Abstract

Objective

To determine if people with low back pain (LBP) who regularly participated in a rotation-related activity displayed more rotation-related impairments than people without LBP who did and did not participate in the activity.

Design

Secondary analysis of data from a case-control study.

Setting

Musculoskeletal analysis laboratory at an academic medical center.

Participants

A convenience sample of 55 participants with LBP who participated in a rotation-related sport, 26 back healthy controls who participated in a rotation-related sport (BHC+RRS) and 42 back healthy controls who did not participate in a rotation-related sport (BHC-RRS). Participants were matched based on age, gender, and activity level.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

The total number of rotation-related impairments and asymmetric rotation-related impairments identified during a standardized clinical examination.

Results

Compared to the BHC-RRS group, both the LBP and BHC+RRS groups displayed significantly more (1) rotation-related impairments (LBP: p<.001; BHC+RRS: p=.015) (2) asymmetric rotation-related impairments (LBP: p=.006; BHC+RRS: p=.020) and (3) rotation-related impairments with trunk movement tests (LBP: p=.002; BHC+RRS: p<.001). The LBP group had significantly more rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests than both of the back healthy groups (BHC+RRS: p=.011; BHC-RRS: p<.001).

Conclusions

LBP and BHC+RRS groups demonstrated a similar number of total rotation-related impairments and asymmetric rotation-related impairments, and these numbers were greater than those of the BHC-RRS group. Compared to people without LBP, people with LBP displayed more rotation-related impairments when moving an extremity. These findings suggest that impairments associated with extremity movements may be associated with having a LBP condition.

Keywords: low back pain, spine, rotation, sports

Low back pain (LBP) affects 60–80% of the US population during adulthood.1, 2 Activities involving repeated movements of the trunk during work and sports have been found to be associated with LBP development.3–11 However, not everyone exposed to these activities develops LBP. A possible reason that some people develop LBP while others do not may be related to the strategies a person adopts as he or she performs specific activities. The strategies are proposed to (1) develop as the result of repeated trunk movements in specific directions, e.g., flexion, extension, or rotation associated with an activity, and (2) become generalized across several activities used during the day.11–16 Repeated use of these strategies is believed to contribute to musculoskeletal and neural adaptations that result in direction-specific movement impairments that are evident during a clinical examination.12 Typically, the impairments are characterized by early movement of one or more lumbar joints in a specific direction relative to movement of other lumbar joints and other regions, such as the thoracic spine or hip.15–18 Repeated use of the same movement strategies is proposed to contribute to sub-failure magnitude loading in specific tissues and localized concentrations of tissue stress.19 The effect of the stress accumulates rapidly because the (1) lumbar spine moves more readily than other regions during activities,12, 14, 15, 18, 20–23 and (2) patterns are used repeatedly across multiple activities throughout the day. The proposed result is insufficient rest for normal tissue adaptation. Repetitive loading of the same tissue could also alter the tissue’s tolerance over time, accelerate the rate of mechanical injury, and potentially lead to tissue degeneration.11, 12, 19

We have developed a standardized examination that includes tests to assess direction-specific movement impairments adopted by a person with LBP.24 The examination includes tests of movements of the trunk and extremities. Tests of extremity movements are included because they transfer loads to the lumbar region. For example, one test requires the person to flex his or her knee while in prone. During the knee flexion motion, the examiner focuses on the lumbopelvic region. Given the assumption that the spine should remain relatively stable during the lower extremity movement, the test would be positive for a trunk rotation-related impairment if the participant’s lumbopelvic region rotated early during flexion of the knee.11, 12 Asymmetry of lumbar region movement impairments also are assessed because of the documented increased risk of LBP associated with asymmetric trunk movements.17, 18, 25 An impairment is considered asymmetric if the participant displays the impairment on only one side of the body. For example, if a participant displays early lumbopelvic rotation with right knee flexion but not left knee flexion, he or she would display asymmetry of lumbopelvic rotation.

The purpose of this secondary analysis was to examine if people with LBP who regularly participated in a rotation-related sport (LBP) displayed more trunk rotation-related impairments than people without LBP who (1) participated in a rotation-related sport (BHC+RRS), and (2) did not participate in a rotation-related sport (BHC-RRS). We hypothesized that the LBP and BHC+RRS groups would display more (1) rotation-related impairments, and (2) asymmetric rotation-related impairments than the BHC-RRS group. We also hypothesized that the LBP group would display more rotation-related impairments than the BHC+RRS group. Impairments that are consistently identified across a variety of movement tests can provide insight into the direction-specific activities that may contribute to a person’s LBP.

METHODS

Study Participants

Study participants were divided into three groups, LBP, BHC+RRS, and BHC-RRS. Inclusion criteria required all participants to be between the ages of 18 and 40 and able to understand and sign an informed consent form. Participants were matched based on age, gender, and activity level. Participants in the LBP group had to have chronic or recurrent LBP26 and play a rotation-related sport that the participant reported was associated with an increase in LBP symptoms. Chronic LBP was defined as the presence of LBP on more than half the days in a year in a single period or in multiple episodes.26 Recurrent LBP was defined as the presence of LBP on less than half the days in a year, occurring in multiple episodes over the year.26 A rotation-related sport was defined as a sport that involved repeated rotational movements of the trunk and hips during participation in the activity. The LBP group was required to participate in the rotation-related sport on a regular basis, defined as a minimum of 1–2 times per week. Participants were included in the BHC+RRS group if they (1) reported no history of LBP that limited performance of daily activities for greater than 3 consecutive days or for which they sought medical or allied health treatment,27 and (2) participated in a rotation-related sport at least 1–2 times per week. Participants were included in the BHC-RRS group if they (1) reported no history of LBP that limited performance of daily activities for greater than 3 consecutive days or for which they sought medical or allied health treatment,27 and (2) did not participate in rotation-related sports on a regular basis. Exclusion criteria included a history of spinal fracture or surgery, spinal stenosis, osteoporosis, disc pathology, etiology of LBP other than lumbar spine (e.g., hip joint), previous lower extremity surgery, a systemic inflammatory condition, current pregnancy, or other serious medical condition. Participants for all groups were recruited from the St. Louis metropolitan region. In particular, we targeted university- and community-based athletic centers, and varsity, club-level, and intramural racquet sports teams in the region.

Initially, 130 participants (LBP: n = 61; BHC+RRS: n = 26; BHC-RRS: n = 43) were enrolled in the study. After preliminary screening of participant characteristics, 7 of the participants did not meet our inclusion criteria and were not included in the secondary analysis. Reasons for exclusion included the following: (1) plantar fasciitis rather than LBP (n = 1), (2) LBP due to trauma from a motor vehicle accident (n = 1), (3) a history of back surgery (n = 1), and (4) refusal to complete the clinical examination (n = 4). Our final sample included 55 participants in the LBP group, 26 participants in the BHC+RRS group, and 42 participants in the BHC-RRS group. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University School of Medicine. All participants provided written informed consent for study participation.

Measurement Procedures

Self Report Measures

Participants completed self-report measures on the day of testing. The measures included a demographic and LBP history form and the Baecke Habitual Activity Questionnaire.28 The LBP group completed two additional questionnaires, a sport-related activity questionnaire and the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire.29 The demographic and LBP history questionnaire included questions about participants and their LBP characteristics. The sport-related activity questionnaire examined characteristics of sport-specific activities that may contribute to the development or persistence of LBP similar to the lifetime sporting activities questionnaire described by Videman and colleagues.30 The Oswestry LBP Disability Questionnaire is a LBP-specific measure that provides information about a participant’s perceived LBP-related functional limitations. The questionnaire includes 10 items and uses a 100-point scale, with higher numbers indicating more limitation.29

Clinical Examination

Participants were assessed using a standardized clinical examination.12, 24 The physical examination portion included tests of movements and postures performed in different positions. Judgments of alterations in movements and postures were made and symptoms were assessed with each test. Included in the physical examination were 10 clinical tests to assess rotation-related impairments, listed in Table 1. Procedures regarding the clinical tests have been described previously.12, 24, 31 Briefly, a rotation-related impairment was judged to be present if (1) the lumbar spine moved in relation to the proximal joints during the first 50% of the overall movement, or (2) a side-bending alignment or movement was displayed during a test. Tests were conducted at the Washington University Musculoskeletal Analysis Laboratory by a trained clinician with 19 years of experience. Clinician training has been described elsewhere.24 Appendix A includes the procedures and operational definitions for positive responses for each test. Tests were performed in the same order for all participants.

Table 1.

List of clinical tests and position of participant during clinical test

| Clinical Tests | Position of Participant |

|---|---|

| Trunk Movement Tests | |

| Lumbar spine asymmetry with side bending | Standing |

| Asymmetrical trunk rotation | Sitting |

| Lateral pelvic tilt with rocking back | Quadruped |

| Pelvic rotation with rocking back | Quadruped |

| Extremity Movement Tests | |

| Lumbar spine rotation with right and left active knee extension | Sitting |

| Lumbar spine shift with right and left active knee extension | Sitting |

| Lumbopelvic rotation with right and left hip lateral rotation and abduction | Supine |

| Lumbopelvic rotation with right and left knee flexion | Prone |

| Lumbopelvic rotation with right and left hip lateral rotation | Prone |

| Lumbar rotation with right and left single arm lift | Quadruped |

Outcome Variables

Outcome measures for all 3 groups included the number of (1) rotation-related impairments, and (2) asymmetric rotation-related impairments. The number of rotation-related impairments was further separated into the number with (3) either a right or left extremity movement test, and (4) overt trunk movement tests.

Data Analysis

All data analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 for Windowsa (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance for all analyses was defined as a two-tailed p-value ≤ 0.05. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Participant characteristics were analyzed using either one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests or the chi-square test for independence as appropriate. One-way ANOVA tests were used to test for differences among groups in the (1) number and type of rotation-related impairments, i.e., occur during extremity movement test vs. overt trunk movement test, and (2) number of asymmetric rotation-related impairments. Tukey’s HSD statistic was calculated in the instance that an ANOVA test was significant. Chi-square tests were used to test for differences between groups in the prevalence of individual impairments. Eta squared, the phi coefficient, Cohen’s d statistics and standard error were calculated as appropriate to index effect sizes for the different comparisons.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 2. The LBP group had a significantly higher BMI than the BHC-RRS group (mean difference= 1.67 kg/m2). The LBP group history and LBP characteristics are provided in Table 3.

Table 2.

Participant Demographics

| Characteristic | Group

|

Statistical Test Value, p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBP (N=55) | BHC+RRS (N=26) | BHC-RRS (N=42) | ||

| Age (years)* | 28.89 ± 9.58 | 26.31 ± 7.77 | 27.74 ± 7.41 | F = .831, p = .438 |

| Height (cm)* | 172.17 ± 10.03 | 172.72 ± 8.27 | 170.69 ± 10.52 | F = .417, p = .660 |

| Weight (kg)* | 74.83 ± 16.17 | 75.38 ± 14.44 | 68.44 ± 12.53 | F = 2.791, p = .065 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 25.03 ± 3.85† | 25.08 ± 3.43 | 23.36 ± 2.77 | F = 3.371, p = .038 |

| Baecke Habitual Activity Questionnaire Score* | 8.29 ± 0.77 | 8.77 ± 1.22 | 8.16 ± 1.30 | F = 2.738, p = .069 |

| Gender (n (%)) | ||||

| Male | 36 (65%) | 19 (73%) | 24 (57%) | χ2 =1.840, p = .399 |

| Female | 19 (35%) | 7 (27%) | 18 (43%) | |

| Hand Dominance (n (%)) | ||||

| Right | 51 (93%) | 24 (92%) | 40 (95%) | χ2 = .323, p = .851 |

| Left | 4 (7%) | 2 (8%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Marital Status (n (%)) | ||||

| Single (never married) | 34 (62%) | 22 (85%) | 30 (72%) | χ2 =5.711, p = .222 |

| Married/Living with significant other | 17 (31%) | 4 (15%) | 11 (26%) | |

| Divorced/Separated | 4 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity (n (%)) | ||||

| Caucasian | 34 (62%) | 14 (54%) | 24 (57%) | χ2 = 8.027, p = .431 |

| Black/African American | 5 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (12%) | |

| Asian | 12 (21%) | 10 (39%) | 11 (26%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 2 (4%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Employment Status (n (%)) | ||||

| Currently working | 23 (42%) | 11 (42%) | 22 (53%) | χ2 = 6.252, p = .794 |

| Homemaker | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Student | 27 (49%) | 13 (50%) | 19 (45%) | |

| Retired (not due to health) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unemployed | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Education Completed (n (%)) | ||||

| Less than high school | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | χ2 = 3.648, p = .962 |

| Graduated from high school | 3 (5%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Completed 1–3 years of college | 15 (27%) | 8 (31%) | 10 (24%) | |

| Graduated w/ a 2 year college degree | 2 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Graduated w/ a 4 year college degree | 22 (40%) | 11 (42%) | 15 (36%) | |

| Completed post-graduate/professional degree | 13 (24%) | 5 (19%) | 13 (31%) | |

| History of LBP problems in family | ||||

| Yes | 17 (31%) | 7 (27%) | 13 (31%) | χ2 = .156, p= .925 |

| No | 38 (69%) | 19 (73%) | 29 (69%) | |

Values are mean ± SD

Abbreviations: Low Back Pain (LBP); Back Healthy Control + Rotation Related Sport (BHC+RRS); Back Healthy Control - Rotation Related Sport (BHC-RRS)

Significant difference between LBP and BHC-RRS, p < .05

Significant values in bold face

Table 3.

Pain history and low back pain characteristics for people in the Low Back Pain Group

| Characteristic | LBP (N=55) |

|---|---|

| Number of years since first episode of LBP* | 9.17 ± 6.51 |

| First LBP episode was caused by rotation-related sport | |

| Yes | 23 (42%) |

| No | 27 (49%) |

| Unsure or Unknown | 5 (9%) |

| Current episode of back pain is a result of playing rotation-related sport | |

| Yes | 34 (62%) |

| No | 13 (24%) |

| Unsure or Unknown | 8 (14%) |

| Number of episodes of LBP in the past 12 months* | 9.06 ± 13.44 |

| Currently taking medication for LBP problem | |

| Yes | 8 (15%) |

| No | 47 (85%) |

| Oswestry LBP Disability Questionnaire Score* | 15.05 ± 7.58 |

Values are mean ± SD

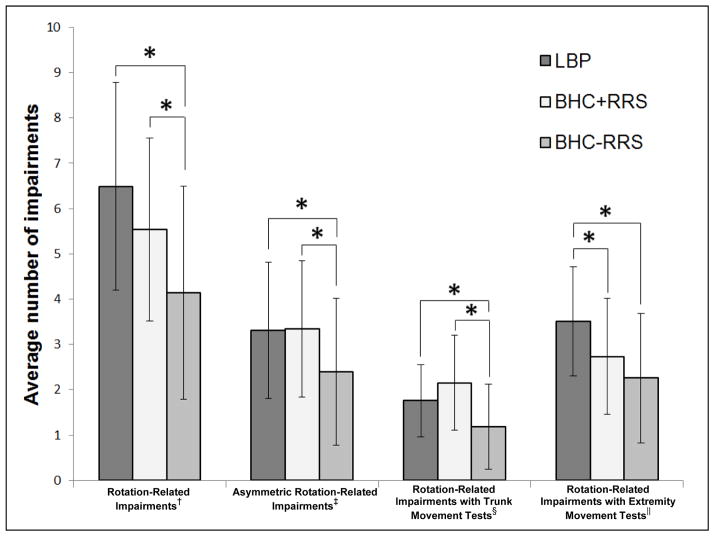

The number of rotation-related impairments for the LBP, BHC+RRS, and BHC-RRS groups is provided in Table 4. Compared to the BHC-RRS group, both groups that played a rotation-related sport displayed significantly more (1) rotation-related impairments (LBP vs. BHC-RRS: mean difference ± SE = 2.35 ± 0.48, t = 4.94, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.65; BHC+RRS vs. BHC-RRS: mean difference ± SE = 1.40 ± 0.56, t = 2.50, p = .015, Cohen’s d = 0.96;), (2) asymmetric rotation-related impairments (LBP vs. BHC-RRS: mean difference ± SE = 0.90 ± 0.32, t = 2.83, p = .006, Cohen’s d = 0.58; BHC+RRS vs. BHC-RRS: mean difference ± SE = 0.94 ± 0.39, t = 2.39, p = .020, Cohen’s d = 0.60), and (3) rotation-related impairments with trunk movement tests (LBP vs. BHC-RRS: mean difference ± SE = 0.57 ± 0.18, t = 3.20, p = .002, Cohen’s d = 1.01; BHC+RRS vs. BHC-RRS: mean difference ± SE = 0.96 ± 0.25, t = 3.93, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.64). The LBP group, however, had significantly more rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests than both of the back healthy groups (LBP vs. BHC+RRS: mean difference ± SE = 0.78 ± 0.30, t = 2.60, p = .011, Cohen’s d = 0.63; LBP vs. BHC-RRS: mean difference ± SE = 1.25 ± 0.28, t = 4.48, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.95). In addition, the back healthy groups (BHC-RRS and BHC+ RRS) did not differ in the number of rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests (mean difference ± SE = 0.47 ± 0.34, t = 1.36, p = .177, Cohen’s d = 0.35) (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Comparison of rotation-related impairments between the Low Back Pain and Back Healthy Control groups

| Measures | Group | Statistical Test Value, p value | Effect Size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBP (N=55) | BHC+RRS (N=26) | BHC-RRS (N=42) | eta squared* | ||

| Total number of positive rotation-related impairments (out of 16) | 6.49 ± 2.29‡ | 5.54 ± 2.02§ | 4.14 ± 2.35 | F = 12.85, p < .001 | 0.18 |

| Total number of asymmetric rotation-related impairments (out of 8) | 3.31 ± 1.50‡ | 3.34 ± 1.50§ | 2.40 ± 1.62 | F = 4.88, p = .009 | 0.08 |

| Total number of rotation-related impairments with trunk movement tests (out of 4) | 1.76 ± 0.80‡ | 2.15 ± 1.05§ | 1.19 ± 0.94 | F = 9.81, p < .001 | 0.14 |

| Total number of positive rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests (out of 6) | 3.51 ± 1.20†‡ | 2.73 ± 1.28 | 2.26 ± 1.43 | F = 10.36, p < .001 | 0.16 |

Values are mean ± SD

Effect size interpretations are as follows: 0.01 = small, 0.06 = medium, 0.14 = large (Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. 1988)

Abbreviations: Low Back Pain (LBP); Back Healthy Control + Rotation Related Sport (BHC+RRS); Back Healthy Control - Rotation Related Sport (BHC-RRS)

Significant difference with post-hoc test between LBP and BHC+RRS, p < .001

Significant difference with post-hoc test between LBP and BHC-RRS, p < .05

Significant difference with post-hoc test between BHC + RRS and BHC - RRS, p < .001

Significant values in bold face

Figure 1.

Difference in the average number of rotation-related impairments, asymmetric trunk rotation-related impairments, rotation-related impairments with trunk movement tests, and rotation-related impairments with an extremity movement test between the low back pain (LBP) and back-healthy controls who play a rotation related sport (BHC+RRS) do not play a rotation-related sport (BHC-RRS). Note: * = p<.01, † = total number of rotation-related impairments possible was 16, ‡ = total number of asymmetric rotation-related impairments possible was 8, § = total number of rotation-related impairments with trunk movement tests possible was 4, || = total number of rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests possible was 6. An impairment was considered asymmetric if the participant displayed an impairment on only one side of the body.

Because the LBP group had significantly more rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests, we examined the prevalence of individual rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests between the LBP and BHC+RRS groups. The data are displayed in Table 5. Compared to the BHC+RRS group, the LBP group displayed a significantly higher percentage of (1) lumbar spine shift with active knee extension in sitting (32% difference), (2) lumbopelvic rotation with hip lateral rotation in prone (33% difference), and (3) lumbar rotation with a single arm lift in quadruped (41% difference).

Table 5.

Percentage of participants in the Low Back Pain and Back Healthy Control + Rotation Related Sport groups who display specific rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests

| Impairment | Group

|

Statistical Test Value, p value | Effect Size*

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBP (N=55) | BHC+RRS (N=26) | Phi coefficient* | ||

| Lumbar spine rotation with active knee extension in sitting on either the right or left side | 21 (39%) | 7 (27%) | χ2 = 1.12, p = .33 | 0.12 |

| Lumbar spine shift with active knee extension in sitting on either the right or left side | 23 (43%) | 3 (11%) | χ2 = 8.08, p = .005 | 0.32 |

| Lumbopelvic rotation with hip lateral rotation and abduction in supine on either the right or left side | 31 (63%) | 19 (73%) | χ2 = 0.74, p = .45 | 0.10 |

| Lumbopelvic rotation with knee flexion in prone on either the right or left side | 28 (53%) | 19 (73%) | χ2 = 2.97, p = .10 | 0.19 |

| Lumbopelvic rotation with hip lateral rotation in prone on either the right or left side | 49 (91%) | 15 (58%) | χ2 = 11.98, p = .002 | 0.39 |

| Lumbar rotation with a single arm lift in quadruped on either the right or left side | 34 (72%) | 8 (31%) | χ2 = 11.84, p = .001 | 0.40 |

Significant values in bold face

Effect size interpretations are as follows: 0.1 = small, 0.3 = medium, 0.5 = large (Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. 1988)

Abbreviations: Low Back Pain (LBP); Back Healthy Control + Rotation Related Sport (BHC+RRS)

DISCUSSION

This study was a secondary analysis to determine if people with LBP who regularly participated in a rotation-related sport displayed more rotation-related impairments than people without LBP who did and did not participate in a rotation-related sport. We hypothesized that people who participated in a rotation-related sport (LBP and BHC+RRS) would display more (1) rotation-related impairments, and (2) asymmetric rotation-related impairments than people who did not participate in a rotation-related sport. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that the groups who played the sport displayed a greater number of rotation-related impairments and asymmetric rotation-related impairments than the group who did not play the sport. Additionally, when examining the differences between the 2 groups who played a rotation-related sport, we found that people with LBP displayed a greater number of rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests. The findings of our study suggest that, although the groups displayed varying numbers of impairments, participation in a rotation-related activity may contribute to an increased number of rotation-related impairments and more asymmetric rotation-related impairments. The key difference between people with LBP and people without LBP that played the sport was the number of rotation-related impairments with extremity movement tests. These impairments may provide important information on why people develop LBP. Additionally, these impairments can be identified through tests from a standardized clinical examination.

Previous research has examined the association between repetitive activities and LBP. Studies that have focused on repetitive occupational activities suggest that duration and intensity of repetitive activities are risk factors for development of LBP.32–35 Similar to occupational activities, many sports also include repetitive activity that may be associated with LBP. Imaging studies have suggested that athletes with LBP who participate in sports with high physical demands on the back, including football, wrestling and gymnastics, tend to have more changes in spinal structures (such as spine degeneration or deformities) than athletes without LBP10, 36, 37 and non-athletes.38 There also is some evidence to suggest that athletes with LBP who participate in a repetitive, rotation-related sport display different end ranges of motion of various joints compared to athletes without LBP who participate in the same sport.25, 39, 40 For example, golfers and tennis players with LBP display limited end-range hip medial rotation25, 39, 40 and lumbar spine extension25 compared to their counterparts without LBP. In a similar study, Scholtes et al15 reported people with LBP who participate in a rotation-related sport displayed earlier and greater lumbopelvic rotation during 2 lower extremity movement tests than people without LBP who did not participate in a rotation-related sport. None of these investigators, however, examined the association between activity type and consistency of impairments displayed across a battery of clinical movement tests from a standardized examination.13, 18, 24 Only Scholtes et al.15 examined the movement pattern displayed during a clinical movement test rather than end-range of motion of a joint.

The results of our study suggest that (1) the type, number, and asymmetry of movement impairments are related to regular participation in a repetitive rotation-related activity, and (2) there may be specific types of rotation-related impairments that increase the risk of development or persistence of LBP more than other impairments. Further, identification of the same type of impairment across multiple tests within a standardized clinical examination can provide clinicians insight into movement impairments that might be adopted by people with LBP during other activities, such as everyday functional activities.

In contrast to previous studies, the current study examined (1) several different rotation-related movement impairments across a multitude of trunk and extremity tests, (2) how people with and people without LBP move across the range of motion, rather than examining end range of motion, and (3) the asymmetry of several movement impairments. These data, in turn provide (1) new evidence that people who play a rotation-related sport have adopted several related movement patterns associated with their repetitive activity, (2) insight into which impairments may be more important to a LBP condition, and, therefore, (3) which impairments likely should be targeted in treatment. Chimenti et al.41 reported on 2 of the 3 groups examined in the current study; the LBP group and the BHC+RRS group. The purpose of the Chimenti study was to examine differences between the two groups in activity level related to sport participation versus activity level related to daily function. A secondary purpose was to examine whether there were differences between the LBP and BHC+RRS group in impairments during 2 of the lower limb movement tests, hip lateral rotation and knee flexion. Impairments during the tests were quantified using a 3-dimensional motion capture system rather than standardized judgments made by a trained clinician. Different from the current study, the LBP and BHC+RRS groups in the Chimenti study were not different in the rotation-related impairment quantified during the hip lateral rotation test. The difference in prevalence reported in the current study and the Chimenti study, however, could be because of the difference between the 2 studies in the methods and criteria used to define an impairment. In the current study, an impairment was present if the clinician judged that the pelvis moved 1/2 inch or more in the first 50% of the hip lateral rotation motion. In the Chimenti study, the authors tested for mean differences in timing of when the pelvis moved during the hip lateral rotation motion between the 2 groups. Thus, in the Chimenti study the definition of an impairment did not include a specific amount of pelvic movement that had to occur in a specific range of hip lateral rotation. The difference in the prevalence of an impairment with the hip lateral rotation test between the LBP and BHC+RRS group we identified in the current study could be because some people in the BHC+RRS group did not move enough, i.e., ½ inch, in the first 50% of the hip motion to be judged to have an impairment during the clinical examination test.

Study Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, shortly after the onset of the original study, the initial clinical examination was modified to measure additional rotation-related variables. Therefore, the first 5 participants in the LBP group did not have data for the additional variables. To ensure the lack of data for these 5 participants did not affect our results, we performed a best-case/worst-case scenario sensitivity analysis. First, we classified all participants’ missing examination variables as impairments and re-calculated our analyses. Then we classified all subjects’ missing examination variables as no impairments and re-calculated our analyses. The results of the sensitivity analyses indicated that these missing variables did not change any of the significant findings described above.

A second limitation is the cross-sectional design of the study, which limited our ability to infer a cause and effect relationship between LBP and the rotation-related impairments. Therefore, we cannot be certain whether the impairments developed as a result of participation in the sport, or the impairments developed because of the presence of LBP. Additionally, because symptoms were assessed during this examination, it was not possible to blind the examiner to participant group. The standardized clinical examination performed by the examiner, however, included pre-defined operational definitions and procedures to help minimize bias when making clinical judgments. The examiner was blinded to which group the symptom-free participants belonged to, i.e., BHC-RRS versus BHC+RRS. Given that there were predicted differences between these two groups in number of rotation-related impairments, it appears that the examiner did adhere to the pre-defined definitions and procedures for judgments of responses during the clinical examination tests.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that compared to the BHC-RRS group, people who participated in a rotation-related sport displayed a greater number of trunk rotation-related impairments and asymmetric trunk rotation-related impairments. Furthermore, we found that the LBP and BHC+RRS groups demonstrated a similar number of total rotation-related impairments and asymmetric rotation-related impairments. People with LBP, however, demonstrated more rotation-related impairments when moving an extremity than the BHC+RRS group. These findings suggest that participation in a rotation-related activity may increase the number of movement impairments a person develops. In addition, rotation-related impairments associated with extremity movements may be associated with having a LBP condition. The specific activities in which a person with LBP participates is related to the type of movement impairments identified on examination, at least for rotation-related impairments. Further research should include prospective investigation to better understand the relationships among impairments, activity type, activity dosage, and LBP. These studies could have important implications for people who regularly participate in activities that involve direction-specific, repetitive trunk and extremity movements.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1 TR000448 and TL1 TR00044 and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, Grant K01HD-01226.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- LBP

low back pain

- BHC+RRS

back healthy controls who participate in rotation-related sport

- BHC-RRS

back healthy controls who does not participate in rotation-related sport

APPENDIX 1

SET UP

Patient is standing with his or her feet pelvis width apart, weight distributed evenly over both lower extremities, arms at his or her sides, and looking straight ahead.

-

Adhesive reinforcement labels are used as markers to help the clinician make visual judgments. The examiner places markers on the following anatomical landmarks:

R acromion process – midpoint between the anterior and posterior aspect of acromion process

L acromion process – midpoint between the anterior and posterior aspect of acromion process

L1 spinous process

S1- ½ way between L5 spinous process and S2 (midpoint between the right and left posterior superior iliac spine)

The examiner draws a horizontal line that bisects the markers on the acromion processes and a vertical line that bisects the markers at L1 and S1 to help the clinician make visual judgments.

PROCEDURES AND OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS FOR JUDGMENTS DURING STANDARDIZED TESTS

-

Lumbar spine asymmetry with side bend in standing

-

Operational definition for asymmetry

The patient displays greater excursion of lumbar side bending or a different pivot point to one side when compared to the other side. A pointer is held vertically to represent starting position of the lumbar spine.

The lumbar spine motion that occurs with side bending in standing is judged visually, based on the criteria, to be different with side bending to one side vs. the other. This is based on the inspection of the shape of the lumbar curve (between the markers at L1 and S1) at the completion of the motion.

-

Criteria for significant degree of difference (at least one of the following must be present):

A difference of 1/2 inch or greater between the vertical location of the apex of the curve with side bending to one side vs. the other.

A difference of 1/2 inch or greater in the amount of lateral excursion of L1 from initial starting alignment with side bending to one side vs. the other.

-

Test procedures

Starting position of patient: The patient stands with his or her feet pelvis width apart, weight born evenly over both lower extremities, arms at his or her sides, and looking straight ahead.

-

Starting position of examiner:

Posterior view, lumbar level.

The examiner instructs the patient to avoid rotation, flexion or extension of the trunk during the side bending movement.

-

Instructions to the patient

“With your feet positioned pelvis width apart, easily bend to your (direction) side as far as you can sliding your arm along your leg, then return to the starting position.”

Mode of obtaining information: Visual inspection.

Judgment: Based on the information obtained visually the examiner makes a decision about the presence of asymmetry of the lumbar region as operationally defined.

-

-

Lumbar spine rotation with active knee extension in sitting

-

Operational definition for lumbar spine rotation

The patient displays greater lumbopelvic excursion on one side when compared to the other side. While the patient is performing active knee extension, the examiner observes and palpates the tissue on either side of the lumbar spine. The patient is asked to extend each knee separately.

The lumbar spine motion that occurs when the patient is extending the knee in sitting is judged visually. The examiner observes the movement of his or her hands palpating the tissue on either side of the lumbar spine with movement of each lower extremity (LE).

-

Criterion for significant degree of rotation:

At the completion of the knee motion the difference in the prominence of the tissue must be 1/2 inch or greater in depth when simultaneously palpating the tissue to either side of the lumbar spine.

-

Test procedure

Starting position of patient: The patient assumes a neutral sitting position. The feet are supported at 90 degrees of dorsiflexion, the hips and knees are at 90 degrees of flexion and neutral hip abduction and adduction, the shoulders are over the hips, and the patient’s hands are in his or her lap.

-

Starting position of examiner:

Posterior view, pelvic level.

The examiner places one hand on each side of the lumbar spine aligning the thumbs to either side of the lumbar spine. The examiner is palpating tissue ~ 2 inches lateral to either side of the spinous processes.

-

Instructions to the patient:

“Easily straighten your (side) knee all the way out, and then return it to the resting position.”

Mode of obtaining information: Visual inspection, palpation.

Judgment: Based on the information obtained visually and by palpation the examiner makes a decision about the presence of rotation of the lumbar region as operationally defined.

-

-

Lumbar spine shift with active knee extension in sitting

-

Operational definition for lumbar spine shift

The patient displays a lateral excursion of the lumbar spine to one side. While the patient is performing active knee extension, the examiner observes the L1 and S1 markers and palpates the tissue on either side of the lumbar spine. The patient is asked to extend each knee separately.

The lumbar spine motion that occurs when the patient is extending the knee in sitting is judged visually. The examiner observes the movement of the L1 marker relative to the S1 marker with movement of each LE.

-

Criterion for significant degree of shift:

During or at the completion of the knee motion the lateral excursion of the L1 marker is equal to or exceeds the diameter of the marker when compared to the initial starting alignment.

-

Test procedure

Starting position of patient: The patient assumes a neutral sitting position. The feet are supported at 90 degrees of dorsiflexion, the hips and knees are at 90 degrees of flexion and neutral hip abduction and adduction, the shoulders are over the hips, and the patient’s hands are in his or her lap.

-

Starting position of examiner:

Posterior view, pelvic level.

The examiner places one hand on each side of the lumbar spine aligning the thumbs to either side of the lumbar spine.

-

Instructions to the patient:

“Easily straighten your (side) knee all the way out, and then return it to the resting position.”

Mode of obtaining information: Visual inspection.

Judgment: Based on the information obtained visually the examiner makes a decision about the presence of lateral shift of the lumbar region as operationally defined.

-

-

Asymmetrical trunk rotation in sitting

-

Operational definition for asymmetry

The patient displays a 20 degree difference between the R and L sides in amount of rotation of the trunk. The examiner uses the markers on the R and L acromion processes to determine whether asymmetry is present.

The trunk motion that occurs with rotation in sitting is judged by visualizing the marker movement and comparing the degree of marker movement side to side. A 20 degree difference or greater of trunk rotation with between rotation to each side must be present for the movement to be asymmetric.

-

Criterion for significant degree of asymmetry:

At the completion of both R and L trunk rotation there is at least a 20 degree difference in trunk motion between the two sides.

-

Test procedure

Starting position of patient: The patient assumes a neutral sitting position. The feet are supported at 90 degrees of dorsiflexion, the hips and knees are at 90 degrees of flexion and neutral hip abduction and adduction, the shoulders are over the hips, and the patient’s arms and hands are across his or her chest.

-

Starting position of examiner:

Superior view, above shoulders.

The examiner kneels on the table so he or she is above the patient’s shoulders. The examiner visually estimates the degree of marker movement with rotation of the trunk to the right and degree of rotation of the trunk to the left.

-

Instructions to the patient:

“Keeping both hips on the table, rotate your trunk to one side, return to the resting position, and then rotate your trunk to the other side.”

Mode of obtaining information: Visual inspection.

Judgment: Based on the information obtained visually the examiner makes a decision about the presence of asymmetry in trunk rotation range of motion as operationally defined.

-

-

Lumbopelvic rotation with hip lateral rotation and abduction in supine

-

Operational definition for lumbopelvic rotation

-

Criterion for significant degree of lumbopelvic rotation:

Using the ASIS contralateral to the moving LE as a visual reference for lumbopelvic motion, 1/2 inch or greater of motion of the ASIS must occur relative to the starting position within the 1st 50% of the hip range of motion.

-

-

Test procedure

Starting position of patient: The patient assumes supine with one LE extended and the opposite LE flexed at the hip and knee, and the foot flat on the table in a comfortable position.

-

Starting position of the examiner:

Side view and above, pelvic level.

The examiner should stand on the side of the LE that is to be tested (moving LE)

-

Procedures:

Each LE should be passively taken through the test motion before carrying out any of the test movements.

The examiner moves each LE passively into hip abduction/lateral rotation to assess the available ROM and to demonstrate the test movement to the patient.

When the patient understands the movement, the examiner has the patient perform unilateral hip abduction/lateral rotation with the LE that is flexed.

The movement is performed separately with each LE.

The examiner lightly touches the ASIS opposite the moving LE to have a visual marker to assess the amount of pelvic movement that is occurring with the LE movement. The palpation should be light so that the patient doesn’t learn how to stabilize the pelvis or receive external stabilization during the testing.

During the test movement the examiner is looking for the amount of pelvic rotation that spontaneously occurs.

-

Instructions to the patient:

“Easily move your (side) leg out to the side as far as you can go at about the same speed I just moved your leg, and then return it to the starting position.”

-

Mode of obtaining information:

Palpation: ASIS

Vision: ASIS opposite the moving LE

Judgment: Based on the information obtained visually, the examiner makes a decision if early lumbar motion (lumbar region is more flexible than the hip joint) occurs while the patient performs the LE movement and as operationally defined.

-

-

Lumbopelvic rotation with knee flexion in prone

-

Operational definition for lumbopelvic rotation

Hand placement: The examiner places a hand over the sacrum so that a line through the MCP joints is coincident with the long axis of the sacrum, and the long axis of the hand and sacrum are perpendicular to each other.

-

Criterion for significant degree of pelvic rotation:

Using the tips of the fingers of the hand as a visual reference for pelvic motion, 1/2 inch or greater of motion must occur relative to the starting position to be significant.

-

Criterion for pelvic rotation or anterior tilt < 90°:

Using the above noted criterion for significant degree of pelvic rotation or anterior tilt, the 1/2 inch or greater of motion occurs when the knee is flexed to less than or equal to 90 degrees

-

Criterion for pelvic rotation or anterior tilt > 90°:

Using the above noted criterion for significant degree of pelvic rotation or anterior tilt, the 1/2 inch or greater of motion occurs when the knee is flexed more than 90 degrees

-

Test procedure.

-

Starting position of the patient: The patient should be in the prone position with arms positioned at his or her side with the head relaxed and turned to either side, or in midline with a towel roll under the forehead, whichever is most comfortable for the patient. The patient’s hips should be positioned in neutral abduction/adduction and neutral rotation.

If unable to get both hips in neutral abduction/adduction, the examiner should abduct the LE that is not being tested and then position the tested LE in the neutral abduction/adduction.

If a pillow is placed under the trunk this should be recorded on the data sheet.

-

Starting position of examiner:

Side view and above, pelvic level.

The examiner should stand on the opposite side of the tested extremity.

-

Procedure:

The examiner moves each LE passively through the available ROM.

The examiner then has the patient perform active knee flexion in prone separately with each LE.

The examiner places one hand across the sacrum as a visual cue for pelvic movement; the hand is positioned so that the MCP joints are in line with the long axis of the sacrum, and the long axis of the hand and sacrum are perpendicular.

-

Instructions to the patient:

“Bend your (side) knee just as I did then return your leg to the starting position.”

Mode of obtaining information: Visual inspection.

-

Judgment: Based on the information obtained visually the examiner makes a decision about the presence of early lumbar motion (lumbar region is more flexible than the hip joint) as operationally defined.

The examiner decides if early lumbar motion is displayed as (a) pelvic rotation with knee flexion, (b) anterior tilt with knee flexion, or (c) both signs which is indicated by marking both pelvic rotation and anterior tilt.

-

-

-

Lumbopelvic rotation with hip lateral rotation in prone

***Please note this is the information for lumbopelvic motion with hip rotation in general; the definitions are not separated by medial/lateral rotation

-

Operational definition for lumbopelvic rotation

Hand placement: The examiner places a hand over the sacrum so that a line through the MCP joints is coincident with the long axis of the sacrum, and the long axis of the hand and sacrum are perpendicular to each other.

-

Criterion for significant degree of pelvic rotation:

Using the fingertips of the hand as a visual reference for pelvic motion, 1/2 inch or greater of motion must occur relative to the starting position to be significant. Pelvic rotation would most typically occur with hip lateral rotation.

-

Criterion for pelvic rotation in the 1st 50%:

Using the above noted criterion for significant degree of pelvic rotation, the 1/2 inch or greater of motion occurs within the 1st 50% of the hip ROM

-

Criterion for pelvic rotation in the 2nd 50%:

Using the above noted criterion for significant degree of pelvic rotation, the 1/2 inch or greater of motion occurs within the 2nd 50% of the hip ROM

-

Test procedure

Starting position of the patient: The patient should be in the prone position with arms positioned at his or her side with the head relaxed and turned to either side, or in midline with a towel roll under the forehead, whichever is most comfortable for the patient. The patient’s hips should be positioned in neutral abduction/adduction and neutral rotation.

-

Starting position of the examiner:

Side view and above, pelvic level.

The examiner should stand on the side opposite of the tested extremity.

-

Procedure:

The examiner passively moves each LE through the available ROM.

The examiner then places his or her hand across the sacrum as a visual cue for pelvic movement. The hand is positioned so that the MCP joints are in line with the long axis of the sacrum, and the long axis of the hand and sacrum are perpendicular.

The examiner then has the patient actively move each hip through lateral rotation. The test is repeated as the patient actively moves each hip through medial rotation.

-

Instructions to the patient:

“Easily bend your (side) knee up, and then move your foot all the way in (lateral rotation) at the same speed I just moved your leg passively; (repeat with opposite LE).”

“Easily bend your (side) knee up, and then move your foot all the way out (medial rotation) at the same speed I just moved your leg passively; (repeat with opposite LE).”

Mode of obtaining information: Visual inspection.

-

Judgment: Based on the information obtained visually the examiner makes a decision about the presence of early lumbar motion (lumbar region is more flexible than the hip joint) or asymmetrical pelvic rotation as operationally defined. Asymmetrical pelvic rotation:

The examiner decides if early lumbar motion is displayed as (a) pelvic rotation with knee flexion, b) anterior tilt with knee flexion, or (c) both signs which is indicated by marking both pelvic rotation and anterior tilt.

-

Lateral pelvic tilt with rocking backward in quadruped

-

Operational definition of lateral pelvic tilt

Hand placement: hands are placed on the iliac crest bilaterally

-

Criterion for significant degree of pelvic tilt:

Using the thumbs of the hands around the iliac crests as a visual reference for pelvic motion, 1/2 inch or greater of motion must occur

-

Criterion for pelvic tilt in the 1st 50%:

Using the above noted criterion for significant degree of pelvic tilt, the 1/2 inch or greater of motion occurs within the 1st 50% of the backward motion

-

Criterion for pelvic tilt in the 2nd 50%:

Using the above noted criterion for significant degree of pelvic tilt, the 1/2 inch or greater of motion occurs within the 2nd 50% of the backward motion; or there is a 1/2 inch or greater difference in the iliac crest height when the patient has completed the rocking backward movement

-

Test procedures

Starting position of the patient: The patient should be in, or as close as possible to, the ideal alignment before rocking back (i.e. corrected quadruped starting alignment).

-

Starting position of the examiner:

The examiner is at the foot of the table and above the pelvis.

This will require the examiner to use a foot stool or climb up on the table to obtain the appropriate perspective.

It is essential that the examiner is above the pelvis.

-

Procedure:

-

The patient will perform this movement 2 times.

The examiner will be in the starting position described above for the first movement (judgment of pelvic rotation or pelvic lateral tilt).

The examiner will then move to the side view for the final movement (judgment of lumbar flexion).

-

-

Instructions to the patient:

“From the quadruped position, I want you to rock back so you are sitting on your heels. Keep your hands in the starting position.”

-

Mode of obtaining information: Visual inspection.

Palpation: The examiner places one hand each around the iliac crests and aligns the thumbs so they are in the same plane and parallel to the posterior aspect of the iliac crests.

Vision: Hands around the iliac crests and thumb alignment.

Judgment: Based on the information obtained visually, the examiner makes a decision about the presence of whether pelvic tilt has occurred as operationally defined. The judgment is based on 2 rocking motions; pelvic tilt must occur with two rocking motions in a row for the examiner to respond “yes” to this item.

-

-

Pelvic rotation with rocking back in quadruped

-

Operational definition

***There is not an operational definition for pelvic rotation with rocking back in quadruped

-

Test procedure

Starting position of the patient: The patient should be in, or as close as possible to, the ideal alignment before rocking back (i.e. corrected quadruped starting alignment).

-

Starting position of the examiner:

The examiner is at the foot of the table and above the pelvis.

This will require the examiner to use a foot stool or climb up on the table to obtain the appropriate perspective.

It is essential that the examiner is above the pelvis.

-

Procedure:

-

The patient will perform this movement 2 times.

The examiner will be in the starting position described above for the first movement (judgment of pelvic rotation or pelvic lateral tilt).

The examiner will then move to the side view for the final movement (judgment of lumbar flexion).

-

-

Instructions to the patient:

“From the quadruped position, I want you to rock back so you are sitting on your heels.”

-

Mode of obtaining information: Visual inspection.

Palpation: The examiner places one hand each around the iliac crests and aligns the thumbs so they are in the same plane and parallel to the posterior aspect of the iliac crests.

Vision: Hands around the iliac crests and thumb alignment.

Judgment: The examiner determines whether pelvic rotation has occurred as operationally defined. The judgment is based on 2 rocking motions; pelvic rotation must occur with two rocking motions in a row for the examiner to respond “yes” to this item.

-

-

Lumbar rotation with single arm lift in quadruped

***Please note this is the information for asymmetrical rotation of the lumbar region with arm lifting in quadruped

-

Operational definition for asymmetrical rotation of lumbar region with arm lifting in quadruped

In the corrected starting alignment of quadruped, rotation of the lumbar vertebrae occurs with arm lifting on one side but not the other, or is greater, according to the criterion, with arm lifting on one side than the other.

Hand placement: The examiner places one hand each on the tissue 2 inches to either side of the lumbar region.

-

Criterion for significant degree of difference in degree of rotation occurring with movement of one UE vs. the other:

Using the hands as a visual reference for presumed spinal motion, 1/2 inch or greater difference in movement of the hands must occur with arm lifting on one side vs. the other to be significant. The amount of hand movement is relative to starting position.

-

Test procedure

Starting position of patient: The patient should be in, or as close as possible to, the ideal alignment before lifting his or her UE (i.e. corrected quadruped starting alignment).

-

Starting position of the examiner:

The examiner is at the foot of the table and above the pelvis.

This will require the examiner to use a foot stool or climb up on the table to obtain the appropriate perspective.

It is essential that the examiner is above the pelvis.

-

Instructions to the patient:

“Easily lift your (side) arm up and out straight in front of you so it is parallel to the table, then return it to the starting position.”

Mode of obtaining information: Visual inspection.

Judgment: Based on the information obtained visually the examiner makes a decision about the presence of rotation of the lumbar region as operationally defined.

Footnotes

SPSS Inc, 233 S Wacker Dr, 11th Fl, Chicago, IL 60606.

Material from this manuscript was presented in poster format at the 5th Interdisciplinary World Congress on Low Back and Pelvic Pain in Melbourne, Australia, November 11, 2004 and the National Clinical and Translational Sciences Predoctoral Programs Meeting in Rochester, MN, May 6, 2013.

We certify that no party having a direct interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on us or on any organization with which we are associated, and we certify that all financial and material support for this research and work are clearly identified in the title page of the manuscript.

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical devices.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Frymoyer JW. Back pain and sciatica. New Eng J Med. 1988;318(5):291–300. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198802043180506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo X, Pietrobon R, Sun SX, Liu GG, Hey L. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004;29(1):79–86. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000105527.13866.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chard MD, Lachmann SM. Racquet sports--patterns of injury presenting to a sports injury clinic. Br J Sports Med. 1987;21(4):150–3. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.21.4.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg A, Moore JS. Epidemiology of low-back pain in industry. Occup Med. 1992;7(4):593–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoogendoorn WE, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, Ariens GA, van MW, Bouter LM. High physical work load and low job satisfaction increase the risk of sickness absence due to low back pain: results of a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59(5):323–8. doi: 10.1136/oem.59.5.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosea TM, Gatt CJ., Jr Back pain in golf. Clin Sports Med. 1996;15(1):37–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marras WS, Lavender SA, Leurgans SE, et al. The role of dynamic three-dimensional trunk motion in occupationally-related low back disorders. The effects of workplace factors, trunk position, and trunk motion characteristics on risk of injury. Spine. 1993;18(5):617–28. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199304000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarroll JR. The frequency of golf injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1996;15(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Punnett L, Fine LJ, Keyserling WM, Herrin GD, Chaffin DB. Back disorders and nonneutral trunk postures of automobile assembly workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1991;17(5):337–46. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sward L, Hellstrom M, Jacobsson B, Peterson L. Back pain and radiologic changes in the thoraco-lumbar spine of athletes. Spine. 1990;15(2):124–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199002000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Dillen LR, Sahrmann SA, Caldwell CA, McDonnell MK, Bloom N, Norton BJ. Trunk rotation-related impairments in people with low back pain who participated in 2 different types of leisure activities: a secondary analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(2):58–71. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.36.2.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. 1. St. Louis: Mosby, Inc; 2002. Movement impairment syndromes of the lumbar spine; pp. 51–118. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman SL, Johnson MB, Zou D, Harris-Hayes M, Van Dillen LR. Effect of classification-specific treatment on lumbopelvic motion during hip rotation in people with low back pain. Man Ther. 2011;16(4):344–50. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gombatto SP, Collins DR, Sahrmann SA, Engsberg JR, Van Dillen LR. Gender differences in pattern of hip and lumbopelvic rotation in people with low back pain. Clin Biomech. 2006;21(3):263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholtes SA, Gombatto SP, Van Dillen LR. Differences in lumbopelvic motion between people with and people without low back pain during two lower limb movement tests. Clin Biomech. 2009;24(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norton BJ, Sahrmann SA, Van Dillen FL. Differences in measurements of lumbar curvature related to gender and low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(9):524–34. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2004.34.9.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gombatto SP, Collins DR, Sahrmann SA, Engsberg JR, Van Dillen LR. Patterns of lumbar region movement during trunk lateral bending in 2 subgroups of people with low back pain. Phys Ther. 2007;87(4):441–54. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20050370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Dillen LR, Gombatto SP, Collins DR, Engsberg JR, Sahrmann SA. Symmetry of timing of hip and lumbopelvic rotation motion in 2 different subgroups of people with low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(3):351–60. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGill SM. The biomechanics of low back injury: implications on current practice in industry and the clinic. J Biomech. 1997;30(5):465–75. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(96)00172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholtes SA, Norton BJ, Lang CE, Van Dillen LR. The effect of within-session instruction on lumbopelvic motion during a lower limb movement in people with and people without low back pain. Man Ther. 2010;15(5):496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman SL, Johnson MB, Zou D, Van Dillen LR. Sex differences in lumbopelvic movement patterns during hip medial rotation in people with chronic low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(7):1053–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman SL, Johnson MB, Zou D, Van Dillen LR. Gender differences in modifying lumbopelvic motion during hip medial rotation in people with low back pain. Rehabil Res Pract. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/635312. Article ID 635312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Dillen LR, Sahrmann SA, Norton BJ. Kinesiopathologic Model and Low Back Pain. In: Hodges PW, Cholewicki J, van Dieen JH, Herbert R, editors. Spinal Control: The Rehabilitation of Back Pain. Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2012. pp. 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Dillen LR, Sahrmann SA, Norton BJ, et al. Reliability of physical examination items used for classification of patients with low back pain. Phys Ther. 1998;78(9):979–88. doi: 10.1093/ptj/78.9.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vad VB, Bhat AL, Basrai D, Gebeh A, Aspergren DD, Andrews JR. Low back pain in professional golfers: the role of associated hip and low back range-of-motion deficits. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(2):494–7. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Von Korff M. Studying the natural history of back pain. Spine. 1994;19(18 Suppl):2041S–6S. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199409151-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Delayed postural contraction of transversus abdominis in low back pain associated with movement of the lower limb. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11(1):46–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36(5):936–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O'Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiother. 1980;66(8):271–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Videman T, Sarna S, Battie MC, et al. The long-term effects of physical loading and exercise lifestyles on back-related symptoms, disability, and spinal pathology among men. Spine. 1995;20(6):699–709. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199503150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Dillen LR, Sahrmann SA, Norton BJ, Caldwell CA, McDonnell MK, Bloom N. The effect of modifying patient-preferred spinal movement and alignment during symptom testing in patients with low back pain: a preliminary report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(3):313–22. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoogendoorn WE, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, et al. Flexion and rotation of the trunk and lifting at work are risk factors for low back pain: results of a prospective cohort study. Spine. 2000;25(23):3087–92. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marras WS, Lavender SA, Ferguson SA, Splittstoesser RE, Yang G. Quantitative dynamic measures of physical exposure predict low back functional impairment. Spine. 2010;35(8):914–23. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ce1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heneweer H, Staes F, Aufdemkampe G, van Rijn M, Vanhees L. Physical activity and low back pain: a systematic review of recent literature. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(6):826–45. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1680-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoogendoorn WE, van Poppel MN, Bongers PM, Koes B, Bouter LM. Physical load during work and leisure time as risk factors for back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999;25(5):387–403. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baranto A, Hellstrom M, Cederlund CG, Nyman R, Sward L. Back pain and MRI changes in the thoraco-lumbar spine of top athletes in four different sports: a 15-year follow-up study. Knee Surg Sports Tr A. 2009;17(9):1125–34. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0767-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alricsson M, Werner S. Young elite cross-country skiers and low back pain-A 5- year study. Phys Ther Sport. 2006;7(4):181–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sward L. The thoracolumbar spine in young elite athletes. Current concepts on the effects of physical training. Sports Med. 1992;13(5):357–64. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199213050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vad VB, Gebeh A, Dines D, Altchek D, Norris B. Hip and shoulder internal rotation range of motion deficits in professional tennis players. J Sci Med Sport. 2003;6(1):71–5. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(03)80010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray E, Birley E, Twycross-Lewis R, Morrissey D. The relationship between hip rotation range of movement and low back pain prevalence in amateur golfers: an observational study. Phys Ther Sport. 2009;10(4):131–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chimenti RL, Scholtes SA, Van Dillen LR. Activity characteristics and movement patterns in people with and people without chronic or recurrent low back pain who participate in rotation-related sports. J Sport Rehabil. 2013;22(3):161–9. doi: 10.1123/jsr.22.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]