Abstract

Background and Purpose

Infections are common following stroke and associated with worse outcome. Clinical trials evaluating the benefit of prophylactic antibiotics have produced mixed results. This study explores the possibility that antibiotics of different classes may differentially affect stroke outcome.

Methods

Lewis rats were subjected to transient cerebral ischemia (2 hrs) and survived for 1 month. The day after stroke they were randomized to therapy with ceftiofur (a β-lactam antibiotic), enrofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone antibiotic) or vehicle (as controls) and underwent the equivalent of 7 days of treatment. Behavioral tests were performed weekly until sacrifice. In a subset of animals, histology was done.

Results

There were no differences in outcomes at 24 hours or 1 week after stroke among the different groups. At 1 month after stroke, however, performance on the rotarod was worse in enrofloxacin treated animals when compared to control animals.

Conclusions

Independent of infection, the antibiotic enrofloxacin was associated with worse stroke outcome. These data echo the clinical observations to date and suggest that the secondary effects of antibiotics on stroke outcome should be considered when treating infection in subjects with stroke. The mechanism by which this antibiotic affects outcome needs to be elucidated.

Keywords: stroke, outcome, antibiotics, fluoroquinolone, β-lactam

Studies show that patients who become infected in the immediate post-stroke period have increased morbidity and mortality in comparison to patients who remain infection free.1 Trials of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent post-stroke infection, however, have produced mixed results, which are summarized as follows: levofloxacin did not prevent infection and was associated with worse outcome2, moxifloxacin did not prevent infection nor affect outcome3, mezlocillin both prevented infection and improved outcome4, and minocycline improved outcome (the effect on infection was not assessed).5 All of these studies were relatively small single center trials, but the disparate findings suggest that the antibiotic class itself may influence stroke outcome. For instance, both minocycline and β-lactam antibiotics have putative neuroprotective properties while fluoroquinolone antibiotics may be neurotoxic.6, 7 We thus hypothesized that antibiotics of different classes may differentially affect outcome in experimental stroke. To address this possibility, we compared behavioral and histologic outcomes from stroke in animals treated with ceftiofur, a β-lactam antibiotic, enrofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic, and vehicle as controls.

Methods

Animals

Male Lewis rats (275–325 grams) were purchased from Taconic Farms. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO)

Anesthesia was induced with 5% and maintained with 1.5% isoflurane. After midline neck incision, the right common carotid, internal carotid and pterygopalantine arteries were ligated. A monofilament suture (4.0) was inserted into the common carotid artery and advanced into the internal carotid artery.8 Animals were maintained at normothermia during surgery and reperfused 2 hours after MCAO. Rectal temperature and body weight were assessed at set time intervals. Animals were sacrificed 1 month after MCAO.

Antibiotic Administration

Twenty-four hours after MCAO, animals were randomly treated with ceftiofur or enrofloxacin (according to veterinarian suggested dosing regimens). Briefly, ceftiofur (10 mg/kg) was given subcutaneously daily for 7 days (days 1–8 after MCAO) and enrofloxacin (20 mg/kg) was given subcutaneously on days 1 and day 5 after MCAO. Control animals received a matched volume of vehicle at the same time points.

Behavioral Outcomes

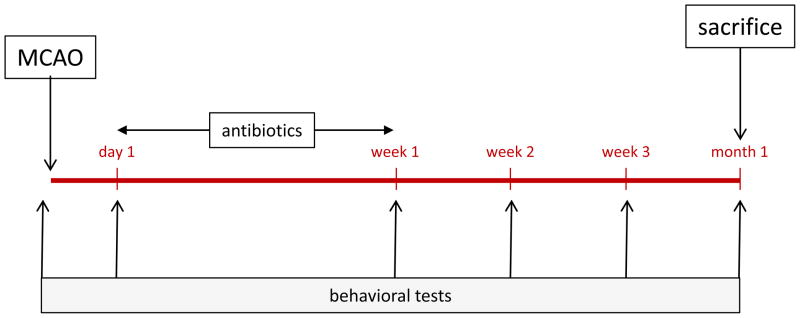

The neurological score of animals undergoing MCAO was determined at routine intervals up to 1 month after MCAO.9 Animals were trained on the rotarod prior to MCAO. After MCAO, rotarod performance was assessed weekly and the median time they were able to remain on the rotarod over 3 trials determined. Performance of the foot fault test was assessed at these time points and the results expressed as a percentage of foot faults per total number of steps taken.10 The experimental protocol is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol.

Immunologic Studies

At the time of sacrifice, lymphocytes were isolated from both the ischemic and non-ischemic hemispheres of the brain. The total number of lymphocytes was determined using a hematocytometer. ELISPOT assays were done to detect the secretion of IFN-γ from the cells (R&D Systems). Briefly, cells were cultured in media alone or in media supplemented with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 50 μg/mL, Sigma Aldrich) for 48 hours in 96 well plates (Multiscreen®-IP, Millipore). Plates were developed using standard protocols (R & D Systems). After plate development, spots were counted with the aid of a semi-automated system (AID iSPOT®).

Histology

In a subset of animals, brains were removed at the time of sacrifice, post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, saturated in 30% sucrose for 48 hours, placed in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound, flash frozen in dry ice cooled isopentane and stored at −80°C until sectioning. Coronal sections (20 μm) were taken from Bregma +1.70mm, −0.40mm and −1.80mm. The area of the ischemic and non-ischemic hemispheres at each level was and determined using Image J and cresyl violet stained sections. The degree of atrophy is expressed as the percent of the ischemic hemisphere lost relative to the non-ischemic hemisphere. Sections at −0.40mm were stained with Fluoro-Jade-B (Histo-Chem Inc) and OX-42 (abcam®) and labelled cells counted as previously described.11

Statistics

Parametric data are displayed as mean ± standard deviation (sd) and compared using the t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Dunnett’s test. Non-parametric data are displayed as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Kruskall-Wallis H test. Significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Behavioral Outcomes

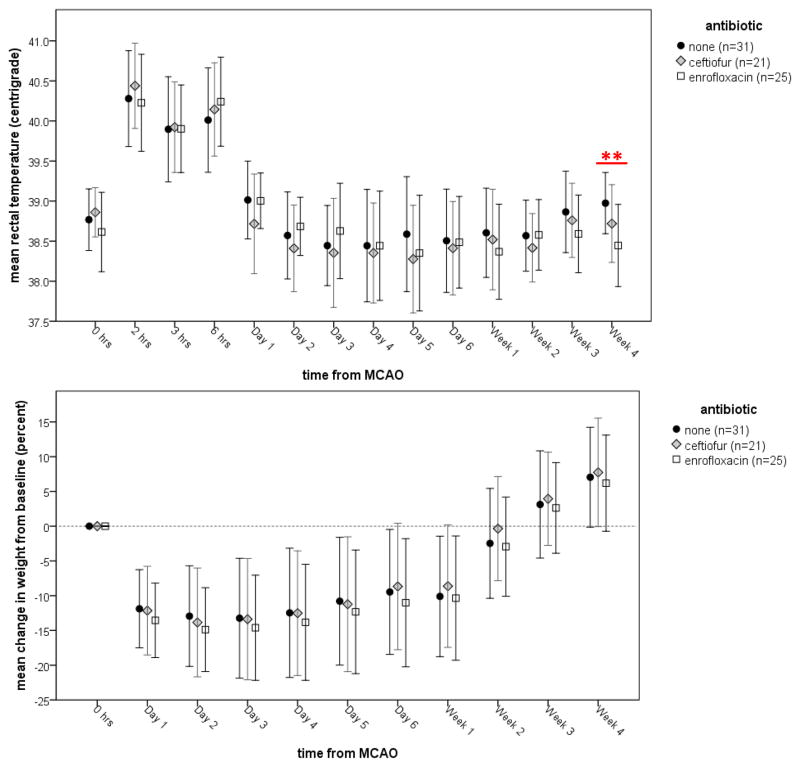

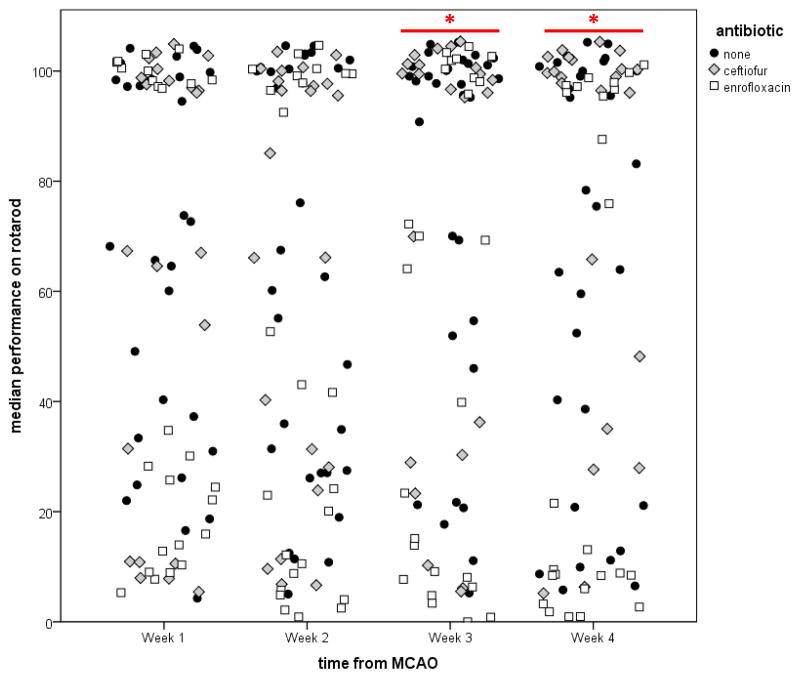

Prior to and immediately after the week of antibiotic treatment, physiologic variables and the neurological score were similar in all groups (Table 1). Figure 2 shows the rectal temperature (a) and changes in weight (b) over the month after stroke. At week 4 after ABX therapy, enrofloxacin treated animals had lower body temperatures. Changes in bodyweight were similar among groups. There were no differences in performance on the foot fault test among the three groups. By 3 weeks after stroke, there were significant differences in the median performance on the rotarod among the three groups (P=0.02). Animals treated with enrofloxacin performed worse than control animals (63 [6, 100] vs. 100 [48, 100]; P=0.01), while the performance of ceftiofur treated animals (100 [29, 100] was similar to control animals. At week 4 after MCAO, the difference among the groups remained significant (P=0.01), with enrofloxacin treated animals performing worse than control animals (14 [5, 100] vs. 78 [21, 100]; P=0.04). Individual animal performances are depicted in Figure 3. At week 4, 14/31 (45%) control animals, 15/22 (68%) ceftiofur treated animals and 8/25 (32%) enrofloxacin treated animals had returned to baseline performance (P=0.04).

Table 1.

Physiologic variables before and after antibiotic therapy.

| antibiotic day 0 (1 day after MCAO) | antibiotic day 7 (8 days after MCAO) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline N=31 |

Ceftiofur N=22 |

Enrofloxacin N=26 |

P | Saline N=31 |

Ceftiofur N=21 |

Enrofloxacin N=25 |

P | |

| Temperature (°C) | 39.2±0.5 | 39.2±0.4 | 39.12±0.4 | NS | 38.6±0.6 | 38.5±0.6 | 38.4±0.6 | NS |

| Change in body weight (%) | −9.5±3.8 | −8.7±5.1 | −10.2±3.2 | NS | −10.1±8.7 | −8.6±8.8 | −10.4±8.9 | NS |

| Neurological Score | 3.0 (2.5, 3.0) | 3.0 (2.4, 3.0) | 3.0 (2.5, 3.0) | NS | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 1.1) | 0.5 (0.0, 1.5) | NS |

MCAO=middle cerebral artery occlusion, NS=not significant (P>0.10)

Figure 2.

Changes in temperature (a) and weight (b) over time. Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation. Statistics are by ANOVA; **P<0.01 in comparison to control.

Figure 3.

Rotarod performance is worse in enrofloxacin treated animals by 3 weeks after stroke and remains so at 4 weeks. Dot plots depict the individual animal data. *P<0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis H test.

Immunologic Assays

There were no differences in the number of lymphocytes or the IFN-γ secretion of the lymphocytes isolated from the ischemic hemisphere one month after stroke (Table 2). In the non-ischemic hemisphere, however, ceftiofur treated rats had fewer lymphocytes, but the number of lymphocytes secreting IFN-γ was significantly augmented in response to LPS stimulation.

Table 2.

Characteristics of lymphocytes isolated from the brain in antibiotic treated rats.

| infarcted hemisphere | non-infarcted hemisphere | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline N=19 |

Ceftiofur N=13 |

Enrofloxacin N=20 |

P | Saline N=19 |

Ceftiofur N=13 |

Enrofloxacin N=20 |

P | |

| total number of lymphocytes (×106) | 7.2±2.2 | 6.3± 2.6 | 6.6±2.6 | NS | 7.7±2.9 | 5.2±2.1 | 6.8±2.8 | <0.05 |

| relative increase in number of lymphocytes secreting IFN-γ in response to LPS | 2.2±2.0 | 1.7±1.2 | 1.9±1.4 | 1.5±0.7 | 2.8±1.5 | 1.8±1.3 | 0.02 | |

IFN=interferon, LPS=lipopolysaccharide, NS=not significant (P>0.10)

Histologic Analyses

Histology showed no difference in the degree of hemispheric atrophy among ceftiofur treated, enrofloxacin treated and control animals. Similarly, there were no differences in the number of microglia stained with OX-42 or the number of degenerating neurons stained with Fluoro-Jade-Bs among antibiotic treated and control animals.

Discussion

Given the disparate results of the trials of antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with acute stroke, this study was undertaken to determine if the class of antibiotics may affect stroke outcome independent of infection. That antibiotics may have “off-target” effects has been appreciated for decades, and the potential for antibiotics to affect the brain is demonstrated by the propensity of many antibiotics to lower the seizure threshold. In this study we used ceftiofur as a representative of the β-lactam class of antibiotics and enrofloxacin as representative of the fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics. Both ceftiofur and enrofloxacin were developed for veterinary use and are used widely throughout the animal kingdom, especially in food animals.12, 13

As a class, fluoroquinolones inhibit γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-A receptor binding; at least some of these drugs may also act at the NMDA receptor and can alter K+ currents.14–18 In the initial clinical trials aimed at assessing the antibacterial properties of the fluoroquinolones, neurological symptoms like dizziness, headache and sleep disturbances were relatively common; hallucinations, depression, and seizures were also reported.19 Multiple Reports of fluoroquinolone induced delirium and non-convulsive status epilepticus can also be found in the literature.20–25 Enrofloxacin, the fluoroquinolone used in this study, has been linked to retinal cell death in felines.26 Under normal circumstances the accumulation of fluoroquinolones in the brain is limited via P-glycoprotein efflux mechanism.27–29 In the setting of stroke, however, it is likely that this efflux mechanism becomes dysfunctional, which means that the concentration of these drugs, especially in the peri-infarct region, would rise, thus increasing the potential for CNS toxicity.

The β-lactam ABXs are well known for their ability to induce seizures. In most experimental studies, these drugs are applied directly to the brain to precipitate seizures; in excessive doses, systemic administration may also cause seizures.30 Similar to the fluoroquinolones, the β-lactams are thought to cause seizures through inhibition of GABA-A receptors.31 More recent data, however, suggest that β-lactam antibiotics may also be neuroprotective by virtue of their ability to induce glutamate transporter expression.32 Ceftriaxone, a clinically used β-lactam antibiotic, has been shown to improve outcome in experimental models of stroke.33 We found no reports regarding potential neuroprotective effects of ceftiofur, the β-lactam used in this study. Antibiotics in other classes, like minocycline, have also been found to affect neurological outcome following stroke, but these antibiotics do not have broad spectrum activity against hospital acquired bacterial pathogens and are rarely used in the clinical setting.34–38

In addition to a direct effect on brain, antibiotics might also affect the development of the immune response, which can indirectly affect stroke outcome. For instance, both in vitro and in vivo studies show that fluoroquinolones suppress the release of inflammatory cytokines (particularly TNF-α) from lymphocytes and monocytes while increasing IL-10.39–41 The β-lactam antibiotics similarly modulate the production of inflammatory cytokines.42–47 And both ceftiofur and enrofloxacin appear to decrease B cell maturation.48 In our study, the number of lymphocytes in the ischemic hemisphere and their ability to respond to LPS was similar in all three groups. In the non-infarcted hemisphere, however, the number of lymphocytes was relatively decreased in ceftiofur treated animals, but their ability to respond to LPS relatively increased compared to enrofloxacin treated and control animals. Whether these immunological effects of ABXs are responsible for modulating stroke outcome or the effects are related to a more direct effect of the drugs on neural cells is unclear.

In the current study, neurologic outcomes were similar among animals randomized to treatment with ceftiofur or enrofloxacin and control animals at 24 hours and 8 days after MCAO (and 7 days of antibiotics), suggesting that baseline stroke severities were also similar. By 4 weeks after MCAO (and 3 weeks after cessation of ABX), however, those animals that received the fluoroquinolone antibiotic enrofloxacin performed worse than control animals on the rotarod. (We previously showed that in Lewis rats, the rotarod is the most sensitive measure of long-term stroke outcome.49) These data suggest that antibiotic treatment with enrofloxacin put in motion a process that affected stroke recovery. Gross histologic analysis showed no difference in the degree of brain atrophy among antibiotic treated and control animals at one month. Further, in the relatively small subset of animals in which we performed immunocytochemistry, there was no difference in the number of cells labelled with OX-42 (microglia) or Fluoro-Jade B. Of note, studies suggest that fluoroquinolones have the capacity to impair both differentiation and proliferation of embryonic brain cells in culture50; the β-lactam antibiotic ceftriaxone, on the other hand, has been shown to upregulate neurotrophins in the peri-infarct zone.33 Whether more detailed histologic analyses in larger animal cohorts would reveal differences between groups is not known. The antibiotics used in this study were drugs developed for veterinary use, but are representative of the major antibiotic classes (fluoroquinolones and β-lactams) used in patients with post-stroke infections. Further, a veterinary study showed that enrofloxacin, but not ceftiofur, reduced equine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell viability in vitro 51, again suggesting that the “off-target” effects of these drugs may be significant.

In summary, our data show that the fluoroquinolone antibiotic enrofloxacin started 1 day after MCAO can profoundly affect stroke outcome in uninfected animals, at least as measured by rotarod performance. The mechanisms by which this antibiotic impacts outcome is unclear but warrants further investigation since these drugs are commonly used in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

NINDS 5R01NS056457

Footnotes

Disclosures

There are no disclosures.

References

- 1.Westendorp WF, Nederkoorn PJ, Vermeij JD, Dijkgraaf MG, van de Beek D. Post-stroke infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamorro A, Horcajada JP, Obach V, Vargas M, Revilla M, Torres F, et al. The early systemic prophylaxis of infection after stroke study: A randomized clinical trial. Stroke. 2005;36:1495–1500. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170644.15504.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harms H, Prass K, Meisel C, Klehmet J, Rogge W, Drenckhahn C, et al. Preventive antibacterial therapy in acute ischemic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarz S, Al-Shajlawi F, Sick C, Meairs S, Hennerici MG. Effects of prophylactic antibiotic therapy with mezlocillin plus sulbactam on the incidence and height of fever after severe acute ischemic stroke: The mannheim infection in stroke study (miss) Stroke. 2008;39:1220–1227. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.499533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lampl Y, Boaz M, Gilad R, Lorberboym M, Dabby R, Rapoport A, et al. Minocycline treatment in acute stroke: An open-label, evaluator-blinded study. Neurology. 2007;69:1404–1410. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000277487.04281.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stock ML, Fiedler KJ, Acharya S, Lange JK, Mlynarczyk GS, Anderson SJ, et al. Antibiotics acting as neuroprotectants via mechanisms independent of their anti-infective activities. Neuropharmacology. 2013;73:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Sarro A, De Sarro G. Adverse reactions to fluoroquinolones. An overview on mechanistic aspects. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:371–384. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Tsuji M, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski H. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion: Evaluation of the model and development of a neurologic examination. Stroke. 1986;17:472–476. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lubics A, Reglodi D, Tamas A, Kiss P, Szalai M, Szalontay L, et al. Neurological reflexes and early motor behavior in rats subjected to neonatal hypoxic-ischemic injury. Behav Brain Res. 2005;157:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zierath D, Schulze J, Kunze A, Drogomiretskiy O, Nhan D, Jaspers B, et al. The immunologic profile of adoptively transferred lymphocytes influences stroke outcome of recipients. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2013;263:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hornish RE, Kotarski SF. Cephalosporins in veterinary medicine - ceftiofur use in food animals. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:717–731. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroder J. Enrofloxacin: A new antimicrobial agent. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1989;60:122–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unseld E, Ziegler G, Gemeinhardt A, Janssen U, Klotz U. Possible interaction of fluoroquinolones with the benzodiazepine-gabaa-receptor complex. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akaike N, Shirasaki T, Yakushiji T. Quinolones and fenbufen interact with gabaa receptor in dissociated hippocampal cells of rat. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:497–504. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.2.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lode H. Potential interactions of the extended-spectrum fluoroquinolones with the cns. Drug Saf. 1999;21:123–135. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199921020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimpfel W, Dalhoff A, von Keutz E. In vitro modulation of hippocampal pyramidal cell response by quinolones: Effects of ha 966 and gamma-hydroxybutyric acid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2573–2576. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang LR, Li MH, Cheng NN, Chen BY, Wang YM. Inhibition by fluoroquinolones of k(+) currents in rat dissociated hippocampal neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;462:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertino J, Jr, Fish D. The safety profile of the fluoroquinolones. Clin Ther. 2000;22:798–817. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80053-3. discussion 797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiangkitiwan B, Doppalapudi A, Fonder M, Solberg K, Bohner B. Levofloxacin-induced delirium with psychotic features. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2008;30:381–383. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isaacson SH, Carr J, Rowan AJ. Ciprofloxacin-induced complex partial status epilepticus manifesting as an acute confusional state. Neurology. 1993;43:1619–1621. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1619-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandez-Torre JL. Levofloxacin-induced delirium: Diagnostic considerations. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:614. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slobodin G, Elias N, Zaygraikin N, Sheikh-Ahmad M, Sabetay S, Weller B, et al. Levofloxacin-induced delirium. Neurol Sci. 2009;30:159–161. doi: 10.1007/s10072-009-0027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rfidah EI, Findlay CA, Beattie TJ. Reversible encephalopathy after intravenous ciprofloxacin therapy. Pediatr Nephrol. 1995;9:250–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00860763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reeves RR. Ciprofloxacin-induced psychosis. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26:930–931. doi: 10.1177/106002809202600716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford MM, Dubielzig RR, Giuliano EA, Moore CP, Narfstrom KL. Ocular and systemic manifestations after oral administration of a high dose of enrofloxacin in cats. Am J Vet Res. 2007;68:190–202. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.68.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ooie T, Terasaki T, Suzuki H, Sugiyama Y. Quantitative brain microdialysis study on the mechanism of quinolones distribution in the central nervous system. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:784–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alvarez AI, Perez M, Prieto JG, Molina AJ, Real R, Merino G. Fluoroquinolone efflux mediated by abc transporters. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:3483–3493. doi: 10.1002/jps.21233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Lange EC, Marchand S, van den Berg D, van der Sandt IC, de Boer AG, Delon A, et al. In vitro and in vivo investigations on fluoroquinolones; effects of the p-glycoprotein efflux transporter on brain distribution of sparfloxacin. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000;12:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(00)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schliamser SE, Cars O, Norrby SR. Neurotoxicity of beta-lactam antibiotics: Predisposing factors and pathogenesis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;27:405–425. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugimoto M, Uchida I, Mashimo T, Yamazaki S, Hatano K, Ikeda F, et al. Evidence for the involvement of gaba(a) receptor blockade in convulsions induced by cephalosporins. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:304–314. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, Haenggeli C, Huang YH, Bergles DE, et al. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature. 2005;433:73–77. doi: 10.1038/nature03180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thone-Reineke C, Neumann C, Namsolleck P, Schmerbach K, Krikov M, Schefe JH, et al. The beta-lactam antibiotic, ceftriaxone, dramatically improves survival, increases glutamate uptake and induces neurotrophins in stroke. J Hypertens. 2008;26:2426–2435. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328313e403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Nozako M, Hazekawa M, Mishima S, Fujioka M, et al. Delayed treatment with minocycline ameliorates neurologic impairment through activated microglia expressing a high-mobility group box1-inhibiting mechanism. Stroke. 2008;39:951–958. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.495820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chu LS, Fang SH, Zhou Y, Yu GL, Wang ML, Zhang WP, et al. Minocycline inhibits 5-lipoxygenase activation and brain inflammation after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:763–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weng YC, Kriz J. Differential neuroprotective effects of a minocycline-based drug cocktail in transient and permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Exp Neurol. 2007;204:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hewlett KA, Corbett D. Delayed minocycline treatment reduces long-term functional deficits and histological injury in a rodent model of focal ischemia. Neuroscience. 2006;141:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu L, Fagan SC, Waller JL, Edwards D, Borlongan CV, Zheng J, et al. Low dose intravenous minocycline is neuroprotective after middle cerebral artery occlusion-reperfusion in rats. BMC Neurol. 2004;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dalhoff A, Shalit I. Immunomodulatory effects of quinolones. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:359–371. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calbo E, Alsina M, Rodriguez-Carballeira M, Lite J, Garau J. Systemic expression of cytokine production in patients with severe pneumococcal pneumonia: Effects of treatment with a beta-lactam versus a fluoroquinolone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2395–2402. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00658-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krehmeier U, Bardenheuer M, Voggenreiter G, Obertacke U, Schade FU, Majetschak M. Effects of antimicrobial agents on spontaneous and endotoxin-induced cytokine release of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Infect Chemother. 2002;8:194–197. doi: 10.1007/s101560200036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziegeler S, Raddatz A, Hoff G, Buchinger H, Bauer I, Stockhausen A, et al. Antibiotics modulate the stimulated cytokine response to endotoxin in a human ex vivo, in vitro model. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:1103–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brooks BM, Hart CA, Coleman JW. Differential effects of beta-lactams on human ifn-gamma activity. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:1122–1125. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brooks BM, Thomas AL, Coleman JW. Benzylpenicillin differentially conjugates to ifn-gamma, tnf-alpha, il-1beta, il-4 and il-13 but selectively reduces ifn-gamma activity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;131:268–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Padovan E, von Greyerz S, Pichler WJ, Weltzien HU. Antigen-dependent and -independent ifn-gamma modulation by penicillins. J Immunol. 1999;162:1171–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ci X, Li H, Song Y, An N, Yu Q, Zeng F, Deng X. Ceftiofur regulates lps-induced production of cytokines and improves lps-induced survival rate in mice. Inflammation. 2008;31:422–427. doi: 10.1007/s10753-008-9094-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chu X, Song K, Xu K, Zhang X, Song Y, Wang D, et al. Ceftiofur attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10:600–604. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chrzastek K, Madej JP, Mytnik E, Wieliczko A. The influence of antibiotics on b-cell number, percentage, and distribution in the bursa of fabricius of newly hatched chicks. Poult Sci. 2011;90:2723–2729. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kunze A, Zierath D, Drogomiretskiy O, Becker K. Variation in behavioral deficits and patterns of recovery after stroke among different rat strains. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5:569–576. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0337-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Minta M, Wilk I, Zmudzki J. Inhibition of cell differentiation by quinolones in micromass cultures of rat embryonic limb bud and midbrain cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2005;19:915–919. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parker RA, Clegg PD, Taylor SE. The in vitro effects of antibiotics on cell viability and gene expression of equine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Equine Vet J. 2012;44:355–360. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2011.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]