Abstract

Purpose

To report a case of Coats’ disease in which spontaneous reattachment occurred after total retinal detachment.

Patient and Methods

A young boy (patient age: 4 years and 11 months) presented with leukocoria in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination revealed total retinal detachment with abnormal retinal blood vessels and subretinal exudation just behind the lens. Computed tomography imaging showed no solid mass lesion in the intraocular space. Secondary total retinal detachment as a complication of Coats’ disease was diagnosed. No light perception was detected, so we determined that surgical treatment was not indicated.

Results

Four months after the initial diagnosis, the retina showed complete reattachment with a large amount of subretinal hard exudate. Visual acuity remained unchanged, with no light perception.

Conclusions

We speculate that the spontaneous retinal reattachment in the present case was caused by the decreased permeability of the abnormal retinal vessels and the good functional effect of the retinal pigment epithelium.

Key Words: Coats’ disease, Retinal detachment, Spontaneous reattachment of the retina, Subretinal exudate

Introduction

Coats’ disease is a congenital abnormality of the retinal vessels with telangiectasia and is characterized by increased vascular permeability that results in the accumulation of subretinal exudate [1]. Coats’ disease is unilateral and occurs predominantly in school-age boys. Along with the progression of the characteristic subretinal exudates in Coats’ disease, retinal detachment and neovascular glaucoma can also occur, thus leading to blindness. Depending on the stage of the disease, a treatment such as photocoagulation is necessary to preserve visual function. Although spontaneous regression of Coats’ disease has occasionally been reported, spontaneous reattachment after total retinal detachment is extremely rare. In the current study, we present the case of a young boy with Coats’ disease who showed spontaneous reattachment on follow-up observation alone after total retinal detachment.

Case Report

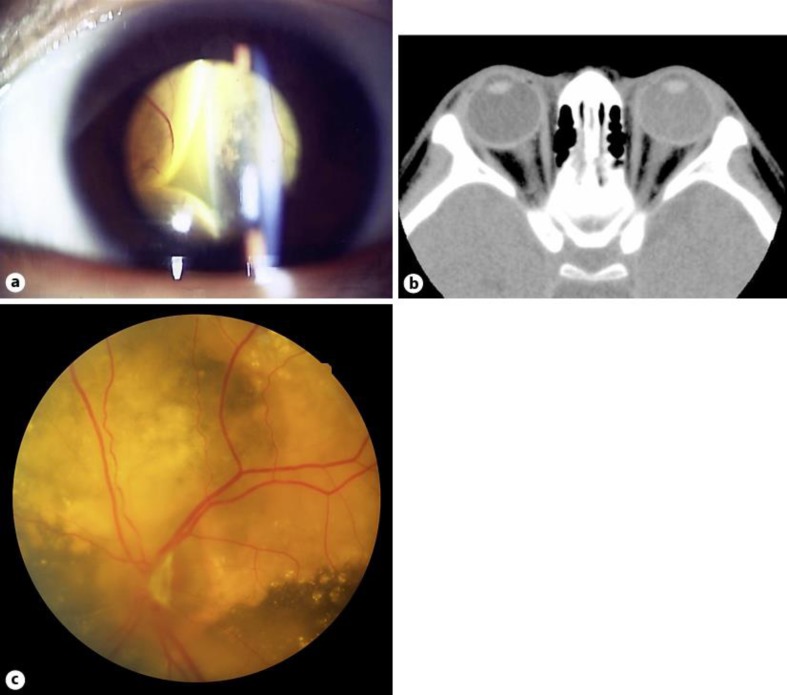

This case report involved a young boy (patient age: 4 years and 11 months) who presented with the primary complaint of visual disturbance in his left eye. The boy's mother had noticed leukocoria (an abnormal white reflection from the retina) in his left eye, and he was subsequently referred to our hospital by a local physician. Investigation of the patient's past medical history, as well as that of his family, revealed nothing of note. Upon initial examination, visual acuity in his right eye was 20/20, yet no light perception was detected in his left eye. The patient's intraocular pressure was 11 mm Hg (OD) and 15 mm Hg (OS). Although the lens in his left eye was transparent, slit-lamp examination revealed bullous retinal detachment just behind the lens (fig. 1a). Abnormal retinal vessels with telangiectasia and microaneurysms were present, as well as the deposition of a large amount of subretinal hard exudate. There were no abnormalities in the patient's right eye.

Fig. 1.

a Photograph of the anterior segment of the left eye of a young male patient at the initial examination. Bullous retinal detachment is evident just behind the lens. b Computed tomography imaging of the patient's left eye. There were no findings suggesting a solid mass or any calcification. c Fundus photography of the patient's left eye at 4 months after the initial examination. Although many subretinal hard exudates are present, the retina has completely reattached.

Further evaluation of the patient's left eye was performed to rule out late-onset retinoblastoma. An examination by ultrasound revealed retinal detachment, but no other findings suggesting a mass. In addition, orbital computed tomography imaging revealed no solid masses or calcification (fig. 1b). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed as having Coats’ disease complicated with total retinal detachment in the left eye. Surgical treatment was not indicated, due to the absence of light perception. Four months after the initial examination, a follow-up examination revealed that the retina had spontaneously and completely reattached despite the deposition of numerous subretinal hard exudates (fig. 1c). An ultrasonic B-mode scanning image also indicated complete reattachment of the retina. However, light perception was still absent. At present, approximately 10 months after the spontaneous reattachment, there has been no recurrence of retinal detachment.

Discussion

Shields et al. [2] classified Coats’ disease into 5 stages and proposed a specific treatment for each stage. In stage 1 (telangiectasia only without exudative changes), follow-up observation is recommended. In stage 2 (telangiectasia and exudative changes) and stage 3A (subtotal exudative retinal detachment), retinal photocoagulation or retinal cryopexy of the abnormal retinal vessels is recommended. In stage 3B (total exudative retinal detachment), surgical treatment (e.g., subretinal fluid drainage, scleral buckling, or vitrectomy) together with retinal photocoagulation or retinal cryopexy is recommended. More recently, the new treatment of intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents has been reported to be effective [3].

A few studies have reported on spontaneous regression in Coats’ disease; however, it is believed that this phenomenon tends to occur in relatively older patients (i.e., between 8 and 28 years of age) [4, 5]. However, Ozdek et al. [6] reported spontaneous regression of Coats’ disease in both a 3-year-old and a 4-year-old child, and emphasized that spontaneous regression might also occur in younger children. At present, consensus is still lacking on the mechanisms underlying spontaneous regression in Coats’ disease.

In our patient with total retinal detachment, we postulate that the mechanism of spontaneous reattachment involved the following factors. First, vascular permeability of the abnormal retinal vessels seemed to decrease by some mechanism during the follow-up observation, which probably led to improvements in the exudative changes. In retinal vessels, the tight junctions between vascular endothelial cells usually prevent the exudation of plasma components. This barrier function is reportedly disrupted in abnormal retinal vessels, thus leading to exudation of plasma components [7]. VEGF is a potent vascular permeability-enhancing factor that is released by retinal ischemia, but when the retinal detachment persists over a long period, the detached retina itself becomes thinner and VEGF production may subsequently decrease, potentially leading to reductions in vascular permeability. Fluorescein angiography could not be performed in the present case, because the patient was 4 years old and full cooperation could not be obtained.

Second, since retinal pigment epithelial function is good in younger patients, this vigorous pumping action may overcome the exudative changes, subsequently promoting the elimination of subretinal exudate. In addition, although various biological substances from abnormal retinal vessels in Coats’ disease can cause vitreous gel contraction, radical reactions due to these substances promote vitreous liquefaction, thus reducing the vitreoretinal traction. In fact, in our patient, after the spontaneous reattachment of the retina, considerable liquefaction of the vitreous gel was evident considering the patient's age. Since optical coherence tomography could not be performed in this case, we were unable to evaluate the vitreoretinal traction and liquefaction of the vitreous gel in detail. However, the stereoscopic fundus examination using binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy roughly indicated these clinical findings.

In conclusion, patients with advanced Coats’ disease who experience total retinal detachment are usually thought to require early treatment with scleral buckling or vitrectomy, together with subretinal fluid drainage and transscleral cryotherapy [7, 8]. However, in patients with no light perception, such as the patient in the present study, careful follow-up observation in the hope of spontaneous reattachment is an option. Nevertheless, it is important that patients with some hope for improved visual acuity should be treated appropriately and at an appropriate time without an unnecessarily long follow-up observation.

Statement of Ethics

This case report has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka Medical College.

Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank John Bush for editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Coats G. Forms of retinal disease with massive exudation. R London Ophthalm Hosp Rep. 1908;17:440–525. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields JA, Shields CL, Honavar SG, Demirci H, Cater J. Classification and management of Coats disease: the 2000 Proctor Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:572–583. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)00896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaillard MC, Mataftsi A, Balmer A, Houghton S, Munier FL. Ranibizumab in the management of advanced Coats disease stages 3B and 4: long-term outcomes. Retina. 2014;34:2275–2281. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deutsch TA, Rabb MF, Jampol LM. Spontaneous regression of retinal lesions in Coats’ disease. Can J Ophthalmol. 1982;17:169–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe JD, Hubbard GB., 3rd Spontaneous regression of subretinal exudate in coats disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1208–1209. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.8.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozdek SC, Erdinc T, Kagnici B. Spontaneous regression in two unusual cases of advanced Coats’ disease. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2010;26:1–4. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20100318-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridley ME, Shields JA, Brown GC, Tasman W. Coats’ disease. Evaluation of management. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1381–1387. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt-Erfurth U, Lucke K. Vitreoretinal surgery in advanced Coat's disease. Ger J Ophthalmol. 1995;4:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]