Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma regarding healing, pain and hemostasis after total knee arthroplasty, by means of a blinded randomized controlled and blinded clinical study.

Methods

Forty patients who were going to undergo implantation of a total knee prosthesis were selected and randomized. In 20 of these patients, platelet-rich plasma was applied before the joint capsule was closed. The hemoglobin (mg/dL) and hematocrit (%) levels were assayed before the operation and 24 and 48 h afterwards. The Womac questionnaire and a verbal pain scale were applied and knee range of motion measurements were made up to the second postoperative month. The statistical analysis compared the results with the aim of determining whether there were any differences between the groups at each of the evaluation times.

Results

The hemoglobin (mg/dL) and hematocrit (%) measurements made before the operation and 24 and 48 h afterwards did not show any significant differences between the groups (p > 0.05). The Womac questionnaire and the range of motion measured before the operation and up to the first two months also did not show any statistical differences between the groups (p > 0.05). The pain evaluation using the verbal scale showed that there was an advantage for the group that received platelet-rich plasma, 24 h, 48 h, one week, three weeks and two months after the operation (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

In the manner in which the platelet-rich plasma was used, it was not shown to be effective for reducing bleeding or improving knee function after arthroplasty, in comparison with the controls. There was an advantage on the postoperative verbal pain scale.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, Knee, Transfusion, Platelet-rich plasma, Hemorrhage

Resumo

Objetivos

Avaliar, por meio de um estudo clínico, randomizado, controlado e cego, a eficácia do plasma rico em plaquetas na cicatrização, dor e hemostasia após artroplastia total do joelho.

Métodos

Foram selecionados 40 pacientes que seriam submetidos a prótese total do joelho e randomizados. Em 20 desses pacientes foi aplicado o plasma rico em plaquetas antes do fechamento da cápsula articular. Foram feitas dosagens de hemoglobina (mg/dL) e hematócrito (%) no pré-operatório, após 24 e 48 horas da cirurgia. Foram aplicados o questionário Womac e a escala verbal da dor e medidas as amplitudes de movimento do joelho até o segundo mês pós-operatório. A análise estatística comparou os resultados a fim de comprovar haver diferença entre os grupos em cada um dos momentos da avaliação.

Resultados

Medidas do valor da hemoglobina (mg/dL) e hematócrito (%) feitas no pré-operatório, após 24 e 48 horas da cirurgia, não mostraram diferenças significativas entre os grupos (p > 0,05). O questionário Womac e a amplitude de movimento medida no pré-operatório e até os dois primeiros meses também não mostraram diferenças estatísticas entre os grupos (p > 0,05). A avaliação da dor por meio da escala verbal mostrou vantagem no grupo que usou o plasma rico em plaquetas após 24 e 48 horas, uma e três semanas e dois meses de pós-operatório (p < 0,05).

Conclusões

Da maneira com que foi usado, o plasma rico em plaquetas não se mostrou efetivo para reduzir sangramento ou melhorar a função do joelho após a artroplastia em comparação com os controles. Houve vantagem na escala verbal de dor pós-operatória.

Palavras-chave: Artroplastia, Joelho, Transfusão, Plasma rico em plaquetas, Hemorragia

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty is deemed to be successful when complete tissue healing, pain control and good joint functioning are achieved.1

Major postoperative bleeding frequently occurs.1, 2 By minimizing the bleeding, the need for transfusion is avoided and formation of hematomas and seromas that might cause pain, impairment of the range of motion, disorders of wound healing and prolonged hospital stays are prevented.2, 3 Blood transfusion is subject to side effects, such as immunological reactions and infections.2, 3 Infections may occur directly through contamination4 or through greater susceptibility induced by means of immunomodulation.4 Use of autologous blood has not been shown to be a better option than the homologous blood that is routinely used.1, 5, 6 In an attempt to reduce the bleeding, many surgeons remove the tourniquet from the limb before closing the joint capsule and wound in order to achieve hemostasis. However, this not only increases the duration of the operation but also does not present proven efficacy.1, 7, 8, 9 Use of fibrin glue, which is produced from human plasma and, for this reason, is also subject to contamination and immunological reactions, has presented good results with regard to controlling bleeding, through acting as a hemostatic agent.10, 11, 12, 13

From the good initial results obtained with fibrin glue,10, 11, 12 but bearing in mind the risks of cross-contamination and the difficulty in obtaining this agent,11 Whitman et al. (1997)14 described the use of concentrates of autologous platelets for improving the healing. Antibacterial and antifungal effects have also been observed recently.15

Since then, products containing growth factors derived from platelets have been used under the name of platelet-rich plasma (PRP), in a variety of situations within medicine and dentistry.12 PRP is also known as platelet-enriched plasma (PeRP), platelet-rich concentrate (PRC) or autologous platelet gel.12 PRP has been produced by means of centrifugation of the patient's own blood, collected minutes before the surgery.2

The growth factors present in PRP are cytosines that come from blood and are part of the natural healing process. This process can be modified and accelerated according to the concentration of these factors.15 These cytosines have an important role in relation to cell proliferation, chemotaxis, cell differentiation and angiogenesis.15

In 2000, during the congress of the American Academy of Orthopedics, Mooar et al.16 demonstrated the use of autologous platelet gel during the postoperative period following implantation of total knee prostheses, for the first time, with good results.

Starting in 2006, studies on the use of PRP subsequent to total knee arthroplasty have been published, showing good results.1, 2, 3, 17 In these studies, use of PRP resulted in lower blood loss, fewer blood transfusions, better healing, less postoperative pain and infection and shorter hospital stay.1, 2, 3, 17 Two randomized prospective studies on this topic have been published so far. One of them did not show any benefit from PRP in relation to the controls,18 while the other study showed some benefit from using PRP, but without any statistical difference in the data relating to bleeding.17

The hypothesis of the present study was that use of PRP would be effective for controlling pain and bleeding and would improve the healing after total knee arthroplasty.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of PRP with regard to healing, pain and hemostasis after total knee arthroplasty.

Sample and methods

This was a blinded randomized clinical study. The project had been approved by our institution's research ethics committee.

Forty patients with an indication for total knee arthroplasty who were attended at our institution's outpatient clinic were selected.

The inclusion criteria were that the patient needed to have received explanations about the study and to present three-compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee. They could be of either sex and needed to have an indication for total knee prosthesis.

Patients presenting the following criteria were excluded: major deformities that would lead to more extensive bone cuts or soft-tissue release; inflammatory diseases; or previous surgery on the knee to be operated.

The patients were advised that, for inclusion in the study, they needed to sign the free and informed consent statement (Appendix 1).

Definition of the groups

The experimental group (20 patients) underwent implantation of a total knee prosthesis and received an intra-articular application of PRP.

The control group (20 patients) underwent implantation of a total knee prosthesis without receiving any intra-articular application of PRP.

The individuals were divided between the two groups randomly by means of a draw. The patients were not informed regarding the group to which they belonged and remained totally unaware of this information until the end of the project.

Data-gathering

Data-gathering (Table 1) before and after the operation comprised the following:

-

1.

Serum hemoglobin (Hb) and hematocrit (Ht) tests performed before the operation and 24 and 48 h after the operation. The need for transfusion was evaluated.

-

2.

Clinical examination of range of motion and pain. For this, goniometry and a verbal pain scale (scores between 0 and 10, such that 0 was free from pain and 10 was the worst pain) were used at the following times after the operation: 24–48 h, seven days, 21 days and two months. Any abnormalities of wound healing were also noted.

-

3.

To evaluate knee functioning before the operation and two months after the operation, the WOMAC instrument was used, in its version translated and validated for use in the Portuguese language19 (Appendix 2).

Table 1.

Model for the chart used to gather data on the parameters analyzed at the different assessment times, before and after the operation.

| Before | 24 h after | 48 h after | 7 days after | 21 days after | 2 months after | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb | X | X | X | |||

| Ht | X | X | X | |||

| ROM | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Pain | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| WOMAC | X | X | ||||

| Transfusion | X | X | ||||

| Wound | X | X | X | X | X |

Hb, hemoglobin; Ht, hematocrit; ROM, range of motion of the knee; Pain, verbal pain scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index19; Transfusion, evaluation of need for blood transfusion; Wound, observation of any abnormalities of healing.

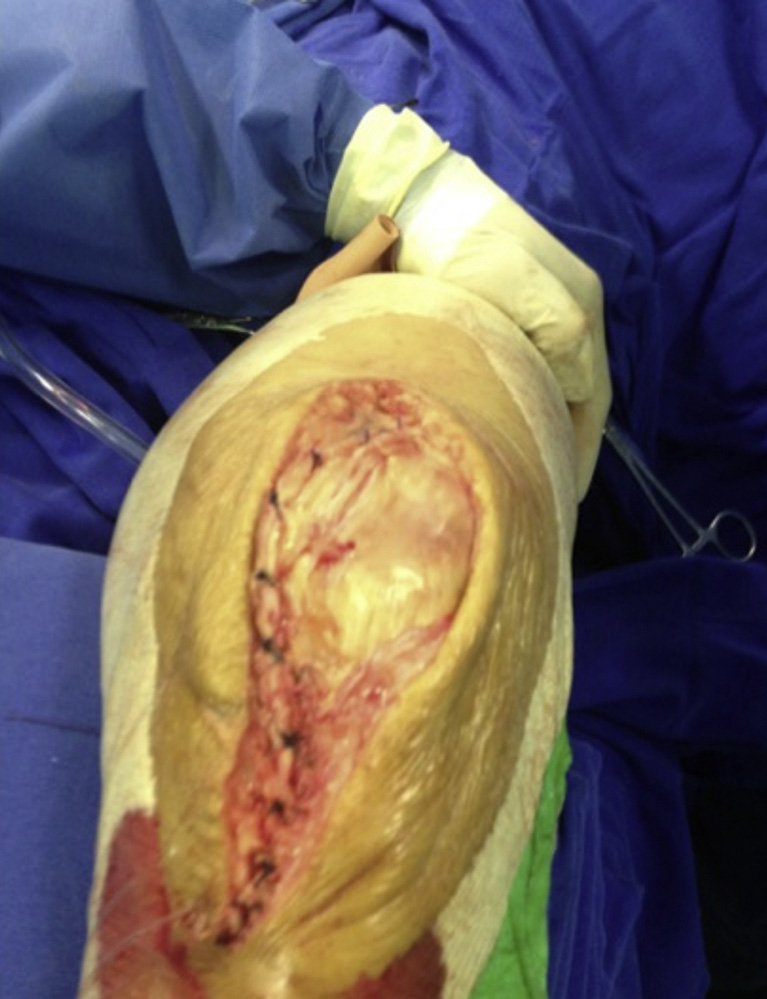

The surgical technique was the one established in the current literature, with medial patellar access and application of PRP to the entire exposed portion of the joint, in the cases selected for this (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6). All the procedures were performed by the same surgeon, using the same instruments and implanted material.

Fig. 1.

Joint exposed after cementation.

Fig. 2.

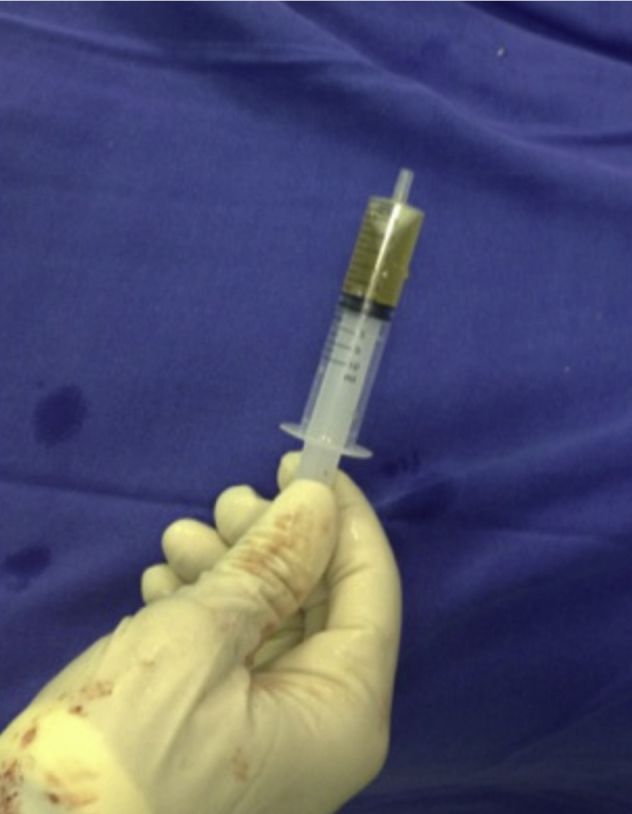

PRP immediately before application.

Fig. 3.

Application of PRP to the joint cavity.

Fig. 4.

Application of PRP to the joint cavity.

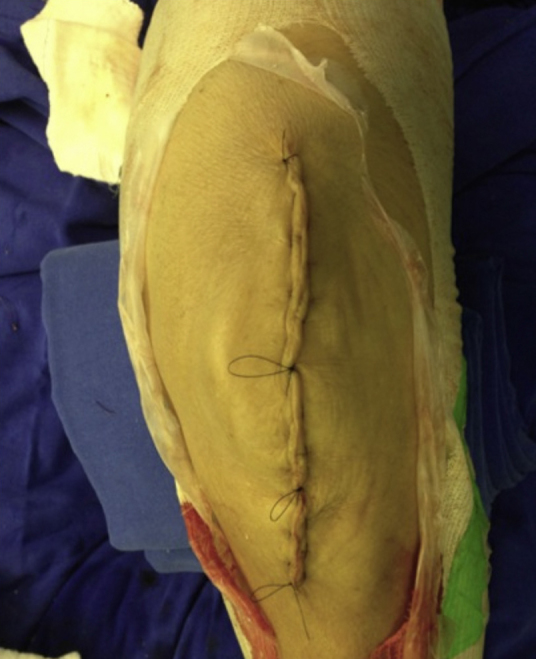

Fig. 5.

Closure of the joint capsule.

Fig. 6.

Closure of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

Postoperative protocol used

-

1.

During the hospital stay, the following was used as an analgesic: 1 g of dipyrone intravenously every six hours and 100 mg tramadol hydrochloride every eight hours;

-

2.

Patients with pain scored as more than seven on the verbal pain scale received 4 mg of morphine intravenously every four hours;

-

3.

After discharge from hospital, the patients were prescribed 1 g of dipyrone orally every six hours if pain occurred, and 50 mg of tramadol hydrochloride orally every six hours if the pain continued even after taking dipyrone;

-

4.

All the patients received prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis comprising a dose of 40 mg of enoxaparin subcutaneously, 24–48 h after the surgery, and they were prescribed 10 mg of rivaroxaban daily, for a further 10 days at home;

-

5.

Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered, comprising 2 g of cefazolin intravenously at the time when anesthesia was induced, followed by 1 g of cefazolin every eight hours for 48 h;

-

6.

The dressing was changed at the hospital on the second day after the operation, before discharge from the hospital, in the outpatient clinic on the seventh day and at home every day until the stitches were removed on the 21st day;

-

7.

The patients used a walking frame for 21 days, with full weight-bearing from the second postoperative day onwards;

-

8.

Physiotherapy was started while the patient was still in hospital and was continued until the second postoperative month after the operation;

-

9.

Radiological examinations were performed on the knees during the immediate postoperative period and in the outpatient clinic of Santa Casa at the outpatient visit two months after the operation;

-

10.

The parameters evaluated at the return visits were as follows: pain and symptoms relating to the knee; range of motion; satisfaction; and limb alignment and functioning (ability to walk, use of sticks, use of stairs and ramps, sitting down and standing up, etc.).

Preparation of the PRP

The PRP was prepared by a professional with skills and training for this process.

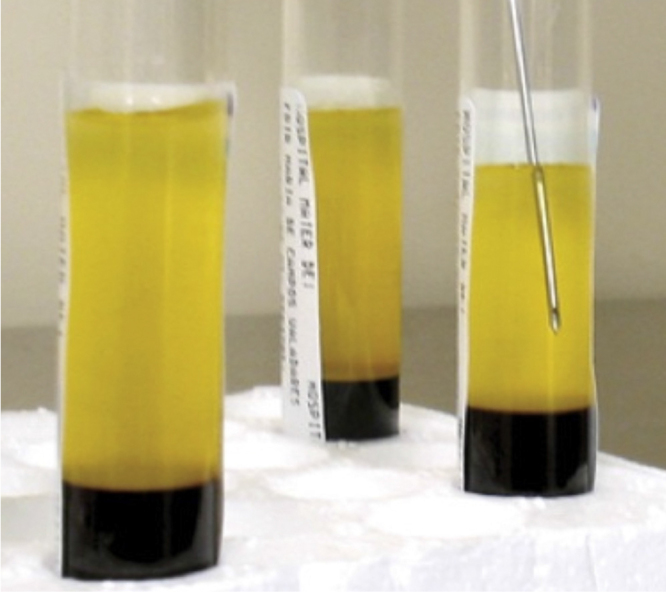

A sample of 20 mL of blood was collected from each patient in 5 mL vacuum tubes containing 10% sodium citrate for anticoagulation. The tubes were centrifuged (Fanem®) at 1200 rpm for 10 min, at room temperature in a centrifuge of radius 6.5 cm. The result from this centrifugation enabled separation of three components: red cells (bottom of the tube), white cells (thin layer on top of the red cells) and plasma (top layer) (Fig. 7). The plasma was decanted into another sterile tube, of capacity 10 mL, and was centrifuged again in the same machine at the same speed, for five minutes. At the end of this centrifugation, the upper plasma layer that was obtained (accounting for approximately 50%) was discarded because of the small quantity of platelets. The lower portion, which was rich in platelets and was named platelet-rich plasma, was placed in a sterile Petri dish in the surgical field. Following this, it was placed in a syringe for the surgeon to apply. A proportion of the PRP from every fifth patient was separated out and subjected to analysis on the number of platelets, in an automatic counter (ADVIA 120 Siemens®).

Fig. 7.

Plasma being removed.

Statistical analysis

For the variables Hb and Ht, the technique of analysis of variance was used, in a model of repeated measurements in independent groups, complemented by the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.20

In the evaluations on the range of motion, verbal pain scale and functioning, the nonparametric model analysis of variance model of repeated measurements in independent groups was used, complemented by the Dunn multiple comparisons test.21

Results

The patients’ mean age was 67.7 years (range: 50–86). In the PRP group, this mean was 66.4 years (range: 50–86) and in the control group, 71.6 years (range: 55–81). The mean duration of the operation was 91.4 min (range: 70–105): 90.7 (80–105) in the PRP group and 91.5 (70–95) in the control group. The distribution showed that there were 14 male patients: six in the PRP group and eight in the control group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean and minimum and maximum values for age, sex distribution and duration of surgery among the patients.

| PRP group | Control group | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 20 | 20 | 40 |

| Age (years) | 66.4 (50–86) | 71.6 (55–81) | 67.7 |

| Sex (M/F) | 6/14 | 8/12 | 14/26 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 90.7 (80–105) | 84.3 (70–95) | 86.8 (70–105) |

| Transfusion | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In the platelet counts, it was found that in the cases of poorest yield of platelets, the number was twice the initial quantity present in the plasma of that patient. There were some patients for whom the platelet count after the second centrifugation was four times as great (Table 3).

Table 3.

Platelet counts before the operation and in the PRP preparation.

| Platelet counts | Serum platelet assay | Platelet assay on PRP |

|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 PRP group | 316,000 | 950,000 |

| Patient 6 PRP group | 411,000 | 1,138,000 |

| Patient 11 PRP group | 223,000 | 777,000 |

| Patient 16 PRP group | 416,000 | 1,088,000 |

None of the patients in this study needed to have transfusions. The criterion for transfusion used here was a hemoglobin concentration of less than 7 mg/dL in symptomatic patients during the postoperative period. There were three patients who presented dehiscence of the operative wound and superficial infection. These patients were treated using dressings and oral antibiotics, and full healing was achieved in these cases. Two of them were in the PRP group. There were no cases of thromboembolism.

Table 4 shows that there were no statistically significant differences between the groups with regard to the pre and postoperative values for the variables of hemoglobin, hematocrit, range of motion or WOMAC questionnaire score.19 In the pain assessment, there was a significant advantage in the group that used PRP.

Table 4.

Comparison between the PRP and control groups.

| PRP | Control | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | |||

| Before operation | 11.610 (1.405) | 12.105 (1.611) | >0.05 |

| 24 h after operation | 10.285 (1.467) | 10.759 (1.686) | >0.05 |

| 48 h after operation | 9.605 (1.259) | 9.841 (1.454) | >0.05 |

| Hematocrit (%) | |||

| Before operation | 35.030 (3.508) | 36.618 (4.803) | >0.05 |

| 24 h after operation | 30.930 (3.525) | 32.227 (5.199) | >0.05 |

| 48 h after operation | 29.225 (3.443) | 29.545 (4.381) | >0.05 |

| ROM (degrees) | |||

| Before operation | 115 (45; 130) | 115 (55; 120) | >0.05 |

| 24 h after operation | 55 (30; 85) | 55 (30; 85) | >0.05 |

| 48 h after operation | 75 (60; 85) | 75 (55; 85) | >0.05 |

| 7 d after operation | 82.5 (60; 100) | 82.5 (60; 100) | >0.05 |

| 21 d after operation | 95 (60; 110) | 90 (45; 105) | >0.05 |

| 2 m after operation | 97.5 (45; 120) | 95 (45; 120) | >0.05 |

| Pain (scores from 0 to 10) | |||

| 24 h after operation | 6.0 (2.0; 8.0) | 7.0 (4.0; 8.0) | <0.05 |

| 48 h after operation | 3.0 (0.0; 6.0) | 4.0 (2.0; 6.0) | <0.05 |

| 7 d after operation | 2.0 (0.0; 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0; 3.0) | <0.05 |

| 21 d after operation | 1.0 (0.0; 2.0) | 2.0 (0.0; 3.0) | <0.05 |

| 2 m after operation | 0.0 (0.0; 2.0) | 1.0 (0.0; 3.0) | <0.05 |

| WOMAC (between 0 and 96) | |||

| Before operation | 45.5 (30.0; 54.0) | 46.0 (21.0; 60.0) | >0.05 |

| 2 m after operation | 70.0 (59.0; 80.0) | 72.0 (0.0; 82.0) | >0.05 |

ROM, range of motion of the knee; Pain, verbal pain scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index.19

Discussion

Variations in the ways of obtaining, preparing and applying PRP currently constitute a limitation on any comparison between studies.22 A recent systematic review on PRP use in chondral lesions consulted 254 citations and, after applying rigorous exclusion criteria, selected 21 for study. Even so, 10% of these did not report the method used for obtaining the PRP and 28.6% did not report the platelet concentration of the preparation.23

In another study that evaluates this common variation between PRP preparations, blood samples were collected from each of the eight patients and these were subjected to three different centrifugation methods. All of these methods considerably increased the number of platelets in the concentrate, but it was seen that there was variation in the growth factor concentrations between individuals and between different samples from the same individual.24

The PRP preparation in this study followed techniques that had previously been described.25, 26 The platelet counting proved that high concentrations were produced (between two and four times the level in the plasma). In addition to the platelet concentrations, the types of PRP can be differentiated according to the concentration of leukocytes and their form of activation.22 In the present study, the leukocytes were separated from the PRP that was obtained, and we chose endogenous platelet activation, i.e. done by means of the collagen and other activation factors of the joint cavity that was exposed.27 All the previous studies on application of PRP in cases of knee arthroplasty presented (when documented) platelet concentrations similar to those used in the present study with leukocyte separation.1, 2, 3, 17, 18, 28 In these studies, the PRP was activated using calcified thrombin, prior to application. Endogenous activation by means of collagen shows a cytokine release pattern of longer duration, of a more sustained nature than that of exogenous activation27 and for this reason, it was done in the present study. In the natural healing process, the collagen exposed in the wounded tissue is frequently the initial activator and generates platelet adhesion in a single layer over itself. Subsequently, there is superposition of platelets by means of the thrombin route. This manner, which is closer to the natural method of delayed activation, is functionally useful for ensuring that growth factor release does not occur prematurely, i.e. before complete formation of a provisional scaffold.27

In 2009, in the first randomized controlled study on the use of PRP in cases of knee arthroplasty that was published, no benefits were shown.18 The PRP used was activated before its application in the form of a spray, and the bleeding was quantified through the difference in hemoglobin values from before the operation to 24 h after the operation. As reported earlier, endogenous activation may have led to better results and, as confirmed in the present study, there was also a notable decline in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels between 24 and 48 h after the operation.

In another randomized study in which PRP was used in cases of total knee arthroplasty with the aim of reducing the bleeding, its use did not make a significant difference, even though there was a positive difference in relation to the postoperative bleeding.17 One of the possible reasons for this, according to the authors of that study, was that their use of drainage after the operation might have led to loss of PRP.17 For this reason, we chose not to use drainage in the present study. Nonetheless, we did not find any statistically significant results in relation to bleeding. Another reason that was pointed out as a possible cause of lack of statistical significance in the results from that study was the small number of patients, which may have been the same limitation as in the present study. This study also showed that the pain level was lower in the group that used PRP in the postoperative evaluation.17

In our study, the analysis on pain, as shown by the verbal pain scale, also showed that the group that used PRP had an advantage. This advantage, which was not shown in the other variables analyzed, led to lower use of morphine in this group during the hospital stay (only one patient used it, versus three in the control group). Two months after the operation, another analysis on pain using the verbal scale still showed that the pain level in the PRP group was better, although this was proven in the pain and function questionnaire (WOMAC). It had already been documented in a previous uncontrolled study that PRP had a positive effect with regard to improvement of postoperative pain.3 PRP has a proven anti-inflammatory effect and has been used with this function in relation to other pathological conditions.29 This, therefore, may explain the results found in the present study.

Despite the pain control proven in this and other studies, another recently published retrospective study on the use of PRP in relation to knee prostheses, with more than 200 patients and without the use of postoperative drains also did not show any improvement in bleeding.28 In the present study, the bleeding was measured through the decline in hemoglobin levels, only 24 h after the operation.

In two patients in the PRP group and in only one in the control group, there was dehiscence of the suture and superficial infection. Thus, we did not find any evidence in relation to any antibacterial effect15 or any advantage in relation to healing of the operative wound. A previous study demonstrated bacterial growth in PRP.30 Preparation of this, outside of the laminar flow hood, as done in the present study, may facilitate contamination.

The limitations of the present study include the small number of patients, which may have interfered with the result from the statistical analysis. Another factor relates to the study design, which allowed the surgeon to be aware of the group to which the patient belonged, at the time of performing the operation. The lack of quantification of the growth factors and the number of residual leukocytes in the PRP samples is also a factor that may have limited the discussion of the results obtained.

Conclusion

In the manner in which PRP was used, it was not shown to be effective for reducing the bleeding or improving the functioning of the knee after arthroplasty, in comparison with the controls. There was an advantage on the verbal scale for postoperative pain.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude toward the biochemist Maria Madalena Sbizera and the statisticians Renam Mercuri Pinto and Carlos Roberto Padovani.

Footnotes

Work developed at Santa Casa de Londrina, PR, Brazil and at the Hemocenter of Botucatu Medical School (UNESP), Botucatu, SP, Brazil.

Appendix 1. Free and informed consent statement.

| This study has the title “Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) applied during total knee arthroplasty”. Dr. João Paulo Fernandes Guerreiro, a doctor within the clinical staff of Irmandade da Santa Casa de Londrina, will conduct a clinical study within this institution that involves total knee arthroplasty on 40 patients, using a currently well-established surgical technique. In 20 patients, we will apply platelet-rich plasma (PRP) before closing the wound. PRP is a substance made from a sample of the patient's own blood, collected at the time of starting the anesthesia. The objective of the study is to analyze the benefits that PRP might bring toward controlling pain and bleeding and improving healing. PRP is a part of human blood that contains a large quantity of platelets. Platelets are cells that participate in blood coagulation when blood comes into contact with wounds. The PRP used in this study will be removed from the same patient during anesthesia. Regarding the risks of the surgery, these include edema (swelling), bleeding (with possible blood transfusion during or after the operation) and/or hematoma; dehiscence of the surgical wound (breakage of stitches or opening or the surgical wound); postoperative pain; joint stiffness (movement limitation); anesthetic accidents; complex regional pain syndrome; venous thrombosis and its consequences (formation of a coagulum that causes obstruction of the veins); temporary or definitive functional incapacity (in relation to activities of daily living, work activities, sports or other activities); superficial infection; deep infection and its consequences (difficult to treat and eradicate, with the need for new hospitalizations and surgical interventions for cleaning and removal of fixation materials, and probable sequelae such as functional limitation or loss of the limb operated); neurovascular injuries (injuries to nerves that may compromise the sensitivity and movement of a given region of the body and/or limb; arterial lesions that may compromise the blood irrigation of a given region and/or limb). The mean time taken to perform the surgery is 100 minutes. Evaluations will be made by means of physical examinations during the hospital stay (generally for two days after the surgery) and then at the following times after the surgery: 7, 10 and 21 days; 2, 6 and 12 months; and annually thereafter. Radiographs of the knee will be performed 2, 6 and 12 months after the surgery and annually thereafter, in the same way as is done routinely among our patients. During the postoperative period, it is common to have some degree of pain, but this improves with the medication that will be prescribed. There may be some swelling of the knee, which can be treated with medication sand ice compresses. Slight bleeding may also occur on the first days. Any other doubt should be clarified with the doctor. 1.1. Therefore, we request your consent to include you in our study and we assure you than confidentiality will be maintained. We will make use of your participation for the scientific evaluation and possible publication of this study, within the ethical principles that must guide research and our profession. We would also like to make it clear that your participation will not imply any financial remuneration. If your do not wish to participate, you are free to opt out, both at the outset or during the course of the work, without any personal losses. If you have any queries, you can contact the researcher directly through this telephone number: (43) 3377 0900. In an emergency, you can seek assistance at the orthopedic emergency service of Santa Casa de Londrina, telephone: (43) 3373 1671. You may also contact the bioethics and research ethics committee of Irmandade da Santa Casa de Londrina, telephone: (43) 3373 1643. We thank you for your valuable contribution. _______________________________ Researcher's signature I declare that I have been informed about the study and I agree to participate. DATE: ________________ Name____________________________________________________________ _____________________________ Signature |

Appendix 2. Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index (WOMAC)

| Category 1 – Severity of the pain (during the last month) in relation to: |

| Walking: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Going up stairs: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Pain at night: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Pain when resting ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| When carrying weights: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Morning stiffness: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Protokinetic stiffness: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Category 2 – Level of difficulty in carrying out the following functions: |

| Going down stairs: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Going up stairs: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Getting up from a chair: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Standing up: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Bending to the ground: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Walking on a level surface: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Getting into or out of a car: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Shopping: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Putting socks on: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Getting out of bed: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Taking socks off: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Lying down on a bed: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Getting into and out of a bath: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Sitting down: ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Sitting down on and getting up from the toilet: |

| ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Carrying out light domestic tasks: |

| ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Carrying out heavy domestic tasks: |

| ( ) none ( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe |

| Counting the points and calculating the score: |

| Response “none” – 4 points; “mild” – 3; “moderate” – 2; and “severe” – 0. |

| Total number of points: |

References

- 1.Gardner M.J., Demetrakopoulos D., Klepchick P.R., Mooar P.A. The efficacy of autologous platelet gel in pain control and blood loss in total knee arthroplasty. An analysis of the haemoglobin, narcotic requirement and range of motion. Int Orthop. 2007;31(3):309–313. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0174-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everts P.A., Devilee R.J., Brown Mahoney C., Eeftinck-Schattenkerk M., Box H.A., Knape J.T. Platelet gel and fibrin sealant reduce allogeneic blood transfusions in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50(5):593–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.001005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berghoff W.J., Pietrzak W.S., Rhodes R.D. Platelet-rich plasma application during closure following total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2006;29(7):590–598. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20060701-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosco J.A., 3rd, Slover J.D., Haas J.P. Perioperative strategies for decreasing infection: a comprehensive evidence-based approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(1):232–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birkmeyer J.D., Goodnough L.T., AuBuchon J.P., Noordsij P.G., Littenberg B. The cost-effectiveness of preoperative autologous blood donation for total hip and knee replacement. Transfusion. 1993;33(7):544–551. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1993.33793325048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etchason J., Petz L., Keeler E., Calhoun L., Kleinman S., Snider C. The cost effectiveness of preoperative autologous blood donations. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(11):719–724. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503163321106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hersekli M.A., Akpinar S., Ozkoc G., Ozalay M., Uysal M., Cesur N. The timing of tourniquet release and its influence on blood loss after total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2004;28(3):138–141. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0550-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorn L.P., Lindstrand A., Toksvig-Larsen S. Tourniquet release for hemostasis increases bleeding. A randomized study of 77 knee replacements. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(3):265–267. doi: 10.3109/17453679908997804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christodoulou A.G., Ploumis A.L., Terzidis I.P., Chantzidis P., Metsovitis S.R., Nikiforos D.G. The role of timing of tourniquet release and cementing on perioperative blood loss in total knee replacement. Knee. 2004;11(4):313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matras H. Effect of various fibrin preparations on reimplantations in the rat skin. Osterr Z Stomatol. 1970;67(9):338–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibble J.W., Ness P.M. Fibrin glue: the perfect operative sealant? Transfusion. 1990;30(8):741–747. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1990.30891020337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohan Ehrenfest D.M., Rasmusson L., Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27(3):158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy O., Martinowitz U., Oran A., Tauber C., Horoszowski H. The use of fibrin tissue adhesive to reduce blood loss and the need for blood transfusion after total knee arthroplasty. A prospective, randomized, multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(11):1580–1588. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199911000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitman D.H., Berry R.L., Green D.M. Platelet gel: an autologous alternative to fibrin glue with applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55(11):1294–1299. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sánchez M., Anitua E., Orive G., Mujika I., Andia I. Platelet-rich therapies in the treatment of orthopaedic sport injuries. Sports Med. 2009;39(5):345–354. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mooar P.A., Gardner M.J., Klepchick P.R., Mooar P.A. 67th Annual Meeting. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2000. The efficacy of autologous platelet gel in total knee arthroplasty: an analysis of range of motion, hemoblobin, and narcotic requirements; p. PE148. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horstmann W.G., Slappendel R., van Hellemondt G.G., Wymenga A.W., Jack N., Everts P.A. Autologous platelet gel in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(1):115–121. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peerbooms J.C., de Wolf G.S., Colaris J.W., Bruijn D.J., Verhaar J.A. No positive effect of autologous platelet gel after total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(5):557–562. doi: 10.3109/17453670903350081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes M.I. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola Paulista de Medicina; São Paulo: 2003. Tradução e validação do questionário de qualidade de vida específico para osteoartrose Womac (Western Ontario McMaster Universities) para a língua portuguesa. [dissertação] Available from: http://www.biblioteca.epm.br/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson R.A., Wichern D.W. 6th ed. Prentice-Hall; New Jersey: 2007. Applied multivariate statistical analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zar J.A. 5th ed. Prentice-Hall; New Jersey: 2009. Biostatistical analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeLong J.M., Russell R.P., Mazzocca A.D. Platelet-rich plasma: the PAW classification system. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):998–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.04.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smyth N.A., Murawski C.D., Fortier L.A., Cole B.J., Kennedy J.G. Platelet-rich plasma in the pathologic processes of cartilage: review of basic science evidence. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(8):1399–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzocca A.D., McCarthy M.B., Chowaniec D.M., Cote M.P., Romeo A.A., Bradley J.P. Platelet-rich plasma differs according to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):308–316. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marx R.E. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(4):489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weibrich G., Kleis W.K. Curasan PRP kit vs. PCCS PRP system. Collection efficiency and platelet counts of two different methods for the preparation of platelet-rich plasma. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13(4):437–443. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison S., Vavken P., Kevy S., Jacobson M., Zurakowski D., Murray M.M. Platelet activation by collagen provides sustained release of anabolic cytokines. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(4):729–734. doi: 10.1177/0363546511401576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diiorio T.M., Burkholder J.D., Good R.P., Parvizi J., Sharkey P.F. Platelet-rich plasma does not reduce blood loss or pain or improve range of motion after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):138–143. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1972-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khoshbin A., Leroux T., Wasserstein D., Marks P., Theodoropoulos J., Ogilvie-Harris D. The efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review with quantitative synthesis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(12):2037–2048. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee H.R., Seo J.W., Kim M.J., Song S.H., Park K.U., Song J. Rapid detection of bacterial contamination of platelet-rich plasma-derived platelet concentrates using flow cytometry. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2012;42(2):174–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]