Abstract

The implications of global population growth urge transformation of current food and bioenergy production systems to sustainability. Members of the family Poaceae are of particular importance both in food security and for their applications as biofuel substrates. For centuries, rust fungi have threatened the production of valuable crops such as wheat, barley, oat, and other small grains; similarly, biofuel crops can also be susceptible to these pathogens. Emerging rust pathogenic races with increased virulence and recurrent rust epidemics around the world point out the vulnerability of monocultures. Basic research in plant immunity, especially in model plants, can make contributions to understanding plant resistance mechanisms and improve disease management strategies. The development of the grass Brachypodium distachyon as a genetically tractable model for monocots, especially temperate cereals and grasses, offers the possibility to overcome the experimental challenges presented by the genetic and genomic complexities of economically valuable crop plants. The numerous resources and tools available in Brachypodium have opened new doors to investigate the underlying molecular and genetic bases of plant–microbe interactions in grasses and evidence demonstrating the applicability and advantages of working with B. distachyon is increasing. Importantly, several interactions between B. distachyon and devastating plant pathogens, such rust fungi, have been examined in the context of non-host resistance. Here, we discuss the use of B. distachyon in these various pathosystems. Exploiting B. distachyon to understand the mechanisms underpinning disease resistance to non-adapted rust fungi may provide effective and durable approaches to fend off these pathogens. The close phylogenetic relationship among Brachypodium spp. and grasses with industrial and agronomic value support harnessing this model plant to improve cropping systems and encourage its use in translational research.

Keywords: Brachypodium, rust fungi, Puccinia, plant immunity, non-host resistance

Introduction

Cereals, which are classified within the grass family Poaceae, also known as Gramineae, are essential worldwide commodities (Chapman, 1996). The importance of these plant species ranges from economic to ecological, and stems from their multiple applications in industry, food production, livestock feed, generation of renewable and sustainable energy among others. The critical role of cereals in human nutrition is highlighted by the fact that wheat, corn, and rice provide nearly two thirds of the global caloric intake (Tilman et al., 2011). Other crops, like oat and millet, exemplify the extraordinary nutritional value that cereals can provide (Bewley et al., 2012; Shukla and Srivastava, 2014). In a different context, the cultivation of grasses such as switchgrass, sweet sorghum, Miscanthus, and especially sugarcane and corn, are the main basis of biofuel production (Somerville, 2007) increasing the value of these plant species.

According to predictions of worldwide population growth, agricultural production must increase approximately twofold to meet the dietary needs of nine billion people in the year 2050 (US Census Bureau, 2015; Tilman et al., 2011). In addition to this, crop production systems need to consider a dietary bias toward higher consumption of meat and dairy, and the demands of increasing biomass to support biofuel production (Ray et al., 2013). Increasing crop yields and boosting agricultural production are among the greatest challenges humanity faces, as research suggests current crop yield trends are not on track to reach our target food production (Ray et al., 2013). Unpredictable and recurrent epidemics caused by plant pathogens are factors that have hampered productivity of crops since the birth of agriculture about 10,000 years ago (Oerke, 2006). The mid 1800s Irish potato famine caused by the oomycete Phytophthora infestans (Woodham-Smith, 1991) and other similar epidemics demonstrate the influence of plant diseases in history and society (Schumann, 1991). Currently, pre-harvest plant disease causes an approximately 15% loss of global crop production (Popp and Hantos, 2011).

The global production of small grains is severely affected by rust fungi (Maier et al., 2003). Some of these economically important pathogens include members of the genus Puccinia such as P. graminis, which affects production of wheat (Triticum aestivum and T. durum), barley (Hordeum vulgare) and oat (Avena sativa), P. triticina, the causal agent of wheat leaf rust, P. striiformis, which causes stripe rust on wheat, and P. coronata, the causal agent of oat crown rust (Cummins, 1971). In fact, the recurrent outbreaks of P. coronata f. sp. avenae and the rapid emergence of hypervirulent races of the wheat stem rust fungus, P. graminis f. sp. tritici (i.e., TTKSK) are two examples that illustrate the potential devastating economic effects of rust fungi on crops around the globe (Pretorius et al., 2000; Leonard and Martinelli, 2005; Singh et al., 2006; Park, 2008; Pennisi, 2010). This review discusses the biological attributes of rust fungi, and how those characteristics can contribute to expand our knowledge in plant immunity. We focus on the development of Brachypodium-rust pathosystems, which are important at two fronts, first helping us to understand the principles of non-host resistance (NHR) and second holding promise to enhance disease resistance engineering technologies.

The Two Faces of Rust Fungi—Dangerous Pathogens and Good Models

Rust fungi exhibit complex lifecycles with both sexual and asexual (clonal) cycles of reproduction. In the case of the previously listed Puccinia species, sexual reproduction is completed on an alternate host as these pathogens undergo a heteroecious life cycle (Al-Kherb et al., 1987; Jin et al., 2010). In contrast, other rust fungi known to be autoecious, like the causal agent of flax rust Melampsora lini, depend solely on one host to complete both asexual and sexual reproduction (Lawrence et al., 2007). An interesting biological characteristic of rust fungi is that they generally show high levels of host specificity, although there is variability in host range exhibited by these pathogens. For instance, species like P. triticina infect a limited number of plant species (Roelfs et al., 1992), while others like P. graminis and P. coronata have a host range in the order of hundreds of related species (Anikster, 1984; Wahl et al., 1984; Leonard and Szabo, 2005). However, in these cases, the rust species can generally be classified into different physiological variants known as formae speciales (ff. spp.), each of them having a much more restricted host range (Anikster, 1984). For example, P. graminis f. sp. avenae affects only oat production, while P. graminis f. sp. tritici targets barley and wheat (Leonard and Szabo, 2005). The investigation of the evolutionary and physiological factors determining host range and specificity of rust species and formae speciales is of interest as those factors could provide insights into the mechanisms that drive pathogen jumps from one host species to another and the emergence of new diseases (Bettgenhaeuser et al., 2014). Unraveling the riddles of sexual reproduction in rust fungi, the biological contribution of alternate hosts in introducing genetic variation, particularly virulence alterations, can also help understand the rise of new pathogens or pathotypes.

Rust fungi have co-evolved with their respective host(s) for millions of years, a process that has resulted in the adoption of complex and effective infection strategies involving specialized cell types and morphological structures (Harder, 1984; Harder and Chong, 1984; Wahl et al., 1984). Such complexity is manifested by the production of up to five type of spores: basidiospores, pycniospores, aeciospores, urediniospores, and teliospores. However, most research in developmental biology of rust fungi has been directed to the infection mediated by urediniospores as they are responsible for multiple infection cycles in the gramineous host with agronomic value (Leonard and Szabo, 2005). P. graminis f. sp. tritici is one of the best characterized pathogenic rust fungi and has been widely used to describe the morphological differentiation processes associated with rust diseases of cereals. The elaborate developmental program followed by rust fungi is initiated by the recognition of the host environment, where chemical, thigmotropic and topographical characteristics of the leaf surface prompt hyphal growth and orientation (Hoch et al., 1987; Heath, 1997; Brand and Gow, 2012). Moisture on the leaf surface induces the germination of urediniospores, a process that is followed by the elongation of a germ tube and location of a stoma, which serves as a cue to form an appressorium and gain access to internal cavities of the plant (Staples and Macko, 2004; Leonard and Szabo, 2005). The course of infection continues with the differentiation of a substomatal vesicle and the emergence of a primary hypha that quickly extends in the plant mesophyll space. During more advanced stages of infection, feeding structures, referred to as haustoria, penetrate the walls of living plant cells, and invaginate the host plasma membrane forming an intimate association with the plant (Harder and Chong, 1984; Staples and Macko, 2004). Finally, the colonization leads to sporulation and the generation of uredial pustules erupting through the epidermis of the leaf (Leonard and Szabo, 2005). Management of diseases caused by rust fungi is often a difficult task as the pathogen grows asymptomatically during colonization and disease does not manifest until the fungus is undergoing sporulation (Leonard and Szabo, 2005). In this context, furthering our understanding of biochemical and molecular events particularly during early stages of infection should be regarded as a research priority.

The effectiveness of introducing disease resistance into crops to counteract the negative effect of rust fungi was established in the very early days of plant breeding with the identification of a resistance gene effective against P. striiformis (Biffen, 1907). Early studies in the flax-M. lini pathosystem played an important role in establishing the concepts of plant immunity, especially Flor’s research leading to the “gene-for-gene” model, and demonstrate the usefulness of rust fungi to uncover the most fundamental principles in plant pathology (Flor, 1971; Lawrence et al., 2007; Ellis et al., 2014). It is now evident that the genetically determined plant immune system constitutes the underlying basis of breeding crop plants for pathogen resistance and dissecting the factors that govern the onset of rust disease can bring innovation to crop protection programs (Dodds and Rathjen, 2010). The distinctive morphological features that rust fungi adopt during infection, as well as the extended period of time that these pathogens spend in contact with their host, enable ideal experimental systems to elucidate how the fungus copes with the plant defenses and resolve molecular changes in relationship to infection stages at a high-resolution.

The Plant Immune System and the Pursuit of Crop Health

In nature plants are constantly threatened by different microorganisms; however, the development of disease as an outcome of those interactions is rather uncommon (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Lipka et al., 2010). Whether a plant is suitable as a host to a particular would-be pathogen is partly conferred by a battery of physiological and biochemical immune responses that result in a wide array of phenotypes ranging from complete immunity (incompatibility) to full susceptibility (compatibility). Plant disease resistance has been classified historically as either host resistance, describing resistance that is specific to a plant cultivar, variety or accession to a pathogen that is able to infect other host genotypes of that species (Flor, 1971; Jones and Dangl, 2006; Dodds and Rathjen, 2010), or NHR, referring to a type of resistance that is present across all genotypes of a plant species and prevents infection by any genetic variants (i.e., formae speciales, races, isolates) of a given non-adapted pathogen (Heath, 1981, 2000; Mysore and Ryu, 2004; Bettgenhaeuser et al., 2014). Considering that most of the naturally occurring disease resistance is attributed to NHR, this type of plant immunity holds great promise to agricultural practices as means to provide durable and broad-spectrum resistance (Mysore and Ryu, 2004; Ellis, 2006; Schulze-Lefert and Panstruga, 2011). Our present understanding of the mechanisms underlying NHR is much less extensive than the accumulated body of knowledge that conveys the molecular basis of host resistance. Recent evidence suggests that components mediating host resistance are likely important determinant factors in NHR, and thus both types of resistance may share some of the same inducible responses (Huitema et al., 2003; Mysore and Ryu, 2004; Douchkov et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014). Consequently, the distinction between host and NHR may not truly reflect mechanistic differences among the two types of resistance, as both phenomena may exploit the same means of pathogen perception and defense.

Microbial recognition follows a two-tier system, enabling the plant to mount a defense response that may or may not be effective depending on the physiological characteristics of the would-be pathogen. First, the plant is equipped to recognize conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as the fungal cell wall component chitin (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Dodds and Rathjen, 2010). This phenomenon, known as PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI), is thought to be particularly relevant in NHR as it effectively prevents infection by non-adapted pathogens (Schulze-Lefert and Panstruga, 2011). PTI operates via plant cell surface-associated receptors (pattern recognition receptors, PRRs) that activate various basal defense responses such as callose deposition, production of reactive oxygen species, activation of pathogenesis-related proteins, etc. (Monaghan and Zipfel, 2012; Fu and Dong, 2013). The second tier of plant defense, known as effector-triggered immunity (ETI), exploits the backbone of many pathogens’ virulence strategies. Pathogens secrete proteins and small molecules, known as effectors, which among other functions can suppress or inhibit PTI-associated defense responses to allow infection to proceed (Hogenhout et al., 2009; Koeck et al., 2011). During ETI, the plants recognize effectors via intracellular receptor proteins of the nucleotide binding leucine rich repeat (NB-LRR) class, turning on complex cellular responses in order to restrict pathogen growth. These receptors are encoded by resistance (R) genes, and, in general, embody the traditional “gene-for-gene” concept initially described in the flax rust pathosystem (Flor, 1971; Jones and Dangl, 2006; Dodds and Rathjen, 2010). The recognition of effectors is typically associated with a rapid and localized cell death reaction at the site of infection, known as the hypersensitive response (HR); however, HR-like cell death can also occur during PTI (Khatib et al., 2004). The ETI concept is generally considered to encompass recognition of effectors delivered/translocated into the host cell; however, some effectors accumulate in apoplastic space and exert their function extracellularly (Hogenhout et al., 2009). Some of these apoplastic effectors are recognized by plasma membrane-associated receptors in the plant via a mechanism that differs from ETI and PTI (Stotz et al., 2014). This type of resistance, named effector-triggered defense (ETD), is commonly associated with apoplastic fungal leaf pathogens and can be manifested as slow developing cell death (Stotz et al., 2014). Regardless of the terminology and mechanistic differences between ETD and ETI, ETD should be regarded as part of the second tier of microbial recognition as its fundamental principle is still recognition of effector molecules. Successful infection by rust fungi requires haustorium-mediated delivery and translocation of effectors into the invaded plant cells (Catanzariti et al., 2006, 2007; Panstruga and Dodds, 2009; Garnica et al., 2014), and while the secretion of effectors via other structures has not been demonstrated it is possible that those events take place and are relevant to the rust pathogen–plant interaction outcomes. The presence of apoplastic effectors produced by rust fungi has not been demonstrated either, but it seems reasonable to think that this class of effectors could be important during early stages of rust infection, prior the differentiation of the first haustorium. Barley-P. graminis interactions mediated by the Rpg1 gene clearly begin before haustorial formation since the RPG1 protein is phosphorylated within 5 min of spores from avirulent pathotypes contacting the leaf surface (Nirmala et al., 2010). According to these findings, two effector proteins required for the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of RPG1 are present on the spore surface and probably other fungal structures (Nirmala et al., 2011).

In addition to immune system-induced resistance, genetic protection from disease can occur through the action of resistance genes that have other effects. These genes often provide broad-spectrum resistance against multiple pathogens, and, although frequently referred to as resistance genes, do not necessarily encode receptor-like proteins like NB-LRR proteins. An example of this type of resistance in wheat is the response conditioned by the gene Lr34, which encodes a putative adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette (ABC) transporter protein, and confers partial resistance against leaf, stem and stripe rust fungi, as well as barley yellow dwarf virus and powdery mildew (Dyck et al., 1966; Singh, 1993; Krattinger et al., 2009; Risk et al., 2013). In summary, this broad array of defense mechanisms represents targets that may be exploited in various strategies to prevent and minimize crop losses.

Brachypodium distachyon: A Model System that Defies Rust Diseases

Throughout research history, the use of experimental model organisms such as Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Neurospora crassa, and Caenorhabditis elegans have accelerated scientific discovery and led to significant breakthroughs (Miklos and Rubin, 1996; Guarente and Kenyon, 2000; Davis and Perkins, 2002; Replansky et al., 2008). Research in wheat, oat, and other monocots often faces long-standing challenges associated with the ploidy of the plants and the large size of their genomes (Chawade et al., 2010; Mayer et al., 2014). The use of representative model species can help circumvent those problems and accelerate the pace of research. In addition, leveraging basic knowledge from model organisms for applied purposes, such as disease resistance, can be extremely advantageous to crop improvement. Dicotyledonous species such as Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress or mouse-ear cress) and Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) have served as excellent models to elucidate the plant immune system, understand the basis of plant–microbe interactions and have made significant contributions to crop improvement (Piquerez et al., 2014). However, dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants diverged at least 140–150 million years ago (Chaw et al., 2004; Davies et al., 2004; Anderson et al., 2005) and the substantial phylogenetic distance between cereals and dicots can often hinder downstream applications of knowledge gained from dicot models to cereal research and breeding. Thus, there is need for developing appropriate systems to study monocotyledonous plants. Acknowledging this necessity and the role of cereals in food security, rice (Oryza sativa L.) was launched as a genetic and genomic model several years ago (Goff et al., 2002; Project, 2005). These efforts facilitated advances in comparative genomics, and demonstrated that characterization of the genic content and landscape of one grass species could be informative and applicable to other related species (Gale and Devos, 1998; Phillips and Freeling, 1998). Rice also turned out to be a useful model to study plant immunity and the existing genomic resources and tools in this species are highly valuable to plant scientists and breeders (Phillips and Freeling, 1998; Chen and Ronald, 2011; Chen et al., 2013). Nevertheless, basic biological and physiological differences between Oryza spp. and temperate grasses can hinder rice’s utility to inform on certain processes, like rust resistance, in cool-season crops (Phillips and Freeling, 1998; Draper et al., 2001; Vogel and Bragg, 2009; Chen et al., 2013). Disease resistance in rice to important cereal pathogens is not always genetically tractable. While rice acts as a non-host to all rust species, the variation in NHR phenotypes across cultivars can be subtle and often influenced by environmental factors; limiting the value of rice in rust research (Ayliffe et al., 2011, 2013).

To tackle some of these challenges, the small wild grass Brachypodium distachyon (Pooideae subfamily), also known as purple false brome, was developed as an experimental model to investigate temperate grass biology (Draper et al., 2001; Vogel and Bragg, 2009; Brkljacic et al., 2011; Mur et al., 2011). B. distachyon diverged from the wheat phylogenetic lineage approximately 35–40 million years ago indicating it is more closely related to Triticeae than rice (Bossolini et al., 2007). As a species, B. distachyon has no agronomic value; however, it possesses biological attributes advantageous for its use as a model system (Draper et al., 2001; Vogel and Bragg, 2009; Mur et al., 2011). Similar to A. thaliana, B. distachyon exhibits a small plant size, compact genome (∼270–300 Mb), short life cycle (2–3 months), genetic tractability, and minimal growth requirements. There are several species within the genus Brachypodium and their taxonomic classification has been recently resolved (Catalán et al., 2012; López-Alvarez et al., 2012). B. distachyon and B. stacei include diploid plants with 5 and 10 pairs of chromosomes, respectively; whereas B. hybridum is an allotetraploid species that resulted from a hybridization event between B. distachyon and B. stacei (López-Alvarez et al., 2012). The different ploidies within the genus offers opportunity to conduct evolutionary, gene inheritance and expression studies in a system that is easier to handle than related crops like wheat and oat. The embracement of Brachypodium as model has resulted in a wealth of genetic, genomic, and experimental assets that set the stage to answer many interesting questions in plant biology and pathology. Some of the established resources include large natural germplasm collections and several families of recombinant inbred lines available to the scientific community (Jenkins et al., 2003; Vogel et al., 2006a, 2009; Vogel and Hill, 2008; Scoles et al., 2009). In addition, there is access to bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) and expressed sequence tag (EST) libraries (Vogel et al., 2006b; Huo et al., 2008), genetic and physical maps (Febrer et al., 2010), simple sequence repeat (SSR) microsatellite markers (Azhaguvel et al., 2009; Vogel et al., 2009; Garvin et al., 2010), a high quality Sanger-based reference genome assembly of B. distachyon inbred line Bd21 and deep sequencing data corresponding to additional genotypes1 (International Brachypodium Initiative, 2010; Gordon et al., 2013). The implementation of efficient Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation methods allowed the creation of two large banks of T-DNA insertion mutants in B. distachyon2,3, which are also a great resource available to the community (Alves et al., 2009; Bragg et al., 2012; Thole et al., 2012).

From the perspective of research in plant immunity, B. distachyon is emerging as a suitable system to investigate plant–microbe interactions (Fitzgerald et al., 2015). In contrast to rice, Brachypodium species can act as a host to Puccinia brachypodii, an adapted pathogen of B. sylvaticum, thus better positioning this system to investigate various aspects of rust compatibility (Barbieri et al., 2011). Initial pathogenicity tests on various ecotypes of B. distachyon showed the potential of the species to investigate the molecular basis of resistance against pathogens like Blumeria graminis, Magnaporthe oryzae, and various rust fungi such as P. hordei, P. triticina, P. striiformis f. sp. tritici and P. striiformis f. sp. hordei (Draper et al., 2001; Routledge et al., 2004; Peraldi et al., 2011). Since these early reports, the number of studies examining the interaction of B. distachyon with pathogenic fungi, some of which affect food and biofuel crops, is growing. B. distachyon has been established as a pathosystem to study important grain diseases such as to Fusarium head blight, caused by Fusarium graminearum (Peraldi et al., 2011), Rhizoctonia root rot in wheat, caused by Rhizoctonia solani (Schneebeli et al., 2014), spot blotch and common root rot caused by Cochliobolus sativus (Zhong et al., 2014), Septoria tritici blotch disease, caused by Zymoseptoria tritici (O’Driscoll et al., 2015), take-all caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis (Sandoya and de Oliveira Buanafina, 2014), Stagonospora nodorum blotch and net blotch of barley caused by Pyrenophora teres (Falter and Voigt, 2014), as well as other grass diseases caused by Sclerotinia homoeocarpa and Ophiosphaerella agrostis (Sandoya and de Oliveira Buanafina, 2014).

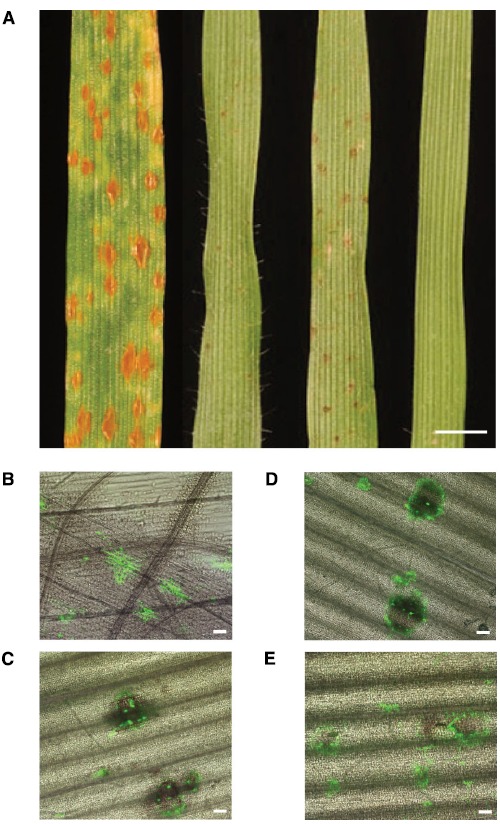

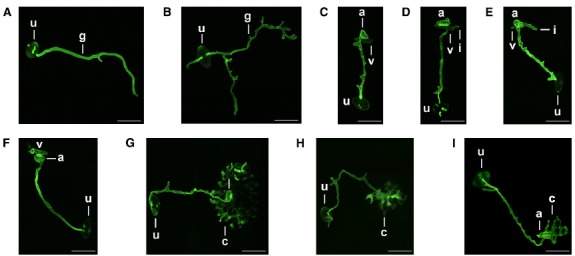

The role of Brachypodium spp. as a non-host to formae speciales of rust fungi, notably P. graminis, P. triticina, and P. striiformis, is now very well-established (Garvin, 2011; Ayliffe et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2013). Most recently, B. distachyon was also recognized as a non-host to P. emaculata, the causal agent of switchgrass rust (Gill et al., 2015). Challenging Brachypodium spp. with non-adapted rust fungi results in symptoms that are remarkably different than typical symptoms in compatible interactions (Figure 1A; Barbieri et al., 2011; Ayliffe et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2013; Gill et al., 2015). The density and appearance of these symptoms varies greatly. Certain Brachypodium-rust interactions result in immunity, whereas others can display symptoms at a macroscopic scale, ranging from small necrotic flecks to spreading necrotic and/or chlorotic lesions that may surround small sporulating pustules, responses that are absent in fully-compatible interactions (Figures 1A–E; Ayliffe et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2013). In cases where macroscopic symptoms are completely absent due to either failure of the fungus to accomplish plant colonization and/or reach sporulation stages, only microscopic examination of inoculated tissue can allow symptom visualization. B. distachyon possesses sufficient chemical, topographical, and thigmotropic signals to induce differentiation of appressoria and in some cases, substomatal vesicles, by most Puccinia species examined; although orientation of the germ tube can be affected as in the case of P. emaculata (Gill et al., 2015). If fungal growth occurs in the mesophyll space, the infection can advance to the formation of haustoria and sporulating pustules (Figure 2; Ayliffe et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2013). Interestingly, the formation of haustoria and pustules was not detected in the P. emaculata–B. distachyon interaction (Gill et al., 2015). However, such observations could be specific to the P. emaculata isolate used in their study. The resistance of B. distachyon to P. graminis f. sp. tritici has been observed as prehaustorial, as most of the infection sites failed to display growth in the plant mesophyll (Figueroa et al., 2013), and post-haustorial, as different races of stem rust fungus can accomplish the formation of colonies that vary in size (Figures 2C–E; Ayliffe et al., 2013). Most importantly for genetic studies, resistance in Brachypodium to rust fungi varies substantially across accessions or inbred lines. This phenotypic variability makes it possible to employ genetic-based approaches to map and clone genes governing stem rust resistance in Brachypodium species. In fact, differential phenotypes of B. distachyon inbred lines Bd3-1 and Bd1-1 in response to P. brachypodii allowed the identification of three distinctive rust resistance quantitative trait loci QTLs (Barbieri et al., 2011, 2012). Assessment of the inheritance of the resistance to P. striiformis f. sp. tritici in two different B. distachyon mapping families from parental lines with contrasting phenotypes, BdTR13k × Bd21 and Bd10TR10h × TEK4, suggested that major differences in NHR are simply inherited (Ayliffe et al., 2013). Similar differential responses to P. graminis f. sp. tritici have been detected in multiple B. distachyon inbred lines and accessions (Ayliffe et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2013), encouraging comparable resistance inheritance studies against this pathogen.

FIGURE 1.

Symptoms induced by P. graminis f. sp. tritici in wheat and B. distachyon. (A) Left to right, macroscopic symptoms of P. graminis f. sp. tritici (CRL 75-36-700-3) in susceptible Triticum aestivum cv. McNair 701, B. distachyon inbred lines Bd1-1, Bd2-3, Bd21 at 12 days after inoculation, scale = 2 mm. (B–E) Microscopic symptoms induced by P. graminis f. sp. tritici and various inbred lines of B. distachyon at 96 h post-inoculation. Inoculations were performed as previously reported (Figueroa et al., 2013). Fungal tissue was stained with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (WGA-FITC; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as previously described (Ayliffe et al., 2013). (B) Susceptible Triticum aestivum cv. McNair 701. (C) Inbred line Bd1-1. (D) Inbred line Bd2-3. (E) Inbred line Bd21. Images were generated by merging bright and fluorescence fields captured using an Olympus IX70 Inverted Fluorescence Microscope, scale = 100 μm.

FIGURE 2.

Differentiation of morphological structures associated with the infection of P. graminis f. sp. tritici on B. distachyon. P. graminis f. sp. tritici (CRL 75-36-700-3) was used to inoculate various B. distachyon inbred lines following procedures previously reported (Figueroa et al., 2013). Fungal tissue was stained WGA-FITC as previously described (Ayliffe et al., 2013). (A,B) Germination of urediniospores (u) on the surface of leaves of B. distachyon inbred line Bd1-1, micrographs illustrate the different morphological features of germ tubes as they elongate to locate a stoma. (C–E) Differentiation of an appressorium (a) and substomatal vesicle (v) in B. distachyon inbred lines Bd1-1, Bd2-3, Bd21, respectively, at 24 hpi (10 h of light exposure). Notice differences in the growth of primary infection hyphae (i) as it emerges from the substomatal vesicle. (F) Example of an infection site in B. distachyon inbred line Bd1-1 that failed to continue growth after forming the appressorium and substomatal vesicle. Image was capture at 96 hpi. (G–I) Presence of rust fungal colonies in B. distachyon inbred lines Bd1-1, Bd2-3, Bd21, respectively, at 96 hpi. Images were captured using epifluorescence in a Nikon A1 Spectral Confocal Microscope, scale = 50 μm.

Our understanding of the genomic architecture controlling NHR in B. distachyon is in its infancy. Microscopic analyses and transcriptional profiling have started to shed light into the mechanisms that could mediate resistance in B. distachyon against non-adapted rust pathogens. Accumulation of callose and papillae formation has been observed at infection sites during penetration (substomatal vesicles) in interactions with P. graminis ff. spp. tritici, lolii, and phleipratensis, P. striiformis f. sp. tritici, and P. triticina (Ayliffe et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2013). Interestingly, comparisons of callose deposition at infection sites where the growth of rust fungi was arrested in both host and non-host scenarios, suggests that both types of mechanisms of resistance share common responses and supports the role of PTI in NHR (Ayliffe et al., 2013). Quantification of transcript abundance when three different B. distachyon inbred lines were challenged with P. emaculata suggest a mixture of responses linked to jasmonic acid, ethylene, and salicylic acid signaling pathways, as well as induction of HRs (Gill et al., 2015). In contrast, evaluation of salicylic acid levels indicated no change in response to P. graminis f. sp. tritici (Ayliffe et al., 2013). While cell death and dark pigmentation in the rust-infected tissue of various Brachypodium accessions and lines is commonly observed (Figures 1C–E; Ayliffe et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2013), microscopic analyses indicated that such necrotic responses are not typically associated with autofluorescence, suggesting that hypersensitive cell death is not playing a role in NHR (Ayliffe et al., 2013).

The relative contributions of ETI and PTI to NHR is a long-standing question. It is thought that evolutionary distance between host and non-host plays a major role in determining the relative importance of ETI and PTI processes in these plant–microbe interactions, with ETI favored in non-hosts that are closely related to the natural host (Schulze-Lefert and Panstruga, 2011; Bettgenhaeuser et al., 2014). The phenotypic outcome of Brachypodium-rust interactions appear to be highly influenced by the genotype of both plant and fungus, which suggests a relatively strong ETI component to these NHR interactions (Ayliffe et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2013; Bettgenhaeuser et al., 2014; Gill et al., 2015). Members of P. graminis which are pathogens of plants in the tribe Aveneae and Poeae (ff. spp. avenae, lolii, phalaridi, phleipratensis) are more likely to form sporulating pustules on Brachypodium accessions than P. graminis f. sp. tritici (Ayliffe et al., 2013; Figueroa et al., 2013), which supports the view that such interactions resemble more host resistance responses (Ayliffe et al., 2013; Bettgenhaeuser et al., 2014). Future studies are required to carefully evaluate whether ETI is playing a role in the resistance of B. distachyon against non-adapted rust pathogens. The mode-of-action of R genes and other broad-spectrum resistance genes is often poorly understood, and therefore, the efficacy of their use in breeding programs is likely undermined. Elucidation of the mechanisms of action of these genes is an area of investigation that could be strengthened by basic research in model plants like B. distachyon.

The B. distachyon T-DNA insertion mutant resources provide an excellent platform to enable reverse genetics and functional genomic approaches to identify major components of NHR against rust fungi. In addition, the various levels of disease resistance in Brachypodium against rust isolates can be exploited to conduct genetic-based approaches to identify, map and clone genes that govern NHR. Recent genomic advances and catalogs of high confidence predicted effectors in North American and Australian stem rust isolates (Duplessis et al., 2011; Upadhyaya et al., 2015) have positioned P. graminis f. sp. tritici as an ideal organism to investigate the role of ETI during NHR. In combination with the resources available for B. distachyon, P. graminis f. sp. tritici makes a powerful system to investigate the strategies by which obligate biotrophs can be able to reproduce in the face of less suited “host” environments.

Additionally, the Brachypodium NHR system could be regarded as a potential source of genetic disease resistance for cereals. The effectiveness of B. distachyon derived-genes in transgenic cereals as a strategy for crop protection has not been evaluated yet; however, the high genome collinearity and synteny among the species (International Brachypodium Initiative, 2010) suggests that such genes have high probability of being effective in cereal crops. On the other hand, advances in unraveling the genomic structure and organization of Hordeum vulgare (International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium et al., 2012) and Triticum aestivum (Mayer et al., 2014), and the seed transcriptome assembly of Avena sativa (Gutierrez-Gonzalez et al., 2013) will enable comparisons with B. distachyon, which could be useful to support engineering of disease resistance programs via genome editing techniques.

In addition to its utility in studying NHR, it may be possible to utilize B. distachyon for experimentation essentially as a host if sufficiently compatible accession-pathotype combinations can be found. Natural infections of P. striiformis resulting in large uredinia have been observed on several accessions grown in nurseries in the Pacific Northwest, where pathotype variation is very high (E. Elmore, Pers. Comm.). Further development of this pathosystem by identifying the most compatible pathotype-accession combination, or possibly generating new lines by crossing the most susceptible accessions, would enable researchers to take advantage of B. distachyon’s amenability to transformation. High density marker systems for cereals are enabling candidate R genes to be identified relatively easily, but verification of the candidates are still lacking because transformation systems for wheat and barley are very inefficient. A compatible B. distachyon stripe rust system could be used to test candidate stripe rust genes or other components of resistance for function in stably transformed plants. Resistance signaling pathways could be examined by introducing heterologous R genes with, or without, other required donor species components or by using B. distachyon mutants. Novel approaches to engineering resistance could be tested in B. distachyon transgenics. An example would be RNAi constructs that appear to silence essential rust fungus genes and confer resistance but have only been tested by transient assays to date (Panwar et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2014). Fungal genes, like those encoding putative effectors, could be stably expressed in B. distachyon to examine their effects on host physiology to provide insight into their function.

Conclusions and Remarks

Current trends in food and bioenergy production systems compel the development of transformative approaches to combat plant disease in a sustainable and environmentally safe manner. Rust fungi are among the most important pathogens of grasses and cereals. Understanding the biology of these organisms, especially their mechanisms of virulence and host specificity, is essential to understand emergence of new pathogens or races. Exploring non-host and host pathogen interactions within a single rust species offers unique opportunities to also investigate how new pathogens emerge. Such fundamental knowledge can aid in planning and designing effective and long lasting crop protection strategies. The prospect of exploiting NHR as a natural durable approach to decrease crop yield losses due to biotic stress is well-supported. Defining the molecular and genetic mechanisms conferring NHR is not particularly straightforward given its presumed polygenic nature. However, the amenability of Brachypodium-rust fungi as a model pathosystem may accelerate the discovery of molecular and genetic mechanisms underpinning NHR. One avenue to uncover the genetic factors that control disease outcome is the screening of mutagenized Brachypodium populations to identify mutants that show susceptibility/compatibility to rust fungi. Combining genetic and genomic tools in both crops and model systems can result in foundational knowledge to support translational plant research. Model-to-crop studies can strengthen plant genetic engineering programs and their potential benefits to agriculture outweigh the time and scale of investments that such studies require. Genome editing techniques and transgenic technologies have quickly emerged as powerful research tools that can enhance traditional plant breeding techniques (Belhaj et al., 2013; Dangl et al., 2013). In spite of regulatory debates and controversial views, these approaches offer great potential to reduce crop yield losses and enable engineering of durable and sustainable plant disease resistance as exemplified by the commercial use of the genetically engineered multiviral resistant squash (Tricoll et al., 1995) and ringspot virus resistant papaya (Lius et al., 1997; Ferreira et al., 2002). Thus, it is worthwhile to invest efforts and research funding to build experimental systems that are meaningful to address immediate societal needs.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support from start-up funds provided by the University of Minnesota. We thank Grant Barthel at the University Imaging Center (http://uic.umn.edu/), and Matthew Martin at the Department of Plant Pathology for their assistance during collection of photographs, David Garvin for sharing seed stocks of B. distachyon inbred lines and the Cereal Disease Laboratory, USDA-ARS, St. Paul, MN for providing the isolate of P. graminis f. sp. tritici (CRL 75-36-700-3). We also thank the Stakman-Borlaug Center (SBC) for Sustainable Plant Health at the University of Minnesota for their supportive role to continue this research. The SBC brings together diverse multidisciplinary teams to tackle problems with both national and international relevance and is especially interested in innovative approaches to minimize the impact of rust pathogens in wheat, oat, and other crops which comprise economically and socially significant agricultural threats.

Footnotes

References

- Al-Kherb S. M., Roelfs A., Groth J. (1987). Diversity for virulence in a sexually reproducing population of Puccinia coronata. Can. J. Bot. 65, 994–998. 10.1139/b87-137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alves S. C., Worland B., Thole V., Snape J. W., Bevan M. W., Vain P. (2009). A protocol for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Brachypodium distachyon community standard line Bd21. Nat. Protoc. 4, 638–649. 10.1038/nprot.2009.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C. L., Bremer K., Friis E. M. (2005). Dating phylogenetically basal eudicots using rbcL sequences and multiple fossil reference points. Am. J. Bot. 92, 1737–1748. 10.3732/ajb.92.10.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anikster Y. (1984). “The formae speciales,” in The Cereals Rusts, Vol 1, eds Bushnell W. R., Roelfs A. P. (Orlando, FL: Academic Press, Inc; ), 124–137. [Google Scholar]

- Ayliffe M., Singh D., Park R., Moscou M. J., Pryor T. (2013). The infection of Brachypodium distachyon with selected grass rust pathogens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 26, 946–957. 10.1094/MPMI-01-13-0017-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayliffe M. A., Jin Y., Kang Z., Persson M., Steffenson B., Wang S., et al. (2011). Determining the basis of nonhost resistance in rice to cereal rusts. Euphytica 179, 33–40. 10.1007/s10681-010-0280-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azhaguvel P., Li W., Rudd J. C., Gill B. S., Michels G., Weng Y. (2009). Aphid feeding response and microsatellite-based genetic diversity among diploid Brachypodium distachyon (L.) Beauv accessions. Plant Gen. Res. 7, 72–79. 10.1017/S1479262108994235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri M., Marcel T. C., Niks R. E. (2011). Host status of false brome grass to the leaf rust fungus Puccinia brachypodii and the stripe rust fungus P. striiformis. Plant Dis. 95, 1339–1345. 10.1094/PDIS-11-10-0825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri M., Marcel T. C., Niks R. E., Francia E., Pasquariello M., Mazzamurro V., et al. (2012). QTLs for resistance to the false brome rust Puccinia brachypodii in the model grass Brachypodium distachyon L. Genome 55, 152–163. 10.1139/g2012-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belhaj K., Chaparro-Garcia A., Kamoun S., Nekrasov V. (2013). Plant genome editing made easy: targeted mutagenesis in model and crop plants using the CRISPR/Cas system. Plant Methods 9, 39. 10.1186/1746-4811-9-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettgenhaeuser J., Gilbert B., Ayliffe M., Moscou M. J. (2014). Nonhost resistance to rust pathogens–a continuation of continua. Front. Plant Sci. 5:664. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley J., Bradford K., Hilhorst H., Nonogaki H. (2012). Seeds: Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy. New York: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Biffen R. H. (1907). Studies in the inheritance of disease-resistance. J. Agric. Sci. 2, 109–128. 10.1017/S0021859600001234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bossolini E., Wicker T., Knobel P. A., Keller B. (2007). Comparison of orthologous loci from small grass genomes Brachypodium and rice: implications for wheat genomics and grass genome annotation. Plant J. 49, 704–717. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02991.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg J. N., Wu J., Gordon S. P., Guttman M. E., Thilmony R., Lazo G. R., et al. (2012). Generation and characterization of the western regional research center Brachypodium T-DNA insertional mutant collection. PLoS ONE 7:e41916. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A., Gow N. A. (2012). “Tropic orientation responses of pathogenic fungi,” in Morphogenesis and Pathogenicity in Fungi, eds Pérez-Martín J., Di Pietro A. (Heidelberg: Springer; ), 21–41. 10.1007/978-3-642-22916-9_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brkljacic J., Grotewold E., Scholl R., Mockler T., Garvin D. F., Vain P., et al. (2011). Brachypodium as a model for the grasses: today and the future. Plant Physiol. 157, 3–13. 10.1104/pp.111.179531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalán P., Müller J., Hasterok R., Jenkins G., Mur L. A., Langdon T., et al. (2012). Evolution and taxonomic split of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Ann. Bot. 109, 385–405. 10.1093/aob/mcr294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzariti A.-M., Dodds P. N., Ellis J. G. (2007). Avirulence proteins from haustoria-forming pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 269, 181–188. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00684.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzariti A. M., Dodds P. N., Lawrence G. J., Ayliffe M. A., Ellis J. G. (2006). Haustorially expressed secreted proteins from flax rust are highly enriched for avirulence elicitors. Plant Cell 18, 243–256. 10.1105/tpc.105.035980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman G. P. (1996). The Biology of Grasses. Salisbury: CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- Chaw S.-M., Chang C.-C., Chen H.-L., Li W.-H. (2004). Dating the monocot–dicot divergence and the origin of core eudicots using whole chloroplast genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 58, 424–441. 10.1007/s00239-003-2564-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawade A., Sikora P., Bräutigam M., Larsson M., Vivekanand V., Nakash M. A., et al. (2010). Development and characterization of an oat TILLING-population and identification of mutations in lignin and β-glucan biosynthesis genes. BMC Plant Biol. 10:86. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., He H., Zhou F., Yu H., Deng X. W. (2013). Development of genomics-based genotyping platforms and their applications in rice breeding. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 247–254. 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Ronald P. C. (2011). Innate immunity in rice. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 451–459. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins G. B. (1971). The Rust Fungi of Cereals, Grasses, and Bamboos. New York, NY: Spinger-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Dangl J. L., Horvath D. M., Staskawicz B. J. (2013). Pivoting the plant immune system from dissection to deployment. Science 341, 746–751. 10.1126/science.1236011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl J. L., Jones J. D. (2001). Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411, 826–833. 10.1038/35081161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies T. J., Barraclough T. G., Chase M. W., Soltis P. S., Soltis D. E., Savolainen V. (2004). Darwin’s abominable mystery: insights from a supertree of the angiosperms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 1904–1909. 10.1073/pnas.0308127100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R. H., Perkins D. D. (2002). Neurospora: a model of model microbes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 397–403. 10.1038/nrg797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P. N., Rathjen J. P. (2010). Plant immunity: towards an integrated view of plant–pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 539–548. 10.1038/nrg2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douchkov D., Lueck S., Johrde A., Nowara D., Himmelbach A., Rajaraman J., et al. (2014). Discovery of genes affecting resistance of barley to adapted and non-adapted powdery mildew fungi. Genome Biol. 15, 518. 10.1186/s13059-014-0518-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper J., Mur L. A. J., Jenkins G., Ghosh-Biswas G. C., Bablak P., Hasterok R., et al. (2001). Brachypodium distachyon. A new model system for functional genomics in grasses. Plant Physiol. 127, 1539–1555. 10.1104/pp.010196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplessis S., Cuomo C. A., Lin Y. C., Aerts A., Tisserant E., Veneault-Fourrey C., et al. (2011). Obligate biotrophy features unraveled by the genomic analysis of rust fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9166–9171. 10.1073/pnas.1019315108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck P., Samborski D., Anderson R. (1966). Inheritance of adult-plant leaf rust resistance derived from the common wheat varieties Exchange and Frontana. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 8, 665–671. 10.1139/g66-082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J. (2006). Insights into nonhost disease resistance: can they assist disease control in agriculture? Plant Cell 18, 523–528. 10.1105/tpc.105.040584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J. G., Lagudah E. S., Spielmeyer W., Dodds P. N. (2014). The past, present and future of breeding rust resistant wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 5:641. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falter C., Voigt C. A. (2014). Comparative cellular analysis of pathogenic fungi with a disease incidence in Brachypodium distachyon and Miscanthus × giganteus. Bioenergy Res. 7, 958–973. 10.1007/s12155-014-9439-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Febrer M., Goicoechea J. L., Wright J., Mckenzie N., Song X., Lin J., et al. (2010). An integrated physical, genetic and cytogenetic map of Brachypodium distachyon, a model system for grass research. PLoS ONE 5:e13461. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira S., Pitz K., Manshardt R., Zee F., Fitch M., Gonsalves D. (2002). Virus coat protein transgenic papaya provides practical control of papaya ringspot virus in Hawaii. Plant Dis. 86, 101–105. 10.1094/PDIS.2002.86.2.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa M., Alderman S., Garvin D. F., Pfender W. F. (2013). Infection of Brachypodium distachyon by formae speciales of Puccinia graminis: early infection events and host-pathogen incompatibility. PLoS ONE 8:e56857. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald T. L., Powell J. J., Schneebeli K., Hsia M. M., Gardiner D. M., Bragg J. N., et al. (2015). Brachypodium as an emerging model for cereal–pathogen interactions. Ann. Bot. 115, 717–731. 10.1093/aob/mcv010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H. (1971). Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 9, 275–296. 10.1146/annurev.py.09.090171.001423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z. Q., Dong X. (2013). Systemic acquired resistance: turning local infection into global defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 839–863. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale M., Devos K. (1998). Plant comparative genetics after 10 years. Science 282, 656–659. 10.1126/science.282.5389.656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnica D. P., Nemri A., Upadhyaya N. M., Rathjen J. P., Dodds P. N. (2014). The ins and outs of rust haustoria. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004329. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin D. F. (2011). “Investigating rust resistance with the model grass Brachypodium,” in Proceedings of the 2011 Borlaug Global Rust Initiative Technical Workshop, June 13–19, ed. McIntosh R. (St. Paul, MN: ), 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin D. F., Mckenzie N., Vogel J. P., Mockler T. C., Blankenheim Z. J., Wright J., et al. (2010). An SSR-based genetic linkage map of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Genome 53, 1–13. 10.1139/G09-079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill U. S., Uppalapati S. R., Nakashima J., Mysore K. S. (2015). Characterization of Brachypodium distachyon as a nonhost model against switchgrass rust pathogen Puccinia emaculata. BMC Plant Biol. 15:113. 10.1186/s12870-015-0502-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff S. A., Ricke D., Lan T.-H., Presting G., Wang R., Dunn M., et al. (2002). A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science 296, 92–100. 10.1126/science.1068275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S., Priest H., Des Marais D., Schackwitz W., Figueroa M., Martin J., et al. (2013). Genome diversity in Brachypodium distachyon: deep sequencing of highly diverse inbred lines Plant J. 79, 361–374. 10.1111/tpj.12569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L., Kenyon C. (2000). Genetic pathways that regulate ageing in model organisms. Nature 408, 255–262. 10.1038/35041700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Gonzalez J. J., Tu Z. J., Garvin D. F. (2013). Analysis and annotation of the hexaploid oat seed transcriptome. BMC Genomics 14:471. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder D. (1984). “Developmental ultrastructure of hyphae and spores,” in The Cereal Rusts, Vol 1. eds Bushnell W. R., Roelfs A. P. (Orlando, FL: Academic Press, Inc; ), 333–373. [Google Scholar]

- Harder D. E., Chong J. (1984). “Structure and Physiology of Haustoria,” in The Cereal Rusts, Vol 1, Bushnell W. R., Roelfs A. P. (Orlando, FL: Academic Press, Inc.), 416–460. 10.1016/b978-0-12-148401-9.50020-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heath M. C. (1981). A generalized concept of host-parasite specificity. Phytopathology 71, 1121–1123. 10.1094/Phyto-71-1121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heath M. C. (1997). Signalling between pathogenic rust fungi and resistant or susceptible host plants. Ann. Bot. 80, 713–720. 10.1006/anbo.1997.0507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heath M. C. (2000). Nonhost resistance and nonspecific plant defenses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3, 315–319. 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00087-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch H. C., Staples R. C., Whitehead B., Comeau J., Wolf E. D. (1987). Signaling for growth orientation and cell differentiation by surface topography in Uromyces. Science 235, 1659–1662. 10.1126/science.235.4796.1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogenhout S. A., Van Der Hoorn R. A., Terauchi R., Kamoun S. (2009). Emerging concepts in effector biology of plant-associated organisms. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 115–122. 10.1094/MPMI-22-2-0115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huitema E., Vleeshouwers V. G., Francis D. M., Kamoun S. (2003). Active defence responses associated with non-host resistance of Arabidopsis thaliana to the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Mol. Plant Pathol 4, 487–500. 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo N., Lazo G. R., Vogel J. P., You F. M., Ma Y., Hayden D. M., et al. (2008). The nuclear genome of Brachypodium distachyon: analysis of BAC end sequences. Funct. Integr. Genomics 8, 135–147. 10.1007/s10142-007-0062-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium. Mayer K. F., Waugh R., Brown J. W., Schulman A., Langridge P, et al. (2012). A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature 491, 711–716. 10.1038/nature11543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Brachypodium Initiative. (2010). Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature 463, 763–768. 10.1038/nature08747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins G., Hasterok R., Draper J. (2003). “Building the molecular cytogenetic infrastructure of a new model grass,” in Application of Novel Cytogenetic and Molecular Techniques in Genetics and Breeding of the Grasses, eds Zwierzykowski Z., Surma M., Kachlicki P. (Poznan: Polish Academy of Sciences; ), 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Szabo L. J., Carson M. (2010). Century-old mystery of Puccinia striiformis life history solved with the identification of Berberis as an alternate host. Phytopathology 100, 432–435. 10.1094/PHYTO-100-5-0432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. D., Dangl J. L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329. 10.1038/nature05286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib M., Lafitte C., Esquerré-Tugayé M. T., Bottin A., Rickauer M. (2004). The CBEL elicitor of Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotianae activates defence in Arabidopsis thaliana via three different signalling pathways. New Phytol. 162, 501–510. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01043.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koeck M., Hardham A. R., Dodds P. N. (2011). The role of effectors of biotrophic and hemibiotrophic fungi in infection. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 1849–1857. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01665.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krattinger S. G., Lagudah E. S., Spielmeyer W., Singh R. P., Huerta-Espino J., Mcfadden H., et al. (2009). A putative ABC transporter confers durable resistance to multiple fungal pathogens in wheat. Science 323, 1360–1363. 10.1126/science.1166453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence G. J., Dodds P. N., Ellis J. G. (2007). Rust of flax and linseed caused by Melampsora lini. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 349–364. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. A., Kim S. Y., Oh S. K., Yeom S. I., Kim S. B., Kim M. S., et al. (2014). Multiple recognition of RXLR effectors is associated with nonhost resistance of pepper against Phytophthora infestans. New Phytol. 203, 926–938. 10.1111/nph.12861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K., Martinelli J. (2005). Virulence of oat crown rust in Brazil and Uruguay. Plant Dis. 89, 802–808. 10.1094/PD-89-0802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K. J., Szabo L. J. (2005). Pathogen profile. Stem rust of small grains and grasses caused by Puccinia graminis. Mol. Plant Pathol. 6, 489–489. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipka U., Fuchs R., Kuhns C., Petutschnig E., Lipka V. (2010). Live and let die–Arabidopsis nonhost resistance to powdery mildews. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 89, 194–199. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lius S., Manshardt R. M., Fitch M. M., Slightom J. L., Sanford J. C., Gonsalves D. (1997). Pathogen-derived resistance provides papaya with effective protection against papaya ringspot virus. Mol. Breed. 3, 161–168. 10.1023/A:1009614508659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López-Alvarez D., López-Herranz M. L., Betekhtin A., Catalán P. (2012). A DNA barcoding method to discriminate between the model plant Brachypodium distachyon and its close relatives B. stacei and B. hybridum (Poaceae). PloS ONE 7:e51058. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier W., Begerow D., Weiß M., Oberwinkler F. (2003). Phylogeny of the rust fungi: an approach using nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Can. J. Bot. 81, 12–23. 10.1139/b02-113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer K. F., Rogers J., Doležel J., Pozniak C., Eversole K., Feuillet C., et al. (2014). A chromosome-based draft sequence of the hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) genome. Science 345, 1251788. 10.1126/science.1251788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklos G. L. G., Rubin G. M. (1996). The role of the genome project in determining gene function: insights from model organisms. Cell 86, 521–529. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80126-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan J., Zipfel C. (2012). Plant pattern recognition receptor complexes at the plasma membrane. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 349–357. 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mur L. A., Allainguillaume J., Catalan P., Hasterok R., Jenkins G., Lesniewska K., et al. (2011). Exploiting the Brachypodium tool box in cereal and grass research. New Phytol. 191, 334–347. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysore K. S., Ryu C. M. (2004). Nonhost resistance: how much do we know? Trends Plant Sci. 9, 97–104. 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirmala J., Drader T., Chen X., Steffenson B., Kleinhofs A. (2010). Stem rust spores elicit rapid RPG1 phosphorylation. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 1635–1642. 10.1094/MPMI-06-10-0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirmala J., Drader T., Lawrence P. K., Yin C., Hulbert S., Steber C. M., et al. (2011). Concerted action of two avirulent spore effectors activates Reaction to Puccinia graminis 1 (Rpg1)-mediated cereal stem rust resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 14676–14681. 10.1073/pnas.1111771108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll A., Doohan F., Mullins E. (2015). Exploring the utility of Brachypodium distachyon as a model pathosystem for the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. BMC Res. Notes 8:132. 10.1186/s13104-015-1097-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oerke E.-C. (2006). Crop losses to pests. J. Agric. Sci. 144, 31–43. 10.1017/S0021859605005708 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panstruga R., Dodds P. N. (2009). Terrific protein traffic: the mystery of effector protein delivery by filamentous plant pathogens. Science 324, 748–750. 10.1126/science.1171652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panwar V., Mccallum B., Bakkeren G. (2013). Endogenous silencing of Puccinia triticina pathogenicity genes through in planta-expressed sequences leads to the suppression of rust diseases on wheat. Plant J. 73, 521–532. 10.1111/tpj.12047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park R. (2008). Breeding cereals for rust resistance in Australia. Plant Pathol. 57, 591–602. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2008.01836.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi E. (2010). Armed and dangerous. Science 327, 804–805. 10.1126/science.327.5967.804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peraldi A., Beccari G., Steed A., Nicholson P. (2011). Brachypodium distachyon: a new pathosystem to study Fusarium head blight and other Fusarium diseases of wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 100–114. 10.1186/1471-2229-11-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R. L., Freeling M. (1998). Plant genomics and our food supply: an introduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1969–1970. 10.1073/pnas.95.5.1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquerez S. J. M., Harvey S. E., Beynon J. L., Ntoukakis V. (2014). Improving crop disease resistance: lessons from research on Arabidopsis and tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 5:671. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp J., Hantos K. (2011). The impact of crop protection on agricultural production. Stud. Agric. Econ. 113, 47–66. 10.7896/j.1003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius Z. A., Singh R. P., Wagoire W. W., Payne T. S. (2000). Detection of virulence to wheat stem rust resistance gene Sr31 in Puccinia graminis. f. sp. tritici in Uganda. Plant Dis. 84, 203 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.2.203B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project I. R. G. S. (2005). The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature 436, 793–800. 10.1038/nature03895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D. K., Mueller N. D., West P. C., Foley J. A. (2013). Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLoS ONE 8:e66428. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Replansky T., Koufopanou V., Greig D., Bell G. (2008). Saccharomyces sensu stricto as a model system for evolution and ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 494–501. 10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk J. M., Selter L. L., Chauhan H., Krattinger S. G., Kumlehn J., Hensel G., et al. (2013). The wheat Lr34 gene provides resistance against multiple fungal pathogens in barley. Plant Biotech. J. 11, 847–854. 10.1111/pbi.12077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfs A. P., Singh R. P., Saari E. E. (1992). Rust Diseases of Wheat: Concepts and Methods of Disease Management. Mexico, DF: CIMMYT. [Google Scholar]

- Routledge A. P., Shelley G., Smith J. V., Talbot N. J., Draper J., Mur L. A. (2004). Magnaporthe grisea interactions with the model grass Brachypodium distachyon closely resemble those with rice (Oryza sativa). Mol. Plant Pathol. 5, 253–265. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoya G. V., de Oliveira Buanafina M. M. (2014). Differential responses of Brachypodium distachyon genotypes to insect and fungal pathogens. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 85, 53–64. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2014.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneebeli K., Mathesius U., Watt M. (2014). Brachypodium distachyon is a pathosystem model for the study of the wheat disease rhizoctonia root rot. Plant Pathol. 64, 91–100. 10.1111/ppa.12227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Lefert P., Panstruga R. (2011). A molecular evolutionary concept connecting nonhost resistance, pathogen host range, and pathogen speciation. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 117–125. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann G. L. (1991). Plant Diseases: Their Biology and Social Impact. St. Paul, MN: APS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scoles G., Filiz E., Ozdemir B., Budak F., Vogel J., Tuna M., et al. (2009). Molecular, morphological, and cytological analysis of diverse Brachypodium distachyon inbred lines. Genome 52, 876–890. 10.1139/G09-062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla K., Srivastava S. (2014). Evaluation of finger millet incorporated noodles for nutritive value and glycemic index. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51, 527–534. 10.1007/s13197-011-0530-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. (1993). Genetic association of gene Bdv1 for tolerance to barley yellow dwarf virus with genes Lr 34 and Yr18 for adult plant resistance to rusts in bread wheat. Plant Dis. 77, 1103–1106. 10.1094/PD-77-1103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. P., Hodson D. P., Jin Y., Huerta-Espino J., Kinyua M., Wanyera R., et al. (2006). Current status, likely migration and strategies to mitigate the threat to wheat production from race Ug99 (TTKS) of stem rust pathogen. CAB Rev. 1, 54 10.1079/PAVSNNR20061054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C. (2007). Biofuels. Curr. Biol. 17, R115–R119. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples R. C., Macko V. (2004). “Germination of urediniospores and differentiation of infection structures,” in The Cereal Rusts, Vol. 1, eds Bushell W. R., Roelfs A. P. (Academic Press, Inc.), 250–282. [Google Scholar]

- Stotz H. U., Mitrousia G. K., De Wit P. J., Fitt B. D. (2014). Effector-triggered defence against apoplastic fungal pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 491–500. 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thole V., Peraldi A., Worland B., Nicholson P., Doonan J. H., Vain P. (2012). T-DNA mutagenesis in Brachypodium distachyon. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 567–576. 10.1093/jxb/err333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D., Balzer C., Hill J., Befort B. L. (2011). Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20260–20264. 10.1073/pnas.1116437108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricoll D. M., Carney K. J., Russell P. F., Mcmaster J. R., Groff D. W., Hadden K. C., et al. (1995). Field evaluation of transgenic squash containing single or multiple virus coat protein gene constructs for resistance to cucumber mosaic virus, watermelon mosaic virus 2, and zucchini yellow mosaic virus. Nat. Biotechnol. 13, 1458–1465. 10.1038/nbt1295-1458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya N. M., Garnica D. P., Karaoglu H., Sperschneider J., Nemri A., Xu B., et al. (2015). Comparative genomics of Australian isolates of the wheat stem rust pathogen Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici reveals extensive polymorphism in candidate effector genes. Front. Plant Sci. 5:759. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. (2015). International Data Base. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/worldpop/table_population.php

- Vogel J., Bragg J. (2009). “Brachypodium distachyon, a new model for the Triticeae,” in Genetics and Genomics of the Triticeae, eds Feuillet C., Muehlbauer G. J. (New York: Springer; ), 427–449. 10.1007/978-0-387-77489-3_16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J., Hill T. (2008). High-efficiency Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Brachypodium distachyon inbred line Bd21-3. Plant Cell Rep. 27, 471–478. 10.1007/s00299-007-0472-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J. P., Garvin D. F., Leong O. M., Hayden D. M. (2006a). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and inbred line development in the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 84, 199–211. 10.1007/s11240-005-9023-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J. P., Gu Y. Q., Twigg P., Lazo G. R., Laudencia-Chingcuanco D., Hayden D. M., et al. (2006b). EST sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Theor. Appl. Genet. 113, 186–195. 10.1007/s00122-006-0285-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J. P., Tuna M., Budak H., Huo N., Gu Y. Q., Steinwand M. A. (2009). Development of SSR markers and analysis of diversity in Turkish populations of Brachypodium distachyon. BMC Plant Biol. 9:88. 10.1186/1471-2229-9-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl I., Anikster Y., Manisterski J., Segal A. (1984). “Evolution at the center of origin,” in The Cereal Rusts, Vol. 1, Origins, Specificity, Structure, and Physiology, eds Bushnell W. R., Roelfs A. P. (Orlando: Academic Press, Inc; ), 39–77. [Google Scholar]

- Woodham-Smith C. (1991). The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845–1849. London: Penguin books. [Google Scholar]

- Yin C., Park J.-J., Gang D. R., Hulbert S. H. (2014). Characterization of a tryptophan 2-monooxygenase gene from Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici involved in auxin biosynthesis and rust pathogenicity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27, 227–235. 10.1094/MPMI-09-13-0289-FI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Ali S., Leng Y., Wang R., Garvin D. F. (2014). Brachypodium distachyon–Cochliobolus sativus pathosystem is a new model for studying plant–fungal interactions in cereal crops. Phytopathology 105, 482–489. 10.1094/PHYTO-08-14-0214-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]