | |||

| Zemel 2011 (16) | 5.36 (1.44, 19.94) | 0.88 (0.73, 1.00) | 0.90 (0.15, 1.64) | 0.02 | |||

| Lunar (BMDCS) 2010 (27) | 6.67 (1.54, 28.91) | 0.89 (0.72, 1.00) | 0.68 (−0.12, 1.47) | 0.09 | |||

| Lunar (USA) 2010 (27) | 11.22 (1.77, 71.28) | 0.89 (0.73, 1.00) | 0.81 (0.03, 1.59) | 0.04 | |||

| Bachrach 1999 (22) | 18.06 (1.82, 178.99) | 0.94 (0.86, 1.00) | 1.18 (0.57, 1.79) | <0.01 | |||

| Del Rio 1994 (24) | 6.44 (1.58, 26.35) | 0.89 (0.76, 1.00) | 0.41 (−0.40, 1.22) | 0.32 | |||

| Faulkner 1996 (28) | 2.95 (1.13, 7.69) | 0.82 (0.60, 1.00) | −0.98(−1.60, −0.36) | <0.01 | |||

| Fonseca 2001 (32) | 4.05 (1.38, 11.90) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.00) | −0.21 (−1.03, 0.61) | 0.61 | |||

| Kalkwarf 2007 (33) | 5.29 (1.42, 19.68) | 0.87 (0.72, 1.00) | 0.61 (−0.19, 1.41) | 0.13 | |||

| Kelly 2005 (34) | 7.14 (1.57, 32.44) | 0.89 (0.74, 1.00) | 0.32 (−0.47, 1.12) | 0.43 | |||

| Pludowski 2005 (26) | 5.15 (1.50, 17.68) | 0.87 (0.70, 1.00) | 0.56 (−0.20, 1.32) | 0.15 | |||

| van der Sluis 2002 (25) | 19.02 (1.85, 195.78) | 0.91 (0.79, 1.00) | 1.67 (1.40, 1.93) | <0.01 | |||

| Webber 2007 (23) | 4.75 (1.30, 17.43) | 0.85 (0.68, 1.00) | −0.01 (−0.82, 0.81) | 0.98 | |||

Note:

CI = confidence interval

AUC = area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

NRI = net reclassification improvement

Odds ratio = odds per standard deviation decrease in lumbar spine bone mineral density Z-score

Statistical analyses are based on the height Z-score-adjusted LSBMD Z-scores for this age group.

The predictive accuracy of LSBMD Z-scores for VF was tightly clustered across different normative reference databases for each age group (Table 3). For example, the AUC for the age group 0 to 18 years ranged from 0.71 (95% CI: 0.60–0.83) to 0.75 (95% CI: 0.63–0.86). Likewise, similar AUC results were present in each age group, confirmed by the non-significant p values from the Cochran’s Q test. Similarly, there was no significant improvement in NRI by any normative reference database compared to Hologic 12.3 (20) except for Del Rio (24) reference database for the age group 0 to 5 years, Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) and Pludowski (26) reference databases for the age group 8 to 16 years, and Zemel (16), Lunar (USA) (27), Bachrach (22), Faulkner (28) and van der Sluis (25) reference databases for the age group 9 to 14 years. These exceptions in these age groups may due to: (1) the inflated differences in predictive accuracies associated with the NRIs; and/or (2) unstable estimates arising from the logistic regression models, given that the overall sample size and the number of children with VF in these two age groups were small. For the age group 0 to 18 years (which spans the age range in the entire leukemia STOPP cohort), the NRI were similar compared to Hologic 12.3 (20) for all of the studied reference databases, ranging from −0.15 (95% CI: −0.54, 0.25; p = 0.46) to 0.07 (95% CI: −0.32, 0.47; p = 0.72).

Discussion

We found that in our cohort of children with an acute critical illness and the potential for significant bone morbidity, the mean Z-scores varied substantially with maximum disparity of 1.5, 0.6, 1.8, 1.9, 2.0 and 2.0 SD for age groups 0 to 18, 0 to 5, 3 to 18, 5 to 18, 8 to 16, and 9 to 14 years respectively (Table 2). Not surprisingly, the LSBMD Z-scores arising from the largest normative reference databases (i.e. those on more than 600 children, which include normative reference databases generated by the machine manufacturers) gave mid-range results overall and were more similar to each other, while the greatest disparities arose from normative databases generated on small numbers of children. This observed variability likely results from a host of factors, including differences in the brand, model, and software used for LSBMD acquisition, as well as inherent differences in the sample populations upon which the normative databases were derived (arising from genetic and/or lifestyle differences).

The consequences of a single absolute BMD value generating markedly different Z-scores depending on the normative reference database used are important in two areas: (1) clinical practice, where the Z-score has traditionally been part of assessing a child’s skeletal status and defining the presence or absence of osteoporosis; and (2) research studies, which attempt to define the relationship between BMD and other clinical risk factors and fracture outcomes.

For the clinician evaluating bone health in a child with or at risk for a VF (i.e. at the individual patient level), the use of LSBMD Z-scores is problematic given the disparate Z-scores that are generated by the various normative reference databases. In our study population, the proportion falling below the traditionally diagnostic BMD threshold of ≤ −2 (who would be categorized as below the expected range for age), varied markedly for children 0 to 18 years of age, from 15% for the Hologic Apex 3.1 (15) and Kalkwarf (21) combined database, to 48% using the Del Rio (24) database.

The inaugural (2008) ISCD criteria for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in children included a BMD Z-score ≤ −2 as part of the definition (29). However, updated guidelines published in 2014 state that the presence of one or more low trauma VF is sufficient to diagnose osteoporosis, regardless of BMD findings (12). Our results provide concrete evidence to support this new definition, because we have shown that children with ALL and VF often have spine BMD Z-scores above −2.0 SD (although with variability, depending upon the normative database used to generate the Z-scores). Specifically, among the 29 children with leukemia in our cohort with VF, the proportion assigned a LSBMD Z-score better than −2 SD (i.e. in the face of overt bone fragility) ranged from 38% to 66% depending on the normative database that was used.

At the same time, the new (2014) ISCD criteria have retained a BMD Z-score threshold at or below −2 as part of the definition of osteoporosis in children who have clinically significant fractures other than at the spine (i.e. low-trauma, non-VF) (12). As part of this scenario, there is a caveat in the new ISCD guidelines to the effect that a BMD or bone mineral content Z-score ≤ −2.0 in a child with a non-VF does not preclude skeletal fragility and increased fracture risk. This proviso emphasizes the importance of the fracture history in the non-VF setting. Interestingly, Henderson (9) showed in children with cerebral palsy, that for every 1 SD reduction in distal femur BMD by DXA, there was a 15% increased non-VF risk. In line with our results, Henderson et al. (9) also reported that while the prevalence of non-VF increased with lower distal femur Z-scores, some children nevertheless had non-VF despite distal femur BMD Z-scores > −1 SD. These data in children with cerebral palsy also support an osteoporosis definition that emphasizes the fracture history in those with non-VF.

Ultimately, what may bypass these issues is a standardized LSBMD normative reference database generated using a representative sample of children who are scanned on both Hologic and Lunar machines. When such a database is available, studies could then be done to test clinically relevant Z-score thresholds, which might differ from the arbitrary value of −2.0 that has been used to this point. The incorporation of other risk factors beyond BMD into fracture prediction models (such as has been done for adults, FRAX(30)) will also likely strengthen the ability to predict VF and non-VF in children.

There are a number of strengths and limitations to this study. This report is novel in its exploration of the disparity in BMD Z-scores generated by different normative databases, first by including both Hologic and Lunar machines, and secondly by studying the relationship between LSBMD Z-scores and VF depending on the normative database that is used to generate the Z-scores. In addition, this report provides data on a cohort that is representative of children who are frequently referred for a bone health evaluation, and so places the issues facing the clinician into sharp focus. Furthermore, calculation of the AUC and NRI provides the clinician with the opportunity to assess the predictive accuracy of LSBMD Z-scores for VF children depending on the normative database that is chosen for implementation in the clinic. A limitation of this study is that only the relationship between LSBMD and VF was explored, and not the relationship between BMD and other fracture types. Another is that only spine BMD was assessed, and not BMD at other skeletal sites. A third limitation is that our study subjects all have ALL; additional studies will be needed to determine whether similar relationships exist in other disease types. As well, we acknowledge that the differences in machine technology (i.e. pencil versus fan beam scan acquisition for the various reference databases) may have influenced the accuracy of the data. At the same time, Faulkner et al. showed that fan versus pencil beam technology did not lead to clinically significant differences (31).

In summary, we observed marked disparity in LSBMD Z-scores depending on the normative database that was used, and that children with VF frequently had LSBMD Z-scores > −2 SD. On the other hand, the relationship between LSBMD Z-scores and VF was consistent among the different normative reference databases. These results suggest that although the use of a LSBMD Z-score threshold as part of the definition of osteoporosis in a child with VF does not appear valid, the study of relationships between BMD and VF remains valid regardless of the BMD database that is used.

Acknowledgments

This study was primarily funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (FRN 64285). Additional funding for this work has been provided to Dr. Leanne Ward by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research New Investigator Program, the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Career Enhancement Program, a University of Ottawa Research Chair Award and the CHEO Departments of Pediatrics and Surgery. This work was also supported by the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute and the University of Alberta Women and Children’s Health Research Institute.

The Canadian STOPP Consortium would like to thank the children and their families who participated in the study and without whom the STOPP study would not have been possible.

We also thank the research Associates who managed the study at the co-ordinating center (the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Ottawa, Ontario): Elizabeth Sykes (STOPP Project Manager), Maya Scharke (STOPP Data Analyst and Database Manager), Monica Tomiak (Statistical Analyses), Victor Konji (STOPP Publications and Presentations Committee Liaison), Steve Anderson (Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pediatric Bone Health Program Research Manager), Catherine Riddell (STOPP National Study Monitor); Research Associates who took care of the patients from the following institutions: Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, Alberta: Eileen Pyra; British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver British Columbia: Terry Viczko, Sandy Hwang, Angelyne Sarmiento; Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario: Heather Cosgrove, Josie MacLennan, Catherine Riddell; Children’s Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario: Vinolia ArthurHayward, Leila MacBean, Mala Ramu; McMaster Children’s Hospital, Hamilton, Ontario: Susan Docherty-Skippen; IWK Health Center, Halifax, Nova Scotia: Cindy Campbell, Aleasha Warner; Montréal Children’s Hospital, Montréal, Québec: Valérie Gagné, Diane Laforte, Maritza Laprise; Ste. Justine Hospital, Montréal, Québec: Claude Belleville, Natacha GaulinMarion; Stollery Children’s Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta: Ronda Blasco, Germaine McInnes, Amanda Mullins; Toronto Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario: Alexandra Airhart, Michele Petrovic, Nicole Sarvaria; Winnipeg Children’s Hospital, Winnipeg, Manitoba: Dan Catte, Erika Bloomfield, Jeannine Schellenberg. The Research Nurses, Support Staff and all the STOPP collaborators from the various Divisions of Nephrology, Oncology, Rheumatology and Radiology who have contributed to the care of the children enrolled in the study.

Abbreviations

- BMD

Bone mineral density

- LS

Lumbar spine

- DXA

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- ISCD

International Society for Clinical Densitometry

- VF

Vertebral fracture

- ALL

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- IQR

Inter-quartile range

- M

Mean or Median

- SD

Standard deviation

- L

The power in the Box-Cox transformation

- S

The generalized coefficient of variation

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- AUC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- NRI

Net reclassification improvement

The Canadian STeroid-associated Osteoporosis in the Pediatric Population (STOPP) Consortium (a pan-Canadian, pediatric bone health working group)

Co-ordinating Center

Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario: Leanne M. Ward#,*,§ (Study Principal Investigator), Janusz Feber*,§ (Nephrology), Jacqueline Halton*,§ (Oncology), Roman Jurencak (Rheumatology), MaryAnn Matzinger (Radiology, Central Radiograph Analyses), Johannes Roth (Rheumatology), Nazih Shenouda§ (Radiology, Central Radiograph Analyses), Jinhui Ma (Research Methods and Statistics)

Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa Methods Centre Ottawa, Ontario: David Moher*,§ (Research Methods), Monica Taljaard (Research Methods and Statistics)

Participating Centers

Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, Alberta: Josephine Ho (Site Principal Investigator, from July 2013 to current), David Stephure (Bone Health, Site Principal investigator until July, 2013), Reinhard Kloiber (Radiology), Victor Lewis (Oncology), Julian Midgley (Nephrology), Paivi Miettunen (Rheumatology)

British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia: David Cabral* (Site Principal Investigator), David B. Dix (Oncology), Kristin Houghton (Rheumatology), Helen R. Nadel (Radiology)

British Columbia Women’s Health Sciences Centre, and Dept. of Radiology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia: Brian C. Lentle§ (Radiology)

Brock University, Faculty of Applied Health Sciences, St. Catharines, Ontario: John Hay§ (Physical Activity Measurements)

Children’s Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario: Robert Stein (Site Principal Investigator), Elizabeth Cairney (Oncology), Cheril Clarson (Bone Health), Guido Filler (Nephrology)§, Joanne Grimmer (Nephrology), Scott McKillop (Radiology, from 2012 to current), Keith Sparrow (Radiology, until 2012)

IWK Health Center, Halifax, Nova Scotia: Elizabeth Cummings (Site Principal Investigator), Conrad Fernandez (Oncology), Adam M. Huber§ (Rheumatology), Bianca Lang*,§ (Rheumatology), Kathy O’Brien (Radiology)

McMaster Children’s Hospital, Hamilton, Ontario: Stephanie Atkinson*,§ (Site Principal Investigator), Steve Arora (Nephrology), Ronald Barr§ (Oncology), Craig Coblentz (Radiology), Peter B. Dent (Rheumatology), Maggie Larche (Rheumatology)

Montréal Children’s Hospital, Montréal, Québec: Anne Marie Sbrocchi (Site Principal Investigator, from 2013 to current), Celia Rodd§ (Site Principal Investigator, until 2013), Sharon Abish (Oncology), Lorraine Bell (Nephrology), Claire LeBlanc (Rheumatology), Rosie Scuccimarri (Rheumatology)

Shriners Hospital for Children, Montréal, Québec: Frank Rauch*,§ (Co-Chair, Publications and Presentations Committee and Ancillary Studies Committee)

Ste. Justine Hospital, Montréal, Québec: Nathalie Alos* (Site Principal Investigator), Josée Dubois (Radiology), Caroline Laverdière (Oncology), Véronique Phan (Nephrology), Claire Saint-Cyr (Rheumatology)

Stollery Children’s Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta: Robert Couch* (Site Principal Investigator), Janet Ellsworth (Rheumatology), Maury Pinsk (Nephrology), Jacob Jaremko and Kerry Siminoski§ (Radiology), Beverly Wilson (Oncology),

Toronto Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario: Ronald Grant* (Site Principal Investigator), Martin Charron (Radiology, until 2013), Diane Hebert (Nephrology)

Université de Sherbrooke, Department of family medicine, Sherbrooke, Québec: Isabelle Gaboury*,§ (Biostatistics)

Winnipeg Children’s Hospital, Winnipeg, Manitoba: Shayne Taback§ (Site Principal Investigator), Tom Blydt-Hansen (Nephrology), Sara Israels (Oncology), Kiem Oen (Rheumatology), Martin Reed (Radiology), Celia Rodd§ (Bone Health, from 2013 to current)

Footnotes

Principal Investigator;

Executive Committee Member;

Publications and Presentations Committee Member

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose

References

- 1.Kilpinen-Loisa P, Paasio T, Soiva M, Ritanen UM, Lautala P, Palmu P, Pihko H, Makitie O. Low bone mass in patients with motor disability: prevalence and risk factors in 59 Finnish children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:276–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King WM, Ruttencutter R, Nagaraja HN, Matkovic V, Landoll J, Hoyle C, Mendell JR, Kissel JT. Orthopedic outcomes of long-term daily corticosteroid treatment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2007;68:1607–1613. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260974.41514.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogler W, Wehl G, van Staa T, Meister B, Klein-Franke A, Kropshofer G. Incidence of skeletal complications during treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: comparison of fracture risk with the General Practice Research Database. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:21–27. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnham JM, Shults J, Weinstein R, Lewis JD, Leonard MB. Childhood onset arthritis is associated with an increased risk of fracture: a population based study using the General Practice Research Database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1074–1079. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.048835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodd C, Lang B, Ramsay T, Alos N, Huber AM, Cabral DA, Scuccimarri R, Miettunen PM, Roth J, Atkinson SA, Couch R, Cummings EA, Dent PB, Ellsworth J, Hay J, Houghton K, Jurencak R, Larche M, LeBlanc C, Oen K, Saint-Cyr C, Stein R, Stephure D, Taback S, Lentle B, Matzinger M, Shenouda N, Moher D, Rauch F, Siminoski K, Ward LM. Incident vertebral fractures among children with rheumatic disorders 12 months after glucocorticoid initiation: a national observational study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:122–131. doi: 10.1002/acr.20589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halton J, Gaboury I, Grant R, Alos N, Cummings EA, Matzinger M, Shenouda N, Lentle B, Abish S, Atkinson S, Cairney E, Dix D, Israels S, Stephure D, Wilson B, Hay J, Moher D, Rauch F, Siminoski K, Ward LM the Canadian STOPP Consortium. Advanced vertebral fracture among newly diagnosed children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of the Canadian Steroid-Associated Osteoporosis in the Pediatric Population (STOPP) research program. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1326–1334. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alos N, Grant RM, Ramsay T, Halton J, Cummings EA, Miettunen PM, Abish S, Atkinson S, Barr R, Cabral DA, Cairney E, Couch R, Dix DB, Fernandez CV, Hay J, Israels S, Laverdiere C, Lentle B, Lewis V, Matzinger M, Rodd C, Shenouda N, Stein R, Stephure D, Taback S, Wilson B, Williams K, Rauch F, Siminoski K, Ward LM. High incidence of vertebral fractures in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia 12 months after the initiation of therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2760–2767. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben Amor IM, Roughley P, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. Skeletal clinical characteristics of osteogenesis imperfecta caused by haploinsufficiency mutations in COL1A1. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:2001–2007. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson RC, Berglund LM, May R, Zemel BS, Grossberg RI, Johnson J, Plotkin H, Stevenson RD, Szalay E, Wong B, Kecskemethy HH, Harcke HT. The relationship between fractures and DXA measures of BMD in the distal femur of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:520–526. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.091007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonard MB, Propert KJ, Zemel BS, Stallings VA, Feldman HI. Discrepancies in pediatric bone mineral density reference data: potential for misdiagnosis of osteopenia. J Pediatr. 1999;135:182–188. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kocks J, Ward K, Mughal Z, Moncayo R, Adams J, Hogler W. Z-score comparability of bone mineral density reference databases for children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4652–4659. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bishop N, Arundel P, Clark E, Dimitri P, Farr J, Jones G, Makitie O, Munns CF, Shaw N. Fracture Prediction and the Definition of Osteoporosis in Children and Adolescents: The ISCD 2013 Pediatric Official Positions. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siminoski K, Lee KC, Jen H, Warshawski R, Matzinger MA, Shenouda N, Charron M, Coblentz C, Dubois J, Kloiber R, Nadel H, O’Brien K, Reed M, Sparrow K, Webber C, Lentle B, Ward LM. Anatomical distribution of vertebral fractures: comparison of pediatric and adult spines. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:1999–2008. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1837-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1137–1148. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hologic Inc. Hologic Apex 3.1 Normative Database. Summary of Hologic Reference Data – Apex 3.1. Hologic, Inc; 35 Crosby Drive, Bedford, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zemel BS, Kalkwarf HJ, Gilsanz V, Lappe JM, Oberfield S, Shepherd JA, Frederick MM, Huang X, Lu M, Mahboubi S, Hangartner T, Winer KK. Revised reference curves for bone mineral content and areal bone mineral density according to age and sex for black and non-black children: results of the bone mineral density in childhood study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3160–3169. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zemel BS, Kalkwarf HJ, Gilsanz V, Lappe JM, Oberfield S, Shepherd JA, Frederick MM, Huang X, Lu M, Mahboubi S, Hangartner T, Winer KK. Revised reference curves for bone mineral content and areal bone mineral density according to age and sex for black and non-black children: results of the bone mineral density in childhood study. [Accessed October 24, 2014];J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 96 doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1111. Supplemental data. Available at http://press.endocrine.org/doi/suppl/10.1210/jc.2011-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:110–129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leening MJ, Vedder MM, Witteman JC, Pencina MJ, Steyerberg EW. Net reclassification improvement: computation, interpretation, and controversies: a literature review and clinician’s guide. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:122–131. doi: 10.7326/M13-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonnick SL. Hologic 12.3. In: Bonnick SL, editor. Bone densitometry in clinical practice: application and interpretation. 2. New Jersey: Humana; 2004. pp. 483–492. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalkwarf HJ, Zemel BS, Yolton K, Heubi JE. Bone mineral content and density of the lumbar spine of infants and toddlers: influence of age, sex, race, growth, and human milk feeding. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:206–212. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachrach LK, Hastie T, Wang MC, Narasimhan B, Marcus R. Bone mineral acquisition in healthy Asian, Hispanic, black, and Caucasian youth: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4702–4712. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.12.6182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webber CE, Beaumont LF, Morrison J, Sala A, Barr RD. Age-predicted values for lumbar spine, proximal femur, and whole-body bone mineral density: results from a population of normal children aged 3 to 18 years. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2007;58:37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.del Rio L, Carrascosa A, Pons F, Gusinye M, Yeste D, Domenech FM. Bone mineral density of the lumbar spine in white Mediterranean Spanish children and adolescents: changes related to age, sex, and puberty. Pediatr Res. 1994;35:362–366. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199403000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Sluis IM, de Ridder MA, Boot AM, Krenning EP, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM. Reference data for bone density and body composition measured with dual energy x ray absorptiometry in white children and young adults. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:341–347. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.4.341. discussion 341–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pludowski P, Matusik H, Olszaniecka M, Lebiedowski M, Lorenc RS. Reference values for the indicators of skeletal and muscular status of healthy Polish children. J Clin Densitom. 2005;8:164–177. doi: 10.1385/jcd:8:2:164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lunar GE Healthcare. Lunar enCORE pediatric reference data supplement. Madison, WI: Lunar GE Healthcare Corporation; 2010. Lunar enCORE pediatric reference data supplement; revision 1 Nov-2010 LU44662; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faulkner RA, Bailey DA, Drinkwater DT, McKay HA, Arnold C, Wilkinson AA. Bone densitometry in Canadian children 8–17 years of Age. Calcif Tissue Int. 1996;59:344–351. doi: 10.1007/s002239900138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rauch F, Plotkin H, DiMeglio L, Engelbert RH, Henderson RC, Munns C, Wenkert D, Zeitler P. Fracture prediction and the definition of osteoporosis in children and adolescents: the ISCD 2007 Pediatric Official Positions. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, Borgstrom F, Strom O, McCloskey E. FRAX and its applications to clinical practice. Bone. 2009;44:734–743. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.01.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faulkner KG, Gluer CC, Estilo M, Genant HK. Cross-calibration of DXA equipment: upgrading from a Hologic QDR 1000/W to a QDR 2000. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;52:79–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00308312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fonseca AS, Szejnfeld VL, Terreri MT, Goldenberg J, Ferraz MB, Hilario MO. Bone mineral density of the lumbar spine of Brazilian children and adolescents aged 6 to 14 years. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:347–352. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000300008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalkwarf HJ, Zemel BS, Gilsanz V, Lappe JM, Horlick M, Oberfield S, Mahboubi S, Fan B, Frederick MM, Winer K, Shepherd JA. The bone mineral density in childhood study: bone mineral content and density according to age, sex, and race. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2087–2099. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelly TL, Specker BL, Binkely T, Zemel BS, Leonard MB, Kalkwarf HJ, Moyer-Mileur L, Shepard JA. Pediatric BMD reference database for US white children. Bone. 2005;36:S102. [Google Scholar]