Abstract

Objective

To compare the interlaminar and transforaminal block techniques with regard to the state of pain and presence or absence of complications.

Method

This was a randomized double-blind prospective study of descriptive and comparative nature, on 40 patients of both sexes who presented lumbar sciatic pain due to central-lateral or foraminal disk hernias. The patients had failed to respond to 20 physiotherapy sessions, but did not present instability, as diagnosed in dynamic radiographic examinations. The type of block to be used was determined by means of a draw: transforaminal (group 1; 20 patients) or interlaminar (group 2; 20 patients).

Results

Forty patients were evaluated (17 males), with a mean age of 49 years. There was a significant improvement in the state of pain in all patients who underwent radicular block using both techniques, although the transforaminal technique presented better results than the interlaminar technique.

Conclusion

Both techniques were effective for pain relief and presented low complication rates, but the transforaminal technique was more effective than the interlaminar technique.

Keywords: Nerve block, Intervertebral disk displacement, Lumbar pain

Resumo

Objetivo

Comparar a técnica de bloqueio interlaminar com a de bloqueio transforaminal, quanto ao quadro álgico e à presença ou não de complicações.

Método

Estudo prospectivo, de caráter descritivo e comparativo, duplo-cego e randomizado, em que são sujeitos 40 pacientes, de ambos os sexos, portadores de lombociatalgia por hérnia de disco, do tipo centro-lateral ou foraminal, sem resposta a 20 sessões de fisioterapia e sem instabilidade, diagnosticada em exame de radiografia dinâmica. O tipo de bloqueio, transforaminal (grupo 1) ou interlaminar (grupo 2), a ser feito foi determinado por meio de sorteio e constituiu 20 pacientes do grupo 1 e 20 do grupo 2.

Resultados

Foram avaliados 40 pacientes, 17 do sexo masculino, média de 49 anos, nos quais houve melhoria significativa do quadro álgico em todos os submetidos ao bloqueio radicular em ambas as técnicas, embora a técnica transforaminal apresentasse melhores resultados quando comparada com a interlaminar.

Conclusão

Ambas as técnicas são eficazes no alívio da dor e apresentam baixa taxa de complicação, mas a transforaminal foi mais eficaz do que a interlaminar.

Palavras-chave: Bloqueio nervoso, Deslocamento do disco intervertebral, Dor lombar

Introduction

Lumbar disk hernia consists of displacement of the pulpous nucleus contained in the intervertebral disk through the fibrous ring. This displacement may lead to compression and irritation of the lumbar nerve roots and dural sac, which are characterized clinically by the pain known as sciatic pain.1

The etiology of sciatic pain is multifactorial. It can be caused by mechanical compression of the intervertebral disk and by the release of inflammatory and nociceptive mediators coming from the pulpous nucleus.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 It has been estimated that 2–3% of the population has lumbar disk hernias, with prevalence of 4.8% among men and 2.5% among women over the age of 35 years. Furthermore, it is the commonest diagnosis among degenerative alterations of the lumbar spine and the main cause of surgery.1

The initial treatment for disk hernia in most cases is conservative. Surgical treatment is exceptional and is reserved only for cases of lack of success from appropriate conservative treatment, progressive neurological deficit or cauda equina syndrome.1, 9 Among the various techniques that have been described in the literature, minimally invasive surgical procedures are now valued more highly because of their lower tissue aggression, shorter hospital stay, lower anesthetic risk and earlier return to work activities.1, 8, 9, 10

Root block is a good option among the minimally invasive techniques for treating lumbar disk hernia. This makes it possible to reduce the inflammatory response, improve the state of pain, reduce the consumption of analgesics, maintain work activities and eliminate the need for surgery, among most individuals.8, 11, 12, 13

For patients who are refractory to appropriate conservative treatment, in an attempt to postpone or even to avoid surgery, root block can be indicated. This can be done using interlaminar and transforaminal techniques, or caudally (via the sacral hiatus).1, 14, 15

However, only a few studies in the literature have compared the interlaminar and transforaminal techniques with a view to determining which of these is safer and more effective. We conducted the present study with the aim of clarifying these doubts, so as to make a significant contribution toward alleviating the symptoms caused by disk hernias.

Method

Forty patients were evaluated through a double-blind randomized prospective study.

The sample selection took into consideration the following inclusion criteria: the patients needed to present lumbar sciatic pain secondary to disk hernia, with posterolateral, foraminal or extraforaminal location, which could be either limited to that location or extend beyond it, without any response to 20 physiotherapy sessions, and without any instability diagnosed in dynamic radiographic examinations of the lumbar spine. We took instability to be situations of vertebral plateau angles greater than 18° and excursions of more than 3 mm on dynamic lumbar radiographs in lateral view.16

Patients were excluded if they presented lumbar sciatic pain with causes other than disk hernia, or if their pain responded to conservative treatment consisting of 20 physiotherapy sessions, or if they presented dynamic instability on radiographs.

A visual analog scale (VAS) was applied to all the patients before and after receiving the block.4, 6, 17 The decision on which block technique would be used was reached by means of a draw. In this, the number 1 represented the transforaminal technique and 2, the interlaminar technique.

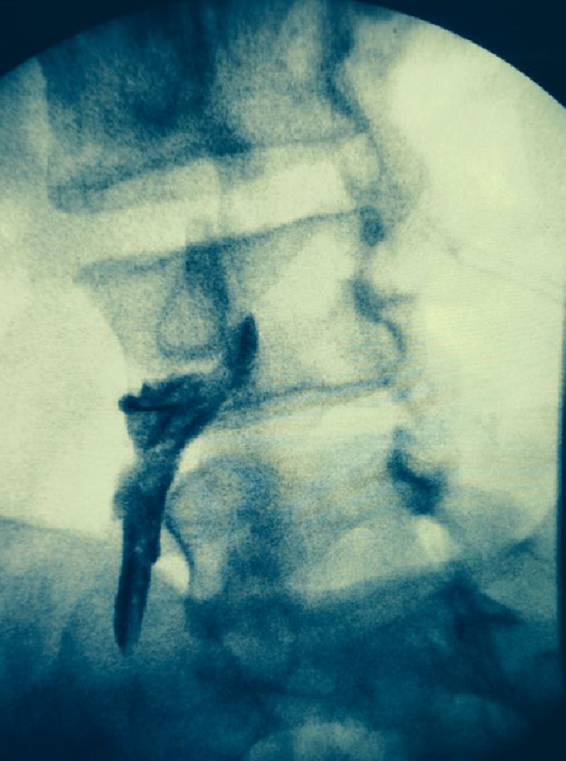

The block using the transforaminal technique was applied with the patients positioned in ventral decubitus, with a pillow under the abdomen. All the patients received only one level of block. We used a fluoroscopic device to obtain an anteroposterior image and to be able to identify the desired level of the spine, followed by an oblique ipsilateral Scotty-dog view. The six o’clock position on the pedicle was marked out and this received an infiltration of 1% lidocaine using a needle of caliber 25 and 1.5 inches in length. A Tuohy needle of caliber 22 and 3.5 inches in length was directed towards the spine under intermittent fluoroscopic guidance in the neural foramen, such that the tip would rest in the triangle formed by the nerve root medially, the bone pedicle superiorly and the lateral margin of the foramen laterally. The position of the needle was confirmed through observation of the flow of 2 mL of the contrast medium ioversol (68%) with 320 mg/mL of concentrated iodine, injected into each level. Once the placement had been confirmed, a solution of total volume 10 mL, consisting of 3 mL of betamethasone phosphate (40 mg/mL), 2 mL of 0.25% neo-bupivacaine and 5 mL of distilled water, was injected (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).3, 5, 6, 12, 18

Fig. 1.

Transforaminal block. Image obtained via fluoroscopy.

Fig. 2.

Transforaminal block (in lateral view, for adequate viewing of the contrast distribution). Image obtained via fluoroscopy.

In the patients who underwent the interlaminar technique, we followed positioning similar to that of the transforaminal technique. The upper edge of the ipsilateral inferior lamina was marked out and the skin and tissue covering the target point were infiltrated. Loss of resistance is the main sign of entry into the epidural space. After inserting the needle into the peridural space, lateral fluoroscopic viewing was set up in order to ensure that the tip of the needle would rest in the posterior epidural space. Following this, the same volumes of the same medications as described for the transforaminal technique were injected (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Interlaminar block. Image obtained via fluoroscopy.

Fig. 4.

Interlaminar block (in lateral view, for adequate viewing of the contrast distribution). Image obtained via fluoroscopy.

After the block had been applied, the patient made use of the same analgesic medication in the hospital and then after discharge from the hospital. The preferred medication was dipyrone: 500 mg every six hours in the eventuality of pain. Only 90 days after receiving the block were the patients referred for motor physiotherapy. The VAS was applied immediately after the patients had received the analgesic block, and then 24 h and 7, 21 and 90 days afterward. Complications such as headache, sudden pain, lumbalgia, temporary motor deficit, permanent motor deficit and extravasation of fluid were evaluated clinically and described in specific medical files.19, 20

The evaluators before and after the operation were kept unaware of which technique had been applied to each patient and they acted independently with regard to the post-block follow-up.

We used statistical analysis with parametric tests to evaluate data with normal distribution, and this was done in analyzing the results from the transforaminal technique. On the other hand, in cases in which the distribution of probabilities was not normal, we used nonparametric tests. This was used in analyzing the results from the interlaminar technique and for comparing the results between the two techniques. To estimate post-block means, a new dataset was generated using the means from the results at each measurement time, for each patient.

Results

Among the 40 patients analyzed, 17 were male and the mean age was 49.45 years. Twenty underwent the transforaminal technique and twenty, the interlaminar technique. In the group with interlaminar block, the mean age was 50.05 years and, out of the 20 patients, 10 were male (50%) and 10 were female (50%). In the group with transforaminal block, the mean age was 48.85 years, with seven male patients (35%) and 13 female patients (65%).

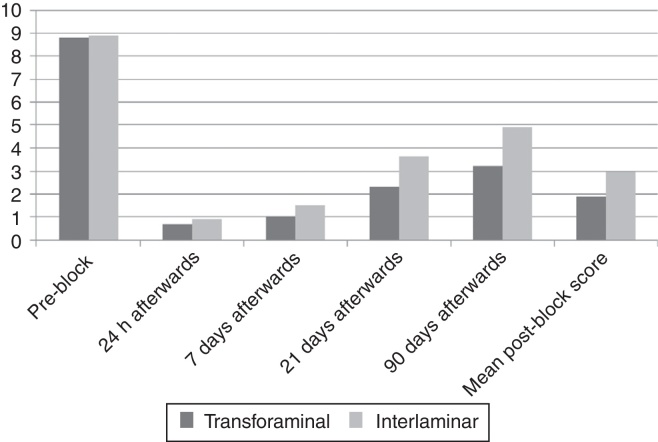

In comparing the pre-block VAS values with the times of 24 h and 7, 21 and 90 days afterwards, in relation to both techniques, we found statistically significant results (p < 0.05) at all times, independent of the technique applied, as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the mean VAS scores between the different measurement times, for the two techniques used.

In analyzing the mean VAS scores at specific times, we observed that the transforaminal technique presented better results at all the times analyzed, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the mean VAS score results between the techniques, for each measurement time.

| Pre-block | 24 h afterwards | 7 days afterwards | 21 days afterwards | 90 days afterwards | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transforaminal technique | 8.81 | 0.71 | 1.05 | 2.33 | 3.84 |

| Interlaminar technique | 8.89 | 0.89 | 1.53 | 3.65 | 4.88 |

| p value | 0.774 | 0.492 | 0.256 | 0.022 | 0.195 |

Mann–Whitney test (comparison between two non-normal independent samples).

In analyzing the mean pre-block VAS score and the mean final post-block VAS score between the techniques, a statistical difference was observed between them, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean VAS scores – overall before and after block.

| Mean pre-block VAS score | Mean post-block VAS score | p value |

|---|---|---|

| 8.85 | 2.32 | 0.000 |

p, statistical significance.

Wilcoxon test (comparison of two dependent samples).

In comparing the mean final post-block VAS score between the transforaminal and interlaminar techniques, we observed that there was a statistically significant higher pain level in the transforaminal technique, as demonstrated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mean post-block VAS scores, according to technique.

| Pre-block | After transforaminal technique | After interlaminar technique | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8.85 | 1.97 | 2.71 | 0.027 |

p, statistical significance.

Mann–Whitney test (comparison between two non-normal independent samples).

In relation to the various complications that existed, we present here only two: one of lumbalgia in the group with the transforaminal technique and one of headache in the interlaminar group. In the patient with headache, there was no puncturing of the dura mater during the procedure.

Discussion

Root block may be a good propaedeutic method for alleviating the symptoms and reestablishing the quality of life of patients with disk hernias.

Among the various techniques that have been described, the interlaminar, transforaminal and caudal methods are the ones most frequently used. In terms of efficacy, several studies have demonstrated unequivocally that epidural injections of steroids are effective for the intended purpose, although the benefits are only of short to medium duration.6, 11, 12, 21

In our study, we found that there was a significant improvement in the state of pain after the block was administered, independent of the type of technique used. Most studies have indicated that the advantages of the interlaminar technique are its greater safety and lower lumbar discomfort,22, 23 whereas the transforaminal technique is more effective for reducing pain over the long term.13, 14, 15, 18, 22, 23, 24

In relation to the state of pain, we observed that although improvements occurred through both of the techniques analyzed, the transforaminal technique was more effective for reducing the state of pain, especially after the 21st post-block day, and this improvement persisted until the end of the study.

Regarding the safety of the procedures, both of the techniques were seen to be safe in our study and there were no important complications.

We judge that root block is a safe option, with good results regarding alleviation of sciatic pain caused by disk hernias, for a moderate length of time.

Conclusion

The transforaminal block technique was shown to be safer and more effective for treating sciatic pain secondary to lumbar disk hernia than the interlaminar technique.

Funding

Science and Technology Support Fund of Vitória (FACITEC).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Work developed at Hospital da Santa Casa de Misericórdia, Vitória, ES, Brazil.

References

- 1.Vialle L.R., Vialle E.M., Henao J.E.S., Giraldo G. Hérnia discal lombar. Rev Bras Ortop. 2010;45(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30211-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sociedade Brasileira de Ortopedia e Traumatologia, Sociedade Brasileira de Neurofisiologia Clínica, Federação Brasileira das Associações de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia, Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia, Colégio Brasileiro de Radiologia . Associação Médica Brasileira e Conselho Federal de Medicina; São Paulo: 2007. Hérnia Discal Lombar no Adulto Jovem [projeto diretrizes]http://www.projetodiretrizes.org.br/7_volume/29-hernia.sc.lom.adul.pdf Available in: [accessed on 15.12.12] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tachihara H., Sekiguchi M., Kikuchi S., Konno S. Do corticosteroids produce additional benefit in nerve root infiltration for lumbar disc herniation? Spine (Phila PA 1976) 2008;33(7):743–747. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181696132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Depalma M.J., Bhargava A., Slipman C.W. A critical appraisal of the evidence for selective nerve root injection in the treatment of lumbosacral radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(7):1477–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fish D.E., Lee P.C., Marcus D.B. The S1 “Scotty Dog”: report of a technique for S1 transforaminal epidural steroid injection. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(12):1730–1733. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karppinen J., Malmivaara A., Kurunlahti M., Kyllönen E., Pienimäki T., Nieminen P. Periradicular infiltration for sciatica: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila PA 1976) 2001;26(9):1059–1067. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200105010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar N., Gowda N. Cervical foraminal selective nerve root block: a “two-needle technique” with F results. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(4):576–584. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng L., Chaudhary N., Sell P. The efficacy of corticosteroids in periradicular infiltration for chronic radicular pain: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Spine (Phila PA 1976) 2005;30(8):857–862. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158878.93445.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Postacchini F. Management of herniation of the lumbar disc. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(4):567–576. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b4.10213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou R., Atlas S.J., Stanos S.P., Rosenquist R.W. Nonsurgical interventional therapies for low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society clinical practice guideline. Spine (Phila PA 1976) 2009;34(10):1078–1093. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a103b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sousa F.A., Colhado O.C. Bloqueio analgésico peridural lombar para tratamento de lombociatalgia discogênica: estudo clínico comparativo entre metilprednisolona e metilprednisolona associada à levobupivacaína. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2011;61(5):544–555. doi: 10.1016/S0034-7094(11)70065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sayegh F.E., Kenanidis E.I., Papavasiliou K.A., Potoupnis M.E., Kirkos J.M., Kapetanos J.A. Efficacy of steroid and nonsteroid caudal epidural injections for low back pain and sciatica: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Spine (Phila PA 1976) 2009;34(14):1441–1447. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a4804a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaufele M.K., Hatch L., Jones W. Interlaminar versus transforaminal epidural injections for the treatment of symptomatic lumbar intervertebral disc herniations. Pain Physician. 2006;9(4):361–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdi S., Datta S., Lucas L.F. Role of epidural steroids in the management of chronic spinal pain: a systematic review of effectiveness and complications. Pain Physician. 2005;8(1):127–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdi S., Datta S., Trescot A.M., Schultz D.M., Adlaka R., Atluri S.L. Epidural steroids in the management of chronic spinal pain: a systematic review. Pain Physician. 2007;10(1):185–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White A.A., Panjabi M.M. 2nd ed. Philadelphia; JB Lippincott: 1990. Clinical biomechanics of the spine. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murata Y., Kanaya K., Wada H., Wada K., Shiba M., Hatta S. Spine: affiliated society meeting abstracts (supplement 2011 ISSLS society meeting abstracts) 2011. The effect of L2 spinal nerve root infiltration for chronic low back pain: GP169 [Abstract]http://journals.lww.com/spinejournalabstracts/Fulltext/2011/10001/The_Effect_of_L2_Spinal_Nerve_Root_Infiltration.165.aspx Available from: [accessed on 15.12.12] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner B.K., Fraser R.D. Foraminal injection for lateral lumbar disc herniation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;79(5):804–807. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b5.7636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman B.S., Posecion L.W., Mallempati S., Bayazitoglu M. Complications and pitfalls of lumbar interlaminar and transforaminal epidural injections. Cur Rev Musc Med. 2008;1(3–4):212–222. doi: 10.1007/s12178-008-9035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karaman H., Kavak G.O., Tufek A., Yldrm Z.B. The complications of transforaminal lumbar epidural steroid injections. Spine (Phila PA 1976) 2011;36(13):819–824. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f32bae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stafford M.A., Peng P., Hill D.A. Sciatica: a review of history, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and the role of epidural steroid injection in management. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(4):46173. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasper J.F. Lumbar retrodiscal transforaminal injection. Pain Physician. 2007;10(3):501–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gharibo C.G., Varlotta G.P., Rhame E.E., Liu E.C., Bendo J.A., Perloff M.D. Interlaminar versus transforaminal epidural steroids for the treatment of subacute lumbar radicular pain: a randomized, blinded, prospective outcome study. Pain Physician. 2011;14(6):499–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderberg L., Säveland H., Annertz M. Distribution patterns of transforaminal injections in the cervical spine evaluated by multi-slice computed tomography. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(10):1465–1471. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]